Just before midnight on New Year’s Eve, authorities in the north-east Indian state of Assam published a list of 19 million names. But not Hanif Khan’s.

Early the next morning police found Khan, a taxi driver from Cachar district, dead from an apparent suicide. “I am sure he killed himself after he found his name missing,” his wife Rushka says.

Two years ago, Assam, a lush state bordering Bhutan and Bangladesh, embarked on a vast exercise: to identify every resident who could demonstrate roots in the state before March 1971.

And deport anyone who couldn’t.

An unfinished draft was released on 31 December – minus the names of 14 million other residents. Officials have stressed the final list will include millions more names, but the process is sparking anxiety in Assam, and warnings Indiamight be about to manufacture tens of thousands of stateless people.

Khan, 40, had grown increasingly tense in the weeks leading to the publication of the draft. Though he was born in Assam to an Indian mother, his father was an Afghan national who had long since drifted home.

Hanif Khan, a driver from Cachar district in Assam, India, who was found dead on 1 January, 2018. Photograph: Supplied

“He told me many times that the documents he presented to prove he was a citizen of India were perhaps not enough,” his wife said.

Assam is building a new detention centre to process the “foreigners” it plans to evict in the coming years. At least 2,000 people are already detained in six facilities across the state.

Khan often mentioned the detention centres, and had started to panic at the sight of police cars near his home, Rushka says. “He was extremely frightened. Every day he told me that police would arrest him and push him to Bangladesh.”

By December he was skipping meals and turning down driving jobs in unfamiliar places. Five hours before the list was published, his wife says, he vanished.

The eastern Indian border with Bangladesh traverses five states and more than 4,000km. For centuries until the partition of the subcontinent in 1947, human traffic flowed freely across the territory. In smaller numbers, people have continued crossing in the decades after: Indian security agencies estimate about 15 million Bangladesh citizens work and live in India without authorisation.

Just as with porous borders elsewhere, the flow of migrants from Bangladesh inflames Indian passions. Border guards were accused of gunning down nearly 1,000 people, most of them suspected smugglers, in the decade to 2010. A barbed-wire fence, bolstered in parts by floodlights and cameras, has been under construction since the mid-1980s and will eventually stretch more than 3,300km.

Resentment has been most acute in Assam, where it sparked an anti-migrant movement in the 1980s that paralysed the state and eventually won government. It also fuelled one of India’s worst single-day massacres since partition: a frenzied seven-hour pogrom in a clutch of Muslim villages that left at least 1,800 people dead.

“Here, foreigners are like people from a different planet,” says Aman Wadud, a lawyer who represents people accused of migrating illegally.

Assamese residents complain thousands of migrants have found their way onto voting rolls and take jobs and land from locals. “In the past two decades, loads of Muslims from Bangladesh have settled around us,” says Pankaj Saha, a retailer from Dhubri district.

“Twenty years ago, Hindus formed 75% of my town’s population. Today, the Muslims are in majority.”

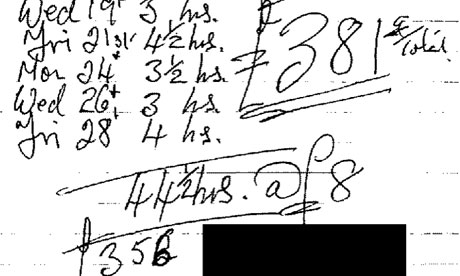

Proving the identities of more than 30 million people – many bearing handwritten records, or none at all – has fallen to Prateek Hajela, a senior civil servant. “We have received around 65 million documents,” he says from his office in Guwahati, the Assam capital.

The fate of those who fail to win citizenship is outside his control, he says. “What happens to those people who have applied and are not found to be eligible, I can’t say.”

Yet this is the question dogging the process. Tribunals have already declared about 90,000 people in Assam to be foreigners, according to statistics obtained by IndiaSpend, a data journalism initiative.

Only a few dozen have been deported in recent years – Bangladesh and India have no formal repatriation agreement – and officials admit many turn around and return at the first opportunity.

Another 38,000 of those declared to be foreigners in Assam have disappeared into the community, according to police records. Thousands more claim to be wrongly accused and are awaiting citizenship hearings.

The prospect of being suddenly arrested as a foreigner and languishing for years in a detention camp is worrying Bengali Muslims in particular. “There is enormous fear and apprehension in the community,” Wadud says.

Other than Hanif’s, at least two others suicides have been linked to the process. “I am telling people, we need to wait for the second list,” says Subimal Bhattacharjee, an analyst who runs welfare schemes in the state. “A significant number of names will be added. Verification is still going on.”

When the government finally publishes the full list of citizens on 31 May, the ranks of foreigners in Assam could swell by tens of thousands – with no clear plan yet of what to do with them.

The Assam chief minister, Sarbananda Sonowal, said in an interview last month that foreigners would lose constitutional rights. “They will have only one right – human rights as guaranteed by the the UN that include food, shelter and clothing.”

The issue of deportation, he said, “will come later”.

Officials in the Indian home ministry declined to comment on the record but said their expectation was that Bangladesh would take back any of its citizens, as it currently does on a case-by-case basis.

Bangladesh says it is not aware of any citizens living illegally in Assam, and that India has never raised the prospect of mass deportations from the state. An official at the country’s high commission in Delhi confirmed this position was unchanged.

“Deportations will never happen,” Wadud says. “Bangladesh will never accept these people. I can’t imagine what will happen to them. They will become stateless people with no rights whatsoever.”