'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label battle. Show all posts

Showing posts with label battle. Show all posts

Friday, 18 November 2022

Monday, 28 June 2021

Monday, 7 June 2021

Israel - A PSYCHOTIC BREAK FROM REALITY?

Nadeem F. Paracha in The Dawn

Illustration by Abro

Illustration by Abro

The New York Times, in its May 28, 2021 issue, published a collage of photographs of 67 children under the age of 18 who had been killed in the recent Israeli air attacks on Gaza and by Hamas on Tel Aviv. Two of the children had been killed in Israel by shrapnel from rockets fired by Hamas. It is only natural for any normal human being to ask, how can one kill children?

Similar collages appear every year on social media of the over 140 students who were mercilessly gunned down in 2014 at the Army Public School in Peshawar. The killings were carried out by the militant organisation the Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). Most Pakistanis could not comprehend how even a militant group could massacre school children. But there were also those who questioned why the children were targeted.

The ‘why’ in this context is apparently understood at an individual level when certain individuals sexually assault children and often kill them. Psychologists are of the view that such individuals — paedophiles — are mostly men who have either suffered sexual abuse as children themselves, or are overwhelmed by certain psychological disorders that lead to developing questionable sexual urges.

In the 1982 anthology Behaviour Modification and Therapy, W.L. Marshall writes that paedophilia co-occurs with low self-esteem, depression and other personality disorders. These can be because of the individual’s own experiences as a sexually abused child or, according to the 2008 issue of the Journal of Psychiatric Research, paedophiles may have different brain structures which cause personality disorders and social failings, leading them to develop deviant sexual behaviours.

But why do some paedophiles end up murdering their young victims? This may be to eliminate the possibility of their victims naming them after the assault, or the young victims die because their bodies are still not developed to accommodate even the most basic sexual acts. According to a 1992 study by the Behavioural Science Unit of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in the US, some paedophiles can also develop sadism as a disorder, which eventually compels them to derive pleasure by inflicting pain and killing their young victims.

Why did Israel kill so many children in its bombardment of Gaza? Could it be that it has something in common with apocalyptic terror groups, for whom killing children is simply collateral damage in a divinely ordained cosmic battle?

Now the question is, are modern-day governments, militaries and terrorist groups that knowingly massacre children, also driven by the same sadistic impulses? Do they extract pleasure from slaughtering children? It is possible that military massacres that include the death of a large number of children are acts of frustration and blind rage by soldiers made to fight wars that are being lost.

The March 1968 ‘My Lai massacre’, carried out by US soldiers in Vietnam, is a case in point. Over 500 people, including children, were killed in that incident. Even women who were carrying babies in their arms, were shot dead. Just a month earlier, communist insurgents had attacked South Vietnamese cities held by US forces. The insurgents were driven out, but they were able to kill a large number of US soldiers. Also, the war in Vietnam had become unpopular in the US. Soldiers were dismayed by stories about returning US marines being insulted, ridiculed and rejected at home for fighting an unjust and immoral war.

Indeed, desperate armies have been known to kill the most vulnerable members of the enemy, such as children, in an attempt to psychologically compensate for their inability to fight effectively against their adult opponents. But what about the Israeli armed forces? What frustrations are they facing? They have successfully neutralised anti-Israel militancy. And the Palestinians and their supporters are no match against Israel’s war machine. So why did Israeli forces knowingly kill so many Palestinian children in Gaza?

A May 21, 2021 report published on the Al-Jazeera website quotes a Palestinian lawyer, Youssef al-Zayed, as saying that Israeli forces were ‘intentionally targeting minors to terrorise an entire generation from speaking out.’ Ever since 1987, Palestinian children have been in the forefront of protests against armed Israeli forces. The children are often armed with nothing more than stones.

What Israel is doing against its Arab population, and in the Palestinian Territories that are still largely under its control, can be called ‘democide.’ Coined by the American political scientist Rudolph Rummel, the word democide means acts of genocide by a government/ state against a segment of its own population. Such acts constitute the systematic elimination of people belonging to minority religious or ethnic communities. According to Rummel, this is done because the persecuted communities are perceived as being ‘future threats’ by the dominant community.

So, do terrorist outfits such as TTP, Islamic State and Boko Haram, for example, who are known to also target children, do so because they see children as future threats?

In a 2018 essay for the Journal of Strategic Studies, the forensic psychologist Karl Umbrasas writes that terror outfits who kill indiscriminately can be categorised as ‘apocalyptic groups.’ According to Umbrasas, such groups operate like ‘apocalyptic cults’ and are not restrained by the socio-political and moral restraints that compel non-apocalyptic militant outfits to only focus on attacking armed, non-civilian targets. Umbrasas writes that apocalyptic terror groups justify acts of indiscriminate destruction through their often distorted and violent interpretations of sacred texts.

Such groups are thus completely unrepentant about targeting even children. To them the children, too, are part of the problem that they are going to resolve through a ‘cosmic war.’ The idea of a cosmic war constitutes an imagined battle between metaphysical forces — good and evil — that is behind many cases of religion-related violence.

Interestingly, this was also how the Afghan civil war of the 1980s between Islamist groups and Soviet troops was framed by the US, Saudi Arabia and Pakistan. The cosmic bit evaporated for the three states after the departure of Soviet troops, but the idea of the cosmic conflict remained in the minds of various terror groups in the region.

The moral codes of apocalyptic terror groups transcend those of the modern world. So, for example, on May 9 this year, when a terrorist group targeted a girls’ school in Afghanistan, killing 80, it is likely it saw girl students as part of the evil side in the divinely ordained cosmic war that the group imagines itself to be fighting.

This indeed is the result of a psychotic break from reality. But it is a reality that apocalyptic terror outfits do not accept. To them, this reality is a social construct. There is no value of the physical human body in such misshaped metaphysical ideas. Therefore, even if a cosmic war requires the killing of children, it is just the destruction of bodies, no matter what their size.

Illustration by Abro

Illustration by AbroThe New York Times, in its May 28, 2021 issue, published a collage of photographs of 67 children under the age of 18 who had been killed in the recent Israeli air attacks on Gaza and by Hamas on Tel Aviv. Two of the children had been killed in Israel by shrapnel from rockets fired by Hamas. It is only natural for any normal human being to ask, how can one kill children?

Similar collages appear every year on social media of the over 140 students who were mercilessly gunned down in 2014 at the Army Public School in Peshawar. The killings were carried out by the militant organisation the Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). Most Pakistanis could not comprehend how even a militant group could massacre school children. But there were also those who questioned why the children were targeted.

The ‘why’ in this context is apparently understood at an individual level when certain individuals sexually assault children and often kill them. Psychologists are of the view that such individuals — paedophiles — are mostly men who have either suffered sexual abuse as children themselves, or are overwhelmed by certain psychological disorders that lead to developing questionable sexual urges.

In the 1982 anthology Behaviour Modification and Therapy, W.L. Marshall writes that paedophilia co-occurs with low self-esteem, depression and other personality disorders. These can be because of the individual’s own experiences as a sexually abused child or, according to the 2008 issue of the Journal of Psychiatric Research, paedophiles may have different brain structures which cause personality disorders and social failings, leading them to develop deviant sexual behaviours.

But why do some paedophiles end up murdering their young victims? This may be to eliminate the possibility of their victims naming them after the assault, or the young victims die because their bodies are still not developed to accommodate even the most basic sexual acts. According to a 1992 study by the Behavioural Science Unit of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in the US, some paedophiles can also develop sadism as a disorder, which eventually compels them to derive pleasure by inflicting pain and killing their young victims.

Why did Israel kill so many children in its bombardment of Gaza? Could it be that it has something in common with apocalyptic terror groups, for whom killing children is simply collateral damage in a divinely ordained cosmic battle?

Now the question is, are modern-day governments, militaries and terrorist groups that knowingly massacre children, also driven by the same sadistic impulses? Do they extract pleasure from slaughtering children? It is possible that military massacres that include the death of a large number of children are acts of frustration and blind rage by soldiers made to fight wars that are being lost.

The March 1968 ‘My Lai massacre’, carried out by US soldiers in Vietnam, is a case in point. Over 500 people, including children, were killed in that incident. Even women who were carrying babies in their arms, were shot dead. Just a month earlier, communist insurgents had attacked South Vietnamese cities held by US forces. The insurgents were driven out, but they were able to kill a large number of US soldiers. Also, the war in Vietnam had become unpopular in the US. Soldiers were dismayed by stories about returning US marines being insulted, ridiculed and rejected at home for fighting an unjust and immoral war.

Indeed, desperate armies have been known to kill the most vulnerable members of the enemy, such as children, in an attempt to psychologically compensate for their inability to fight effectively against their adult opponents. But what about the Israeli armed forces? What frustrations are they facing? They have successfully neutralised anti-Israel militancy. And the Palestinians and their supporters are no match against Israel’s war machine. So why did Israeli forces knowingly kill so many Palestinian children in Gaza?

A May 21, 2021 report published on the Al-Jazeera website quotes a Palestinian lawyer, Youssef al-Zayed, as saying that Israeli forces were ‘intentionally targeting minors to terrorise an entire generation from speaking out.’ Ever since 1987, Palestinian children have been in the forefront of protests against armed Israeli forces. The children are often armed with nothing more than stones.

What Israel is doing against its Arab population, and in the Palestinian Territories that are still largely under its control, can be called ‘democide.’ Coined by the American political scientist Rudolph Rummel, the word democide means acts of genocide by a government/ state against a segment of its own population. Such acts constitute the systematic elimination of people belonging to minority religious or ethnic communities. According to Rummel, this is done because the persecuted communities are perceived as being ‘future threats’ by the dominant community.

So, do terrorist outfits such as TTP, Islamic State and Boko Haram, for example, who are known to also target children, do so because they see children as future threats?

In a 2018 essay for the Journal of Strategic Studies, the forensic psychologist Karl Umbrasas writes that terror outfits who kill indiscriminately can be categorised as ‘apocalyptic groups.’ According to Umbrasas, such groups operate like ‘apocalyptic cults’ and are not restrained by the socio-political and moral restraints that compel non-apocalyptic militant outfits to only focus on attacking armed, non-civilian targets. Umbrasas writes that apocalyptic terror groups justify acts of indiscriminate destruction through their often distorted and violent interpretations of sacred texts.

Such groups are thus completely unrepentant about targeting even children. To them the children, too, are part of the problem that they are going to resolve through a ‘cosmic war.’ The idea of a cosmic war constitutes an imagined battle between metaphysical forces — good and evil — that is behind many cases of religion-related violence.

Interestingly, this was also how the Afghan civil war of the 1980s between Islamist groups and Soviet troops was framed by the US, Saudi Arabia and Pakistan. The cosmic bit evaporated for the three states after the departure of Soviet troops, but the idea of the cosmic conflict remained in the minds of various terror groups in the region.

The moral codes of apocalyptic terror groups transcend those of the modern world. So, for example, on May 9 this year, when a terrorist group targeted a girls’ school in Afghanistan, killing 80, it is likely it saw girl students as part of the evil side in the divinely ordained cosmic war that the group imagines itself to be fighting.

This indeed is the result of a psychotic break from reality. But it is a reality that apocalyptic terror outfits do not accept. To them, this reality is a social construct. There is no value of the physical human body in such misshaped metaphysical ideas. Therefore, even if a cosmic war requires the killing of children, it is just the destruction of bodies, no matter what their size.

Friday, 6 May 2016

The lies binding Hillsborough to the battle of Orgreave

Ken Capstick in The Guardian

Police covered up their attacks on striking miners. And they used the same tactics after the football tragedy.

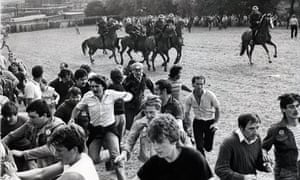

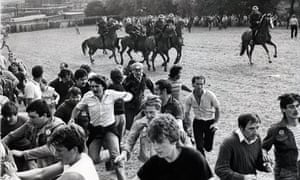

‘For those of us who were there when the ranks of police suddenly opened up and launched a cavalry charge, it felt like civil war.’ Photograph: Photofusion/Rex

Just eight miles separates the patch of ground on the outskirts of Sheffield where Orgreave coking plant once stood from Hillsborough stadium, where 96 people were unlawfully killed on 15 April 1989. To those of us involved in the miners’ strike in south Yorkshire in the 1980s, the so-called “battle of Orgreave” and Britain’s worst football disaster have always been linked.

It was a glorious summer’s day on 18 June 1984. With my son and other mineworkers, I set off for Orgreave to take part in a mass demonstration to try to stop coke being moved from the plant to the steelworks at Scunthorpe.

The miners were in a jovial mood, dressed in T-shirts and plimsolls. To save on petrol most of us travelled four or five to a car. We had been on strike for more than three months, had very little money and relied on the £2 picketing money from the union to pay for petrol. Our destination was to be the scene of one of the bloodiest battle grounds in Britain’s industrial history.

We went to Orgreave to fight to save our industry from what has since been revealed, following the release of cabinet papers in January 2014, as a government plan to kill off the coal mining industry, close 75 pits at a cost of approximately 75,000 jobs, and destroy the National Union of Mineworkers.

The battle of Orgreave was a one-sided contest, as miners suddenly found themselves facing not a police force, but a paramilitary force dressed in riot gear, wielding long truncheons, with strategically placed officers with dogs, and a cavalry charge reminiscent of a medieval battleground.

For those of us who were there when the ranks of police suddenly opened up and launched the charge on horseback, it felt like civil war. Miners had no defence other than to try and outrun the horses. Furthermore, we had to run uphill. Many miners were caught and battered to the ground with truncheons, then outnumbered by police on foot before being roughly handled as they were arrested. Those of us who made it to the top of the hill found refuge in a supermarket or in the nearby mining village.

‘Following the battle, 95 miners were charged with riot, an offence which can carry a life sentence.’ Photograph: Mike Forster/Associated News/Rex

No one died at Orgreave, but it was clearly the intention of the police to create what felt like a life-threatening situation. The police faced no threat from the miners at Orgreave that warranted such a violent response, but it was obvious to those present that the police knew they could act with impunity.

Following the battle, 95 miners were charged with riot, an offence which could carry a life sentence. Gareth Peirce, one of the defending solicitors in the abortive trial that followed, wrote in the Guardian in 1985: “Orgreave … revealed that in this country we now have a standing army available to be deployed against gatherings of civilians whose congregation is disliked by senior police officers. It is answerable to no one; it is trained in tactics which have been released to no one, but which include the deliberate maiming and injuring of innocent persons to disperse them, in complete violation of the law.”

Miners' strike: IPCC considers unredacted Orgreave report

I wasn’t in court when the prosecution of the Orgreave miners was thrown out because the evidence did not stack up. But the trial revealed the way police would collaborate and coordinate evidence in order to get convictions or cover up the truth. In this sense, Orgreave can be seen as a dry run for what happened after the Hillsborough disaster in 1989. Had the South Yorkshire force not been allowed to get away with what they did at Orgreave, perhaps Hillsborough would never have happened.

As the Hillsborough inquest verdicts have shown, we cannot have an unaccountable police force charged with upholding the rule of law but immune to it. We need to know which politicians or officials gave such immunity to the police, if it was given.

Only a full public inquiry into Orgreave will get at the truth, an inquiry to which all documents must be revealed in unredacted form. This inquiry would not just be in the interests of the miners injured on that day, and in the interests of their families. It would be in all our interests, because we all need to understand how a police force came to believe it was a law unto itself. If we don’t, we risk creating the conditions in which another Hillsborough or Orgreave could happen.

In 1985 the miners shouted from the rooftops, but we weren’t heard. Ignored by the media, many gave up. What happened at Orgreave was not a human tragedy on the same scale as Hillsborough. But now, thanks to the tremendous campaign by the Hillsborough families who lost loved ones, and who refused to give up their fight for justice, we have the chance to discover the truth about what happened at Orgreave too.

Police covered up their attacks on striking miners. And they used the same tactics after the football tragedy.

‘For those of us who were there when the ranks of police suddenly opened up and launched a cavalry charge, it felt like civil war.’ Photograph: Photofusion/Rex

Just eight miles separates the patch of ground on the outskirts of Sheffield where Orgreave coking plant once stood from Hillsborough stadium, where 96 people were unlawfully killed on 15 April 1989. To those of us involved in the miners’ strike in south Yorkshire in the 1980s, the so-called “battle of Orgreave” and Britain’s worst football disaster have always been linked.

It was a glorious summer’s day on 18 June 1984. With my son and other mineworkers, I set off for Orgreave to take part in a mass demonstration to try to stop coke being moved from the plant to the steelworks at Scunthorpe.

The miners were in a jovial mood, dressed in T-shirts and plimsolls. To save on petrol most of us travelled four or five to a car. We had been on strike for more than three months, had very little money and relied on the £2 picketing money from the union to pay for petrol. Our destination was to be the scene of one of the bloodiest battle grounds in Britain’s industrial history.

We went to Orgreave to fight to save our industry from what has since been revealed, following the release of cabinet papers in January 2014, as a government plan to kill off the coal mining industry, close 75 pits at a cost of approximately 75,000 jobs, and destroy the National Union of Mineworkers.

The battle of Orgreave was a one-sided contest, as miners suddenly found themselves facing not a police force, but a paramilitary force dressed in riot gear, wielding long truncheons, with strategically placed officers with dogs, and a cavalry charge reminiscent of a medieval battleground.

For those of us who were there when the ranks of police suddenly opened up and launched the charge on horseback, it felt like civil war. Miners had no defence other than to try and outrun the horses. Furthermore, we had to run uphill. Many miners were caught and battered to the ground with truncheons, then outnumbered by police on foot before being roughly handled as they were arrested. Those of us who made it to the top of the hill found refuge in a supermarket or in the nearby mining village.

‘Following the battle, 95 miners were charged with riot, an offence which can carry a life sentence.’ Photograph: Mike Forster/Associated News/Rex

No one died at Orgreave, but it was clearly the intention of the police to create what felt like a life-threatening situation. The police faced no threat from the miners at Orgreave that warranted such a violent response, but it was obvious to those present that the police knew they could act with impunity.

Following the battle, 95 miners were charged with riot, an offence which could carry a life sentence. Gareth Peirce, one of the defending solicitors in the abortive trial that followed, wrote in the Guardian in 1985: “Orgreave … revealed that in this country we now have a standing army available to be deployed against gatherings of civilians whose congregation is disliked by senior police officers. It is answerable to no one; it is trained in tactics which have been released to no one, but which include the deliberate maiming and injuring of innocent persons to disperse them, in complete violation of the law.”

Miners' strike: IPCC considers unredacted Orgreave report

I wasn’t in court when the prosecution of the Orgreave miners was thrown out because the evidence did not stack up. But the trial revealed the way police would collaborate and coordinate evidence in order to get convictions or cover up the truth. In this sense, Orgreave can be seen as a dry run for what happened after the Hillsborough disaster in 1989. Had the South Yorkshire force not been allowed to get away with what they did at Orgreave, perhaps Hillsborough would never have happened.

As the Hillsborough inquest verdicts have shown, we cannot have an unaccountable police force charged with upholding the rule of law but immune to it. We need to know which politicians or officials gave such immunity to the police, if it was given.

Only a full public inquiry into Orgreave will get at the truth, an inquiry to which all documents must be revealed in unredacted form. This inquiry would not just be in the interests of the miners injured on that day, and in the interests of their families. It would be in all our interests, because we all need to understand how a police force came to believe it was a law unto itself. If we don’t, we risk creating the conditions in which another Hillsborough or Orgreave could happen.

In 1985 the miners shouted from the rooftops, but we weren’t heard. Ignored by the media, many gave up. What happened at Orgreave was not a human tragedy on the same scale as Hillsborough. But now, thanks to the tremendous campaign by the Hillsborough families who lost loved ones, and who refused to give up their fight for justice, we have the chance to discover the truth about what happened at Orgreave too.

Sunday, 12 May 2013

History is where the great battles of public life are now being fought

From curriculum rows to Niall Ferguson's remarks on Keynes, our past is the fuel for debate about the future

Historian Niall Ferguson: 'Part of a worryingly conservative consensus when it comes to framing our national past.' Photograph: Channel 4

The bullish Harvard historian Niall Ferguson cut an unfamiliar, almost meek figure last week. As reports of his ugly suggestion that John Maynard Keynes's homosexuality had made the great economist indifferent to the prospects of future generations surged across the blogosphere, Ferguson wisely went for a mea culpa.

So, in a cringeing piece for Harvard University's student magazine, the professor, who usually so enjoys confronting political correctness, denied he was homophobic or, indeed, racist and antisemitic for good measure.

Of course, Ferguson is none of those things. He is a brilliant financial historian, albeit with a debilitating weakness for the bon mot. But Ferguson is also part of a worryingly conservative consensus when it comes to framing our national past.

For whether it is David Starkey on Question Time, in a frenzy of misogyny and self-righteousness, denouncing Harriet Harman and Shirley Williams for being well-connected, metropolitan members of the Labour movement, or the reactionary Dominic Sandbrook using the Daily Mail to condemn with Orwellian menace any critical interpretation of Mrs Thatcher's legacy, the historical right has Britain in its grip.

And it has so at a crucial time. The rise of Ukip, combined with David Cameron's political weakness, means that, even in the absence of an official "in or out" referendum on our place in Europe, it looks like we will be debating Britain's place in the world for some years to come. And we will do against the backdrop of Michael Gove's proposed new history curriculum which, for some of its virtues, threatens to make us less, not more, confident about our internationalist standing.

For as Ferguson has discovered to his cost, history enjoys a uniquely controversial place within British public life. "There is no part of the national curriculum so likely to prove an ideological battleground for contending armies as history," complained an embattled Michael Gove in a speech last week. "There may, for all I know, be rival Whig and Marxist schools fighting a war of interpretation in chemistry or food technology but their partisans don't tend to command much column space in the broadsheets."

Even if academic historians might not like it, politicians are right to involve themselves in the curriculum debate. The importance of history in the shaping of citizenship, developing national identity and exploring the ties that bind in our increasingly disparate, multicultural society demands a democratic input. The problem is that too many of the progressive partisans we need in this struggle are missing from the field.

How different it all was 50 years ago this summer when EP Thompson published The Making of the English Working Class , his seminal account of British social history during the Industrial Revolution. "I am seeking to rescue the poor stockinger, the Luddite cropper, the 'obsolete' hand loom weaver, the 'utopian' artist ... from the condescension of posterity," he wrote.

He did so in magisterial style, providing an intimate chronicle of the brutality inflicted on the English labouring classes as Britain rose to be the workshop of the world. Thompson focused on the human stories – the Staffordshire potters, the Manchester Chartists – to build an account of an emergent, proletarian identity. It was social history as a political project, seeking to lay out all the tensions and conflict that really lie behind our island story.

As his fellow Marxist Eric Hobsbawm put it, social history was "the organisational and ideological history of the labour movement". Uncovering the lost lives and experiences of the miner and mill worker was a way of contesting power in the present. And in the wake of Thompson and Hobsbawm's histories – as well as the work of Raphael Samuel, Asa Briggs and Christopher Hill – popular interpretations of the past shifted.

In theatre, television, radio and museums, a far more vernacular and democratic account of the British past started to flourish. If, today, we are as much concerned about downstairs as upstairs, about Downton Abbey's John Bates as much as the Earl of Grantham, it is thanks to this tradition of progressive social history.

It even influenced high politics. In the flickering gloom of the 1970s' three-day week, Tony Benn retreated to the House of Commons tearoom to read radical accounts of the English civil war. "I had no idea that the Levellers had called for universal manhood suffrage, equality between the sexes and the sovereignty of the people," he confided to his diary. Benn, the semi-detached Labour cabinet minister, felt able to place himself seamlessly within this historical lineage – lamenting how "the Levellers lost and Cromwell won, and Harold Wilson or Denis Healey is the Cromwell of our day, not me".

But despite recent histories by the likes of Emma Griffin on industrialising England orEdward Vallance on radical Britain, the place of the progressive past in contemporary debate has now been abandoned. So much of the left has mired itself in the discursive dead ends of postmodernism or decided to focus its efforts abroad on the crimes of our colonial past. In their absence, we are left with Starkey and Ferguson – and BBC2 about to air yet another series on the history of the Tudor court. How much information about Anne Boleyn can modern Britain really cope with?

This narrowing of the past comes against the backdrop of ever more state school pupils being denied appropriate time for history. While studying the past is protected in prep schools, GCSE exam entries show it is under ever greater pressure in more deprived parts of the country.

Then there is the question of what students will actually be learning. Michael Gove's proposed new syllabus has rightly been criticised by historian David Cannadine and others as too prescriptive, dismissive of age-specific learning and Anglocentric. While the education secretary's foregrounding of British history is right, experts are adamant this parochial path is not the way to do it. Indeed, cynics might wonder whether Gove – the arch Eurosceptic – is already marshalling his young troops for a referendum no vote.

For whether it is the long story of Britain's place in Europe, the 1930s failings of austerity economics, the cultural history of same-sex marriage or the legacy of Thatcherism, the progressive voice in historical debate needs some rocket boosters. Niall Ferguson's crime was not just foolishly to equate Keynes's homosexuality with selfishness. Rather, it was to deny the relevance of Keynes's entire political economy – and, in the process, help to forge a governing consensus that is proving disastrous for British living standards.

That is what we need an apology for.

Wednesday, 16 May 2012

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)