Police covered up their attacks on striking miners. And they used the same tactics after the football tragedy.

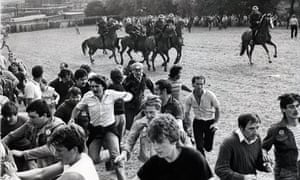

‘For those of us who were there when the ranks of police suddenly opened up and launched a cavalry charge, it felt like civil war.’ Photograph: Photofusion/Rex

Just eight miles separates the patch of ground on the outskirts of Sheffield where Orgreave coking plant once stood from Hillsborough stadium, where 96 people were unlawfully killed on 15 April 1989. To those of us involved in the miners’ strike in south Yorkshire in the 1980s, the so-called “battle of Orgreave” and Britain’s worst football disaster have always been linked.

It was a glorious summer’s day on 18 June 1984. With my son and other mineworkers, I set off for Orgreave to take part in a mass demonstration to try to stop coke being moved from the plant to the steelworks at Scunthorpe.

The miners were in a jovial mood, dressed in T-shirts and plimsolls. To save on petrol most of us travelled four or five to a car. We had been on strike for more than three months, had very little money and relied on the £2 picketing money from the union to pay for petrol. Our destination was to be the scene of one of the bloodiest battle grounds in Britain’s industrial history.

We went to Orgreave to fight to save our industry from what has since been revealed, following the release of cabinet papers in January 2014, as a government plan to kill off the coal mining industry, close 75 pits at a cost of approximately 75,000 jobs, and destroy the National Union of Mineworkers.

The battle of Orgreave was a one-sided contest, as miners suddenly found themselves facing not a police force, but a paramilitary force dressed in riot gear, wielding long truncheons, with strategically placed officers with dogs, and a cavalry charge reminiscent of a medieval battleground.

For those of us who were there when the ranks of police suddenly opened up and launched the charge on horseback, it felt like civil war. Miners had no defence other than to try and outrun the horses. Furthermore, we had to run uphill. Many miners were caught and battered to the ground with truncheons, then outnumbered by police on foot before being roughly handled as they were arrested. Those of us who made it to the top of the hill found refuge in a supermarket or in the nearby mining village.

‘Following the battle, 95 miners were charged with riot, an offence which can carry a life sentence.’ Photograph: Mike Forster/Associated News/Rex

No one died at Orgreave, but it was clearly the intention of the police to create what felt like a life-threatening situation. The police faced no threat from the miners at Orgreave that warranted such a violent response, but it was obvious to those present that the police knew they could act with impunity.

Following the battle, 95 miners were charged with riot, an offence which could carry a life sentence. Gareth Peirce, one of the defending solicitors in the abortive trial that followed, wrote in the Guardian in 1985: “Orgreave … revealed that in this country we now have a standing army available to be deployed against gatherings of civilians whose congregation is disliked by senior police officers. It is answerable to no one; it is trained in tactics which have been released to no one, but which include the deliberate maiming and injuring of innocent persons to disperse them, in complete violation of the law.”

Miners' strike: IPCC considers unredacted Orgreave report

I wasn’t in court when the prosecution of the Orgreave miners was thrown out because the evidence did not stack up. But the trial revealed the way police would collaborate and coordinate evidence in order to get convictions or cover up the truth. In this sense, Orgreave can be seen as a dry run for what happened after the Hillsborough disaster in 1989. Had the South Yorkshire force not been allowed to get away with what they did at Orgreave, perhaps Hillsborough would never have happened.

As the Hillsborough inquest verdicts have shown, we cannot have an unaccountable police force charged with upholding the rule of law but immune to it. We need to know which politicians or officials gave such immunity to the police, if it was given.

Only a full public inquiry into Orgreave will get at the truth, an inquiry to which all documents must be revealed in unredacted form. This inquiry would not just be in the interests of the miners injured on that day, and in the interests of their families. It would be in all our interests, because we all need to understand how a police force came to believe it was a law unto itself. If we don’t, we risk creating the conditions in which another Hillsborough or Orgreave could happen.

In 1985 the miners shouted from the rooftops, but we weren’t heard. Ignored by the media, many gave up. What happened at Orgreave was not a human tragedy on the same scale as Hillsborough. But now, thanks to the tremendous campaign by the Hillsborough families who lost loved ones, and who refused to give up their fight for justice, we have the chance to discover the truth about what happened at Orgreave too.