'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label civil. Show all posts

Showing posts with label civil. Show all posts

Friday, 4 August 2023

Monday, 12 June 2023

Sunday, 4 December 2022

Saturday, 3 September 2022

Sunday, 11 July 2021

Friday, 18 June 2021

Has the blackbox of UAPA finally been opened?

Pratap Bhanu Mehta in The Indian Express

Student activists Natasha Narwal, Devangana Kalita and Asif Iqbal Tanha outside Tihar prison, after a court ordered their immediate release in the north-east Delhi riots "conspiracy" case, in New Delhi, Thursday, June 17, 2021. (PTI Photo)

The orders passed by Justices Siddharth Mridul and Anup J Bhambhani, granting bail to Asif Tanha, Devangana Kalita, and Natasha Narwal, have opened up the black box of the UAPA (Unlawful Activities Prevention Act) jurisprudence. The UAPA had become the black box of Indian jurisprudence for a number of reasons. First, as the orders note, the definition of “terrorism” in Section 15 of the UAPA is vague, and has been used as a licence to classify all kinds of infractions as terrorist. This order will put more spotlight on how individuals are charged under the provisions of the UAPA.

It requires that the state show why the alleged crimes or infractions should not be dealt with by laws dealing with conventional offences under the IPC or other relevant laws. It also helpfully points out that a simple law-and-order problem in a state should not be equated with a terrorist problem. By making a clear distinction that the former is a state subject, and the latter a Union subject under lists one and two, the order, potentially, also has implications for federalism in matters of law enforcement.

Second, it lays down at least a general standard for when a case might be made for being charged under the UAPA. In particular, this order insists that the allegations made against the accused must be backed up by facts, must pertain to acts undertaken by them as individuals, and must be specifically framed. This goes counter to the recent trend where sometimes chargesheets rely as much on speculation as fact, invoke circumstantial considerations about the broad political context rather than acts committed by individuals, and are framed vaguely.

Third, this order opens up the important issue of bail. The UAPA, broadly interpreted, can be a Kafkaesque law when it comes to bail. It prohibits granting bail if there are reasonable grounds for believing that the prosecution’s case might be prima facie true. The problem with this is that often the prosecution’s version was accepted without serious cross-examination. But the Supreme Court had put the defendants in an even more Catch-22 situation, by effectively prohibiting courts from engaging in a substantial examination of the merits of a case during the bail hearings. This order reiterates the fact that courts still have a lot of room to subject the government’s case to scrutiny even in bail hearings. They can examine, as this order has done, how the law has been applied, and they can even look into evidentiary questions. There is a little bit of a conceptual challenge here, though. The court rightly looked into the nature of the evidence presented by the state in this case, and effectively demolished it. Based on the considerations put forward in these orders, it is difficult to imagine another court being able to uphold the state’s case for prosecution.

The question is, if a higher court hears a bail hearing, how can its orders be crafted in a way that does not prejudge the outcome of a full-blown trial. In this case, the charges and evidence were patently absurd. It is difficult to see how the court could have come to any other conclusion. But when higher courts hear bail hearings and grant relief based on the demolition of the prosecution’s case, what implications does it have for a full trial? This case gives a good prudential reason for the state not to oppose bail in many circumstances precisely for this reason: Opposing bail opens up the case to greater scrutiny without the context of a full trial. This is an interesting conceptual issue.

This order is also a welcome effort to prevent our civil liberties from being swallowed up by the black hole of state power. The UAPA is also a problematic law because it attacks the presumption of innocence. The Supreme Court is becoming wobbly on as fundamental a right as habeas corpus, the state is construing the expression of thought as a crime, ordinary protest is being suppressed or criminalised, bail is being routinely denied, and the state is actively targeting dissenters. In this context, the reiteration of some common sense principles is very welcome: It provides some relief and hope for constitutional wisdom to prevail. Hopefully, it will empower more judges to do their duty.

The orders passed by Justices Siddharth Mridul and Anup J Bhambhani, granting bail to Asif Tanha, Devangana Kalita, and Natasha Narwal, have opened up the black box of the UAPA (Unlawful Activities Prevention Act) jurisprudence. The UAPA had become the black box of Indian jurisprudence for a number of reasons. First, as the orders note, the definition of “terrorism” in Section 15 of the UAPA is vague, and has been used as a licence to classify all kinds of infractions as terrorist. This order will put more spotlight on how individuals are charged under the provisions of the UAPA.

It requires that the state show why the alleged crimes or infractions should not be dealt with by laws dealing with conventional offences under the IPC or other relevant laws. It also helpfully points out that a simple law-and-order problem in a state should not be equated with a terrorist problem. By making a clear distinction that the former is a state subject, and the latter a Union subject under lists one and two, the order, potentially, also has implications for federalism in matters of law enforcement.

Second, it lays down at least a general standard for when a case might be made for being charged under the UAPA. In particular, this order insists that the allegations made against the accused must be backed up by facts, must pertain to acts undertaken by them as individuals, and must be specifically framed. This goes counter to the recent trend where sometimes chargesheets rely as much on speculation as fact, invoke circumstantial considerations about the broad political context rather than acts committed by individuals, and are framed vaguely.

Third, this order opens up the important issue of bail. The UAPA, broadly interpreted, can be a Kafkaesque law when it comes to bail. It prohibits granting bail if there are reasonable grounds for believing that the prosecution’s case might be prima facie true. The problem with this is that often the prosecution’s version was accepted without serious cross-examination. But the Supreme Court had put the defendants in an even more Catch-22 situation, by effectively prohibiting courts from engaging in a substantial examination of the merits of a case during the bail hearings. This order reiterates the fact that courts still have a lot of room to subject the government’s case to scrutiny even in bail hearings. They can examine, as this order has done, how the law has been applied, and they can even look into evidentiary questions. There is a little bit of a conceptual challenge here, though. The court rightly looked into the nature of the evidence presented by the state in this case, and effectively demolished it. Based on the considerations put forward in these orders, it is difficult to imagine another court being able to uphold the state’s case for prosecution.

The question is, if a higher court hears a bail hearing, how can its orders be crafted in a way that does not prejudge the outcome of a full-blown trial. In this case, the charges and evidence were patently absurd. It is difficult to see how the court could have come to any other conclusion. But when higher courts hear bail hearings and grant relief based on the demolition of the prosecution’s case, what implications does it have for a full trial? This case gives a good prudential reason for the state not to oppose bail in many circumstances precisely for this reason: Opposing bail opens up the case to greater scrutiny without the context of a full trial. This is an interesting conceptual issue.

This order is also a welcome effort to prevent our civil liberties from being swallowed up by the black hole of state power. The UAPA is also a problematic law because it attacks the presumption of innocence. The Supreme Court is becoming wobbly on as fundamental a right as habeas corpus, the state is construing the expression of thought as a crime, ordinary protest is being suppressed or criminalised, bail is being routinely denied, and the state is actively targeting dissenters. In this context, the reiteration of some common sense principles is very welcome: It provides some relief and hope for constitutional wisdom to prevail. Hopefully, it will empower more judges to do their duty.

But it is premature to be optimistic about the direction of civil liberties in India. It is a matter of great relief that the trial court has finally released the accused. But prior to that, their release was delayed by a day on the grounds that their address had not been verified. If the state could not verify the address of someone they had in their custody for a year, you don’t know whether to laugh or cry. It is almost as if the authorities decided to enact a parody version of their impunity. But there is no escaping this fact. The order is an indictment of the Delhi Police and its masters in the Ministry of Home Affairs. In any civilised democracy, heads would have rolled. Instead, what we will get is an aggressive appeal by the state. We can only hope the Supreme Court will not let the cause of liberty down again.

We also know that landmark orders often have very little effect on the state or the culture of the judiciary. They sometimes work in high-profile cases. Sometimes they are a reflection of conscientious judges doing their duty as these judges seem to have done. But more often than not, they have been a flash in the pan that allow us to hold on to the illusion that the judiciary will at some point dispense justice. Will this order, by the power of its example, have an implication for the travesty of justice being enacted in the Bhima Koregaon cases, and the fate of Sudha Bharadwaj and Anand Teltumbde? Just yesterday this paper carried the story on the front page of Mohammed Ilyas and Mohammed Irfan, who were acquitted of UAPA-related charges after nine years, seven of which they spent in jail having had four bail applications turned down. It is a reminder that the pathologies of the UAPA are not specific to particular political parties, but were hardwired into the system.

This bail order has opened up the black box of UAPA jurisprudence. It is well reasoned, without histrionics, and full of constitutional common sense. But whether this order will be sufficient to wipe off the recent black marks against the judiciary remains to be seen.

We also know that landmark orders often have very little effect on the state or the culture of the judiciary. They sometimes work in high-profile cases. Sometimes they are a reflection of conscientious judges doing their duty as these judges seem to have done. But more often than not, they have been a flash in the pan that allow us to hold on to the illusion that the judiciary will at some point dispense justice. Will this order, by the power of its example, have an implication for the travesty of justice being enacted in the Bhima Koregaon cases, and the fate of Sudha Bharadwaj and Anand Teltumbde? Just yesterday this paper carried the story on the front page of Mohammed Ilyas and Mohammed Irfan, who were acquitted of UAPA-related charges after nine years, seven of which they spent in jail having had four bail applications turned down. It is a reminder that the pathologies of the UAPA are not specific to particular political parties, but were hardwired into the system.

This bail order has opened up the black box of UAPA jurisprudence. It is well reasoned, without histrionics, and full of constitutional common sense. But whether this order will be sufficient to wipe off the recent black marks against the judiciary remains to be seen.

Monday, 29 March 2021

Saturday, 18 February 2017

The scandal that rocked Bikram yoga

We’re 15 minutes into the Monday morning class at Hot 8 Yoga in Beverly Hills. Francesca Asumah, one of the most sought-after instructors in California, is putting 48 perspiring humans through a sequence of 26 poses and two breathing exercises popularised by the celebrity yogi Bikram Choudhury. The temperature is a sapping 40C. Sweat slicks over yoga mats. Beautiful bodies melt into shapes that seem beyond the realm of ordinary human geometry.

Asumah’s class, titled A Dance With The Ancients, falls somewhere between gym session and sermon. “You must learn to love yourself, guys!” she encourages us in a northern English accent (she’s half-Ghanaian, half-English, and from Manchester). “If everyone loves themselves, then the whole world will be loved. And beware false gurus! Gurus are middlemen. We are all born in the temple. If anyone claims to be your guru, run a mile, people!”

The message has a special charge in this room. This is the home of what the yogis in my class call “the Bikram community-in-exile”: people who used to be at the heart of the movement, and who say they suffered horrendous abuse in their pursuit of yogic enlightenment. Sweating next to me is Minakshi “Micki” Jafa-Bodden, 48, former legal adviser for the Bikram yoga company. She wants me to appreciate the hold that these poses have before she will talk any further: “You can’t understand me unless you understand Bikram yoga.” And it’s just as well Jafa-Bodden remains devoted to the 26 poses: last month, Los Angeles county court gave her control of the entire global empire.

***

If you’re not up on your chakras and pranayamas, you could be forgiven for thinking that “Bikram” is a term for a kind of hot yoga performed by celebrities and Hollywood types in unsanitary conditions. It is that: Andy Murray credits it with helping his “fitness and mental strength”; Serena Williams and David Beckham are said to be fans. But it is also a sequence of moves that takes its trademarked name from one man. At his early 2010s peak, the pony-tailed, waxed-chested image of Bikram Choudhury adorned the walls of around 650 licensed Bikram yoga studios across the world. For many, he was a spiritual leader as well as the inventor of an exercise class.

Little is known of Choudhury’s early life. Born in Kolkata in 1946, he claimed to have been invited to America by Richard Nixon, and to have taught yoga to the Beatles and Nasa astronauts. He once told a class that he invented the disco ball.

What is certain is that his yoga gave his students something they found life-changing. Asumah first went to a Bikram-affiliated studio in London in 2000. “I immediately saw the benefit of it,” she says. “At a normal yoga class, you do whatever poses the teacher feels like teaching you. Our form of yoga is different. I’m 64. My quality of life is so joyful and I know it’s because of the yoga.” She believes the 26 poses contain a “sacred geometry” that has been handed down from “the ancients”. Choudhury also claimed his form of yoga was more rigorous and authentic than westernised forms preaching peace and love.

Micki Jafa-Bodden: ‘You can’t understand me unless you understand Bikram yoga.’ Photograph: Steve Schofield/The Guardian. Hair and makeup: Ricardo Ferisse

Choudhury first set up a studio in a basement in Beverly Hills. From the mid-1970s onwards, he drew in a celebrity clientele, including Michael Jackson, Jeff Bridges, Shirley MacLaine, Barbra Streisand and Raquel Welch. His classes, heated to a regulation 40C (designed to mimic conditions in Kolkata), offered a combination of constructive hazing, cosmic wisdom and pantomime eccentricity. He would wear Speedos and issue bizarre commands; in 2011, a writer for GQ magazine went to a class and reported him telling a student, “You, Miss Teeny-Weeny Bikini! Spread your legs!” He loathed the colour green and banned people from wearing it. He had never seen carpet until he arrived in America, and believing it represented the height of luxury had all his studios carpeted, hygiene be damned.

Initially, Choudhury asked for donations and slept on the floor of his studio; but as his celebrity grew, so did his material demands. He claimed he had trademarked his sequence and filed aggressive lawsuits to prevent former students from adapting his 26 moves (including a suit accusing Raquel Welch of stealing his sequence for her exercise book). In 2012, a California federal judge dismissed Choudhury’s attempt to trademark his sequence, ruling that a series of yoga poses cannot be copyrighted. As a New York studio owner, Greg Gumucio, whom Choudhury tried to shut down, told ABC news: “It’s kind of like if Arnold Schwarzenegger said, ‘I’m going to do five bench presses, six curls, seven squats, call it Arnold’s Work, and nobody can show that or teach that without my permission.’”

Choudhury’s most reliable stream of revenue was his twice-yearly teacher-training sessions, where up to 400 students would pay around £10,000 to undergo nine weeks of intensive yoga to become certified Bikram instructors. These earned Choudhury a personal fortune estimated at $75m, including a fleet of 43 luxury cars.

I saw it as my forever job. It allowed me to combine my love of yoga with the legal and business side

Benjamin Lorr, who wrote a book-length study of Choudhury called Hell-Bent in 2012, attended a training course in Las Vegas in 2009 and found himself drawn to Choudhury, despite describing him as “clearly a buffoon”. By the third evening, Choudhury had told the class that he launched Michael Jackson’s career, cured Janet Reno’s Parkinson’s disease, was once best friends with Elvis, and had experienced “72 hours of marathon sex, where my partner has 49 orgasms. I count.” (He married his wife Rajashree, herself a certified Bikram instructor, in 1984.)

But for Lorr, Choudhury’s ridiculousness only added to his charisma. He had the quality of being present in the moment. “You see it with Donald Trump, too – it’s this unscripted responsiveness,” Lorr tells me. “Bikram has an incredible ability to zoom in on specific people, combined with an ability to act as if he’s being true to himself.” And then there’s what Lorr calls the “volume game”. “When there are 380 people in a room cheering, you begin to wonder: ‘Why am I the only who’s sitting out of this?’ So you find yourself clapping and cheering, despite the fact that what he just said was moronic, or homophobic, or racist, or offensive.”

It was at these training camps – held in large hotel resorts – that Choudhury’s worst alleged abuses took place; there are now six separate suits working their way through the California courts, ranging from sexual harassment to rape. Jafa-Bodden is so far the only woman who has managed to defeat Choudhury in court: last month, a Los Angeles county jury awarded her a total of $6.8m in damages for a range of charges including unlawful dismissal and sexual harassment.

But recovering her damages has not been easy. Choudhury has since fled to India; his fleet of cars has vanished. When cornered by a TV journalist from HBO’s Real Sports at a teacher-training camp near Mumbai last October, Choudhury insulted his accusers and claimed that 5,000 women a day would line up to have sex with him: “Why do I have to harass women? People spend $1m for one drop of my sperm. Are you that dumb to believe those trash?” he said on camera. He also boasted that “this yoga is worse than cocaine. You can get rid of cocaine, but once you’re used to this yoga, you can’t stop.”

Back in March 2011, when Jafa-Bodden first stepped into Choudhury’s Beverly Hills HQ, she was convinced she had just landed her dream job. She was born in Assam, India, received her legal training in Britain, and had spent her career moving between Europe, India and the Caribbean, working in international litigation. She was introduced to Choudhury by his Indian lawyer, Som Mandal. Choudhury insisted that she start right away, and he and Rajashree helped her with her immigration papers, going so far as to choose (and furnish) a flat for her.

As a single mother with a six-year-old daughter, it seemed the perfect opportunity. “I saw it as my forever job,” Jafa-Bodden recalls. “It allowed me to combine my love of yoga and spirituality with the legal and business side of things. I was ready to take on a bigger role, and I also thought I was coming to work for a family-oriented company.”

Jafa-Bodden has the supple movements and clear complexion that comes from taking three or four hot yoga classes a week. She combines a disarming friendliness with a lawyer’s caution. She insists on meeting me twice before she will answer my questions: once for afternoon tea, once for yoga. When I am finally granted a formal interview at her attorneys’ offices in Santa Monica, she welcomes me wearing a camouflage jacket with the words “TRUST THE UNIVERSE” spelled in diamante on the back.

Her first inkling that something wasn’t right came when Choudhury and Rajashree invited her to their mansion in Beverly Hills a couple of days after she took up her position. “It was like the lair of a Bollywood villain. It was very showy and elaborate, not quite what I was expecting from a yoga guru.” Still, she says, he was on his best behaviour. “I’ve dealt with high-net-worth individuals in all sorts of countries, and my read on Bikram was just that he was eccentric.”

Meanwhile, in her day job, she found “operational dysfunction: a total co-mingling of personal and corporate assets”. Choudhury had a tendency not to settle his hotels bills, so her first task was to fight Marriott hotels over an unpaid sum of $1.8m. Choudhury also liked to use the company account as a personal credit card. But initially Jafa-Bodden saw this as an opportunity; she felt she had the necessary expertise to straighten out the business. It was only when a lawsuit from a former trainee named Pandhora Williams landed on her desk that she realised the extent of her problems.

***

The Bikram teacher-training courses centre on two mass 90-minute hot yoga sessions a day interspersed with anatomy seminars, spiritual lectures and rote learning of 45 pages of copyrighted Bikram dialogue. Choudhury likes to conduct the evening class from a throne with one attendant typically brushing his hair and another massaging his legs. Francesca Asumah attended a course in spring 2002. “He walked in and everybody started jumping around and cheering,” she recalls. “Because I’m English, and we don’t really do cults, I didn’t really understand what was going on. But everybody was worshipping him.”

Choudhury teaching in Beverly Hills, California in 1982. Photograph: Joan Adlen Photography/Getty Images

She was 49, and believes her “difficult” attitude led to her being shunned by Choudhury’s inner circle; the typical attendees were aged 22 to 35 and seemed more impressionable. “There were a lot of really beautiful bodies, all dressed in tight shorts and bikinis.”

In the evenings, Choudhury would invite his favourites to watch Bollywood movies with him. Anyone who fell asleep would be woken up; the ordeal would often go on until 3am. The first yoga session of the next day was 8am, and was often accompanied by vomiting, fainting and weeping. Nonetheless, despite the hardships, most students agreed it was worth it. “There were a few people who would exchange looks and raise their eyebrows,” Asumah says. “But you’d spent your £10,000. And the yoga’s good. And you’d just try to bear what you can.”

The case that landed on Jafa-Bodden’s desk in May 2011, the suit from Pandhora Williams, related to a training session at the Town and Country Resort in San Diego the previous autumn. Williams’ lawyers alleged that Choudhury had invited the class to lie down in savasana (corpse pose) whereupon he launched into a homophobic rant, announcing that all gay people should be put on an island and “left to die of Aids”. After the class, Williams had asked, “Bikram, why are you preaching hate? Yoga is supposed to be about love.” She alleges that he replied, “We don’t sell love here, bitch,” then told an assistant, “Get that black bitch out of here. She’s a cancer.” Williams was ejected from the course – and Choudhury refused to refund her $10,900 fee. So she sued for racial discrimination.

“I realised that if half of this was true, we were facing a very serious situation,” Jafa-Bodden tells me now. She conducted internal investigations and challenged Choudhury on his behaviour. She found him unremorseful. “He would pick on someone in the crowd. If someone got up to go to the toilet, he would say, ‘Where are you going? To change your tampon?’ He uses profanities, he’s antisemitic, he’s homophobic. He’ll say things like, ‘Blacks don’t get my yoga.’ And once he starts on his tirade of profanity, he doesn’t stop. Once he’s picked on you, then you’ve had it for the entire class.”

Why did no one stand up to him? “There’s very little you can do. He’s up there on a podium, he’s miked up, and it’s really hot.” Many trainees feared losing the thousands of dollars they had already spent on the fees. “Their livelihood depends on putting up with it. The problem was that Bikram had set things up in such a way that, without his continued patronage, you can’t teach anywhere else. So some of his victims would come back to his training and just try to take precautions.”

Once people have bought into any cult, there’s no rational way you can change their minds

Further allegations followed. Jafa-Bodden was required to read the manuscript of Lorr’s book Hell-Bent for libel, but found nothing actionable. The book’s allegations of sexual impropriety opened the floodgates. “Once people have bought into any cult, there’s no rational way you can change their minds – it has to be an emotional change,” Lorr tells me. “It was only when people started to see how much hurt he had caused that they began to change their minds.”

In 2013, a series of rape allegations were made. A former student, Sarah Baughn, claimed that Choudhury had sexually assaulted her at a 2008 training camp, pleading, “I am dying. I can feel myself dying. I will not be alive if someone doesn’t save me.” A Canadian student, Jill Lawler, sued Choudhury for a litany of charges, including sexual assault, gender discrimination, sexual harassment and sexual battery; she was 18 when the alleged crimes took place. Another student, Maggie Genthner, alleged that he raped her twice, forcing her legs into yoga postures and laughing at her.

Jafa-Bodden says she repeatedly challenged Choudhury on his behaviour, but he simply expected her to make the allegations go away. “At the outset, he expected me to be submissive,” she says. “He told me he was a god who could do whatever he wanted and that I was ‘stupid and too westernised’.”

Jafa-Bodden claims that, on one occasion, Choudhury held a meeting in his presidential suite and encouraged her to join him in bed. “He would tell me to go and ‘shut up’ the witnesses,” Jafa-Bodden says. “One woman sent a Facebook message saying that Bikram had tried to put his penis in her mouth – a horrific allegation. I went to Bikram and said, ‘What is this?’ And he said, ‘I thought we’d taken care of that bitch in Hawaii.’” After she told him he wasn’t allowed to bring trainees to his bedroom, he mocked her in front of a class: “He stood up on his podium and said: ‘My lawyer tells me I can’t have a girl in my room. So I’m now going to have two!’”

Bikram Choudhury assists actress Carol Lynley at his yoga studio in Beverly Hills, California. Photograph: Joan Adlen Photography/Getty Images

Jafa-Bodden became depressed, which she says has led to ongoing problems with anxiety. “My entire life revolved around Bikram and his yoga. It was like living in a parallel universe,” she says. She considered leaving the country, but was trapped. “I never received my pay cheque on time or for the full amount agreed. I was dependent on Bikram for everything, including my work visa, my apartment, my car. My cellphone was connected to his and my every move was monitored. It would have been very risky to flee without a well-thought-out exit strategy. He would say they’d revoke my green card, so I’d be deported back to India.”

Finally, in February 2013, she was subpoenaed to testify in the Williams case, which sent Choudhury “crazy”. “He said ominously, ‘Well, we’ll just tell them we don’t know where you are.’ I was so frightened.” The next month, he terminated her contract. With no car and little money, she moved with her daughter to a guesthouse until she was able to find a small one-bedroom apartment.

Jafa-Bodden eventually turned to her former adversary, Carla Minnard, the Californian attorney who had subpoenaed her in the Williams lawsuit. “My motto is, where there is darkness let there be light,” Jafa-Bodden says now. “I feel I have to show my daughter that you have to fight through the fear.” She sued Choudhury for unfair dismissal and sexual harassment.

An Irish former employee, Sharon Clerkin (herself allegedly dismissed for becoming pregnant), testified at Jafa-Bodden’s trial that Choudhury continued to demean women at teacher training, calling them “bitches” and boasting about allegations that were then surfacing on social media (“it’s good for business”).

The jury unanimously ruled that Jafa-Bodden had been subject to sexual harassment, nonpayment of wages, wrongful dismissal and a number of further charges. In December, with Choudhury refusing to return to the US, the judge ordered that the income from his studio franchises and his intellectual property be handed over to Jafa-Bodden. Last month, she filed a separate suit against Rajashree, who divorced Choudhury in 2016 and remains in the Beverly Hills mansion. (At the time of the divorce, it was ruled that she wasn’t required to pay damages in any pending or future cases; Jafa-Bodden and her lawyers are challenging that verdict.)

To date, there have been no criminal charges brought against Choudhury; all the women are pursuing civil cases. Choudhury denied all of Pandhora Williams’ claims before they settled out of court in May 2013, and has dismissed the other allegations as “lies lies lies”. However, he has repeatedly refused to return to the US; last month he violated a court order to complete a video deposition in the Clerkin case. A few weeks later, his attorney in that case quit, saying Choudhury was no longer cooperating or paying his bills.

Responding to a Guardian request for comment, Bikram’s Indian lawyer, Som Mandal, last week denied all the allegations. He said that Bikram had hired new lawyers and would be appealing the verdict in the Jafa-Bodden case.

For her part, Jafa-Bodden says she is less interested in the money than in seeing justice done: “It’s about accountability.” Meanwhile, many Bikram studio owners are removing photographs of Choudhury and distancing themselves from their former guru. There are around 30 yoga studios that carry the Bikram name in the UK, and many are rebranding: Bikram Yoga North, West, City and Primrose Hill in London now go under the name Fierce Grace.

Outside the US, Choudhury continues to advertise training camps: his next teacher-training session in Acapulco, Mexico, this April is again priced at about £10,000. “That’s so concerning for us,” Jafa-Bodden says. “Innocent and impressionable young trainees might be going to these camps in jurisdictions where there may not be as many protections.”

You’d understand it if Jafa-Bodden never wanted to step inside another yoga studio again, but she remains devoted to the series of 26 poses. “It must seem mystifying to someone who is not into Bikram yoga,” she laughs, “but I do actually think yoga is the answer.” She credits Asumah with seeing her through her worst moments.

Asumah herself has every reason to leave yoga behind. Her first husband died of a heart attack after taking a yoga class in Ibiza, and she blames Choudhury for the failure of her second marriage. Yet she has forgiven him. “If you spoke to me when I was in the depths of hurt, I’d have spoken differently. But he didn’t make me bitter. The highest form of love is forgiving the unforgivable.”

All of which leaves Jafa-Bodden with a dilemma. She is effectively president of Bikram Inc. But there is a serious issue with the name: in the process of de-Bikramisation, she wants to separate the yoga from the man who created it – not so easy when it’s a brand known the world over (most devotees don’t make the connection with the megalomaniac in Speedos). And she still remains devoted to the Bikram community. Can she rebuild the business as something new? As Asumah says, “Sometimes you get a rotten branch, and you have to cut it off, but it doesn’t mean the whole tree’s gone.”

Saturday, 29 October 2016

Friday, 6 May 2016

The lies binding Hillsborough to the battle of Orgreave

Ken Capstick in The Guardian

Police covered up their attacks on striking miners. And they used the same tactics after the football tragedy.

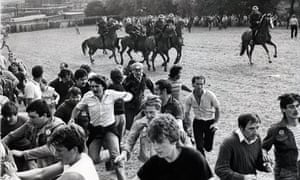

‘For those of us who were there when the ranks of police suddenly opened up and launched a cavalry charge, it felt like civil war.’ Photograph: Photofusion/Rex

Just eight miles separates the patch of ground on the outskirts of Sheffield where Orgreave coking plant once stood from Hillsborough stadium, where 96 people were unlawfully killed on 15 April 1989. To those of us involved in the miners’ strike in south Yorkshire in the 1980s, the so-called “battle of Orgreave” and Britain’s worst football disaster have always been linked.

It was a glorious summer’s day on 18 June 1984. With my son and other mineworkers, I set off for Orgreave to take part in a mass demonstration to try to stop coke being moved from the plant to the steelworks at Scunthorpe.

The miners were in a jovial mood, dressed in T-shirts and plimsolls. To save on petrol most of us travelled four or five to a car. We had been on strike for more than three months, had very little money and relied on the £2 picketing money from the union to pay for petrol. Our destination was to be the scene of one of the bloodiest battle grounds in Britain’s industrial history.

We went to Orgreave to fight to save our industry from what has since been revealed, following the release of cabinet papers in January 2014, as a government plan to kill off the coal mining industry, close 75 pits at a cost of approximately 75,000 jobs, and destroy the National Union of Mineworkers.

The battle of Orgreave was a one-sided contest, as miners suddenly found themselves facing not a police force, but a paramilitary force dressed in riot gear, wielding long truncheons, with strategically placed officers with dogs, and a cavalry charge reminiscent of a medieval battleground.

For those of us who were there when the ranks of police suddenly opened up and launched the charge on horseback, it felt like civil war. Miners had no defence other than to try and outrun the horses. Furthermore, we had to run uphill. Many miners were caught and battered to the ground with truncheons, then outnumbered by police on foot before being roughly handled as they were arrested. Those of us who made it to the top of the hill found refuge in a supermarket or in the nearby mining village.

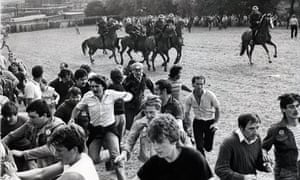

‘Following the battle, 95 miners were charged with riot, an offence which can carry a life sentence.’ Photograph: Mike Forster/Associated News/Rex

No one died at Orgreave, but it was clearly the intention of the police to create what felt like a life-threatening situation. The police faced no threat from the miners at Orgreave that warranted such a violent response, but it was obvious to those present that the police knew they could act with impunity.

Following the battle, 95 miners were charged with riot, an offence which could carry a life sentence. Gareth Peirce, one of the defending solicitors in the abortive trial that followed, wrote in the Guardian in 1985: “Orgreave … revealed that in this country we now have a standing army available to be deployed against gatherings of civilians whose congregation is disliked by senior police officers. It is answerable to no one; it is trained in tactics which have been released to no one, but which include the deliberate maiming and injuring of innocent persons to disperse them, in complete violation of the law.”

Miners' strike: IPCC considers unredacted Orgreave report

I wasn’t in court when the prosecution of the Orgreave miners was thrown out because the evidence did not stack up. But the trial revealed the way police would collaborate and coordinate evidence in order to get convictions or cover up the truth. In this sense, Orgreave can be seen as a dry run for what happened after the Hillsborough disaster in 1989. Had the South Yorkshire force not been allowed to get away with what they did at Orgreave, perhaps Hillsborough would never have happened.

As the Hillsborough inquest verdicts have shown, we cannot have an unaccountable police force charged with upholding the rule of law but immune to it. We need to know which politicians or officials gave such immunity to the police, if it was given.

Only a full public inquiry into Orgreave will get at the truth, an inquiry to which all documents must be revealed in unredacted form. This inquiry would not just be in the interests of the miners injured on that day, and in the interests of their families. It would be in all our interests, because we all need to understand how a police force came to believe it was a law unto itself. If we don’t, we risk creating the conditions in which another Hillsborough or Orgreave could happen.

In 1985 the miners shouted from the rooftops, but we weren’t heard. Ignored by the media, many gave up. What happened at Orgreave was not a human tragedy on the same scale as Hillsborough. But now, thanks to the tremendous campaign by the Hillsborough families who lost loved ones, and who refused to give up their fight for justice, we have the chance to discover the truth about what happened at Orgreave too.

Police covered up their attacks on striking miners. And they used the same tactics after the football tragedy.

‘For those of us who were there when the ranks of police suddenly opened up and launched a cavalry charge, it felt like civil war.’ Photograph: Photofusion/Rex

Just eight miles separates the patch of ground on the outskirts of Sheffield where Orgreave coking plant once stood from Hillsborough stadium, where 96 people were unlawfully killed on 15 April 1989. To those of us involved in the miners’ strike in south Yorkshire in the 1980s, the so-called “battle of Orgreave” and Britain’s worst football disaster have always been linked.

It was a glorious summer’s day on 18 June 1984. With my son and other mineworkers, I set off for Orgreave to take part in a mass demonstration to try to stop coke being moved from the plant to the steelworks at Scunthorpe.

The miners were in a jovial mood, dressed in T-shirts and plimsolls. To save on petrol most of us travelled four or five to a car. We had been on strike for more than three months, had very little money and relied on the £2 picketing money from the union to pay for petrol. Our destination was to be the scene of one of the bloodiest battle grounds in Britain’s industrial history.

We went to Orgreave to fight to save our industry from what has since been revealed, following the release of cabinet papers in January 2014, as a government plan to kill off the coal mining industry, close 75 pits at a cost of approximately 75,000 jobs, and destroy the National Union of Mineworkers.

The battle of Orgreave was a one-sided contest, as miners suddenly found themselves facing not a police force, but a paramilitary force dressed in riot gear, wielding long truncheons, with strategically placed officers with dogs, and a cavalry charge reminiscent of a medieval battleground.

For those of us who were there when the ranks of police suddenly opened up and launched the charge on horseback, it felt like civil war. Miners had no defence other than to try and outrun the horses. Furthermore, we had to run uphill. Many miners were caught and battered to the ground with truncheons, then outnumbered by police on foot before being roughly handled as they were arrested. Those of us who made it to the top of the hill found refuge in a supermarket or in the nearby mining village.

‘Following the battle, 95 miners were charged with riot, an offence which can carry a life sentence.’ Photograph: Mike Forster/Associated News/Rex

No one died at Orgreave, but it was clearly the intention of the police to create what felt like a life-threatening situation. The police faced no threat from the miners at Orgreave that warranted such a violent response, but it was obvious to those present that the police knew they could act with impunity.

Following the battle, 95 miners were charged with riot, an offence which could carry a life sentence. Gareth Peirce, one of the defending solicitors in the abortive trial that followed, wrote in the Guardian in 1985: “Orgreave … revealed that in this country we now have a standing army available to be deployed against gatherings of civilians whose congregation is disliked by senior police officers. It is answerable to no one; it is trained in tactics which have been released to no one, but which include the deliberate maiming and injuring of innocent persons to disperse them, in complete violation of the law.”

Miners' strike: IPCC considers unredacted Orgreave report

I wasn’t in court when the prosecution of the Orgreave miners was thrown out because the evidence did not stack up. But the trial revealed the way police would collaborate and coordinate evidence in order to get convictions or cover up the truth. In this sense, Orgreave can be seen as a dry run for what happened after the Hillsborough disaster in 1989. Had the South Yorkshire force not been allowed to get away with what they did at Orgreave, perhaps Hillsborough would never have happened.

As the Hillsborough inquest verdicts have shown, we cannot have an unaccountable police force charged with upholding the rule of law but immune to it. We need to know which politicians or officials gave such immunity to the police, if it was given.

Only a full public inquiry into Orgreave will get at the truth, an inquiry to which all documents must be revealed in unredacted form. This inquiry would not just be in the interests of the miners injured on that day, and in the interests of their families. It would be in all our interests, because we all need to understand how a police force came to believe it was a law unto itself. If we don’t, we risk creating the conditions in which another Hillsborough or Orgreave could happen.

In 1985 the miners shouted from the rooftops, but we weren’t heard. Ignored by the media, many gave up. What happened at Orgreave was not a human tragedy on the same scale as Hillsborough. But now, thanks to the tremendous campaign by the Hillsborough families who lost loved ones, and who refused to give up their fight for justice, we have the chance to discover the truth about what happened at Orgreave too.

Sunday, 3 April 2016

Freedom from triple talaq: Goa shows the way

S A Aiyar in the Times of India

A step forward in gender justice is the Supreme Court’s admission of the petition of a Muslim woman, Shayara Bano, pleading that polygamy and oral triple talaq —saying talaq thrice in succession — violate fundamental human rights, and hence are unconstitutional. Indian politics has always sabotaged gender justice for Muslim women. But the Supreme Court does not have to woo Muslim vote banks, and can be objective.

The mullahs are livid, of course. Kamal Farooqi of the All India Muslim Personal Law Board says, “This will mean direct interference of the government in religious affairs as Sharia religious law is based on the Quran and Hadith, and its jurisprudence is strong as far as Islam is concerned. It will be against the constitutional right to religious freedom.”

Sorry, but the Constitution makes it very clear that freedom of religion does not override fundamental rights, and does not bar reforms of traditional religious practices. Sharia law may permit the stoning to death of a woman for adultery, but our secular laws ban that. Sharia law may call for the amputation of fingers or hand of a thief, but not our secular laws. Sharia law may prohibit interest on loans, but Muslims giving or taking loans are subject to laws on interest payments.

Now, religious minorities have been allowed to continue with traditional personal laws on matters like marriage and inheritance. Jawaharlal Nehru had the courage to amend Hindu personal law, outlawing polygamy and providing female rights to inherit property, divorce, and remarry. Alas, he funked similar reforms for Muslims, leaving Muslim women as oppressed and subjugated as ever.

A Directive Principle of the Constitution says the state shall endeavour to secure for citizens a uniform civil code throughout India. This has never been implemented. Muslim conservatives are dead opposed. Religious objections apart, they say a civil code will become a form of Hindu oppression.

Some enlightened Muslims have urged modernization of Islamic personal law. But secular political parties know that conservatives control the Muslim vote, and woo them by saying Muslims themselves must take the initiative on reforms. In effect, secular parties have thrown Muslim women to the wolves in search of votes.

The BJP is the only party backing a common civil code, but its strong anti-Muslim instincts lead one to suspect it is keener on bashing Muslims than ending gender oppression.

Right fight: Politicians who say Muslims don’t want personal law reforms are thinking only of Muslim men

Oral triple talaq permits a man to utter three times that he is divorcing his wife, and she is at the mercy of his whims. In our travels through India, my late wife Shahnaz often spoke to Muslim women, who invariably said that one of the greatest injustices they faced was the ever-present threat of triple talaq. The same fears are expressed by Shayara Bano in her Supreme Court petition. “They (women) have their hands tied while the guillotine of divorce dangles perpetually ready to drop at the whims of their husbands who enjoy undisputed power.”

Women constitute half the Muslim population, but have no voice because of male subjugation. Politicians who say Muslims don’t want to reform personal laws are thinking only of male Muslims, not female Muslims. When oppressive Muslim laws keep women under the thumbs of men, they cannot express their true wants and have to follow male orders. Conservative Muslims have historically discouraged female education, keeping women disempowered and unable to strike out on their own.

If a referendum with secret voting is held among Muslim women, they will surely opt to abolish triple talaq and polygamy. But they are not given the chance. So they remain disempowered and subjugated,with the shameful complicity of secular parties claiming to represent universal rights.

The 2012 Committee on the Status of Women has made gender recommendations covering all religions. It seeks to ban triple talaq and polygamy. It seeks stronger provisions for maintenance payments to women and children (these can currently be cut off if a divorcee is “unchaste”). The Supreme Court should heed the report.

Forget the propaganda that a common civil code will mean Hindu oppression. Goa is the only state that disallows personal laws of all religions. It has a uniform civil code — with a few exceptions not relevant to Muslims — based on Portuguese colonial laws. Goa’s mullahs sought to extend Muslim personal law to Goa after liberation from Portuguese rule, but happily were foiled by the Goa Muslim Women’s Associations and Muslim youth activists. Muslims account for 8.3% of Goa’s population, and are a prosperous community. The civil code has not oppressed Goan Muslims or forcibly Hinduised them.

Any fear that a uniform civil code will mean Hindu oppression of Muslims will be exposed as groundless if India simply follows Goa’s example. The Supreme Court should point all political parties in Goa’s direction.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)