By Brendan P

O'Reilly

Speaking Freely is an Asia Times Online feature that

allows guest writers to have their say. Please click here

if you are interested in contributing. "At present, we

are stealing the future, selling it in the present, and calling it GDP."

-

Paul Hawken There is a dangerous lie that permeates

the media, government and general discourse of nearly every single nation on

Earth.

That lie is the Development Deception. This myth is based on

three concepts. First is the distinction between the developed nations (North America, Western Europe, Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, and

Japan), and the Developing Nations (everywhere else).

The second idea is

that "developing" countries can become "developed" through improved education,

stable governance, and opening their markets to trade and investment. The third

leg of this Deception is that such a transformation is not only possible, but

also desirable.

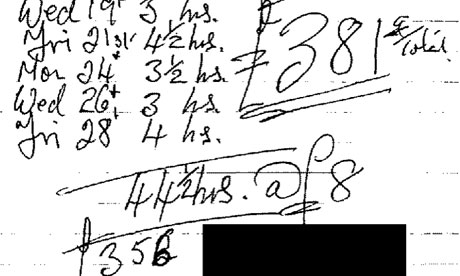

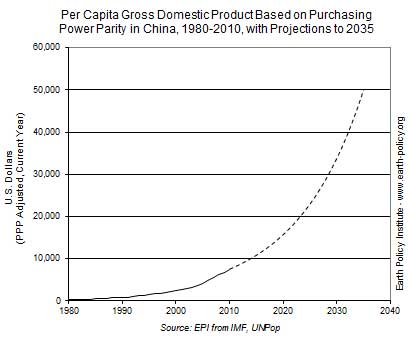

The metric used to distinguish "developed" nations from

"developing" nations is gross domestic product (GDP) per capita. Poor nations

aspire to reach a certain economic level to become so-called "developed

nations". The Myth of Development has four fundamental inter-related flaws. The

first one is the problem of the Gray Area.

The gap between "developed"

and "developing" countries is presented as a simple black-and-white dichotomy. I

often hear from my Chinese students say, "China is a developing country. America

is a developed country. We want to become a developed country."

Fair

enough. But which country has high-speed trains? Which country has a higher

unemployment rate? How can the government of a "developed" country owe trillions

of dollars to a "developing" country?

Obviously many nations in Asia and

Africa, and Latin America have very serious structural problems, which could be

alleviated through stable government and educational reform. Very poor countries

should aspire to create social and economic institutions that allow their people

to live with dignity. Nevertheless the rise of new economic powers such as

Brazil, India, and (especially) China, coupled with the massive financial

difficulties faced by Europe, Japan, and the United States, call into question

the utility of the developed/developing dichotomy.

The second problem

with the Myth of Development is philosophical. The very term "development"

implies a steady linear progression from poverty and ignorance to wealth,

literacy, and general happiness. This viewpoint is Western in origin, and alien

to many of the world’s cultures.

The idea of the inexorable march of

progress has roots in the Judeo-Christian worldview of time (God creates the

world, the world exists, the world ends), and has been largely co-opted by

modern science. We are told to believe that progress is inevitable, that the

quality of life for each new generation will be better than the life of their

parents. Never mind the fact that humanity has created weapons that empower a

handful of political leaders to destroy civilization itself.

Never mind

obesity is now challenging starvation as a cause of premature death. Of course,

the advances made in the last century in curing diseases, increasing literacy

rates, and fighting hunger must be lauded. However, to blindly value "progress"

above all else threatens our very survival as a species.

The third

problem with the Development Deception stems from definitions. As mentioned

previously, GDP per capita is the standard the yardstick for measuring

development. This assessment ignores serious social difficulties faced by the

so-called developed nations.

For example, a third of the adult

population of the United States of America, the archetype "developed" nation,

suffer from obesity, with another third classified as overweight. The United

States of America also has the dubious distinction of having the highest

incarceration rate of any nation on Earth.

Meanwhile Japan, the paragon

of "development" in Asia, has one of the lowest fertility rates in the world,

leading to a rapidly aging population. This trend, unless dramatically reversed,

will exacerbate Japan’s social, economic, and political crisis, as more retirees

put enormous strain on the working population. Japan’s population is set to

shrink by roughly thirty million over the next four decades (Citation

here). Are

these worthy goals for the so-called "developing" nations to aspire to?

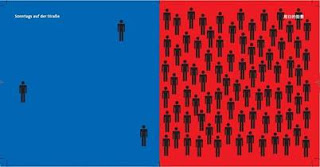

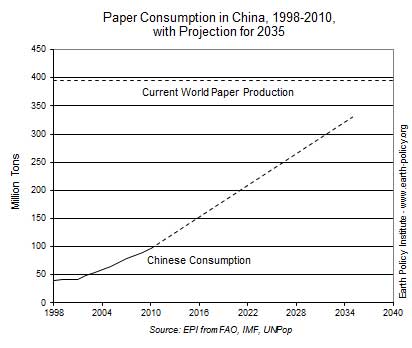

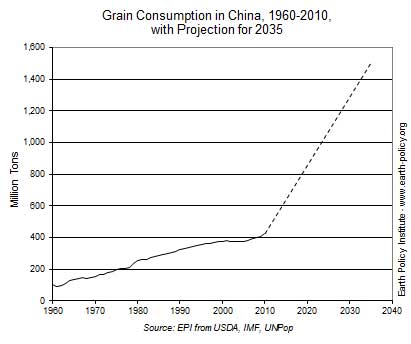

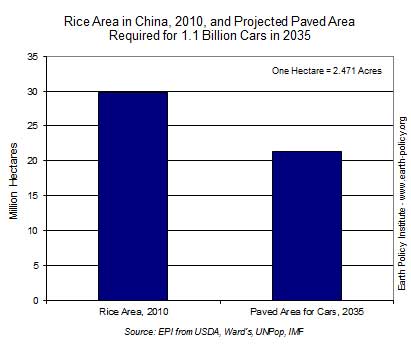

The fourth and final problem with the Myth of Development is a terminal

defect. Citizens in countries such as China and India are encouraged to join the

middle class and live "Western" lifestyles. As benign as it sounds, this goal is

completely impossible. Simply put, there are not enough natural resources on

this planet to sustain such an increase in consumption.

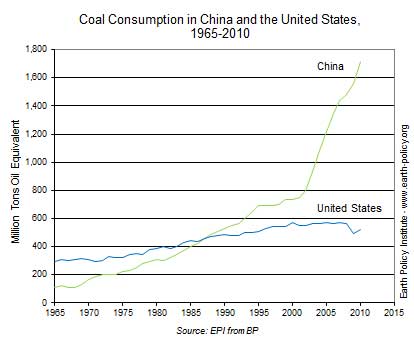

According to

World Bank figures, in 2008 Americans, on average, used 87,216 kilowatt hours of

electricity. The average Chinese used 18,608 kilowatt hours, and the average

Indian 6,280. All three countries depend primarily on coal for electricity. To

bridge the gap between these levels of resource utilization of would entail

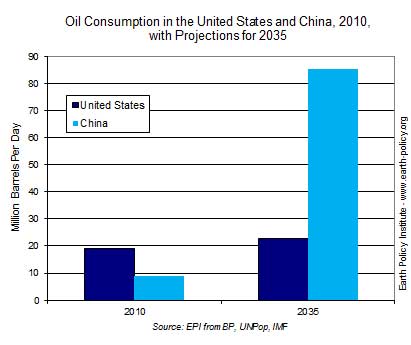

environmental catastrophe and global shortages on an unimaginable scale. Coal is

just one example - one could also look at oil, lumber, or meat consumption.

Indeed, many of the fundamental challenges facing the world economic system -

such as rising food and fuel costs - are directly related to economic

development.

The Development Deception is perpetuated by international

corporations and national governments. Resource mining, production, and

overconsumption are the basis for the current globalized economic system. Human

beings are classified as "consumers", because overconsumption entails short-term

profit.

Rich nations leverage their "developed" status to influence

poorer nations, while the governments of these poor nations use the promise of

development to maintain political power. None of this propaganda changes the

fact that it is grossly misleading for the nations who over-consume the Earth’s

finite resources to be considered developed.

Advocates of The

Development Myth may point to science as a savior. We are constantly told that

new inventions will allow for more efficient use of resources, or allow for

sustainable consumption patterns. This argument provides only false hope. We

cannot speculate our way out of environmental pollution and a collapsing natural

resource base. Unless and until new "green" technology actually exists and is

utilized, science is actually exacerbating ecological disaster.

Recently, the Human Development Index (HDI) has been promoted as a more

"human-centered" alternative to GDP as a metric for measuring development. HDI

uses data on life expectancy, literacy, number of years in school, and GDP to

determine the development status of a country. Although this presents a useful

alterative, the continued use of GDP as a basis for measuring development is

HDI’s fundamental flaw. Unsustainable consumption of finite resources cannot

reasonably be classified as "development".

What is the viable

alternative to the Development Myth? Bhutan has advocated Gross National

Happiness as an alternative goal to increasing GDP per capita. Citizens are

asked about their Subjective Well Being in order to establish Gross National

Happiness. Obviously this measurement is difficult to define and numerate, and

ignores problems such as illiteracy and extreme poverty. However, it does point

in the right direction.

Development needs to be redefined in order to

account for human physical and emotional well-being as well as environmental

sustainability. Otherwise it is only a lie, and a dangerous one at that. To seek

economic advance at the expense of human interests and future generations is a

recipe for global disaster.

When extreme wealth is challenging extreme

poverty as the bane of human existence, a revolution of values is needed. We as

a species must advance values of conservation, and teach people to live within

the means of the productive capacity of our planet. No longer can the scramble

for nonrenewable resources be viewed as a zero-sum game. Human beings need to

develop solidarity on a global scale. Citizens of wealthy nations must learn to

live with less.

The most important development is that of the

individual. Social and spiritual harmony is the antidote to the Development

Deception, for all traditions encourage compassion and warn of the destructive

power of greed. To quote LaoZi (as translated by D C Lau):

There is no crime greater than having too many desires;

There

is no disaster greater than not being content;

There is no misfortune

greater than being covetous.

Hence in being content, one will always have

enough.

Brendan P O'Reilly is a China-based writer

and educator from Seattle. He is author of The Transcendent Harmony.