'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Thursday, 5 October 2023

Saturday, 22 July 2023

A Level Economics 73: Introduction to Aggregate Supply

The Aggregate Supply (AS) Function:

The Aggregate Supply (AS) function represents the total output of goods and services that all firms in an economy are willing and able to produce at different price levels. It is crucial to distinguish between the short run and the long run in the context of the AS function. In the short run, some input prices may be fixed or sticky, while in the long run, all input prices are flexible and can adjust fully.

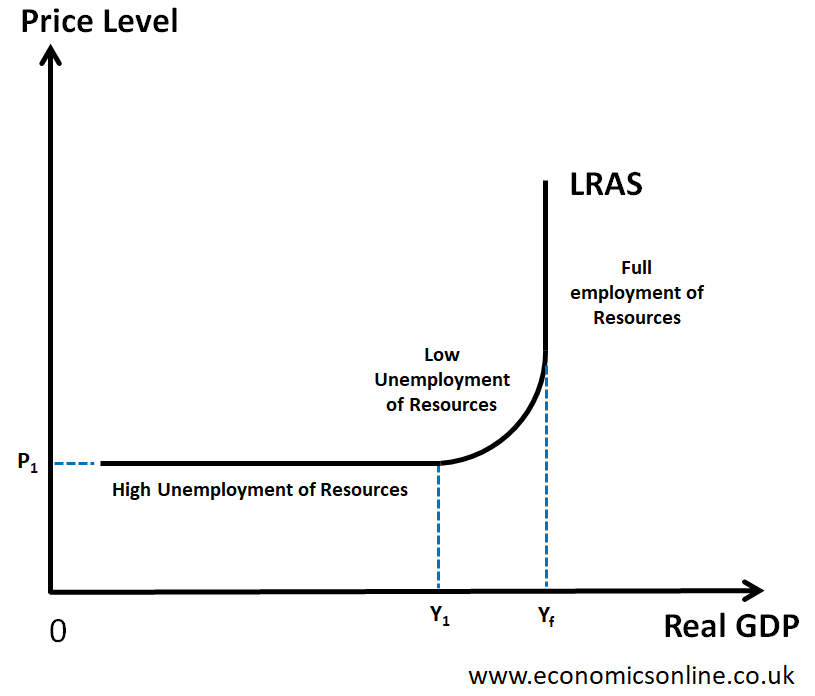

Shape of the Keynesian Long Run Aggregate Supply (LRAS) Curve:

The Keynesian Long Run Aggregate Supply (LRAS) curve is a horizontal line that indicates the level of aggregate supply in the long run when the economy is not operating at full employment. Unlike the classical or neoclassical LRAS curve, which is vertical at the full employment level of output, the Keynesian LRAS curve is horizontal or flat. This suggests that, in the long run, the economy can have persistent unemployment or output gaps.

Factors Resulting in a Shift in LRAS:

Changes in Quantity, Quality, and Efficiency of Factors of Production: An increase in the quantity of factors of production, such as labor and capital, can lead to an outward shift of the LRAS curve. Similarly, improvements in the quality and efficiency of these factors can also result in a higher LRAS. For example, if the workforce becomes more skilled and educated or if technological advancements enhance productivity, the LRAS curve can shift to the right.

Changes in the State of Technology: Technological advancements can significantly impact LRAS. Improvements in technology lead to increased productivity and efficiency, allowing firms to produce more output at the same cost, leading to an outward shift of the LRAS curve.

Changes in Factor Market Flexibility: If factor markets become more flexible, for example, through labor market reforms or reduced barriers to entry for new businesses, this can enhance resource allocation efficiency and lead to a higher LRAS.

LRAS Vertical at Full Employment:

It is essential for learners to understand that the Keynesian LRAS curve is different from the classical or neoclassical LRAS curve. The Keynesian LRAS curve is horizontal, indicating that the economy can have deviations from full employment in the long run. This means that in the long run, the economy's productive capacity is not fully utilized, and there is the possibility of cyclical unemployment.

Using Policy Instruments to Shift LRAS:

Changes in policy instruments can be implemented to bring about shifts in the LRAS curve and improve the economy's productive capacity:

Investment in Education and Training: By investing in education and skill development, the quality and efficiency of the labor force can improve, leading to an outward shift of LRAS.

Infrastructure Development: Building better infrastructure can enhance the productivity of businesses, reducing costs and increasing potential output.

Research and Development (R&D) Support: Encouraging R&D activities can foster technological advancements, contributing to a higher LRAS.

Labor Market Reforms: Implementing policies that increase labor market flexibility, such as reducing minimum wage rigidity or easing labor market regulations, can boost LRAS.

Tax Incentives for Investment: Providing tax incentives to businesses for capital investment can encourage technological progress and lead to an increase in LRAS.

By implementing appropriate policy measures, governments can positively impact the LRAS curve and promote economic growth and full employment in the long run. It is essential for learners to understand these policy instruments and their potential effects on the economy's productive capacity.

Wednesday, 7 June 2023

Governments can borrow more than was once believed

From The Economist

If people know one thing about the thinking of John Maynard Keynes, who more or less founded macroeconomics, it is that he was in favour of governments borrowing lots of money, at least under some circumstances. The “New Keynesian” orthodoxy that evolved from his work in the second half of the 20th century was much less liberal in this regard. It put less faith in borrowing’s purported benefits, and had greater concerns about its dangers.

The 2010s saw the pendulum swinging back. In large part because they feel bereft of other options, many governments have borrowed heavily—and as yet they have paid no dreadful price. Can this go on?

Keynes’s ideas about borrowing reflected his view of recessions—and in particular, the Depression of the 1930s, during which he wrote “The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money”—as vicious circles. Recessions come about when the economy is hit by a sudden rise in the desire to save money; such desires lead to lower spending, which leads to more unemployment, which leads to yet less spending, and so on. If the government borrows enough to offset lower private spending with increased spending of its own the circle can be broken—or stopped from getting going.

Most early Keynesians assumed that the deficits caused by borrowing to stimulate the economy would be temporary; after borrowing more than they raised in taxes in order to provide a fiscal stimulus, governments would be able to raise more in taxes, and thus pay off their debts, in the good times that followed. Some, though, suspected that the structure of the advanced economies of the 1930s might mean they were low on demand even in the good times, and that a permanent deficit might be necessary to keep the economy going at a rate that minimised unemployment.

Debates about the proper role of fiscal stimulus became less urgent in the decades after the second world war, as robust economic growth eased worries that demobilisation might bring a return of Depression-like conditions. Faith in Keynesian orthodoxy was further shaken by the economic developments of the 1970s and 1980s. Some economists began to argue that the public would eventually adjust to stimulus measures in ways that weakened their impact. Robert Barro, a leading proponent of this “rational expectations” approach, argued that a fiscal stimulus paid for by borrowing would see households spend less and save more, because they would know that tax rises were coming. This decreased private spending would then offset the increased public spending.

Linked to, but broader than, such academic questions was the fact that, by the 1970s, the ways in which Keynesian governments had been running their economies seemed to have failed. A trifecta of slowing growth, soaring inflation and high unemployment brought the idea of governments being able to avoid recessions through stimulus into disrepute.

The new orthodoxy was that governments should instead rely on monetary policy. When the economy slowed, monetary policy would loosen, making it cheaper to borrow, thus encouraging people to spend. Government borrowing, for its part, should be kept on a short leash. If governments pushed up their debt-to-gdp ratio, markets would become unwilling to lend to them, forcing up interest rates willy-nilly. The usefulness of monetary policy demanded a sober approach to fiscal policy.

The 2000s, however, saw a problem with this approach beginning to become plain. From the 1980s, interest rates had been in a long, steady decline. By the 2000s they had reached historical lows. Low rates made it harder for central banks to stimulate economies by cutting them further: there was not room to do so. The global financial crisis pushed rates around the world to near zero.

Governments experimented with more radical monetary policy, such as the form of money printing known as “quantitative easing”. Their economies continued to underperform. There seemed to be room for new thinking, and a revamped Keynesianism sought to provide it. In 2012 Larry Summers, a former American treasury secretary, and Brad DeLong, an economist, suggested a large Keynesian stimulus based on borrowing. Thanks to low interest rates, the gains it would provide by boosting the growth rate of gdp might outstrip the cost of financing the debt taken on.

In the following year Mr Summers followed some 1930s Keynesians, notably Alvin Hansen, in suggesting that borrowing in order to stimulate might be needed not just as an occasional pick-me-up, but as a permanent part of the economy. Hansen had argued that an ageing population and a low rate of technological innovation produced a long-term lack of demand which he called “secular stagnation”. Mr Summers took an updated but similar view. Part of his backing for this idea was that the long-term decline of interest rates showed a persistent lack of demand.

Way down we go

Sceptics insisted that such borrowing would drive interest rates up. But as the years went by and interest rates remained stubbornly low, the notion of borrowing for fiscal stimulus started to seem more tenable, even attractive. Very low interest rates mean that economies can grow faster than debt repayments do. Negative interest rates, which have been seen in some countries over recent years, mean that the amount to repay will actually be less than the amount borrowed.

Adherents of “Modern Monetary Theory” (mmt) went further than this, arguing that governments should borrow as much as was needed to achieve full employment while central banks focused simply on keeping interest rates low—a course of action which orthodox economics would expect to promptly drive up inflation. Currently mmt remains on the fringes of academic economics. But it has been embraced by some left-wing politicians; Senator Bernie Sanders, the candidate beaten by Joe Biden for the Democratic nomination, counted an mmt enthusiast, Stephanie Kelton of Stony Brook University, among his chief advisers.

The shift in mainstream thinking on debt helps explain why the huge amounts of government borrowing with which the world has responded to the pandemic has not worried economists. But now that governments have, if only for want of an alternative, become more willing to take on debt, what should be their limit? For an empirical answer, it is tempting to consider Japan, where the ratio of net public debt to gdp stood at 154% prior to the pandemic.

If Japan can continue to borrow with that level of debt, it might seem that countries with lower levels should also be fine. But this ignores the fact that if interest rates stagger back from the floor, burdens a lot smaller than Japan’s might become perilously unstable. There is no immediate account for why this might be likely. But that does not mean it will not happen. And governments need to remember that debt taken on at one interest rate may, if market sentiment changes, need to be rolled over at a much higher one in times to come.

Given this background risk, governments ideally ought to make sure that new borrowing is doing things that will provide a lasting good, greater than the final cost of the borrowing. If money is very cheap and likely to remain so, this will look like a fairly low bar. But there are opportunity costs to consider. If private borrowing has a high return and public borrowing crowds it out, then the public borrowing either needs to show a similarly high return or it needs to be cut back.

At the moment private returns remain well above the cost of new borrowing in most places: in America, for instance, the earnings of corporations are generally high relative to the replacement cost of their capital. This makes it conceivable that resources used by the government would generate a greater level of welfare if they were instead mobilised by private firms.

But it does not currently look as though they would be. Despite the seemingly high returns to new capital, private investment in America is quite low. This suggests either that there are other obstacles to new investment, or that the high returns on investment reflect an insufficient level of competition rather than highly productive companies.

Both possibilities call for government remedy: either action aimed at identifying and dismantling the obstacles to investment, or at increasing competition. And until such actions produce greater investment or lower returns, the case for government borrowing remains quite strong. This is even more the case for public investments which might in themselves encourage the private sector to match them—“crowding in”, as opposed to crowding out. Investment in a much better electricity grid, for example, could increase investment in zero-carbon generation.

In the long run, the way to avoid having to borrow to the hilt is to implement structural changes which will revive what does seem to be chronically weak demand. Unfortunately, there is no consensus over why demand is weak. Is technological progress, outside the realm of computers and communications, not what it was? Is inequality putting money into the hands of the rich, who are less likely to spend their next dollar, rather than the poor, who are more likely? Are volatile financial markets encouraging precautionary saving both by firms and governments? Is the ageing of the population at the root of it all?

Making people younger is not a viable policy option. But the volatility of markets might be addressed by regulation, and a lack of competition by antitrust actions. If inequality is at the root, redistribution (or its jargony cousin, predistribution) could perk up demand. Dealing with the structural problems constraining demand would probably push up interest rates, creating difficulties for those governments which have already accumulated large debt piles. But stronger underlying growth would subsequently reduce the need for further government borrowing, raise gdp and boost tax revenues. In principle that would make it easier for governments in such situations to pay down their increased debt.

The new consensus that government borrowing and spending is indeed an important part of stabilising an economy, and that interest rates are generally low enough to allow governments to manage this task at minimal cost, represents progress. Government borrowing is badly needed to deal with many of the world’s current woes. But this consensus should ideally include two additional planks: that the quality of deficit-spending still matters, and that governments should prepare for the possibility of an eventual change in the global interest-rate environment—much as 2020 has shown that you should prepare for any low-probability disaster.

Thursday, 8 April 2021

The Covid crisis is doing what the 2008 crash didn’t: ending the old economic orthodoxies

A wealth tax to help pay for the cost of fighting the pandemic. An international agreement to prevent a race to the bottom on corporate tax. An insistence that recovery from the second severe crisis in just over a decade should be green and inclusive. A conviction that governments should spend whatever it takes to fend off the threat of mass unemployment, paying no heed to the size of budget deficit.

There’s nothing startlingly new about any of these ideas, which have been knocking around for years, if not decades. What is different is that these are no longer just proposals put forward by progressive thinktanks or marginalised Keynesians in academia, but form part of an agenda being pursued by the International Monetary Fund and the US Treasury under Joe Biden’s presidency.

This matters. From the 1980s onwards, the IMF and the US Treasury forged what became known as the Washington consensus: a set of beliefs that was foisted on any country that ran into economic difficulties and came looking for help. The one-size-fits-all approach involved cutting public spending and taxes, and privatisation, to create incentives for risk-taking entrepreneurs, and making inflation the overriding goal of economic policy. These policies inevitably caused pain, but it was thought the “tough love” approach was worth it.

It has been quite a different story in the buildup to the IMF’s spring meeting this week. Biden’s fast-tracking of a $1.9tn stimulus package through Congress, including direct payments to struggling American families, was significant in two ways. First, at about 10% of the annual output of the US economy, it was much bigger than the emergency support provided by Barack Obama after the global financial crisis of 2008. Second, and perhaps more importantly, it contained no promises of future deficit reduction. Austerity has no part in the thinking of the Biden administration, and nor does the idea that demand fuelled by borrowing inevitably leads to higher inflation.

The next phase in Biden’s plan is to spend a further $2tn on rebuilding America’s crumbling infrastructure. This will be funded by reversing some of Donald Trump’s cut to corporate tax rates, which will be opposed by Republicans in Congress but not by the IMF. When asked about the projected increase this week, the fund’s economic counsellor, Gita Gopinath, said Trump’s corporate tax cut had not done much to boost investment. Moreover, Gopinath was positively enthusiastic about the idea of a global minimum corporate tax rate, something the US has traditionally been wary of but which it now supports.

For the past year, the IMF has been trying to increase the financial firepower of its member countries through currency reserves known as special drawing rights. Trump’s concern that Iran would secure these rights meant there could be no progress while he was in the White House. Under Biden’s treasury secretary, Janet Yellen, the deadlock has been broken and a $650bn special drawing rights allocation has now been announced.

If the old Washington consensus believed in small states, low taxes and balanced budgets, the new Washington consensus believes in activist governments, inclusive growth and a green new deal. Until relatively recently, the only outpost of the multilateral system that supported such ideas was the UN’s trade and development arm in Geneva.

That is no longer the case. This week’s regular IMF update on the state of the global economy emphasises how the pandemic has made pre-existing inequalities worse. That’s true within countries, where the virus and its economic consequences have been toughest on the poor, the young, women and ethnic minorities. It is also true between countries, with the central banks and finance ministries in advanced nations having far more scope to mitigate the impact of lockdowns than those in poorer parts of the world.

Both the IMF and its sister organisation, the World Bank, are clear that there can be no final victory in the battle against Covid-19 until everybody is vaccinated. The problem is not simply that developing countries lack sufficient doses; it is that their health systems are underpowered and lack the trained staff to deliver treatments. Similarly, if the world is to make the transition to a zero-carbon future, developing countries need to be included. That means extra financial resources. All this at a time when fears of a new developing-country debt crisis are rife.

Make no mistake, the IMF is still no soft touch. The conditions imposed as the price for financial support are often draconian, and critics note the disconnect between the right-on rhetoric of the IMF’s managing director, Kristalina Georgieva, and the policies imposed by her organisation’s missions to struggling countries.

Meanwhile, pushback against what Biden has been doing has come from both left and right. Some of the president’s critics accuse him of not being nearly radical enough; others are convinced that all the money creation by the US Federal Reserve and the deficit spending by the US Treasury will inevitably mean much higher inflation. Conjuring up the ghost of economist Milton Friedman, they say it will all eventually end in tears.

For now, though, it is the Friedmanites who look marginalised, with the pandemic accelerating a shift in economic thinking that has been gestating over the past decade. Biden’s approach to running the economy – spending freely and taking a tough line with China – has more in common with that of his immediate predecessor than it does with Obama.

The shift in attitudes has partly been caused by a lack of results. Austerity did not lead to the surge in private investment and faster growth that was promised. Instead, the 2010s were a lost decade of stagnant living standards, which explains why Bidenomics is a big hit with American voters.

Crises also encourage experimentation. Furlough schemes to subsidise the wages of those unable to work are not the same as a basic income, but they are similar enough to get people used to the idea. Necessity rather than ideology explains why Rishi Sunak has spent more than £400bn in the past year on emergency support programmes in the UK, but a Labour chancellor would have done much the same.

There is a sense in which history is repeating itself. It took more than a decade after the end of the first world war for the realisation to dawn that the gold standard was finished. It was the second rather than the first oil shock that opened the door to the economics of the new right in the 1980s. Those who thought that the financial crisis would result in a challenge to the Washington consensus were not wrong. The old nostrums are indeed being questioned. It has just taken 10 years longer than they were expecting, that’s all.

Thursday, 18 February 2021

Why economists kept getting the policies wrong

Philip Stephens in The FT

The other week I caught sight of a headline declaring that the IMF was warning against cuts in public spending and borrowing. The report stopped me in my tracks. After half a century or so as keeper of the sacred flame of fiscal prudence, the IMF was telling policymakers in rich industrial nations they should not fret overmuch about huge build-ups of public debt during the Covid-19 crisis. John Maynard Keynes had been disinterred, and the world turned upside down.

To be clear, there is nothing irresponsible about the IMF’s advice that policymakers in advanced economies should prioritise a restoration of growth after the deflationary shock of the pandemic. The fund prefaced a shift last year, and most people would say it was common sense to allow economic recovery to take hold. Nations such as Britain might have learned that lesson from the damage inflicted by the ill-judged austerity programme imposed by David Cameron’s government after the 2008 financial crash.

And yet. This was the IMF speaking — the hallowed (for some, hated) institution that, as many Brits will recall, formally read the rites over Keynesianism when in 1976 it forced James Callaghan’s Labour government to impose politically calamitous cuts in spending and borrowing. This is the organisation that in the intervening years had a few simple answers to any economic problem you care to think of: fiscal retrenchment, a smaller state and/or market liberalisation. The advice was heralded as the Washington consensus because of the IMF’s location.

My first job after joining the Financial Times during the early 1980s was to learn the language of the new economic orthodoxy. Kindly officials at the UK Treasury explained to me that the technique of using fiscal policy to manage demand, put to rest in 1976, had been replaced by a new theory. Monetarism decreed that as long as the authorities kept control of the money supply, and thus inflation, everything would be fine.

The snag was that every time the Treasury alighted on a particular measure of the money supply to target — sterling M3, PSL2, and M0 come in mind — it ceased to be a reliable guide to price changes. Goodhart’s law, this was called, after the eponymous economist Charles. By the end of the 1980s, monetarism had been ditched, and targeting the exchange rate had become the holy grail. If sterling’s rate was fixed against the Deutschmark, the UK would import stability from Germany.

It was about this time that a senior aide to the chancellor took me to one side to explain that one of the great skills of the Treasury was to perform perfect U-turns while persuading the world it had deviated not a jot from previous policy. This proved its worth again when the exchange rate policy was blown up by sterling’s ejection from the European exchange rate mechanism in 1992. The currency was quickly replaced by an inflation target as an infallible lodestar of policy.

The eternal truths amid the missteps and swerves were that public spending and borrowing were bad, tax cuts were good, and market liberalisation was the route to sunlit uplands. The pound’s ERM debacle was followed by a ferocious budgetary squeeze, and, across the channel, the eurozone was designed to fit a fiscal straitjacket. Financial market deregulation, we were told, oiled the wheels of globalisation. If madcap profits and bonuses at big financial institutions prompted unease, the answer was that markets would self-correct. Britain’s Labour government backed “light-touch” regulation in the 2000s. The Bank of England reduced its oversight of systemic financial stability.

The abiding sin threaded through it all was that of certitude. Perfectly plausible but untested theories, whether about the money supply, fiscal balances and debt levels, or market risk, were elevated to the level of irrefutable facts. Economics, essentially a faith-based discipline, represented itself as a hard science. The real world was reduced by the 1990s to a set of complex mathematical equations that no one, least of all democratically elected politicians, dared challenge.

Thus detached from reality, economic policy swept away the postwar balance between the interests of society and markets. Arid econometrics replaced a measured understanding of political economy. It scarcely mattered that the gains of globalisation were scooped up by the super-rich, that markets became casinos and that fiscal fundamentalism was widening social divisions. Nothing counted above the equations. And now? After Donald Trump, Brexit and Covid-19, it seems we are back at the beginning. Time to dust off Keynes’s general theory.

Monday, 20 July 2020

Saturday, 14 March 2020

This Conservative budget is Keynesian economics reborn

Britain’s national debt over the past decade has always been a non-problem. For most of the last 300 years, it has been very much higher as a share of national output. Our public debt has been well-managed by the Bank of England, so that the average duration of government bonds is 15 years: there is close to zero chance of a crisis of refinancing or of confidence in public debt. At current rates of interest the overall cost of debt service is among the lowest in our history.

Britain has thus plenty of room to spend and borrow, and there was no need for the draconian Cameron-Osborne austerity squeeze in which cumulative cuts in public spending in many areas of government exceeded 40%. Deficit reduction could have been more measured and the pain mitigated. It was baloney from top to bottom – a cruel hoax that was one of the reasons for the Brexit vote, imposing wanton and needless suffering. I and other Keynesian economists have made these arguments in vain for more than a decade – indeed for most of my working life. So Wednesday’s budget was an extraordinary moment.

Chancellor Rishi Sunak repudiated the entire discourse and accepted core Keynesian propositions. He delivered the biggest fiscal boost for nearly 30 years, coordinating it with an interest-rate reduction by the Bank of England – exactly the Keynesian stimulus a flagging economy needed. Public investment was on target to become the highest since 1955, he declared – actually understating the coming public investment boom because in 1955 the comparable figures included investment by the nationalised industries, now nonexistent. The coming wave of investment in roads, rail, housing, schools, further education and ports is unparalleled. It was not just that the investment is needed: he accepted it was part of the government’s role in raising parlously low levels of productivity. Right again.

Yet a rubicon has been crossed. Keynesianism has been restored to its proper place in British public life

Alongside it current public spending is going to rise again, with an additional £12bn package to alleviate the impact of Covid-19. The government would do everything it could to alleviate the spread and impact of the virus. The larger point was that fiscal policy – excusing his party’s volte-face by trying to position it as part of the new international consensus – has got to shoulder its responsibility for driving the economy forward. Amen to that.

Business Today: sign up for a morning shot of financial news

Read more

On the Today programme the following morning my jaw dropped as Sunak informed his audience that reasons for confidence in his package included Britain’s public debt averaging 15 years in duration and debt service costs being extraordinarily low. To make the same argument during the Blair, Cameron and May years was to ensure you wore the mark of Cain – an outlandish Keynesian perspective that branded you as ignorant of the basic laws of economics and public finance. But if a Tory chancellor backed by his press makes the same argument, suddenly it becomes the new economic common sense. To be on the liberal left, as Neil Kinnock once remarked, is to be made to feel an alien outsider – even if reason and a majority of the electorate are with you.

Of course cruel truths remain. The colossal errors of the past decade, Brexit and austerity especially, cannot be expunged at a stroke. Britain’s long-run growth rate is barely above 1% as the Office for Budget Responsibility recorded. The impact of Brexit, it declared, would be to lower output over the next 15 years by 5.2% below what it would have been. The much-vaunted US trade deal, if it ever happens, will raise output by a mere 0.16%. Over the next decade exports and imports will be 15% lower. Britain, tragically, is closing – and becoming more intolerant and anti-foreigner in the process.

Nor can the social carnage of the past decade be quickly corrected. Sunak did little or nothing to address child poverty, the desperate plight of the court and criminal justice system or a host of other casualties. This was government from the centre for the centre: local government remained a neglected Cinderella. The increase in current public spending will redress only about a quarter of the cumulative loss in health and education spending since 2010.

Yet a Rubicon has been crossed. Keynesianism has been restored to its proper place in British public life. The Conservatives have once again shown their breathtaking and shameless capacity for reinvention. If Labour wants to trump them, it will need to take Keynesianism even further – into the wholesale Keynesian recasting of the way the financial system intersects with the real economy.

In the meantime it’s a big moment. Perhaps in this respect – and this only – Labour did win an argument at the last election. At the very least a new and beneficial consensus has been born.

Thursday, 13 December 2018

My plan to revive Europe can succeed where Macron and Piketty failed

If Brexit demonstrates that leaving the EU is not the walk in the park that Eurosceptics promised, Emmanuel Macron’s current predicament proves that blind European loyalism is, similarly, untenable. The reason is that the EU’s architecture is equally difficult to deconstruct, sustain and reform.

While Britain’s political class is, rightly, in the spotlight for having made a mess of Brexit, the EU’s establishment is in a similar bind over its colossal failure to civilise the eurozone – with the rise of the xenophobic right the hideous result.

Macron was the European establishment’s last hope. As a presidential candidate, he explicitly recognised that “if we don’t move forward, we are deciding the dismantling of the eurozone”, the penultimate step before dismantling of the EU itself. Never shy of offering details, Macron defined a minimalist reform agenda for saving the European project: a common bank deposit insurance scheme (to end the chronic doom loop between insolvent banks and states); a well-funded common treasury (to fund pan-European investment and unemployment benefits); and a hybrid parliament (comprising national and European members of parliament to lend democratic legitimacy to all of the above).

Since his election, the French president has attempted a two-phase strategy: “Germanise” France’s labour market and national budget (essentially making it easier for employers to fire workers while ushering in additional austerity) so that, in the second phase, he might convince Angela Merkel to persuade the German political class to sign up to his minimalist eurozone reform agenda. It was a spectacular miscalculation – perhaps greater than Theresa May’s error in accepting the EU’s two-phase approach to Brexit negotiations.

When Berlin gets what it wants in the first phase of any negotiation, German chancellors then prove either unwilling or incapable of conceding anything of substance in the second phase. Thus, just like May ending up with nothing tangible in the second phase (the political declaration) by which to compensate her constituents for everything she gave up in the first phase (the withdrawal agreement), so Macron saw his eurozone reform agenda evaporate once he had attempted to Germanise France’s labour and national budget. The subsequent fall from grace, at the hands of the offspring of his austerity drive – the gilets jaunes movement – was inevitable.

The great advantage of our Green New Deal is we are taking a leaf out of Franklin Roosevelt’s original New Deal in the 1930s

Historians will mark Macron’s failure as a turning point in the EU, perhaps one that is more significant than Brexit: it puts an end to the French ambition for a fiscal union with Germany. We can already see the decline of this French reformist ambition in the shape of the latest manifesto for saving Europe by the economist Thomas Piketty and his supporters – published this week. Professor Piketty has been active in producing eurozone reform agendas for a number of years – an earlier manifesto was produced in 2014. It is, therefore, interesting to observe the effect of recent European developments on his proposals.

In 2014, Piketty put forward three main proposals: a common eurozone budget funded by harmonised corporate taxes to be transferred to poorer countries in the form of investment, research and social spending; the pooling of public debt, which would mean the likes of Germany and Holland helping Italy, Greece and others in a similar situation to bring down their debt; and a hybrid parliamentary chamber. In short, something similar to Macron’s now shunned European agenda.

Four years later, the latest Piketty manifesto retains a hybrid parliamentary chamber, but forfeits any Europeanist ambition – all proposals for debt pooling, risk sharing and fiscal transfers have been dropped. Instead, it suggests that national governments agree to raise €800bn (or 4% of eurozone GDP) through a harmonised corporate tax rate of 37%, an increased income tax rate for the top 1%, a new wealth tax for those with more than €1m in assets, and a C02 emissions tax of €30 per tonne. This money would then be spent within each nation-state that collected it – with next to no transfers across countries. But, if national money is to be raised and spent domestically, what is the point of another supranational parliamentary chamber?

Europe is weighed down by overgrown, quasi-insolvent banks, fiscally stressed states, irate German savers crushed by negative interest rates, and whole populations immersed in permanent depression: these are all symptoms of a decade-long financial crisis that has produced a mountain of savings sitting alongside a mountain of debts. The intention of taxing the rich and the polluters to fund innovation, migrants and the green transition is admirable. But it is insufficient to tackle Europe’s particular crisis.

What Europe needs is a Green New Deal – this is what Democracy in Europe Movement 2025 – which I co-founded – and our European Spring alliance will be taking to voters in the European parliament elections next summer.

The great advantage of our Green New Deal is that we are taking a leaf out of US President Franklin Roosevelt’s original New Deal in the 1930s: our idea is to create €500bn every year in the green transition across Europe, without a euro in new taxes.

Here’s how it would work: the European Investment Bank (EIB) issues bonds of that value with the European Central Bank standing by, ready to purchase as many of them as necessary in the secondary markets. The EIB bonds will undoubtedly sell like hot cakes in a market desperate for a safe asset. Thus, the excess liquidity that keeps interest rates negative, crushing German pension funds, is soaked up and the Green New Deal is fully funded.

Once hope in a Europe of shared, green prosperity is restored, it will be possible to have the necessary debate on new pan-European taxes on C02, the rich, big tech and so on – as well as settling the democratic constitution Europe deserves.

Perhaps our Green New Deal may even create the climate for a second UK referendum, so that the people of Britain can choose to rejoin a better, fairer, greener, democratic EU.

Wednesday, 25 October 2017

The Nature of Money, Modern Money and Bitcoin

Friday, 15 April 2016

Neoliberalism – the ideology at the root of all our problems

Imagine if the people of the Soviet Union had never heard of communism. The ideology that dominates our lives has, for most of us, no name. Mention it in conversation and you’ll be rewarded with a shrug. Even if your listeners have heard the term before, they will struggle to define it. Neoliberalism: do you know what it is?

Its anonymity is both a symptom and cause of its power. It has played a major role in a remarkable variety of crises: the financial meltdown of 2007‑8, the offshoring of wealth and power, of which the Panama Papers offer us merely a glimpse, the slow collapse of public health and education, resurgent child poverty, the epidemic of loneliness, the collapse of ecosystems, the rise of Donald Trump. But we respond to these crises as if they emerge in isolation, apparently unaware that they have all been either catalysed or exacerbated by the same coherent philosophy; a philosophy that has – or had – a name. What greater power can there be than to operate namelessly?

So pervasive has neoliberalism become that we seldom even recognise it as an ideology. We appear to accept the proposition that this utopian, millenarian faith describes a neutral force; a kind of biological law, like Darwin’s theory of evolution. But the philosophy arose as a conscious attempt to reshape human life and shift the locus of power.

Neoliberalism sees competition as the defining characteristic of human relations. It redefines citizens as consumers, whose democratic choices are best exercised by buying and selling, a process that rewards merit and punishes inefficiency. It maintains that “the market” delivers benefits that could never be achieved by planning.

Attempts to limit competition are treated as inimical to liberty. Tax and regulation should be minimised, public services should be privatised. The organisation of labour and collective bargaining by trade unions are portrayed as market distortions that impede the formation of a natural hierarchy of winners and losers. Inequality is recast as virtuous: a reward for utility and a generator of wealth, which trickles down to enrich everyone. Efforts to create a more equal society are both counterproductive and morally corrosive. The market ensures that everyone gets what they deserve.

We internalise and reproduce its creeds. The rich persuade themselves that they acquired their wealth through merit, ignoring the advantages – such as education, inheritance and class – that may have helped to secure it. The poor begin to blame themselves for their failures, even when they can do little to change their circumstances.

Never mind structural unemployment: if you don’t have a job it’s because you are unenterprising. Never mind the impossible costs of housing: if your credit card is maxed out, you’re feckless and improvident. Never mind that your children no longer have a school playing field: if they get fat, it’s your fault. In a world governed by competition, those who fall behind become defined and self-defined as losers.

Among the results, as Paul Verhaeghe documents in his book What About Me? are epidemics of self-harm, eating disorders, depression, loneliness, performance anxiety and social phobia. Perhaps it’s unsurprising that Britain, in which neoliberal ideology has been most rigorously applied, is the loneliness capital of Europe. We are all neoliberals now.

***

The term neoliberalism was coined at a meeting in Paris in 1938. Among the delegates were two men who came to define the ideology, Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek. Both exiles from Austria, they saw social democracy, exemplified by Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal and the gradual development of Britain’s welfare state, as manifestations of a collectivism that occupied the same spectrum as nazism and communism.

In The Road to Serfdom, published in 1944, Hayek argued that government planning, by crushing individualism, would lead inexorably to totalitarian control. Like Mises’s book Bureaucracy, The Road to Serfdom was widely read. It came to the attention of some very wealthy people, who saw in the philosophy an opportunity to free themselves from regulation and tax. When, in 1947, Hayek founded the first organisation that would spread the doctrine of neoliberalism – the Mont Pelerin Society – it was supported financially by millionaires and their foundations.

With their help, he began to create what Daniel Stedman Jones describes inMasters of the Universe as “a kind of neoliberal international”: a transatlantic network of academics, businessmen, journalists and activists. The movement’s rich backers funded a series of thinktanks which would refine and promote the ideology. Among them were the American Enterprise Institute, the Heritage Foundation, the Cato Institute, the Institute of Economic Affairs, the Centre for Policy Studies and the Adam Smith Institute. They also financed academic positions and departments, particularly at the universities of Chicago and Virginia.

As it evolved, neoliberalism became more strident. Hayek’s view that governments should regulate competition to prevent monopolies from forming gave way – among American apostles such as Milton Friedman – to the belief that monopoly power could be seen as a reward for efficiency.

Something else happened during this transition: the movement lost its name. In 1951, Friedman was happy to describe himself as a neoliberal. But soon after that, the term began to disappear. Stranger still, even as the ideology became crisper and the movement more coherent, the lost name was not replaced by any common alternative.

At first, despite its lavish funding, neoliberalism remained at the margins. The postwar consensus was almost universal: John Maynard Keynes’s economic prescriptions were widely applied, full employment and the relief of poverty were common goals in the US and much of western Europe, top rates of tax were high and governments sought social outcomes without embarrassment, developing new public services and safety nets.

But in the 1970s, when Keynesian policies began to fall apart and economic crises struck on both sides of the Atlantic, neoliberal ideas began to enter the mainstream. As Friedman remarked, “when the time came that you had to change ... there was an alternative ready there to be picked up”. With the help of sympathetic journalists and political advisers, elements of neoliberalism, especially its prescriptions for monetary policy, were adopted by Jimmy Carter’s administration in the US and Jim Callaghan’s government in Britain.

After Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan took power, the rest of the package soon followed: massive tax cuts for the rich, the crushing of trade unions, deregulation, privatisation, outsourcing and competition in public services. Through the IMF, the World Bank, the Maastricht treaty and the World Trade Organisation, neoliberal policies were imposed – often without democratic consent – on much of the world. Most remarkable was its adoption among parties that once belonged to the left: Labour and the Democrats, for example. As Stedman Jones notes, “it is hard to think of another utopia to have been as fully realised.”

***

It may seem strange that a doctrine promising choice and freedom should have been promoted with the slogan “there is no alternative”. But, as Hayek remarked on a visit to Pinochet’s Chile – one of the first nations in which the programme was comprehensively applied – “my personal preference leans toward a liberal dictatorship rather than toward a democratic government devoid of liberalism”. The freedom that neoliberalism offers, which sounds so beguiling when expressed in general terms, turns out to mean freedom for the pike, not for the minnows.

Freedom from trade unions and collective bargaining means the freedom to suppress wages. Freedom from regulation means the freedom to poison rivers, endanger workers, charge iniquitous rates of interest and design exotic financial instruments. Freedom from tax means freedom from the distribution of wealth that lifts people out of poverty.

Naomi Klein documented that neoliberals advocated the use of crises to impose unpopular policies while people were distracted. Photograph: Anya Chibis for the Guardian

As Naomi Klein documents in The Shock Doctrine, neoliberal theorists advocated the use of crises to impose unpopular policies while people were distracted: for example, in the aftermath of Pinochet’s coup, the Iraq war and Hurricane Katrina, which Friedman described as “an opportunity to radically reform the educational system” in New Orleans.

Where neoliberal policies cannot be imposed domestically, they are imposed internationally, through trade treaties incorporating “investor-state dispute settlement”: offshore tribunals in which corporations can press for the removal of social and environmental protections. When parliaments have voted to restrict sales of cigarettes, protect water supplies from mining companies, freeze energy bills or prevent pharmaceutical firms from ripping off the state, corporations have sued, often successfully. Democracy is reduced to theatre.

Another paradox of neoliberalism is that universal competition relies upon universal quantification and comparison. The result is that workers, job-seekers and public services of every kind are subject to a pettifogging, stifling regime of assessment and monitoring, designed to identify the winners and punish the losers. The doctrine that Von Mises proposed would free us from the bureaucratic nightmare of central planning has instead created one.

Neoliberalism was not conceived as a self-serving racket, but it rapidly became one. Economic growth has been markedly slower in the neoliberal era (since 1980 in Britain and the US) than it was in the preceding decades; but not for the very rich. Inequality in the distribution of both income and wealth, after 60 years of decline, rose rapidly in this era, due to the smashing of trade unions, tax reductions, rising rents, privatisation and deregulation.

The privatisation or marketisation of public services such as energy, water, trains, health, education, roads and prisons has enabled corporations to set up tollbooths in front of essential assets and charge rent, either to citizens or to government, for their use. Rent is another term for unearned income. When you pay an inflated price for a train ticket, only part of the fare compensates the operators for the money they spend on fuel, wages, rolling stock and other outlays. The rest reflects the fact that they have you over a barrel.

In Mexico, Carlos Slim was granted control of almost all phone services and soon became the world’s richest man. Photograph: Henry Romero/Reuters

Those who own and run the UK’s privatised or semi-privatised services make stupendous fortunes by investing little and charging much. In Russia and India, oligarchs acquired state assets through firesales. In Mexico, Carlos Slim was granted control of almost all landline and mobile phone services and soon became the world’s richest man.

Financialisation, as Andrew Sayer notes in Why We Can’t Afford the Rich, has had a similar impact. “Like rent,” he argues, “interest is ... unearned income that accrues without any effort”. As the poor become poorer and the rich become richer, the rich acquire increasing control over another crucial asset: money. Interest payments, overwhelmingly, are a transfer of money from the poor to the rich. As property prices and the withdrawal of state funding load people with debt (think of the switch from student grants to student loans), the banks and their executives clean up.

Sayer argues that the past four decades have been characterised by a transfer of wealth not only from the poor to the rich, but within the ranks of the wealthy: from those who make their money by producing new goods or services to those who make their money by controlling existing assets and harvesting rent, interest or capital gains. Earned income has been supplanted by unearned income.

Neoliberal policies are everywhere beset by market failures. Not only are the banks too big to fail, but so are the corporations now charged with delivering public services. As Tony Judt pointed out in Ill Fares the Land, Hayek forgot that vital national services cannot be allowed to collapse, which means that competition cannot run its course. Business takes the profits, the state keeps the risk.

The greater the failure, the more extreme the ideology becomes. Governments use neoliberal crises as both excuse and opportunity to cut taxes, privatise remaining public services, rip holes in the social safety net, deregulate corporations and re-regulate citizens. The self-hating state now sinks its teeth into every organ of the public sector.

Perhaps the most dangerous impact of neoliberalism is not the economic crises it has caused, but the political crisis. As the domain of the state is reduced, our ability to change the course of our lives through voting also contracts. Instead, neoliberal theory asserts, people can exercise choice through spending. But some have more to spend than others: in the great consumer or shareholder democracy, votes are not equally distributed. The result is a disempowerment of the poor and middle. As parties of the right and former left adopt similar neoliberal policies, disempowerment turns to disenfranchisement. Large numbers of people have been shed from politics.

Slogans, symbols and sensation … Donald Trump. Photograph: Aaron Josefczyk/Reuters

Chris Hedges remarks that “fascist movements build their base not from the politically active but the politically inactive, the ‘losers’ who feel, often correctly, they have no voice or role to play in the political establishment”. When political debate no longer speaks to us, people become responsive instead to slogans, symbols and sensation. To the admirers of Trump, for example, facts and arguments appear irrelevant.

Judt explained that when the thick mesh of interactions between people and the state has been reduced to nothing but authority and obedience, the only remaining force that binds us is state power. The totalitarianism Hayek feared is more likely to emerge when governments, having lost the moral authority that arises from the delivery of public services, are reduced to “cajoling, threatening and ultimately coercing people to obey them”.

***

Like communism, neoliberalism is the God that failed. But the zombie doctrine staggers on, and one of the reasons is its anonymity. Or rather, a cluster of anonymities.

The invisible doctrine of the invisible hand is promoted by invisible backers. Slowly, very slowly, we have begun to discover the names of a few of them. We find that the Institute of Economic Affairs, which has argued forcefully in the media against the further regulation of the tobacco industry, has been secretly funded by British American Tobacco since 1963. We discover that Charles and David Koch, two of the richest men in the world, founded the institute that set up the Tea Party movement. We find that Charles Koch, in establishing one of his thinktanks, noted that “in order to avoid undesirable criticism, how the organisation is controlled and directed should not be widely advertised”.

The words used by neoliberalism often conceal more than they elucidate. “The market” sounds like a natural system that might bear upon us equally, like gravity or atmospheric pressure. But it is fraught with power relations. What “the market wants” tends to mean what corporations and their bosses want. “Investment”, as Sayer notes, means two quite different things. One is the funding of productive and socially useful activities, the other is the purchase of existing assets to milk them for rent, interest, dividends and capital gains. Using the same word for different activities “camouflages the sources of wealth”, leading us to confuse wealth extraction with wealth creation.

A century ago, the nouveau riche were disparaged by those who had inherited their money. Entrepreneurs sought social acceptance by passing themselves off as rentiers. Today, the relationship has been reversed: the rentiers and inheritors style themselves entre preneurs. They claim to have earned their unearned income.

These anonymities and confusions mesh with the namelessness and placelessness of modern capitalism: the franchise model which ensures that workers do not know for whom they toil; the companies registered through a network of offshore secrecy regimes so complex that even the police cannot discover the beneficial owners; the tax arrangements that bamboozle governments; the financial products no one understands.

The anonymity of neoliberalism is fiercely guarded. Those who are influenced by Hayek, Mises and Friedman tend to reject the term, maintaining – with some justice – that it is used today only pejoratively. But they offer us no substitute. Some describe themselves as classical liberals or libertarians, but these descriptions are both misleading and curiously self-effacing, as they suggest that there is nothing novel about The Road to Serfdom, Bureaucracy or Friedman’s classic work, Capitalism and Freedom.

***

For all that, there is something admirable about the neoliberal project, at least in its early stages. It was a distinctive, innovative philosophy promoted by a coherent network of thinkers and activists with a clear plan of action. It was patient and persistent. The Road to Serfdom became the path to power.

Neoliberalism’s triumph also reflects the failure of the left. When laissez-faire economics led to catastrophe in 1929, Keynes devised a comprehensive economic theory to replace it. When Keynesian demand management hit the buffers in the 70s, there was an alternative ready. But when neoliberalism fell apart in 2008 there was ... nothing. This is why the zombie walks. The left and centre have produced no new general framework of economic thought for 80 years.

Every invocation of Lord Keynes is an admission of failure. To propose Keynesian solutions to the crises of the 21st century is to ignore three obvious problems. It is hard to mobilise people around old ideas; the flaws exposed in the 70s have not gone away; and, most importantly, they have nothing to say about our gravest predicament: the environmental crisis. Keynesianism works by stimulating consumer demand to promote economic growth. Consumer demand and economic growth are the motors of environmental destruction.

What the history of both Keynesianism and neoliberalism show is that it’s not enough to oppose a broken system. A coherent alternative has to be proposed. For Labour, the Democrats and the wider left, the central task should be to develop an economic Apollo programme, a conscious attempt to design a new system, tailored to the demands of the 21st century.