Parts of Rahul Gandhi's above speech expunged by Speaker Om Birla

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label violence. Show all posts

Showing posts with label violence. Show all posts

Monday, 1 July 2024

Friday, 9 February 2024

Wednesday, 15 March 2023

Friday, 30 September 2022

Friday, 25 March 2022

Confidence Tricks: Pakistan

Abdul Moiz Jaferi in The Dawn

By 2050, Pakistan will become the third most populous country in the world with 380 million mostly poor people. The Pakistanis working towards making those future millions a reality, are doing so today fuelled by largely imported foodstuff. Before you start screaming at the fromagers and the chocolatiers, they are not really to blame. Our daal is from abroad, and so is the oil it is cooked in. Our broiler chicken is fed foreign produce and even our naan dough is supplemented with imports.

We are already a food-insecure country, even though agriculture is supposed to be our backbone. Our once formidable cotton produce struggles to keep up with the region. Without investment in seed quality and technology, our cotton crop is now only fit to make coarse materials. Farmers have no incentive from the state to support essential crops, so they plant fields upon fields of water-hungry sugarcane, producing a crop which goes into a regressively controlled and speculative sugar industry and comes out as per the whims of billionaires with private planes.

Pakistan earns about eight thousand billion rupees a year in tax and non-tax revenue. Let’s try and approximate this as a single naan. About half of that naan is put together with sales tax and customs duties — indirect and retrogressive taxation which extracts without discriminating between the poor buyer and the rich. An eighth of the naan is income tax, which is paid in large part by a million-odd poor souls caught in the net of ‘deductions at source’, who are either too weak or too caught in the net to get away with tax theft. These poor souls do silly things, such as subscribe to English-language print dailies like this one, whilst their trader neighbours rely on WhatsApp videos for their news stories, drive flashier vehicles, and write odes to their fictional poverty for the taxman and get away with it. A quarter of the naan is non-tax revenue; a final eighth is put on the table by federal excise duties and miscellaneous levies such as those on petroleum.

When it comes to spending this money, Pakistan gives just under half the naan away to its provinces, who have many more responsibilities after the 18th Amendment but have not expanded their own revenue portfolios, nor devolved power or funding to local government. We then give away three-eighths to debt servicing. Those adept at math will guess that we have about an eighth left. Most of that goes to the military. We then borrow some more to run the actual government and pay pensions.

From the first day of work, we are in fresh debt, eating borrowed naan. Our economy is propped up by the sustenance sent home by unskilled labour, who toil to make foreign deserts green in conditions of modern-day slavery.

Countries break from such fatal cycles through improvement in their people — education and inclusion. Our basic public education system has been reduced to the worst possible state while our higher education system produces unnecessary degrees instead of focusing on skill-based diplomas. Our doctoral circuit is best known for being an elaborate diploma mill, where dummy publications print you onwards to hollow PhD glory.

If you consider the threat of violent force to be a commodity, it is our major produce and international bargaining chip. We bring to the table our possible nuisance value and take back whatever the world is willing to give us if we promise to keep it in check. At the head of the institutions which regulate our use of force are people who realise that their own powerful hand spins the roulette wheel which determines many fates, including their own.

Meanwhile, the pinnacle of the established order in our country enjoys millions of dollars’ worth of retirement packages and is bestowed with state land as service gifts and depreciated duty-free luxury vehicles as buy-offs. Golf clubs are carved out of mountains for their subsidised leisure; lakeside vistas become their sailing clubs.

Our country’s largest corporate players are owned and run by the military. I would say our country’s largest political player is also the military, but then this paper might not print it and, as penance, I might have to go to a seminar at Lums, where, a satirical publication noted, a management scientist recently turned up to speak for the whole day.

When you throw a no-confidence motion against a prime minister into this mix, it seems minor in scale. A sleight of hand compared to the larger circus that is the running of our country. When you factor in that the process through which he is being removed is itself riddled with the same interference from unelected quarters which had drawn condemnation from across the aisle when he was first brought in, the farce is highlighted further.

The opposition, previously being unable to remove the Sadiq Sanjrani pony from the merry-go-round that is our political arena, has now realised where the ticket booth is. Everyone is now jumping the queue to exchange their lofty slogans for a ticket on the ride, while the ringmaster promises larger and larger horses as long as the circus stays in town.

If I was part of the management science team which ran Pakistan’s circus, I would encourage my colleagues to wake up and smell the urgency in the air: the poverty which encircles the circus’s manicured boundaries. It is not long before the only solution to all evils will once again present itself as a gross permutation of religion and violence. Unlike last time, when we went after the Russians with it whilst taking American money (which ended up in Swiss banks), this time it threatens to burn without direction or order, and without a care for how much of the forest will remain when the flames are finally doused.

By 2050, Pakistan will become the third most populous country in the world with 380 million mostly poor people. The Pakistanis working towards making those future millions a reality, are doing so today fuelled by largely imported foodstuff. Before you start screaming at the fromagers and the chocolatiers, they are not really to blame. Our daal is from abroad, and so is the oil it is cooked in. Our broiler chicken is fed foreign produce and even our naan dough is supplemented with imports.

We are already a food-insecure country, even though agriculture is supposed to be our backbone. Our once formidable cotton produce struggles to keep up with the region. Without investment in seed quality and technology, our cotton crop is now only fit to make coarse materials. Farmers have no incentive from the state to support essential crops, so they plant fields upon fields of water-hungry sugarcane, producing a crop which goes into a regressively controlled and speculative sugar industry and comes out as per the whims of billionaires with private planes.

Pakistan earns about eight thousand billion rupees a year in tax and non-tax revenue. Let’s try and approximate this as a single naan. About half of that naan is put together with sales tax and customs duties — indirect and retrogressive taxation which extracts without discriminating between the poor buyer and the rich. An eighth of the naan is income tax, which is paid in large part by a million-odd poor souls caught in the net of ‘deductions at source’, who are either too weak or too caught in the net to get away with tax theft. These poor souls do silly things, such as subscribe to English-language print dailies like this one, whilst their trader neighbours rely on WhatsApp videos for their news stories, drive flashier vehicles, and write odes to their fictional poverty for the taxman and get away with it. A quarter of the naan is non-tax revenue; a final eighth is put on the table by federal excise duties and miscellaneous levies such as those on petroleum.

When it comes to spending this money, Pakistan gives just under half the naan away to its provinces, who have many more responsibilities after the 18th Amendment but have not expanded their own revenue portfolios, nor devolved power or funding to local government. We then give away three-eighths to debt servicing. Those adept at math will guess that we have about an eighth left. Most of that goes to the military. We then borrow some more to run the actual government and pay pensions.

From the first day of work, we are in fresh debt, eating borrowed naan. Our economy is propped up by the sustenance sent home by unskilled labour, who toil to make foreign deserts green in conditions of modern-day slavery.

Countries break from such fatal cycles through improvement in their people — education and inclusion. Our basic public education system has been reduced to the worst possible state while our higher education system produces unnecessary degrees instead of focusing on skill-based diplomas. Our doctoral circuit is best known for being an elaborate diploma mill, where dummy publications print you onwards to hollow PhD glory.

If you consider the threat of violent force to be a commodity, it is our major produce and international bargaining chip. We bring to the table our possible nuisance value and take back whatever the world is willing to give us if we promise to keep it in check. At the head of the institutions which regulate our use of force are people who realise that their own powerful hand spins the roulette wheel which determines many fates, including their own.

Meanwhile, the pinnacle of the established order in our country enjoys millions of dollars’ worth of retirement packages and is bestowed with state land as service gifts and depreciated duty-free luxury vehicles as buy-offs. Golf clubs are carved out of mountains for their subsidised leisure; lakeside vistas become their sailing clubs.

Our country’s largest corporate players are owned and run by the military. I would say our country’s largest political player is also the military, but then this paper might not print it and, as penance, I might have to go to a seminar at Lums, where, a satirical publication noted, a management scientist recently turned up to speak for the whole day.

When you throw a no-confidence motion against a prime minister into this mix, it seems minor in scale. A sleight of hand compared to the larger circus that is the running of our country. When you factor in that the process through which he is being removed is itself riddled with the same interference from unelected quarters which had drawn condemnation from across the aisle when he was first brought in, the farce is highlighted further.

The opposition, previously being unable to remove the Sadiq Sanjrani pony from the merry-go-round that is our political arena, has now realised where the ticket booth is. Everyone is now jumping the queue to exchange their lofty slogans for a ticket on the ride, while the ringmaster promises larger and larger horses as long as the circus stays in town.

If I was part of the management science team which ran Pakistan’s circus, I would encourage my colleagues to wake up and smell the urgency in the air: the poverty which encircles the circus’s manicured boundaries. It is not long before the only solution to all evils will once again present itself as a gross permutation of religion and violence. Unlike last time, when we went after the Russians with it whilst taking American money (which ended up in Swiss banks), this time it threatens to burn without direction or order, and without a care for how much of the forest will remain when the flames are finally doused.

Monday, 13 September 2021

Friday, 9 July 2021

Thursday, 28 January 2021

Saturday, 9 January 2021

Sunday, 13 September 2020

Wednesday, 4 December 2019

Monday, 12 August 2019

Do and be damned; don’t and still be damned

Girish Menon

It’s been a week since the BJP government abrogated Article 370 and included Jammu and Kashmir as an integral part of India. Most of the reaction to this move has been positive within the provinces of Jammu and Ladakh. It is difficult to gauge the views of the population in the Muslim majority Kashmir valley because of the news blackout. I’d guess there should be a significant number of people who may be upset by this decision. In mainland India, the move has been welcomed by most of the people and a majority of MPs in both houses of the Indian Parliament.

Outside India, Pakistan politicians including their selected Prime Minister have been venting their spleen on this surprise move by India. Opinion in the rest of the world has been muted much to the chagrin of Pakistan. It is rumoured that the US President was forewarned by India of its plans.

So what next for the protesting Kashmiris? The Kashmiris living in the valley could be divided into the ruling elites, those families directly affected by the violence since 1989, and other citizens living in the region.

As far as the ruling elites are concerned, they must admit that it is their actions since the 1950s that has enabled the Indian government to get the support of the rest of India for such a move.

As far as Kashmir residents who have lost their family members in the intermittent 70 year old war with Pakistan there is no likelihood of an immediate peace in the region. Pakistan’s proxies, along with some local politicians will make it difficult for the Modi government to boast that they have solved this perennial problem with a piece of legislation. This means that in the short term there could be more deaths in the valley.

Those valley residents who have only been indirectly affected by the war so far, in the short term some of them may be unlucky to get caught up in the fire exchanged by the warring forces. I hope that their bad luck will run out soon and they will be able to experience a ‘normal’ way of life soon.

The Indian government appears intent on a hard stance on law and order matters while being liberal on incentivising industry to start productive activity and employment in these parts. Both parts of this strategy needs to succeed to convince the Kashmiris that their interests are better served with India. This could lead to the chants of ‘azaadi’ (freedom from both India and Pakistan) to die down.

The current Indian government has five years to get this brave decision right. If the situation deteriorates then they further jeopardise their dreams of continuous power for the next decade and beyond. Already the weakness in their handling of the economy is manifesting itself in the Hindu rate of growth with deleterious consequences for employment. If they fail on Kashmir as well, there will be a rising number of citizens who will soon call Modi’s Article 370 decision the second time when he has been foolhardy.

Just wait and watch.

Friday, 30 November 2018

Brace yourself, Britain. Brexit is about to teach you what a crisis actually is

Seven decades of prosperity have lulled the UK into thinking we’re special – that disasters only happen to other people writes David Bennun in The Guardian

Britain is not Kenya. It is, in the ordinary run of things, much better protected against such convulsions than a country such as Kenya. But do away with the ordinary run of things, and any place in the world can suffer as Kenya did then. You don’t have to look too far back at European history to see it, nor do you have to look away from home. The British people I know who most swiftly grasped and vividly understood the implications of present events as they began to unfold are Northern Irish. There’s a reason for that.

Democratic institutions, the rule of law, civic infrastructure, a culture of local and national governance in which corruption, while ever present, is exceptional rather than institutional: these things, flawed as they may be and ever improvable as they are, take generations, even centuries to build. But once they topple, they can topple at terrifying speed and with terrifying effect. Britain has forgotten what that’s like.

All the talk about the “Blitz spirit” comes from people who have never known what it is to truly fear everything crashing down around you. In liberal democracies enthusiasm for a revolution usually comes from people who have known nothing but the safety and freedom of the “system” – which is to say the imperfect protective structure – that they abhor. Talk to anyone who has experienced the glories of such upheaval and they are generally not quite so keen on it.

To be, politically speaking, a grownup is something to be sneered at these days. It means you’re lacking in imagination, in boldness of vision, in belief in a better country or a better world. That’s a view held invariably by people who would, without grownups running things, have been lucky to survive long enough to articulate it. Similarly, a contempt for expertise is inevitably expressed by those who, without experts contributing to society as they do, would be lucky to have a voice to speak with, let alone a platform on which to use it. Expertise, like democracy, is far from infallible; each, however, is always preferable to the alternative.

When the grownups fail, as they periodically do, and badly, what you need is better grownups. Awful things have happened, and do happen, in this country, chiefly as a result of bad policy and worse enactment. We don’t need to have homelessness, dependency on food banks or deprived areas ruled by criminals and bullies. We can afford to act against these evils, but we let them happen all the same. That shames us. Hand the keys and the controls over to eternal teenagers – populists of either stripe – and what you’ll get is a situation where that choice is gone.

We’re not special. If, in a deluded fit of national self-harm that ever more resembles the drift into war in 1914, we allow ourselves to wreck the complicated machinery that underpins our everyday lives without us ever having to think much about it, nobody will be coming to rescue us. Cassandra, as Cassandras are always ready to remind you, was right.

Keeping calm in Chipping Norton, Oxfordshire: ‘The idea that we’re protected, we’re exceptional, is not articulated … but it’s there.’ Photograph: JOHN ROBERTSON

Most British people don’t have the first inkling of what a crisis is. They think it’s a political thing. “Government in crisis”, and so on. Whatever happens at the top, life will go on as ever. There will be food in the shops, medical supplies in the hospitals, water in the taps and order on the streets (as much as there usually is). Anyone who warns you otherwise is a catastrophist, a drama queen, a scaremonger, a Cassandra.

That’s what a seven-decade period of general peace and collective prosperity does for you. It makes you think it’s normal, rather than a hard-won, fragile rarity in history. It makes most people complacent, and turns a small but unfortunately influential number into the kind of adolescent romantics who think you can smash up everything in the house and stick two fingers up to Mummy and Daddy because, no matter what you do, they will always be there to make it right in the end. Mummy and Daddy won’t let anything too bad happen to us.

The idea that we’re protected, we’re exceptional, is not articulated or usually even conscious. But it’s there. That this is who we are. Disaster – mass, national disaster – happens to other people, in other places.

But there is no such rule. No such guarantee. Mummy and Daddy won’t always come to bail us out. And if you’ve ever lived in one of those other places, chances are you will have seen how quickly what you thought was an orderly society can disintegrate under pressure. If you’ve never known gunfire and mobs on the streets, or empty taps and empty shelves, or power that’s off more than it’s on, or morgues full of the victims of racial, political or tribal violence, you don’t have a clue how easily that can happen.

I experienced all these things when I was growing up in Kenya. Some were routine; the more severe, mercifully less so. Branded on my memory from an attempted coup d’état in 1982 is the sound of automatic rifle fire along the road; the crowds surging like waves; confusion and misinformation crackling from the radio; most of all, hearing the account of my late father, a doctor, of the aftermath of what I can best describe as a pogrom, unleashed by the breakdown of order, against the Asian people of Nairobi, his hospital full of the dead and grievously wounded people, many of them children no older than I was.

All the talk of “Blitz spirit” comes from people who have never known what it is to truly fear everything crashing down

Most British people don’t have the first inkling of what a crisis is. They think it’s a political thing. “Government in crisis”, and so on. Whatever happens at the top, life will go on as ever. There will be food in the shops, medical supplies in the hospitals, water in the taps and order on the streets (as much as there usually is). Anyone who warns you otherwise is a catastrophist, a drama queen, a scaremonger, a Cassandra.

That’s what a seven-decade period of general peace and collective prosperity does for you. It makes you think it’s normal, rather than a hard-won, fragile rarity in history. It makes most people complacent, and turns a small but unfortunately influential number into the kind of adolescent romantics who think you can smash up everything in the house and stick two fingers up to Mummy and Daddy because, no matter what you do, they will always be there to make it right in the end. Mummy and Daddy won’t let anything too bad happen to us.

The idea that we’re protected, we’re exceptional, is not articulated or usually even conscious. But it’s there. That this is who we are. Disaster – mass, national disaster – happens to other people, in other places.

But there is no such rule. No such guarantee. Mummy and Daddy won’t always come to bail us out. And if you’ve ever lived in one of those other places, chances are you will have seen how quickly what you thought was an orderly society can disintegrate under pressure. If you’ve never known gunfire and mobs on the streets, or empty taps and empty shelves, or power that’s off more than it’s on, or morgues full of the victims of racial, political or tribal violence, you don’t have a clue how easily that can happen.

I experienced all these things when I was growing up in Kenya. Some were routine; the more severe, mercifully less so. Branded on my memory from an attempted coup d’état in 1982 is the sound of automatic rifle fire along the road; the crowds surging like waves; confusion and misinformation crackling from the radio; most of all, hearing the account of my late father, a doctor, of the aftermath of what I can best describe as a pogrom, unleashed by the breakdown of order, against the Asian people of Nairobi, his hospital full of the dead and grievously wounded people, many of them children no older than I was.

All the talk of “Blitz spirit” comes from people who have never known what it is to truly fear everything crashing down

Britain is not Kenya. It is, in the ordinary run of things, much better protected against such convulsions than a country such as Kenya. But do away with the ordinary run of things, and any place in the world can suffer as Kenya did then. You don’t have to look too far back at European history to see it, nor do you have to look away from home. The British people I know who most swiftly grasped and vividly understood the implications of present events as they began to unfold are Northern Irish. There’s a reason for that.

Democratic institutions, the rule of law, civic infrastructure, a culture of local and national governance in which corruption, while ever present, is exceptional rather than institutional: these things, flawed as they may be and ever improvable as they are, take generations, even centuries to build. But once they topple, they can topple at terrifying speed and with terrifying effect. Britain has forgotten what that’s like.

All the talk about the “Blitz spirit” comes from people who have never known what it is to truly fear everything crashing down around you. In liberal democracies enthusiasm for a revolution usually comes from people who have known nothing but the safety and freedom of the “system” – which is to say the imperfect protective structure – that they abhor. Talk to anyone who has experienced the glories of such upheaval and they are generally not quite so keen on it.

To be, politically speaking, a grownup is something to be sneered at these days. It means you’re lacking in imagination, in boldness of vision, in belief in a better country or a better world. That’s a view held invariably by people who would, without grownups running things, have been lucky to survive long enough to articulate it. Similarly, a contempt for expertise is inevitably expressed by those who, without experts contributing to society as they do, would be lucky to have a voice to speak with, let alone a platform on which to use it. Expertise, like democracy, is far from infallible; each, however, is always preferable to the alternative.

When the grownups fail, as they periodically do, and badly, what you need is better grownups. Awful things have happened, and do happen, in this country, chiefly as a result of bad policy and worse enactment. We don’t need to have homelessness, dependency on food banks or deprived areas ruled by criminals and bullies. We can afford to act against these evils, but we let them happen all the same. That shames us. Hand the keys and the controls over to eternal teenagers – populists of either stripe – and what you’ll get is a situation where that choice is gone.

We’re not special. If, in a deluded fit of national self-harm that ever more resembles the drift into war in 1914, we allow ourselves to wreck the complicated machinery that underpins our everyday lives without us ever having to think much about it, nobody will be coming to rescue us. Cassandra, as Cassandras are always ready to remind you, was right.

Wednesday, 4 October 2017

On Ben Stokes - Do sportsmen have a responsibility to the sport?

Suresh Menon in The Hindu

One of the more amusing sights in cricket recently has been that of England trying desperately to work out a formula to simultaneously discipline Ben Stokes and retain him for the Ashes series. To be fair, such contortion is not unique. India once toured the West Indies with Navjot Singh Sidhu just after the player had been involved in a road rage case that led to a death.

Both times, the argument was one we hear politicians make all the time: Let the law takes its course. It is an abdication of responsibility by cricket boards fully aware of the obligation to uphold the image of the sport.

Cricketers, especially those who are talented, and therefore have been indulged, tend to enjoy what George Orwell has called the “benefit of the clergy”. Their star value is often a buffer against the kind of response others might have received. Given that the team leaves for Australia at the end of this month, it is unlikely that Stokes will tour anyway, yet the ECB’s reaction has been strange.

Neither Stokes nor Alex Hales, his partner at the brawl in Bristol which saw Stokes deliver what the police call ABH (Actual Bodily Harm), was dropped immediately from the squad. This is a pointer to the way cricket boards think.

An enquiry by the England and Wales Cricket Board (ECB) would not have taken more than a few hours. Given the cctv footage, the players’ own versions, and the testimony of the victims, it is unlikely that there could be any ambiguity about what happened. Yet the ECB has chosen to bring in its independent Cricket Discipline Commission only after the police have completed their inquiries.

Top sportsmen tend to be national heroes, unlike, say, top chartered accountants or geography teachers, and they have a responsibility to ensure they do not bring the sport into disrepute. It is a tough call, and not everybody agrees that your best all rounder should also be your most ideally-behaved human being. But that is the way it is. After all, sport is an artificial construct; rules around it might seem to be unrealistic too.

Stokes brought “the game into disrepute” — the reason Ian Botham and Andrew Flintoff were banned in the past — and he should not be in the team. The ECB’s response cannot be anything other than a ban. Yet, it is pussy-footing around the problem in the hope that there is a miracle. Perhaps the victims will not press charges. Perhaps the police might decide that the cctv images are inconclusive.

Clearly player behaviour is not the issue here. There are two other considerations. One was articulated by former Aussie captain Ian Chappell: Without Stokes, England stood no chance in the Ashes. The other, of equal if not greater concern to the ECB, is the impact of Stokes’s absence on sponsorship and advertising. Already the brewers Greene King has said it is withdrawing an advertisement featuring England players.

Scratch the surface on most moral issues, and you will hit the financial reasons that underlie them.

Stokes, it has been calculated, could lose up to two million pounds in endorsements, for “bringing the product into disrepute”, as written into the contracts. It will be interesting to see how the IPL deals with this — Stokes is the highest-paid foreign player in the tournament.

And yet — here is another sporting irony — there is the question of aggression itself. Stokes (like Botham and Flintoff and a host of others) accomplishes what he does on the field partly because of his fierce competitive nature and raw aggression.

Just as some players are intensely selfish, their selfishness being a reason for their success and therefore their team’s success, some players bring to the table sheer aggression.

Mike Atherton has suggested that Stokes should learn from Ricky Ponting who was constantly getting into trouble in bars early in his career. Ponting learnt to channelise that aggression and finished his career as one of the Aussie greats. A more recent example is David Warner, who paid for punching Joe Root in a bar some years ago, but seems to have settled down as both batsman and person.

Stokes will be missed at the Ashes. He has reduced England’s chances, even if Moeen Ali for one thinks that might not be the case.

Still, Stokes is only 26 and has many years to go. It is not too late to work on diverting all that aggression creatively. Doubtless he has been told this every time he has got into trouble. He is a rare talent, yet it would be a travesty if it all ended with a rap on the knuckles. England must live — however temporarily —without him.

One of the more amusing sights in cricket recently has been that of England trying desperately to work out a formula to simultaneously discipline Ben Stokes and retain him for the Ashes series. To be fair, such contortion is not unique. India once toured the West Indies with Navjot Singh Sidhu just after the player had been involved in a road rage case that led to a death.

Both times, the argument was one we hear politicians make all the time: Let the law takes its course. It is an abdication of responsibility by cricket boards fully aware of the obligation to uphold the image of the sport.

Cricketers, especially those who are talented, and therefore have been indulged, tend to enjoy what George Orwell has called the “benefit of the clergy”. Their star value is often a buffer against the kind of response others might have received. Given that the team leaves for Australia at the end of this month, it is unlikely that Stokes will tour anyway, yet the ECB’s reaction has been strange.

Neither Stokes nor Alex Hales, his partner at the brawl in Bristol which saw Stokes deliver what the police call ABH (Actual Bodily Harm), was dropped immediately from the squad. This is a pointer to the way cricket boards think.

An enquiry by the England and Wales Cricket Board (ECB) would not have taken more than a few hours. Given the cctv footage, the players’ own versions, and the testimony of the victims, it is unlikely that there could be any ambiguity about what happened. Yet the ECB has chosen to bring in its independent Cricket Discipline Commission only after the police have completed their inquiries.

Top sportsmen tend to be national heroes, unlike, say, top chartered accountants or geography teachers, and they have a responsibility to ensure they do not bring the sport into disrepute. It is a tough call, and not everybody agrees that your best all rounder should also be your most ideally-behaved human being. But that is the way it is. After all, sport is an artificial construct; rules around it might seem to be unrealistic too.

Stokes brought “the game into disrepute” — the reason Ian Botham and Andrew Flintoff were banned in the past — and he should not be in the team. The ECB’s response cannot be anything other than a ban. Yet, it is pussy-footing around the problem in the hope that there is a miracle. Perhaps the victims will not press charges. Perhaps the police might decide that the cctv images are inconclusive.

Clearly player behaviour is not the issue here. There are two other considerations. One was articulated by former Aussie captain Ian Chappell: Without Stokes, England stood no chance in the Ashes. The other, of equal if not greater concern to the ECB, is the impact of Stokes’s absence on sponsorship and advertising. Already the brewers Greene King has said it is withdrawing an advertisement featuring England players.

Scratch the surface on most moral issues, and you will hit the financial reasons that underlie them.

Stokes, it has been calculated, could lose up to two million pounds in endorsements, for “bringing the product into disrepute”, as written into the contracts. It will be interesting to see how the IPL deals with this — Stokes is the highest-paid foreign player in the tournament.

And yet — here is another sporting irony — there is the question of aggression itself. Stokes (like Botham and Flintoff and a host of others) accomplishes what he does on the field partly because of his fierce competitive nature and raw aggression.

Just as some players are intensely selfish, their selfishness being a reason for their success and therefore their team’s success, some players bring to the table sheer aggression.

Mike Atherton has suggested that Stokes should learn from Ricky Ponting who was constantly getting into trouble in bars early in his career. Ponting learnt to channelise that aggression and finished his career as one of the Aussie greats. A more recent example is David Warner, who paid for punching Joe Root in a bar some years ago, but seems to have settled down as both batsman and person.

Stokes will be missed at the Ashes. He has reduced England’s chances, even if Moeen Ali for one thinks that might not be the case.

Still, Stokes is only 26 and has many years to go. It is not too late to work on diverting all that aggression creatively. Doubtless he has been told this every time he has got into trouble. He is a rare talent, yet it would be a travesty if it all ended with a rap on the knuckles. England must live — however temporarily —without him.

Monday, 3 April 2017

Sky-gods and scapegoats: From Genesis to 9/11 to Khalid Masood, how righteous blame of 'the other' shapes human history

Andy Martin in The Independent

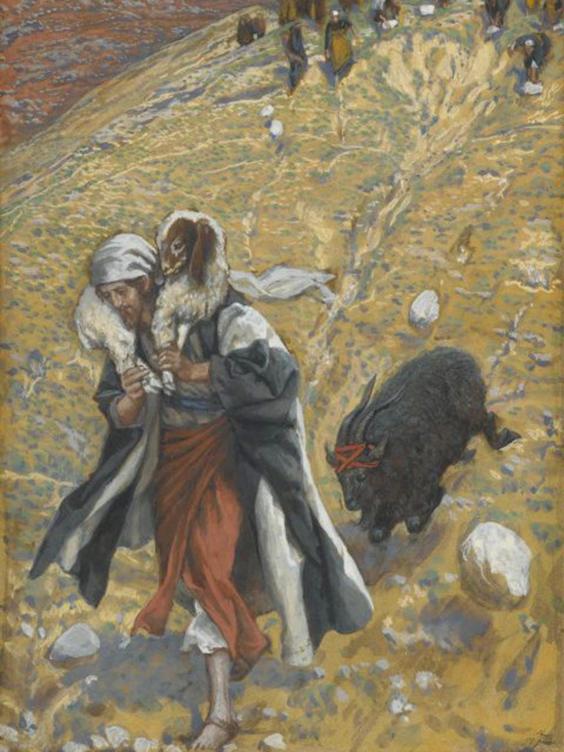

God as depicted in Michelangelo's fresco ‘The Creation of the Heavenly Bodies’ in the Sistine Chapel Michelangelo

Here’s a thing I bet not too many people know. Where are the new BBC offices in New York? Some may know the old location – past that neoclassical main post office in Manhattan, not far from the Empire State Building, going down towards the Hudson on 8th Avenue. But now we have brand new offices, with lots of glass and mind-numbing security. And they can be found on Liberty Street, just across West Street from Ground Zero. The site, in other words, of what was the Twin Towers. And therefore of 9/11. I’m living in Harlem so I went all the way downtown on the “A” train the other day to have a conversation with Rory Sutherland in London, who is omniscient in matters of marketing and advertising.

Here’s a thing I bet not too many people know. Where are the new BBC offices in New York? Some may know the old location – past that neoclassical main post office in Manhattan, not far from the Empire State Building, going down towards the Hudson on 8th Avenue. But now we have brand new offices, with lots of glass and mind-numbing security. And they can be found on Liberty Street, just across West Street from Ground Zero. The site, in other words, of what was the Twin Towers. And therefore of 9/11. I’m living in Harlem so I went all the way downtown on the “A” train the other day to have a conversation with Rory Sutherland in London, who is omniscient in matters of marketing and advertising.

There were 19 hijackers involved in 9/11, where Ground Zero now marks the World Trade Centre, but only one person was involved in the Westminster attack (Rex)

I was reminded as I came out again and gazed up at the imposing mass of the Freedom Tower, the top of which vanished into the mist, that just the week before I was going across Westminster Bridge, in the direction of the Houses of Parliament. It struck me, thinking in terms of sheer numbers, that over 15 years and several wars later, we have scaled down the damage from 19 highly organised hijackers in the 2001 attacks on America to one quasi-lone wolf this month in Westminster. But that it is also going to be practically impossible to eliminate random out-of-the-blue attacks like this one.

But I also had the feeling, probably shared by most people who were alive but not directly caught up in either Westminster or the Twin Towers back in 2001: there but for the grace of God go I. That, I thought, could have been me: the “falling man” jumping out of the 100th floor or the woman leaping off the bridge into the Thames. In other words, I was identifying entirely with the victims. If I wandered over to the 9/11 memorial I knew that I could see several thousand names recorded there for posterity. Those who died.

But I also had the feeling, probably shared by most people who were alive but not directly caught up in either Westminster or the Twin Towers back in 2001: there but for the grace of God go I. That, I thought, could have been me: the “falling man” jumping out of the 100th floor or the woman leaping off the bridge into the Thames. In other words, I was identifying entirely with the victims. If I wandered over to the 9/11 memorial I knew that I could see several thousand names recorded there for posterity. Those who died.

So I am not surprised that nearly everything that has been written (in English) in the days since the Westminster killings has been similarly slanted. “We must stand together” and all that. But it occurs to me now that “we” (whoever that may be) need to make more of an effort to get into the mind of the perpetrators and see the world from their point of view. Because it isn’t that difficult. You don’t have to be a Quranic scholar. Khalid Masood wasn’t. He was born, after all, Adrian Elms, and brought up in Tunbridge Wells (where my parents lived towards the end of their lives). He was one of “us”.

This second-thoughts moment was inspired in part by having lunch with thriller writer Lee Child, creator of the immortal Jack Reacher. I wrote a whole book which was about looking over his shoulder while he wrote one of his books (Make Me). He said, “You had one good thing in your book.” “Really?” says I. “What was that then?” “It was that bit where you call me ‘an evil mastermind bastard’. That has made me think a bit.”

When he finally worked out what was going on in “Mother’s Rest”, his sinister small American town, and gave me the big reveal, I had to point out the obvious, namely that he, the author, was just as much the bad guys of his narrative as the hero. He was the one who had dreamed up this truly evil plot. No one else. Those “hog farmers”, who were in fact something a lot worse than hog farmers, were his invention. Lee Child was shocked. Because up until that point he had been going along with the assumption of all fans that he is in fact Jack Reacher. He saw himself as the hero of his own story.

There were 19 hijackers involved in 9/11, where Ground Zero now marks the World Trade Centre, but only one person was involved in the Westminster attack (PA)

I only mention this because it strikes me that this “we are the good guys” mentality is so widespread and yet not in the least justified. Probably the most powerful case for saying, from a New York point of view, that we are the good guys was provided by René Girard, a French philosopher who became a fixture at Stanford, on the West Coast (dying in 2015). His name came up in the conversation with Rory Sutherland because he was taken up by Silicon Valley marketing moguls on account of his theory of “mimetic desire”. All of our desires, Girard would say, are mediated. They are not autonomous, but learnt, acquired, “imitated”. Therefore, they can be manufactured or re-engineered or shifted in the direction of eg buying a new smartphone or whatever. It is the key to all marketing. But Girard also took the view, more controversially, that Christianity was superior to all other religions. More advanced. More sympathetic. Morally ahead of the field.

And he also explains why it is that religion and violence are so intimately related. I know the Dalai Lama doesn’t agree. He reckons that there is no such thing as a “Muslim terrorist” or a “Buddhist terrorist” because as soon as you take up violence you are abandoning the peaceful imperatives of religion. Which is all about tolerance and sweetness and light. Oh no it isn’t, says Girard, in Violence and the Sacred. Taking a long evolutionary and anthropological view, Girard argues that sacrifice has been formative in the development of homo sapiens. Specifically, the scapegoat. We – the majority – resolve our internal divisions and strife by picking on a sacrificial victim. She/he/it is thrown to the wolves in order to overcome conflict. Greater violence is averted by virtue of some smaller but significant act of violence. All hail the Almighty who therefore deigns to spare us further suffering.

In other words, human history is dominated by the scapegoat mentality. Here I have no argument with Girard. Least of all in the United States right now, where the Scapegoater-in-chief occupies the White House. But Girard goes on to argue that Christianity is superior because (a) it agrees with him that all history is about scapegoats and (b) it incorporates this insight into the Passion narrative itself. Jesus Christ was required to become a scapegoat and thereby save humankind. But by the same token Christianity is a critique of scapegoating and enables us to get beyond it. And Girard even neatly takes comfort from the anti-Christ philosopher Nietzsche, who denounced Christianity on account of it being too soft-hearted and sentimental. Cool argument. The only problem is that it’s completely wrong.

I’ve recently been reading Harold Bloom’s analysis of the Bible in The Shadow of a Great Rock. He reminds us, if we needed reminding, that the Yahweh of the Old Testament is a wrathful freak of arbitrariness. A monstrous and unpredictable kind of god, perhaps partly because he contains a whole bunch of other lesser gods that preceded him in Mesopotamian history. So naturally he gets particularly annoyed by talk of rival gods and threatens to do very bad things to anyone who worships Baal or whoever.

And he also explains why it is that religion and violence are so intimately related. I know the Dalai Lama doesn’t agree. He reckons that there is no such thing as a “Muslim terrorist” or a “Buddhist terrorist” because as soon as you take up violence you are abandoning the peaceful imperatives of religion. Which is all about tolerance and sweetness and light. Oh no it isn’t, says Girard, in Violence and the Sacred. Taking a long evolutionary and anthropological view, Girard argues that sacrifice has been formative in the development of homo sapiens. Specifically, the scapegoat. We – the majority – resolve our internal divisions and strife by picking on a sacrificial victim. She/he/it is thrown to the wolves in order to overcome conflict. Greater violence is averted by virtue of some smaller but significant act of violence. All hail the Almighty who therefore deigns to spare us further suffering.

In other words, human history is dominated by the scapegoat mentality. Here I have no argument with Girard. Least of all in the United States right now, where the Scapegoater-in-chief occupies the White House. But Girard goes on to argue that Christianity is superior because (a) it agrees with him that all history is about scapegoats and (b) it incorporates this insight into the Passion narrative itself. Jesus Christ was required to become a scapegoat and thereby save humankind. But by the same token Christianity is a critique of scapegoating and enables us to get beyond it. And Girard even neatly takes comfort from the anti-Christ philosopher Nietzsche, who denounced Christianity on account of it being too soft-hearted and sentimental. Cool argument. The only problem is that it’s completely wrong.

I’ve recently been reading Harold Bloom’s analysis of the Bible in The Shadow of a Great Rock. He reminds us, if we needed reminding, that the Yahweh of the Old Testament is a wrathful freak of arbitrariness. A monstrous and unpredictable kind of god, perhaps partly because he contains a whole bunch of other lesser gods that preceded him in Mesopotamian history. So naturally he gets particularly annoyed by talk of rival gods and threatens to do very bad things to anyone who worships Baal or whoever.

‘Agnus-Dei: The Scapegoat’ by James Tissot, painted between 1886 and 1894

Equally, if we fast forward to the very end of the Bible (ta biblia, the little books, all bundled together) we will find a lot of rabid talk about damnation and hellfire and apocalypse and the rapture and the Beast. If I remember right George Bush Jr was a great fan of the rapture, and possibly for all I know Tony Blair likewise, while they were on their knees praying together, and looked forward to the day when all true believers would be spirited off to heaven leaving the other deluded, benighted fools behind. Christianity ticks all the boxes of extreme craziness that put it right up there with the other patriarchal sky-god religions, Judaism and Islam.

But even if it were just the passion narrative, this is still a problem for the future of humankind because it suggests that scapegoating really works. It will save us from evil. “Us” being the operative word here. Because this is the argument that every “true” religion repeats over and over again, even when it appears to be saying (like the Dalai Lama) extremely nice and tolerant things: “we” are the just and the good and the saved, and “they” aren’t. There are believers and there are infidels. Insiders and outsiders (Frank Kermode makes this the crux of his study of Mark’s gospel, The Genesis of Secrecy, dedicated “To Those Outside”). Christianity never really got over the idea of the Chosen People and the Promised Land. Girard is only exemplifying and reiterating the Christian belief in their own (as the Americans used to say while annihilating the 500 nations) “manifest destiny”.

I find myself more on the side of Brigitte Bardot than René Girard. Once mythified by Roger Vadim in And God Created Woman, she is now unfairly caricatured as an Islamophobic fascist fellow-traveller. Whereas she would, I think, point out that, in terms of sacred texts, the problem begins right back in the book of Genesis, “in the beginning”, when God says “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth”. This “dominion” idea, of humans over every other entity, just like God over humans, and man over woman, is a stupid yet corrosive binary opposition that flies in the face of our whole evolutionary history.

This holier-than-thou attitude was best summed up for me in a little pamphlet a couple of besuited evangelists once put in my hand. It contained a cartoon of the world. This is what the world looks like (in their view): there are two cliffs, with a bottomless abyss between them. On the right-hand cliff we have a nice little family of well-dressed humans, man and wife and a couple of kids (all white by the way) standing outside their neat little house, with a gleaming car parked in the driveway. On the left-hand cliff we see a bunch of dumb animals, goats and sheep and cows mainly, gazing sheepishly across at the right-hand cliff, with a kind of awe and respect.

“We” are over here, “they” are over there. Us and them. “They are animals”. How many times have we heard that recently? It’s completely insane and yet a legitimate interpretation of the Bible. This is the real problem of the sky-god religions. It’s not that they are too transcendental; they are too humanist. Too anthropocentric. They just think too highly of human beings.

I’ve become an anti-humanist. I am not going to say “Je suis Charlie”. Or (least of all) “I am Khalid Masood“ either. I want to say: I am an animal. And not be ashamed of it. Which is why, when I die, I am not going to heaven. I want to be eaten by a bear. Or possibly wolves. Or creeping things that creepeth. Or even, who knows, if they are up for it, those poor old goats that we are always sacrificing.

But even if it were just the passion narrative, this is still a problem for the future of humankind because it suggests that scapegoating really works. It will save us from evil. “Us” being the operative word here. Because this is the argument that every “true” religion repeats over and over again, even when it appears to be saying (like the Dalai Lama) extremely nice and tolerant things: “we” are the just and the good and the saved, and “they” aren’t. There are believers and there are infidels. Insiders and outsiders (Frank Kermode makes this the crux of his study of Mark’s gospel, The Genesis of Secrecy, dedicated “To Those Outside”). Christianity never really got over the idea of the Chosen People and the Promised Land. Girard is only exemplifying and reiterating the Christian belief in their own (as the Americans used to say while annihilating the 500 nations) “manifest destiny”.

I find myself more on the side of Brigitte Bardot than René Girard. Once mythified by Roger Vadim in And God Created Woman, she is now unfairly caricatured as an Islamophobic fascist fellow-traveller. Whereas she would, I think, point out that, in terms of sacred texts, the problem begins right back in the book of Genesis, “in the beginning”, when God says “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth”. This “dominion” idea, of humans over every other entity, just like God over humans, and man over woman, is a stupid yet corrosive binary opposition that flies in the face of our whole evolutionary history.

This holier-than-thou attitude was best summed up for me in a little pamphlet a couple of besuited evangelists once put in my hand. It contained a cartoon of the world. This is what the world looks like (in their view): there are two cliffs, with a bottomless abyss between them. On the right-hand cliff we have a nice little family of well-dressed humans, man and wife and a couple of kids (all white by the way) standing outside their neat little house, with a gleaming car parked in the driveway. On the left-hand cliff we see a bunch of dumb animals, goats and sheep and cows mainly, gazing sheepishly across at the right-hand cliff, with a kind of awe and respect.

“We” are over here, “they” are over there. Us and them. “They are animals”. How many times have we heard that recently? It’s completely insane and yet a legitimate interpretation of the Bible. This is the real problem of the sky-god religions. It’s not that they are too transcendental; they are too humanist. Too anthropocentric. They just think too highly of human beings.

I’ve become an anti-humanist. I am not going to say “Je suis Charlie”. Or (least of all) “I am Khalid Masood“ either. I want to say: I am an animal. And not be ashamed of it. Which is why, when I die, I am not going to heaven. I want to be eaten by a bear. Or possibly wolves. Or creeping things that creepeth. Or even, who knows, if they are up for it, those poor old goats that we are always sacrificing.

Sunday, 27 November 2016

Sunday, 3 January 2016

On Maududi - A founder of political Islam

Nadeem F Paracha in The Dawn

Abul Ala Maududi (d.1979), is considered to be one of the most influential Islamic scholars of the 20th century. He is praised for being a highly prolific and insightful intellectual and author who creatively contextualised the political role of Islam in the last century, and consequently gave birth to what became known as ‘Political Islam.’

Simultaneously, his large body of work was also severely critiqued as being contradictory and for being an inspiration to those bent on committing violence in the name of faith.

Interestingly, Maududi’s theories and commentaries received negative criticism not only from those on the left and liberal sides of the divide, but from some of his immediate religious contemporaries as well.

Nevertheless, his thesis on the state, politics and Islam, managed to influence a number of movements within and outside of Pakistan.

For example, the original ideologues of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood organisation (that eventually spread across the Arab world), were directly influenced by Maududi’s writings.

Maududi’s writings also influenced the rise of ‘Islamic’ regimes in Sudan in the 1980s, and more importantly, the same writings were recycled by the Ziaul Haq dictatorship (1977-88), to indoctrinate the initial batches of Afghan insurgents (the ‘mujahideen’), fighting against Soviet troops stationed in Afghanistan.

In the last century, the modern Islamic Utopia that Maududi was conceptualising had become the main motivation behind several political and ideological experiments in various Muslim countries.

However, 21st century politics (in the Muslim world) is not according to the kind enthusiastic reception that Maududi’s ideas received in the second half of the 20th century.

By the early 2000s, almost all experiments based on Maududi’s ideas seemed to have collapsed under their own weight. The imagined Utopia turned into a living dystopia, torn apart by mass level violence (perpetrated in the name of faith) and the gradual retardation of social and economic evolution in a number of Muslim countries, including Pakistan.

This is ironic. Because when compared to the ultimate mindset that his ideas seemed to have ended up planting within various mainstream regimes and clandestine groups, Maududi himself sounds rather broad-minded.

Born in 1903 in Aurangabad, India, Maududi’s intellectual evolution is a fascinating story of a man who, after facing bouts of existential crises, chose to interpret Islam as a political theory to address his own spiritual and ideological impasses.

He did not come raging out of a madressah, swinging a fist at the vulgarities of the modern world. On the contrary, he was born into a family that had relations with the enlightened 19th century Muslim reformist and scholar, Sir Syed Ahmed Khan.

Maududi received his early education at home through private tutors who taught him the Quran, Hadith, Arabic and Persian. At age 12, Maududi was sent to the Oriental High School whose curriculum had been arranged by famous Islamic scholar, Shibli Nomani.

Maududi was studying at a college-level Islamic institution, the Darul Aloom, when he had to rush to Bhopal to look after his ailing father. In Bhopal, he befriended the rebellious Urdu poet and writer, Niaz Fatehpuri.

Fatehpuri’s writings and poetry were highly critical of the orthodox Muslim clergy. This had left him fighting polemical battles with the ulema.

Inspired by Fatehpuri, Maududi too decided to become a writer. In 1919, the then 17-year-old Maududi moved to Delhi, where for the first time he began to study the works of Sir Syed Ahmed Khan in full. This, in turn, led Maududi to study the major works of philosophy, sociology, history and politics authored by leading European thinkers and writers.

In 1929, after resurfacing from his vigorous study of Western philosophical and political thought, Maududi published his first major book, Al-Jihad Fil-Islam. The book is largely a lament on the state of Muslim society in India and in it he attacked the British, modernist Muslims and the orthodox clergy for combining to keep Indian Muslims subdued and weak.

Writing in flowing, rhetorical Urdu, Maududi criticised the Muslim clergy for keeping Muslims away from the study of Western philosophy and science. Maududi suggested that it were these that were at the heart of Western political and economic supremacy and needed to be studied so they could then be effectively dismantled and replaced by an ‘Islamic society’.

In 1941 Maududi formed the Jamaat-i-Islami (JI). The outfit was shaped on the Leninist model of forming a ‘party of a select group of committed and knowledgeable vanguards’ who would attempt to grab state power through revolution.

In an essay that was later republished (in 1980) in a compilation of his writings, Come let us Change This World, Maududi castigated the ulema for ‘being stuck in the past’ and thus halting the emergence of new research and thinking in the field of Islamic scholarship.

He was equally critical of modernist Muslims (including Mohammad Ali Jinnah). In the same essay he lambasted them for understanding Islam through concepts constructed by the West and for believing that religion was a private matter.

Though an opponent of Jinnah and the creation of Pakistan (because he theorised that an ‘Islamic State’ could not be enacted by ‘Westernised Muslims’), Maududi did migrate to the new Muslim-majority country once it came into being in 1947.

In a string of books, mainly Khilafat-o-Malukiyat, Deen-i-Haq, Islamic Law and Constitution and Economic System of Islam, Maududi laid out his precepts of the modern-day ‘Islamic State’.

He was adamant about the need to gain state power to impose his principles of an Islamic State, but cautioned that the society first needed to be Islamised from below (through evangelical action), for such a state to begin imposing Islamic Laws.

In these books he was the first Islamic scholar to use the term ‘Islamic ideology’ (in a political context). The term was later rephrased as ‘Political Islam’ by the western scholarship on the subject.

In 1977 when Maududi agreed to support the Ziaul Haq dictatorship, he was criticised for attempting to grab state power through a Machiavellian military dictator.

Maududi’s decision sparked an intense critique of his ideas by the modernist Islamic scholar, Dr Fazal Rehman Malik. In his book, Islam and Modernity, Dr Malik described Maududi as a populist journalist, rather than a scholar. Malik suggested that Maududi’s writings were ‘shallow’ and crafted only to bag the attention of muddled young men craving for an imagined faith-driven Utopia.

Maududi’s body of work is remarkable in its proficiency and creativity. And indeed, it is also contradictory. He used Western political concepts of the state to explain the modern idea of the Islamic State; and yet he accused modernist Muslims of understanding Islam through Western constructs. He saw no space for monarchies in Islam, yet was entirely uncritical of conservative Arab monarchies. He would often prefix the word Islam in front of various Western economic and political ideas — (Islamic-Economics, Islamic-Banking and Islamic-Constitution) — and yet he reacted aggressively towards the idea of ‘Islamic-Socialism’ that came from his leftist opponents in the 1960s.

Writing in the Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought, Political Anthropologist, Professor Irfan Ahmed, suggested that there was not one Maududi, but many.

He wrote that elements of Leninism, Hegel’s dualism, Jalaluddin Afghani’s Pan-Islamism and various other modern political theories can be found in Maududi’s thesis.

Perhaps this is why Maududi’s ideas managed to appeal to various sections of the urban Muslim middle-classes; modern conservative Muslim movements; and all the way to the more anarchic and reactionary forces.

But the question is, had Maududi been alive today, which one of the many Maududis would he have been most comfortable with in a Muslim world now crammed with raging dystopias?

Abul Ala Maududi (d.1979), is considered to be one of the most influential Islamic scholars of the 20th century. He is praised for being a highly prolific and insightful intellectual and author who creatively contextualised the political role of Islam in the last century, and consequently gave birth to what became known as ‘Political Islam.’

Simultaneously, his large body of work was also severely critiqued as being contradictory and for being an inspiration to those bent on committing violence in the name of faith.

Interestingly, Maududi’s theories and commentaries received negative criticism not only from those on the left and liberal sides of the divide, but from some of his immediate religious contemporaries as well.

Nevertheless, his thesis on the state, politics and Islam, managed to influence a number of movements within and outside of Pakistan.

For example, the original ideologues of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood organisation (that eventually spread across the Arab world), were directly influenced by Maududi’s writings.

Maududi’s writings also influenced the rise of ‘Islamic’ regimes in Sudan in the 1980s, and more importantly, the same writings were recycled by the Ziaul Haq dictatorship (1977-88), to indoctrinate the initial batches of Afghan insurgents (the ‘mujahideen’), fighting against Soviet troops stationed in Afghanistan.

In the last century, the modern Islamic Utopia that Maududi was conceptualising had become the main motivation behind several political and ideological experiments in various Muslim countries.

However, 21st century politics (in the Muslim world) is not according to the kind enthusiastic reception that Maududi’s ideas received in the second half of the 20th century.

By the early 2000s, almost all experiments based on Maududi’s ideas seemed to have collapsed under their own weight. The imagined Utopia turned into a living dystopia, torn apart by mass level violence (perpetrated in the name of faith) and the gradual retardation of social and economic evolution in a number of Muslim countries, including Pakistan.

This is ironic. Because when compared to the ultimate mindset that his ideas seemed to have ended up planting within various mainstream regimes and clandestine groups, Maududi himself sounds rather broad-minded.

Born in 1903 in Aurangabad, India, Maududi’s intellectual evolution is a fascinating story of a man who, after facing bouts of existential crises, chose to interpret Islam as a political theory to address his own spiritual and ideological impasses.

He did not come raging out of a madressah, swinging a fist at the vulgarities of the modern world. On the contrary, he was born into a family that had relations with the enlightened 19th century Muslim reformist and scholar, Sir Syed Ahmed Khan.

Maududi received his early education at home through private tutors who taught him the Quran, Hadith, Arabic and Persian. At age 12, Maududi was sent to the Oriental High School whose curriculum had been arranged by famous Islamic scholar, Shibli Nomani.

Maududi was studying at a college-level Islamic institution, the Darul Aloom, when he had to rush to Bhopal to look after his ailing father. In Bhopal, he befriended the rebellious Urdu poet and writer, Niaz Fatehpuri.

Fatehpuri’s writings and poetry were highly critical of the orthodox Muslim clergy. This had left him fighting polemical battles with the ulema.

Inspired by Fatehpuri, Maududi too decided to become a writer. In 1919, the then 17-year-old Maududi moved to Delhi, where for the first time he began to study the works of Sir Syed Ahmed Khan in full. This, in turn, led Maududi to study the major works of philosophy, sociology, history and politics authored by leading European thinkers and writers.

In 1929, after resurfacing from his vigorous study of Western philosophical and political thought, Maududi published his first major book, Al-Jihad Fil-Islam. The book is largely a lament on the state of Muslim society in India and in it he attacked the British, modernist Muslims and the orthodox clergy for combining to keep Indian Muslims subdued and weak.

Writing in flowing, rhetorical Urdu, Maududi criticised the Muslim clergy for keeping Muslims away from the study of Western philosophy and science. Maududi suggested that it were these that were at the heart of Western political and economic supremacy and needed to be studied so they could then be effectively dismantled and replaced by an ‘Islamic society’.

In 1941 Maududi formed the Jamaat-i-Islami (JI). The outfit was shaped on the Leninist model of forming a ‘party of a select group of committed and knowledgeable vanguards’ who would attempt to grab state power through revolution.

In an essay that was later republished (in 1980) in a compilation of his writings, Come let us Change This World, Maududi castigated the ulema for ‘being stuck in the past’ and thus halting the emergence of new research and thinking in the field of Islamic scholarship.

He was equally critical of modernist Muslims (including Mohammad Ali Jinnah). In the same essay he lambasted them for understanding Islam through concepts constructed by the West and for believing that religion was a private matter.

Though an opponent of Jinnah and the creation of Pakistan (because he theorised that an ‘Islamic State’ could not be enacted by ‘Westernised Muslims’), Maududi did migrate to the new Muslim-majority country once it came into being in 1947.

In a string of books, mainly Khilafat-o-Malukiyat, Deen-i-Haq, Islamic Law and Constitution and Economic System of Islam, Maududi laid out his precepts of the modern-day ‘Islamic State’.

He was adamant about the need to gain state power to impose his principles of an Islamic State, but cautioned that the society first needed to be Islamised from below (through evangelical action), for such a state to begin imposing Islamic Laws.

In these books he was the first Islamic scholar to use the term ‘Islamic ideology’ (in a political context). The term was later rephrased as ‘Political Islam’ by the western scholarship on the subject.

In 1977 when Maududi agreed to support the Ziaul Haq dictatorship, he was criticised for attempting to grab state power through a Machiavellian military dictator.

Maududi’s decision sparked an intense critique of his ideas by the modernist Islamic scholar, Dr Fazal Rehman Malik. In his book, Islam and Modernity, Dr Malik described Maududi as a populist journalist, rather than a scholar. Malik suggested that Maududi’s writings were ‘shallow’ and crafted only to bag the attention of muddled young men craving for an imagined faith-driven Utopia.

Maududi’s body of work is remarkable in its proficiency and creativity. And indeed, it is also contradictory. He used Western political concepts of the state to explain the modern idea of the Islamic State; and yet he accused modernist Muslims of understanding Islam through Western constructs. He saw no space for monarchies in Islam, yet was entirely uncritical of conservative Arab monarchies. He would often prefix the word Islam in front of various Western economic and political ideas — (Islamic-Economics, Islamic-Banking and Islamic-Constitution) — and yet he reacted aggressively towards the idea of ‘Islamic-Socialism’ that came from his leftist opponents in the 1960s.

Writing in the Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought, Political Anthropologist, Professor Irfan Ahmed, suggested that there was not one Maududi, but many.

He wrote that elements of Leninism, Hegel’s dualism, Jalaluddin Afghani’s Pan-Islamism and various other modern political theories can be found in Maududi’s thesis.

Perhaps this is why Maududi’s ideas managed to appeal to various sections of the urban Muslim middle-classes; modern conservative Muslim movements; and all the way to the more anarchic and reactionary forces.

But the question is, had Maududi been alive today, which one of the many Maududis would he have been most comfortable with in a Muslim world now crammed with raging dystopias?

Sunday, 15 November 2015

India is more sensitive now, not more intolerant

Swaminathan Anklesaria Aiyer in the Times of India

Narendra Modi said in London that “India will not tolerate intolerance”. Secular critics jeered, since the BJP had raised the communal temperature during the Bihar election. Over 50 writers have returned national awards in protest against intolerance. They cite the Dadri beef lynching, murder of three prominent writers, and the ink attack on Sudheendra Kulkarni.

But it’s fiction to pretend that India used to be tolerant and has turned intolerant today. Intolerance has actually diminished substantially. Nothing can compare with the communal killings at Partition in 1947. Communal riots have continued with sickening regularity since then, but diminished in recent years, with the notable exception of 2002.

Ambedkar said violence against dalits was the worst of all. The Indian Constitution banned caste discrimination, yet caste violence remained embedded in society. Dalits could be attacked, raped, killed and humiliated at will, with impunity, by upper castes. This was also true, to a lesser extent, of other backward castes. Villages did not have riots, yet their very ethos was based on the most oppressive threat of caste violence. Fortunately, caste discrimination has fallen gradually, though it remains a harsh reality. The last two decades have seen the rise of almost 4,000 dalit millionaire businessmen, something unthinkable in the past.

Modi will never be forgiven by many for the 2002 Gujarat riots. But JS Bandukwala, the Muslim professor who barely escaped mob murder, told me that the 1969 Gujarat riots were worse. Yet the then Congress chief minister did not resign or become a social pariah. Regional newspapers relegated many of the 1969 incidents to inside pages.

Why? What has changed? The answer is the rise of private TV. This has brought the awfulness of communal violence into every household in every language. In 1969, there was no TV. All India Radio had a radio monopoly. The government deliberately played down the riots, to try and reduce communal tension. Newspapers those days had shoestring budgets. Reporters did not rush from all corners of India to Gujarat, or go into every affected town. Most newspapers depended on briefings from the home ministry, and co-operated with government pleas to play down killings, to douse communal tensions. No photos were published of the blood and gore. Newspapers avoided saying “Hindu” or “Muslim,” and just said “people of another community”.

Media reportage was stronger during the Babri Masjid agitation. But there was no private TV in 1992 to expose the gore and violence of the masjid destruction, or the horrific post-masjid riots.

By the 2002 riots in Gujarat, a media revolution had occurred. Private TV channels with ample resources sent reporters to every riot site. They competed in exposing communal hate and gore. Far from hiding the identity of communities, TV highlighted the Hindu-Muslim divide starkly. Far from trying to douse tension, TV competed in highlighting horrific events, including even fictions like the supposed pregnant woman whose womb was slit by Hindu fanatics.

Did the aggressive media in 2002 increase communal tensions and violence compared with 1969? Quite possibly. Yet the media were right to pull no punches. By conveying the horror of 2002 all over India, they created a revulsion that Modi himself heeded in his next 12 years in Gujarat. Subsequently too, media competition greatly increased coverage of all sorts of discrimination and violence. Events once buried in the inside pages of newspapers became prime time TV news. This improved public sensitivity to discrimination and thuggery, and hence government accountability.

The BJP says it is being treated unfairly today, since there have been a few stray communal incidents but no riots. The BJP was not behind the Dadri or Jammu lynchings, or the killing of rationalist writers, and was actually a victim in the ink-throwing incident. However, BJP spokesmen have found it almost impossible to condemn these incidents outright, and sought to convert the cow into a vote-gaining tactic in Bihar. This BJP hypocrisy has rightly been condemned. Yet its current sins are absolutely nothing compared with 1992 or 2002.

Intolerance has not worsened. Rather, our civic standards have improved, and we are quicker to get disgusted. Competitive TV has made us much more easily horrified, terrified, alarmed, disgusted, and angry. That’s an excellent development. Private TV has not just improved entertainment and variety, but also hugely increased our sensitivity to all that’s wrong in society, to all its horrors and atrocities.

This is a major gain of economic liberalization. In 1991, leftists opposed private TV channels, saying these would be tools in the hands of big business. What rubbish. Private TV has empowered the citizen to view the horrors that government channels had always downplayed and sanitized. That has raised our civic standards, lowering our thresholds for anger and revulsion. Hurrah!

Monday, 12 October 2015

End the Sena’s veto power

Editorial in The Hindu

What the Shiv Sena could earlier do only with threats of violence, it can now do with a mere letter or an appeal. The organisers of concerts planned in Mumbai and Pune by Pakistani ghazal singer Ghulam Ali were quick to cancel the programmes after the Shiv Sena asked them not to host a singer belonging to a “country which is firing bullets at Indians”. A meeting with Sena supremo Uddhav Thackeray must have convinced the organisers that the letter of request to cancel the show had the sanction of those at the very top of the Sena leadership, and that the “request” was no less than a threat in disguise. Now that it is in power, the Sena can effectively veto any cultural programme without even organising a public protest. The lesson that the organisers would have taken from the Sena’s missive is that no help would be forthcoming from officialdom in a State where a party that draws support from lumpen elements is in power. From digging up the cricket pitch and forming balidani jathas to stop matches between India and Pakistan, the Sena is known to oppose any kind of cultural or sporting interaction between India and Pakistan. Now that it is in power, the Sena seems intent on its agenda of imposing a boycott on all things Pakistani without resorting to open threats or violence.

The irrationality seems to have struck all but the most ardent of the Sena’s supporters. While Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal spoke to Ghulam Ali and persuaded him to agree to come to Delhi for a concert in December, West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee offered to host him in Kolkata. But the issue is far more important than Ghulam Ali being able to perform in India. This is not on whether art, culture and sport can bring people together or worsen relations between nations. Whether they do one or the other depends on the peoples involved, and not on some intrinsic quality of these forms. The issue actually relates to the unbridled political power that the Sena wields in Maharashtra, a power that is not drawn from any electoral mandate, a power that is not accountable to any democratic institution. The Sena quite arrogantly assumes it can speak for all people when it asks for a show to be cancelled “considering the emotions of the citizens”. If the Sena was so offended by a Pakistani artiste performing in Maharashtra, it could have asked its supporters to stay away from it. The Sena’s senior ally in government, the BJP, and Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis, need to guard against a repeat of such incidents. What is at stake is not the right of a Pakistani artiste to perform in India, but the right of Indians to decide who they can listen to or watch in India.