'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label false. Show all posts

Showing posts with label false. Show all posts

Monday, 13 September 2021

Saturday, 24 April 2021

Thursday, 14 May 2020

Saturday, 5 May 2018

Is Marx still relevant 200 years later?

Amartya Sen in The Indian Express

How should we think about Karl Marx on his 200th birthday? His big influence on the politics of the world is universally acknowledged, though people would differ on how good or bad that influence has been. But going beyond that, there can be little doubt that the intellectual world has been transformed by the reflective departures Marx generated, from class analysis as an essential part of social understanding, to the explication of the profound contrast between needs and hard work as conflicting foundations of people’s moral entitlements. Some of the influences have been so pervasive, with such strong impact on the concepts and connection we look for in our day-to-day analysis, that we may not be fully aware where the influences came from. In reading some classic works of Marx, we are often placed in the uncomfortable position of the theatre-goer who loved Hamlet as a play, but wondered why it was so full of quotations.

Marxian analysis remains important today not just because of Marx’s own original work, but also because of the extraordinary contributions made in that tradition by many leading historians, social scientists and creative artists — from Antonio Gramsci, Rosa Luxemburg, Jean-Paul Sartre and Bertolt Brecht to Piero Sraffa, Maurice Dobb and Eric Hobsbawm (to mention just a few names). We do not have to be a Marxist to make use of the richness of Marx’s insights — just as one does not have to be an Aristotelian to learn from Aristotle.

There are ideas in Marx’s corpus of work that remain under-explored. I would place among the relatively neglected ideas Marx’s highly original concept of “objective illusion,” and related to that, his discussion of “false consciousness”. An objective illusion may arise from what we can see from our particular position — how things look from there (no matter how misleading). Consider the relative sizes of the sun and the moon, and the fact that from the earth they look to be about the same size (Satyajit Ray offered some interesting conversations on this phenomenon in his film, Agantuk). But to conclude from this observation that the sun and the moon are in fact of the same size in terms of mass or volume would be mistaken, and yet to deny that they do look to be about the same size from the earth would be a mistake too. Marx’s investigation of objective illusion — of “the outer form of things” — is a pioneering contribution to understanding the implications of positional dependence of observations.

The phenomenon of objective illusion helps to explain the widespread tendency of workers in an exploitative society to fail to see that there is any exploitation going on — an example that Marx did much to investigate, in the form of “false consciousness”. The idea can have many applications going beyond Marx’s own use of it. Powerful use can be made of the notion of objective illusion to understand, for example, how women, and indeed men, in strongly sexist societies may not see clearly enough — in the absence of informed political agitation — that there are huge elements of gender inequality in what look like family-oriented just societies, as bastions of role-based fairness.

There is, however, a danger in seeing Marx in narrowly formulaic terms — for example, in seeing him as a “materialist” who allegedly understood the world in terms of the importance of material conditions, denying the significance of ideas and beliefs. This is not only a serious misreading of Marx, who emphasised two-way relations between ideas and material conditions, but also a seriously missed opportunity to see the far-reaching role of ideas on which Marx threw such important light.

Let me illustrate the point with a debate on the discipline of historical explanation that was quite widespread in our own time. In one of Eric Hobsbawm’s lesser known essays, called “Where Are British Historians Going?”, published in the Marxist Quarterly in 1955, he discussed how the Marxist pointer to the two-way relationship between ideas and material conditions offers very different lessons in the contemporary world than it had in the intellectual world that Marx himself saw around him, where the prevailing focus — for example by Hegel and Hegelians — was very much on highlighting the influence of ideas on material conditions.

In contrast, the tendency of dominant schools of history in the mid-twentieth century — Hobsbawm cited here the hugely influential historical works of Lewis Bernstein Namier — had come to embrace a type of materialism that saw human action as being almost entirely motivated by a simple kind of material interest, in particular narrowly defined self-interest. Given this completely different kind of bias (very far removed from the idealist traditions of Hegel and other influential thinkers in Marx’s own time), Hobsbawm argued that a balanced two-way view must demand that analysis in Marxian lines today must particularly emphasise the importance of ideas and their influence on material conditions.

For example, it is crucial to recognise that Edmund Burke’s hugely influential criticism of Warren Hastings’s misbehaviour in India — in the famous Impeachment hearings — was directly related to Burke’s strongly held ideas of justice and fairness, whereas the self-interest-obsessed materialist historians, such as Namier, saw no more in Burke’s discontent than the influence of his [Burke’s] profit-seeking concerns which had suffered because of the policies pursued by Hastings. The overreliance on materialism — in fact of a particularly narrow kind — needed serious correction, argued Hobsbawm: “In the pre-Namier days, Marxists regarded it as one of their chief historical duties to draw attention to the material basis of politics. But since bourgeois historians have adopted what is a particular form of vulgar materialism, Marxists had to remind them that history is the struggle of men for ideas, as well as a reflection of their material environment. Mr Trevor-Roper [a famous right-wing historian] is not merely mistaken in believing that the English Revolution was the reflection of the declining fortunes of country gentlemen, but also in his belief that Puritanism was simply a reflection of their impending bankruptcies.”

To Hobsbawm’s critique, it could be added that the so-called “rational choice theory” (so dominant in recent years in large parts of mainstream economics and political analysis) thrives on a single-minded focus on self-interest as the sole human motivation, thereby missing comprehensively the balance that Marx had argued for. A rational choice theorist can, in fact, learn a great deal from reading Marx’s Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts and The German Ideology. While this would be a very different lesson from what Marx wanted Hegelians to consider, a commitment to doing justice to the two-way relations characterises both parts of Marx’s capacious pedagogy. What has to be avoided is the narrowing of Marx’s thoughts through simple formulas respectfully distributed in his name.

In remembering Marx on his 200th birthday, we not only celebrate a great intellectual, but also one whose critical analyses and investigations have many insights to offer to us today. Paying attention to Marx may be more important than paying him respect.

-------

Slavoj Zizek in The Independent

There is a delicious old Soviet joke about Radio Yerevan: a listener asks: “Is it true that Rabinovitch won a new car in the lottery?”, and the radio presenter answers: “In principle yes, it’s true, only it wasn’t a new car but an old bicycle, and he didn’t win it but it was stolen from him.”

Does exactly the same not hold for Marx’s legacy today? Let’s ask Radio Yerevan: “Is Marx’s theory still relevant today?” We can guess the answer: in principle yes, he describes wonderfully the mad dance of capitalist dynamics which only reached its peak today, more than a century and a half later, but… Gerald A Cohen enumerated the four features of the classic Marxist notion of the working class: (1) it constitutes the majority of society; (2) it produces the wealth of society; (3) it consists of the exploited members of society; and (4) its members are the needy people in society. When these four features are combined, they generate two further features: (5) the working class has nothing to lose from revolution; and (6) it can and will engage in a revolutionary transformation of society.

None of the first four features applies to today’s working class, which is why features (5) and (6) cannot be generated. Even if some of the features continue to apply to parts of today’s society, they are no longer united in a single agent: the needy people in society are no longer the workers, and so on.

But let’s dig into this question of relevance and appropriateness further. Not only is Marx’s critique of political economy and his outline of the capitalist dynamics still fully relevant, but one could even take a step further and claim that it is only today, with global capitalism, that it is fully relevant.

However, at the moment of triumph is one of defeat. After overcoming external obstacles the new threat comes from within. In other words, Marx was not simply wrong, he was often right – but more literally than he himself expected to be.

For example, Marx couldn’t have imagined that the capitalist dynamics of dissolving all particular identities would translate into ethnic identities as well. Today’s celebration of “minorities” and “marginals” is the predominant majority position – alt-rightists who complain about the terror of “political correctness” take advantage of this by presenting themselves as protectors of an endangered minority, attempting to mirror campaigns on the other side.

And then there’s the case of “commodity fetishism”. Recall the classic joke about a man who believes himself to be a grain of seed and is taken to a mental institution where the doctors do their best to finally convince him that he is not a grain but a man. When he is cured (convinced that he is not a grain of seed but a man) and allowed to leave the hospital, he immediately comes back trembling. There is a chicken outside the door and he is afraid that it will eat him.

“Dear fellow,” says his doctor, “you know very well that you are not a grain of seed but a man.”

“Of course I know that,” replies the patient, “but does the chicken know it?”

So how does this apply to the notion of commodity fetishism? Note the very beginning of the subchapter on commodity fetishism in Marx’s Das Kapital: “A commodity appears at first sight an extremely obvious, trivial thing. But its analysis brings out that it is a very strange thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties.”

Commodity fetishism (our belief that commodities are magic objects, endowed with an inherent metaphysical power) is not located in our mind, in the way we (mis)perceive reality, but in our social reality itself. We may know the truth, but we act as if we don’t know it – in our real life, we act like the chicken from the joke.

Niels Bohr, who already gave the right answer to Einstein’s “God doesn’t play dice“(“Don’t tell God what to do!”), also provided the perfect example of how a fetishist disavowal of belief works. Seeing a horseshoe on his door, a surprised visitor commented that he didn’t think Bohr believed superstitious ideas about horseshoes bringing good luck to people. Bohr snapped back: “I also do not believe in it; I have it there because I was told that it works whether one believes in it or not!”

This is how ideology works in our cynical era: we don’t have to believe in it. Nobody takes democracy or justice seriously, we are all aware of their corruption, but we practice them – in other words, we display our belief in them – because we assume they work even if we do not believe in them.

With regard to religion, we no longer “really believe”, we just follow (some of the) religious rituals and mores as part of the respect for the “lifestyle” of the community to which we belong (non-believing Jews obeying kosher rules “out of respect for tradition”, for example).

“I do not really believe in it, it is just part of my culture” seems to be the predominant mode of the displaced belief, characteristic of our times. “Culture” is the name for all those things we practice without really believing in them, without taking them quite seriously.

This is why we dismiss fundamentalist believers as “barbarians” or “primitive”, as anti-cultural, as a threat to culture – they dare to take seriously their beliefs. The cynical era in which we live would have no surprises for Marx.

Marx’s theories are thus not simply alive: Marx is a ghost who continues to haunt us – and the only way to keep him alive is to focus on those of his insights which are today more true than in his own time.

How should we think about Karl Marx on his 200th birthday? His big influence on the politics of the world is universally acknowledged, though people would differ on how good or bad that influence has been. But going beyond that, there can be little doubt that the intellectual world has been transformed by the reflective departures Marx generated, from class analysis as an essential part of social understanding, to the explication of the profound contrast between needs and hard work as conflicting foundations of people’s moral entitlements. Some of the influences have been so pervasive, with such strong impact on the concepts and connection we look for in our day-to-day analysis, that we may not be fully aware where the influences came from. In reading some classic works of Marx, we are often placed in the uncomfortable position of the theatre-goer who loved Hamlet as a play, but wondered why it was so full of quotations.

Marxian analysis remains important today not just because of Marx’s own original work, but also because of the extraordinary contributions made in that tradition by many leading historians, social scientists and creative artists — from Antonio Gramsci, Rosa Luxemburg, Jean-Paul Sartre and Bertolt Brecht to Piero Sraffa, Maurice Dobb and Eric Hobsbawm (to mention just a few names). We do not have to be a Marxist to make use of the richness of Marx’s insights — just as one does not have to be an Aristotelian to learn from Aristotle.

There are ideas in Marx’s corpus of work that remain under-explored. I would place among the relatively neglected ideas Marx’s highly original concept of “objective illusion,” and related to that, his discussion of “false consciousness”. An objective illusion may arise from what we can see from our particular position — how things look from there (no matter how misleading). Consider the relative sizes of the sun and the moon, and the fact that from the earth they look to be about the same size (Satyajit Ray offered some interesting conversations on this phenomenon in his film, Agantuk). But to conclude from this observation that the sun and the moon are in fact of the same size in terms of mass or volume would be mistaken, and yet to deny that they do look to be about the same size from the earth would be a mistake too. Marx’s investigation of objective illusion — of “the outer form of things” — is a pioneering contribution to understanding the implications of positional dependence of observations.

The phenomenon of objective illusion helps to explain the widespread tendency of workers in an exploitative society to fail to see that there is any exploitation going on — an example that Marx did much to investigate, in the form of “false consciousness”. The idea can have many applications going beyond Marx’s own use of it. Powerful use can be made of the notion of objective illusion to understand, for example, how women, and indeed men, in strongly sexist societies may not see clearly enough — in the absence of informed political agitation — that there are huge elements of gender inequality in what look like family-oriented just societies, as bastions of role-based fairness.

There is, however, a danger in seeing Marx in narrowly formulaic terms — for example, in seeing him as a “materialist” who allegedly understood the world in terms of the importance of material conditions, denying the significance of ideas and beliefs. This is not only a serious misreading of Marx, who emphasised two-way relations between ideas and material conditions, but also a seriously missed opportunity to see the far-reaching role of ideas on which Marx threw such important light.

Let me illustrate the point with a debate on the discipline of historical explanation that was quite widespread in our own time. In one of Eric Hobsbawm’s lesser known essays, called “Where Are British Historians Going?”, published in the Marxist Quarterly in 1955, he discussed how the Marxist pointer to the two-way relationship between ideas and material conditions offers very different lessons in the contemporary world than it had in the intellectual world that Marx himself saw around him, where the prevailing focus — for example by Hegel and Hegelians — was very much on highlighting the influence of ideas on material conditions.

In contrast, the tendency of dominant schools of history in the mid-twentieth century — Hobsbawm cited here the hugely influential historical works of Lewis Bernstein Namier — had come to embrace a type of materialism that saw human action as being almost entirely motivated by a simple kind of material interest, in particular narrowly defined self-interest. Given this completely different kind of bias (very far removed from the idealist traditions of Hegel and other influential thinkers in Marx’s own time), Hobsbawm argued that a balanced two-way view must demand that analysis in Marxian lines today must particularly emphasise the importance of ideas and their influence on material conditions.

For example, it is crucial to recognise that Edmund Burke’s hugely influential criticism of Warren Hastings’s misbehaviour in India — in the famous Impeachment hearings — was directly related to Burke’s strongly held ideas of justice and fairness, whereas the self-interest-obsessed materialist historians, such as Namier, saw no more in Burke’s discontent than the influence of his [Burke’s] profit-seeking concerns which had suffered because of the policies pursued by Hastings. The overreliance on materialism — in fact of a particularly narrow kind — needed serious correction, argued Hobsbawm: “In the pre-Namier days, Marxists regarded it as one of their chief historical duties to draw attention to the material basis of politics. But since bourgeois historians have adopted what is a particular form of vulgar materialism, Marxists had to remind them that history is the struggle of men for ideas, as well as a reflection of their material environment. Mr Trevor-Roper [a famous right-wing historian] is not merely mistaken in believing that the English Revolution was the reflection of the declining fortunes of country gentlemen, but also in his belief that Puritanism was simply a reflection of their impending bankruptcies.”

To Hobsbawm’s critique, it could be added that the so-called “rational choice theory” (so dominant in recent years in large parts of mainstream economics and political analysis) thrives on a single-minded focus on self-interest as the sole human motivation, thereby missing comprehensively the balance that Marx had argued for. A rational choice theorist can, in fact, learn a great deal from reading Marx’s Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts and The German Ideology. While this would be a very different lesson from what Marx wanted Hegelians to consider, a commitment to doing justice to the two-way relations characterises both parts of Marx’s capacious pedagogy. What has to be avoided is the narrowing of Marx’s thoughts through simple formulas respectfully distributed in his name.

In remembering Marx on his 200th birthday, we not only celebrate a great intellectual, but also one whose critical analyses and investigations have many insights to offer to us today. Paying attention to Marx may be more important than paying him respect.

-------

Slavoj Zizek in The Independent

There is a delicious old Soviet joke about Radio Yerevan: a listener asks: “Is it true that Rabinovitch won a new car in the lottery?”, and the radio presenter answers: “In principle yes, it’s true, only it wasn’t a new car but an old bicycle, and he didn’t win it but it was stolen from him.”

Does exactly the same not hold for Marx’s legacy today? Let’s ask Radio Yerevan: “Is Marx’s theory still relevant today?” We can guess the answer: in principle yes, he describes wonderfully the mad dance of capitalist dynamics which only reached its peak today, more than a century and a half later, but… Gerald A Cohen enumerated the four features of the classic Marxist notion of the working class: (1) it constitutes the majority of society; (2) it produces the wealth of society; (3) it consists of the exploited members of society; and (4) its members are the needy people in society. When these four features are combined, they generate two further features: (5) the working class has nothing to lose from revolution; and (6) it can and will engage in a revolutionary transformation of society.

None of the first four features applies to today’s working class, which is why features (5) and (6) cannot be generated. Even if some of the features continue to apply to parts of today’s society, they are no longer united in a single agent: the needy people in society are no longer the workers, and so on.

But let’s dig into this question of relevance and appropriateness further. Not only is Marx’s critique of political economy and his outline of the capitalist dynamics still fully relevant, but one could even take a step further and claim that it is only today, with global capitalism, that it is fully relevant.

However, at the moment of triumph is one of defeat. After overcoming external obstacles the new threat comes from within. In other words, Marx was not simply wrong, he was often right – but more literally than he himself expected to be.

For example, Marx couldn’t have imagined that the capitalist dynamics of dissolving all particular identities would translate into ethnic identities as well. Today’s celebration of “minorities” and “marginals” is the predominant majority position – alt-rightists who complain about the terror of “political correctness” take advantage of this by presenting themselves as protectors of an endangered minority, attempting to mirror campaigns on the other side.

And then there’s the case of “commodity fetishism”. Recall the classic joke about a man who believes himself to be a grain of seed and is taken to a mental institution where the doctors do their best to finally convince him that he is not a grain but a man. When he is cured (convinced that he is not a grain of seed but a man) and allowed to leave the hospital, he immediately comes back trembling. There is a chicken outside the door and he is afraid that it will eat him.

“Dear fellow,” says his doctor, “you know very well that you are not a grain of seed but a man.”

“Of course I know that,” replies the patient, “but does the chicken know it?”

So how does this apply to the notion of commodity fetishism? Note the very beginning of the subchapter on commodity fetishism in Marx’s Das Kapital: “A commodity appears at first sight an extremely obvious, trivial thing. But its analysis brings out that it is a very strange thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties.”

Commodity fetishism (our belief that commodities are magic objects, endowed with an inherent metaphysical power) is not located in our mind, in the way we (mis)perceive reality, but in our social reality itself. We may know the truth, but we act as if we don’t know it – in our real life, we act like the chicken from the joke.

Niels Bohr, who already gave the right answer to Einstein’s “God doesn’t play dice“(“Don’t tell God what to do!”), also provided the perfect example of how a fetishist disavowal of belief works. Seeing a horseshoe on his door, a surprised visitor commented that he didn’t think Bohr believed superstitious ideas about horseshoes bringing good luck to people. Bohr snapped back: “I also do not believe in it; I have it there because I was told that it works whether one believes in it or not!”

This is how ideology works in our cynical era: we don’t have to believe in it. Nobody takes democracy or justice seriously, we are all aware of their corruption, but we practice them – in other words, we display our belief in them – because we assume they work even if we do not believe in them.

With regard to religion, we no longer “really believe”, we just follow (some of the) religious rituals and mores as part of the respect for the “lifestyle” of the community to which we belong (non-believing Jews obeying kosher rules “out of respect for tradition”, for example).

“I do not really believe in it, it is just part of my culture” seems to be the predominant mode of the displaced belief, characteristic of our times. “Culture” is the name for all those things we practice without really believing in them, without taking them quite seriously.

This is why we dismiss fundamentalist believers as “barbarians” or “primitive”, as anti-cultural, as a threat to culture – they dare to take seriously their beliefs. The cynical era in which we live would have no surprises for Marx.

Marx’s theories are thus not simply alive: Marx is a ghost who continues to haunt us – and the only way to keep him alive is to focus on those of his insights which are today more true than in his own time.

Tuesday, 6 February 2018

The myth of post-truth

The assumption is that my truth is as good as your truth, and hence all truths are immaterial and irrelevant. Such extreme relativism is a problem

Tabish Khair in The Hindu

It has been remarked that ‘post-truth’ is very different from similar terms with the prefix post-, such as postcolonialism and postmodernism. No one who uses postcolonialism or postmodernism argues that colonialism and modernism are no longer relevant. However, the assumption behind ‘post-truth’ is that the concept of truth is no longer relevant.

Why is there no post-falsehood?

The philosophical (or, in my view, anti-philosophical) aspects of ‘post-truth’ cannot be covered in a column — they would require a voluminous thesis. However, it is worth asking: why do we not talk of ‘post-falsehood’? After all, the opposite of truth is not post-truth but falsehood. In that case, if we can have an age of post-truth, we should be able to talk of an age of post-falsehood too. Having gone past truth, we should also be able to go past its opposite: falsehood. This, however, is not the case.

Partly, this has to do with the nature of truth and how we have understood it across cultures. Truth is seen as singular and fixed: it is generally felt that there can be only one truth, while there may be many falsehoods. Hence, we feel that to go past truth is to go past a singularity, but to go past falsehood might well mean to choose among multiple falsehoods.

There is another reason why ‘post-falsehood’ does not exist: strangely enough, it would come to mean ‘truth’. We instinctively feel that to go beyond generic falsehood is also to reach truth. That is because the positivity of truth cannot exist without the negativity of falsehood. The essential lie of ‘post-truth’ is exactly this: it is supposed not to suggest falsehood. But if there is no falsehood on the other side of truth, then there is no truth either. ‘Post-truth’ dismisses the very possibility of truth — and, by that act, it dismisses the existence of falsehood.

In short, it dismisses critical and scientific thinking, which are based not on eternal truth, which is religion’s penchant, but on a methodical and endless elimination of falsehoods. This is essentially what Karl Popper meant when he stressed that a scientific statement needs to be falsifiable.

It is nevertheless interesting to stand the matter on its head and pose this question: if we cannot talk of ‘post-falsehood’, surely the fact that we are talking of ‘post-truth’ means that there is actually a difference between truth and falsehood? And if that is the case, then, by definition, we can never have an age of ‘post-truth’ — in the sense of equating truths and falsehoods.

Truths are contextual

On the other hand, belief in a singular, unchanging truth is also what has led to the mistaken notion of an age of ‘post-truth’. That is so because the idea of one eternally fixed truth has been radically shaken over the past few centuries in different ways, most of which do not lead to extreme relativism but instead to a kind of contextualisation. However, this necessary shaking of given and fixed truths can be and is often converted into an extreme relativism by the loudly ignorant — a relativism in which all truths seem relative to you as an observer, and not to the complex context of the observation. This slippage inevitably leads to talk of post-truth, especially in fields outside the hard sciences.

In fact, truths are contextual — not relativist — in hard science too: the ‘truth’ of subatomic particles exists in the context of atoms, and the ‘truth’ of planetary systems in our universe exists in that context. These are not necessarily exclusive contexts, but only a seriously confused student would expect the rules that obtain within an atom to be the same as the rules that apply to our planetary system. This is what I mean by contextualisation.

Relativism, on the other hand, or at least extreme relativism (for many versions of what is called ‘relativism’ are basically contextualisation), extracts the observer from the context and makes the observer’s version paramount.

This is what lies at the core of ‘post-truth.’ The assumption is that my truth is as good as your truth, and hence all truths are immaterial and irrelevant. Need I note the problem of such extreme relativism, for it puts the observer outside a context, a context that can be and should be used to determine the ‘truth’ of his or her observations. Truths might not be eternally fixed, but we do get closer to what is true by comparing and contrasting our versions of it: to you it might be superman, to me it is a bird, but enough and better sightings will ascertain that it is actually a plane.

Hence, while one can argue about the details of evolution, the fact that both human beings and apes evolved from a common ancestor is more true than the claim that human beings were directly handcrafted by a god. There is overwhelming evidence of the former, and it can be dismissed only by stubborn acts of belief (or disbelief).

However, one should not oppose the myth of post-truth by returning to older and faulty myths of fixed, eternal truths. This too would block the necessary and fledgling project of critical inquiry. We need to maintain a balance between the dismissal of the difference between truth and falsehood and blind acceptance of given truths. The future of humanity depends on our precarious ability to maintain this delicate balance.

Tabish Khair in The Hindu

It has been remarked that ‘post-truth’ is very different from similar terms with the prefix post-, such as postcolonialism and postmodernism. No one who uses postcolonialism or postmodernism argues that colonialism and modernism are no longer relevant. However, the assumption behind ‘post-truth’ is that the concept of truth is no longer relevant.

Why is there no post-falsehood?

The philosophical (or, in my view, anti-philosophical) aspects of ‘post-truth’ cannot be covered in a column — they would require a voluminous thesis. However, it is worth asking: why do we not talk of ‘post-falsehood’? After all, the opposite of truth is not post-truth but falsehood. In that case, if we can have an age of post-truth, we should be able to talk of an age of post-falsehood too. Having gone past truth, we should also be able to go past its opposite: falsehood. This, however, is not the case.

Partly, this has to do with the nature of truth and how we have understood it across cultures. Truth is seen as singular and fixed: it is generally felt that there can be only one truth, while there may be many falsehoods. Hence, we feel that to go past truth is to go past a singularity, but to go past falsehood might well mean to choose among multiple falsehoods.

There is another reason why ‘post-falsehood’ does not exist: strangely enough, it would come to mean ‘truth’. We instinctively feel that to go beyond generic falsehood is also to reach truth. That is because the positivity of truth cannot exist without the negativity of falsehood. The essential lie of ‘post-truth’ is exactly this: it is supposed not to suggest falsehood. But if there is no falsehood on the other side of truth, then there is no truth either. ‘Post-truth’ dismisses the very possibility of truth — and, by that act, it dismisses the existence of falsehood.

In short, it dismisses critical and scientific thinking, which are based not on eternal truth, which is religion’s penchant, but on a methodical and endless elimination of falsehoods. This is essentially what Karl Popper meant when he stressed that a scientific statement needs to be falsifiable.

It is nevertheless interesting to stand the matter on its head and pose this question: if we cannot talk of ‘post-falsehood’, surely the fact that we are talking of ‘post-truth’ means that there is actually a difference between truth and falsehood? And if that is the case, then, by definition, we can never have an age of ‘post-truth’ — in the sense of equating truths and falsehoods.

Truths are contextual

On the other hand, belief in a singular, unchanging truth is also what has led to the mistaken notion of an age of ‘post-truth’. That is so because the idea of one eternally fixed truth has been radically shaken over the past few centuries in different ways, most of which do not lead to extreme relativism but instead to a kind of contextualisation. However, this necessary shaking of given and fixed truths can be and is often converted into an extreme relativism by the loudly ignorant — a relativism in which all truths seem relative to you as an observer, and not to the complex context of the observation. This slippage inevitably leads to talk of post-truth, especially in fields outside the hard sciences.

In fact, truths are contextual — not relativist — in hard science too: the ‘truth’ of subatomic particles exists in the context of atoms, and the ‘truth’ of planetary systems in our universe exists in that context. These are not necessarily exclusive contexts, but only a seriously confused student would expect the rules that obtain within an atom to be the same as the rules that apply to our planetary system. This is what I mean by contextualisation.

Relativism, on the other hand, or at least extreme relativism (for many versions of what is called ‘relativism’ are basically contextualisation), extracts the observer from the context and makes the observer’s version paramount.

This is what lies at the core of ‘post-truth.’ The assumption is that my truth is as good as your truth, and hence all truths are immaterial and irrelevant. Need I note the problem of such extreme relativism, for it puts the observer outside a context, a context that can be and should be used to determine the ‘truth’ of his or her observations. Truths might not be eternally fixed, but we do get closer to what is true by comparing and contrasting our versions of it: to you it might be superman, to me it is a bird, but enough and better sightings will ascertain that it is actually a plane.

Hence, while one can argue about the details of evolution, the fact that both human beings and apes evolved from a common ancestor is more true than the claim that human beings were directly handcrafted by a god. There is overwhelming evidence of the former, and it can be dismissed only by stubborn acts of belief (or disbelief).

However, one should not oppose the myth of post-truth by returning to older and faulty myths of fixed, eternal truths. This too would block the necessary and fledgling project of critical inquiry. We need to maintain a balance between the dismissal of the difference between truth and falsehood and blind acceptance of given truths. The future of humanity depends on our precarious ability to maintain this delicate balance.

Monday, 25 September 2017

Dead Cats - Fatal attraction of fake facts sours political debate

Tim Harford in The Financial Times

He did it again: Boris Johnson, UK foreign secretary, exhumed the old referendum-campaign lie that leaving the EU would free up £350m a week for the National Health Service. I think we can skip the well-worn details, because while the claim is misleading, its main purpose is not to mislead but to distract. The growing popularity of this tactic should alarm anyone who thinks that the truth still matters.

He did it again: Boris Johnson, UK foreign secretary, exhumed the old referendum-campaign lie that leaving the EU would free up £350m a week for the National Health Service. I think we can skip the well-worn details, because while the claim is misleading, its main purpose is not to mislead but to distract. The growing popularity of this tactic should alarm anyone who thinks that the truth still matters.

You don’t need to take my word for it that distraction is the goal. A few years ago, a cynical commentator described the “dead cat” strategy, to be deployed when losing an argument at a dinner party: throw a dead cat on the table. The awkward argument will instantly cease, and everyone will start losing their minds about the cat. The cynic’s name was Boris Johnson.

The tactic worked perfectly in the Brexit referendum campaign. Instead of a discussion of the merits and disadvantages of EU membership, we had a frenzied dead-cat debate over the true scale of EU membership fees. Without the steady repetition of a demonstrably false claim, the debate would have run out of oxygen and we might have enjoyed a discussion of the issues instead.

My point is not to refight the referendum campaign. (Mr Johnson would like to, which itself is telling.) There’s more at stake here than Brexit: bold lies have become the dead cat of modern politics on both sides of the Atlantic. Too many politicians have discovered the attractions of the flamboyant falsehood — and why not? The most prominent of them sits in the White House. Dramatic lies do not always persuade, but they do tend to change the subject — and that is often enough.

It is hard to overstate how corrosive this development is. Reasoned conversation becomes impossible; the debaters hardly have time to clear their throats before a fly-blown moggie hits the table with a rancid thud.

Nor is it easy to neutralise a big, politicised lie. Trustworthy nerds can refute it, of course: the fact-checkers, the independent think-tanks, or statutory bodies such as the UK Statistics Authority. But a politician who is unafraid to lie is also unafraid to smear these organisations with claims of bias or corruption — and then one problem has become two. The Statistics Authority and other watchdogs need to guard jealously their reputation for truthfulness; the politicians they contradict often have no such reputation to worry about.

Researchers have been studying the problem for years, after noting how easily charlatans could debase the discussion of smoking, vaccination and climate change. A good starting point is The Debunking Handbook by John Cook and Stephan Lewandowsky, which summarises a dispiriting set of discoveries.

One problem that fact-checkers face is the “familiarity effect”: the endless arguments over the £350m-a-week lie (or Barack Obama’s birthplace, or the number of New Jersey residents who celebrated the destruction of the World Trade Center) is that the very process of rebutting the falsehood ensures that it is repeated over and over again. Even someone who accepts that the lie is a lie would find it much easier to remember than the truth.

A second obstacle is the “backfire effect”. My son is due to get a flu vaccine this week, and some parents at his school are concerned that the flu vaccine may cause flu. It doesn’t. But in explaining that I risk triggering other concerns: who can trust Big Pharma these days? Shouldn’t kids be a bit older before being exposed to these strange chemicals? Some (not all) studies suggest that the process of refuting the narrow concern can actually harden the broader worldview behind it.

Dan Kahan, professor of law and psychology at Yale, points out that issues such as vaccination or climate change — or for that matter, the independence of the UK Statistics Authority — do not become politicised by accident. They are dragged into the realm of polarised politics because it suits some political entrepreneur to do so. For a fleeting partisan advantage, Donald Trump has falsely claimed that vaccines cause autism. Children will die as a result. And once the intellectual environment has become polluted and polarised in this way, it’s extraordinarily difficult to draw the poison out again.

This is a damaging game indeed. All of us tend to think tribally about politics: we absorb the opinions of those around us. But tribal thinking pushes us to be not only a Republican but also a Republican and a vaccine sceptic. One cannot be just for Brexit; one must be for Brexit and against the UK Statistics Authority. Of course it is possible to resist such all-encompassing polarisation, and many people do. But the pull of tribal thinking on all of us is strong.

There are defences against the dead cat strategy. With skill, a fact-check may debunk a false claim without accidentally reinforcing it. But the strongest defence is an electorate that cares, that has more curiosity about the way the world really works than about cartoonish populists. If we let politicians drag facts into their swamp, we are letting them tug at democracy’s foundations.

Sunday, 14 August 2016

From Donald Trump to the Brexit campaign, outrageous untruths are almost a matter of course. How did we reach the point where ‘falsehood flies’?

Steven Poole in The Guardian

Champion of ‘free speech’: Donald Trump at a campaign rally last week. Photograph: Evan Vucci/AP

Not so long ago it was “soundbites” that were thought to be corrupting political debate by reducing complex ideas to slogans. The 1988 US presidential election was called the “soundbite election” by some commentators, the most famous example being George HW Bush’s promise: “Read my lips: No new taxes.” (Two years later Bush agreed to a bipartisan budget that did increase taxes.) It was a mysteriously brilliant piece of verbal engineering. Why would you have to read Bush’s lips when you could hear what he was saying on the TV? But the surprising image and arresting rhythm made it stick.

Soundbites and slogans (“Take Back Control”) still work. Trump, too, has a conventional campaign slogan: “Make America Great Again”. (Great how, exactly? By doing what? Don’t ask.) But he gets most publicity for his antic, apparently off-the-cuff remarks that rhetorically perform an absence of rhetoric. His real genius might be read as a satirical absolutism about the first amendment. If speech is genuinely free, there should be no consequences to speech whatsoever. And, to the mystification of the commenting class, this is what Trump repeatedly finds to be the case.

After the media furore surrounding Trump’s claim that Obama founded Isis, he tweeted: “THEY DON’T GET SARCASM?” Thus he rows back from any outrageous claim dreamed up by a brain that works like a cleverly programmed internet meme-generator. “I don’t know,” he says, all innocence, “that’s what some people are saying.” (No one was before he did.) Yet the idea Obama is the founder of Isis will stick in at least some voters’ minds come polling day, as will the imaginary Mexican wall (though they will probably have forgotten its “big beautiful door”) – just as the “£350m a week for the NHS” promise did for many Leave voters.

Trump is not a perversion of the tradition of political campaigning; he is the logical culmination of it. It doesn’t matter what you say, if it helps you get elected. Trump is not a liar, exactly, but a bullshitter. According to the canonical definition by the philosopher Harry Frankfurt, a liar still cares about the truth because he wants to conceal it from you. A bullshitter, on the other hand, simply doesn’t care what is true at all.

Trump is merely the most energetic current exploiter of a fact that modern politicians have long known: the media is broken, and you can mercilessly exploit its flaws to your own benefit. (That, after all, is what “spin doctors” are for.) If you repeat a lie often enough, then that claim becomes the story, and it’s what most people remember. And a structural confusion between “impartiality” and “balance” undermines the mission to inform of institutions such as the BBC. To be impartial would be to point out untruths wherever they come from. But to be “balanced” is to have a three-way between a presenter and two economists on opposite sides of some question. Never mind that one economist represents the views of 95% of the profession and the other is an ideologically blinkered outlier: the structure of the interview itself implies to the audience that the arguments are evenly divided.

In the age of social media, moreover, dubious political claims are packed into atomised fragments and attract thousands of enthusiastic retweets, while the people who help to redistribute them are unlikely ever to see a rebuttal that comes later or in someone else’s timeline. We’ve all moved on.

Social media is less a conversation than it is a virtually distributed riot of “happy firing” (a term for the celebratory shooting of assault rifles into the sky). That lies can go viral more quickly than the truth is another old observation. In 1710 Jonathan Swift wrote: “Falsehood flies, and the Truth comes limping after it.” But what is certain is that Twitter and Facebook now help it fly faster and further than ever before.

Nigel Farage proved the power of powerful slogans and images during the EU referendum campaign. Photograph: Philip Toscano/PA

Because attention is the currency of social media, public figures are incentivised to use outrage to vie for visibility, which further coarsens the public discourse – as when the American shock-journo Ann Coulter lately defended Trump by calling him a “victim of media rape” who is being blamed for “wearing a short skirt”. Any such outburst these days, along with the wave of overt post-Brexit racism in Britain, may be defended as a healthy refusal to kowtow to “political correctness”, a term that originally denoted the careful use of language so as not to needlessly upset people, and now just means common decency.

What, then, is to be done? The modern bullshitting demagogue succeeds because he says arresting and often amusing things that cut through the anomie of those who feel left behind by politics as usual. Exquisitely reasoned liberal conversation is exactly what turns those voters off. Lately it has been notable that Hillary Clinton, not previously considered the wittiest person in US politics, has used an impressive array of scripted zingers to put down her opponent. What the bullshitters do so well is define the rules of the game, so perhaps their opponents will have to play it at least to this extent, while trying to keep the moral high ground by still caring about what is true and what isn’t.

It’s not an edifying thought, but if the insurgent right is to have its Trumps and its Farages, maybe the centre and the left need their own versions too.

A Vote Leave battle bus, rebranded outside parliament in London by Greenpeace last month. Photograph: Jack Taylor/Getty Images

Donald Trump announced last week that Barack Obama was the “founder of Isis” and its “most valuable player”. Earlier he had hinted that gun activists might want to assassinate Hillary Clinton to prevent her appointing liberal justices to the Supreme Court. In Britain, meanwhile, calls for the moderation of violent political language after the death of Jo Cox have not resulted in much reduction of the gleeful talk of “stabbings” and “traitors”, and did not discourage Nigel Farage from exulting that the Brexit vote had been won “without a shot being fired”. In what some call an era of “post-truth politics”, public discourse seems more abusive and angry, and further from the ideal of reasoned conversation about social goods, than ever before. Is our political language broken?

Well, people have been complaining about the corruption of political language since political language existed. Confucius warned that a ruler should use the correct names for things, or social catastrophe would result. Orwell lamented that political language in his time was “designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind”. And the era of the “war on terror” gave rise to a whole new constellation of what I call Unspeak: carefully engineered phrases designed to smuggle in a biased point of view and shut down thought and argument – like “war on terror” itself.

Nor is flat-out lying in politics anything new. There is a marvellous 18th-century pamphlet usually attributed to John Arbuthnot, friend of Swift and Pope and founder of the Scriblerus club. It describes a yet-to-be-written book, The Art of Political Lying, in which the author will show “that the People have a Right to private Truth from their Neighbours ... but that they have no Right at all to Political Truth”.

The coinage “post-truth politics”, indeed, implies that there was once a golden age of politics in which its elevated practitioners spoke nothing but perfect truth. The sun never dawned on such a day. But perhaps what feels new to us now is the shamelessness of the lying, and the barefaced repeating of a lie repeatedly debunked. Arbuthnot cautioned that the same lie should not be “obstinately insisted upon”, but he did not live to see this strategy work so brilliantly during the EU referendum, with the Leave campaign’s claim that we sent £350m a week to the EU.

Shameless, too, was the haste with which this lie, having done its work, was disowned on the morning of the referendum result. It was a “mistake”, muttered Nigel Farage, before carefully lowering his snout back into the EU trough that continues to pay his MEP’s salary. This rather called to mind Paul Wolfowitz’s candid admission that the issue of Saddam’s alleged WMD was chosen as the justification for the Iraq war “for bureaucratic reasons”. The surprise, perhaps, is that you can show how the magic trick works, and people still believe it next time.

Donald Trump announced last week that Barack Obama was the “founder of Isis” and its “most valuable player”. Earlier he had hinted that gun activists might want to assassinate Hillary Clinton to prevent her appointing liberal justices to the Supreme Court. In Britain, meanwhile, calls for the moderation of violent political language after the death of Jo Cox have not resulted in much reduction of the gleeful talk of “stabbings” and “traitors”, and did not discourage Nigel Farage from exulting that the Brexit vote had been won “without a shot being fired”. In what some call an era of “post-truth politics”, public discourse seems more abusive and angry, and further from the ideal of reasoned conversation about social goods, than ever before. Is our political language broken?

Well, people have been complaining about the corruption of political language since political language existed. Confucius warned that a ruler should use the correct names for things, or social catastrophe would result. Orwell lamented that political language in his time was “designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind”. And the era of the “war on terror” gave rise to a whole new constellation of what I call Unspeak: carefully engineered phrases designed to smuggle in a biased point of view and shut down thought and argument – like “war on terror” itself.

Nor is flat-out lying in politics anything new. There is a marvellous 18th-century pamphlet usually attributed to John Arbuthnot, friend of Swift and Pope and founder of the Scriblerus club. It describes a yet-to-be-written book, The Art of Political Lying, in which the author will show “that the People have a Right to private Truth from their Neighbours ... but that they have no Right at all to Political Truth”.

The coinage “post-truth politics”, indeed, implies that there was once a golden age of politics in which its elevated practitioners spoke nothing but perfect truth. The sun never dawned on such a day. But perhaps what feels new to us now is the shamelessness of the lying, and the barefaced repeating of a lie repeatedly debunked. Arbuthnot cautioned that the same lie should not be “obstinately insisted upon”, but he did not live to see this strategy work so brilliantly during the EU referendum, with the Leave campaign’s claim that we sent £350m a week to the EU.

Shameless, too, was the haste with which this lie, having done its work, was disowned on the morning of the referendum result. It was a “mistake”, muttered Nigel Farage, before carefully lowering his snout back into the EU trough that continues to pay his MEP’s salary. This rather called to mind Paul Wolfowitz’s candid admission that the issue of Saddam’s alleged WMD was chosen as the justification for the Iraq war “for bureaucratic reasons”. The surprise, perhaps, is that you can show how the magic trick works, and people still believe it next time.

Champion of ‘free speech’: Donald Trump at a campaign rally last week. Photograph: Evan Vucci/AP

Not so long ago it was “soundbites” that were thought to be corrupting political debate by reducing complex ideas to slogans. The 1988 US presidential election was called the “soundbite election” by some commentators, the most famous example being George HW Bush’s promise: “Read my lips: No new taxes.” (Two years later Bush agreed to a bipartisan budget that did increase taxes.) It was a mysteriously brilliant piece of verbal engineering. Why would you have to read Bush’s lips when you could hear what he was saying on the TV? But the surprising image and arresting rhythm made it stick.

Soundbites and slogans (“Take Back Control”) still work. Trump, too, has a conventional campaign slogan: “Make America Great Again”. (Great how, exactly? By doing what? Don’t ask.) But he gets most publicity for his antic, apparently off-the-cuff remarks that rhetorically perform an absence of rhetoric. His real genius might be read as a satirical absolutism about the first amendment. If speech is genuinely free, there should be no consequences to speech whatsoever. And, to the mystification of the commenting class, this is what Trump repeatedly finds to be the case.

After the media furore surrounding Trump’s claim that Obama founded Isis, he tweeted: “THEY DON’T GET SARCASM?” Thus he rows back from any outrageous claim dreamed up by a brain that works like a cleverly programmed internet meme-generator. “I don’t know,” he says, all innocence, “that’s what some people are saying.” (No one was before he did.) Yet the idea Obama is the founder of Isis will stick in at least some voters’ minds come polling day, as will the imaginary Mexican wall (though they will probably have forgotten its “big beautiful door”) – just as the “£350m a week for the NHS” promise did for many Leave voters.

Trump is not a perversion of the tradition of political campaigning; he is the logical culmination of it. It doesn’t matter what you say, if it helps you get elected. Trump is not a liar, exactly, but a bullshitter. According to the canonical definition by the philosopher Harry Frankfurt, a liar still cares about the truth because he wants to conceal it from you. A bullshitter, on the other hand, simply doesn’t care what is true at all.

Trump is merely the most energetic current exploiter of a fact that modern politicians have long known: the media is broken, and you can mercilessly exploit its flaws to your own benefit. (That, after all, is what “spin doctors” are for.) If you repeat a lie often enough, then that claim becomes the story, and it’s what most people remember. And a structural confusion between “impartiality” and “balance” undermines the mission to inform of institutions such as the BBC. To be impartial would be to point out untruths wherever they come from. But to be “balanced” is to have a three-way between a presenter and two economists on opposite sides of some question. Never mind that one economist represents the views of 95% of the profession and the other is an ideologically blinkered outlier: the structure of the interview itself implies to the audience that the arguments are evenly divided.

In the age of social media, moreover, dubious political claims are packed into atomised fragments and attract thousands of enthusiastic retweets, while the people who help to redistribute them are unlikely ever to see a rebuttal that comes later or in someone else’s timeline. We’ve all moved on.

Social media is less a conversation than it is a virtually distributed riot of “happy firing” (a term for the celebratory shooting of assault rifles into the sky). That lies can go viral more quickly than the truth is another old observation. In 1710 Jonathan Swift wrote: “Falsehood flies, and the Truth comes limping after it.” But what is certain is that Twitter and Facebook now help it fly faster and further than ever before.

Nigel Farage proved the power of powerful slogans and images during the EU referendum campaign. Photograph: Philip Toscano/PA

Because attention is the currency of social media, public figures are incentivised to use outrage to vie for visibility, which further coarsens the public discourse – as when the American shock-journo Ann Coulter lately defended Trump by calling him a “victim of media rape” who is being blamed for “wearing a short skirt”. Any such outburst these days, along with the wave of overt post-Brexit racism in Britain, may be defended as a healthy refusal to kowtow to “political correctness”, a term that originally denoted the careful use of language so as not to needlessly upset people, and now just means common decency.

What, then, is to be done? The modern bullshitting demagogue succeeds because he says arresting and often amusing things that cut through the anomie of those who feel left behind by politics as usual. Exquisitely reasoned liberal conversation is exactly what turns those voters off. Lately it has been notable that Hillary Clinton, not previously considered the wittiest person in US politics, has used an impressive array of scripted zingers to put down her opponent. What the bullshitters do so well is define the rules of the game, so perhaps their opponents will have to play it at least to this extent, while trying to keep the moral high ground by still caring about what is true and what isn’t.

It’s not an edifying thought, but if the insurgent right is to have its Trumps and its Farages, maybe the centre and the left need their own versions too.

Wednesday, 21 August 2013

So the innocent have nothing to fear?

After David Miranda we now know where this leads

The destructive power of state snooping is on display for all to see. The press must not yield to this intimidation

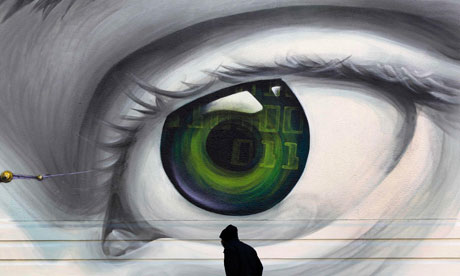

'But it remains worrying that many otherwise liberal-minded Britons seem reluctant to take seriously the abuses revealed in the nature and growth of state surveillance.' Photograph: Yannis Behrakis/Reuters

You've had your fun: now we want the stuff back. With these words the British government embarked on the most bizarre act of state censorship of the internet age. In a Guardian basement, officials from GCHQ gazed with satisfaction on a pile of mangled hard drives like so many book burners sent by the Spanish Inquisition. They were unmoved by the fact that copies of the drives were lodged round the globe. They wanted their symbolic auto-da-fe. Had the Guardian refused this ritual they said they would have obtained a search and destroy order from a compliant British court.

Two great forces are now in fierce but unresolved contention. The material revealed by Edward Snowden through the Guardian and the Washington Post is of a wholly different order from WikiLeaks and other recent whistle-blowing incidents. It indicates not just that the modern state is gathering, storing and processing for its own ends electronic communication from around the world; far more serious, it reveals that this power has so corrupted those wielding it as to put them beyond effective democratic control. It was not the scope of NSA surveillance that led to Snowden's defection. It was hearing his boss lie to Congress about it for hours on end.

Last week in Washington, Congressional investigators discovered that the America's foreign intelligence surveillance court, a body set up specifically to oversee the NSA, had itself been defied by the agency "thousands of times". It was victim to "a culture of misinformation" as orders to destroy intercepts, emails and files were simply disregarded; an intelligence community that seems neither intelligent nor a community commanding a global empire that could suborn the world's largest corporations, draw up targets for drone assassination, blackmail US Muslims into becoming spies and haul passengers off planes.

Yet like all empires, this one has bred its own antibodies. The American (or Anglo-American?) surveillance industry has grown so big by exploiting laws to combat terrorism that it is as impossible to manage internally as it is to control externally. It cannot sustain its own security. Some two million people were reported to have had access to the WikiLeaks material disseminated by Bradley Manning from his Baghdad cell. Snowden himself was a mere employee of a subcontractor to the NSA, yet had full access to its data. The thousands, millions, billions of messages now being devoured daily by US data storage centres may be beyond the dreams of Space Odyssey's HAL 9000. But even HAL proved vulnerable to human morality. Manning and Snowden cannot have been the only US officials to have pondered blowing a whistle on data abuse. There must be hundreds more waiting in the wings – and always will be.

There is clearly a case for prior censorship of some matters of national security. A state secret once revealed cannot be later rectified by a mere denial. Yet the parliamentary and legal institutions for deciding these secrets are plainly no longer fit for purpose. They are treated by the services they supposedly supervise with falsehoods and contempt. In America, the constitution protects the press from pre-publication censorship, leaving those who reveal state secrets to the mercy of the courts and the judgment of public debate – hence the Putinesque treatment of Manning and Snowden. But at least Congress has put the US director of national intelligence, James Clapper, under severe pressure. Even President Barack Obama has welcomed the debate and accepted that the Patriot Act may need revision.

In Britain, there has been no such response. GCHQ could boast to its American counterpart of its "light oversight regime compared to the US". Parliamentary and legal control is a charade, a patsy of the secrecy lobby. The press, normally robust in its treatment of politicians, seems cowed by a regime of informal notification of "defence sensitivity". This D-Notice system used to be confined to cases where the police felt lives to be at risk in current operations. In the case of Snowden the D-Notice has been used to warn editors off publishing material potentially embarrassing to politicians and the security services under the spurious claim that it "might give comfort to terrorists".

Most of the British press (though not the BBC, to its credit) has clearly felt inhibited. As with the "deterrent" smashing of Guardian hard drives and the harassing of David Miranda at Heathrow, a regime of prior restraint has been instigated in Britain whose apparent purpose seems to be simply to show off the security services as macho to their American friends.

Those who question the primacy of the "mainstream" media in the digital age should note that it has been two traditional newspapers, in London and Washington, that have researched, co-ordinated and edited the Snowden revelations. They have even held back material that the NSA and GCHQ had proved unable to protect. No blog, Twitter or Facebook campaign has the resources or the clout to confront the power of the state.

There is no conceivable way copies of the Snowden revelations seized this week at Heathrow could aid terrorism or "threaten the security of the British state" – as charged today by Mark Pritchard, an MP on the parliamentary committee on national security strategy. When the supposed monitors of the secret services merely parrot their jargon against press freedom, we should know this regime is not up to its job.

The war between state power and those holding it to account needs constant refreshment. As Snowden shows, the whistleblowers and hacktivists can win the occasional skirmish. But it remains worrying that many otherwise liberal-minded Britons seem reluctant to take seriously the abuses revealed in the nature and growth of state surveillance. The arrogance of this abuse is now widespread. The same police force that harassed Miranda for nine hours at Heathrow is the one recently revealed as using surveillance to blackmail Lawrence family supporters and draw up lists of trouble-makers to hand over to private contractors. We can see where this leads.

I hesitate to draw parallels with history, but I wonder how those now running the surveillance state – and their appeasers – would have behaved under the totalitarian regimes of the 20th century. We hear today so many phrases we have heard before. The innocent have nothing to fear. Our critics merely comfort the enemy. You cannot be too safe. Loyalty is all. As one official said in wielding his legal stick over the Guardian: "You have had your debate. There's no need to write any more."

Yes, there bloody well is.

Tuesday, 25 June 2013

How can we invest our trust in a government that spies on us?

We should not fear some Orwellian future state where we're subjected to total electronic scrutiny – it's our present reality

Bob Lambert, an undercover policeman who is alleged to have lied in court and has been accused by an MP of firebombing, was awarded an MBE in 2008 and now teaches at St Andrews University. Photograph: guardian.co.uk

'If you are a law-abiding citizen of this country, going about your business and your personal life, you have nothing to fear." That's how William Hague, the foreign secretary, responded to the revelations of mass surveillance in the US and the UK. Try telling that to Stephen Lawrence's family.

Four police officers were deployed to spy on the family and friends of the black teenager murdered by white racists. The Lawrences and the people who supported their fight for justice were law-abiding citizens going about their business. Yet undercover police were used, one of the spies now tells us, to hunt for "disinformation" and "dirt". Their purpose? "We were trying to stop the campaign in its tracks."

The two unfolding spy stories resonate powerfully with each other. One, gathered by Paul Lewis and Rob Evans, shows how police surveillance has been comprehensively perverted. Instead of defending citizens and the public realm, it has been used to protect the police from democratic scrutiny and stifle attempts to engage in politics.

The other, arising from the documents exposed by Edward Snowden, shows that the US and the UK have been involved in the mass interception of our phone calls and use of the internet. William Hague insists that we should "have confidence in the work of our intelligence agencies, and in their adherence to the law and democratic values". Why?

Here are a few of the things we have learned about undercover policing in Britain. A unit led by a policeman called Bob Lambert deployed officers to spy on peaceful activists. They adopted the identities of dead children and then infiltrated protest groups. Nine of the 11 known spies formed long-term relationships with women in the groups, in some cases (including Lambert's) fathering children with them. Then they made excuses and vanished.

They left a trail of ruined lives, fatherless children and women whose confidence and trust have been wrecked beyond repair. They have also walked away from other kinds of mayhem. On Friday we discovered that Lambert co-wrote the leaflet for which two penniless activists spent three years in the high court defending a libel action brought by McDonald's. The police never saw fit to inform the court that one of their own had been one of the authors.

Bob Lambert has been accused of using a false identity during a criminal trial. And, using parliamentary privilege, the MP Caroline Lucas alleged that he planted an incendiary device in a branch of Debenhams while acting as an agent provocateur. The device exploded, causing £300,000 of damage. Lambert denies the allegation.

Police and prosecutors also failed to disclose, during two trials of climate-change activists, that an undercover cop called Mark Kennedy had secretly taped their meetings, and that his recordings exonerated the protesters. Twenty people were falsely convicted. Those convictions were later overturned.

If the state is prepared to abuse its powers and instruments so widely and gravely in cases such as this, where there is a high risk of detection, and if it is prepared to intrude so far into people's lives that its officers live with activists and father their children, what is it not prepared to do while spying undetectably on our private correspondence?

Already we know that electronic surveillance has been used in this country for purposes other than the perennial justifications of catching terrorists, foiling foreign spies and preventing military attacks. It was deployed, for example, to spy on countries attending the G20 meeting the UK hosted in 2009. If the government does this to other states, which might have the capacity to detect its spying and which certainly have the means to object to it, what is it doing to defenceless citizens?

It looks as if William Hague may have misled parliament a fortnight ago. He claimed that "to intercept the content of any individual's communications in the UK requires a warrant signed personally by me, the home secretary, or by another secretary of state".

We now discover that these ministers can also issue general certificates, renewed every six months, which permit mass interception of the kind that GCHQ has been conducting. Among the certificates issued to GCHQ is a "global" one authorising all its operations, including the trawling of up to 600m phone calls and 39m gigabytes of electronic information a day. A million ministers, signing all day, couldn't keep up with that.

The best test of the good faith of an institution is the way it deals with past abuses. Despite two years of revelations about abusive police spying, the British government has yet to launch a full public inquiry. Bob Lambert, who ran the team, fathered a child by an innocent activist he deceived, co-wrote the McDonald's leaflet, is alleged to have lied in court and has been accused by an MP of firebombing, was awarded an MBE in 2008. He now teaches at St Andrews University, where he claims to have a background in "counter-terrorism".

The home office minister Nick Herbert has stated in parliament that it's acceptable for police officers to have sex with activists, for the sake of their "plausibility". Does this sound to you like a state in which we should invest our trust?

Talking to Sunday's Observer, a senior intelligence source expressed his or her concerns about mass surveillance. "If there was the wrong political change, it could be very dangerous. All you need is to have the wrong government in place." But it seems to me that any government prepared to subject its citizens to mass surveillance is by definition the wrong one. No one can be trusted with powers as wide and inscrutable as these.

In various forms – Conservative, New Labour, the coalition – we have had the wrong government for 30 years. Across that period its undemocratic powers have been consolidated. It has begun to form an elective dictatorship, in which the three major parties are united in their desire to create a security state; to wage unprovoked wars; to defend corporate power against democracy; to act as a doormat for the United States; to fight political dissent all the way to the bedroom and the birthing pool. There's no need to wait for the "wrong" state to arise to conclude that mass surveillance endangers liberty, pluralism and democracy. We're there already

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)