'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label narrative. Show all posts

Showing posts with label narrative. Show all posts

Thursday, 11 January 2024

Tuesday, 12 December 2023

Friday, 23 June 2023

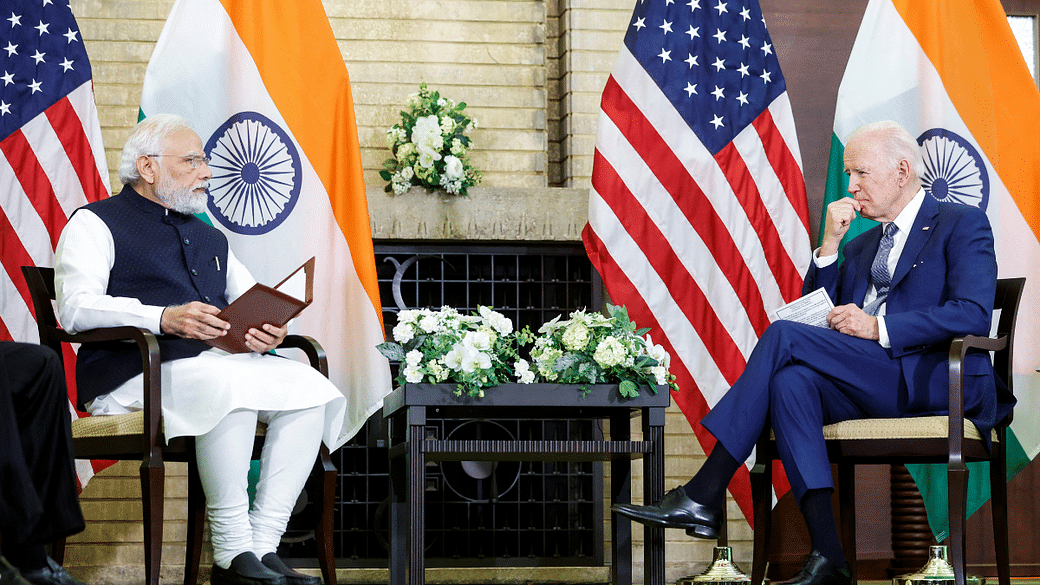

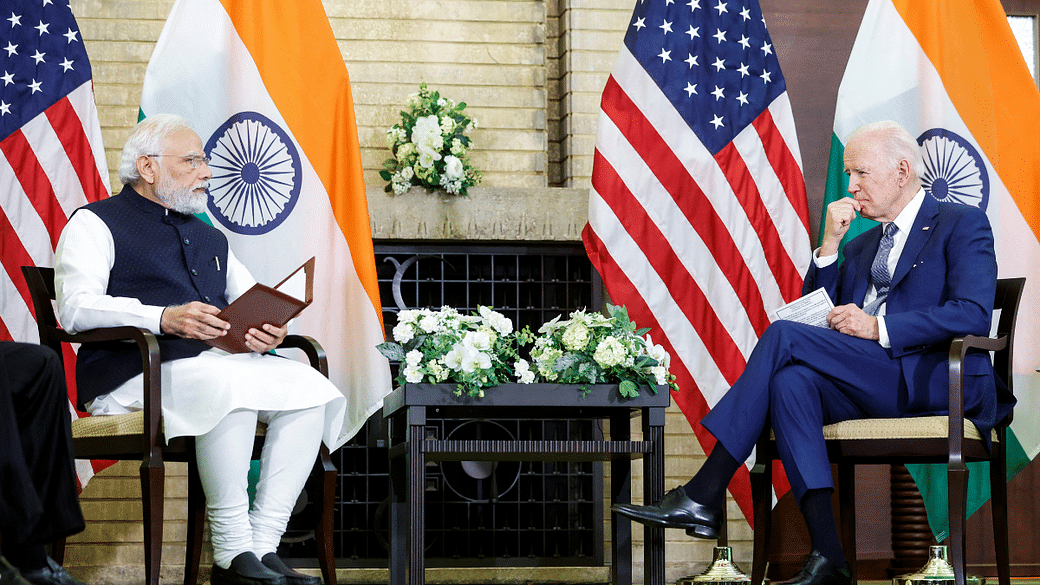

Attacking Modi in US shows IAMC using Indian Muslims as pawns

Narratives propagated by the likes of IAMC often rely on select stories, and it is concerning that the Western media accepts them without delving into the ground realities writes AMANA BEGAM in The Print

While PM Modi’s state visit to the US is being noticed across world capitals, his opponents in the US are busy doing what they love most — criticising him for his human rights record and accusing his government of suppressing dissent and implementing discriminatory policies against Muslims and other minority groups.

It is not uncommon to witness certain groups initiating campaigns on foreign soil, portraying a narrative of persecution of Indian Muslims. Raising one’s voice for human rights is indeed a crucial and meaningful endeavour. However, challenges arise when human rights issues are exploited as a tool for propaganda, distorting and manipulating the truth about a nation.

Being an Indian Pasmanda Muslim, I frequently witness the propagation of these false narratives against my homeland. Hence it is my sincere duty to raise my voice against them. India, as a nation, not only embraces the homeland of over one billion Hindus but also stands as a diverse abode for 200 million Muslims, 28 million Christians, 21 million Sikhs, 12 million Buddhists, 4.45 million Jains, and countless others.

It is truly disheartening to witness the portrayal of a nation with such a rich and inclusive history as a place where Muslims are purportedly on the verge of facing genocide. Such narratives often rely on select stories, and it is concerning that the Western media often accepts them without delving into the ground realities and comprehending the policies implemented by the Indian State. It is important for such storytellers to seek a more nuanced understanding by examining the comprehensive picture and taking into account the complexities and intricacies.

To begin with, organisations like the Indian American Muslim Council (IAMC) claim to represent the voice of Indian Muslims. However, they frequently disseminate false and misleading information through their tweets. Moreover, there have been instances where their tweets have been provocative and inflammatory. For instance, they tweeted an unsubstantiated claim stating that all victims in the Delhi riots were Muslims. This organisation has scheduled a protest outside the White House, which raises legitimate questions about their true intentions– do they genuinely prioritise the welfare of Indian Muslims or have ulterior motives and agendas at play?

Indian Muslims, stop being a pawn of anti-India forces

It is high time the Western media and geopolitical interest groups refrain from exploiting the term “Indian Muslims” for their own agendas. As for Indian Muslims, it is important that they themselves comprehend how they are being manipulated as pawns on the global stage, working against their own nation’s interests. It is imperative for them to speak out against these false narratives. We lead peaceful lives, enjoy equal rights and opportunities, have the freedom to practise our religion and make choices, and receive our fair share of benefits from welfare schemes run by the government. Our future is intertwined with our nation’s interests, and anything that generates an anti-India narrative ultimately goes against our own well-being.

Organisations like IAMC, which have no genuine connection with Indian Muslims, falsely claim to represent us while using us as pawns to further their own agendas. It is essential for Muslim intellectuals to see through these manipulations. First, the Muslim community was exploited as a mere vote bank. Now there is a risk of them being used as tools to perpetuate an anti-India narrative.

Examine Western media bias

The Western media has consistently portrayed a negative image of India since its Independence. Interestingly, failed states and countries in the middle of civil wars receive minimal attention.

PM Modi, during a national executive meeting of the BJP, clearly expressed a desire for outreach to the Muslim community, acknowledging that many within the community wish to connect with the party. He emphasised the importance of engaging with not only the economically disadvantaged Pasmanda and Bora Muslims but also educated Muslims. Previously, Modi has highlighted the integration of Pasmanda Muslims with the BJP, urging positive programmes to attract their support.

When BJP leaders have made objectionable statements about Muslims, leading to a tense atmosphere in the country, the party has taken disciplinary action against them too. Under the Modi government, a significant number of minority students have received education scholarships, surpassing previous administrations. Muslim women beneficiaries have expressed their gratitude for various government schemes, such as free ration, the abolition of instant divorce practices, free Covid vaccinations, Ujjawala cooking gas connections, and free housing, which have improved their lives. These initiatives demonstrate efforts to ensure the inclusion and well-being of Muslim communities in India.

It is important to address how Western media and human rights organisations often depict Indian Muslims as ostracised and living in a genocidal environment. For instance, the IAMC played a significant role in lobbying against India in 2019, leading to US Commission on International Religious Freedom recommending India to be blacklisted. For four consecutive years, the USCIRF has advised the US administration to designate India as a “Country of Particular Concern.” Ironically, in their assessments, they did not take into account the reality experienced by Indian Muslims. According to Pew Research, 98 per cent of Indian Muslims are free to practise their religion without hindrance. This stark contrast highlights the disconnect between the exaggerated narratives and the ground realities of religious freedom for Indian Muslims.

Don’t weaponise discourse

In their commentary, Western media and human rights organisations fail to carry voices of ordinary Indian Muslims. Providing a comprehensive and accurate understanding, based on data, helps avoid weaponisation of narratives that serve geopolitical interests.

Data often highlights the disparities in perceptions of discrimination among different communities. According to the Pew study, 80 per cent of African-Americans, 46 per cent of Hispanic Americans, and 42 per cent of Asian Americans stated they experience “a lot of discrimination” in the US. In comparison, 24 per cent of Indian Muslims say that there is widespread discrimination against them in India. Furthermore, the majority of Indian Muslims expressed pride in their Indian identity.

These statistics challenge the narrative of widespread persecution of Indian Muslims within their own nation. It raises the question of whether the same level of scrutiny should be applied to the United States, considering the reported discrimination experienced by minority communities there. It prompts us to reflect on whether the labelling of human rights violations should be applied selectively. And what explains the timing of such mongering — just before a State head is about to visit the country.

While PM Modi’s state visit to the US is being noticed across world capitals, his opponents in the US are busy doing what they love most — criticising him for his human rights record and accusing his government of suppressing dissent and implementing discriminatory policies against Muslims and other minority groups.

It is not uncommon to witness certain groups initiating campaigns on foreign soil, portraying a narrative of persecution of Indian Muslims. Raising one’s voice for human rights is indeed a crucial and meaningful endeavour. However, challenges arise when human rights issues are exploited as a tool for propaganda, distorting and manipulating the truth about a nation.

Being an Indian Pasmanda Muslim, I frequently witness the propagation of these false narratives against my homeland. Hence it is my sincere duty to raise my voice against them. India, as a nation, not only embraces the homeland of over one billion Hindus but also stands as a diverse abode for 200 million Muslims, 28 million Christians, 21 million Sikhs, 12 million Buddhists, 4.45 million Jains, and countless others.

It is truly disheartening to witness the portrayal of a nation with such a rich and inclusive history as a place where Muslims are purportedly on the verge of facing genocide. Such narratives often rely on select stories, and it is concerning that the Western media often accepts them without delving into the ground realities and comprehending the policies implemented by the Indian State. It is important for such storytellers to seek a more nuanced understanding by examining the comprehensive picture and taking into account the complexities and intricacies.

To begin with, organisations like the Indian American Muslim Council (IAMC) claim to represent the voice of Indian Muslims. However, they frequently disseminate false and misleading information through their tweets. Moreover, there have been instances where their tweets have been provocative and inflammatory. For instance, they tweeted an unsubstantiated claim stating that all victims in the Delhi riots were Muslims. This organisation has scheduled a protest outside the White House, which raises legitimate questions about their true intentions– do they genuinely prioritise the welfare of Indian Muslims or have ulterior motives and agendas at play?

Indian Muslims, stop being a pawn of anti-India forces

It is high time the Western media and geopolitical interest groups refrain from exploiting the term “Indian Muslims” for their own agendas. As for Indian Muslims, it is important that they themselves comprehend how they are being manipulated as pawns on the global stage, working against their own nation’s interests. It is imperative for them to speak out against these false narratives. We lead peaceful lives, enjoy equal rights and opportunities, have the freedom to practise our religion and make choices, and receive our fair share of benefits from welfare schemes run by the government. Our future is intertwined with our nation’s interests, and anything that generates an anti-India narrative ultimately goes against our own well-being.

Organisations like IAMC, which have no genuine connection with Indian Muslims, falsely claim to represent us while using us as pawns to further their own agendas. It is essential for Muslim intellectuals to see through these manipulations. First, the Muslim community was exploited as a mere vote bank. Now there is a risk of them being used as tools to perpetuate an anti-India narrative.

Examine Western media bias

The Western media has consistently portrayed a negative image of India since its Independence. Interestingly, failed states and countries in the middle of civil wars receive minimal attention.

PM Modi, during a national executive meeting of the BJP, clearly expressed a desire for outreach to the Muslim community, acknowledging that many within the community wish to connect with the party. He emphasised the importance of engaging with not only the economically disadvantaged Pasmanda and Bora Muslims but also educated Muslims. Previously, Modi has highlighted the integration of Pasmanda Muslims with the BJP, urging positive programmes to attract their support.

When BJP leaders have made objectionable statements about Muslims, leading to a tense atmosphere in the country, the party has taken disciplinary action against them too. Under the Modi government, a significant number of minority students have received education scholarships, surpassing previous administrations. Muslim women beneficiaries have expressed their gratitude for various government schemes, such as free ration, the abolition of instant divorce practices, free Covid vaccinations, Ujjawala cooking gas connections, and free housing, which have improved their lives. These initiatives demonstrate efforts to ensure the inclusion and well-being of Muslim communities in India.

It is important to address how Western media and human rights organisations often depict Indian Muslims as ostracised and living in a genocidal environment. For instance, the IAMC played a significant role in lobbying against India in 2019, leading to US Commission on International Religious Freedom recommending India to be blacklisted. For four consecutive years, the USCIRF has advised the US administration to designate India as a “Country of Particular Concern.” Ironically, in their assessments, they did not take into account the reality experienced by Indian Muslims. According to Pew Research, 98 per cent of Indian Muslims are free to practise their religion without hindrance. This stark contrast highlights the disconnect between the exaggerated narratives and the ground realities of religious freedom for Indian Muslims.

Don’t weaponise discourse

In their commentary, Western media and human rights organisations fail to carry voices of ordinary Indian Muslims. Providing a comprehensive and accurate understanding, based on data, helps avoid weaponisation of narratives that serve geopolitical interests.

Data often highlights the disparities in perceptions of discrimination among different communities. According to the Pew study, 80 per cent of African-Americans, 46 per cent of Hispanic Americans, and 42 per cent of Asian Americans stated they experience “a lot of discrimination” in the US. In comparison, 24 per cent of Indian Muslims say that there is widespread discrimination against them in India. Furthermore, the majority of Indian Muslims expressed pride in their Indian identity.

These statistics challenge the narrative of widespread persecution of Indian Muslims within their own nation. It raises the question of whether the same level of scrutiny should be applied to the United States, considering the reported discrimination experienced by minority communities there. It prompts us to reflect on whether the labelling of human rights violations should be applied selectively. And what explains the timing of such mongering — just before a State head is about to visit the country.

Sunday, 7 May 2023

Why the Technology = Progress narrative must be challenged

John Naughton in The Guardian

Those who cannot remember the past,” wrote the American philosopher George Santayana in 1905, “are condemned to repeat it.” And now, 118 years later, here come two American economists with the same message, only with added salience, for they are addressing a world in which a small number of giant corporations are busy peddling a narrative that says, basically, that what is good for them is also good for the world.

That this narrative is self-serving is obvious, as is its implied message: that they should be allowed to get on with their habits of “creative destruction” (to use Joseph Schumpeter’s famous phrase) without being troubled by regulation. Accordingly, any government that flirts with the idea of reining in corporate power should remember that it would then be standing in the way of “progress”: for it is technology that drives history and anything that obstructs it is doomed to be roadkill.

One of the many useful things about this formidable (560-page) tome is its demolition of the tech narrative’s comforting equation of technology with “progress”. Of course the fact that our lives are infinitely richer and more comfortable than those of the feudal serfs we would have been in the middle ages owes much to technological advances. Even the poor in western societies enjoy much higher living standards today than three centuries ago, and live healthier, longer lives.

But a study of the past 1,000 years of human development, Acemoglu and Johnson argue, shows that “the broad-based prosperity of the past was not the result of any automatic, guaranteed gains of technological progress… Most people around the globe today are better off than our ancestors because citizens and workers in earlier industrial societies organised, challenged elite-dominated choices about technology and work conditions, and forced ways of sharing the gains from technical improvements more equitably.”

Acemoglu and Johnson begin their Cook’s tour of the past millennium with the puzzle of how dominant narratives – like that which equates technological development with progress – get established. The key takeaway is unremarkable but critical: those who have power define the narrative. That’s how banks get to be thought of as “too big to fail”, or why questioning tech power is “luddite”. But their historical survey really gets under way with an absorbing account of the evolution of agricultural technologies from the neolithic age to the medieval and early modern eras. They find that successive developments “tended to enrich and empower small elites while generating few benefits for agricultural workers: peasants lacked political and social power, and the path of technology followed the vision of a narrow elite.”

A similar moral is extracted from their reinterpretation of the Industrial Revolution. This focuses on the emergence of a newly emboldened middle class of entrepreneurs and businessmen whose vision rarely included any ideas of social inclusion and who were obsessed with the possibilities of steam-driven automation for increasing profits and reducing costs.

The shock of the second world war led to a brief interruption in the inexorable trend of continuous technological development combined with increasing social exclusion and inequality. And the postwar years saw the rise of social democratic regimes focused on Keynesian economics, welfare states and shared prosperity. But all of this changed in the 1970s with the neoliberal turn and the subsequent evolution of the democracies we have today, in which enfeebled governments pay obeisance to giant corporations – more powerful and profitable than anything since the East India Company. These create astonishing wealth for a tiny elite (not to mention lavish salaries and bonuses for their executives) while the real incomes of ordinary people have remained stagnant, precarity rules and inequality returning to pre-1914 levels.

Coincidentally, this book arrives at an opportune moment, when digital technology, currently surfing on a wave of irrational exuberance about ubiquitous AI, is booming, while the idea of shared prosperity has seemingly become a wistful pipe dream. So is there anything we might learn from the history so graphically recounted by Acemoglu and Johnson?

Answer: yes. And it’s to be found in the closing chapter, which comes up with a useful list of critical steps that democracies must take to ensure that the proceeds of the next technological wave are more generally shared among their populations. Interestingly, some of the ideas it explores have a venerable provenance, reaching back to the progressive movement that brought the robber barons of the early 20th century to heel.

There are three things that need to be done by a modern progressive movement. First, the technology-equals-progress narrative has to be challenged and exposed for what it is: a convenient myth propagated by a huge industry and its acolytes in government, the media and (occasionally) academia. The second is the need to cultivate and foster countervailing powers – which critically should include civil society organisations, activists and contemporary versions of trade unions. And finally, there is a need for progressive, technically informed policy proposals, and the fostering of thinktanks and other institutions that can supply a steady flow of ideas about how digital technology can be repurposed for human flourishing rather than exclusively for private profit.

None of this is rocket science. It can be done. And it needs to be done if liberal democracies are to survive the next wave of technological evolution and the catastrophic acceleration of inequality that it will bring. So – who knows? Maybe this time we might really learn something from history.

Those who cannot remember the past,” wrote the American philosopher George Santayana in 1905, “are condemned to repeat it.” And now, 118 years later, here come two American economists with the same message, only with added salience, for they are addressing a world in which a small number of giant corporations are busy peddling a narrative that says, basically, that what is good for them is also good for the world.

That this narrative is self-serving is obvious, as is its implied message: that they should be allowed to get on with their habits of “creative destruction” (to use Joseph Schumpeter’s famous phrase) without being troubled by regulation. Accordingly, any government that flirts with the idea of reining in corporate power should remember that it would then be standing in the way of “progress”: for it is technology that drives history and anything that obstructs it is doomed to be roadkill.

One of the many useful things about this formidable (560-page) tome is its demolition of the tech narrative’s comforting equation of technology with “progress”. Of course the fact that our lives are infinitely richer and more comfortable than those of the feudal serfs we would have been in the middle ages owes much to technological advances. Even the poor in western societies enjoy much higher living standards today than three centuries ago, and live healthier, longer lives.

But a study of the past 1,000 years of human development, Acemoglu and Johnson argue, shows that “the broad-based prosperity of the past was not the result of any automatic, guaranteed gains of technological progress… Most people around the globe today are better off than our ancestors because citizens and workers in earlier industrial societies organised, challenged elite-dominated choices about technology and work conditions, and forced ways of sharing the gains from technical improvements more equitably.”

Acemoglu and Johnson begin their Cook’s tour of the past millennium with the puzzle of how dominant narratives – like that which equates technological development with progress – get established. The key takeaway is unremarkable but critical: those who have power define the narrative. That’s how banks get to be thought of as “too big to fail”, or why questioning tech power is “luddite”. But their historical survey really gets under way with an absorbing account of the evolution of agricultural technologies from the neolithic age to the medieval and early modern eras. They find that successive developments “tended to enrich and empower small elites while generating few benefits for agricultural workers: peasants lacked political and social power, and the path of technology followed the vision of a narrow elite.”

A similar moral is extracted from their reinterpretation of the Industrial Revolution. This focuses on the emergence of a newly emboldened middle class of entrepreneurs and businessmen whose vision rarely included any ideas of social inclusion and who were obsessed with the possibilities of steam-driven automation for increasing profits and reducing costs.

The shock of the second world war led to a brief interruption in the inexorable trend of continuous technological development combined with increasing social exclusion and inequality. And the postwar years saw the rise of social democratic regimes focused on Keynesian economics, welfare states and shared prosperity. But all of this changed in the 1970s with the neoliberal turn and the subsequent evolution of the democracies we have today, in which enfeebled governments pay obeisance to giant corporations – more powerful and profitable than anything since the East India Company. These create astonishing wealth for a tiny elite (not to mention lavish salaries and bonuses for their executives) while the real incomes of ordinary people have remained stagnant, precarity rules and inequality returning to pre-1914 levels.

Coincidentally, this book arrives at an opportune moment, when digital technology, currently surfing on a wave of irrational exuberance about ubiquitous AI, is booming, while the idea of shared prosperity has seemingly become a wistful pipe dream. So is there anything we might learn from the history so graphically recounted by Acemoglu and Johnson?

Answer: yes. And it’s to be found in the closing chapter, which comes up with a useful list of critical steps that democracies must take to ensure that the proceeds of the next technological wave are more generally shared among their populations. Interestingly, some of the ideas it explores have a venerable provenance, reaching back to the progressive movement that brought the robber barons of the early 20th century to heel.

There are three things that need to be done by a modern progressive movement. First, the technology-equals-progress narrative has to be challenged and exposed for what it is: a convenient myth propagated by a huge industry and its acolytes in government, the media and (occasionally) academia. The second is the need to cultivate and foster countervailing powers – which critically should include civil society organisations, activists and contemporary versions of trade unions. And finally, there is a need for progressive, technically informed policy proposals, and the fostering of thinktanks and other institutions that can supply a steady flow of ideas about how digital technology can be repurposed for human flourishing rather than exclusively for private profit.

None of this is rocket science. It can be done. And it needs to be done if liberal democracies are to survive the next wave of technological evolution and the catastrophic acceleration of inequality that it will bring. So – who knows? Maybe this time we might really learn something from history.

Wednesday, 29 March 2023

Thursday, 29 December 2022

Wednesday, 30 November 2022

Friday, 4 February 2022

Thursday, 13 January 2022

Wednesday, 22 December 2021

Monday, 13 September 2021

Wednesday, 8 September 2021

Wednesday, 11 August 2021

Wednesday, 3 March 2021

Monday, 8 February 2021

Monday, 6 July 2020

A 'Mild Attack' of Corona could be Dangerously Misleading

Otherwise healthy people who thought they recovered from coronavirus are reporting persistent and strange symptoms - including strokes writes Adrienne Matei in The Guardian

‘It’s important to keep in mind how little we truly know about this vastly complicated disease.’ Photograph: Yara Nardi/Reuters

Conventional wisdom suggests that when a sickness is mild, it’s not too much to worry about. But if you’re taking comfort in World Health Organization reports that over 80% of global Covid-19 cases are mild or asymptomatic, think again. As virologists race to understand the biomechanics of Sars-CoV-2, one thing is becoming increasingly clear: even “mild” cases can be more complicated, dangerous and harder to shake than many first thought.

Throughout the pandemic, a notion has persevered that people who have “mild” cases of Covid-19 and do not require an ICU stay or the use of a ventilator are spared from serious health repercussions. Just last week, Mike Pence, the US vice-president, claimed it’s “a good thing” that nearly half of the new Covid-19 cases surging in 16 states are young Americans, who are at less risk of becoming severely ill than their older counterparts. This kind of rhetoric would lead you to believe that the ordeal of “mildly infected” patients ends within two weeks of becoming ill, at which point they recover and everything goes back to normal.

While that may be the case for some people who get Covid-19, emerging medical research as well as anecdotal evidence from recovery support groups suggest that many survivors of “mild” Covid-19 are not so lucky. They experience lasting side-effects, and doctors are still trying to understand the ramifications.

Some of these side effects can be fatal. According to Dr Christopher Kellner, a professor of neurosurgery at Mount Sinai hospital in New York, “mild” cases of Covid-19 in which the patient was not hospitalized for the virus have been linked to blood clotting and severe strokes in people as young as 30. In May, Keller told Healthline that Mount Sinai had implemented a plan to give anticoagulant drugs to people with Covid-19 to prevent the strokes they were seeing in “younger patients with no or mild symptoms”.

Doctors now know that Covid-19 not only affects the lungs and blood, but kidneys, liver and brain – the latter potentially resulting in chronic fatigue and depression, among other symptoms. Although the virus is not yet old enough for long-term effects on those organs to be well understood, they may manifest regardless of whether a patient ever required hospitalization, hindering their recovery process.

Another troubling phenomenon now coming into focus is that of “long-haul” Covid-19 sufferers – people whose experience of the illness has lasted months. For a Dutch report published earlier this month (an excerpt is translated here) researchers surveyed 1,622 Covid-19 patients with an average age of 53, who reported a number of enduring symptoms, including intense fatigue (88%) persistent shortness of breath (75%) and chest pressure (45%). Ninety-one per cent of the patients weren’t hospitalized, suggesting they suffered these side-effects despite their cases of Covid-19 qualifying as “mild”. While 85% of the surveyed patients considered themselves generally healthy before having Covid-19, only 6% still did so one month or more after getting the virus.

After being diagnosed with Covid-19, 26-year-old Fiona Lowenstein experienced a long, difficult and nonlinear recovery first-hand. Lowenstein became sick on 17 March, and was briefly hospitalized for fever, cough and shortness of breath. Doctors advised she return to the hospital if those symptoms worsened – but something else happened instead. “I experienced this whole slew of new symptoms: sinus pain, sore throat, really severe gastrointestinal issues,” she told me. “I was having diarrhea every time I ate. I lost a lot of weight, which made me weak, a lot of fatigue, headaches, loss of sense of smell …”

By the time she felt mostly better, it was mid-May, although some of her symptoms still routinely re-emerge, she says.

“It’s almost like a blow to your ego to be in your 20s and healthy and active, and get hit with this thing and think you’re going to get better and you’re going to be OK. And then have it really not pan out that way,” says Lowenstein.

Unable to find information about what she was experiencing, and wondering if more people were going through a similarly prolonged recovery, Lowenstein created The Body Politic Slack-channel support group, a forum that now counts more than 5,600 members – most of whom were not hospitalized for their illness, yet have been feeling sick for months after their initial flu-like respiratory symptoms subsided. According to an internal survey within the group, members – the vast majority of whom are under 50 – have experienced symptoms including facial paralysis, seizures, hearing and vision loss, headaches, memory loss, diarrhea, serious weight loss and more.

“To me, and I think most people, the definition of ‘mild’, passed down from the WHO and other authorities, meant any case that didn’t require hospitalization at all, that anyone who wasn’t hospitalized was just going to have a small cold and could take care of it at home,” Hannah Davis, the author of a patient-led survey of Body Politic members, told me. “From my point of view, this has been a really harmful narrative and absolutely has misinformed the public. It both prohibits people from taking relevant information into account when deciding their personal risk levels, and it prevents the long-haulers from getting the help they need.”

At this stage, when medical professionals and the public alike are learning about Covid-19 as the pandemic unfolds, it’s important to keep in mind how little we truly know about this vastly complicated disease – and to listen to the experiences of survivors, especially those whose recoveries have been neither quick nor straightforward.

It may be reassuring to describe the majority of Covid-19 cases as “mild” – but perhaps that term isn’t as accurate as we hoped.

Conventional wisdom suggests that when a sickness is mild, it’s not too much to worry about. But if you’re taking comfort in World Health Organization reports that over 80% of global Covid-19 cases are mild or asymptomatic, think again. As virologists race to understand the biomechanics of Sars-CoV-2, one thing is becoming increasingly clear: even “mild” cases can be more complicated, dangerous and harder to shake than many first thought.

Throughout the pandemic, a notion has persevered that people who have “mild” cases of Covid-19 and do not require an ICU stay or the use of a ventilator are spared from serious health repercussions. Just last week, Mike Pence, the US vice-president, claimed it’s “a good thing” that nearly half of the new Covid-19 cases surging in 16 states are young Americans, who are at less risk of becoming severely ill than their older counterparts. This kind of rhetoric would lead you to believe that the ordeal of “mildly infected” patients ends within two weeks of becoming ill, at which point they recover and everything goes back to normal.

While that may be the case for some people who get Covid-19, emerging medical research as well as anecdotal evidence from recovery support groups suggest that many survivors of “mild” Covid-19 are not so lucky. They experience lasting side-effects, and doctors are still trying to understand the ramifications.

Some of these side effects can be fatal. According to Dr Christopher Kellner, a professor of neurosurgery at Mount Sinai hospital in New York, “mild” cases of Covid-19 in which the patient was not hospitalized for the virus have been linked to blood clotting and severe strokes in people as young as 30. In May, Keller told Healthline that Mount Sinai had implemented a plan to give anticoagulant drugs to people with Covid-19 to prevent the strokes they were seeing in “younger patients with no or mild symptoms”.

Doctors now know that Covid-19 not only affects the lungs and blood, but kidneys, liver and brain – the latter potentially resulting in chronic fatigue and depression, among other symptoms. Although the virus is not yet old enough for long-term effects on those organs to be well understood, they may manifest regardless of whether a patient ever required hospitalization, hindering their recovery process.

Another troubling phenomenon now coming into focus is that of “long-haul” Covid-19 sufferers – people whose experience of the illness has lasted months. For a Dutch report published earlier this month (an excerpt is translated here) researchers surveyed 1,622 Covid-19 patients with an average age of 53, who reported a number of enduring symptoms, including intense fatigue (88%) persistent shortness of breath (75%) and chest pressure (45%). Ninety-one per cent of the patients weren’t hospitalized, suggesting they suffered these side-effects despite their cases of Covid-19 qualifying as “mild”. While 85% of the surveyed patients considered themselves generally healthy before having Covid-19, only 6% still did so one month or more after getting the virus.

After being diagnosed with Covid-19, 26-year-old Fiona Lowenstein experienced a long, difficult and nonlinear recovery first-hand. Lowenstein became sick on 17 March, and was briefly hospitalized for fever, cough and shortness of breath. Doctors advised she return to the hospital if those symptoms worsened – but something else happened instead. “I experienced this whole slew of new symptoms: sinus pain, sore throat, really severe gastrointestinal issues,” she told me. “I was having diarrhea every time I ate. I lost a lot of weight, which made me weak, a lot of fatigue, headaches, loss of sense of smell …”

By the time she felt mostly better, it was mid-May, although some of her symptoms still routinely re-emerge, she says.

“It’s almost like a blow to your ego to be in your 20s and healthy and active, and get hit with this thing and think you’re going to get better and you’re going to be OK. And then have it really not pan out that way,” says Lowenstein.

Unable to find information about what she was experiencing, and wondering if more people were going through a similarly prolonged recovery, Lowenstein created The Body Politic Slack-channel support group, a forum that now counts more than 5,600 members – most of whom were not hospitalized for their illness, yet have been feeling sick for months after their initial flu-like respiratory symptoms subsided. According to an internal survey within the group, members – the vast majority of whom are under 50 – have experienced symptoms including facial paralysis, seizures, hearing and vision loss, headaches, memory loss, diarrhea, serious weight loss and more.

“To me, and I think most people, the definition of ‘mild’, passed down from the WHO and other authorities, meant any case that didn’t require hospitalization at all, that anyone who wasn’t hospitalized was just going to have a small cold and could take care of it at home,” Hannah Davis, the author of a patient-led survey of Body Politic members, told me. “From my point of view, this has been a really harmful narrative and absolutely has misinformed the public. It both prohibits people from taking relevant information into account when deciding their personal risk levels, and it prevents the long-haulers from getting the help they need.”

At this stage, when medical professionals and the public alike are learning about Covid-19 as the pandemic unfolds, it’s important to keep in mind how little we truly know about this vastly complicated disease – and to listen to the experiences of survivors, especially those whose recoveries have been neither quick nor straightforward.

It may be reassuring to describe the majority of Covid-19 cases as “mild” – but perhaps that term isn’t as accurate as we hoped.

Monday, 8 June 2020

We often accuse the right of distorting science. But the left changed the coronavirus narrative overnight

Racism is a health crisis. But poverty is too – yet progressives blithely accepted the costs of throwing millions of people like George Floyd out of work writes Thomas Chatterton Williams in The Guardian

‘Less than two weeks ago, the enlightened position was to exercise extreme caution. Many of us went further, taking to social media to shame others for insufficient social distancing.’ Photograph: Devon Ravine/AP

When I reflect back on the extraordinary year of 2020 – from, I hope, some safer, saner vantage – one of the two defining images in my mind will be the surreal figure of the Grim Reaper stalking the blazing Florida shoreline, scythe in hand, warning the sunbathing masses of imminent death and granting interviews to reporters. The other will be a prostrate George Floyd, whose excruciating Memorial Day execution sparked a global protest movement against racism and police violence.

Less than two weeks after Floyd’s killing, the American death toll from the novel coronavirus has surpassed 100,000. Rates of infection, domestically and worldwide, are rising. But one of the few things it seems possible to say without qualification is that the country has indeed reopened. For 13 days straight, in cities across the nation, tens of thousands of men and women have massed in tight-knit proximity, with and without personal protective equipment, often clashing with armed forces, chanting, singing and inevitably increasing the chances of the spread of contagion.

Scenes of outright pandemonium unfold daily. Anyone claiming to have a precise understanding of what is happening, and what the likely risks and consequences may be, should be regarded with the utmost skepticism. We are all living in a techno-dystopian fantasy, the internet-connected portals we rely on rendering the world in all its granular detail and absurdity like Borges’s Aleph. Yet we know very little about what it is we are watching.

I open my laptop and glimpse a rider on horseback galloping through the Chicago streets like Ras the Destroyer in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man; I scroll down further and find myself in Los Angeles, as the professional basketball star JR Smith pummels a scrawny anarchist who smashed his car window. I keep going and encounter a mixed group of business owners in Van Nuys risking their lives to defend their businesses from rampaging looters; the black community members trying to help them are swiftly rounded up by police officers who mistake them for the criminals. In Buffalo, a 75-year-old white man approaches a police phalanx and is immediately thrown to the pavement; blood spills from his ear as the police continue to march over him. Looming behind all of this chaos is a reality-TV president giddily tweeting exhortations to mass murder, only venturing out of his bunker to teargas peaceful protesters and stage propaganda pictures.

George Floyd wasn’t merely killed for being black – he was also killed for being poor

But this virus – for which we may never even find a vaccine – knows and respects none of this socio-political context. Its killing trajectory isn’t rational, emotional, or ethical – only mathematical. And just as two plus two is four, when a flood comes, low-lying areas get hit the hardest. Relatively poor, densely clustered populations with underlying conditions suffer disproportionately in any environment in which Covid-19 flourishes. Since the virus made landfall in the US, it has killed at least 20,000 black Americans.

After two and a half months of death, confinement, and unemployment figures dwarfing even the Great Depression, we have now entered the stage of competing urgencies where there are zero perfect options. Police brutality is a different if metaphorical epidemic in an America slouching toward authoritarianism. Catalyzed by the spectacle of Floyd’s reprehensible death, it is clear that the emergency in Minneapolis passes my own and many peoples’ threshold for justifying the risk of contagion.

But poverty is also a public health crisis. George Floyd wasn’t merely killed for being black – he was also killed for being poor. He died over a counterfeit banknote. Poverty destroys Americans every day by means of confrontations with the law, disease, pollution, violence and despair. Yet even as the coronavirus lockdown threw 40 million Americans out of work – including Floyd himself – many progressives accepted this calamity, sometimes with stunning blitheness, as the necessary cost of guarding against Covid-19.

The new, “correct” narrative about public health – that one kind of crisis has superseded the other – grows shakier as it spans out from Minnesota, across America to as far as London, Amsterdam and Paris – cities that have in recent days seen extraordinary manifestations of public solidarity against both American and local racism, with protesters in the many thousands flooding public spaces.

Consider France, where I live. The country has only just begun reopening after two solid months of one of the world’s severest national quarantines, and in the face of the world’s fifth-highest coronavirus body count. As recently as 11 May, it was mandatory here to carry a fully executed state-administered permission slip on one’s person in order to legally exercise or go shopping. The country has only just begun to flatten the curve of deaths – nearly 30,000 and counting – which have brought its economy to a standstill. Yet even here, in the time it takes to upload a black square to your Instagram profile, those of us who move in progressive circles now find ourselves under significant moral pressure to understand that social distancing is an issue of merely secondary importance.

This feels like gaslighting. Less than two weeks ago, the enlightened position in both Europe and America was to exercise nothing less than extreme caution. Many of us went much further, taking to social media to castigate others for insufficient social distancing or neglecting to wear masks or daring to believe they could maintain some semblance of a normal life during coronavirus. At the end of April, when the state of Georgia moved to end its lockdown, the Atlantic ran an article with the headline “Georgia’s Experiment in Human Sacrifice”. Two weeks ago we shamed people for being in the street; today we shame them for not being in the street.

As a result of lockdowns and quarantines, many millions of people around the world have lost their jobs, depleted their savings, missed funerals of loved ones, postponed cancer screenings and generally put their lives on hold for the indefinite future. They accepted these sacrifices as awful but necessary when confronted by an otherwise unstoppable virus. Was this or wasn’t this all an exercise in futility?

“The risks of congregating during a global pandemic shouldn’t keep people from protesting racism,” NPR suddenly tells us, citing a letter signed by dozens of American public health and disease experts. “White supremacy is a lethal public health issue that predates and contributes to Covid-19,” the letter said. One epidemiologist has gone even further, arguing that the public health risks of not protesting for an end to systemic racism “greatly exceed the harms of the virus”.

The climate-change-denying right is often ridiculed, correctly, for politicizing science. Yet the way the public health narrative around coronavirus has reversed itself overnight seems an awful lot like … politicizing science.

What are we to make of such whiplash-inducing messaging? Merely pointing out the inconsistency in such a polarized landscape feels like an act of heresy. But “‘Your gatherings are a threat, mine aren’t,’ is fundamentally illogical, no matter who says it or for what reason,” as the author of The Death of Expertise, Tom Nichols, put it. “We’ve been told for months to stay as isolated as humanely possible,” Suzy Khimm, an NBC reporter covering Covid-19, noted, but “some of the same public officials and epidemiologists are [now] saying it’s OK to go to mass gatherings – but only certain ones.”

Public health experts – as well as many mainstream commentators, plenty of whom in the beginning of the pandemic were already incoherent about the importance of face masks and stay-at-home orders – have hemorrhaged credibility and authority. This is not merely a short-term problem; it will constitute a crisis of trust going forward, when it may be all the more urgent to convince skeptical masses to submit to an unproven vaccine or to another round of crushing stay-at-home orders. Will anyone still listen?

Seventy years ago Camus showed us that the human condition itself amounts to a plague-like emergency – we are only ever managing our losses, striving for dignity in the process. Risk and safety are relative notions and never strictly objective. However, there is one inconvenient truth that cannot be disputed: more black Americans have been killed by three months of coronavirus than the number who have been killed by cops and vigilantes since the turn of the millennium. We may or may not be willing to accept that brutal calculus, but we are obligated, at the very least, to be honest.

When I reflect back on the extraordinary year of 2020 – from, I hope, some safer, saner vantage – one of the two defining images in my mind will be the surreal figure of the Grim Reaper stalking the blazing Florida shoreline, scythe in hand, warning the sunbathing masses of imminent death and granting interviews to reporters. The other will be a prostrate George Floyd, whose excruciating Memorial Day execution sparked a global protest movement against racism and police violence.

Less than two weeks after Floyd’s killing, the American death toll from the novel coronavirus has surpassed 100,000. Rates of infection, domestically and worldwide, are rising. But one of the few things it seems possible to say without qualification is that the country has indeed reopened. For 13 days straight, in cities across the nation, tens of thousands of men and women have massed in tight-knit proximity, with and without personal protective equipment, often clashing with armed forces, chanting, singing and inevitably increasing the chances of the spread of contagion.

Scenes of outright pandemonium unfold daily. Anyone claiming to have a precise understanding of what is happening, and what the likely risks and consequences may be, should be regarded with the utmost skepticism. We are all living in a techno-dystopian fantasy, the internet-connected portals we rely on rendering the world in all its granular detail and absurdity like Borges’s Aleph. Yet we know very little about what it is we are watching.

I open my laptop and glimpse a rider on horseback galloping through the Chicago streets like Ras the Destroyer in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man; I scroll down further and find myself in Los Angeles, as the professional basketball star JR Smith pummels a scrawny anarchist who smashed his car window. I keep going and encounter a mixed group of business owners in Van Nuys risking their lives to defend their businesses from rampaging looters; the black community members trying to help them are swiftly rounded up by police officers who mistake them for the criminals. In Buffalo, a 75-year-old white man approaches a police phalanx and is immediately thrown to the pavement; blood spills from his ear as the police continue to march over him. Looming behind all of this chaos is a reality-TV president giddily tweeting exhortations to mass murder, only venturing out of his bunker to teargas peaceful protesters and stage propaganda pictures.

George Floyd wasn’t merely killed for being black – he was also killed for being poor

But this virus – for which we may never even find a vaccine – knows and respects none of this socio-political context. Its killing trajectory isn’t rational, emotional, or ethical – only mathematical. And just as two plus two is four, when a flood comes, low-lying areas get hit the hardest. Relatively poor, densely clustered populations with underlying conditions suffer disproportionately in any environment in which Covid-19 flourishes. Since the virus made landfall in the US, it has killed at least 20,000 black Americans.

After two and a half months of death, confinement, and unemployment figures dwarfing even the Great Depression, we have now entered the stage of competing urgencies where there are zero perfect options. Police brutality is a different if metaphorical epidemic in an America slouching toward authoritarianism. Catalyzed by the spectacle of Floyd’s reprehensible death, it is clear that the emergency in Minneapolis passes my own and many peoples’ threshold for justifying the risk of contagion.

But poverty is also a public health crisis. George Floyd wasn’t merely killed for being black – he was also killed for being poor. He died over a counterfeit banknote. Poverty destroys Americans every day by means of confrontations with the law, disease, pollution, violence and despair. Yet even as the coronavirus lockdown threw 40 million Americans out of work – including Floyd himself – many progressives accepted this calamity, sometimes with stunning blitheness, as the necessary cost of guarding against Covid-19.

The new, “correct” narrative about public health – that one kind of crisis has superseded the other – grows shakier as it spans out from Minnesota, across America to as far as London, Amsterdam and Paris – cities that have in recent days seen extraordinary manifestations of public solidarity against both American and local racism, with protesters in the many thousands flooding public spaces.

Consider France, where I live. The country has only just begun reopening after two solid months of one of the world’s severest national quarantines, and in the face of the world’s fifth-highest coronavirus body count. As recently as 11 May, it was mandatory here to carry a fully executed state-administered permission slip on one’s person in order to legally exercise or go shopping. The country has only just begun to flatten the curve of deaths – nearly 30,000 and counting – which have brought its economy to a standstill. Yet even here, in the time it takes to upload a black square to your Instagram profile, those of us who move in progressive circles now find ourselves under significant moral pressure to understand that social distancing is an issue of merely secondary importance.

This feels like gaslighting. Less than two weeks ago, the enlightened position in both Europe and America was to exercise nothing less than extreme caution. Many of us went much further, taking to social media to castigate others for insufficient social distancing or neglecting to wear masks or daring to believe they could maintain some semblance of a normal life during coronavirus. At the end of April, when the state of Georgia moved to end its lockdown, the Atlantic ran an article with the headline “Georgia’s Experiment in Human Sacrifice”. Two weeks ago we shamed people for being in the street; today we shame them for not being in the street.

As a result of lockdowns and quarantines, many millions of people around the world have lost their jobs, depleted their savings, missed funerals of loved ones, postponed cancer screenings and generally put their lives on hold for the indefinite future. They accepted these sacrifices as awful but necessary when confronted by an otherwise unstoppable virus. Was this or wasn’t this all an exercise in futility?

“The risks of congregating during a global pandemic shouldn’t keep people from protesting racism,” NPR suddenly tells us, citing a letter signed by dozens of American public health and disease experts. “White supremacy is a lethal public health issue that predates and contributes to Covid-19,” the letter said. One epidemiologist has gone even further, arguing that the public health risks of not protesting for an end to systemic racism “greatly exceed the harms of the virus”.

The climate-change-denying right is often ridiculed, correctly, for politicizing science. Yet the way the public health narrative around coronavirus has reversed itself overnight seems an awful lot like … politicizing science.

What are we to make of such whiplash-inducing messaging? Merely pointing out the inconsistency in such a polarized landscape feels like an act of heresy. But “‘Your gatherings are a threat, mine aren’t,’ is fundamentally illogical, no matter who says it or for what reason,” as the author of The Death of Expertise, Tom Nichols, put it. “We’ve been told for months to stay as isolated as humanely possible,” Suzy Khimm, an NBC reporter covering Covid-19, noted, but “some of the same public officials and epidemiologists are [now] saying it’s OK to go to mass gatherings – but only certain ones.”

Public health experts – as well as many mainstream commentators, plenty of whom in the beginning of the pandemic were already incoherent about the importance of face masks and stay-at-home orders – have hemorrhaged credibility and authority. This is not merely a short-term problem; it will constitute a crisis of trust going forward, when it may be all the more urgent to convince skeptical masses to submit to an unproven vaccine or to another round of crushing stay-at-home orders. Will anyone still listen?

Seventy years ago Camus showed us that the human condition itself amounts to a plague-like emergency – we are only ever managing our losses, striving for dignity in the process. Risk and safety are relative notions and never strictly objective. However, there is one inconvenient truth that cannot be disputed: more black Americans have been killed by three months of coronavirus than the number who have been killed by cops and vigilantes since the turn of the millennium. We may or may not be willing to accept that brutal calculus, but we are obligated, at the very least, to be honest.

Sunday, 5 August 2018

Creating Routines for Self Improvement - Part 4 from Thinking in Bets

Extracts from Thinking in Bets by Annie Duke

In 2004 Phil Ivey destroyed a start studded table in a poker

tournament. After his win, during dinner, Ivey deconstructed every potential

playing error he thought he might have made on the way to victory, asking

others’ for their opinion about each strategic decision. A more run of the mill

player might have spent the time talking about how great they played, relishing

the victory. Not Ivey. For him, the opportunity to learn from his mistakes was

much more important than treating the dinner as a self-satisfying celebration.

Ivey, clearly has different habits than most players and most

people in any endeavor in how he fields his results. Habits operate in a

neurological loop consisting of three parts: the cue, the routine and the

reward. In cricket the cue might be a won game, the routine taking credit for

it and the reward is a boost to our ego. To change a habit you must keep the

old cue, and deliver the old reward but insert a new routine.

What we do: When

we have a good outcome, it cues the routine of crediting the result to our

awesome decision-making, delivering the reward of a positive update to our

self-narrative. A bad outcome cues the routine of off-loading responsibility

for the result, delivering the reward of avoiding a negative self-narrative

update. With the same cues, we flip the routine for the outcomes of our peers,

but the reward is the same – feeling good about ourselves.

The good news is that we can work to change this habit of

mind by substituting what makes us feel good. The golden rule of habit change

says we don’t have to give up the reward of a positive update to our narrative,

nor should we.

We can work to get the reward of feeling good about ourselves

from being a good credit-giver, a good mistake-admitter, a good finder of

mistakes in good outcomes, a good learner and a good decision maker. Instead of

feeling bad when we have to admit a mistake, what if the bad feeling came from

the thought that we might be missing a learning opportunity just to avoid

blame? Or that we might be basking in the credit of a good result instead of recognizing,

like Ivey, where we could have done better? If we put in the work to practice

this routine, we can field more of our outcomes in an open minded, more

objective way, motivated by accuracy and truth-seeking to drive learning. The

habit of mind will change, and our decision making will better align with our

long term goals.

When we look at the people performing at the highest level

of their chosen field, we find they have developed habits around accurate

self-critique.

Changing the routine is hard and takes work.

Monday, 16 July 2018

Wednesday, 23 May 2018

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)