'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label gay. Show all posts

Showing posts with label gay. Show all posts

Saturday, 23 December 2023

Tuesday, 10 June 2014

Life without sex – it's better than you think

After I was diagnosed with a neurological condition, my partner left me and I decided to try celibacy. It has improved my friendships with women no end

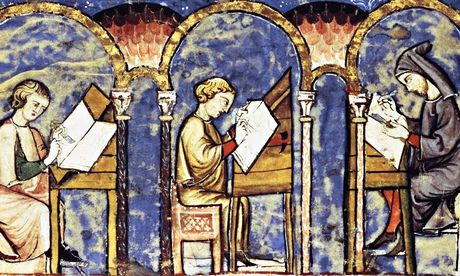

Medieval monks took vows of celibacy – but it's rare for anyone to do the same today for non-religious reasons. Photograph: Archivo Iconografico, S.A./COR

I am celibate. I am a single, heterosexual, early-middle-aged male. I have all the appendages that nature intended and, although modesty forbids that I class myself as good-looking, attractive women still make me interesting offers of intimate entanglements – and, yes, some of them are even sober at the time. (Of course, being a Guardian reader also helps to make one irresistibly attractive to the opposite sex.)

So why am I celibate? More than a decade ago I was in a relationship when I discovered that I had a neurological condition that is likely, in time (I know not when), to deteriorate. That was the end of the relationship – a decision that my partner made and which, although I took it badly at the time, I now appreciate a lot better. After all, it is one thing to think that illness or death may happen to one or other of you half a century hence, another altogether when it may be only five years down the road.

Despite this, if you met me in the street you probably wouldn't even know that there was anything wrong with me. Certainly nothing off-putting to any potential mate. So why celibacy? At first, after the break-up, I could have gone one of two ways. I could have dived head-first into a flurry of empty, hedonistic sex in a quest for revenge against all women for my ex-partner's abandonment of me. I didn't; although it crossed my mind. Instead, at first, I took some time out to grieve for the loss of a relationship that had meant a lot to me and, to be honest, to feel bloody sorry for myself.

But what to do after that? After I had spent some time in thought, both consciously and sub-consciously, I slowly came to the conclusion that celibacy was the way forward. I know within that I could live a life of permanent isolation like an anchorite, yet I know also that I would not want to. Frankly, I love women. I love their company, the sound of their voices, the way that although they occupy the same physical space as us blokes yet they seem to inhabit it so totally differently. The thought of not sharing their company was, and is, unthinkable to me. I have always preferred sex within a relationship to one-night stands. I am not a puritan, but I prefer the greater intimacy that you can achieve through a shared exploration of each other's body and desires. Yet I could not, in conscience, enter into a relationship bringing the baggage of my illness; it would not be fair to do so. Neither to a partner or, conceivably, any potential children who might inherit my illness. (Before anybody suggests seeking "relief" with a prostitute – I am a Guardian reader, we don't do that sort of thing). Such was my final decision, and it is one that I have stuck to.

Do I miss sex? Yes, but not as much as I thought that I would. Arguably, sex is an addiction. Break the cycle and, over time, the physical and psychological "need" for sex lessens – you can do without it, hard as that may be to believe. Yes, you still think about it, but over time those thoughts lose their power. I have read assiduously about the various techniques employed by monks and other religious adherents of various faiths, and the supposed benefits that they derive from abstinence. I have, however, yet to be convinced that there is any spiritual or physical gain to be had.

However, being celibate has actually improved my relationships with women – at least those that I already know (getting to know new people of the opposite sex is still no easier, although you can be seen as a "challenge" by some, which can be … interesting). Once you remove the potential for sex from the relationship, and both parties are aware of that, it changes the dynamic of the friendship. You can both be relaxed in each other's company in a way that is not possible otherwise. Daft, but seemingly true. Look, for example, at the similarly close relationships that some women have with gay men.

So would I recommend celibacy to my fellow men? I appreciate that my circumstances are not normal – and anybody finding themselves in my position would have to make up their own mind on the matter. However, people consider celibacy for many and varied reasons; so if you are considering it, I would say that it is not something to fear and can indeed be a positive choice (and, let's face it, if you try it and don't like it then you can always change your mind). Even taking a break from sex, or at least taking a break from the obsessional quest for it, can often be incredibly rewarding.

Sunday, 15 December 2013

The curious case of convenient liberalism

Swapan Dasgupta in Times of India

15 December 2013, 03:20 AM IST

Indeed, the most striking feature of the furore over the apex court judgment has been the relatively small number of voices denouncing homosexuality as ‘unnatural’ and deviant. This conservative passivity may even have conveyed an impression that India is changing socially and politically at a pace that wasn’t anticipated. Certainly, the generous overuse of ‘alternative’ to describe political euphoria and cultural impatience may even suggest that tradition has given way to post-modernity.

Yet, before urban India is equated with the bohemian quarters of New York and San Francisco, some judgmental restraint may be in order. The righteous indignation against conservative upholders of family values are not as clear cut as may seem from media reports. There are awkward questions that have been glossed over and many loose ends that have been left dangling.

A year ago, a fierce revulsion against the rape and murder of a young woman in Delhi led to Parliament amending the Penal Code and enacting a set of laws that extended the definition of rape and made punishment extremely stringent. It was the force of organized public opinion that drove the changes. Curiously, despite the Supreme Court judgment stating quite categorically that it was the responsibility of Parliament to modify section 377, there seems to be a general aversion to pressuring the law-makers to do their job and bring the criminal law system into the 21st century. Is it because India is bigoted or is there a belief that there are some issues that are best glossed over in silence?

This dichotomy of approach needs to be addressed. Conventionally, it is the job of the legislatures to write laws and for the judiciary to assess their accordance with the Constitution and to interpret them. In recent years, the judiciary has been rightly criticised for over-stepping its mark and encroaching into the domain of both the executive and the legislatures. Yet, we are in the strange situation today of the government seeking to put the onus of legitimising homosexuality on the judges.

Maybe there are larger questions involved. The battle over 377 was not between a brute majoritarianism and a minority demanding inclusion. The list of those who appealed against the Delhi High Court verdict indicates it was a contest between two minorities: religious minorities versus lifestyle minorities. Formidable organizations such as the All India Muslim Personal Law Board and some church bodies based their opposition to gay rights on theology. Liberal promoters of sexual choice on the other hand based the claim of decriminalised citizenship on modernity and scientific evidence. In short, there was a fundamental conflict between the constitutionally-protected rights of minority communities to adhere to faiths that abhor same-sex relationships and the right of gays to live by their own morals. Yet, if absolute libertarianism was to prevail, can the khap panchayats be denied their perverse moral codes?

The answer is yes but only if it is backed by majority will, expressed through Parliament. Harsh as it may sound, it is the moral majority that determines the social consensus.

There is a curious paradox here. On the question of gay rights, liberal India prefers a cosmopolitanism drawn from the contemporary West. At the same time, its endorsement of laws that are nondenominational and non-theological does not extend to support for a common civil code. Despite the Constitution’s Directive Principles, the right of every citizen to be equal before the law is deemed to be majoritarian and therefore unacceptable by the very people who stood up for inclusiveness last week.

For everything that is true of India, the opposite is turning out to be equally true.

15 December 2013, 03:20 AM IST

Last week, liberal opinion that enjoys a virtual monopoly of the airwaves pilloried the Supreme Court for what some feel was its most disgraceful judgment since the infamous Habeas Corpus case of 1976. The decision to overturn the Delhi High Court judgment taking consensual same-sex relationships outside the purview of criminal laws has been viewed as an unacceptable assault on individual freedom and minority rights and even an expression of bigotry. Overcoming fears of a virulent conservative backlash, mainstream politicians have expressed their disappointment at the judgment and happily begun using hitherto unfamiliar shorthand terms such as LGBT.

Indeed, the most striking feature of the furore over the apex court judgment has been the relatively small number of voices denouncing homosexuality as ‘unnatural’ and deviant. This conservative passivity may even have conveyed an impression that India is changing socially and politically at a pace that wasn’t anticipated. Certainly, the generous overuse of ‘alternative’ to describe political euphoria and cultural impatience may even suggest that tradition has given way to post-modernity.

Yet, before urban India is equated with the bohemian quarters of New York and San Francisco, some judgmental restraint may be in order. The righteous indignation against conservative upholders of family values are not as clear cut as may seem from media reports. There are awkward questions that have been glossed over and many loose ends that have been left dangling.

A year ago, a fierce revulsion against the rape and murder of a young woman in Delhi led to Parliament amending the Penal Code and enacting a set of laws that extended the definition of rape and made punishment extremely stringent. It was the force of organized public opinion that drove the changes. Curiously, despite the Supreme Court judgment stating quite categorically that it was the responsibility of Parliament to modify section 377, there seems to be a general aversion to pressuring the law-makers to do their job and bring the criminal law system into the 21st century. Is it because India is bigoted or is there a belief that there are some issues that are best glossed over in silence?

This dichotomy of approach needs to be addressed. Conventionally, it is the job of the legislatures to write laws and for the judiciary to assess their accordance with the Constitution and to interpret them. In recent years, the judiciary has been rightly criticised for over-stepping its mark and encroaching into the domain of both the executive and the legislatures. Yet, we are in the strange situation today of the government seeking to put the onus of legitimising homosexuality on the judges.

Maybe there are larger questions involved. The battle over 377 was not between a brute majoritarianism and a minority demanding inclusion. The list of those who appealed against the Delhi High Court verdict indicates it was a contest between two minorities: religious minorities versus lifestyle minorities. Formidable organizations such as the All India Muslim Personal Law Board and some church bodies based their opposition to gay rights on theology. Liberal promoters of sexual choice on the other hand based the claim of decriminalised citizenship on modernity and scientific evidence. In short, there was a fundamental conflict between the constitutionally-protected rights of minority communities to adhere to faiths that abhor same-sex relationships and the right of gays to live by their own morals. Yet, if absolute libertarianism was to prevail, can the khap panchayats be denied their perverse moral codes?

The answer is yes but only if it is backed by majority will, expressed through Parliament. Harsh as it may sound, it is the moral majority that determines the social consensus.

There is a curious paradox here. On the question of gay rights, liberal India prefers a cosmopolitanism drawn from the contemporary West. At the same time, its endorsement of laws that are nondenominational and non-theological does not extend to support for a common civil code. Despite the Constitution’s Directive Principles, the right of every citizen to be equal before the law is deemed to be majoritarian and therefore unacceptable by the very people who stood up for inclusiveness last week.

For everything that is true of India, the opposite is turning out to be equally true.

Friday, 13 December 2013

Why the SC’s 377 verdict is actually a boon for the gay community

Jai Anant Dehadrai in the Times of India

Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code that criminalises homosexual behaviour is an archaic and cruel remnant of our colonial past, which ought to have been struck off from the penal-code decades ago. There are no two views about this.

But the question is, struck off by whom? Let us step back and assess the facts.

The Supreme Court’s verdict has left the LGBT community agitated and deeply hurt. Their expectation was that the Court would uphold the Delhi High Court’s verdict, which held Section 377 to be unconstitutional. To their dismay, this unfortunately did not happen.

The community has waged a painfully long battle against the extreme prejudice and cruelty they face in our society. Quite admirably, this fight for respect and equal rights has always been peaceful and dignified – never marred by the mindless violence that accompanies most ‘protests’ in India. No lives were lost. No buses were burnt. No riots were reported. Even post the verdict, the community assembled peacefully at Jantar Mantar, wearing black clothes as a mark of their disappointment.

In the immediate aftermath of the judgment, social activists and civil-rights lawyers have come out in unison criticising the Supreme Court. They are of the view that this verdict has stunted their efforts to bring equal rights for the Gay community. Some have even gone on to say that this decision, in one sweeping stroke, “has taken back the fight 100 years.” Senior lawyers, who shall not be named here, have also openly questioned why the Court “missed a crucial opportunity for reforming a societal prejudice.”

But the underlying message in Justice Singhvi’s 25 page judgment appears to have been lost in the din of voices competing to denounce the verdict. Some have termed it medieval and even immoral. But absolutely no one has challenged its legality. It is absolutely crucial that we uncover this subtle truth that we’re all missing.

For a truly lasting and meaningful change, the gay and lesbian community must realise that their means must justify the righteous end they seek. Had the Supreme Court struck down the offending Section of law and played to the galleries, the victory would merely have been a pyrrhic one. The community would have lost the ethical high-ground in their quest for respect and equality.

Here is why.

Simply put, the judiciary has no business to enter into the realm of law-making or policy formulation. It is only because our elected parliamentarians have been so busy doing everything else apart from their jobs, that the Supreme Court is forced to interfere and protect the common citizen. This sad trend has become so pervasive, that now we’ve come to expect it as the norm. This is absolutely unconstitutional and against everything Ambedkar – the original champion of civil liberties, stood for and fought for. Justice Singhvi’s judgment is a loud wake-up call for the entire country – reminding us that elected representatives sitting in Parliament on tax-payers money are tasked with the responsibility and authority to make or amend laws. Relying on the Supreme Court to decide these legislative and policy matters is akin to us giving a free pass to our politicians who would rather shirk their responsibilities than take hard decisions.

The Supreme Court via this judgment has correctly shifted the spotlight onto our legislators and their shameful lethargy to evolve our legal systems. IPC 377 must certainly go – but it is the Union Executive which must rise to the occasion and effectuate this change. It is indeed shocking to hear national politicians like Rahul Gandhi criticise the Court’s order – when it is in fact the job of his government to take the initiative and scrap the law. I am surprised that we’ve blinded ourselves to this obvious political hypocrisy.

We, as Indians ought to be grateful for a judge like Justice Singhvi, who displayed staunch moral courage in the face of contrarian public sentiment to do the right thing. His reasoning does not comment on the merits of the case – which is clear as day that the law ought to be changed by legislators. The judgment of the Delhi High Court completely ignored the doctrine of separation of powers between the organs of government, which frowns upon unnecessary judicial activism by over-eager judges.

Parliament must take into account the genuine grievances of the LGBT community and not only repeal this draconic penal provision but also put into place a policy framework to protect the rights and dignity of this crucial component of our society.

Like Gandhiji said, ‘the means must justify the ends.’

Sunday, 12 May 2013

History is where the great battles of public life are now being fought

From curriculum rows to Niall Ferguson's remarks on Keynes, our past is the fuel for debate about the future

Historian Niall Ferguson: 'Part of a worryingly conservative consensus when it comes to framing our national past.' Photograph: Channel 4

The bullish Harvard historian Niall Ferguson cut an unfamiliar, almost meek figure last week. As reports of his ugly suggestion that John Maynard Keynes's homosexuality had made the great economist indifferent to the prospects of future generations surged across the blogosphere, Ferguson wisely went for a mea culpa.

So, in a cringeing piece for Harvard University's student magazine, the professor, who usually so enjoys confronting political correctness, denied he was homophobic or, indeed, racist and antisemitic for good measure.

Of course, Ferguson is none of those things. He is a brilliant financial historian, albeit with a debilitating weakness for the bon mot. But Ferguson is also part of a worryingly conservative consensus when it comes to framing our national past.

For whether it is David Starkey on Question Time, in a frenzy of misogyny and self-righteousness, denouncing Harriet Harman and Shirley Williams for being well-connected, metropolitan members of the Labour movement, or the reactionary Dominic Sandbrook using the Daily Mail to condemn with Orwellian menace any critical interpretation of Mrs Thatcher's legacy, the historical right has Britain in its grip.

And it has so at a crucial time. The rise of Ukip, combined with David Cameron's political weakness, means that, even in the absence of an official "in or out" referendum on our place in Europe, it looks like we will be debating Britain's place in the world for some years to come. And we will do against the backdrop of Michael Gove's proposed new history curriculum which, for some of its virtues, threatens to make us less, not more, confident about our internationalist standing.

For as Ferguson has discovered to his cost, history enjoys a uniquely controversial place within British public life. "There is no part of the national curriculum so likely to prove an ideological battleground for contending armies as history," complained an embattled Michael Gove in a speech last week. "There may, for all I know, be rival Whig and Marxist schools fighting a war of interpretation in chemistry or food technology but their partisans don't tend to command much column space in the broadsheets."

Even if academic historians might not like it, politicians are right to involve themselves in the curriculum debate. The importance of history in the shaping of citizenship, developing national identity and exploring the ties that bind in our increasingly disparate, multicultural society demands a democratic input. The problem is that too many of the progressive partisans we need in this struggle are missing from the field.

How different it all was 50 years ago this summer when EP Thompson published The Making of the English Working Class , his seminal account of British social history during the Industrial Revolution. "I am seeking to rescue the poor stockinger, the Luddite cropper, the 'obsolete' hand loom weaver, the 'utopian' artist ... from the condescension of posterity," he wrote.

He did so in magisterial style, providing an intimate chronicle of the brutality inflicted on the English labouring classes as Britain rose to be the workshop of the world. Thompson focused on the human stories – the Staffordshire potters, the Manchester Chartists – to build an account of an emergent, proletarian identity. It was social history as a political project, seeking to lay out all the tensions and conflict that really lie behind our island story.

As his fellow Marxist Eric Hobsbawm put it, social history was "the organisational and ideological history of the labour movement". Uncovering the lost lives and experiences of the miner and mill worker was a way of contesting power in the present. And in the wake of Thompson and Hobsbawm's histories – as well as the work of Raphael Samuel, Asa Briggs and Christopher Hill – popular interpretations of the past shifted.

In theatre, television, radio and museums, a far more vernacular and democratic account of the British past started to flourish. If, today, we are as much concerned about downstairs as upstairs, about Downton Abbey's John Bates as much as the Earl of Grantham, it is thanks to this tradition of progressive social history.

It even influenced high politics. In the flickering gloom of the 1970s' three-day week, Tony Benn retreated to the House of Commons tearoom to read radical accounts of the English civil war. "I had no idea that the Levellers had called for universal manhood suffrage, equality between the sexes and the sovereignty of the people," he confided to his diary. Benn, the semi-detached Labour cabinet minister, felt able to place himself seamlessly within this historical lineage – lamenting how "the Levellers lost and Cromwell won, and Harold Wilson or Denis Healey is the Cromwell of our day, not me".

But despite recent histories by the likes of Emma Griffin on industrialising England orEdward Vallance on radical Britain, the place of the progressive past in contemporary debate has now been abandoned. So much of the left has mired itself in the discursive dead ends of postmodernism or decided to focus its efforts abroad on the crimes of our colonial past. In their absence, we are left with Starkey and Ferguson – and BBC2 about to air yet another series on the history of the Tudor court. How much information about Anne Boleyn can modern Britain really cope with?

This narrowing of the past comes against the backdrop of ever more state school pupils being denied appropriate time for history. While studying the past is protected in prep schools, GCSE exam entries show it is under ever greater pressure in more deprived parts of the country.

Then there is the question of what students will actually be learning. Michael Gove's proposed new syllabus has rightly been criticised by historian David Cannadine and others as too prescriptive, dismissive of age-specific learning and Anglocentric. While the education secretary's foregrounding of British history is right, experts are adamant this parochial path is not the way to do it. Indeed, cynics might wonder whether Gove – the arch Eurosceptic – is already marshalling his young troops for a referendum no vote.

For whether it is the long story of Britain's place in Europe, the 1930s failings of austerity economics, the cultural history of same-sex marriage or the legacy of Thatcherism, the progressive voice in historical debate needs some rocket boosters. Niall Ferguson's crime was not just foolishly to equate Keynes's homosexuality with selfishness. Rather, it was to deny the relevance of Keynes's entire political economy – and, in the process, help to forge a governing consensus that is proving disastrous for British living standards.

That is what we need an apology for.

Friday, 7 December 2012

Sex tips for writers

‘Bad sex' writing is funny because the anatomical vocabulary of conventional sex writing is hackneyed, impossible to visualise, stale, and given to bragging.

I started ruminating about sex writing while thinking about the annual Bad Sex awards – won this year by the novelist Nancy Huston for Infrared. Most sex writing is either soft-focus romance, (like those fuzzy movies you can rent in hotel rooms), utterly elided ("they read no more that night ... ") or hardcore one-handed reading, designed more as a substitute for sex than a realistic description of sex, which is usually comic, following Henri Bergson's definition of comedy as something that occurs when the body fails the spirit. Of course "bad sex" writing is funny because the anatomical vocabulary of conventional sex writing is hackneyed, impossible to visualise because full of ludicrously mixed metaphors, stale, and given to bragging.

Years ago Renaud Camus wrote a book called Tricks, which astonished everyone because he was determined to record his fiascos as often as his triumphs. (Today some people don't even know what the word "tricks" means).

Everyone seems agreed that writing about sex is perilous, partly because it threatens to swamp highly individualised characters in a generic, featureless activity (much like coffee-cup dialogue, during which everyone sounds the same), and partly because it feels ... tacky. Even careful writers begin to sound like porn soundtracks when they turn to sex writing.

As Susan Sontag once observed, pornography is practical. It was designed as a marital aid, and its vocabulary should follow natural biological rhythms and stick with hot-button words in order to produce a predictable climax. It is not about sex but is sex. Whereas the great sex writers (Harold Brodkey, DH Lawrence, Robert Gluck, David Plante, the Australian Frank Moorhouse) have a quirky, phenomenological, realistic approach to sex. They are doing what the Russian formalists said was the secret of all good fiction – making the familiar strange, writing from the Martian's point of view.

I've written some of the strangest pages anyone's typed out about sex. In my first novel, Forgetting Elena, an amnesiac man is drawn into sex by the Elena of the title. Only he doesn't remember of course what sex is, and he veers from thinking it's a coded form of communication to imagining it's a way of inflicting pain mixed with pleasure on oneself and on one's partner. I suppose I was basing it on my own first experiences of sex as a sub-teen. In another obscure novel, Caracole, I have lots of heterosexual sex, which is written from the point of view of a virginal teenage boy.

To be sure, most of my sex writing has involved two teen males or two (or more) adult men. I always bear in mind Harold Brodkey's remark to me that if you write "she went down on him", it is a "lie", because no one can summarise an intense, prolonged and inevitably unrepeatable and original sex act with a snappy five-word formula like that. He felt that every sex act had to be entirely rethought and reimagined from the beginning to the end. Which of course made his sex writing very, very long.

I've always thought that the main problem with gay erotica is what I call "the cock-and-balls" problem. It seems to me that gay sex writing is a major test for the typical reader, who is a middle-aged woman. Isn't it terribly alienating to have to read about those rigid shafts and hairy bums?

I guess straight men would hate such lurid passages just as much if they read fiction. But older women, at least, often like sex to be linked to sentiment and never to be purely anatomical. I imagine that's why so few gay novels have "broken through" to the general public; all their sexual hydraulics must seem either bleak or seedy. Or "boring", as middle-class people say when they're shocked.

Years ago Renaud Camus wrote a book called Tricks, which astonished everyone because he was determined to record his fiascos as often as his triumphs. (Today some people don't even know what the word "tricks" means).

Everyone seems agreed that writing about sex is perilous, partly because it threatens to swamp highly individualised characters in a generic, featureless activity (much like coffee-cup dialogue, during which everyone sounds the same), and partly because it feels ... tacky. Even careful writers begin to sound like porn soundtracks when they turn to sex writing.

As Susan Sontag once observed, pornography is practical. It was designed as a marital aid, and its vocabulary should follow natural biological rhythms and stick with hot-button words in order to produce a predictable climax. It is not about sex but is sex. Whereas the great sex writers (Harold Brodkey, DH Lawrence, Robert Gluck, David Plante, the Australian Frank Moorhouse) have a quirky, phenomenological, realistic approach to sex. They are doing what the Russian formalists said was the secret of all good fiction – making the familiar strange, writing from the Martian's point of view.

I've written some of the strangest pages anyone's typed out about sex. In my first novel, Forgetting Elena, an amnesiac man is drawn into sex by the Elena of the title. Only he doesn't remember of course what sex is, and he veers from thinking it's a coded form of communication to imagining it's a way of inflicting pain mixed with pleasure on oneself and on one's partner. I suppose I was basing it on my own first experiences of sex as a sub-teen. In another obscure novel, Caracole, I have lots of heterosexual sex, which is written from the point of view of a virginal teenage boy.

To be sure, most of my sex writing has involved two teen males or two (or more) adult men. I always bear in mind Harold Brodkey's remark to me that if you write "she went down on him", it is a "lie", because no one can summarise an intense, prolonged and inevitably unrepeatable and original sex act with a snappy five-word formula like that. He felt that every sex act had to be entirely rethought and reimagined from the beginning to the end. Which of course made his sex writing very, very long.

I've always thought that the main problem with gay erotica is what I call "the cock-and-balls" problem. It seems to me that gay sex writing is a major test for the typical reader, who is a middle-aged woman. Isn't it terribly alienating to have to read about those rigid shafts and hairy bums?

I guess straight men would hate such lurid passages just as much if they read fiction. But older women, at least, often like sex to be linked to sentiment and never to be purely anatomical. I imagine that's why so few gay novels have "broken through" to the general public; all their sexual hydraulics must seem either bleak or seedy. Or "boring", as middle-class people say when they're shocked.

Thursday, 29 November 2012

Parkinson's sufferer wins six figure payout from GlaxoSmithKline over drug that turned him into a 'gay sex and gambling addict'

A French appeals court has upheld a ruling ordering GlaxoSmithKline to pay €197,000 (£159,000) to a man who claimed a drug given to him to treat Parkinson's turned him into a 'gay sex addict'.

Didier Jambart, 52, was prescribed the drug Requip in 2003 to treat his illness.

Within two years of beginning to take the drug the married father-of-two says he developed an uncontrollable passion for gay sex and gambling - at one point even selling his children's toys to fund his addiction.

He was awarded £160,000 in damages after a court in Rennes, France, upheld his claims.

The ruling, which is considered ground-breaking, was made yesterday by the appeal court, which awarded damages to Mr Jambart.

Following the decision Mr Jambart appeared outside the court with his wife Christine beside him.

Jambart broke down in tears as judges upheld his claim that his life had become 'hell' after he started taking Requip, a drug made by GSK.

Mr Jambart began taking the drug for Parkinson's in 2003, he had formerly worked as a well-respected bank manager and local councillor, and is a father of two.

In total Mr Jambert said he gambled away 82,000 euros, mostly through internet betting on horse races. He also said he engaged in frantic searches for gay sex.

He started exhibiting himself on websites and arranging encounters, one of which he claimed resulted in him being raped.

He said his family had not understood what was going on at first.

Mr Jambert said he realised the drug was responsible when he stumbled across a website that made a connection between the drug and addictions in 2005. When he stopped the drug he claims his behaviour returned to normal.

"It's a great day," he said. "It's been a seven-year battle with our limited means for recognition of the fact that GSK lied to us and shattered our lives."

He added: 'I am happy that justice has been done. I am happy for my wife and my children. I am at last going to be able to sleep at night and profit from life. '

He added that the money awarded would, 'never replace the years of pain.'

The court heard that Requip's side-effects had been made public in 2006, but had reportedly been known for years.

Mr Jambert said that GSK patients should have been informed earlier.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)