What did our grandparents leave us? That will depend on who they were and what they possessed, but in my case, not untypical of my generation, it wasn’t very much.

From my father’s side the treasures included: a stuffed canary; a tiny stuffed crocodile (a gharial, taken from the Ganges); some crested china bought in seaside resorts; and a canteen of excellent cutlery given as a wedding present in 1899 and never taken from its box. On my grandmother’s death, a display cabinet was bought to accommodate this sudden Victorian infusion into our household, which already had a fine little portrait of Rob Roy inherited from my mother’s father, to be followed much later (after a diversion to an aunt and then a cousin) by a wall-clock and a watercolour of a street in Kirkcaldy that looked very pretty from a distance. I’m sure to have forgotten other items – for example, I’m just now remembering the 78rpm discs of Enrico Caruso and Harry Lauder – but basically that was it.

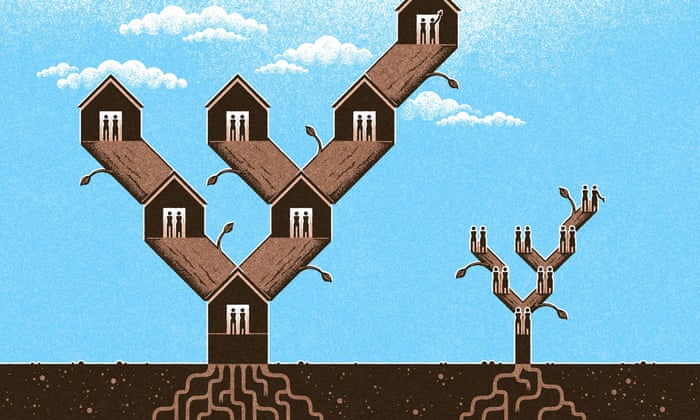

If there was money, there was very little. No property, you see. Neither side of the family had ever owned a house – and so, in terms of material changes to their children’s lives, their deaths were inconsequential. I, on the other hand, do own a house. More than that, I own a house in London. My death, and that of a million like me, will be very consequential.

According to Steve Webb, policy director of the Royal London mutual insurance company, “a wall of housing wealth [is] set to cascade through the generations in the coming years”.

A study published this week by Royal London estimates that roughly £400bn presently tied up in homes owned by people aged 65 to 85 will be handed down to their children and grandchildren. A typical estate of what the study calls this “wealth mountain” is worth between £400,000 and £500,000, to be shared out between four or five children or adult grandchildren and often to be reinvested in property.

The study is based on a YouGov survey of more than 5,600 people covering three generations: the so-called “grandparents generation” of 65- to 85-year-old homeowners; the “sandwich” generation of parents aged 45 to 64, who have living parents from whom they might expect to inherit; and a “children’s” generation of adults aged 25 to 44 who have owner-occupier parents and grandparents.

Surveys are only surveys: caveat emptor. Nevertheless, the report discovers some intriguing differences between generations. While the youngest group believes that their grandparents should spend freely to enjoy their retirement, the grandparents themselves think it right to hoard their money for their grandchildren. Many don’t wait to die. A third of those aged 75 and over had given sizeable sums of money to their grandchildren, a generation that according to the study’s calculations have received a total of £38bn from both their parents and grandparents – often, especially in London and the south-east, to spend on property. And while grandparents tend to act out of a sense of distant benevolence, parents are responding to the “pressure” exerted by their children’s predicaments. The study’s title picks up this theme: Will harassed “baby boomers” rescue Generation Rent?

Earlier this year, the Institute for Fiscal Studies published research on the growth of inheritance as a phenomenon in British life. It showed how less than 40% of the cohort born in the 1930s have received or expect to receive a bequest, while for those born in the 1970s the figure is 75%. Their benefactors are on average much richer. In 2002-3, the household wealth of people aged 80 and over averaged £160,000; 10 years later, thanks mainly to increases in home ownership and house prices, the average had risen to £230,000.

So far, the impact of inheritance on entrenching or heightening inequality has been fairly small – the average inheritance equals only 3% of the other income its recipient can expect to generate in a lifetime. But neither the Royal London nor the IFS study expects that to last. “We are entering an unprecedented era where the older generation is retiring with vast housing wealth,” says the first in its final paragraph. “That wealth is largely being preserved through retirement and will in due course find its way down through the generations. Public policy making needs to take far more account of these very substantial financial flows and perhaps focus more attention on those who are not likely to be the beneficiaries.”

In other words, we are re-entering the world of the Victorian novel, in which suitable marriages, contested wills and misplaced legacies drive the plot, while the poor – the people without lawyers – press their faces against the window of this vigorous, scheming world and merely invite our sympathy.

It wasn’t supposed to happen. “Come with us, then, towards the next decade,” said Margaret Thatcher, winding up her speech to the Conservative party conference in 1985. “Let us together set our sights on a Britain where three out of four families own their home, where owning shares is as common as having a car, where families have a degree of independence their forefathers could only dream about.”

Anyone under the age of 45 is now much less likely to be a homeowner than people of the same age 25 years ago

Two years later the writer Neal Ascherson wrote a prescient column in the Observer that he recalls as “the most popular column I ever wrote … It was greedily read by the yuppie generation – and then fiercely denounced for being wrong.” Foreseeing that soaring house prices meant that London’s middle-class young would inherit many millions when their parents died, Ascherson predicted an “explosion of liquid wealth that would create instant and colossal inequality”: a society with an upper class rich enough to maintain servants, in a “court city” drained of industry that had reverted to the production of luxurious baubles.

Economists pointed out that the cash raised from property sales wouldn’t be “liquid” – it would be sucked up by the inflated cost of the new houses the inheritors moved into – but from today’s vantage point Ascherson’s futurism does not look so wrong. A new super-rich class with butlers and housemaids has moved in, though mainly from overseas rather than Britain, while owner-occupation has become a mirage for growing numbers of the less well-off.

Homeownership today stands just slightly above the rate when Thatcher made her speech: 64% of all households compared with 61% of all households in 1985, having declined from a peak of 71% in 2003. Anyone under the age of 45 is now much less likely to be a homeowner than people of the same age 25 years ago, while the reverse is true of older age groups.

Private renters account for more than 20% of the housing market; in 1985 the figure was 9%. High rents rule out the kind of savings needed for a deposit on a house – with an average price in London equivalent to more than 16 times the average London salary, and 12 and 13 times the mean income of people in their 20s and 30s in prosperous cities such as Cambridge and Brighton. Meanwhile prices, which might be expected to slump amid the economic uncertainty of Brexit, have instead held reasonably steady because the fall in the value of sterling has made them more attractive to international investors.

As the IFS says, these developments mean that inherited wealth is likely to play a more important – I would say crucial – role “in determining the lifetime economic resources of younger generations, with important implications for inequality and social mobility”. What can grammar schools do – supposing they really are agents of social mobility – against this coming weight of money, which will deepen privilege like a coastal shelf? The metaphor is borrowed from Philip Larkin. “They set you up, your mum and dad. They say they mean to, and they do.” For some of us, This Be the Verse.

From my father’s side the treasures included: a stuffed canary; a tiny stuffed crocodile (a gharial, taken from the Ganges); some crested china bought in seaside resorts; and a canteen of excellent cutlery given as a wedding present in 1899 and never taken from its box. On my grandmother’s death, a display cabinet was bought to accommodate this sudden Victorian infusion into our household, which already had a fine little portrait of Rob Roy inherited from my mother’s father, to be followed much later (after a diversion to an aunt and then a cousin) by a wall-clock and a watercolour of a street in Kirkcaldy that looked very pretty from a distance. I’m sure to have forgotten other items – for example, I’m just now remembering the 78rpm discs of Enrico Caruso and Harry Lauder – but basically that was it.

If there was money, there was very little. No property, you see. Neither side of the family had ever owned a house – and so, in terms of material changes to their children’s lives, their deaths were inconsequential. I, on the other hand, do own a house. More than that, I own a house in London. My death, and that of a million like me, will be very consequential.

According to Steve Webb, policy director of the Royal London mutual insurance company, “a wall of housing wealth [is] set to cascade through the generations in the coming years”.

A study published this week by Royal London estimates that roughly £400bn presently tied up in homes owned by people aged 65 to 85 will be handed down to their children and grandchildren. A typical estate of what the study calls this “wealth mountain” is worth between £400,000 and £500,000, to be shared out between four or five children or adult grandchildren and often to be reinvested in property.

The study is based on a YouGov survey of more than 5,600 people covering three generations: the so-called “grandparents generation” of 65- to 85-year-old homeowners; the “sandwich” generation of parents aged 45 to 64, who have living parents from whom they might expect to inherit; and a “children’s” generation of adults aged 25 to 44 who have owner-occupier parents and grandparents.

Surveys are only surveys: caveat emptor. Nevertheless, the report discovers some intriguing differences between generations. While the youngest group believes that their grandparents should spend freely to enjoy their retirement, the grandparents themselves think it right to hoard their money for their grandchildren. Many don’t wait to die. A third of those aged 75 and over had given sizeable sums of money to their grandchildren, a generation that according to the study’s calculations have received a total of £38bn from both their parents and grandparents – often, especially in London and the south-east, to spend on property. And while grandparents tend to act out of a sense of distant benevolence, parents are responding to the “pressure” exerted by their children’s predicaments. The study’s title picks up this theme: Will harassed “baby boomers” rescue Generation Rent?

Earlier this year, the Institute for Fiscal Studies published research on the growth of inheritance as a phenomenon in British life. It showed how less than 40% of the cohort born in the 1930s have received or expect to receive a bequest, while for those born in the 1970s the figure is 75%. Their benefactors are on average much richer. In 2002-3, the household wealth of people aged 80 and over averaged £160,000; 10 years later, thanks mainly to increases in home ownership and house prices, the average had risen to £230,000.

So far, the impact of inheritance on entrenching or heightening inequality has been fairly small – the average inheritance equals only 3% of the other income its recipient can expect to generate in a lifetime. But neither the Royal London nor the IFS study expects that to last. “We are entering an unprecedented era where the older generation is retiring with vast housing wealth,” says the first in its final paragraph. “That wealth is largely being preserved through retirement and will in due course find its way down through the generations. Public policy making needs to take far more account of these very substantial financial flows and perhaps focus more attention on those who are not likely to be the beneficiaries.”

In other words, we are re-entering the world of the Victorian novel, in which suitable marriages, contested wills and misplaced legacies drive the plot, while the poor – the people without lawyers – press their faces against the window of this vigorous, scheming world and merely invite our sympathy.

It wasn’t supposed to happen. “Come with us, then, towards the next decade,” said Margaret Thatcher, winding up her speech to the Conservative party conference in 1985. “Let us together set our sights on a Britain where three out of four families own their home, where owning shares is as common as having a car, where families have a degree of independence their forefathers could only dream about.”

Anyone under the age of 45 is now much less likely to be a homeowner than people of the same age 25 years ago

Two years later the writer Neal Ascherson wrote a prescient column in the Observer that he recalls as “the most popular column I ever wrote … It was greedily read by the yuppie generation – and then fiercely denounced for being wrong.” Foreseeing that soaring house prices meant that London’s middle-class young would inherit many millions when their parents died, Ascherson predicted an “explosion of liquid wealth that would create instant and colossal inequality”: a society with an upper class rich enough to maintain servants, in a “court city” drained of industry that had reverted to the production of luxurious baubles.

Economists pointed out that the cash raised from property sales wouldn’t be “liquid” – it would be sucked up by the inflated cost of the new houses the inheritors moved into – but from today’s vantage point Ascherson’s futurism does not look so wrong. A new super-rich class with butlers and housemaids has moved in, though mainly from overseas rather than Britain, while owner-occupation has become a mirage for growing numbers of the less well-off.

Homeownership today stands just slightly above the rate when Thatcher made her speech: 64% of all households compared with 61% of all households in 1985, having declined from a peak of 71% in 2003. Anyone under the age of 45 is now much less likely to be a homeowner than people of the same age 25 years ago, while the reverse is true of older age groups.

Private renters account for more than 20% of the housing market; in 1985 the figure was 9%. High rents rule out the kind of savings needed for a deposit on a house – with an average price in London equivalent to more than 16 times the average London salary, and 12 and 13 times the mean income of people in their 20s and 30s in prosperous cities such as Cambridge and Brighton. Meanwhile prices, which might be expected to slump amid the economic uncertainty of Brexit, have instead held reasonably steady because the fall in the value of sterling has made them more attractive to international investors.

As the IFS says, these developments mean that inherited wealth is likely to play a more important – I would say crucial – role “in determining the lifetime economic resources of younger generations, with important implications for inequality and social mobility”. What can grammar schools do – supposing they really are agents of social mobility – against this coming weight of money, which will deepen privilege like a coastal shelf? The metaphor is borrowed from Philip Larkin. “They set you up, your mum and dad. They say they mean to, and they do.” For some of us, This Be the Verse.

No comments:

Post a Comment