'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Wednesday, 3 July 2024

Monday, 3 June 2024

Friday, 21 July 2023

A Level Economics 51: Tragedy of the Commons

1. Importance of Property Rights in a Market System:

Property rights refer to the legal ownership and control that individuals or entities have over assets, resources, and goods. In a market system, property rights play a fundamental role in facilitating efficient resource allocation and promoting economic growth. Here's why property rights are essential to the functioning of a market system:

Incentive to Invest and Innovate: Secure property rights provide individuals and businesses with the assurance that they can enjoy the fruits of their investments and innovations. When people know they will reap the benefits of their efforts, they are incentivized to invest, take risks, and innovate, leading to increased productivity and economic growth.

Clear Ownership and Transferability: Property rights allow for clear ownership and transferability of assets. This enables individuals to buy, sell, or trade property, goods, and resources in the marketplace, promoting efficient allocation based on supply and demand.

Resource Allocation: Property rights facilitate the efficient allocation of resources by providing a framework for individuals to decide how to use and manage their property. Resources flow to their most valued uses as people make decisions based on their preferences and economic incentives.

Encouraging Specialization and Trade: With secure property rights, people can specialize in the production of goods and services they are most efficient at producing. This specialization leads to increased productivity and fosters trade, where individuals can exchange their products or services for other goods they desire.

Enforcing Contracts: Property rights are essential for enforcing contracts and agreements. When people trust that their rights will be protected, they are more likely to engage in transactions and trade with others, fostering economic cooperation.

2. Tragedy of the Commons and Market Failure: The tragedy of the commons is a situation where a commonly held, shared resource (such as a grazing pasture, fishery, or air and water quality) is overused and depleted because no individual or group has exclusive property rights over the resource. This leads to market failure and inefficiency due to the following reasons:

Lack of Exclusivity: When no one owns exclusive rights to a resource, there is no incentive for any individual to protect or preserve it. Each person acts in their self-interest, using the resource to their advantage without considering its long-term sustainability.

Overconsumption: As more individuals use the shared resource to maximize their own benefits, it leads to overconsumption and depletion of the resource beyond its sustainable capacity. This creates a situation where the resource is eventually exhausted or damaged, negatively affecting everyone.

Negative Externalities: The tragedy of the commons results in negative externalities, where the actions of one individual negatively impact others. For example, overfishing in an unregulated fishery leads to reduced fish populations, affecting the livelihoods of other fishermen.

Inefficiency: The overexploitation of the commons creates inefficiencies in resource allocation. Instead of being allocated to its most valued uses, the resource is depleted and underutilized, leading to lost economic opportunities and social welfare.

Market Failure and the Role of Government:

The tragedy of the commons is an example of market failure because the free market cannot efficiently allocate the shared resource when property rights are not well-defined. In such cases, the government can intervene through regulation, establishing property rights, or implementing policies to address the overuse of the common resource. By creating property rights or setting limits on resource use, the government can incentivize sustainable management and prevent the depletion of shared resources, leading to more efficient resource allocation and improved social welfare.

---Inequities in Property Rights

In modern-day societies, property rights can exhibit inequities that result from various factors and historical developments. These inequities can lead to disparities in access, ownership, and control of property, exacerbating social and economic inequalities. Here are some ways in which inequities in property rights manifest:

Historical Disadvantages: In many countries, historical injustices and discriminatory policies have led to certain groups, such as indigenous populations or marginalized communities, being systematically denied access to land and property ownership. As a result, they face ongoing disadvantages in acquiring and holding property.

Land Concentration: In some regions, a significant portion of land is concentrated in the hands of a small elite, while a large section of the population has limited access to land ownership. This concentration of land ownership can perpetuate economic disparities and limit opportunities for social mobility.

Urban vs. Rural Property Rights: In urban areas, property rights may be better protected and enforced compared to rural regions, where informal or customary land tenure systems prevail. This disparity can lead to greater insecurity and vulnerability for rural communities in terms of land ownership.

Gender Disparities: Women often face discriminatory property laws and cultural norms, which restrict their rights to own and inherit property. These gender disparities can limit women's economic independence and exacerbate gender-based inequalities.

Inheritance Rights*: Inequity in inheritance rights is another aspect of property rights that contributes to social and economic disparities. In some societies, inheritance laws may favor male heirs over female heirs, perpetuating gender-based inequalities in property ownership and limiting financial security for women.

Lack of Legal Recognition: In some countries, certain types of property, such as communal land or informal settlements, may lack legal recognition. This can lead to insecurity of tenure and vulnerability to forced evictions, particularly among vulnerable populations.

Gentrification: In urban areas, gentrification can result in the displacement of long-standing communities due to rising property values and rents. As wealthier individuals move in, property prices increase, making it difficult for existing residents to afford to remain in their neighborhoods.

Addressing these inequities in property rights requires comprehensive policy measures and legal reforms to ensure fair and inclusive access to property ownership and control. Governments can enact laws that protect the rights of marginalized groups, strengthen land tenure systems, and ensure gender equality in property ownership. Additionally, land redistribution programs, affordable housing initiatives, and measures to address gentrification can help promote more equitable property rights.

In conclusion, inequities in modern-day property rights are rooted in historical legacies, discriminatory practices, and inadequate legal protections. Recognizing and addressing these inequities is essential for promoting social justice, economic opportunity, and sustainable development. Governments play a crucial role in enacting policies to protect property rights and promote fair and equitable access to resources for all members of society.

Inequity in inheritance rights is another crucial aspect that contributes to social and economic disparities in property ownership. In many societies, inheritance laws and cultural norms can perpetuate gender-based inequalities and favor certain privileged groups, leading to unequal distribution of wealth and property. Here's how inheritance rights can contribute to inequities in property rights:

Gender Bias: In some countries, inheritance laws may favor male heirs over female heirs, leading to gender-based disparities in property ownership. Women may face limitations in inheriting property, especially in patriarchal societies, which can restrict their economic opportunities and financial security.

Primogeniture: Traditional inheritance systems in some cultures follow primogeniture, where the eldest son inherits the bulk of family property, leaving younger siblings with limited or no inheritance rights. This practice can exacerbate wealth concentration within a specific group, leading to unequal access to resources.

Intestate Succession Laws: When a person dies without a will (intestate), inheritance laws dictate how their property will be distributed among heirs. In some cases, intestate succession laws may not adequately protect the rights of surviving spouses, children, or other dependents, leading to potential injustices.

Wealth Concentration: Inheritance can contribute to the concentration of wealth within certain families or social classes. When large amounts of property and wealth are passed down through generations, it can perpetuate economic disparities and limit opportunities for social mobility.

Informal Inheritance Practices: In many regions, informal inheritance practices may prevail, leaving vulnerable individuals, such as widows, orphans, and disadvantaged groups, without proper legal recognition of their inheritance rights. This lack of formal protection can lead to property dispossession and vulnerability to exploitation.

Addressing inequities in inheritance rights is crucial for promoting social and economic justice. Governments can play a vital role in enacting inheritance laws that promote gender equality, protect the rights of vulnerable groups, and ensure fair distribution of property among heirs. Efforts to promote legal awareness and empower marginalized individuals to claim their inheritance rights are also essential in addressing these inequities.

In conclusion, inheritance rights can significantly impact property ownership and wealth distribution in a society. Addressing the inequities in inheritance laws and cultural norms is essential for promoting equitable access to property, reducing wealth disparities, and ensuring equal economic opportunities for all members of society. Governments must actively work towards creating a fair and inclusive framework that upholds the principles of justice and equality in property rights.

Friday, 16 June 2023

Are Inheritance Laws Good for Capitalism?

The evaluation of inheritance laws and their impact on capitalism can be subjective, and opinions on this matter can vary:

- Supportive of Capitalism:

a) Encouragement of Wealth Accumulation: Inheritance laws can motivate individuals to accumulate wealth and engage in entrepreneurial activities, which are essential for capitalist economies to thrive.

Example: "Inheritance laws incentivize individuals to work hard and invest their time and resources to build wealth, knowing that they can pass it on to future generations."

b) Preserving Family Businesses: Inheritance laws can help maintain and preserve family-owned businesses, which often play a significant role in the capitalist system.

Example: "Inheritance laws allow successful family businesses to continue operating across generations, contributing to economic growth and employment opportunities."

- Challenging for Capitalism:

a) Wealth Concentration and Inequality: Inheritance laws may perpetuate wealth concentration within a few families, potentially leading to income inequality and reduced economic mobility.

Example: "Inheritance laws that allow massive wealth transfers can create a system where the rich become richer, leaving fewer opportunities for others to accumulate wealth."

b) Market Distortions: Inheritance laws can distort market dynamics by providing individuals with resources without necessarily requiring them to contribute actively to the economy. This can hinder the meritocratic principles of capitalism.

Example: "Inheritance laws can result in some individuals having significant advantages in terms of wealth and resources, irrespective of their efforts or abilities."

"It is well enough that people of the nation do not understand our banking and monetary system, for if they did, I believe there would be a revolution before tomorrow morning." - Henry Ford

This quote indirectly touches upon the potential negative consequences of wealth concentration, which can be influenced by inheritance laws. Concentration of wealth and power can lead to societal unrest and disrupt the capitalist system itself.

Overall, the evaluation of inheritance laws in relation to capitalism depends on weighing the advantages of wealth accumulation and business preservation against the challenges of wealth concentration and market distortions. It is important to strike a balance that promotes economic growth, social mobility, and fair opportunities for all individuals within a capitalist framework.

Sunday, 4 December 2022

Monday, 29 March 2021

Thursday, 1 August 2019

Why Marry?

In response to my piece Modern Marriages - For Better or For Worse, an erudite reader asked ‘Why Marry?’ This person also asked whether one could lead a better productive life without marrying? In this piece, this writer will give some views on the matter.

In India, despite all the modernity, sex before marriage and outside marriage is still frowned upon. Until consensual sex becomes as common place as meeting a friend for coffee, there will always be some supporters of marriage.

This also begs the question whether both individuals in a marriage are content with the quantity and quality of sex available?

Another question that arises is whether the absence of sex reduces the productive potential of an individual. I will plead ignorance on this matter too.

The economic rationale for marriage used to be property inheritance. Much has been written about it which I will not revisit. However, in these days of ‘reliable’ paternity tests, the need for marriage to ensure that property goes to the sperm donor’s offspring is obsolete.

Of course, I am of the view that no child should inherit their parents’ property. But there needs a lot of change in societal arrangements for this to happen; something which I don’t think will happen in my lifetime.

What of the children born of a sexual union, whether consensual or accidental? If it is consensual, then the couple should have a plan for raising their child. As for ‘accidental’ children - there shouldn’t be too many due to the availability of many pregnancy termination choices available for women in the market place.

What impact will this have on the population of a society? If trends are to be believed, all over the world where women have shown an upward trajectory in economic independence the rate of population growth has declined significantly. This augurs well even from a climate change perspective as the demand for resources could dwindle with a rapidly declining population.

Could there ever be a time when one would have to exhort women to produce more children? I don’t think that will be ever be necessary in the future, because by the time we reach this Utopia medical technology may enable production of full grown adults. This will also take away the burden of child care from either cohabiting partner leaving them free to pursue their potential.

Thursday, 24 January 2019

How the right tricked people into supporting rampant inequality

Why don’t people rebel? The wonder of decades of rising inequality across the west is how placidly people put up with it. UK wages are still below 2008 levels, a growing sector of jobs are nasty – non-unionised, achingly hard, with workers treated worse, the boot on the employer’s foot despite low unemployment. You might call Brexit a kind of protest – but that can be overdone: the vote was swung largely by comfortable older Tory voters in the shires, led – or misled – by privileged ideologues.

Those on the progressive left have been perplexed that rising social injustice hasn’t led to much sign of the oppressed rising up, either in the ballot box or in protest. New research out on Wednesday from the London School of Economics suggests some explanations – though these will be of precious little comfort. Looking at surveys across the OECD’s 23 developed western countries since the 1980s, Dr Jonathan Mijs of the London School of Economics International Inequalities Institute monitors how, as countries become less equal, attitudes of the majority shift in the wrong direction.

Both rich and poor delude themselves they are ordinary

People come to believe more strongly that their country is a meritocracy where hard work and talent take people to the top. They are less likely to think structural inequalities or birth help or hinder people’s rise. The US, home of the American Dream – the myth that everyone has an equal chance to rise from log cabin to White House – is the most unequal, yet 95% now firmly believe in meritocracy, fewer in structural injustice. The UK, Australia and New Zealand are not far behind, sharing this Anglophone disease, a societal “body dysmorphia”: other European countries are less inclined to justify inequality, though the movement has been in that direction. This is the neoliberal triumph over hearts and minds.

The meritocracy myth comes with other tropes, especially placing the blame on the poor, with decreasing social empathy. Believing people sink through their own fault is the necessary adjunct for proving the mega-wealthy got there by merit alone.

In Britain, where inequality shot through the roof in the mid-80s and has stayed there ever since, we have seen how despising inequality’s losers has been deliberately fostered by governments. The Public and Commercial Services Union representing job centre staff, published a pamphlet this week outlining the decline in support for social security, and those who receive it. Remember the sheer spite of Peter Lilley, Tory social security secretary, in 1992 singing to his party conference a Mikado pastiche of a “little list” of people to be despised: “young ladies who get pregnant just to jump the housing queue” and “benefits offenders” making “bogus claims”. From then on the rightwing press and Benefits Street mockery set the tone of public contempt for anyone in need. Iain Duncan Smith used to send out juicy examples of benefit cheats to selected rightwing newspapers, without government figures showing fraud at just 1.1% of the benefits budget. In 2013, Ipsos Mori found that the public think £24 in every £100 is fraudulently claimed.

Politically, the mystery is why politicians got away with making things unfairer after the lid blew off top earning in the 80s. Now there’s less chance of owning a home, fewer savings, more debt and public services deteriorating. Cedric Brown, the first fat-cat shocker to catch the public eye, rewarded in 1995 for privatising British Gas with a salary of £475,000 (47 times that of his average employee), and a £600,000 incentive deal, comes from more innocent days. FTSE 100 CEOs now earn £4m.

Yet riots are extraordinarily rare – the French have always done it: it’s in their founding revolutionary DNA, and it helps to keep them less unequal than the Anglophones. Fear of revolution in cold war years kept unions strong and boardrooms wary of excess: the mid-70s, famed for union militancy, were the most equal years in British history.

This research suggests that as countries get more unequal people live in greater social isolation, locked within a narrow income group. Their friends and family share the same incomes, segregated by neighbourhood and marry similar partners. Children mix less in socially segregated schools. People no longer see over the high social fences so they don’t know how the other half lives, Mijs finds.

Ignorant of the facts, everyone wrongly places themselves on the income scale closer to the middle. Both rich and poor delude themselves they are ordinary. But telling people the facts doesn’t change their attitudes: increasingly they cling to a moral belief that people rise by merit, sinking for lack of it. Spend time talking to people using food banks or in Citizens Advice Bureaus knocked down by benefit sanctions, and too often you hear people absorbing the blame. “I should have tried harder at school,” is a frequent refrain, as if no other forces were at play. Talk to the mega-rich – I once conducted focus groups of earners up to £10m – and they are wilfully ignorant about their super-privilege, unshakable in believing their superior merit.

The right captured the story, the emotions, the moral framing: social democrats need to seize it back with a narrative of immorality that is more compelling. The British Social Attitudes survey suggests a swing back towards empathy with the swelling numbers of poor – more than £4m children. But still inheritance tax remains the most reviled of all taxes. The right forever try to prove the poor are stupider by nature than the rich, but Professor Steve Jones, celebrated geneticist, when asked about the heritability of intelligence, replies deftly that the most important heritable trait, by miles, is wealth.

Saturday, 22 April 2017

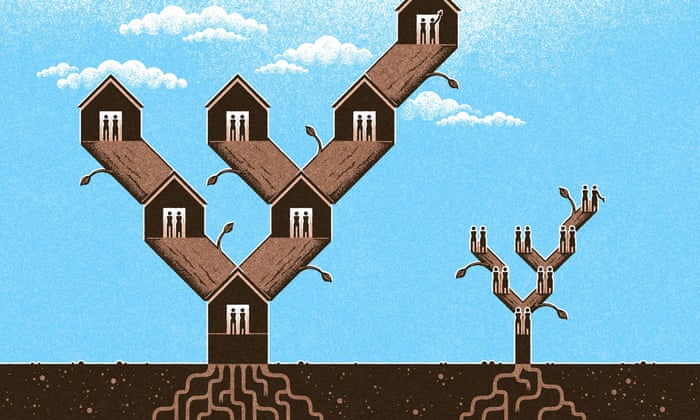

Property feeds the roots of inequality in Britain. Inheritance will entrench it

From my father’s side the treasures included: a stuffed canary; a tiny stuffed crocodile (a gharial, taken from the Ganges); some crested china bought in seaside resorts; and a canteen of excellent cutlery given as a wedding present in 1899 and never taken from its box. On my grandmother’s death, a display cabinet was bought to accommodate this sudden Victorian infusion into our household, which already had a fine little portrait of Rob Roy inherited from my mother’s father, to be followed much later (after a diversion to an aunt and then a cousin) by a wall-clock and a watercolour of a street in Kirkcaldy that looked very pretty from a distance. I’m sure to have forgotten other items – for example, I’m just now remembering the 78rpm discs of Enrico Caruso and Harry Lauder – but basically that was it.

If there was money, there was very little. No property, you see. Neither side of the family had ever owned a house – and so, in terms of material changes to their children’s lives, their deaths were inconsequential. I, on the other hand, do own a house. More than that, I own a house in London. My death, and that of a million like me, will be very consequential.

According to Steve Webb, policy director of the Royal London mutual insurance company, “a wall of housing wealth [is] set to cascade through the generations in the coming years”.

A study published this week by Royal London estimates that roughly £400bn presently tied up in homes owned by people aged 65 to 85 will be handed down to their children and grandchildren. A typical estate of what the study calls this “wealth mountain” is worth between £400,000 and £500,000, to be shared out between four or five children or adult grandchildren and often to be reinvested in property.

The study is based on a YouGov survey of more than 5,600 people covering three generations: the so-called “grandparents generation” of 65- to 85-year-old homeowners; the “sandwich” generation of parents aged 45 to 64, who have living parents from whom they might expect to inherit; and a “children’s” generation of adults aged 25 to 44 who have owner-occupier parents and grandparents.

Surveys are only surveys: caveat emptor. Nevertheless, the report discovers some intriguing differences between generations. While the youngest group believes that their grandparents should spend freely to enjoy their retirement, the grandparents themselves think it right to hoard their money for their grandchildren. Many don’t wait to die. A third of those aged 75 and over had given sizeable sums of money to their grandchildren, a generation that according to the study’s calculations have received a total of £38bn from both their parents and grandparents – often, especially in London and the south-east, to spend on property. And while grandparents tend to act out of a sense of distant benevolence, parents are responding to the “pressure” exerted by their children’s predicaments. The study’s title picks up this theme: Will harassed “baby boomers” rescue Generation Rent?

Earlier this year, the Institute for Fiscal Studies published research on the growth of inheritance as a phenomenon in British life. It showed how less than 40% of the cohort born in the 1930s have received or expect to receive a bequest, while for those born in the 1970s the figure is 75%. Their benefactors are on average much richer. In 2002-3, the household wealth of people aged 80 and over averaged £160,000; 10 years later, thanks mainly to increases in home ownership and house prices, the average had risen to £230,000.

So far, the impact of inheritance on entrenching or heightening inequality has been fairly small – the average inheritance equals only 3% of the other income its recipient can expect to generate in a lifetime. But neither the Royal London nor the IFS study expects that to last. “We are entering an unprecedented era where the older generation is retiring with vast housing wealth,” says the first in its final paragraph. “That wealth is largely being preserved through retirement and will in due course find its way down through the generations. Public policy making needs to take far more account of these very substantial financial flows and perhaps focus more attention on those who are not likely to be the beneficiaries.”

In other words, we are re-entering the world of the Victorian novel, in which suitable marriages, contested wills and misplaced legacies drive the plot, while the poor – the people without lawyers – press their faces against the window of this vigorous, scheming world and merely invite our sympathy.

It wasn’t supposed to happen. “Come with us, then, towards the next decade,” said Margaret Thatcher, winding up her speech to the Conservative party conference in 1985. “Let us together set our sights on a Britain where three out of four families own their home, where owning shares is as common as having a car, where families have a degree of independence their forefathers could only dream about.”

Anyone under the age of 45 is now much less likely to be a homeowner than people of the same age 25 years ago

Two years later the writer Neal Ascherson wrote a prescient column in the Observer that he recalls as “the most popular column I ever wrote … It was greedily read by the yuppie generation – and then fiercely denounced for being wrong.” Foreseeing that soaring house prices meant that London’s middle-class young would inherit many millions when their parents died, Ascherson predicted an “explosion of liquid wealth that would create instant and colossal inequality”: a society with an upper class rich enough to maintain servants, in a “court city” drained of industry that had reverted to the production of luxurious baubles.

Economists pointed out that the cash raised from property sales wouldn’t be “liquid” – it would be sucked up by the inflated cost of the new houses the inheritors moved into – but from today’s vantage point Ascherson’s futurism does not look so wrong. A new super-rich class with butlers and housemaids has moved in, though mainly from overseas rather than Britain, while owner-occupation has become a mirage for growing numbers of the less well-off.

Homeownership today stands just slightly above the rate when Thatcher made her speech: 64% of all households compared with 61% of all households in 1985, having declined from a peak of 71% in 2003. Anyone under the age of 45 is now much less likely to be a homeowner than people of the same age 25 years ago, while the reverse is true of older age groups.

Private renters account for more than 20% of the housing market; in 1985 the figure was 9%. High rents rule out the kind of savings needed for a deposit on a house – with an average price in London equivalent to more than 16 times the average London salary, and 12 and 13 times the mean income of people in their 20s and 30s in prosperous cities such as Cambridge and Brighton. Meanwhile prices, which might be expected to slump amid the economic uncertainty of Brexit, have instead held reasonably steady because the fall in the value of sterling has made them more attractive to international investors.

As the IFS says, these developments mean that inherited wealth is likely to play a more important – I would say crucial – role “in determining the lifetime economic resources of younger generations, with important implications for inequality and social mobility”. What can grammar schools do – supposing they really are agents of social mobility – against this coming weight of money, which will deepen privilege like a coastal shelf? The metaphor is borrowed from Philip Larkin. “They set you up, your mum and dad. They say they mean to, and they do.” For some of us, This Be the Verse.