'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label police. Show all posts

Showing posts with label police. Show all posts

Sunday, 16 June 2024

Monday, 13 November 2023

Thursday, 8 September 2022

Sunday, 10 July 2022

Monday, 13 September 2021

Monday, 12 July 2021

Thursday, 18 March 2021

Sunday, 28 February 2021

Thursday, 28 January 2021

Sunday, 3 January 2021

Sunday, 13 September 2020

Sunday, 7 June 2020

Britain is not America. But we too are disfigured by deep and pervasive racism

Yes, it would be foolish to see only parallels in the US and UK experience. But to downplay our own problems would be shameful writes David Olusoga in The Guardian

FacebookTwitterPinterest The British actor John Boyega speaks to the crowd during a Black Lives Matter protest in Hyde Park on 3 June 2020 in London, England. Photograph: Justin Setterfield/Getty Images

Yet in the immediate aftermath of Floyd’s death there was little reason to imagine anything would be any different this time around. For African Americans, one of the most appalling aspects of Floyd’s murder was that they had seen it all before. The same story with the same outcome, all that changed was the name of the victim – Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Sandra Bland, Tamir Rice, Philando Castile, Walter Scott.

For many black Britons, Floyd’s death stirred memories of another list of names, those of the members of their community killed or rendered disabled in similar circumstances at the hands of the British police or immigration officers. On Tuesday, the Black Cultural Archives in Brixton, south London – the closest thing we have in this country to a museum to the black British experience – tweeted the names and the photographs of some of them – Mark Duggan, Sheku Bayoh, Sean Rigg, Sarah Reed, Cherry Groce, Leon Briggs, Christopher Alder, Brian Douglas.

Yet almost instantly a predictable chorus of voices, emanating from predictable corners of British public life, rose up to dismiss the whole thing as an irrelevance. Using a familiar playbook, they accused those black Britons who see reflections of their own situation in the experiences of African Americans of making false comparisons.

The US situation is unique in both its depth and ferocity, they say, so that no parallels can be drawn with the situation in Britain. The smoke-and-mirrors aspect of this argument is that it attempts to focus attention solely on police violence, rather than the racism that inspired it. Those who make it usually point to the ubiquity of firearms in US law enforcement, as proof that the US reality is beyond meaningful comparison. But firearms had nothing to do with the killing of George Floyd. Neither were they a factor in the death of Freddie Gray or the sidewalk killing of Eric Garner, who, like Floyd, pleaded for his life, saying 11 times to the officers who pinned him down: “I can’t breathe”, the same words Floyd used in his final moments. Nor were guns involved in many of the cases when black people have died in custody or during arrest in Britain.

Excusing or downplaying British racism with comparisons to the US is a bad habit with a long history

When black Britons draw parallels between their experiences and those of African Americans, they are not suggesting that those experiences are identical. Few people would deny that in many respects life is better for non-white people in the UK than in the US. The problem is that it is not as “better” as some like to believe. Black men are stopped and searched at nine times the rate of white men. Black people make up 3% of the population of England and Wales but account for 12% of the prison population and not since 1971 have British police officers been prosecuted for the killing of a black man, and even then they were charged with the lesser crime of manslaughter and that charge was later dropped.

To say that the racism that infects parts of our police force and criminal justice system is less virulent than that which poisons the lives of 40 million African Americans is not much of a boast. Is that really the extent of our ambition – to be a somewhat less racist nation than one led by a man who describes white nationalists and members of the Ku Klux Klan as “very fine people”? Surely we who dwell in what the actor Laurence Fox recently assured us is “the most tolerant, lovely country in Europe” have higher hopes?

Excusing or downplaying British racism with comparisons to the US is a bad habit with a long history. It began in 1807, with the abolition of the slave trade and picked up steam three decades later with the end of British slavery, twin events that marked the beginning of 200 years of moral posturing and historical amnesia. The Victorian readers who rightly wept over Uncle Tom’s Cabin, for example, conveniently forgot which nation had carried his ancestors into slavery and didn’t dwell on the fact that most of the cotton produced by American slaves like him was shipped to Liverpool.

For two centuries, we have deployed American racism as a distraction. It’s as if we find it easier to recognise American forms of racism than we do our own home-grown varieties. Convenient, as pointing fingers is always more comforting than looking in the mirror.

Demonstrator at a Black Lives Matter protest on 6 June 2020 in Cardiff. Photograph: Matthew Horwood/Getty Images

One of the more pertinent statements made during this past extraordinary week appeared in one of the last places I would have thought to look – in the pages of Vogue, not a publication I instinctively turn to at a moment of profound political tension.

“Racism is a global issue. Racism is a British issue. It is not one that is merely confined to the United States – it is everywhere, and it is systemic,” wrote Edward Enninful, the editor-in-chief of the magazine’s British edition. The ubiquity of racism has been brought to stark and sudden attention by the killing of George Floyd and by the unprecedented wave of protests, demonstrations and rioting that followed.

Filmed by many witnesses and now viewed millions of times, the killing of Floyd by a Minnesota policeman, a 21st-century lynching, is so sickening a crime that the revulsion it has induced has become a global phenomenon.

The demonstrators and activists who have taken to the streets have, however, been motivated by more than revulsion. They have also been stirred to action by acknowledging a fundamental truth – that the killing of Floyd has to be understood as a symptom of systemic racism. By building their campaign around that reality they have promoted radical and challenging conversations – in countries on both sides of the Atlantic – about the nature of racism and the actions that people of all races can take in eliminating it. These are conversations that we have needed for a very long time.

Led by young people, many of them inspired by Black Lives Matter, and involving people of all ethnicities, the protests have morphed into a worldwide anti-racist movement. No longer is this moment solely about police violence nor is it limited to America. Both online and on the streets it is calling out racism, wherever it exists and in whatever forms it is found. In both the US and in Europe, people are asking, tentatively, if this might be a defining moment of change.

One of the more pertinent statements made during this past extraordinary week appeared in one of the last places I would have thought to look – in the pages of Vogue, not a publication I instinctively turn to at a moment of profound political tension.

“Racism is a global issue. Racism is a British issue. It is not one that is merely confined to the United States – it is everywhere, and it is systemic,” wrote Edward Enninful, the editor-in-chief of the magazine’s British edition. The ubiquity of racism has been brought to stark and sudden attention by the killing of George Floyd and by the unprecedented wave of protests, demonstrations and rioting that followed.

Filmed by many witnesses and now viewed millions of times, the killing of Floyd by a Minnesota policeman, a 21st-century lynching, is so sickening a crime that the revulsion it has induced has become a global phenomenon.

The demonstrators and activists who have taken to the streets have, however, been motivated by more than revulsion. They have also been stirred to action by acknowledging a fundamental truth – that the killing of Floyd has to be understood as a symptom of systemic racism. By building their campaign around that reality they have promoted radical and challenging conversations – in countries on both sides of the Atlantic – about the nature of racism and the actions that people of all races can take in eliminating it. These are conversations that we have needed for a very long time.

Led by young people, many of them inspired by Black Lives Matter, and involving people of all ethnicities, the protests have morphed into a worldwide anti-racist movement. No longer is this moment solely about police violence nor is it limited to America. Both online and on the streets it is calling out racism, wherever it exists and in whatever forms it is found. In both the US and in Europe, people are asking, tentatively, if this might be a defining moment of change.

FacebookTwitterPinterest The British actor John Boyega speaks to the crowd during a Black Lives Matter protest in Hyde Park on 3 June 2020 in London, England. Photograph: Justin Setterfield/Getty Images

Yet in the immediate aftermath of Floyd’s death there was little reason to imagine anything would be any different this time around. For African Americans, one of the most appalling aspects of Floyd’s murder was that they had seen it all before. The same story with the same outcome, all that changed was the name of the victim – Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Sandra Bland, Tamir Rice, Philando Castile, Walter Scott.

For many black Britons, Floyd’s death stirred memories of another list of names, those of the members of their community killed or rendered disabled in similar circumstances at the hands of the British police or immigration officers. On Tuesday, the Black Cultural Archives in Brixton, south London – the closest thing we have in this country to a museum to the black British experience – tweeted the names and the photographs of some of them – Mark Duggan, Sheku Bayoh, Sean Rigg, Sarah Reed, Cherry Groce, Leon Briggs, Christopher Alder, Brian Douglas.

Yet almost instantly a predictable chorus of voices, emanating from predictable corners of British public life, rose up to dismiss the whole thing as an irrelevance. Using a familiar playbook, they accused those black Britons who see reflections of their own situation in the experiences of African Americans of making false comparisons.

The US situation is unique in both its depth and ferocity, they say, so that no parallels can be drawn with the situation in Britain. The smoke-and-mirrors aspect of this argument is that it attempts to focus attention solely on police violence, rather than the racism that inspired it. Those who make it usually point to the ubiquity of firearms in US law enforcement, as proof that the US reality is beyond meaningful comparison. But firearms had nothing to do with the killing of George Floyd. Neither were they a factor in the death of Freddie Gray or the sidewalk killing of Eric Garner, who, like Floyd, pleaded for his life, saying 11 times to the officers who pinned him down: “I can’t breathe”, the same words Floyd used in his final moments. Nor were guns involved in many of the cases when black people have died in custody or during arrest in Britain.

Excusing or downplaying British racism with comparisons to the US is a bad habit with a long history

When black Britons draw parallels between their experiences and those of African Americans, they are not suggesting that those experiences are identical. Few people would deny that in many respects life is better for non-white people in the UK than in the US. The problem is that it is not as “better” as some like to believe. Black men are stopped and searched at nine times the rate of white men. Black people make up 3% of the population of England and Wales but account for 12% of the prison population and not since 1971 have British police officers been prosecuted for the killing of a black man, and even then they were charged with the lesser crime of manslaughter and that charge was later dropped.

To say that the racism that infects parts of our police force and criminal justice system is less virulent than that which poisons the lives of 40 million African Americans is not much of a boast. Is that really the extent of our ambition – to be a somewhat less racist nation than one led by a man who describes white nationalists and members of the Ku Klux Klan as “very fine people”? Surely we who dwell in what the actor Laurence Fox recently assured us is “the most tolerant, lovely country in Europe” have higher hopes?

Excusing or downplaying British racism with comparisons to the US is a bad habit with a long history. It began in 1807, with the abolition of the slave trade and picked up steam three decades later with the end of British slavery, twin events that marked the beginning of 200 years of moral posturing and historical amnesia. The Victorian readers who rightly wept over Uncle Tom’s Cabin, for example, conveniently forgot which nation had carried his ancestors into slavery and didn’t dwell on the fact that most of the cotton produced by American slaves like him was shipped to Liverpool.

For two centuries, we have deployed American racism as a distraction. It’s as if we find it easier to recognise American forms of racism than we do our own home-grown varieties. Convenient, as pointing fingers is always more comforting than looking in the mirror.

Tuesday, 2 June 2020

The Power of Crowds

Even before the pandemic, mass gatherings were under threat from draconian laws and corporate seizure of public space. Yet history shows that the crowd always finds a way to return. By Dan Hancox in The Guardian

As lockdown loomed in March, I became obsessed with a football anthem for a team 400 miles away. I had read a news story about Edinburgh residents singing a Proclaimers song called Sunshine on Leith from their balconies. I didn’t know the song, and when I looked it up, I found a glorious video of 26,000 Hibernian fans singing it in a sun-drenched Hampden Park, after a long-hoped-for Scottish Cup win in 2016. Both teams had left the pitch, and the Rangers’ half of the stadium was empty. It looked like a concert in which the fans were simultaneously the performer and the audience.

I was entranced. I watched it again, and again. The sight and sound of this collective joy was transcendent: tens of thousands of green-and-white scarves held aloft, everyone belting out the song at the tops of their lungs. When the crowd hits the chorus, the volume levels on the shaky smartphone video blow their limit, exploding into a delirious roar of noise. I thought of something that one of the leaders of the nationwide “Tuneless Choirs” – specifically for people who can’t sing – once said: “If you get enough people singing together, with enough volume, it always sounds good.” Our individual failings are submerged; we become greater than the sum of our meagre parts. Anthems sung alone sound thin and absurd – think of the spectacle of a pop star bellowing the Star-Spangled Banner at the Super Bowl. Anthems need the warmth of harmony, or even the chafing of dissonance. They need the full sound of bodies brushing up against each other in pride, joy or righteousness.

Sunshine on Leith is ostensibly a love song, but in this instance, it wasn’t being sung to a lover, or to the victorious Hibs players, or to the football club, or to Leith – the 26,000 singers seemed to be addressing each other. In their many and varied voices, they had transformed it into a love song to the crowd: “While I’m worth my room on this Earth, I will be with you / While the chief puts sunshine on Leith, I’ll thank him for his work, and your birth and my birth.” In the YouTube comments, fans of other clubs, from Millwall to Lyon – and even Hibs’ arch-rivals Hearts – congratulate the Hibbies; not on the cup victory, not on the performance of the team, but that of the crowd. “Even the riot police horses shedding tears there,” observes one.

As the lockdown commenced, I found myself cueing up other songs that reminded me of crowds. In the way a single snatch of melody can instantly remind you of an ex, or an old friend, I wanted songs that reminded me of what it’s like to be with thousands of strangers. I listened to Drake’s Nice for What and Koffee’s Toast, which took me back to swaying tipsily in the crush of Notting Hill carnival, of being giddily overwhelmed, as the juddering sub-bass moved in waves through a million ribcages.

Perhaps this is too pessimistic. The 21st-century domestication of the crowd does not in itself snuff out its power. The experience of being part of a crowd can still change us in all manner of unexpected ways. If one thing should be retained from academics’ debunking of the myth of the crowd as a single beast with one brain and a thousand limbs, it is precisely that the diversity of the individuals within the crowd is what makes it so vital.

Far from behaving as one, everyone has different cooperation thresholds for participation, and there are some who by their nature will always be the first in the pool. For better or worse, crowds empower more shy or conservative people to do what they might not have done otherwise: to pronounce their political beliefs or proclaim their sexual orientation in public, to sing about their heartfelt feelings for Sergio Agüero, to occupy a bank, to throw a brick, to fight with strangers, to dance to Abba in the concourse of a major intercity railway station.

Being a crowd member is not a muscle that will atrophy through lack of use – our knack for it, and need for it, has a much longer history than the months we will be required to keep our physical distance. The desire to be part of the crowd is a part of who we are, and it will not be dispersed so easily.

As lockdown loomed in March, I became obsessed with a football anthem for a team 400 miles away. I had read a news story about Edinburgh residents singing a Proclaimers song called Sunshine on Leith from their balconies. I didn’t know the song, and when I looked it up, I found a glorious video of 26,000 Hibernian fans singing it in a sun-drenched Hampden Park, after a long-hoped-for Scottish Cup win in 2016. Both teams had left the pitch, and the Rangers’ half of the stadium was empty. It looked like a concert in which the fans were simultaneously the performer and the audience.

I was entranced. I watched it again, and again. The sight and sound of this collective joy was transcendent: tens of thousands of green-and-white scarves held aloft, everyone belting out the song at the tops of their lungs. When the crowd hits the chorus, the volume levels on the shaky smartphone video blow their limit, exploding into a delirious roar of noise. I thought of something that one of the leaders of the nationwide “Tuneless Choirs” – specifically for people who can’t sing – once said: “If you get enough people singing together, with enough volume, it always sounds good.” Our individual failings are submerged; we become greater than the sum of our meagre parts. Anthems sung alone sound thin and absurd – think of the spectacle of a pop star bellowing the Star-Spangled Banner at the Super Bowl. Anthems need the warmth of harmony, or even the chafing of dissonance. They need the full sound of bodies brushing up against each other in pride, joy or righteousness.

Sunshine on Leith is ostensibly a love song, but in this instance, it wasn’t being sung to a lover, or to the victorious Hibs players, or to the football club, or to Leith – the 26,000 singers seemed to be addressing each other. In their many and varied voices, they had transformed it into a love song to the crowd: “While I’m worth my room on this Earth, I will be with you / While the chief puts sunshine on Leith, I’ll thank him for his work, and your birth and my birth.” In the YouTube comments, fans of other clubs, from Millwall to Lyon – and even Hibs’ arch-rivals Hearts – congratulate the Hibbies; not on the cup victory, not on the performance of the team, but that of the crowd. “Even the riot police horses shedding tears there,” observes one.

As the lockdown commenced, I found myself cueing up other songs that reminded me of crowds. In the way a single snatch of melody can instantly remind you of an ex, or an old friend, I wanted songs that reminded me of what it’s like to be with thousands of strangers. I listened to Drake’s Nice for What and Koffee’s Toast, which took me back to swaying tipsily in the crush of Notting Hill carnival, of being giddily overwhelmed, as the juddering sub-bass moved in waves through a million ribcages.

Notting Hill carnival in 2012. Photograph: Miles Davies/Alamy Stock Photo

I missed the disinhibition of dancing in a dark, low-ceilinged club. I missed screaming into the cold winter air of the AFC Wimbledon terraces about an outrageous refereeing decision. I missed the joy of chanting and feeling my own thin voice being made whole by others joining it in unison. I missed the tingling mixture of anxiety and vertigo of the moment you first step out into a festival or football or carnival or protest crowd, a feeling of over-stimulation, the ripples of noise and colour jostling for your attention, the anticipation of being subsumed in the crowd and yet powered up by it – of losing a part of yourself, and your independence, and being glad to. I missed the strange alchemy of congregation, when your brain pulses with the validation of being with so many people who have chosen the same path. How could I be wrong? Look, all these people are here, too.

While many of us were missing crowds, the realities of Covid-19 meant they had taken on a completely new meaning. Gathering with others was suddenly, paradoxically antisocial: it suggested you were careless about viral transmission of a deadly disease, more interested in your own short-term social needs than the lives of strangers. The very sight of a crowd suddenly seemed alarming. We shook our heads at rumours of parties, and shared pictures of Cheltenham festival or the Stereophonics’ Cardiff gigs as if they were clips from horror films. Festivals, congregations, assemblies, raves, processions, choirs, rallies, demonstrations, audiences in stadiums, halls, clubs, theatres and cinemas – gatherings of any kind became fatal. As lockdown begins to ease, people are again gathering to socialise in parks and on beaches, and to rail against injustice in Black Lives Matter and Extinction Rebellion protests, but crowds as we used to know them won’t be coming back for many months to come.

While the pandemic has made exceptional demands of us, even before the Covid-19 lockdown, crowds have been under threat. We were becoming ever more atomised, and pushed further into our homes, and crowds were becoming more domesticated, enclosed, surveilled and expensive to be a part of. Our opportunities to gather freely, in both senses of the word, have greatly diminished since the 90s. And yet, throughout human history, there has always been something pleasingly resilient about the crowd: however many new ways are found to disperse it, it will always find a way to reconvene.

Crowds have always had a bad rap: there is no gentle mob, no friendly pack. The same disinhibition that allows for moments of great joy can also enable grotesque crimes. The people who gathered to watch lynchings in the US, or recent attacks on Muslims by groups of Hindu nationalists in India, were not just bystanders but participants. Their presence and acquiescence helped make the violence possible. And just as the people at the back of the crowd empower those at the front, the reverse can be true. The hooligan firm leader who throws the first cafe chair across a moonlit plaza on a balmy European away day makes it easier for more timid members of the crowd to cross their own “cooperation threshold” and join in.

Even celebratory or worshipful crowds can go wrong, and when they do, they generate an unmatched horror. Few things strike fear like the the idea of mass panic, few words as chilling as “caught up in a stampede” or “trampled to death”. The horror of the 96 dead at Hillsborough in 1989, or the 21 suffocated at the 2010 Berlin Love Parade, or the 2,400 killed in a crowd collapse at the 2015 Hajj, gnaws at something deep in our psyches. For some people, even a peaceful and orderly crowd can be scary, triggering intense anxiety or PTSD.

Informed by tragedies, uprisings and protests alike, for a long time crowds were seen as inherently dangerous and lobotomising. But during the past couple of decades, thanks to work by social psychologists, behavioural scientists and anthropologists, a new understanding of the complexity of crowd behaviour has become increasingly influential.

I missed the disinhibition of dancing in a dark, low-ceilinged club. I missed screaming into the cold winter air of the AFC Wimbledon terraces about an outrageous refereeing decision. I missed the joy of chanting and feeling my own thin voice being made whole by others joining it in unison. I missed the tingling mixture of anxiety and vertigo of the moment you first step out into a festival or football or carnival or protest crowd, a feeling of over-stimulation, the ripples of noise and colour jostling for your attention, the anticipation of being subsumed in the crowd and yet powered up by it – of losing a part of yourself, and your independence, and being glad to. I missed the strange alchemy of congregation, when your brain pulses with the validation of being with so many people who have chosen the same path. How could I be wrong? Look, all these people are here, too.

While many of us were missing crowds, the realities of Covid-19 meant they had taken on a completely new meaning. Gathering with others was suddenly, paradoxically antisocial: it suggested you were careless about viral transmission of a deadly disease, more interested in your own short-term social needs than the lives of strangers. The very sight of a crowd suddenly seemed alarming. We shook our heads at rumours of parties, and shared pictures of Cheltenham festival or the Stereophonics’ Cardiff gigs as if they were clips from horror films. Festivals, congregations, assemblies, raves, processions, choirs, rallies, demonstrations, audiences in stadiums, halls, clubs, theatres and cinemas – gatherings of any kind became fatal. As lockdown begins to ease, people are again gathering to socialise in parks and on beaches, and to rail against injustice in Black Lives Matter and Extinction Rebellion protests, but crowds as we used to know them won’t be coming back for many months to come.

While the pandemic has made exceptional demands of us, even before the Covid-19 lockdown, crowds have been under threat. We were becoming ever more atomised, and pushed further into our homes, and crowds were becoming more domesticated, enclosed, surveilled and expensive to be a part of. Our opportunities to gather freely, in both senses of the word, have greatly diminished since the 90s. And yet, throughout human history, there has always been something pleasingly resilient about the crowd: however many new ways are found to disperse it, it will always find a way to reconvene.

Crowds have always had a bad rap: there is no gentle mob, no friendly pack. The same disinhibition that allows for moments of great joy can also enable grotesque crimes. The people who gathered to watch lynchings in the US, or recent attacks on Muslims by groups of Hindu nationalists in India, were not just bystanders but participants. Their presence and acquiescence helped make the violence possible. And just as the people at the back of the crowd empower those at the front, the reverse can be true. The hooligan firm leader who throws the first cafe chair across a moonlit plaza on a balmy European away day makes it easier for more timid members of the crowd to cross their own “cooperation threshold” and join in.

Even celebratory or worshipful crowds can go wrong, and when they do, they generate an unmatched horror. Few things strike fear like the the idea of mass panic, few words as chilling as “caught up in a stampede” or “trampled to death”. The horror of the 96 dead at Hillsborough in 1989, or the 21 suffocated at the 2010 Berlin Love Parade, or the 2,400 killed in a crowd collapse at the 2015 Hajj, gnaws at something deep in our psyches. For some people, even a peaceful and orderly crowd can be scary, triggering intense anxiety or PTSD.

Informed by tragedies, uprisings and protests alike, for a long time crowds were seen as inherently dangerous and lobotomising. But during the past couple of decades, thanks to work by social psychologists, behavioural scientists and anthropologists, a new understanding of the complexity of crowd behaviour has become increasingly influential.

A depiction of the Peterloo Massacre in Manchester in 1819, when cavalry charged on a crowd at a political rally. Photograph: Alamy Stock Photo

For most of us, a crowd can be an alluring thing, because the desire to be among the throng seems to be innate. Gathering together for ritualistic celebrations – dancing, chanting, festivalling, costuming, singing, marching – goes back almost as far as we have any record of human behaviour. In 2003, 13,000-year-old cave paintings were discovered in Nottinghamshire that seemed to show “conga lines” of dancing women. According to the archeologist Paul Pettitt, the paintings matched others across Europe, indicating that they were part of a continent-wide Paleolithic culture of collective singing and dancing.

In Barbara Ehrenreich’s 2007 book Dancing in the Streets: A History of Collective Joy, she draws on the work of anthropologists including Robin Dunbar to argue that dancing and music-making was a social glue that helped stone-age families join together in groups larger than the family unit, to hunt and protect themselves from predators. For Ehrenreich, rituals of collective joy are as intrinsic to human development as speech. More recent experiments by Dunbar and his colleagues have suggested that the capacity of singing together to bond groups of strangers shows it “may have played a role in the evolutionary success of modern humans over their early relatives”.

The power of crowds has long fixated religious and secular leaders alike, who have sought to harness communal energy for their own glorification, or to tame mass gatherings when they start to take on a momentum of their own. Ehrenreich records the medieval Christian church’s long battle to eradicate unruly, ecstatic or immoderate dancing from the congregation. In later centuries, as the reformation and industrial revolution proceeded, festivals, feast days, sports, revels and ecstatic rituals of countless kinds were outlawed for their tendency to result in drunken, pagan or otherwise ungodly behaviour. Between the 17th and 20th centuries, there were “literally thousands of acts of legislation introduced which attempted to outlaw carnival and popular festivity from European life,” wrote Peter Stallybrass and Allon White in The Politics and Poetics of Transgression.

It wasn’t until the 19th century, as industrialising cities exploded in size, that the formal study of crowd psychology and herd behaviour emerged. Reflecting on the French Revolution a century earlier, thinkers such as Gustave Le Bon helped promote the idea that a crowd is always on the verge of becoming a mob. Stirred up by agitators, crowds could quickly turn to violence, sweeping up even good, upstanding citizens in their collective madness. “By the mere fact that he forms part of an organised crowd,” Le Bon wrote, “a man descends several rungs in the ladder of civilisation.”

While the discipline of crowd psychology has moved on considerably since the days of Le Bon, these early theories still retain their hold, says Clifford Stott, a professor of social psychology at Keele University. Much of the media coverage of the riots that broke out across England in 2011 echoed the explanations of the 19th-century pioneers of crowd psychology: they were a pathological intrusion into civilised society, a contagion, spread by agitators, of the normally stable and contented body politic. Focus fell, in particular, on ill-defined “criminal gangs” stirring things up, possibly coordinating things via BlackBerry Messenger. The foot soldiers – 30,000 people were thought to have participated – were depicted as feral thugs. Hordes. Animals. The frontpage headlines were clear: “Rule of the mob”, “Yob rule”, “Flaming morons”. Purportedly liberal voices clamoured for David Cameron to send in the army. Shoot looters on sight. Wheel in the water cannon.

For most of us, a crowd can be an alluring thing, because the desire to be among the throng seems to be innate. Gathering together for ritualistic celebrations – dancing, chanting, festivalling, costuming, singing, marching – goes back almost as far as we have any record of human behaviour. In 2003, 13,000-year-old cave paintings were discovered in Nottinghamshire that seemed to show “conga lines” of dancing women. According to the archeologist Paul Pettitt, the paintings matched others across Europe, indicating that they were part of a continent-wide Paleolithic culture of collective singing and dancing.

In Barbara Ehrenreich’s 2007 book Dancing in the Streets: A History of Collective Joy, she draws on the work of anthropologists including Robin Dunbar to argue that dancing and music-making was a social glue that helped stone-age families join together in groups larger than the family unit, to hunt and protect themselves from predators. For Ehrenreich, rituals of collective joy are as intrinsic to human development as speech. More recent experiments by Dunbar and his colleagues have suggested that the capacity of singing together to bond groups of strangers shows it “may have played a role in the evolutionary success of modern humans over their early relatives”.

The power of crowds has long fixated religious and secular leaders alike, who have sought to harness communal energy for their own glorification, or to tame mass gatherings when they start to take on a momentum of their own. Ehrenreich records the medieval Christian church’s long battle to eradicate unruly, ecstatic or immoderate dancing from the congregation. In later centuries, as the reformation and industrial revolution proceeded, festivals, feast days, sports, revels and ecstatic rituals of countless kinds were outlawed for their tendency to result in drunken, pagan or otherwise ungodly behaviour. Between the 17th and 20th centuries, there were “literally thousands of acts of legislation introduced which attempted to outlaw carnival and popular festivity from European life,” wrote Peter Stallybrass and Allon White in The Politics and Poetics of Transgression.

It wasn’t until the 19th century, as industrialising cities exploded in size, that the formal study of crowd psychology and herd behaviour emerged. Reflecting on the French Revolution a century earlier, thinkers such as Gustave Le Bon helped promote the idea that a crowd is always on the verge of becoming a mob. Stirred up by agitators, crowds could quickly turn to violence, sweeping up even good, upstanding citizens in their collective madness. “By the mere fact that he forms part of an organised crowd,” Le Bon wrote, “a man descends several rungs in the ladder of civilisation.”

While the discipline of crowd psychology has moved on considerably since the days of Le Bon, these early theories still retain their hold, says Clifford Stott, a professor of social psychology at Keele University. Much of the media coverage of the riots that broke out across England in 2011 echoed the explanations of the 19th-century pioneers of crowd psychology: they were a pathological intrusion into civilised society, a contagion, spread by agitators, of the normally stable and contented body politic. Focus fell, in particular, on ill-defined “criminal gangs” stirring things up, possibly coordinating things via BlackBerry Messenger. The foot soldiers – 30,000 people were thought to have participated – were depicted as feral thugs. Hordes. Animals. The frontpage headlines were clear: “Rule of the mob”, “Yob rule”, “Flaming morons”. Purportedly liberal voices clamoured for David Cameron to send in the army. Shoot looters on sight. Wheel in the water cannon.

Riots in Hackney, east London in August 2011. Photograph: Luke Macgregor/Reuters

“What we need to recognise is that from a scientific perspective, classical [crowd] theory has no validity,” says Stott. “It doesn’t explain or predict the behaviours it purports to explain and predict. And yet everywhere you look, the narrative is still there.” The reason, he argues, is straightforward: “It’s very, very convenient for dominant and powerful groups,” Stott says. “It pathologises, decontextualises and renders meaningless crowd violence, and therefore legitimises its repression.” As Stott notes, by shifting the blame to the madness of crowds, it also conveniently allows the powerful to avoid scrutinising their own responsibility for the violence. Last week, when the US attorney general blamed “outside agitators” for stirring up violence, and Donald Trump referred to “professionally managed” “thugs”, they were drawing on exactly the ideas that Le Bon sketched out in the 19th century.

In recent decades, detailed analytical research has produced ever-more sophisticated insights into crowd behaviour, many of which disprove these long-standing assumptions. “Crowds have an amazing ability to police themselves, self-regulate, and actually display a lot of pro-social behaviour, supporting others in their group,” says Anne Templeton, an academic at Edinburgh University who studies crowd psychology. She points to the 2017 Manchester Arena terrorist attack, in which CCTV footage showed members of the public performing first aid on the wounded before emergency services arrived, and Mancunians rushed to provide food, shelter, transport and emotional support for the victims. “People provide an amazing amount of help in emergencies to people they don’t know, especially when they’re part of an in-group.”

Strange things happen to our brains when we’re in a crowd we’ve chosen to be part of, says Templeton. We don’t just feel happier and more confident, we also have a lower threshold of disgust. This is why festivalgoers will happily share drinks (and by dint of their proximity, sweat) with strangers, or Hajj pilgrims will share the sometimes bloody razors used to shave their heads. In a crowd, we feel safer from harm.

If we now have a better grasp of the complexity of crowd dynamics, the core truth about them is relatively simple: they have the potential to magnify both the good and bad in us. The loss of self in a crowd can lead to unthinkable violence, just as it can ecstatic transcendence. What is striking is that, in recent decades, the latter has troubled the British establishment every bit as much as the former.

‘The open crowd is the true crowd,” wrote Elias Canetti in his 1960 book Crowds and Power – “the crowd abandoning itself freely to its natural urge for growth”, rather than those hemmed in by authorities, limited in shape and size. The Sermon on the Mount, he writes, was delivered to an open crowd. The obsequious flock, the brainwashed cult, the army marching in lock-step, is a world away from a fluid, democratic, sometimes anarchic congregation of the people. These open crowds have become harder to find, and harder to keep open.

Contemporary Britain’s idea of the crowd was formed by two explosions in unruly mass culture at the end of the last century. First, by 70s and 80s football fandom and its manifold sins, and the avoidable tragedy of Hillsborough – a tragedy created by the authorities’ views of the crowd as animalistic thugs, a fear and loathing that permeated the media, police, political class and football authorities. And second, by the acid house explosion and rave scene of the late 80s and early 90s, a subcultural surge of illegal or at least illicit “free parties” in fields and warehouses across the country. Both cultures flourished in spite of widespread media demonisation, both fought the law – and in both cases, the law won. Things have never been the same since for people who wish to assemble on their own terms.

The policing, containment and enclosure of “free” raves is particularly instructive, suggesting that the authorities fear a happy crowd as much as a pitchfork-carrying one. For the novelist Hari Kunzru, reflecting on his 90s youth a few years ago, approaching the site of a rave, feeling “the bass pulsing up ahead, the excitement was almost unbearable. A mass of dancers lifting up like a single body … [an] ecstatic fantasy of community, a zone where we were networked with each other, rather than with the office switchboard.”

“What we need to recognise is that from a scientific perspective, classical [crowd] theory has no validity,” says Stott. “It doesn’t explain or predict the behaviours it purports to explain and predict. And yet everywhere you look, the narrative is still there.” The reason, he argues, is straightforward: “It’s very, very convenient for dominant and powerful groups,” Stott says. “It pathologises, decontextualises and renders meaningless crowd violence, and therefore legitimises its repression.” As Stott notes, by shifting the blame to the madness of crowds, it also conveniently allows the powerful to avoid scrutinising their own responsibility for the violence. Last week, when the US attorney general blamed “outside agitators” for stirring up violence, and Donald Trump referred to “professionally managed” “thugs”, they were drawing on exactly the ideas that Le Bon sketched out in the 19th century.

In recent decades, detailed analytical research has produced ever-more sophisticated insights into crowd behaviour, many of which disprove these long-standing assumptions. “Crowds have an amazing ability to police themselves, self-regulate, and actually display a lot of pro-social behaviour, supporting others in their group,” says Anne Templeton, an academic at Edinburgh University who studies crowd psychology. She points to the 2017 Manchester Arena terrorist attack, in which CCTV footage showed members of the public performing first aid on the wounded before emergency services arrived, and Mancunians rushed to provide food, shelter, transport and emotional support for the victims. “People provide an amazing amount of help in emergencies to people they don’t know, especially when they’re part of an in-group.”

Strange things happen to our brains when we’re in a crowd we’ve chosen to be part of, says Templeton. We don’t just feel happier and more confident, we also have a lower threshold of disgust. This is why festivalgoers will happily share drinks (and by dint of their proximity, sweat) with strangers, or Hajj pilgrims will share the sometimes bloody razors used to shave their heads. In a crowd, we feel safer from harm.

If we now have a better grasp of the complexity of crowd dynamics, the core truth about them is relatively simple: they have the potential to magnify both the good and bad in us. The loss of self in a crowd can lead to unthinkable violence, just as it can ecstatic transcendence. What is striking is that, in recent decades, the latter has troubled the British establishment every bit as much as the former.

‘The open crowd is the true crowd,” wrote Elias Canetti in his 1960 book Crowds and Power – “the crowd abandoning itself freely to its natural urge for growth”, rather than those hemmed in by authorities, limited in shape and size. The Sermon on the Mount, he writes, was delivered to an open crowd. The obsequious flock, the brainwashed cult, the army marching in lock-step, is a world away from a fluid, democratic, sometimes anarchic congregation of the people. These open crowds have become harder to find, and harder to keep open.

Contemporary Britain’s idea of the crowd was formed by two explosions in unruly mass culture at the end of the last century. First, by 70s and 80s football fandom and its manifold sins, and the avoidable tragedy of Hillsborough – a tragedy created by the authorities’ views of the crowd as animalistic thugs, a fear and loathing that permeated the media, police, political class and football authorities. And second, by the acid house explosion and rave scene of the late 80s and early 90s, a subcultural surge of illegal or at least illicit “free parties” in fields and warehouses across the country. Both cultures flourished in spite of widespread media demonisation, both fought the law – and in both cases, the law won. Things have never been the same since for people who wish to assemble on their own terms.

The policing, containment and enclosure of “free” raves is particularly instructive, suggesting that the authorities fear a happy crowd as much as a pitchfork-carrying one. For the novelist Hari Kunzru, reflecting on his 90s youth a few years ago, approaching the site of a rave, feeling “the bass pulsing up ahead, the excitement was almost unbearable. A mass of dancers lifting up like a single body … [an] ecstatic fantasy of community, a zone where we were networked with each other, rather than with the office switchboard.”

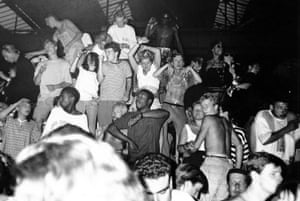

An acid house party in Berkshire in 1989. Photograph: Rex/Shutterstock

The culmination of the rave era, and the beginning of its end, was the epochal 1992 Castlemorton Common festival, a week-long, outdoor free party in Worcestershire, with numbers in excess of 20,000. Writing about it in the Evening Standard, Anthony Burgess summed up the establishment mood, railing against “the megacrowd, reducing the individual intelligence to that of an amoeba”. One man’s escapist fantasy of community is another’s vision of civilisational collapse, and the Thatcher-into-Major-era junta of the tabloid press, police, landowners and the Conservative party made it their business to disperse rave’s congregation of squatters, dropouts, drug-takers, hippies, hunt saboteurs, anti-road protesters and travellers.

In 1994, parliament passed the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act, which outlawed any open air, night-time public congregation around amplified music. “For this purpose,” the act specified, “‘music’ includes sounds wholly or predominantly characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats.” Any ambiguity about the target of the legislation was wiped away during the House of Lords debate on the bill. The Conservative deputy leader of the House, the hereditary peer Earl Ferrers, suggested an amendment “which would catch a rave party but would not also catch a Pavarotti concert, a barbecue or people having a dance in the early hours of the evening”. I do hope, replied another, that they would not risk jailing Pavarotti under the new legislation.

For the ravers, what had begun as a transcendent celebration turned into a question of the right to assemble in the first place. Before the bill passed into law, three elegiac “Kill the Bill” protest-parties took place in 1994, drawing tens of thousands, and culminating in October when bare-chested, dreadlocked protesters shook the gates of Downing Street to a soundtrack of whistles, cheers and repetitive beats. In archival video from that day, a protester clambers to the top of the gates and sits there nonchalantly smoking a fag, while police in short-sleeved shirts look on in horror. It is a telling time capsule, because it is hard to imagine any crowd of protesters getting this close to No 10 ever again.

The culmination of the rave era, and the beginning of its end, was the epochal 1992 Castlemorton Common festival, a week-long, outdoor free party in Worcestershire, with numbers in excess of 20,000. Writing about it in the Evening Standard, Anthony Burgess summed up the establishment mood, railing against “the megacrowd, reducing the individual intelligence to that of an amoeba”. One man’s escapist fantasy of community is another’s vision of civilisational collapse, and the Thatcher-into-Major-era junta of the tabloid press, police, landowners and the Conservative party made it their business to disperse rave’s congregation of squatters, dropouts, drug-takers, hippies, hunt saboteurs, anti-road protesters and travellers.

In 1994, parliament passed the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act, which outlawed any open air, night-time public congregation around amplified music. “For this purpose,” the act specified, “‘music’ includes sounds wholly or predominantly characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats.” Any ambiguity about the target of the legislation was wiped away during the House of Lords debate on the bill. The Conservative deputy leader of the House, the hereditary peer Earl Ferrers, suggested an amendment “which would catch a rave party but would not also catch a Pavarotti concert, a barbecue or people having a dance in the early hours of the evening”. I do hope, replied another, that they would not risk jailing Pavarotti under the new legislation.

For the ravers, what had begun as a transcendent celebration turned into a question of the right to assemble in the first place. Before the bill passed into law, three elegiac “Kill the Bill” protest-parties took place in 1994, drawing tens of thousands, and culminating in October when bare-chested, dreadlocked protesters shook the gates of Downing Street to a soundtrack of whistles, cheers and repetitive beats. In archival video from that day, a protester clambers to the top of the gates and sits there nonchalantly smoking a fag, while police in short-sleeved shirts look on in horror. It is a telling time capsule, because it is hard to imagine any crowd of protesters getting this close to No 10 ever again.

Police bust a warehouse party circa 1997. Photograph: PYMCA/Universal Images Group/Getty

The Criminal Justice Act killed the free party scene, and like Hillsborough, its legacy is still felt to this day. In fact, it was only the beginning of a series of restrictions on free assembly. The past 25 years have been a challenging time for crowds, thanks to the rise of surveillance technology and privatisation of public space. During the 1990s, 78% of the Home Office crime prevention budget was spent on implementing CCTV – and a further £500m of public money was spent on it between 2000 and 2006. London became the most surveilled city in the world for a time, and even today no city outside China has more CCTV per head.

The explosion of CCTV is just one way the 21st-century city hampers the freedom of the crowd. Urban regeneration programmes are designed to channel us efficiently towards work and the shops – spaces built for Homo economicus, human beings interacting transactionally, rather as social citizens. What look like potential meeting grounds for crowds in the modern British city are often mirages: regeneration zones such as Spinningfields in Manchester, Liverpool One and More London have replaced genuine public spaces with privately owned public spaces. These are patrolled by security guards and underwritten by private rules and regulations, whereby the owners are perfectly entitled to ban gatherings and political protests, and move along whoever they like, whenever they like.

In 2011, when Occupy London attempted to set up camp in Paternoster Square, outside the London Stock Exchange, they were blocked by police barricades, enforcing an emergency high court injunction that established that the land was indeed private property. This was odd, the Observer’s architecture critic Rowan Moore wrote at the time, “as almost every architectural statement, planning application, and press release, in the protracted redevelopment of Paternoster Square, described this ‘private land’ as ‘public space’.”

If the average British city has undergone huge transformations since the Criminal Justice Act, then so have the people in it. Crowd behaviour in the 21st century has been conditioned by the new devices at our fingertips as much as the changing ground beneath our feet, or the laws that govern their movement. In his prescient 2002 book Smart Mobs, the critic Harold Rheingold identified new types of crowds that were able to act in concert even before they had met. He predicted a “social tsunami” to come from the next wave of mobile telecoms, pointing to the mass SMS chains in Manila that were used to coordinate the protests that overthrew the Philippine president Joseph Estrada in 2001.

While alienation and isolation are certainly hallmarks of modern life, when a crowd is needed, it springs into life. The 2009 Iran green revolution, the 2011 Arab Spring, the Occupy movement, the Spanish indignados and the 2013 Gezi Park protests in Turkey – all of these “movements of the squares” saw physical public space unexpectedly replenished with fresh, angry crowds that had established many of their initial networks and political education via the internet. “Online inspiration, offline perspiration”, as one slogan of the time put it.

These digitally enhanced tactics took over British streets in the winter of 2010, when student and anti-cuts protesters came out against the Conservative-Lib Dem coalition’s austerity policies and tripling of tuition fees. The police responded with the controversial crowd-control tactic of kettling – essentially imprisoning people outdoors between lines of riot police, without access to food, water, toilets, warm clothing or medical assistance, for hours at a time.

Kettling worked against the student protesters on several fronts, dampening their spirits, disincentivising future protests, riling up some to violence and thus delivering the government the PR victory they needed. “Is not the point of a kettle that it brings things to the boil?” David Lammy MP asked Theresa May, then the home secretary, at the time. But it also radicalised many of them, precisely because they had had their freedom to move restricted, pushing them to direct action tactics in defiance of the tactics proposed by the leaders of the National Union of Students.

The Criminal Justice Act killed the free party scene, and like Hillsborough, its legacy is still felt to this day. In fact, it was only the beginning of a series of restrictions on free assembly. The past 25 years have been a challenging time for crowds, thanks to the rise of surveillance technology and privatisation of public space. During the 1990s, 78% of the Home Office crime prevention budget was spent on implementing CCTV – and a further £500m of public money was spent on it between 2000 and 2006. London became the most surveilled city in the world for a time, and even today no city outside China has more CCTV per head.

The explosion of CCTV is just one way the 21st-century city hampers the freedom of the crowd. Urban regeneration programmes are designed to channel us efficiently towards work and the shops – spaces built for Homo economicus, human beings interacting transactionally, rather as social citizens. What look like potential meeting grounds for crowds in the modern British city are often mirages: regeneration zones such as Spinningfields in Manchester, Liverpool One and More London have replaced genuine public spaces with privately owned public spaces. These are patrolled by security guards and underwritten by private rules and regulations, whereby the owners are perfectly entitled to ban gatherings and political protests, and move along whoever they like, whenever they like.

In 2011, when Occupy London attempted to set up camp in Paternoster Square, outside the London Stock Exchange, they were blocked by police barricades, enforcing an emergency high court injunction that established that the land was indeed private property. This was odd, the Observer’s architecture critic Rowan Moore wrote at the time, “as almost every architectural statement, planning application, and press release, in the protracted redevelopment of Paternoster Square, described this ‘private land’ as ‘public space’.”

If the average British city has undergone huge transformations since the Criminal Justice Act, then so have the people in it. Crowd behaviour in the 21st century has been conditioned by the new devices at our fingertips as much as the changing ground beneath our feet, or the laws that govern their movement. In his prescient 2002 book Smart Mobs, the critic Harold Rheingold identified new types of crowds that were able to act in concert even before they had met. He predicted a “social tsunami” to come from the next wave of mobile telecoms, pointing to the mass SMS chains in Manila that were used to coordinate the protests that overthrew the Philippine president Joseph Estrada in 2001.

While alienation and isolation are certainly hallmarks of modern life, when a crowd is needed, it springs into life. The 2009 Iran green revolution, the 2011 Arab Spring, the Occupy movement, the Spanish indignados and the 2013 Gezi Park protests in Turkey – all of these “movements of the squares” saw physical public space unexpectedly replenished with fresh, angry crowds that had established many of their initial networks and political education via the internet. “Online inspiration, offline perspiration”, as one slogan of the time put it.

These digitally enhanced tactics took over British streets in the winter of 2010, when student and anti-cuts protesters came out against the Conservative-Lib Dem coalition’s austerity policies and tripling of tuition fees. The police responded with the controversial crowd-control tactic of kettling – essentially imprisoning people outdoors between lines of riot police, without access to food, water, toilets, warm clothing or medical assistance, for hours at a time.

Kettling worked against the student protesters on several fronts, dampening their spirits, disincentivising future protests, riling up some to violence and thus delivering the government the PR victory they needed. “Is not the point of a kettle that it brings things to the boil?” David Lammy MP asked Theresa May, then the home secretary, at the time. But it also radicalised many of them, precisely because they had had their freedom to move restricted, pushing them to direct action tactics in defiance of the tactics proposed by the leaders of the National Union of Students.

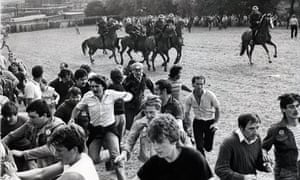

Mounted police drive their horses into protesters during student demonstrations in London in December 2010. Photograph: Leon Neal/AFP/Getty Images

Academic Hannah Awcock attended the 2010 protests as a student, and now lectures on the history of protest at the University of Central Lancashire. She explained that throughout history, from the 1866 Hyde Park suffrage riots to the student demos, protest crowds have often pushed to go further than their organisers, or the authorities, will allow for. And yet, as febrile as the atmosphere around Brexit and austerity has been in the nine years since the student protests and London riots, large protests have appeared calmer, on the face of it at least. In the UK, “that really aggressive and confrontational policing that emerged post-9/11 seems to have diminished now,” Awcock said. “Maybe it’s because the protests themselves are less radical, but it’s also because there’s also been a turn towards more subtle methods of policing crowds, techniques like increased surveillance and intelligence gathering.”

The changes to crowd policing in the past decade owe a great deal to behind-the-scenes policy work by crowd psychologists. Clifford Stott has worked with police and football authorities for many years to discourage heavy-handed policing. One turning point, he told me, was the 2011 Liberal Democrat conference in Sheffield, where South Yorkshire police trialled Stott’s recommendations. Unlike Brighton, Liverpool, Birmingham or Manchester, the city was not used to hosting conferences for a party of government, and substantial student and anti-austerity protests were expected. In preparation, police established a new “dialogue unit” of Police Liaison Teams (PLTs) in blue tabards, recruiting individuals to move among the crowd talking to them, rather than policing in numbers from the outside.

“What we found was that these dialogue units were policing the police,” said Stott. “They were stopping unnecessary interventions. The PLTs were reassuring the commanders that an intervention wasn’t needed.” Instead of riot cops wading in, de-escalation and crowd self-regulation took over. Since then, Stott said, this approach has become more common. “Where the police have these capacities for dialogue and communication, there’s less disorder. It’s that simple.”

According to Ch Insp Melita Worswick of Greater Manchester police, this is part of a broader shift in crowd policing in the UK – away from the notion of enforcing “public order” towards an emphasis on public safety. “It’s really important to have the right people communicating with crowds,” she says. “This is about building on policing with consent, and knowing that if we don’t manage that right, it could result in disorder.” It’s also about learning to step back, rather than aggressively intervening at the first opportunity. “Sometimes taking no action is the right way,” says Worswick. It’s an approach that police in Glasgow have put into action for recent matches between Rangers and Celtic. Following advice from academics, they will now allow fans to jeer at each other for a while, because they know that’s part of the ritual, and won’t intervene unless it starts to get violent. Up to a point, at least, they trust the crowd members to self-regulate.

While this sounds like progress, the reality does not always match the rhetoric. Even Extinction Rebellion, which initially attempted to cultivate a friendly relationship with the police, and sought mass arrest as a tactic – later decried the Met’s “over-reach characterised by systematic discrimination, routine use of force, intimidation and physical harm” in hundreds of cases last year. Even more recently, the Met’s use of Covid-19 social-distancing legislation to make arrests at Sunday’s Black Lives Matter protest in London suggests that many elements in the police remain unwilling to step back from the crowd.

In place of the open crowd, nowadays we have come to understand a congregation of people primarily as a money-making opportunity. There is no greater evidence of the attenuated, monetised nature of the 21st-century crowd than the rise of the events industry. Events, in themselves, are of course not new inventions. But there are events, dear boy, and then there are Events: usually sponsored, probably with an admission fee, probably with a range of media partners, good for city-branding, good for tourism, orderly, pre-agreed, surveilled and dispersed at the agreed time. They have become an integral part of the contemporary city, and the reimagining of its citizens as income-generating instruments.

London & Partners, the public-private partnership set up by Boris Johnson in 2011 to promote the capital, estimates that event leisure tourism contributed £2.8bn to the city’s economy in 2015 alone, £644m of which was from overseas “events tourists”. Increasingly, people come not for the UK per se, but the things happening in it. Chief among these are sporting events, which generate more than 70% of major events-related spending in London (music is some way behind). Amid huge fanfare in the past few years, a growing number of major international NBA, NFL and MLB games have come to London. According to London & Partners, 250,000 people have attended “NFL on Regent Street”, which isn’t even an American Football game, just a promotional event for the idea of one.

Academic Hannah Awcock attended the 2010 protests as a student, and now lectures on the history of protest at the University of Central Lancashire. She explained that throughout history, from the 1866 Hyde Park suffrage riots to the student demos, protest crowds have often pushed to go further than their organisers, or the authorities, will allow for. And yet, as febrile as the atmosphere around Brexit and austerity has been in the nine years since the student protests and London riots, large protests have appeared calmer, on the face of it at least. In the UK, “that really aggressive and confrontational policing that emerged post-9/11 seems to have diminished now,” Awcock said. “Maybe it’s because the protests themselves are less radical, but it’s also because there’s also been a turn towards more subtle methods of policing crowds, techniques like increased surveillance and intelligence gathering.”

The changes to crowd policing in the past decade owe a great deal to behind-the-scenes policy work by crowd psychologists. Clifford Stott has worked with police and football authorities for many years to discourage heavy-handed policing. One turning point, he told me, was the 2011 Liberal Democrat conference in Sheffield, where South Yorkshire police trialled Stott’s recommendations. Unlike Brighton, Liverpool, Birmingham or Manchester, the city was not used to hosting conferences for a party of government, and substantial student and anti-austerity protests were expected. In preparation, police established a new “dialogue unit” of Police Liaison Teams (PLTs) in blue tabards, recruiting individuals to move among the crowd talking to them, rather than policing in numbers from the outside.

“What we found was that these dialogue units were policing the police,” said Stott. “They were stopping unnecessary interventions. The PLTs were reassuring the commanders that an intervention wasn’t needed.” Instead of riot cops wading in, de-escalation and crowd self-regulation took over. Since then, Stott said, this approach has become more common. “Where the police have these capacities for dialogue and communication, there’s less disorder. It’s that simple.”

According to Ch Insp Melita Worswick of Greater Manchester police, this is part of a broader shift in crowd policing in the UK – away from the notion of enforcing “public order” towards an emphasis on public safety. “It’s really important to have the right people communicating with crowds,” she says. “This is about building on policing with consent, and knowing that if we don’t manage that right, it could result in disorder.” It’s also about learning to step back, rather than aggressively intervening at the first opportunity. “Sometimes taking no action is the right way,” says Worswick. It’s an approach that police in Glasgow have put into action for recent matches between Rangers and Celtic. Following advice from academics, they will now allow fans to jeer at each other for a while, because they know that’s part of the ritual, and won’t intervene unless it starts to get violent. Up to a point, at least, they trust the crowd members to self-regulate.

While this sounds like progress, the reality does not always match the rhetoric. Even Extinction Rebellion, which initially attempted to cultivate a friendly relationship with the police, and sought mass arrest as a tactic – later decried the Met’s “over-reach characterised by systematic discrimination, routine use of force, intimidation and physical harm” in hundreds of cases last year. Even more recently, the Met’s use of Covid-19 social-distancing legislation to make arrests at Sunday’s Black Lives Matter protest in London suggests that many elements in the police remain unwilling to step back from the crowd.

In place of the open crowd, nowadays we have come to understand a congregation of people primarily as a money-making opportunity. There is no greater evidence of the attenuated, monetised nature of the 21st-century crowd than the rise of the events industry. Events, in themselves, are of course not new inventions. But there are events, dear boy, and then there are Events: usually sponsored, probably with an admission fee, probably with a range of media partners, good for city-branding, good for tourism, orderly, pre-agreed, surveilled and dispersed at the agreed time. They have become an integral part of the contemporary city, and the reimagining of its citizens as income-generating instruments.

London & Partners, the public-private partnership set up by Boris Johnson in 2011 to promote the capital, estimates that event leisure tourism contributed £2.8bn to the city’s economy in 2015 alone, £644m of which was from overseas “events tourists”. Increasingly, people come not for the UK per se, but the things happening in it. Chief among these are sporting events, which generate more than 70% of major events-related spending in London (music is some way behind). Amid huge fanfare in the past few years, a growing number of major international NBA, NFL and MLB games have come to London. According to London & Partners, 250,000 people have attended “NFL on Regent Street”, which isn’t even an American Football game, just a promotional event for the idea of one.

The plaza in front of City Hall in London, a privately owned and carefully controlled public space. Photograph: Steven Watt/Reuters

Where there are crowds, there are consumers, and in the absence of state support, commercial sponsorship (itself rebranded as “partnership”) tracks the events industry’s every move. Last year, the capital played host to the Virgin Money London Marathon, the Prudential RideLondon, the Guinness Six Nations and the EFG London Jazz Festival. Meanwhile, Pride in London somehow managed to rack up 73 “partners” in 2019, from headline sponsors Tesco to PlayStation, the Scouts, the London Stock Exchange, Revlon and Foxtons, amid criticisms that the politics has been drained out of it in favour of corporate “pinkwashing”.

It’s hard to refute the argument that the more carefully planned and managed a large event is, the safer it is for those inside it, and the more the crowd will enjoy it. Not only do you minimise the risk of injury or potential trouble, but everyone – not least the most vulnerable – benefits when you have accessibility for people with mobility issues, the right number of toilets, the right number of exits, the right transport access, good sightlines, food and water and childcare facilities. And a reasonable argument is often made by organisers of cultural festivals that sponsors pay for these things, and pay for events such as Notting Hill Carnival, Pride and Mela to stay free, and accessible to all. But it’s hard not to wonder if something is being lost along the way, in an era when venture capital-backed music video platform Boiler Room receives Arts Council funding to broker Notting Hill Carnival sponsorship deals and live-stream its intimate hedonism to the world; or popular, long-standing free community festivals such as south London’s Lambeth Country Show suddenly have a heavy security presence, prompting outrage and boycotts.

Where there are crowds, there are consumers, and in the absence of state support, commercial sponsorship (itself rebranded as “partnership”) tracks the events industry’s every move. Last year, the capital played host to the Virgin Money London Marathon, the Prudential RideLondon, the Guinness Six Nations and the EFG London Jazz Festival. Meanwhile, Pride in London somehow managed to rack up 73 “partners” in 2019, from headline sponsors Tesco to PlayStation, the Scouts, the London Stock Exchange, Revlon and Foxtons, amid criticisms that the politics has been drained out of it in favour of corporate “pinkwashing”.

It’s hard to refute the argument that the more carefully planned and managed a large event is, the safer it is for those inside it, and the more the crowd will enjoy it. Not only do you minimise the risk of injury or potential trouble, but everyone – not least the most vulnerable – benefits when you have accessibility for people with mobility issues, the right number of toilets, the right number of exits, the right transport access, good sightlines, food and water and childcare facilities. And a reasonable argument is often made by organisers of cultural festivals that sponsors pay for these things, and pay for events such as Notting Hill Carnival, Pride and Mela to stay free, and accessible to all. But it’s hard not to wonder if something is being lost along the way, in an era when venture capital-backed music video platform Boiler Room receives Arts Council funding to broker Notting Hill Carnival sponsorship deals and live-stream its intimate hedonism to the world; or popular, long-standing free community festivals such as south London’s Lambeth Country Show suddenly have a heavy security presence, prompting outrage and boycotts.

Perhaps this is too pessimistic. The 21st-century domestication of the crowd does not in itself snuff out its power. The experience of being part of a crowd can still change us in all manner of unexpected ways. If one thing should be retained from academics’ debunking of the myth of the crowd as a single beast with one brain and a thousand limbs, it is precisely that the diversity of the individuals within the crowd is what makes it so vital.

Far from behaving as one, everyone has different cooperation thresholds for participation, and there are some who by their nature will always be the first in the pool. For better or worse, crowds empower more shy or conservative people to do what they might not have done otherwise: to pronounce their political beliefs or proclaim their sexual orientation in public, to sing about their heartfelt feelings for Sergio Agüero, to occupy a bank, to throw a brick, to fight with strangers, to dance to Abba in the concourse of a major intercity railway station.

Being a crowd member is not a muscle that will atrophy through lack of use – our knack for it, and need for it, has a much longer history than the months we will be required to keep our physical distance. The desire to be part of the crowd is a part of who we are, and it will not be dispersed so easily.

Saturday, 23 December 2017

Modi Ji, thank you for ending my has-been status

by Mani Shankar Aiyer in NDTV.com

Spokespersons for the Bharatiya Janata Party have been asserting on TV screens that I should have taken the government’s permission before hosting an old Pakistani friend of mine to dinner. Why should I seek anyone’s permission to host a dinner party — even if that friend is a Pakistani?

Why cannot I invite friends and colleagues to talk about Pakistan with a distinguished Pakistani? Why must I toe Modi’s line on Pakistan? What gives the government a monopoly of national opinion on our neighbour? Does anyone who does not believe that the Prime Minister is the nation’s sole fount of wisdom become liable to the charge of treachery? Do I not have a right to privacy? Do my guests not have such a right?

The BJP responds that this was not just some dinner party, it amounted to sleeping with the enemy. Indeed, the Prime Minister has darkly hinted that I was hiring a contract killer (“supari”) to get him. Invoking a fake Facebook post, he slyly let slip that the dinner was a “secret” conclave to hatch a “conspiracy” with the Pakistanis to make — horror of horrors — a Gujarati Muslim the chief minister of Gujarat.

Utter rubbish, total balderdash, but a nasty move to establish a salience between Pakistan and Indian Muslims to polarise a crucial election.

Well, I don’t consider Muslims or Pakistanis my enemies, especially a Pakistani Muslim like Khurshid Kasuri, who I have known since we were 20-year-old undergraduates at the same Cambridge college some 56 years ago. It was a friendship that was renewed when the founder-President of the BJP, and then Janata Party Foreign Minister of India, Atal Behari Vajpayee, chose me to be the first-ever Consul General of India in Karachi (1978-82).

Did he choose me to go to Karachi to spew at the Pakistanis? Atal Behari-ji would invariably take his seat in the House whenever I rose to speak on Pakistan. For unlike the present incumbent, he was not paranoid about Pakistan. A true democrat, he was interested in understanding other perspectives on that country.

I flew to Islamabad in Dec 1978 from the home of our ambassador in Abu Dhabi, Hamid Ansari, a brilliant diplomat and an engaging companion with whom I had served a little earlier in Brussels. He was among my closest friends in the Foreign Service and I appointed him chairman of the Oil Diplomacy Committee when I was Petroleum Minister. Destiny had kissed him on the brow to rise for 10 long years (2007-2017) to the second-highest constitutional position in our land: Vice President and Chairman of the Rajya Sabha.

Invaluable in his penetrating insights into the Pak psyche, he has guided me over the years through the maze of Pakistan’s domestic politics. He introduced me to his wife’s relatives in Karachi. Hamid Ansari was second only to Doctor-sahib (former prime minister Dr Manmohan Singh) among the distinguished guests at my dinner.

The morning after I reached Islamabad to be briefed by my Ambassador before taking up my new assignment, I heard the Ambassador speaking on the phone to Khurshid Kasuri. I slipped him a note on which I had scribbled that Khurshid was an old friend of mine. He passed on the phone to me, and I could hear the joy in Khurshid’s voice as he welcomed me to Pakistan, insisting that I proceed to Karachi only after visiting Lahore.

A tempting invitation

That was a tempting invitation as I was born in Lahore. I agreed, subject to Khurshid driving me straight from the airport to my old home at 44, Lakshmi Mansions.

Khurshid agreed and my Ambassador indulgently let me take that circuitous route to my new posting.

That Ambassador, Katyayani Shankar Bajpai, was no soft-heart like me. He has always had a hard, tough understanding of Pakistan, untouched by any of the starry-eyed romanticism that tinges my view of that country. He was at the time in almost daily touch with Barrister Khurshid Kasuri, monitoring developments in the then ongoing Lahore High Court trial of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto.

Now nearly 90 years old, Ambassador K. Shankar Bajpai was another of my valued guests.

On my landing in Lahore, Khurshid Kasuri picked me up and drove me straight to the apartment where my family had lived till Partition, now taken over by a medical doctor who had been a student in London while Khurshid and I were cutting our academic teeth in Cambridge.