US tech innovators have a culture of regarding government as an innovation-blocking nuisance. But when Silicon Valley Bank collapsed, investors screamed for state protection writes John Naughton in The Guardian

So one day Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) was a bank, and then the next day it was a smoking hulk that looked as though it might bring down a whole segment of the US banking sector. The US government, which is widely regarded by the denizens of Silicon Valley as a lumbering, obsolescent colossus, then magically turned on a dime, ensuring that no depositors would lose even a cent. And over on this side of the pond, regulators arranged that HSBC, another lumbering colossus, would buy the UK subsidiary of SVB for the princely sum of £1.

Panic over, then? We’ll see. In the meantime it’s worth taking a more sardonic look at what went on.

The first thing to understand is that “Silicon Valley” is actually a reality-distortion field inhabited by people who inhale their own fumes and believe they’re living through Renaissance 2.0, with Palo Alto as the new Florence. The prevailing religion is founder worship, and its elders live on Sand Hill Road in San Francisco and are called venture capitalists. These elders decide who is to be elevated to the privileged caste of “founders”.

To achieve this status it is necessary to a) be male; b) have a Big Idea for disrupting something; and c) never have knowingly worn a suit and tie. Once admitted to the priesthood, the elders arrange for a large tipper-truck loaded with $100 bills to arrive at the new member’s door and cover his driveway with cash.

But this presents the new founder with a problem: where to store the loot while he is getting on with the business of disruption? Enter stage left one Gregory Becker, CEO of SVB and famous in the valley for being worshipful of founders and slavishly attentive to their needs. His company would keep their cash safe, help them manage their personal wealth, borrow against their private stock holdings and occasionally even give them mortgages for those $15m dream houses on which they had set what might loosely be called their hearts.

The most striking takeaway was the evidence produced by the crisis of the arrant stupidity of some of those involved

So SVB was awash with money. But, as programmers say, that was a bug not a feature. Traditionally, as Bloomberg’s Matt Levine points out, “the way a bank works is that it takes deposits from people who have money, and makes loans to people who need money”. SVB’s problem was that mostly its customers didn’t need loans. So the bank had all this customer cash and needed to do something with it. Its solution was not to give loans to risky corporate borrowers, but to buy long-dated, ostensibly safe securities like Treasury bonds. So 75% of SVB’s debt portfolio – nominally worth $95bn (£80bn) – was in those “held to maturity” assets. On average, other banks with at least $1bn in assets classified only 6% of their debt in this category at the end of 2022.

There was, however, one fly in this ointment. As every schoolboy (and girl) knows, when interest rates go up, the market value of long-term bonds goes down. And the US Federal Reserve had been raising interest rates to combat inflation. Suddenly, SVB’s long-term hedge started to look like a millstone. Moody’s, the rating agency, noticed and Mr Becker began frantically to search for a solution. Word got out – as word always does – and the elders on Sand Hill Road began to whisper to their esteemed founder proteges that they should pull their deposits out, and the next day they obediently withdrew $42bn. The rest, as they say, is recent history.

What can we infer about the culture of Silicon Valley from this shambles? Well, first up is its pervasive hypocrisy. Palo Alto is the centre of a microculture that regards the state as an innovation-blocking nuisance. But the minute the security of bank deposits greater than the $250,000 limit was in doubt, the screams for state protection were deafening. (In the end, the deposits were protected – by a state agency.) And when people started wondering why SVB wasn’t subjected to the “stress testing” imposed on big banks after the 2008 crash, we discovered that some of the most prominent lobbyists against such measures being applied to SVB-size institutions included that company’s own executives. What came to mind at that point was Samuel Johnson’s observation that “the loudest yelps for liberty” were invariably heard from the drivers of slaves.

But the most striking takeaway of all was the evidence produced by the crisis of the arrant stupidity of some of those involved. The venture capitalists whose whispered advice to their proteges triggered the fatal run must have known what the consequences would be. And how could a bank whose solvency hinged on assumptions about the value of long-term bonds be taken by surprise by the impact of interest-rate increases? All that was needed to model the risk was an intern with a spreadsheet. But apparently no such intern was available. Perhaps s/he was at Stanford doing a thesis on the Renaissance.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label libertarian. Show all posts

Showing posts with label libertarian. Show all posts

Sunday, 19 March 2023

Saturday, 18 March 2023

Sunday, 18 December 2022

Why were the media hypnotised by Sam Bankman-Fried?

John Naughton in The Guardian

So Sam Bankman-Fried (henceforth SBF) was eventually arrested at his multimillion-dollar residence in the Bahamas, a tax haven with nice beaches attached. The only mystery about this was the unconscionable length of time that it took the Bahamian authorities to measure him for handcuffs. The police said that he was arrested at the request of US legal authorities for “financial offences” under US and Bahamian laws connected with the FTX cryptocurrency exchange that he co-founded in 2019 and Alameda Research, a hedge fund that he set up in 2017. On Tuesday, a local court denied him bail, which suggests that an extradition request from the US will be granted and he will soon be appearing in a New York courtroom.

The grisly details of what SBF is alleged to be guilty of will emerge in forthcoming criminal proceedings. But already expectations are high: Amazon has announced that it is working on a series about the scandal in partnership with the Russo brothers, the makers of Marvel movies.

For the moment, though, a brief outline will have to do. FTX was a cryptocurrency exchange that provided an easy way for people to buy and sell these virtual currencies. Many people had invested billions of “real” money in it to facilitate their participation in the crypto casino. But in early November, rumours of problems with FTX surfaced after Binance, another crypto exchange, dramatically refused to bail it out, citing “corporate due diligence” and reports of “mishandled customer funds”.

There then followed, as the night the day, a run on FTX, as panicking investors tried to withdraw their money, which in turn led to its insolvency and a filing for bankruptcy. The big puzzle, though, was why couldn’t FTX have just given its investors their money back? The answer appears to be that it wasn’t there; in some way, SBF’s hedge fund had been treating FTX as its piggy bank, possibly even playing the hedge fund market with investors’ money.

The thought SBF might be as manipulative as any oil mogul or tobacco executive never occurred to the poor dears

Once it was clear that this particular game was up, SBF then embarked on an astonishing apology tour on every media outlet he could find. In almost every interview he was touchingly apologetic while at the same time maintaining that he had no knowledge of potentially fraudulent activities at his own company, including using billions of dollars of customers’ deposits as collateral for loans for other purposes. He had, he explained ruefully, been out of his depth. On some occasions, he also seemed to be trying to deflect blame on to Caroline Ellison, the former CEO of his other company, Alameda Research.

The biggest question prompted by this apology tour is: why did so many apparently serious media outfits let him get away with it? The interview questions were often softball ones, occasionally toe-curlingly so. Some interviewers confessed apologetically that they knew nothing about the complex businesses he had run and allowed themselves to be bemused by the incomprehensible bullshit he was emitting. Often, they seemed hypnotised, as many otherwise sensible people had been before the crash, by this tech wunderkind with big hair and baggy shorts who had, until recently, been promising to give away his phenomenal wealth to good causes, while in fact he had seemingly been presiding over the vaporisation of billions of dollars of other people’s savings.

But this embarrassing failure of mainstream media was really just the encore to an even bigger failure – their wilful blindness to what had been going on while SBF was in his prime. It turned out that earlier in the year the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) had written to FTX seeking to determine if the company was as flaky as some observers (mainly on the web) had suspected. As Cory Doctorow pointed out, the SEC never got an answer, because eight US lawmakers – four Republicans and four Democrats – wrote a letter to the SEC chairman demanding that he back off. And five of these eight, according to Doctorow, had received substantial case donations from SBF, his employees, affiliated businesses or political action committees.

There was a real story here, in other words, long before FTX imploded. But it wasn’t told because the mainstream media were so invested in the founder-worship that is the curse of the tech industry, not to mention some of those who cover it. The thought that “the poster child for the libertarian ethos that crypto profits accrued to those most capable”, as one commentator described SBF, might be as politically manipulative as any oil mogul or tobacco executive never occurred to the poor dears. Sometimes, societies get the mainstream media they deserve.

So Sam Bankman-Fried (henceforth SBF) was eventually arrested at his multimillion-dollar residence in the Bahamas, a tax haven with nice beaches attached. The only mystery about this was the unconscionable length of time that it took the Bahamian authorities to measure him for handcuffs. The police said that he was arrested at the request of US legal authorities for “financial offences” under US and Bahamian laws connected with the FTX cryptocurrency exchange that he co-founded in 2019 and Alameda Research, a hedge fund that he set up in 2017. On Tuesday, a local court denied him bail, which suggests that an extradition request from the US will be granted and he will soon be appearing in a New York courtroom.

The grisly details of what SBF is alleged to be guilty of will emerge in forthcoming criminal proceedings. But already expectations are high: Amazon has announced that it is working on a series about the scandal in partnership with the Russo brothers, the makers of Marvel movies.

For the moment, though, a brief outline will have to do. FTX was a cryptocurrency exchange that provided an easy way for people to buy and sell these virtual currencies. Many people had invested billions of “real” money in it to facilitate their participation in the crypto casino. But in early November, rumours of problems with FTX surfaced after Binance, another crypto exchange, dramatically refused to bail it out, citing “corporate due diligence” and reports of “mishandled customer funds”.

There then followed, as the night the day, a run on FTX, as panicking investors tried to withdraw their money, which in turn led to its insolvency and a filing for bankruptcy. The big puzzle, though, was why couldn’t FTX have just given its investors their money back? The answer appears to be that it wasn’t there; in some way, SBF’s hedge fund had been treating FTX as its piggy bank, possibly even playing the hedge fund market with investors’ money.

The thought SBF might be as manipulative as any oil mogul or tobacco executive never occurred to the poor dears

Once it was clear that this particular game was up, SBF then embarked on an astonishing apology tour on every media outlet he could find. In almost every interview he was touchingly apologetic while at the same time maintaining that he had no knowledge of potentially fraudulent activities at his own company, including using billions of dollars of customers’ deposits as collateral for loans for other purposes. He had, he explained ruefully, been out of his depth. On some occasions, he also seemed to be trying to deflect blame on to Caroline Ellison, the former CEO of his other company, Alameda Research.

The biggest question prompted by this apology tour is: why did so many apparently serious media outfits let him get away with it? The interview questions were often softball ones, occasionally toe-curlingly so. Some interviewers confessed apologetically that they knew nothing about the complex businesses he had run and allowed themselves to be bemused by the incomprehensible bullshit he was emitting. Often, they seemed hypnotised, as many otherwise sensible people had been before the crash, by this tech wunderkind with big hair and baggy shorts who had, until recently, been promising to give away his phenomenal wealth to good causes, while in fact he had seemingly been presiding over the vaporisation of billions of dollars of other people’s savings.

But this embarrassing failure of mainstream media was really just the encore to an even bigger failure – their wilful blindness to what had been going on while SBF was in his prime. It turned out that earlier in the year the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) had written to FTX seeking to determine if the company was as flaky as some observers (mainly on the web) had suspected. As Cory Doctorow pointed out, the SEC never got an answer, because eight US lawmakers – four Republicans and four Democrats – wrote a letter to the SEC chairman demanding that he back off. And five of these eight, according to Doctorow, had received substantial case donations from SBF, his employees, affiliated businesses or political action committees.

There was a real story here, in other words, long before FTX imploded. But it wasn’t told because the mainstream media were so invested in the founder-worship that is the curse of the tech industry, not to mention some of those who cover it. The thought that “the poster child for the libertarian ethos that crypto profits accrued to those most capable”, as one commentator described SBF, might be as politically manipulative as any oil mogul or tobacco executive never occurred to the poor dears. Sometimes, societies get the mainstream media they deserve.

Friday, 26 March 2021

Saturday, 9 May 2020

Free markets must be protected through the pandemic

The Financial Times Editorial Board

Short of a communist revolution, it is hard to imagine how governments could have intervened in private markets — for labour, for credit, for the exchange of goods and services — as quickly and deeply as in the past two months of lockdowns. Overnight, millions of private sector employees have been getting their pay cheques from public budgets and central banks have flooded financial markets with electronic money.

One may be forgiven for worrying that the pandemic has brought socialism on its coat-tails. Yet the paradox is that today’s emergency measures are necessary to protect the long-term health of free markets and a capitalist economy. Those who, like this news organisation, value those institutions must welcome this unprecedented intervention.

Liberal democratic capitalism, with free and open markets and secure private property rights, remains the best institutional framework to meet the aspiration of freedom and prosperity for all. But liberal democratic capitalism is not self-sufficient, and needs to be protected and maintained to be resilient.

Catastrophic emergencies — wars, pandemics and natural disasters — bring risks that only governments can protect against. A purist libertarianism that denies people this protection cannot survive its first crisis.

Capitalism can also undermine itself over time, if it is not tended by smart regulatory frameworks. The global financial crisis — caused in part by opacity, self-dealing and perverse incentives — showed that markets need good rules of the road to remain free, open and efficient. The accelerating disruptions from climate change prove a similar point.

Like all social systems, free markets depend on political legitimacy. One of the greatest long-term threats to capitalism functioning well is the perception, let alone the reality, that markets which are supposed to be free are actually rigged in favour of the powerful.

A creeping suspicion this might be the case had started to erode its popular support, especially after the financial crisis. The rising wave of young self-confessed socialists in the US and UK, homelands of economic liberalism, was clear proof of that. Mismanaged economies that leave many people behind give fuel to left-wing populists, who see state intervention as a replacement for capitalism, not just a corrective. But they also empower right-wing populists, who offer business a Faustian bargain of collaboration.

Today’s situation resembles that of the 1930s. Back then, centrist liberals from US president Franklin Delano Roosevelt to British economist John Maynard Keynes saw that liberal democratic capitalism, in order to survive, had to be shown to work for everyone. The victory of their ideas set the stage for the success of western capitalism in the decades after the second world war.

Now, like then, capitalism does not need replacement even if it may need repair. Free markets work best when all have access to them, which requires the state to provide smart, transparent and proportionate ground rules and offer social insurance in the last resort. The latter is exactly what governments have done in the necessary battle against Covid-19. Their many support measures, costly as they are, constitute an investment into a safe return of freer markets and a self-sustaining capitalism when the crisis abates.

The task for friends of liberal capitalism is to determine how free-market values can be buttressed in the future. That is a task made easier, not harder, if the state does its job well today.

Short of a communist revolution, it is hard to imagine how governments could have intervened in private markets — for labour, for credit, for the exchange of goods and services — as quickly and deeply as in the past two months of lockdowns. Overnight, millions of private sector employees have been getting their pay cheques from public budgets and central banks have flooded financial markets with electronic money.

One may be forgiven for worrying that the pandemic has brought socialism on its coat-tails. Yet the paradox is that today’s emergency measures are necessary to protect the long-term health of free markets and a capitalist economy. Those who, like this news organisation, value those institutions must welcome this unprecedented intervention.

Liberal democratic capitalism, with free and open markets and secure private property rights, remains the best institutional framework to meet the aspiration of freedom and prosperity for all. But liberal democratic capitalism is not self-sufficient, and needs to be protected and maintained to be resilient.

Catastrophic emergencies — wars, pandemics and natural disasters — bring risks that only governments can protect against. A purist libertarianism that denies people this protection cannot survive its first crisis.

Capitalism can also undermine itself over time, if it is not tended by smart regulatory frameworks. The global financial crisis — caused in part by opacity, self-dealing and perverse incentives — showed that markets need good rules of the road to remain free, open and efficient. The accelerating disruptions from climate change prove a similar point.

Like all social systems, free markets depend on political legitimacy. One of the greatest long-term threats to capitalism functioning well is the perception, let alone the reality, that markets which are supposed to be free are actually rigged in favour of the powerful.

A creeping suspicion this might be the case had started to erode its popular support, especially after the financial crisis. The rising wave of young self-confessed socialists in the US and UK, homelands of economic liberalism, was clear proof of that. Mismanaged economies that leave many people behind give fuel to left-wing populists, who see state intervention as a replacement for capitalism, not just a corrective. But they also empower right-wing populists, who offer business a Faustian bargain of collaboration.

Today’s situation resembles that of the 1930s. Back then, centrist liberals from US president Franklin Delano Roosevelt to British economist John Maynard Keynes saw that liberal democratic capitalism, in order to survive, had to be shown to work for everyone. The victory of their ideas set the stage for the success of western capitalism in the decades after the second world war.

Now, like then, capitalism does not need replacement even if it may need repair. Free markets work best when all have access to them, which requires the state to provide smart, transparent and proportionate ground rules and offer social insurance in the last resort. The latter is exactly what governments have done in the necessary battle against Covid-19. Their many support measures, costly as they are, constitute an investment into a safe return of freer markets and a self-sustaining capitalism when the crisis abates.

The task for friends of liberal capitalism is to determine how free-market values can be buttressed in the future. That is a task made easier, not harder, if the state does its job well today.

Thursday, 8 October 2015

Money isn’t restricted by borders, so why are people?

Giles Fraser in The Guardian

Theresa May won’t be around in the early 22nd century when, according to Star Trek at least, Dr Emory Erickson will have invented the transporter – a device that will be able to dematerialise a person into an energy pattern, beam them to another place or planet, and then rematerialise them back again. In such a world people will be able to move as quickly and freely as an email.

The philosopher Derek Parfit has rightly questioned whether such a thing is even philosophically possible: will the rematerialised person be the same person as the dematerialised one, or just a perfect copy. (What would happen if two copies of me were rematerialised? Would they both be me?) Parfit thus raises a fascinating philosophical question about what we mean by personal identity – or what makes me me.

But, just for the sake of argument, imagine what such a device would do to Mrs May’s keep-them-all-out immigration policy. With the transporter, there could be no border controls and no restrictions on the free movement of individuals. Economic migrants would love it. People will be able to live and work where they like, beaming instantly from Syria to Sussex or indeed to Saturn. And because of this, the whole concept of the nation state will eventually wither away. People will have become more powerful than the state.

Fanciful? Of course. Forget about the technical problems. The fundamental problem is that human beings are not fungible. A copy is not the same as its original. A person cannot be dematerialised into a series of digital zeros and ones, get beamed over space and be rematerialised as the same person.

But – and here is the really big thing – money can be. For the whole point about money is that it is fungible. It can be converted into zeros and ones and it can be digitally shot across space. And since the late 1970s, when capital controls were relaxed all around the world, and then even more so since the digital revolution, money has been able to go where it pleases, unimpeded, without any need for a passport or reference to border control. Every day, trillions of dollars are economic migrants, crossing boundaries as if they didn’t exist, pouring in and out of countries looking for the most economically advantageous place to be. And, just as with the fanciful people-transporter example, this free movement of capital is how the nation state is dissolving.

This week the OECD published a report on international companies and tax avoidance. Big companies like AstraZeneca are able to pay next to no tax in the UK because they just transport their profits to a low-tax regime in another country. Indeed, some countries, pathetically prostrating themselves before the gods of finance, exist for little other than this purpose. And so the situation we find ourselves in is that money is free to travel as it pleases but people are not. We have got used to this as the new normal, and it largely goes unremarked. Yes, there are a few on the libertarian fringe who recognise this as a contradiction and argue that people should be as free as capital. But the majority on the right do everything they can to protect the free movement of capital and restrict the free movement of people.

Which is why the neoliberal right in Britain has utterly contradictory instincts over Europe – they want the free trade bit but they don’t want the free people bit. And they scare us with how the free movement of people threatens our national identity but refuse to face the fact that the free movement of capital can be seen as doing exactly the same. They talk a good game about the importance of freedom: but it’s one rule for capital and another for people.

Of course the transporter won’t happen. But with the internet, the imagination can travel where it will. And that means poor people will always see and want what rich people have. And not even Mrs May will be able to stop them crossing dangerous seas and borders to find it.

Theresa May won’t be around in the early 22nd century when, according to Star Trek at least, Dr Emory Erickson will have invented the transporter – a device that will be able to dematerialise a person into an energy pattern, beam them to another place or planet, and then rematerialise them back again. In such a world people will be able to move as quickly and freely as an email.

The philosopher Derek Parfit has rightly questioned whether such a thing is even philosophically possible: will the rematerialised person be the same person as the dematerialised one, or just a perfect copy. (What would happen if two copies of me were rematerialised? Would they both be me?) Parfit thus raises a fascinating philosophical question about what we mean by personal identity – or what makes me me.

But, just for the sake of argument, imagine what such a device would do to Mrs May’s keep-them-all-out immigration policy. With the transporter, there could be no border controls and no restrictions on the free movement of individuals. Economic migrants would love it. People will be able to live and work where they like, beaming instantly from Syria to Sussex or indeed to Saturn. And because of this, the whole concept of the nation state will eventually wither away. People will have become more powerful than the state.

Fanciful? Of course. Forget about the technical problems. The fundamental problem is that human beings are not fungible. A copy is not the same as its original. A person cannot be dematerialised into a series of digital zeros and ones, get beamed over space and be rematerialised as the same person.

But – and here is the really big thing – money can be. For the whole point about money is that it is fungible. It can be converted into zeros and ones and it can be digitally shot across space. And since the late 1970s, when capital controls were relaxed all around the world, and then even more so since the digital revolution, money has been able to go where it pleases, unimpeded, without any need for a passport or reference to border control. Every day, trillions of dollars are economic migrants, crossing boundaries as if they didn’t exist, pouring in and out of countries looking for the most economically advantageous place to be. And, just as with the fanciful people-transporter example, this free movement of capital is how the nation state is dissolving.

This week the OECD published a report on international companies and tax avoidance. Big companies like AstraZeneca are able to pay next to no tax in the UK because they just transport their profits to a low-tax regime in another country. Indeed, some countries, pathetically prostrating themselves before the gods of finance, exist for little other than this purpose. And so the situation we find ourselves in is that money is free to travel as it pleases but people are not. We have got used to this as the new normal, and it largely goes unremarked. Yes, there are a few on the libertarian fringe who recognise this as a contradiction and argue that people should be as free as capital. But the majority on the right do everything they can to protect the free movement of capital and restrict the free movement of people.

Which is why the neoliberal right in Britain has utterly contradictory instincts over Europe – they want the free trade bit but they don’t want the free people bit. And they scare us with how the free movement of people threatens our national identity but refuse to face the fact that the free movement of capital can be seen as doing exactly the same. They talk a good game about the importance of freedom: but it’s one rule for capital and another for people.

Of course the transporter won’t happen. But with the internet, the imagination can travel where it will. And that means poor people will always see and want what rich people have. And not even Mrs May will be able to stop them crossing dangerous seas and borders to find it.

Sunday, 7 December 2014

Forget austerity – what we need is a stronger state and more taxation

The income tax system needs reshaping. This is not easy. But nor is reducing the state to its smallest level for 80 years

If the Conservative party forms the next government, by 2020 the state will probably be the smallest it has been – in relation to GDP – for 80 years. So declared the Office for Budget Responsibility last Wednesday, in the wake of the autumn statement. By 2020, spending per head of population will have fallen by around a third in 10 years. In some areas – in our cities and our criminal justice system – the reductions will be even more draconian. This is the most dramatic change in state capability that any British government has ever engineered.

The chancellor may complain about the “hyperbolic” tone of some BBC reporting. But surely only in a one-party state would this dramatic plan not be discussed in appropriately dramatic terms. Britain is to become the site of a massive experiment in economic and social libertarianism whose authors have never fessed up to the sheer audacity and scale of what they are doing. They have just dumbly insisted there is no alternative. The autumn statement was the moment the implications became clear.

A financial crisis has been allowed to morph into a crisis of public provision because the government of the day will not lift a finger to compensate for the haemorrhaging of the UK tax base. What the state does is not the subject of a collective decision with concerned weighing of options. Instead, it’s an afterthought, with the greater priorities a reduction in public borrowing and freezing or lowering tax rates.

All the state can spend is what is left after those two greater priorities are met, and if it has to shrink to pre-modern levels then so be it. The market will provide: charity will alleviate suffering; people will get by; the roof will not fall in. Lifting taxation can never be considered to close the gap. It is, it is alleged, both economically self-defeating and immoral.

A cool £54bn has gone missing since 2010. Then the government projected that in 2014/15 its total tax revenues would be £700bn. In fact, they will be £646bn, according to the OBR. Public spending, on the other hand, has behaved almost exactly as forecast. In 2010, the government projected that its spending would be £738bn in this financial year. The Treasury is to be congratulated on its capacities as national book-keeper in chief. The actual figure is £737bn, an accuracy I doubt many private companies could reproduce – or even individual readers of the Observer. It is not runaway public spending that is causing borrowing to stay stubbornly high, thus triggering the extreme shrinkage of the state: it is the hollowing out of the tax base.

There are three principal causes. The first is that the structure of the economic recovery is delivering a reduced tax yield. There are too many low-paying jobs and pay on average is stagnating, so that aggregate income tax revenues are growing much less rapidly than in previous recoveries. We are drinking and smoking less, so there is less revenue from alcohol and tobacco duties. Altogether this accounts for around a third of the shortfall.

Another third is a result of the chancellor wanting to show his tax-cutting credentials as a true Thatcherite man: he has cut corporate tax rates, frozen the business rate, not adjusted council tax bands upwards, not increased petrol duties, lowered the top rate of tax and increased personal allowances. The last element is down to our living with an epidemic of tax avoidance and evasion, as the last G20 summit recognised – and which even Osborne says he deplores. Too many companies and rich individuals are gaming the system.

Put all this together and Britain has lost that £54bn. But matters are made worse by the interaction of Britain’s highly centralised Treasury and a chancellor with Osborne’s instincts. Giles Wilkes, former adviser to Vince Cable, and Stian Westlake, research director at Nesta, write in an important paper, The End of the Treasury, that the Treasury inverts the way that spending and taxing decisions should be made. It starts with a target for borrowing, not differentiating great capital projects such as London’s Crossrail from spending on the NHS. Then it projects tax revenues assuming no changes, and sets aside money for fixed obligations, such as pensions.

Finally, departments fight over the left-overs on a year by year basis, with the Treasury policing spending with a ferocious rigidity. The benefit is that it can control spending to the last billion. The cost is that there is never a weighing up of the benefits of raising taxes against a particular use for public spending, nor any strategic long-term programme of investment.

This is bad enough in ordinary times, but when a chancellor refuses to consider raising taxes as the tax base collapses it is a recipe for disaster. It results in a minimal state, with implications for prisons, schools, courts, policing, legal aid, care, security and defence that are profound. Some of this could be avoided if, as both Labour and the LibDems propose, capital investment was not lumped in with current spending so that virtuous borrowing could be separated out. The country may also get lucky: wages stop stagnating and income tax receipts rise.

But the bigger truth is that if Britain wants the scale of public activity congruent with a civilised society, it has to be paid for. The reaction will be hysterical, but lifting taxes by 3% of GDP to 38.5% to find the missing £54bn will still leave Britain below the crucial 40% benchmark, thus undertaxed by comparison with most advanced countries. The whole system of property taxation needs overhauling. The VAT base can be broadened. Environmental taxes can be extended. Osborne’s proposals to ensure companies pay tax on UK revenues need to be tougher and introduced earlier. The income tax system needs reshaping.

None of this is easy. But neither is reducing the state to its smallest level for 80 years. Reducing spending on schools further is surely short changing our children. How much smaller should the army, navy and air force become? Is the welfare system to return to a system of discretionary poor relief? Do we share the libertarian view that the state is worthless – and there is no co-dependency between public and private? What role do we want the state to have in our civilisation? The right would have it that none of these questions can be asked because all involve an increase in taxation: our only future is a 1930s scale state.

There is a different future, and our politicians of the centre and left have to argue for it, but they must accept it has to be paid for. This has become an existential divide. Politics and political argument have never mattered more.

Sunday, 15 December 2013

The curious case of convenient liberalism

Swapan Dasgupta in Times of India

15 December 2013, 03:20 AM IST

Indeed, the most striking feature of the furore over the apex court judgment has been the relatively small number of voices denouncing homosexuality as ‘unnatural’ and deviant. This conservative passivity may even have conveyed an impression that India is changing socially and politically at a pace that wasn’t anticipated. Certainly, the generous overuse of ‘alternative’ to describe political euphoria and cultural impatience may even suggest that tradition has given way to post-modernity.

Yet, before urban India is equated with the bohemian quarters of New York and San Francisco, some judgmental restraint may be in order. The righteous indignation against conservative upholders of family values are not as clear cut as may seem from media reports. There are awkward questions that have been glossed over and many loose ends that have been left dangling.

A year ago, a fierce revulsion against the rape and murder of a young woman in Delhi led to Parliament amending the Penal Code and enacting a set of laws that extended the definition of rape and made punishment extremely stringent. It was the force of organized public opinion that drove the changes. Curiously, despite the Supreme Court judgment stating quite categorically that it was the responsibility of Parliament to modify section 377, there seems to be a general aversion to pressuring the law-makers to do their job and bring the criminal law system into the 21st century. Is it because India is bigoted or is there a belief that there are some issues that are best glossed over in silence?

This dichotomy of approach needs to be addressed. Conventionally, it is the job of the legislatures to write laws and for the judiciary to assess their accordance with the Constitution and to interpret them. In recent years, the judiciary has been rightly criticised for over-stepping its mark and encroaching into the domain of both the executive and the legislatures. Yet, we are in the strange situation today of the government seeking to put the onus of legitimising homosexuality on the judges.

Maybe there are larger questions involved. The battle over 377 was not between a brute majoritarianism and a minority demanding inclusion. The list of those who appealed against the Delhi High Court verdict indicates it was a contest between two minorities: religious minorities versus lifestyle minorities. Formidable organizations such as the All India Muslim Personal Law Board and some church bodies based their opposition to gay rights on theology. Liberal promoters of sexual choice on the other hand based the claim of decriminalised citizenship on modernity and scientific evidence. In short, there was a fundamental conflict between the constitutionally-protected rights of minority communities to adhere to faiths that abhor same-sex relationships and the right of gays to live by their own morals. Yet, if absolute libertarianism was to prevail, can the khap panchayats be denied their perverse moral codes?

The answer is yes but only if it is backed by majority will, expressed through Parliament. Harsh as it may sound, it is the moral majority that determines the social consensus.

There is a curious paradox here. On the question of gay rights, liberal India prefers a cosmopolitanism drawn from the contemporary West. At the same time, its endorsement of laws that are nondenominational and non-theological does not extend to support for a common civil code. Despite the Constitution’s Directive Principles, the right of every citizen to be equal before the law is deemed to be majoritarian and therefore unacceptable by the very people who stood up for inclusiveness last week.

For everything that is true of India, the opposite is turning out to be equally true.

15 December 2013, 03:20 AM IST

Last week, liberal opinion that enjoys a virtual monopoly of the airwaves pilloried the Supreme Court for what some feel was its most disgraceful judgment since the infamous Habeas Corpus case of 1976. The decision to overturn the Delhi High Court judgment taking consensual same-sex relationships outside the purview of criminal laws has been viewed as an unacceptable assault on individual freedom and minority rights and even an expression of bigotry. Overcoming fears of a virulent conservative backlash, mainstream politicians have expressed their disappointment at the judgment and happily begun using hitherto unfamiliar shorthand terms such as LGBT.

Indeed, the most striking feature of the furore over the apex court judgment has been the relatively small number of voices denouncing homosexuality as ‘unnatural’ and deviant. This conservative passivity may even have conveyed an impression that India is changing socially and politically at a pace that wasn’t anticipated. Certainly, the generous overuse of ‘alternative’ to describe political euphoria and cultural impatience may even suggest that tradition has given way to post-modernity.

Yet, before urban India is equated with the bohemian quarters of New York and San Francisco, some judgmental restraint may be in order. The righteous indignation against conservative upholders of family values are not as clear cut as may seem from media reports. There are awkward questions that have been glossed over and many loose ends that have been left dangling.

A year ago, a fierce revulsion against the rape and murder of a young woman in Delhi led to Parliament amending the Penal Code and enacting a set of laws that extended the definition of rape and made punishment extremely stringent. It was the force of organized public opinion that drove the changes. Curiously, despite the Supreme Court judgment stating quite categorically that it was the responsibility of Parliament to modify section 377, there seems to be a general aversion to pressuring the law-makers to do their job and bring the criminal law system into the 21st century. Is it because India is bigoted or is there a belief that there are some issues that are best glossed over in silence?

This dichotomy of approach needs to be addressed. Conventionally, it is the job of the legislatures to write laws and for the judiciary to assess their accordance with the Constitution and to interpret them. In recent years, the judiciary has been rightly criticised for over-stepping its mark and encroaching into the domain of both the executive and the legislatures. Yet, we are in the strange situation today of the government seeking to put the onus of legitimising homosexuality on the judges.

Maybe there are larger questions involved. The battle over 377 was not between a brute majoritarianism and a minority demanding inclusion. The list of those who appealed against the Delhi High Court verdict indicates it was a contest between two minorities: religious minorities versus lifestyle minorities. Formidable organizations such as the All India Muslim Personal Law Board and some church bodies based their opposition to gay rights on theology. Liberal promoters of sexual choice on the other hand based the claim of decriminalised citizenship on modernity and scientific evidence. In short, there was a fundamental conflict between the constitutionally-protected rights of minority communities to adhere to faiths that abhor same-sex relationships and the right of gays to live by their own morals. Yet, if absolute libertarianism was to prevail, can the khap panchayats be denied their perverse moral codes?

The answer is yes but only if it is backed by majority will, expressed through Parliament. Harsh as it may sound, it is the moral majority that determines the social consensus.

There is a curious paradox here. On the question of gay rights, liberal India prefers a cosmopolitanism drawn from the contemporary West. At the same time, its endorsement of laws that are nondenominational and non-theological does not extend to support for a common civil code. Despite the Constitution’s Directive Principles, the right of every citizen to be equal before the law is deemed to be majoritarian and therefore unacceptable by the very people who stood up for inclusiveness last week.

For everything that is true of India, the opposite is turning out to be equally true.

Monday, 7 October 2013

Ed Miliband isn’t offering socialism – but the Tories are still terrified

Owen Jones in The Independent

The rule of capital is “unimpaired and virtually unchallenged; no social democratic party is nowadays concerned to mount a serious challenge to that rule.” If he was still with us, the socialist Ralph Miliband would have noted two big changes since he wrote these words not long before his death in 1994. Firstly, he’d observe – with little surprise – that capitalism has plunged itself into yet another almighty mess. Secondly, he would undoubtedly be consumed with pride that his youngest son had assumed the leadership of one of these social democratic parties. Momentous events indeed: but his wistful conclusion would have remained the same.

That in mind, I wonder what Ralph Miliband would have made of his son’s transformation from a “laughable blank sheet of paper” to “frothing-at-the-mouth Communist who is going to nationalise your mother quicker than you can say ‘Friedrich Engels had a cracking beard'”. Ed Miliband’s suggested crackdown on land-banking (once endorsed by Boris “Commie” Johnson) and a temporary freeze on energy prices (backed by arch-Leninist Tom Burke, the former Tory special adviser on energy) have provoked comparisons with undesirable elements ranging from Robert Mugabe to the Bolsheviks. After he stood on a soapbox in Brighton and indulged a bystander asking when he would “bring back socialism”, the British right have behaved as though Labour are planning to finish what Lenin was doing before he was so rudely interrupted.

In part, it is the sinister red-baiting of Ed Miliband through his dead father, culminating with the Daily Mail accusing the Labour leader of planning to drive “a hammer and sickle through the heart of the nation so many of us love”. Pass the spliff, Mr Dacre. “Like a good Marxist,” writes The Daily Telegraph’s Charles Moore, “he detects the cowardice latent in capitalists,” accusing Miliband of being “part of an ideology” which is “ultimately pauperising and totalitarian.” Jeremy Hunt odiously endorsed the Mail’s lunacy, arguing that “Ralph Miliband was no friend of the free market and I have never heard Ed Miliband say he supports it.” George Osborne, meanwhile, accuses Ed Miliband of making “essentially the same argument Karl Marx made in Das Kapital.”

This is what is really going on. The right are so drunk on three decades of free-market triumphalism, so used to the left being smashed and battered, that they believe even the mildest deviation from the neo-liberal script is unacceptable. They thought all of these battles had been won, that they were rid of all their turbulent priests, and now they are incandescent at the alleged resurgence of defeated enemies. Don’t you know you’re supposed to be dead? It’s not even the most moderate form of social democracy that the right are trying to drive from political life. Anyone who does not advocate yet more aggressive doses of neo-liberalism – more privatisation, more cuts to the taxes of the wealthy, more attacks on workers’ rights – is liable to come under suspicion, too.

The British right’s strategy is pretty clear. They want to do to “socialist” what the US right have done to “liberal”: turn it into an unequivocally toxic word that no-one in public life would want to associate with, and use it as a means to smear political opponents deemed to deviate from Britain’s suffocating neo-liberal consensus. Bemusing, to say the least, given Labour first officially declared itself a “democratic socialist party” under Tony Blair in 1995 as a sop to the left in the party’s new revised Clause IV. He even wrote a Fabian Society pamphlet entitled Socialism. Yes, granted it meant nothing more to him than motherhood and apple pie, and he had more leeway than Miliband because it was rather more difficult to pin him down as a heartfelt lefty, but the point is even New Labour could happily bandy “socialism” about.

But let’s get a bit of perspective here. Socialism? I don’t think so. Labour have – wrongly – committed themselves to Osborne’s spending plans in the first year of a new government. As Michael Gove gobbles up the comprehensive education system for dinner, Labour’s response has been, to say the least, muted. Medialand may be wailing about 1970s socialism being back with a vengeance, but given polls show 69 per cent want the energy companies nationalised, the Labour leader still found himself to the right of public opinion. No commitment on rail renationalisation, either, which some polls show is even the preferred option of Tory voters. There’s suggestions Labour would hike the top rate of tax up to 50 per cent again, but polls show the public would be happy to take it to 60 per cent. Not exactly the full-scale expropriation of the bourgeoisie, is it?

In truth, Ed Miliband strikes me as an old-style social democrat, perhaps what would have been described as the “Old Labour Right” before Blair’s Year Zero. He generally seems well-intentioned about dragging the political centre of gravity away from the Thatcherite right, but appears to fear a lack of political space to do so. He has made moves towards a mild social democracy in limited areas – but it is just that, mild, although even that is too strong for those now imitating the hysterical rhetoric of Barack Obama’s Tea Party opponents.

It is difficult, sometimes, not to be overwhelmed by the hypocrisy of the right. They don’t mind a bit of statism, as long as, generally speaking, it’s propping up the wealthy. Banks bailed out by the taxpayer, not free-market dogma; infrastructure, education, and research and development that all businesses depend on, paid for by the state; private contractors who owe their profits solely to state largesse; even mortgages now underwritten by the state. It is only when it is suggested that the state might help those near the bottom of the pile that the right cries foul. In their world, “moderation” means the biggest cuts since the 1920s, the driving of over a million children into poverty, privatising the NHS without public consent and dropping bombs on foreign countries. “Extremism” is curbing energy prices, asking the booming wealthy to pay a bit more tax, and stopping construction firms squatting on land during a housing crisis. So let’s start telling it as it is: they are the extremists, however much they squeal disingenuously about the “centre ground”.

Real democratic socialism would not mean the odd curb on energy prices. It would mean a living wage instead of subsidises for poverty pay, and allowing councils to build housing rather than taxpayers lining the pockets of private landlords. It would mean arguing for social ownership – from banks to the railways – giving real democratic control to workers and consumers.

That is not currently on offer from Labour. But the right fear that, if even mild social-democratic populism proves popular, the door might open to more radical ideas. Their whole Thatcherite consensus could prove imperilled. And that is why the British right are starting to sound like bad-tempered Joseph McCarthy clones who stigmatise even timid social democracy as dangerous extremism to block any further shift away from free market extremism. But a word of warning to the right. Look across the Atlantic. How has the Tea Party-isation of the US right worked out for them? Because that is exactly where you are heading.

Obamacare begins – and the right is terrified that it will work

Rupert Cornwell in The Independent

In a week in which all the talk was of shutdown, the most notable development here in Washington was something that opened up. I refer to the launch of the online federal and state health exchanges that are a key feature of Obamacare, allowing those without health insurance to shop around for the best plan.

Readers who have managed to keep up with the latest antics of what passes as the United States Congress will be aware that the reason Republican hardliners shut down the government was to force the President to delay – or to put it less politely, dismantle – his signature legislative achievement. Yet in a splendid two-finger gesture by fate, on the very day that veterans' services, national parks and a host of other government functions were closing, the health exchanges, symbol of everything those Republicans detest about Obamacare, were opening for business.

True, the moment was pretty shambolic. Overwhelmed by visitors, the websites virtually seized up on day one, though things seemed to improve slightly as the week wore on. But it was a start, and let it never be forgotten what Obamacare is attempting: to bring the US in line with every other advanced industrial country and provide healthcare for all its citizens, irrespective of their means.

Others had tried it before. Harry Truman called for universal health insurance in the late 1940s, only to be described by Republican adversaries as a crypto-communist. Two decades later, Lyndon Johnson did push through Medicare and Medicaid for elderly and poor Americans. Not, however, before a certain aspiring conservative politician named Ronald Reagan predicted that Medicare would see Americans "spending their sunset years telling our children and our children's children what it was like when men were free".

Then came Bill Clinton. Alas, he created the impression that a coterie of White House officials, led by his wife, Hillary, was trying to foist its pet ideas upon a suspicious country and he, too, failed. But in 2010, after a monumental fight, Obama's plan was finally approved by Congress.

Yet still Republicans continue their Canute-like refusal to accept the rules of democracy. No matter that the measure was signed by the President and ratified by the Supreme Court, or that Republicans resoundingly lost the 2012 presidential election in which Obamacare was a prime issue. The law, their leaders say, is a "monstrosity," a "trainwreck" that must be fought by every means, even if that means closing down the government.

Now, no one would argue that the reform is perfect. Even without the distortions and abuse peddled by the right- and left-wing media alike, it is extremely hard to understand. Nor will it cover absolutely everyone. If you started from scratch, you would almost certainly go for some form of single-payer system, a universal, government-funded scheme of the sort that Truman advocated.

Determined not to make the Clintons' mistake, Obama consulted with every interested party: Democrats and Republicans, hospitals, private insurers, doctors and the pharmaceutical companies. He bent over backwards to retain the existing structure of employer-based coverage, even dropping proposals for a "public option" favoured by the left as a way of keeping the private insurers honest. In doing so, he bowed, in effect, to the conservatives' argument that an alternative state-run insurance scheme would pave the way for a single-payer system.

But, as Obama has painfully discovered, offer Republicans an olive branch and they'll use it to whip you. Since 2010, the Republican-controlled House has passed no fewer than 42 resolutions seeking to overturn Obamacare (albeit knowing that the Senate would reject every one.) Now it has shut down the government, even though 70 per cent of the US public disapproves of the tactic, and even right-wing commentators argue that the way to get rid of Obamacare is via the ballot box, not blackmail. Elect a Republican president and a Republican Congress, they say, then repeal the thing.

At state level, where Republicans dominate, the sabotage of Obamacare is endless. Many states have failed to set up health exchanges. Citizens are being urged to flout the law and pay a fine rather than obey the individual mandate that requires them to buy insurance. Most inexcusable of all, a swathe of red states is refusing to expand Medicaid, which helps the poor. That will be critical for the success of Obamacare – even though the federal government is picking up 100 per cent of the cost for the first three years, and 90 per cent thereafter.

Why this scorched-earth opposition? After all, the mandate was originally a Republican idea, put forward by the impeccably conservative Heritage Foundation some two decades ago. Obamacare, moreover, is based on the healthcare reform enacted in Massachusetts in 2006 under the state's then governor, Mitt Romney – the Republicans' White House candidate in 2012. And at a simple human level, why oppose a law providing cover for 28 million people who don't have it?

One reason is Republicans' visceral dislike of Obama, on political, personal or racist grounds – or a blend of all three. Ideologically, they are terrified not that healthcare reform will fail, with the dire consequences they predict, but that it will succeed.

Success would strike at the very core of Republican belief, that government is bad for you and should be reduced to the bare minimum to sustain a functioning state. Despite public wariness of the law as a whole, several of its main provisions are extremely popular (as the once reviled Medicare now is.) If Obamacare works, Americans would feel better about government in general; the terrible monster erected by Republican demonology would be seen to be benign, after all. What price the party's electoral prospects then?

Sunday, 6 October 2013

How I bought drugs from 'dark net' – it's just like Amazon run by cartels

Last week the FBI arrested Dread Pirate Roberts, founder of Silk Road, a site on the 'dark net' where visitors could buy drugs at the click of a mouse. Though Dread – aka Ross Ulbricht – earned millions, was he really driven by America's anti-state libertarian philosophy?

The FBI alleges Ross Ulbricht ran the vast underground drug marketplace Silk Road for more than two years. Photograph: theguardian.com

Dear FBI agents, my name is Carole Cadwalladr and in February this year I was asked to investigate the so-called "dark net" for a feature in this newspaper. I downloaded Tor on to my computer, the anonymous browser developed by the US navy, Googled "Silk Roaddrugs" and then cut and pasted this link http://silkroadvb5piz3r.onion/ into the address field.

And bingo! There it was: Silk Road, the site, which until the FBI closed it down on Thursday and arrested a 29-year-old American in San Francisco, was the web's most notorious marketplace.

The "dark net" or the "deep web", the hidden part of the internet invisible to Google, might sound like a murky, inaccessible underworld but the reality is that it's right there, a click away, at the end of your mouse. It took me about 10 minutes of Googling and downloading to find and access the site on that February morning, and yet arriving at the home page of Silk Road was like stumbling into a parallel universe, a universe where eBay had been taken over by international drug cartels and Amazon offers a choice of books, DVDS and hallucinogens.

Drugs are just another market, and on Silk Road it was a market laid bare, differentiated by price, quality, point of origin, supposed effects and lavish user reviews. There were categories for "cannabis", "dissociatives", "ecstasy", "opioids", "prescription", "psychedelics", "stimulants" and, my favourite, "precursors". (If you've watched Breaking Bad, you'll know that's the stuff you need to make certain drugs and which Walt has to hold up trains and rob factories to find. Or, had he known about Silk Road, clicked a link on his browser.)

And, just like eBay, there were star ratings for sellers, detailed feedback, customer service assurances, an escrow system and a busy forum in which users posted helpful tips. I looked on the UK cannabis forum, which had 30,000 postings, and a vendor called JesusOfRave was recommended. He had 100% feedback, promised "stealth" packaging and boasted excellent customer reviews: "The level of customer care you go to often makes me forget that this is an illegal drug market," said one.

JesusOfRave boasted on his profile: "Working with UK distributors, importers and producers to source quality, we run a tight ship and aim to get your order out same or next day. This tight ship also refers to our attitude to your and our privacy. We have been doing this for a long time … been playing with encryption since 0BC and rebelling against the State for just as long."

And so, federal agents, though I'm sure you know this already, not least because the Guardian revealed on Friday that the National Security Agency (NSA) and GCHQ have successfully cracked Tor on occasion, I ordered "1g of Manali Charras [cannabis] (free UK delivery)", costing 1.16 bitcoins (the cryptocurrency then worth around £15). I used a false name with my own address, and two days later an envelope arrived at my door with an address in Bethnal Green Road, east London, on the return label and a small vacuum-packed package inside: a small lump of dope.

It's still sitting in its original envelope in the drawer of my desk. I got a bit stumped with my dark net story, put it on hold and became more interested in the wonderful world of cryptocurrencies as the value of bitcoins soared over the next few months (the 1.5 bitcoins I'd bought for £20 were worth £300 at one point this spring).

Just under a month ago I was intrigued to see that Forbes magazine had managed to get an interview with "Dread Pirate Roberts", the site's administrator. And then, last week, came the news that Dread Pirate Roberts was 29-year-old Ross Ulbricht, a University of Texas physics graduate who, according to the FBI's documents, had not just run the site – which it alleges earned him $80m in commission – but had hired a contract killer for $80,000 to rub out an employee who had tried to blackmail him.

If that sounds far-fetched, papers filed last Thursday show that he tried to take a contract on a second person. The documents showed that the FBI had access to Silk Road's servers from July, and that the contract killer Ulbricht had thought he'd hired was a federal agent. It's an astonishing, preposterous end to what was an astonishing, preposterous site, though the papers show that while the crime might have been hi-tech, cracking it was a matter of old-fashioned, painstaking detective work.

Except, of course, that it's not the end of it. There are two other similar websites already up and running – Sheep and Black Market Reloaded – which have both seen a dramatic uplift in users in the last few days, and others will surely follow. Because what Silk Road did for drugs was what eBay did for secondhand goods, and Airbnb has done for accommodation: it created a viable trust system that benefited both buyers and sellers.

Nicholas Christin, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, who conducted six months of research into the site, said that what surprised him most was how "normal" it was. "To me, the most surprising thing was how normal, when you set aside the goods being sold, the whole market appears to be," he said. And, while many people would be alarmed at the prospect of their teenagers buying drugs online, Silk Road was a whole lot more professional, regulated and controlled than buying drugs offline.

What's apparent from Dread Pirate Roberts's interview with Forbes and comments he made on the site's forum is that the motivation behind the site does not seem to have been making money (though clearly it did: an estimated $1.2bn), or a belief that drugs hold the key to some sort of mystical self-fulfillment, but that the state has no right to interfere in the lives of individuals. One of the details that enabled the FBI to track Ulbricht was the fact that he "favourited" several clips from the Ludwig von Mises Institute, a libertarian Alabama-based thinktank devoted to furthering what is known as the Austrian school of economics. Years later, Dread Pirate Roberts would cite the same theory on Silk Road's forum.

"What we're doing isn't about scoring drugs or 'sticking it to the man'," said Dread Pirate Roberts in the Forbes interview. "It's about standing up for our rights as human beings and refusing to submit when we've done no wrong."

And it's this that is possibly the most interesting aspect of the story. Because, while Edward Snowden's and the Guardian's revelations about the NSA have shown how all-encompassing the state's surveillance has become, a counterculture movement of digital activists espousing the importance of freedom, individualism and the right to a private life beyond the state's control is also rapidly gaining traction.

It's the philosophy behind innovations as diverse as the 3D printed gun and sites as mainstream as PayPal, and its proponents are young, computer-savvy idealists with the digital skills to invent new ways of circumventing the encroaching power of the state.

Ulbricht certainly doesn't seem to have been living the life you imagine of a criminal overlord. He lived in a shared apartment. If he had millions stashed away somewhere, he certainly doesn't seem to have been spending it on high-performance cars and penthouses.

His LinkedIn page, while possibly not the best arena for self-expression for a man being hunted by the FBI, demonstrates that his beliefs are grounded in libertarian ideology: "I want to use economic theory as a means to abolish the use of coercion and aggression amongst mankind," he wrote. "The most widespread and systemic use of force is amongst institutions and governments … the best way to change a government is to change the minds of the governed … to that end, I am creating an economic simulation to give people a firsthand experience of what it would be like to live in a world without the systemic use of force."

Silk Road, it turns out, might have been that world. Anybody who has seen All the President's Men knows that, when it comes to criminality, the answer has always been to "follow the money". But in the age of bitcoin, that's of a different order of difficulty. Silk Road is just one website; bitcoin is potentially the foundation for a whole new economic order.

Tuesday, 16 July 2013

Cigarette packaging: the corporate smokescreen

Noble sentiments about individual liberty are being used to bend democracy to the will of the tobacco industry

BETA

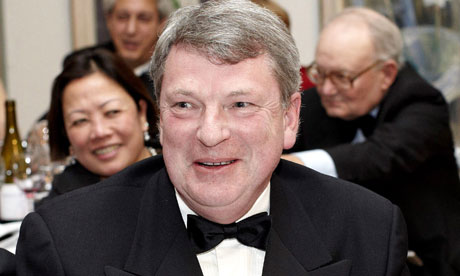

'Lynton Crosby personifies the new dispensation, in which men and women glide between corporations and politics, and appear to act as agents for big business within government.' Photograph: David Hartley / Rex Features

It's a victory for the hidden persuaders, the astroturfers, sock puppets, purchased scholars and corporate moles. On Friday the government announced that it will not oblige tobacco companies to sell cigarettes in plain packaging. How did it happen? The public was overwhelmingly in favour. The evidence that plain packets will discourage young people from smoking is powerful. But it fell victim to a lobbying campaign that was anything but plainly packaged.

Tobacco companies are not allowed to advertise their products. Nor, as they are so unpopular, can they appeal directly to the public. So they spend their cash on astroturfing(fake grassroots campaigns) and front groups. There is plenty of money to be made by people unscrupulous enough to take it.

Much of the anger about this decision has been focused on Lynton Crosby. Crosby is David Cameron's election co-ordinator. He also runs a lobbying company that works for the cigarette firms Philip Morris and British American Tobacco. He personifies the new dispensation, in which men and women glide between corporations and politics, and appear to act as agents for big business within government. The purpose of today's technocratic politics is to make democracy safe for corporations: to go through the motions of democratic consent while reshaping the nation at their behest.

But even if Crosby is sacked, the infrastructure of hidden persuasion will remain intact. Nor will it be affected by the register of lobbyists that David Cameron will announce on Tuesday, antiquated before it is launched.

Nanny state, health police, red tape, big government: these terms have been devised or popularised by corporate front groups. The companies who fund them are often ones that cause serious harm to human welfare. The front groups campaign not only against specific regulations, but also against the very principle of the democratic restraint of business.

I see the "free market thinktanks" as the most useful of these groups. Their purpose, I believe, is to invest corporate lobbying with authority. Mark Littlewood, the head of one of these thinktanks – the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) – has described plain packaging as "the latest ludicrous move in the unending, ceaseless, bullying war against those who choose to produce and consume tobacco". Over the past few days he's been in the media repeatedly, railing against the policy. So do the IEA's obsessions just happen to coincide with those of the cigarette firms? The IEA refuses to say who its sponsors are and how much they pay. But as a result of persistent digging, we now know that British American Tobacco, Philip Morris and Japan Tobacco International have been funding the institute – in BAT's case since 1963. British American Tobacco has admitted that it gave the institute £20,000 last year and that it's "planning to increase our contribution in 2013 and 2014".

Otherwise it's a void. The IEA tells me, "We do not accept any earmarked money for commissioned research work from any company." Really? But whether companies pay for specific publications or whether they continue to fund a body that – by the purest serendipity – publishes books and pamphlets that concur with the desires of its sponsors, surely makes no difference.

The institute has almost unrivalled access to the BBC and other media, where it promotes the corporate agenda without ever being asked to disclose its interests. Because they remain hidden, it retains a credibility its corporate funders lack. Amazingly, since 2011 Mark Littlewood has also been the government's adviser on cutting the regulations that business doesn't like. Corporate conflicts of interest intrude into the heart of this country's political life.

In 2002, a letter sent by the philosopher Roger Scruton to Japan Tobacco International (which manufactures Camel, Winston and Silk Cut) was leaked. In the letter, Professor Scruton complained that the £4,500 a month JTI was secretly paying him to place pro-tobacco articles in newspapers was insufficient: could they please raise it to £5,500?

Scruton was also working for the Institute of Economic Affairs, through which he published a major report attacking the World Health Organisation for trying to regulate tobacco. When his secret sponsorship was revealed, the IEA pronounced itself shocked: shocked to find that tobacco funding is going on in here. It claimed that "in the past we have relied on our authors to come forward with any competing interests, but that is going to change ... we are developing a policy to ensure it doesn't happen again." Oh yes? Eleven years later I have yet to find a declaration in any IEA publication that the institute (let alone the author) has been taking money from companies with an interest in its contents.

The IEA is one of several groups that appear to be used as a political battering ram by tobacco companies. On the TobaccoTactics website you can find similarly gruesome details about the financial interests and lobbying activities of, for example, the Adam Smith Institute and the Common Sense Alliance.

Even where tobacco funding is acknowledged, only half the story is told. Forest, a group that admits that "most of our money is donated by UK-based tobacco companies", has spawned a campaign against plain packaging called Hands Off Our Packs. The Department of Health has published some remarkable documents, alleging the blatant rigging of signatures on a petition launched by this campaign. Hands Off Our Packs is run by Angela Harbutt. She lives with Mark Littlewood.

Libertarianism in the hands of these people is a racket. All those noble sentiments about individual liberty, limited government and economic freedom are nothing but a smokescreen, a disguised form of corporate advertising. Whether Mark Littlewood, Lynton Crosby or David Cameron articulate it, it means the same thing: ideological cover for the corporations and the very rich.

Arguing against plain packaging on the Today programme, Mark Field MP, who came across as the transcendental form of an amoral, bumbling Tory twit, recited the usual tobacco company talking points, with their usual disingenuous disclaimers. In doing so, he made a magnificent slip of the tongue. "We don't want to encourage young people to take up advertising ... er, er, to take up tobacco smoking." He got it right the first time.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)