'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Monday, 5 August 2024

Wednesday, 1 May 2024

Economics is in Disarray: Time to Rethink

The Guardian View

When Labour’s Gordon Brown embraced “post neo-classical endogenous growth theory” in 1994, he was ridiculed by his opponents. This said more about his critics than Mr Brown. His speech reflected an engagement with academic debates as well as a worldview and diagnosis distinct from Tory narratives. He judged education to be key, as growth depended on human capital. By contrast, today Labour’s top team struggles to say exactly what they believe will drive growth and how they will achieve it.

Part of the reason is that mainstream economics is proving incapable of giving sensible answers to important questions. Whether it is the financial crash, the pandemic or inflation shocks, the response is that spending cuts are needed as public debt threatens to bankrupt the nation. Many economists are questioning their discipline’s worth. Last month, the Nobel laureate Angus Deaton blogged that economics was in “disarray” and had “largely stopped thinking about ethics”. Jeremy Rudd of the US Federal Reserve writes scornfully in his latest book, A Practical Guide to Macroeconomics, that economists’ role today is to justify “what elite interests want to do anyway: deregulate, pay fewer taxes, keep wages as low as possible”.

One school of thought attempting to rewrite the textbooks is called modern monetary theory, whose face is Stephanie Kelton, a former economic adviser to Bernie Sanders. She argues that there is no financial constraint on government spending; money can be created and invested so long as there is capacity in the economy to absorb the cash. If not, inflation will follow. This shouldn’t be controversial. John Maynard Keynes said as much in his 1940 book, How to Pay for the War. The theory is not just about deficits: a strong exporting nation should pursue fiscal surpluses – an insight attributed to Prof Kelton’s tutor and ex-Treasury adviser Wynne Godley.

Her work made headlines during Covid-19, when governments spent big without asking first where the money would come from. Prof Kelton’s book The Deficit Myth became a bestseller. Next month, a movie, Finding the Money, hits US screens. The film looks at why politicians hide behind economic “myths” rather than explain to voters the trade-offs required to help them. Prof Kelton’s positions are often counterintuitive, which makes them interesting. Her current argument that rising US interest rates might be inflationary finds her agreeing with her sharpest critic, Larry Summers. Such challenges should be welcome in Britain. The US debates have produced an industrial policy powered by government deficits – and the world’s fastest growing advanced economy.

Mr Brown’s successor Rachel Reeves prefers a deadening consensus, sacrificing policies to placate business while committing to Tory spending now that is “paid for” by austerity later. Both major parties say deregulation would crowd in private investment and the state could capture the ensuing productivity gains. The Tories would use the proceeds for tax cuts whereas Labour would spend them on public services. This strategy has failed since 2010. Why would it work now? One of Ms Reeves’ predecessors said that “the history of British policymaking in the last hundred years has taught us that on all the other occasions when major economic misjudgments were made, broad-based political, media, financial and popular opinion was in favour of the decision at the time, and the dissenting voices of economists were silenced or ignored”. Ed Balls’ 2011 speech is as relevant today as it was then.

Thursday, 5 October 2023

Friday, 10 December 2021

Spending without taxing: now we’re all guinea pigs in an endless money experiment

Today, citizens are unwitting participants in a covert policy experiment. It embraces the idea of higher government spending without the necessity of increased taxes. While modern monetary theory (MMT), the doctrine, has obvious appeal for politicians, irrespective of economic religion, the long-term consequences may prove problematic.

A state, MMT argues, finances its spending by creating money, not from taxes or borrowing. As nations cannot go bankrupt when they can print their own currency, deficits and debt don’t matter. Accordingly, governments should spend to ensure full employment, guaranteeing a job for everyone willing to work. Alternatively, though not formally part of MMT, governments can fund universal basic income (UBI) schemes, providing every individual an unconditional flat-rate payment irrespective of circumstances.

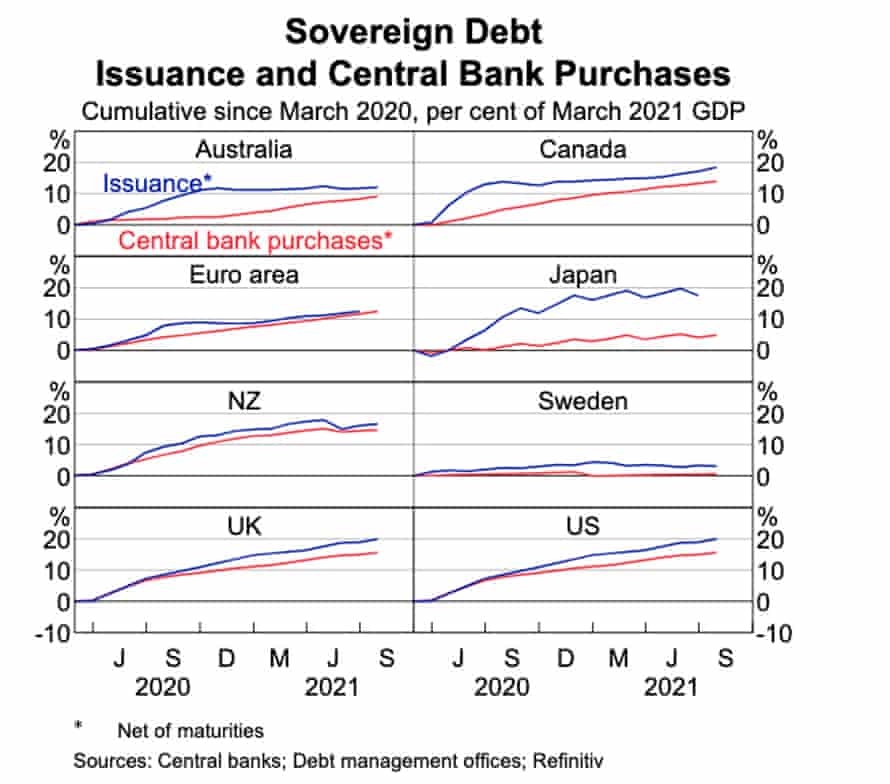

While no government or central bank overtly advocates MMT, since the 2008 global financial crisis and, more recently, the pandemic, policymakers have adopted many of its tenets by stealth. Popular one-off payments and increased welfare entitlements, which could become permanent, increasingly support economic activity. As the graph below highlights, central banks now buy a high percentage of new government debt, effectively financing this additional spending by money creation.

Source: Nick Baker, Marcus Miller and Ewan Rankin (2021 September) Government Bond Markets in Advanced Economies During the Pandemic; Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletin

MMT is actually a melange of old ideas: Keynesian deficit spending; the post gold standard ability of nations to create money at will; and quantitative easing (central bank financed government spending) pioneered by Japan. However, there are several concerns about MMT.

First, the source of useful, well-compensated work is unclear. While MMT suggests taxes can be used to direct production, government influence over businesses that create jobs is limited. The impact of labour-reducing technology and competitive global supply chains is glossed over. Getting one person to dig a hole and another to fill it in creates employment, but it is of doubtful economic and social value. The woeful record of postwar centrally planned economies, where people pretended to work and the government pretended to pay them, highlights the issues.

Second, excess government spending and large deficits financed by money creation risk creating inflation. MMT argues that this is a risk only where the economy is at full employment or there is no excess capacity, and can be managed by fine-tuning intervention.

Third, MMT may weaken the currency. Roughly half of Australia’s government and significant amounts of state, bank and business debt is held by foreigners. Devaluation and loss of investor confidence in the stability of the exchange rate would affect the ability to and cost of borrowing overseas and importing goods. The expense of servicing foreign currency debt would rise.

Fourth, while available to nation states able to issue their own fiat currencies, it is unavailable to state governments, private businesses or households who are major borrowers in Australia.

Fifth, who decides the target employment rate or UBI payment level? Unemployment, inflation and output gaps are difficult to accurately measure in practice. Effects on employment incentives, workforce participation and productivity are untested. How will policymakers control the process or what would happen if MMT failed?

The theory delegates management of MMT operations to politicians, rather than unelected economic mandarins. But financially challenged elected representatives may be poorly equipped for the task. Political considerations and cronyism may influence decisions.

Sixth, there are implications for financial stability. Lower rates, the result of central bank debt purchases, and inflation fears might drive a switch to real assets, increasing the price of property and shares representing claims on underlying cashflows. It may encourage hoarding of commodities. This exacerbates inequality and increases the cost of essentials such as food, fuel and shelter. Fear of debasement of the value of paper money, in part, is behind unproductive speculation in gold and cryptocurrencies.

Seventh, MMT might undermine trust in the currency. Instead of spending the payments, citizens may question a world where governments print money and throw it out of helicopters.

Finally, Japan’s use of persistent deficits to boost short-term economic activity and incur government debt (currently more than 260% of GDP, compared with a global average of about 100%) does not prove the effectiveness of MMT. The country’s circumstances are unique and it has been mired in stagnation for three decades with its GDP largely unchanged.

MMT’s allure is the irresistible promise of freebies; full employment, unlimited higher education, healthcare and government services, state-of-the-art infrastructure, green energy and “the colonisation of Mars”. But monetary manipulation cannot change the supply of real goods and services or overcome resource constraints, otherwise prosperity and utopia would be guaranteed.

While the current game can and will continue for a time, the bill will eventually arrive. The borrowings will have to be paid for out of disposable income, higher taxes or through inflation, which reduces purchasing power, especially of the most vulnerable, and destroys savings. Other than nature’s free bounty, everything has a cost.

Thursday, 22 October 2020

The case against Modern Monetary Theory

Stephen King in The FT

In a world in which government debt is rapidly rising, it’s hardly surprising that there’s growing interest among investors in Modern Monetary Theory. After all, one of its central claims is that budget deficits are, from a financing perspective, an irrelevance. So long as increased government borrowing doesn’t lead to inflation — and, at the moment, there really isn’t much of it around — we can all afford to relax.

As Stephanie Kelton notes in her book The Deficit Myth, governments with access to a printing press are “currency issuers” (exceptions include, most obviously, members of the eurozone). As such, all their spending could, in principle, be financed via the creation of cash. Taxes may serve other purposes — the redistribution of income and wealth, the discouragement of “sinful” behaviour — but, in the world of MMT, they serve no useful macroeconomic role.

---Also read

Can governments afford the debts they are piling up?

The magic money tree does exist, according to modern monetary theory

---

In the real world, however, taxes are crucial. The fundamental difference between government finances and those of companies and households is not access to a printing press but, instead, the coercive power to raise taxes. A company making a severe loss cannot reduce that loss by imposing taxes on everyone else. A government can. A worker receiving a pay cut cannot force others to make up the difference. A government can.

Armed with this knowledge, creditors are understandably willing to accept mostly lower returns on government bonds than on other investments. Put simply, the risk of government default in the face of an adverse economic shock is lower than for other would-be borrowers.

Admittedly, there are limits, dictated largely by the political capacity of a government to raise revenues in difficult circumstances. Emerging markets often end up resorting instead to devaluation, default or inflation. In anticipation, borrowing costs spike.

Still, imagine for a moment that governments embrace MMT. Imagine too, as MMT proponents suggest, that control of the printing press is taken away from unelected central bankers and given to “accountable” elected fiscal representatives. Would we be any better off?

Far from it. Giving elected representatives the keys to the printing press is the equivalent of giving a gambling addict the keys to the casino. For many politicians, the primary objective is to remain in power. As such, they will too often be incentivised to pursue instant gratification at the expense of longer-term stability. In the early-1970s, the UK embarked on what became known as the “Barber boom”, thanks to the efforts of Conservative chancellor of the exchequer Anthony Barber to engineer an election victory in 1974. As it turned out, the Tories lost and, two years later, the UK ignominiously had to accept a bailout from the IMF. Central bank independence provides a useful bulwark against such behaviour.

More importantly, inflation and taxes are, in many ways, simply two sides of the same coin. Those governments without access to tax revenues can instead “debase the coinage”. Supporters of MMT claim this will never happen, yet history suggests otherwise: after all, it has been a tried and tested policy of kings and queens over hundreds of years. Too often, those with access to the printing press are prepared to take undue risks in the hope that “this time it’s different”.

In truth, inflation helps solve the financing issues that proponents of MMT claim no longer exist. Negative real interest rates, a result of higher-than-anticipated inflation, serve to redistribute wealth away from private creditors (pensioners, for example) to public debtors. Much the same could be achieved through a wealth tax. At this point, we come full circle: the distinction between the printing press and taxes begins to break down.

Thanks to Covid-19, government debt is rising rapidly and, for that matter, appropriately. In the face of recurring lockdowns, we are better off allowing companies and workers to enter a period of economic “hibernation” in the hope that, once the virus is under control, they can thaw out. The alternative of multiple business failures and mass unemployment is of no use to anyone. In the process, however, we are in effect borrowing from our collective economic futures. At some point, some of us will be presented with a bill which, if hibernation policies succeed, we will be in a reasonable position to pay. The political process will decide whether that bill comes in the form of higher taxes, more austerity, rising inflation or eventual default. That, I’m afraid, is the deficit reality.

Monday, 4 May 2020

Can governments afford the debts they are piling up to stabilise economies?

Stephanie Kelton and Edward Chancellor in The FT

YES - It poses no inherent danger to states that issue their own currency

The Covid-19 pandemic has forced governments around the world to spend large sums in an effort to stabilise their economies, writes Stephanie Kelton. Gone, for now, are concerns about how to “pay for” it all. Instead we are seeing wartime levels of spending, driving deficits — and public debt — to new highs.

France, Spain, the US, and the UK are all projected to end the year with public debt levels of more than 100 per cent of gross domestic product, while Goldman Sachs predicts that Italy’s debt-to-GDP ratio will soar above 160 per cent. In Japan, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has committed to nearly $1tn in new deficit spending to protect a $5tn economy, a move that will push Japan’s debt ratio well above its record of 237 per cent. With GDP collapsing on a global scale, few countries will escape. In advanced economies, the IMF expects average debt-to-GDP ratios to be above 120 per cent in 2021.

While most see big deficits as a price worth paying to combat the crisis, many worry about a debt overhang in a post-pandemic world. Some fear that investors will grow weary of lending to cash-strapped governments, forcing countries to borrow at higher interest rates. Others worry governments will need to impose painful austerity in the years ahead, requiring the private sector to tighten its belt to pay down public debt. They should not.

While public debt can create problems in certain circumstances, it poses no inherent danger to currency-issuing governments, such as the US, Japan, or the UK. This is not, as some argue, because these countries can currently borrow at very low cost, or because a strong recovery will allow them to grow their way out of debt.

There are three real reasons. First, a currency-issuing government never needs to borrow its own currency. Second, it can always determine the interest rate on bonds it chooses to sell. Third, government bonds help to shore up the private sector’s finances.

The first point should be obvious, but it is often obscured by the way governments manage their fiscal operations. Take Japan, a country with its own sovereign currency. To spend more, Tokyo simply authorises payments and the Bank of Japan uses the computer to increase the quantity of Yen in the bank account. Being the issuer of a sovereign currency means never having to worry about how you are going to pay your bills. The Japanese government can afford to buy whatever is available for sale in its own currency. True, it can spend too much, fuelling inflationary pressure, but it never needs to borrow Yen.

If that is true, why do governments sell bonds whenever they run deficits? Why not just spend without adding to the national debt? It is an important question. Part of the reason is habit. Under a gold standard, governments sold bonds so deficits would not leave too much currency in people’s hands. Borrowing replaced currency (which was convertible into gold) with government bonds which were not. In other words, countries sold bonds to reduce pressure on their gold reserves. But that’s not why they borrow in the modern era.

Today, borrowing is voluntary, at least for countries with sovereign currencies. Sovereign bonds are just an interest-bearing form of government money. The UK, for example, is under no obligation to offer an interest-bearing alternative to its zero-interest currency, nor must it pay market rates when it borrows. As Japan has demonstrated with yield curve control, the interest rate on government bonds is a policy choice.

So today, governments sell bonds to protect something more valuable than gold: a well-guarded secret about the true nature of their fiscal capacities, which, if widely understood, might lead to calls for “overt monetary financing” to pay for public goods. By selling bonds, they maintain the illusion of being financially constrained.

In truth, currency-issuing governments can safely spend without borrowing. The debt overhang that many are worried about can be avoided. That is not to say that there is anything wrong with offering people an interest-bearing alternative to government currency. Bonds are a gift to investors, not a sign of dependency on them. The question we should be debating, then, is how much “interest income” should governments be paying out, and to whom?

The writer is a professor of economics and public policy at Stony Brook University and author of the forthcoming book “The Deficit Myth”

No — This dangerous monetary practice ensures inflation is around the corner

How to pay for the fathomless costs of fighting a pandemic? All the state’s expenses, whether a Green New Deal, jobs-for-all or the economic lockdowns, can be met simply by printing money. That is what modern monetary theory claims, writes Edward Chancellor.

Adherents of this unorthodox school of economics would have us believe, like Alice in Wonderland, six impossible things before breakfast. Governments can never go bust. They don’t need to raise taxes or issue bonds to finance themselves. Borrowing creates savings. Fiscal deficits are not the problem, they are the cure. We could even pay off the national debt tomorrow.

As theory, MMT has been rejected by mainstream economists. But as a matter of practical policy, it is already being deployed. Ever since Ben Bernanke, as governor of the US Federal Reserve, delivered his “helicopter money” speech in November 2002, the world has been moving in this direction. As president of the European Central Bank, Mario Draghi proved that even the most indebted countries need not default. Last year, the US federal deficit exceeded $1tn at a time when the Fed was acquiring Treasuries with newly printed dollars — that’s pure MMT.

This crisis has accelerated the process. Fiscal and monetary policy are now being openly co-ordinated, just as MMT recommends. The US budget deficit is set to reach nearly $4tn this year. But tax rises are not on the agenda. Instead, the Fed will write the cheques. Across the Atlantic, the Bank of England is directly financing the largest peacetime deficit in its history. MMT claims that money is a creature of the state. The Fed’s share of an expanding US money supply is close to 40 per cent and rising. Again, we are seeing MMT in practice.

The lockdown is a propitious moment to implement MMT. During crises, the public has an abnormally high demand to hold cash; debt monetisation appears less of a problem. But governments can print money to cover their costs for only as long as the public retains confidence in a currency. When the crisis passes, the excess money must be mopped up.

Proponents of MMT claim this shouldn’t be a problem. But then they admit that nobody has a good inflation model. We cannot accurately measure the economy’s spare capacity, either. This means that politicians are unlikely to raise taxes in time to nip inflation in the bud. Bonds can always be issued to withdraw money from circulation. But once inflation is under way, bondholders demand higher coupons. From a fiscal perspective, it makes more sense to issue government debt when rates are low — as they are today — than to print money now and pay higher rates later.

Great historic inflations have been caused not by monetary excesses but by supply shocks, say MMT exponents. It’s likely that coronavirus will turn out to be one of those shocks. Besides, history casts doubt on attempts to explain inflation by non-monetary factors. The closest example of MMT in implementation comes from France’s experiment with paper money. In 1720, the Scottish adventurer John Law served as French finance minister and head of the central bank. The bank printed lots of paper money, the national debt was repaid and France enjoyed brief prosperity. But inflation soon took off and crisis ensued.

The truth is that governments have an inherent bias towards inflation, especially under adverse conditions such as wars and revolutions. The Covid-19 lockdown is another such condition. Tomorrow’s inflation will alleviate some of today’s financial problems: debt levels will come down and inequalities of wealth will be mitigated. Once excessive debt has been inflated away, interest rates can return to normal. When that happens, homes should be more affordable and returns on savings will rise.

But the evils of inflation should not be overlooked. Economies do not function well when everyone is scrambling to keep pace with soaring prices. Inflations produce their own distributional pain. Workers whose incomes rise with inflation do better than retirees. Debtors will thrive at the expense of creditors. Profiteers arise, along with populists who feed on social discontents.

Modern monetary practices ensure another inflation is around the corner. MMT provides the intellectual gloss. It promises a free lunch. Even Alice shouldn’t believe that.

The writer, a financial historian, is author of a forthcoming history of interest