'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label funding. Show all posts

Showing posts with label funding. Show all posts

Wednesday, 21 February 2024

Thursday, 15 February 2024

Wednesday, 20 September 2023

Sunday, 4 December 2022

Saturday, 17 September 2022

Wednesday, 5 January 2022

Sunday, 2 January 2022

Monday, 13 September 2021

Tuesday, 23 February 2021

Bleeding from Shylock’s cut

Jawed Naqvi in The Dawn

SHYLOCK is the big business, Antonio, the political parties. Let’s throw in Portia, symbolising law and justice, but which mostly eludes Indians currently. The news is heart-warming in the interregnum though. A brilliant woman journalist won a tenacious legal battle with an alleged sex predator of a powerful social echelon. And octogenarian leftist poet Varavara Rao got bail too, albeit for six months.

But Rao’s comrades, India’s most brilliant and selfless souls, are cramming the jails. A battery of leftist intellectuals and lawyers along with a merrily self-effacing octogenarian Jesuit priest stand accused of plotting to murder the prime minister in a laughably bizarre plot. Others are facing sedition charges for orchestrating communal violence in Delhi, which their rivals actually waged under police protection.

An American newspaper has revealed how the dubious assassination plot was structured around hacked computers that were used to plant the “evidence” of the purported crime. So, the victories here and there are welcome aberrations — happy aberrations — in a system that stands entrenched against equal rights and dignity for women and which ambushes dissenting citizens at will.

It’s no secret that major political parties receive funds from big business, which becomes a fertile ground for quid pro quo. In fact, it’s a curious rule of thumb that the parties whose leaders are in jail or face charges for alleged graft, are precisely the ones that the corporate lobbies shunned, and, therefore, did not favour with their largesse. It is also likely that the leaders didn’t accept the implied quid pro quo and chose to suffer.

It’s a bit like the movie industry. If one didn’t pick the money from the usurious market the movie is likely never going to find a theatre to screen it. Mayawati and Lalu Yadav are a case in point of politicians who have been made an example of for seeking alternative routes of raising money, tainted money, to fight costly elections, and which they mostly won. Portia will have to be more innovative than leaning on her fabled court craft and throwing in a clever interpretation of law to tilt the argument. Today, she has to weigh the cases as presented.

Chara ghotala or fodder scam is up for public scrutiny and trial by media, a bail-less crime, but an opaque defence deal has to be decided for reasons of national security through sealed envelopes in highest court rooms. This, therefore, is a political battle and has to be fought politically. It is far-fetched to think of defeating a closet patriarchy or a renegade state in a court battle.

In this regard, a key component of Prime Minister Modi’s hare-brained demonetisation move had a clever edge. He mopped up 85 per cent of India’s cash on Nov 8, 2016. The Uttar Pradesh assembly polls began on Feb 11, 2017. By cancelling big currency notes on the eve of a huge election, which Uttar Pradesh always is, he sucked out a vital resource the rivals needed to give him a good fight.

Why don’t Indian parties crowd-fund as some, but only some, sections of the left do? Even in the heartland of capitalism in the United States, Bernie Sanders could come tantalisingly close to becoming president with crowd funding. Delhi’s Aam Aadmi Party came to power with the help of this mostly shunned method of raising electoral funds. In the bargain, AAP inspired donors to see themselves as stakeholders in the great endeavour.

We read in the morning paper that India’s main opposition Congress party has run out of money. Elections are due in key states where the party could do well, primarily Assam, with clever handling. It’s a wrong time not to have money. West Bengal, Tamil Nadu, Pondicherry and Kerala are also up for polls.

Being in penury, or near penury, is, however, a good sign for the Congress party and may not be such a bad idea for India’s democracy either. Remember the tycoons muscling their way through pliable media contacts to claim cabinet berths for their acolytes in the second innings of the Congress-led alliance of Manmohan Singh? The ministry of telecommunications was crucial to the quest. And with all the deals being done to monopolise data and e-commerce today, the stakes were bound to be high. The BJP has emerged as the monopoly beneficiary of corporate donations, not least by tweaking the law to make the transactions opaque. No surprise there.

A great reason for the Congress’s financial crunch is Rahul Gandhi’s decision to make a direct connection between India’s prevailing economic crisis and Mr Modi’s patronage of his crony capitalist friends. Protesting farmers, dissenting intellectuals and assorted environmentalists across the world have seen through the plot. (Whoever can see the plot is an enemy of the state.)

On the flip side of the Congress’s course correction under Gandhi, an interview was published of Punjab’s Congress Chief Minister Amarinder Singh. He is rowing back from the bold demands by the farmers for the repeal of pro-business farm laws. Singh favours suspending the laws for two years instead of annulling them. The India Today magazine did some fact-checking to show that Singh had not met Modi’s friend Mukesh Ambani, as claimed, a day ahead of the nationwide strike by the farmers. The cordial picture of the two was from 2017.

Amarinder’s challenger in Congress is cricketer-turned-politician Navjot Sidhu, a vocal critic of big business. Shylock is hemorrhaging India. Rahul Gandhi is losing his MLAs to corporate-political pelf, the latest casualty being his government in Pondicherry. It’s time he went to the people with the bowl, an agreeable way to involve them in his bold analysis of the country’s crisis. He can start to stitch the wounds, not as a grand leader for which he must win a mandate, but as a caring citizen like those languishing in jails. The Congress will be the richer for it. Good for Portia too.

SHYLOCK is the big business, Antonio, the political parties. Let’s throw in Portia, symbolising law and justice, but which mostly eludes Indians currently. The news is heart-warming in the interregnum though. A brilliant woman journalist won a tenacious legal battle with an alleged sex predator of a powerful social echelon. And octogenarian leftist poet Varavara Rao got bail too, albeit for six months.

But Rao’s comrades, India’s most brilliant and selfless souls, are cramming the jails. A battery of leftist intellectuals and lawyers along with a merrily self-effacing octogenarian Jesuit priest stand accused of plotting to murder the prime minister in a laughably bizarre plot. Others are facing sedition charges for orchestrating communal violence in Delhi, which their rivals actually waged under police protection.

An American newspaper has revealed how the dubious assassination plot was structured around hacked computers that were used to plant the “evidence” of the purported crime. So, the victories here and there are welcome aberrations — happy aberrations — in a system that stands entrenched against equal rights and dignity for women and which ambushes dissenting citizens at will.

It’s no secret that major political parties receive funds from big business, which becomes a fertile ground for quid pro quo. In fact, it’s a curious rule of thumb that the parties whose leaders are in jail or face charges for alleged graft, are precisely the ones that the corporate lobbies shunned, and, therefore, did not favour with their largesse. It is also likely that the leaders didn’t accept the implied quid pro quo and chose to suffer.

It’s a bit like the movie industry. If one didn’t pick the money from the usurious market the movie is likely never going to find a theatre to screen it. Mayawati and Lalu Yadav are a case in point of politicians who have been made an example of for seeking alternative routes of raising money, tainted money, to fight costly elections, and which they mostly won. Portia will have to be more innovative than leaning on her fabled court craft and throwing in a clever interpretation of law to tilt the argument. Today, she has to weigh the cases as presented.

Chara ghotala or fodder scam is up for public scrutiny and trial by media, a bail-less crime, but an opaque defence deal has to be decided for reasons of national security through sealed envelopes in highest court rooms. This, therefore, is a political battle and has to be fought politically. It is far-fetched to think of defeating a closet patriarchy or a renegade state in a court battle.

In this regard, a key component of Prime Minister Modi’s hare-brained demonetisation move had a clever edge. He mopped up 85 per cent of India’s cash on Nov 8, 2016. The Uttar Pradesh assembly polls began on Feb 11, 2017. By cancelling big currency notes on the eve of a huge election, which Uttar Pradesh always is, he sucked out a vital resource the rivals needed to give him a good fight.

Why don’t Indian parties crowd-fund as some, but only some, sections of the left do? Even in the heartland of capitalism in the United States, Bernie Sanders could come tantalisingly close to becoming president with crowd funding. Delhi’s Aam Aadmi Party came to power with the help of this mostly shunned method of raising electoral funds. In the bargain, AAP inspired donors to see themselves as stakeholders in the great endeavour.

We read in the morning paper that India’s main opposition Congress party has run out of money. Elections are due in key states where the party could do well, primarily Assam, with clever handling. It’s a wrong time not to have money. West Bengal, Tamil Nadu, Pondicherry and Kerala are also up for polls.

Being in penury, or near penury, is, however, a good sign for the Congress party and may not be such a bad idea for India’s democracy either. Remember the tycoons muscling their way through pliable media contacts to claim cabinet berths for their acolytes in the second innings of the Congress-led alliance of Manmohan Singh? The ministry of telecommunications was crucial to the quest. And with all the deals being done to monopolise data and e-commerce today, the stakes were bound to be high. The BJP has emerged as the monopoly beneficiary of corporate donations, not least by tweaking the law to make the transactions opaque. No surprise there.

A great reason for the Congress’s financial crunch is Rahul Gandhi’s decision to make a direct connection between India’s prevailing economic crisis and Mr Modi’s patronage of his crony capitalist friends. Protesting farmers, dissenting intellectuals and assorted environmentalists across the world have seen through the plot. (Whoever can see the plot is an enemy of the state.)

On the flip side of the Congress’s course correction under Gandhi, an interview was published of Punjab’s Congress Chief Minister Amarinder Singh. He is rowing back from the bold demands by the farmers for the repeal of pro-business farm laws. Singh favours suspending the laws for two years instead of annulling them. The India Today magazine did some fact-checking to show that Singh had not met Modi’s friend Mukesh Ambani, as claimed, a day ahead of the nationwide strike by the farmers. The cordial picture of the two was from 2017.

Amarinder’s challenger in Congress is cricketer-turned-politician Navjot Sidhu, a vocal critic of big business. Shylock is hemorrhaging India. Rahul Gandhi is losing his MLAs to corporate-political pelf, the latest casualty being his government in Pondicherry. It’s time he went to the people with the bowl, an agreeable way to involve them in his bold analysis of the country’s crisis. He can start to stitch the wounds, not as a grand leader for which he must win a mandate, but as a caring citizen like those languishing in jails. The Congress will be the richer for it. Good for Portia too.

Saturday, 7 July 2018

China’s tech funding boom: is Europe asleep on the job?

Evgeny Morozov in The Guardian

In matters of industrial strategy and international competition, there’s no contrast starker than that between the hapless resignation of Europe and the steely determination of China. Unsurprisingly, it has been China – not Europe – that has proposed, with little success, forming a common front against Donald Trump’s trade tantrums. Even Washington’s bullying cannot awaken European policymakers from their slumber – or, as seems more likely, their moderately lubricated afternoon nap.

Hardly a week passes without a new alarming announcement that Beijing has managed to outmanoeuvre Brussels in yet another domain. Last week brought three such developments.

First, China Merchants Group, a state-owned company, joined forces with SPF Group and Centricus – asset managers based in Beijing and London respectively – to form a $15bn fund to compete with SoftBank’s $100bn Vision Fund, launched to invest in the most promising technology firms worldwide. This comes weeks after Sequoia Capital, America’s finest venture capital firm, closed the first round of fundraising on its $8bn Vision Fund alternative.

Second, Contemporary Amperex Technology, one of the largest manufacturers of lithium-ion batteries in China and a major beneficiary of its government’s efforts to steer this industry towards world leadership, signed a €1bn deal with BMW, with the intention of building its own factory in Europe to satisfy soaring demand for its batteries.

Daimler, another crown jewel of the German car industry, is now reportedly considering placing a similar order.

Third, Bolloré Group, one of France’s most important conglomerates, with activities spanning paper, energy and logistics businesses, entered a deal with Chinese technology giant Alibaba. Bolloré is hoping to use Alibaba’s sprawling cloud-computing empire across its operations, including in its battery-making division.

There is a neutral, even positive, interpretation of these developments. European capital – British in the first case, German in the second, French in the third – is taking advantage of lucrative opportunities. China just happens to offer more of them at the moment.

And yet, each of the three developments reveals major gaps in Europe’s industrial strategy. It’s one thing for European capital to be passively invested into most promising robotics or AI projects worldwide: Daimler, for example, is one of the few European backers of the Vision Fund. It’s quite another thing to be doing it with the goal of creating Europe’s own champions in these fields.

The European Commission’s strategy on artificial intelligence, published in April 2018, rests on the untested assumption that Brussels will succeed in mobilising nearly €18bn of private capital to complement a couple of billions that will be found in existing European programs. This, however, will require convincing the likes of Daimler – whose biggest shareholder today is China’s Geely – that their investments should go to some European tech fund, rather than to SoftBank or China Merchants Group.

It’s a challenge similar to Europe’s efforts, unsuccessful so far, to push European industry towards creating a European manufacturer of batteries for electric cars, if only to minimise its reliance on China and South Korea (the European Battery Alliance, an industry-wide initiative championed by the European commission, was launched last year, but has not borne much fruit yet).

European leaders seem to recognise the battery challenge – and so do Germany’s powerful trade unions – but it’s hard to see how it will be solved when the likes of BMW and Daimler keep placing billion dollar-orders with Chinese battery manufacturers.

The story on cloud computing, increasingly bundled with artificial intelligence services, is not much different: even if the European industry wanted to turn away from Amazon or Microsoft and use a European provider, it just does not have much choice. It is essentially hemmed in by American and Chinese giants.

This dependence was easier to justify when global trade was running smoothly and all industries looked alike (looked equally unimportant from the perspective of national or regional interests). Now that the European car industry finds itself under heavy fire from Trump, Brussels is severely constrained in its response.

Artificial intelligence: €20bn investment call from EU commission

When Trump threatens Europe’s most important industry, the logical thing to do would be to threaten retaliation against America’s own most important industry, which, whatever Trump himself believes, is actually based in Silicon Valley and Seattle, not Detroit.

This, however, is not an option: no one is going to believe that Europe, which has inserted services from Alphabet, IBM, Microsoft and Amazon deep into the infrastructure of its hospitals, energy grids, transportation systems, and universities is going to shut them off.

The best it can hope for, at this point, is to diversify its reliance on the US giants by doing some business with the Chinese ones.

None of this bodes well for Europe’s ability to remain at the centre of the global economy. Its industrial giants will not fade away but they will be increasingly dominated by foreign owners and foreign technology. While, in the rosier days of globalisation, this might even have been hailed as laudable, under today’s new normal this strategy borders on the suicidal. Those afternoon naps of European policymakers increasingly look like a coma.

In matters of industrial strategy and international competition, there’s no contrast starker than that between the hapless resignation of Europe and the steely determination of China. Unsurprisingly, it has been China – not Europe – that has proposed, with little success, forming a common front against Donald Trump’s trade tantrums. Even Washington’s bullying cannot awaken European policymakers from their slumber – or, as seems more likely, their moderately lubricated afternoon nap.

Hardly a week passes without a new alarming announcement that Beijing has managed to outmanoeuvre Brussels in yet another domain. Last week brought three such developments.

First, China Merchants Group, a state-owned company, joined forces with SPF Group and Centricus – asset managers based in Beijing and London respectively – to form a $15bn fund to compete with SoftBank’s $100bn Vision Fund, launched to invest in the most promising technology firms worldwide. This comes weeks after Sequoia Capital, America’s finest venture capital firm, closed the first round of fundraising on its $8bn Vision Fund alternative.

Second, Contemporary Amperex Technology, one of the largest manufacturers of lithium-ion batteries in China and a major beneficiary of its government’s efforts to steer this industry towards world leadership, signed a €1bn deal with BMW, with the intention of building its own factory in Europe to satisfy soaring demand for its batteries.

Daimler, another crown jewel of the German car industry, is now reportedly considering placing a similar order.

Third, Bolloré Group, one of France’s most important conglomerates, with activities spanning paper, energy and logistics businesses, entered a deal with Chinese technology giant Alibaba. Bolloré is hoping to use Alibaba’s sprawling cloud-computing empire across its operations, including in its battery-making division.

There is a neutral, even positive, interpretation of these developments. European capital – British in the first case, German in the second, French in the third – is taking advantage of lucrative opportunities. China just happens to offer more of them at the moment.

And yet, each of the three developments reveals major gaps in Europe’s industrial strategy. It’s one thing for European capital to be passively invested into most promising robotics or AI projects worldwide: Daimler, for example, is one of the few European backers of the Vision Fund. It’s quite another thing to be doing it with the goal of creating Europe’s own champions in these fields.

The European Commission’s strategy on artificial intelligence, published in April 2018, rests on the untested assumption that Brussels will succeed in mobilising nearly €18bn of private capital to complement a couple of billions that will be found in existing European programs. This, however, will require convincing the likes of Daimler – whose biggest shareholder today is China’s Geely – that their investments should go to some European tech fund, rather than to SoftBank or China Merchants Group.

It’s a challenge similar to Europe’s efforts, unsuccessful so far, to push European industry towards creating a European manufacturer of batteries for electric cars, if only to minimise its reliance on China and South Korea (the European Battery Alliance, an industry-wide initiative championed by the European commission, was launched last year, but has not borne much fruit yet).

European leaders seem to recognise the battery challenge – and so do Germany’s powerful trade unions – but it’s hard to see how it will be solved when the likes of BMW and Daimler keep placing billion dollar-orders with Chinese battery manufacturers.

The story on cloud computing, increasingly bundled with artificial intelligence services, is not much different: even if the European industry wanted to turn away from Amazon or Microsoft and use a European provider, it just does not have much choice. It is essentially hemmed in by American and Chinese giants.

This dependence was easier to justify when global trade was running smoothly and all industries looked alike (looked equally unimportant from the perspective of national or regional interests). Now that the European car industry finds itself under heavy fire from Trump, Brussels is severely constrained in its response.

Artificial intelligence: €20bn investment call from EU commission

When Trump threatens Europe’s most important industry, the logical thing to do would be to threaten retaliation against America’s own most important industry, which, whatever Trump himself believes, is actually based in Silicon Valley and Seattle, not Detroit.

This, however, is not an option: no one is going to believe that Europe, which has inserted services from Alphabet, IBM, Microsoft and Amazon deep into the infrastructure of its hospitals, energy grids, transportation systems, and universities is going to shut them off.

The best it can hope for, at this point, is to diversify its reliance on the US giants by doing some business with the Chinese ones.

None of this bodes well for Europe’s ability to remain at the centre of the global economy. Its industrial giants will not fade away but they will be increasingly dominated by foreign owners and foreign technology. While, in the rosier days of globalisation, this might even have been hailed as laudable, under today’s new normal this strategy borders on the suicidal. Those afternoon naps of European policymakers increasingly look like a coma.

Wednesday, 11 April 2018

Sunday, 29 October 2017

Dons, donors and the murky business of funding universities

John Lloyd in The Financial Times

The University of Oxford is in constant need of money — and it takes an approach to raising it that oscillates between the severe and the relaxed. Those familiar with its procedures say many would-be donors have been turned away. No names are given, outside of senior common room gossip. “Oxford doesn’t need to compromise,” says Sir Anthony Seldon, vice-chancellor of the independent Buckingham University. “People want to be associated with it.” But that confident sense that the great universities will do the right thing has been called into question by a Swedish academic who has thrown down the gauntlet to one of Oxford’s most prominent donors.

The University of Oxford is in constant need of money — and it takes an approach to raising it that oscillates between the severe and the relaxed. Those familiar with its procedures say many would-be donors have been turned away. No names are given, outside of senior common room gossip. “Oxford doesn’t need to compromise,” says Sir Anthony Seldon, vice-chancellor of the independent Buckingham University. “People want to be associated with it.” But that confident sense that the great universities will do the right thing has been called into question by a Swedish academic who has thrown down the gauntlet to one of Oxford’s most prominent donors.

For many centuries the deal has been clear: donations buy gratitude and even a named chair or library, but no rights to influence the running of the institution. In return, barring evidence of illegality, the university will not probe the funder’s finances. “You don’t have to like sponsors,” says the Canadian scholar Margaret MacMillan, an admired contemporary historian and former warden of St Antony’s College, Oxford. “But if they don’t interfere with your teaching and your choice of colleagues, then the rest is their own affair.”

The Rhodes scholarship is a case in point. It began in 1902 with a bequest from Cecil Rhodes, the enthusiastic imperialist who argued that Anglo-Saxons deserved to be the dominant global race. His scholarship was founded to bring “the whole of the uncivilised world under British rule”, by funding young men to Oxford. Two years ago a South African Rhodes scholar, Ntokozo Qwabe, started a campaign to recognise the “colonial genocide” underpinning Rhodes’ wealth. He called for the removal of his statue from Oriel College, Rhodes’ alma mater. The campaign escalated, but the university and college resisted and the statue still stands.

You cannot accept stolen money, but who is to decide what is stolen? Money from the oligarchs?

A more recent bequest, beginning with £20m in 1985 and rising to over £50m, is that of the Syrian-born businessman Wafic Saïd to Oxford’s business school, which bears his name. With high-level contacts in the Saudi royal family, Saïd had helped to arrange the Al-Yamamah contracts between Saudi Arabia and British Aerospace and other UK companies from the mid-1980s onwards, worth some £44bn. In the 2000s it emerged that millions of pounds had been paid to senior Saudi royals to smooth the deal. BAE agreed to pay over £250m in the US in 2010, after the Department of Justice found it guilty of “intentionally failing to put appropriate anti-bribery preventive measures in place”. No wrongdoing was proved against Saïd, who said he had received no commissions for assisting in the deal. Last year, he opened legal proceedings against Barclays Bank, which had forced him to close several accounts, and had told him he was no longer welcome as a customer. (He later dropped the lawsuit after the bank apologised and confirmed the closures had been a business decision that was not based on any wrongdoing in relation to account activity.)

The traditional argument justifying such relationships is ensuring a robust division between gift and subsequent influence. The economist and FT commentator John Kay, the first director of the Saïd Business School (1997-99), says he takes “a relaxed view of the relationship between the leadership of a university or college and the donor. It’s rare to have a very rich donor who has accumulated his wealth by simple hard work and dedication to honest business. There’s often something like monopolistic practices. You cannot accept stolen money, but who is to decide what is stolen? Money from the oligarchs? From Nigerian businessmen?”

Seldon at Buckingham adds, “Even if it’s bad money, it can serve good causes. The key thing is that there are no conditions attached, and that there is a clear statement of the establishment of a firewall between the money and the decisions of the institute. We would all be in a pickle if we were to be morally pure.”

Bo Rothstein, a former professor at Oxford University who resigned his post in protest against one of its funders But moral purity has come to Oxford, in the shape of Professor Bo Rothstein. A fellow of Nuffield College, Rothstein is a Swedish sociologist whose work has centred on ethical issues, most recently on studies of corruption in government. In 2015, he joined the faculty at the Blavatnik School of Government — where, in early August, he learnt that Len Blavatnik, the billionaire Ukrainian-born businessman whose £75m gift had founded the school, had given $1m to help finance Donald Trump’s inauguration. Blavatnik, one of Britain’s richest men, was knighted this year for services to philanthropy: he has given large sums to the Tate Modern and, with the New York Academy of Sciences, has established the Blavatnik Award for Young Scientists. After a pause for reflection, Rothstein resigned in protest.

Rothstein believes Trump is an existential danger to western values. To become entangled financially with such a man in any way, he argues, is an affront to both universal and university values. “I teach about the importance of rights,” he says. “How am I to explain to a student why I am giving legitimacy, by teaching at the school, to one who gives money to him? It’s impossible.” How far would you take this argument, he adds. “Would you take money from one who was a Nazi? Would you have a Hermann Göring chair of aviation?”

Rothstein’s challenge to Oxford’s see-no-evil consensus has brought him into conflict with one of the university’s brightest stars, the economist and international-relations scholar Professor Ngaire Woods. It was Woods who conceived of and secured the funding for the Blavatnik School of Government, becoming its founding director in 2011.

She disputes almost everything Rothstein says about the immediate aftermath of his resignation — something he refers to as an “excommunication”, because he was asked to leave the school very soon after his resignation. On the central issue, she says that “we do not tell our donors how to exercise their political points of view; they do not tell us how to run the institute. Len Blavatnik has never said anything to me about what I should do or how I should teach. Never. Not once. There was a representative of the donor on the building committee for the institute, as is the Oxford practice, and that has been the extent of it.”

Woods believes Rothstein had not grasped the difference between supporting Trump’s campaign and giving to the inauguration. “Lots of people give money to the inauguration, because it can’t be paid for from government funds,” she points out. “You cannot seriously think that the institute is in some way linked to Trump. We teach our students to try to get the facts right, to reason and to learn from diversity. We recently held a ‘challenges to government’ conference, in which all the issues of governance were debated. We have an open, argumentative centre.”

Rothstein’s campaign has been a lonely one, not least given that established opinion in Oxford is squarely against him. Macmillan says that “to give money for Trump’s inaugural was quite legal, a perfectly sensible thing to do. I think he [Rothstein] put himself in an indefensible position.” Kay commends Rothstein for having the courage of his convictions, and “not engaging in a protest which costs nothing in the way of harm to the protester, but accepting the damage this will do to his position”, but he believes he was wrong to act as he did. At Buckingham, Seldon says: “I have sympathy for what he has done, but if the Blavatnik institute gets money that is unattached, and it’s clear there must be no influence, then that is OK.”

This consensual view is anathema to Rothstein, a Luther among Renaissance popes. “Trump is a very serious threat to liberal democracy. My colleagues think it’s not too serious. Some say we shouldn’t oppose him head on, but we should just give the platform to strong liberals and democrats. But I am not keen on that. It’s trying to take a middle course which, with Trump, now you cannot take.”

Rothstein sees the infamous case involving the London School of Economics as proving his point. In 2008, the LSE’s Global Governance Centre accepted a donation of £1.5m from Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, son of the long-time despot of Libya, Muammer Gaddafi.

Amid charges that a PhD had been awarded to Saif improperly, and after a speech in Tripoli in 2011 in which he promised “rivers of blood” to flow if protests against his father’s regime did not stop, the LSE acknowledged it had erred in pursuing the relationship and in taking the money. The then-director, Sir Howard Davies, resigned. Says Rothstein: “There are of course donors whose behaviour you cannot just ignore and say, ‘Well, it’s their business.’ ”

Rothstein has at least one prominent supporter in the academy, back in his native Sweden: the president of the Stockholm School of Economics, Lars Strannegård. “I think he was right to do it. Things which a year ago were thought not even to be allowed to be said are now daily announced from the White House. This strikes at the core of what universities do. It is like when you dip a watercolour brush into water — the first time it is slightly darkened, then more, and more until it is completely dark.”

The Blavatnik affair finds an echo in the 1951 CP Snow novel, The Masters. Set in a Cambridge college in 1937, it concerns a struggle over the election of a new master — the two main contestants being an establishment figure seeking to bolster his chances by attracting a donation, and a radical scientist determined the college should take a stance against the steady advance of fascism.

But universities are now far from Snow’s times. Those who now run them attest to a much more harried life than in the past. The state has retreated from full funding — universities charge fees, and most have created units that raise money — but it now expects higher teaching and research standards. At the same time as the universities have come under more intense financial pressure, their student bodies have become more combative. Aside from the “Rhodes Must Fall” campaign, there has been a rash of “no platforming” incidents in which controversial speakers have been barred from appearing on campus.

More threatening still are the campaigns to force universities to divest themselves of investment considered unethical. Cambridge university has ceased investment in coal and tar sand “heavy” oil, but the pressure to go further is intensifying. Many students, faculty members and influential figures including Rowan Williams, former Archbishop of Canterbury and now master of Magdalene College, are calling for Cambridge to divest from all energy companies. So far the university has resisted, but Nick Butler, a former senior executive in BP and now a visiting professor at King’s College London, believes the tide runs against them. “The universities don’t want to be told what to do with their money,” he says. “But I think that, since the protests will continue, more and more will give in.”

Money is power, but so is a university, especially one as storied as Oxford. Large donors are not always kept at arm’s length, and influences can be subtle, a question of implicit understandings more than explicit direction. They can also be fruitful: as a co-founder of the university’s Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (2006), whose funding comes largely from the Thomson Reuters Foundation, I think it right that Reuters representatives sit on the committees of the institute — balancing those who represent the interests of the university. The idea was, in part, to have the academy and the journalism trade interact and inform each other — not always without friction, but always with benefits.

Donor-ship is an increasingly complex business in the digital age. What once might have been a campus kerfuffle can become a global furore. Last month, Washington DC saw such a dispute when a scholar named Barry Lynn was fired from the New America Foundation think-tank (not attached to a university) by its chief executive, Anne-Marie Slaughter. Lynn had written a statement about Google and “other dominant platform monopolists” and called for more robust antitrust action against them. Google, a major funder of the foundation, complained via Eric Schmidt, executive chairman of its parent company, Alphabet, according to the New York Times. Slaughter, a former director of policy planning at the State Department, at first called the Times’ report false, then backtracked. She later conceded: “There are unavoidable tensions the minute you take corporation funding or foreign government funding.”

Universities must now manage tensions more actively than before; in doing so, all make deals and ethical zigzags. The two main protagonists in this updated CP Snow imbroglio deserve each other, for both are driven: Woods, by a desire to fashion her school into a world centre for the study of good governance; Rothstein, by a hyperactive political conscience that demanded a demonstrative act, essential to dramatise the scale of the disaster that, he believes, the Trump presidency presages. Two beliefs clash: one, that continuing to offer a rational-liberal education will maintain and expand rational-liberal governance; the other, that these very assumptions are being destroyed, and that larger protest must be made. Both are, at root, principled. Both cannot be right.

Sunday, 3 September 2017

Silicon Valley has been humbled. But its schemes are as dangerous as ever

Sex scandals, rows over terrorism, fears for its impact on social policy: the backlash against Big Tech has begun. Where will it end?

Evgeny Morozov in The Guardian

Just a decade ago, Silicon Valley pitched itself as a savvy ambassador of a newer, cooler, more humane kind of capitalism. It quickly became the darling of the elite, of the international media, and of that mythical, omniscient tribe: the “digital natives”. While an occasional critic – always easy to dismiss as a neo-Luddite – did voice concerns about their disregard for privacy or their geeky, almost autistic aloofness, public opinion was firmly on the side of technology firms.

Silicon Valley was the best that America had to offer; tech companies frequently occupied – and still do – top spots on lists of the world’s most admired brands. And there was much to admire: a highly dynamic, innovative industry, Silicon Valley has found a way to convert scrolls, likes and clicks into lofty political ideals, helping to export freedom, democracy and human rights to the Middle East and north Africa. Who knew that the only thing thwarting the global democratic revolution was capitalism’s inability to capture and monetise the eyeballs of strangers?

How things have changed. An industry once hailed for fuelling the Arab spring is today repeatedly accused of abetting Islamic State. An industry that prides itself on diversity and tolerance is now regularly in the news for cases of sexual harassment as well as the controversial views of its employees on matters such as gender equality. An industry that built its reputation on offering us free things and services is now regularly assailed for making other things – housing, above all– more expensive.

The Silicon Valley backlash is on. These days, one can hardly open a major newspaper – including such communist rags as the Financial Times and the Economist – without stumbling on passionate calls that demand curbs on the power of what is now frequently called “Big Tech”, from reclassifying digital platforms as utility companies to even nationalising them.

Meanwhile, Silicon Valley’s big secret – that the data produced by users of digital platforms often has economic value exceeding the value of the services rendered – is now also out in the open. Free social networking sounds like a good idea – but do you really want to surrender your privacy so that Mark Zuckerberg can run a foundation to rid the world of the problems that his company helps to perpetuate? Not everyone is so sure any longer. The Teflon industry is Teflon no more: the dirt thrown at it finally sticks – and this fact is lost on nobody.

Much of the brouhaha has caught Silicon Valley by surprise. Its ideas – disruption as a service, radical transparency as a way of being, an entire economy of gigs and shares – still dominate our culture. However, its global intellectual hegemony is built on shaky foundations: it stands on the post-political can-do allure of TED talks much more than in wonky thinktank reports and lobbying memorandums.

This is not to say that technology firms do not dabble in lobbying – here Alphabet is on a par with Goldman Sachs – nor to imply that they don’t steer academic research. In fact, on many tech policy issues it’s now difficult to find unbiased academics who have not received some Big Tech funding. Those who go against the grain find themselves in a rather precarious situation, as was recently shown by the fate of the Open Markets project at New America, an influential thinktank in Washington: its strong anti-monopoly stance appears to have angered New America’s chairman and major donor, Eric Schmidt, executive chairman of Alphabet. As a result, it was spun off from the thinktank.

Nonetheless, Big Tech’s political influence is not at the level of Wall Street or Big Oil. It’s hard to argue that Alphabet wields as much power over global technology policy as the likes of Goldman Sachs do over global financial and economic policy. For now, influential politicians – such as José Manuel Barroso, the former president of the European Commission – prefer to continue their careers at Goldman Sachs, not at Alphabet; it is also the former, not the latter, that fills vacant senior posts in Washington.

This will surely change. It’s obvious that the cheerful and utopian chatterboxes who make up TED talks no longer contribute much to boosting the legitimacy of the tech sector; fortunately, there’s a finite supply of bullshit on this planet. Big digital platforms will thus seek to acquire more policy leverage, following the playbook honed by the tobacco, oil and financial firms.

There are, however, two additional factors worth considering in order to understand where the current backlash against Big Tech might lead. First of all, short of a major privacy disaster, digital platforms will continue to be the world’s most admired and trusted brands – not least because they contrast so favourably with your average telecoms company or your average airline (say what you will of their rapaciousness, but tech firms don’t generally drag their customers off their flights).

And it is technology firms – American companies but also Chinese – that create the false impression that the global economy has recovered and everything is back to normal. Since January, the valuations of just four firms – Alphabet, Amazon, Facebook and Microsoft – have grown by an amount greater than the entire GDP of oil-rich Norway. Who would want to see this bubble burst? Nobody; in fact, those in power would rather see it grow some more.

The culture power of Silicon Valley can be gleaned from the simple fact that no sensible politician dares to go to Wall Street for photo ops; everyone goes to Palo Alto to unveil their latest pro-innovation policy. Emmanuel Macron wants to turn France into a startup, not a hedge fund. There’s no other narrative in town that makes centrist, neoliberal policies look palatable and inevitable at the same time; politicians, however angry they might sound about Silicon Valley’s monopoly power, do not really have an alternative project. It’s not just Macron: from Italy’s Matteo Renzi to Canada’s Justin Trudeau, all mainstream politicians who have claimed to offer a clever break with the past also offer an implicit pact with Big Tech – or, at least, its ideas – in the future.

Second, Silicon Valley, being the home of venture capital, is good at spotting global trends early on. Its cleverest minds had sensed the backlash brewing before the rest of us. They also made the right call in deciding that wonky memos and thinktank reports won’t quell our discontent, and that many other problems – from growing inequality to the general unease about globalisation – will eventually be blamed on an industry that did little to cause them.

Silicon Valley’s brightest minds realised they needed bold proposals – a guaranteed basic income, a tax on robots, experiments with fully privatised cities to be run by technology companies outside of government jurisdiction – that will sow doubt in the minds of those who might have otherwise opted for conventional anti-monopoly legislation. If technology firms can play a constructive role in funding our basic income, if Alphabet or Amazon can run Detroit or New York with the same efficiency that they run their platforms, if Microsoft can infer signs of cancer from our search queries: should we really be putting obstacles in their way?

In the boldness and vagueness of its plans to save capitalism, Silicon Valley might out-TED the TED talks. There are many reasons why such attempts won’t succeed in their grand mission even if they would make these firms a lot of money in the short term and help delay public anger by another decade. The main reason is simple: how could one possibly expect a bunch of rent-extracting enterprises with business models that are reminiscent of feudalism to resuscitate global capitalism and to establish a new New Deal that would constrain the greed of capitalists, many of whom also happen to be the investors behind these firms?

Data might seem infinite but there’s no reason to believe that the enormous profits made from it would simply smooth over the many contradictions of the current economic system. A self-proclaimed caretaker of global capitalism, Silicon Valley is much more likely to end up as its undertaker.

Evgeny Morozov in The Guardian

Just a decade ago, Silicon Valley pitched itself as a savvy ambassador of a newer, cooler, more humane kind of capitalism. It quickly became the darling of the elite, of the international media, and of that mythical, omniscient tribe: the “digital natives”. While an occasional critic – always easy to dismiss as a neo-Luddite – did voice concerns about their disregard for privacy or their geeky, almost autistic aloofness, public opinion was firmly on the side of technology firms.

Silicon Valley was the best that America had to offer; tech companies frequently occupied – and still do – top spots on lists of the world’s most admired brands. And there was much to admire: a highly dynamic, innovative industry, Silicon Valley has found a way to convert scrolls, likes and clicks into lofty political ideals, helping to export freedom, democracy and human rights to the Middle East and north Africa. Who knew that the only thing thwarting the global democratic revolution was capitalism’s inability to capture and monetise the eyeballs of strangers?

How things have changed. An industry once hailed for fuelling the Arab spring is today repeatedly accused of abetting Islamic State. An industry that prides itself on diversity and tolerance is now regularly in the news for cases of sexual harassment as well as the controversial views of its employees on matters such as gender equality. An industry that built its reputation on offering us free things and services is now regularly assailed for making other things – housing, above all– more expensive.

The Silicon Valley backlash is on. These days, one can hardly open a major newspaper – including such communist rags as the Financial Times and the Economist – without stumbling on passionate calls that demand curbs on the power of what is now frequently called “Big Tech”, from reclassifying digital platforms as utility companies to even nationalising them.

Meanwhile, Silicon Valley’s big secret – that the data produced by users of digital platforms often has economic value exceeding the value of the services rendered – is now also out in the open. Free social networking sounds like a good idea – but do you really want to surrender your privacy so that Mark Zuckerberg can run a foundation to rid the world of the problems that his company helps to perpetuate? Not everyone is so sure any longer. The Teflon industry is Teflon no more: the dirt thrown at it finally sticks – and this fact is lost on nobody.

Much of the brouhaha has caught Silicon Valley by surprise. Its ideas – disruption as a service, radical transparency as a way of being, an entire economy of gigs and shares – still dominate our culture. However, its global intellectual hegemony is built on shaky foundations: it stands on the post-political can-do allure of TED talks much more than in wonky thinktank reports and lobbying memorandums.

This is not to say that technology firms do not dabble in lobbying – here Alphabet is on a par with Goldman Sachs – nor to imply that they don’t steer academic research. In fact, on many tech policy issues it’s now difficult to find unbiased academics who have not received some Big Tech funding. Those who go against the grain find themselves in a rather precarious situation, as was recently shown by the fate of the Open Markets project at New America, an influential thinktank in Washington: its strong anti-monopoly stance appears to have angered New America’s chairman and major donor, Eric Schmidt, executive chairman of Alphabet. As a result, it was spun off from the thinktank.

Nonetheless, Big Tech’s political influence is not at the level of Wall Street or Big Oil. It’s hard to argue that Alphabet wields as much power over global technology policy as the likes of Goldman Sachs do over global financial and economic policy. For now, influential politicians – such as José Manuel Barroso, the former president of the European Commission – prefer to continue their careers at Goldman Sachs, not at Alphabet; it is also the former, not the latter, that fills vacant senior posts in Washington.

This will surely change. It’s obvious that the cheerful and utopian chatterboxes who make up TED talks no longer contribute much to boosting the legitimacy of the tech sector; fortunately, there’s a finite supply of bullshit on this planet. Big digital platforms will thus seek to acquire more policy leverage, following the playbook honed by the tobacco, oil and financial firms.

There are, however, two additional factors worth considering in order to understand where the current backlash against Big Tech might lead. First of all, short of a major privacy disaster, digital platforms will continue to be the world’s most admired and trusted brands – not least because they contrast so favourably with your average telecoms company or your average airline (say what you will of their rapaciousness, but tech firms don’t generally drag their customers off their flights).

And it is technology firms – American companies but also Chinese – that create the false impression that the global economy has recovered and everything is back to normal. Since January, the valuations of just four firms – Alphabet, Amazon, Facebook and Microsoft – have grown by an amount greater than the entire GDP of oil-rich Norway. Who would want to see this bubble burst? Nobody; in fact, those in power would rather see it grow some more.

The culture power of Silicon Valley can be gleaned from the simple fact that no sensible politician dares to go to Wall Street for photo ops; everyone goes to Palo Alto to unveil their latest pro-innovation policy. Emmanuel Macron wants to turn France into a startup, not a hedge fund. There’s no other narrative in town that makes centrist, neoliberal policies look palatable and inevitable at the same time; politicians, however angry they might sound about Silicon Valley’s monopoly power, do not really have an alternative project. It’s not just Macron: from Italy’s Matteo Renzi to Canada’s Justin Trudeau, all mainstream politicians who have claimed to offer a clever break with the past also offer an implicit pact with Big Tech – or, at least, its ideas – in the future.

Second, Silicon Valley, being the home of venture capital, is good at spotting global trends early on. Its cleverest minds had sensed the backlash brewing before the rest of us. They also made the right call in deciding that wonky memos and thinktank reports won’t quell our discontent, and that many other problems – from growing inequality to the general unease about globalisation – will eventually be blamed on an industry that did little to cause them.

Silicon Valley’s brightest minds realised they needed bold proposals – a guaranteed basic income, a tax on robots, experiments with fully privatised cities to be run by technology companies outside of government jurisdiction – that will sow doubt in the minds of those who might have otherwise opted for conventional anti-monopoly legislation. If technology firms can play a constructive role in funding our basic income, if Alphabet or Amazon can run Detroit or New York with the same efficiency that they run their platforms, if Microsoft can infer signs of cancer from our search queries: should we really be putting obstacles in their way?

In the boldness and vagueness of its plans to save capitalism, Silicon Valley might out-TED the TED talks. There are many reasons why such attempts won’t succeed in their grand mission even if they would make these firms a lot of money in the short term and help delay public anger by another decade. The main reason is simple: how could one possibly expect a bunch of rent-extracting enterprises with business models that are reminiscent of feudalism to resuscitate global capitalism and to establish a new New Deal that would constrain the greed of capitalists, many of whom also happen to be the investors behind these firms?

Data might seem infinite but there’s no reason to believe that the enormous profits made from it would simply smooth over the many contradictions of the current economic system. A self-proclaimed caretaker of global capitalism, Silicon Valley is much more likely to end up as its undertaker.

Tuesday, 19 May 2015

Abracadabra! Britain’s political elite has fooled us all again

Aditya Chakrabortty in The Guardian

Magicians call it misdirection: directing the attention of a crowd elsewhere so as to distract from the trick happening right in front of it. A bump on the shoulder, a blur of handwaving and – wham! – your wallet’s taken leave of your hip pocket.

Since the crash, British politics has been one epic act of misdirection. Lay off those bankers who shoved the country into penury! Just focus on stripping disabled people of their benefits. Never mind the millionaire bosses squeezing your pay! Spit instead at the minimum-wage migrant cleaners apparently making us poorer. So ingrained is the ritual that when a minister strides into view urging the need for “a grown-up debate”, we brace ourselves for another round of Blame the Victim. The only question is who gets sacrificed next: some ethnic minority, this family on low pay, that middle-aged dad who can’t get a job.

Here is how political misdirection works in real time. Yesterday, Unite’s Len McCluskey came under a barrage of criticism for suggesting that Labour live up to its name and support “ordinary working people”. Evil paymaster! Meanwhile, on the front page of this paper, digger firm JCB called on David Cameron to prepare to take Britain out of the EU – and this was just a company having its say.

I hold no brief for McCluskey – but he is the democratically elected head of a trade union simply seeking to influence the party part-funded by his members. Perhaps this comes as news to some on Fleet Street, but the debate over Labour’s future is not the chew-toy solely of newspaper columnists. Moreover, Unite’s donations to Her Majesty’s Opposition are a matter of easily checkable record. Not so the money poured into Tory coffers by JCB, either as a business or from its owners, the Bamford family. To learn that, we must rely upon forensic researchers such as Stuart Wilks-Heeg at Liverpool University. He calculated this morning that, between 2001-14, the Bamfords and JCB had together given the Conservatives at least £6.7m. One arm of JCB also donated £600,000 last year to Tory campaigns in key marginals, including the all-important battleground of Nuneaton.

So a company that funded David Cameron all the way into Downing Street, and whose chairman was recently made a lord, seeks to influence the government on one of the most fundamental issues in British politics, something that affects all of us – and this is business as usual. Yet a workers’ elected representative adding his voice to the din of an internal party argument somehow represents the biggest political landgrab since a bloke with a goatee popped in to the Winter Palace.

Expect more of this misdirection over the next few weeks. Labour has scheduled the entire summer for its leadership campaign, which could equal months of an entire party sounding like an indecisive satnav: Veer right! Keep left! Meanwhile, in just over a month, George Osborne will lay out an emergency budget to deal with the enormous £90bn deficit that he inherited from himself. Using the traditional lexicon of political hocus-pocus – “hard choices” – he will begin making some of the extra £12bn of welfare cuts the Tories pledged at the last election.

Every feat of misdirection is always intended to distract the audience from a sleight of hand. The same goes in politics – only here it’s aimed at taking our minds off the fact that all this jiggery-pokery is actually making us worse off. Let me show you what I mean, using figures calculated for the Guardian by academics at the Centre for Research on Socio-Cultural Change (Cresc), using official data. When Thatcher moved into No 10, 28% of all working age households took more from the state in cash benefits, in health and education and all the rest of it than they paid back in taxes. In other words, more than one in four employers in Britain were failing to pay their staff’s way.

More than three decades later, through Major and Blair and Brown and Cameron, that proportion has kept on rising. Now 38% of working-age households rely on taxpayers to pay their way. Think about all those tax credits for low-paid work, those exemptions for people earning too little even to be taxed. We have more people in work than ever before – and more households than ever before relying on the state to keep them afloat.

There’s nothing wrong with these people. These are the hard-working families politicians like talking about – the strivers, the squeezed middle, the alarm-clock Britain. But there’s a lot wrong with their employers – because they now rely on taxpayers to top up poverty pay, even while insisting on cuts in corporation tax and grants for investment. Come 8 July, it won’t be those businesses that the chancellor tells to change their ways – it’ll be the people they employ who will see more money taken out of their weekly budget by the cuts. Because the one thing we know about the next round of cuts is that they will hit the working poor all over again, like a hammer to the face.

This is what politics looks like in Britain nowadays, once the newspapers have their japes and the politicians leave the TV studios: it is about justifying an extractive business class that wants to lean on taxpayers to pay their way, even while lecturing the rest of us about welfare dependency. And it doesn’t change all that much whether the Tories or Labour are in Downing Street. The Cresc team looked at who reaped the rewards from growth over the past three decades. Under Thatcher and Major, the top 10% of all working-age households took 29p in every £1 of income growth. Under Blair and Brown, their share actually went up, to 30p in each £1. Cresc found that New Labour bumped up the share of the poorest economically active households from 0.5% to 1.5%. Taxes and benefits evened that up a bit – the same taxes and benefits that are now deemed unaffordable. So much for trickle down.

This is what all the misdirection has been about: taking our minds off the fact that Britain is a soft touch for businesses that want taxpayers to pay their way, and politicians who count on the middle classes to feel richer, not through their wage packets, but by their house prices, their no-frills flights, their luxury buys from Lidl. What a trick has been pulled on Britain by its political and business elite: never have so many people had their pockets picked at the same time.

Tuesday, 9 December 2014

Beware Russia’s links with Europe’s right

Moscow is handing cash to the Front National and others in order to exploit popular dissent against the European Union

It sounds like a chapter from a cheesy spy novel: former KGB agent, chucked out of Britain in the 80s, lends a large sum of money to a far-right European party. His goal? To undermine the European Union and consolidate ties between Moscow and the future possible leader of pro-Kremlin France.

In fact this is exactly what’s just happened. The founder of the Front National (FN), Jean-Marie Le Pen, borrowed €2m from a Cyprus-based company, Veronisa Holdings,owned by a flamboyant character and cold war operative called Yuri Kudimov.

Kudimov is a former KGB agent turned banker with close links to the Kremlin and the network of big money around it. Back in 1985 Kudimov was based in London. His cover story was that he was a journalist working for a Soviet newspaper; in 1985 the Thatcher government expelled him for alleged spying. (During the same period Vladimir Putin was a KGB officer in Dresden.)

In Paris, the FN confirmed last week that it had taken a whopping €9.4m (£7.4m) loan from the First Czech Russian bank in Moscow. This loan is logical enough. The FN’s leader, Marine Le Pen, makes no secret of her admiration for Putin; her party has links to senior Kremlin figures including Dmitry Rogozin, now Russia’s deputy prime minister, who in 2005 ran an anti-immigrant campaign under the slogan “Clean Up Moscow’s Trash”. Le Pen defended her decision to take the Kremlin money, complaining that she had been refused her access to capital: “What is scandalous here is that the French banks are not lending.” She also denied reports by the news website Mediapart, which broke the story, that the €9.4m was merely the first instalment of a bigger €40m loan.

The Russian money will fuel Marine Le Pen’s run for the French presidency in two years’ time. Nobody expects her to win, but the FN topped the polls in May’s European elections, winning an unprecedented 25% of the vote; Le Pen’s 25 new MEPs already form a pro-Russian bloc inside the European parliament.

In part, the Moscow loan can be understood as an act of minor and demonstrative revenge. It follows President François Hollande’s decision to postpone the delivery to Moscow of the first of two Mistral helicopter carriers, in a deal worth €1.2bn. His U-turn follows considerable western pressure, in the wake of Russia’s annexation of Crimea and its ongoing covert invasion of eastern Ukraine.

But there is also a more profound and sinister aspect to the Moscow cheque. Since at least 2009 Russia has actively cultivated links with the far right in eastern Europe. It has established ties with Hungary’s Jobbik, Slovakia’s far-right People’s party and Bulgaria’s nationalist, anti-EU Attack movement. Here, political elites have become increasingly sympathetic to pro-Putin views.

According to Political Capital, a Budapest-based research institute which first observed this trend, the Kremlin has recently been wooing the far-right in western Europe as well. In a report in March it argued that Russian influence in the affairs of the far right is now a “phenomenon seen all over Europe”. Moscow’s goal is to promote its economic and political interests – and in particular to ensure the EU remains heavily dependent on Russian gas.

In Soviet times the KGB used “active measures” to sponsor front organisations in the west including pro-Moscow communist parties. The Kremlin didn’t invent Europe’s far-right parties. But in an analogous way Moscow is now lending them support, political and financial, thereby boosting European neo-fascism.

In part this kinship is about ideology or, as Political Capital puts it, “post-communist neo-conservatism”. The European far right and the Kremlin are united by their hostility to the EU. Since becoming president for the third time in 2012, Putin has been busy promoting his vision for a rival Eurasian Union. This is an alternative political bloc meant to encompass now-independent Soviet republics, with Moscow rather than Brussels as the dominant pole.

The Kremlin has also discovered that the western political system is weak, permeable and susceptible to foreign cash. Putin has always believed that European politicians, like Russian ones, can be bought if the money is right. According to US diplomatic cables leaked in 2010, Silvio Berlusconi has benefited “personally and handsomely” from energy deals with Russia; the former German chancellor Gerhard Schröder, Putin’s greatest European ally, sits on the board of the Nord Steam Russian-German gas pipeline.

Far-right and rightwing British politicians, meanwhile, have also expressed their admiration for Russia’s ex-KGB president. In March Nigel Farage named Putin as the world leader he most admires, and praised the “brilliant” way “he handled the whole Syria thing”. In 2011 the BNP’s Nick Griffin went to Moscow to observe Russia’s Duma election. Afterwards he announced that “Russian elections are much fairer than Britain’s”. Last week Griffin tweeted praise for Russia Today, the Kremlin’s English-language TV propaganda news channel: “RT – For People Who Want the Truth”.

There are many ironies here. In his state of the nation address last Friday, Putin implicitly compared the west to Hitler, and said it was plotting Russia’s dismemberment and collapse. In March Putin defended his land-grab in Crimea by arguing he was rescuing the peninsula from Ukrainian “fascists”. A few weeks later a motley group of radical rightwing European populists turned up in Crimea to watch its hastily arranged “referendum”.

Tactically, Russia is exploiting the popular dissent against the EU – fuelled by both immigration and austerity. But as rightwing movements grow in influence across the continent, Europe must wake up to their insidious means of funding, or risk seeing its own institutions subverted.

Monday, 8 December 2014

Taming corporate power: the key political issue of our age

Big business and its lobbyists have taken control of our politics. But there is an alternative. In the first of a new series, here’s how we can take on the fat cats

Does this sometimes feel like a country under enemy occupation? Do you wonder why the demands of so much of the electorate seldom translate into policy? Why parties of the left seem incapable of offering effective opposition to market fundamentalism, let alone proposing coherent alternatives? Do you wonder why those who want a kind and decent and just world, in which both human beings and other living creatures are protected, so often appear to be opposed by the entire political establishment?

If so, you have encountered corporate power – the corrupting influence that prevents parties from connecting with the public, distorts spending and tax decisions, and limits the scope of democracy. It helps explain the otherwise inexplicable: the creeping privatisation of health and education, hated by the vast majority of voters; the private finance initiative, which has left public services with unpayable debts; the replacement of the civil service with companies distinguished only by incompetence; the failure to re-regulate the banks and collect tax; the war on the natural world; the scrapping of the safeguards that protect us from exploitation; above all, the severe limitation of political choice in a nation crying out for alternatives.

There are many ways in which it operates, but perhaps the most obvious is through our unreformed political funding system, which permits big business and multimillionaires in effect to buy political parties. Once a party is obliged to them, it needs little reminder of where its interests lie. Fear and favour rule.

And if they fail? Well, there are other means. Before the last election, a radical firebrand said this about the lobbying industry: “It is the next big scandal waiting to happen ... an issue that exposes the far-too-cosy relationship between politics, government, business and money ... secret corporate lobbying, like the expenses scandal, goes to the heart of why people are so fed up with politics.” That, of course, was David Cameron, and he’s since ensured that the scandal continues. His Lobbying Act restricts the activities of charities and trade unions but imposes no meaningful restraint on corporations.

Ministers and civil servants know that if they keep faith with corporations in office they will be assured of lucrative directorships in retirement. As head of HMRC, the UK government’s tax-collection agency, Dave Hartnett oversaw some highly controversial deals with companies such as Vodafone and Goldman Sachs, apparently excusing them from much of the tax they seemed to owe. He now works for Deloitte, which advises companies such as Vodafone on their tax affairs. As head of HMRC he met one Deloitte partner 48 times.

Corporations have also been empowered by the globalisation of decision-making. As powers, but not representation, shift to the global level, multinational business and its lobbyists fill the political gap. When everything has been globalised except our consent, we are vulnerable to decisions made outside the democratic sphere.

The key political question of our age, by which you can judge the intent of all political parties, is what to do about corporate power. This is the question, perennially neglected within both politics and the media, that this week’s series of articles will attempt to address. I think there are some obvious first steps.

A sound political funding system would be based on membership fees. Each party would be able to charge the same fixed fee for annual membership (perhaps £30 or £50). It would receive matching funding from the state as a multiple of its membership receipts. No other sources of income would be permitted. As well as getting the dirty money out of politics, this would force political parties to reconnect with the people, to raise their membership. It will cost less than the money wasted on corporate welfare every day.

All lobbying should be transparent. Any meeting between those who are paid to influence opinion (this could include political commentators like me) and ministers, advisers or civil servants should be recorded, and the transcript made publicly available. The corporate lobby groups that pose as thinktanks should be obliged to reveal who funds them before appearing on the broadcast media; and if the identity of one of their funders is relevant to the issue they are discussing, it should be mentioned on air.

Any company supplying public services would be subject to freedom of information laws (with an exception for matters deemed commercially confidential by the information commissioner). Gagging contracts would be made illegal, in the private as well as the public sector (with the same exemption for commercial confidentiality). Ministers and top officials should be forbidden from taking jobs in the sectors they were charged with regulating.

But we should also think of digging deeper. Is it not time we reviewed the remarkable gift we have granted to companies in the form of limited liability? It socialises the risks that would otherwise be carried by a company’s owners and directors, exempting them from the costs of the debts they incur or the disasters they cause, and encouraging them to engage in the kind of reckless behaviour that caused the financial crisis. Should the wealthy authors of the crisis, such as RBS chief Fred Goodwin or Northern Rock’s Matt Ridley, not have incurred a financial penalty of their own?

We should look at how we might democratise the undemocratic institutions of global governance, as I suggested in my book The Age of Consent. This could involve dismantling the World Bank and the IMF, which are governed without a semblance of democracy, and cause more crises than they solve, and replacing them with a body rather like the international clearing union designed by John Maynard Keynes in the 1940s – whose purpose was to prevent excessive trade surpluses and deficits from forming, and therefore international debt from accumulating.

Instead of treaties brokered in opaque meetings (of the kind now working towards atransatlantic trade and investment partnership) between diplomats and transnational capital – which threaten democracy, the sovereignty of parliaments and the principle of equality before the law – we should demand a set of global fair trade rules. Multinational companies should lose their licence to trade if they break them.

Above all, perhaps, we need a directly elected world parliament, whose purpose would be to hold other global bodies to account. In other words, instead of only responding to an agenda set by corporations, we must propose an agenda of our own.

This is not only about politicians, it is also about us. Corporate power has shut down our imagination, persuading us that there is no alternative to market fundamentalism, and that “market” is a reasonable description of a state-endorsed corporate oligarchy.

We have been persuaded that we have power only as consumers, that citizenship is an anachronism, that changing the world is either impossible or best effected by buying a different brand of biscuits. Corporate power now lives within us. Confronting it means shaking off the manacles it has imposed on our minds.

Saturday, 14 June 2014

When Are Foreign Funds Okay?

by Nivedita Menon in Kafila

The Intelligence Bureau has, as we know prepared a document, updating it from the time of the UPA regime (which had reportedly started the dossier) indicating large scale foreign funding for subversive anti-development activities. Such as claiming that you have a greater right to your own lands and to your livelihood than monstrous profit-making private companies. Or raising ecological arguments that might stand in the way of the profits to be made by private corporations and the corrupt state elite, from mining, big dams, multi-lane highways and so on.

The IB report, signed by IB joint director Safi A Rizvi — alleges that the “areas of action” of the foreign-funded NGOs include anti-nuclear, anti-coal and anti-Genetically Modified Organisms protests. Apart from stalling mega industrial projects including those floated by POSCO and Vedanta, these NGOs have also been working to the detriment of mining, dam and oil drilling projects in north-eastern India, it adds.

Imagine—working against the interests of POSCO and Vedanta! Is there no end to the depraved anti-nationalism of these NGOs!

The average observer of Indian politics—being like me, not as sharp as the IB—might be a little befuddled by this apparently anachronistic allergy of two successive governments and its intelligence gathering organization, towards foreign funding, in an era in which the slightest slowing down of the pace of handing over the nation’s resources to multi-national corporations, is termed as “policy paralysis”, and attacked as detrimental to the health of the mythical “Sensex”. Older readers might remember that the inspiring slogan of the legendary Jaspal Bhatti’s Feel Good party was Sensex ooncha rahe hamara.

This post is just to help you figure out then, when it is Okay to applaud foreign funding and when it is not—because otherwise you might post something on your FaceBook page that attacks foreign funding when it is actually Okay—and then how stupid and anti-national you’ll look. Apart from being arrested and hauled off to jail, a few other “innocent” people might be killed, for as we know, if you did post something “objectionable” to the Hindu Right/India, you’re not innocent and may be legitimately killed. The street gangs of the Hindu Right have been in readiness for this moment when Their Man is PM for some years now. They also know that Their Man may not publicly defend them at all times—depends on whether they carry out their work in a non-BJP state or not. And whether state assembly elections are coming up there or not. That is called being Drigdarshi. Far-sighted.

So in Maharashtra, Mohsin’s killing was described—in an apparent paradox—by the BJP ‘s central government Home Ministry as “communal” and by the state’s Congress government as merely “a law and order problem”. But in fact, not a paradox at all. The BJP is always keen to point out communal violence in states in which it is not in power. And the Congress plays the secular/communal card with the same unprincipled cynicism.

But I digress.

So—When are Foreign Funds Okay?

a) Foreign Funds are Okay if you are BJP.

The Delhi High Court indicted both Congress and BJP in March 2014 for accepting foreign funds from Vedanta subsidiaries in violation of provisions of Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act. (Vedanta clearly believes in covering all its bases—after all, who knows who will come to power).

BJP and Congress in their defence had argued that Vedanta is owned by an Indian citizen, Aggarwal, and its subsidiaries are incorporated here, therefore they are not foreign sources.

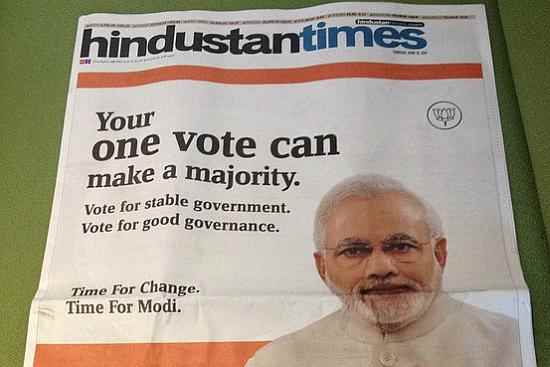

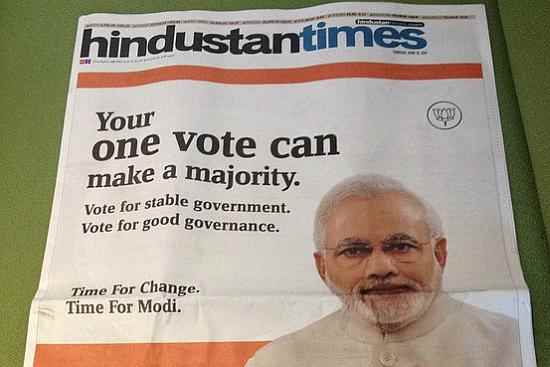

That’s the kind of fine distinction you must learn to make. For instance, there is no cap on parties’ expenditure during elections, only on individual candidates’ spending. Thus, Narendra Modi’s face on the front page of every newspaper and on huge hoardings all over the city did not get counted towards his poll expenditure. A Hindustan Times premium front page advertisement costs Rs 3950 PER SQUARE CENTIMETER.

How many advertisements like this one did you see? In how many newspapers? Over how many days? Where did the money come from?

How many advertisements like this one did you see? In how many newspapers? Over how many days? Where did the money come from?

We don’t know.

But—Remember—It does NOT matter, because Foreign Funds are Okay if you’re the BJP.