'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label people. Show all posts

Showing posts with label people. Show all posts

Sunday, 3 March 2024

Sunday, 7 January 2024

Thursday, 4 January 2024

Wednesday, 14 June 2023

Thursday, 8 June 2023

McCarthyism rises in Labour as it readies for power

Having examined how the North of Tyne mayor was barred from standing again, I see something akin to McCarthyism writes Aditya Chakrabortty in The Guardian

I first met the man who has been all over this week’s political headlines four years ago, 300 miles up the A1 from Westminster. It was a bitterly cold Saturday morning in the Northumberland coastal town of Newbiggin and Jamie Driscoll was asking for votes. He’d just caused a minor political earthquake by winning Labour members’ support to run for the new position of mayor of North of Tyne. The cert for that role had been Nick Forbes, Newcastle council leader and longtime big beast – not Driscoll, who had been a local councillor for a few months and who, on winning the selection, had had to rush out to buy his only suit.

I watched this stubbly, scruffy, upbeat outsider doorknock around an estate of small houses and exotic garden statuettes, to a reaction chillier than the wind whipping in from the North Sea. For decades, this had been Labour country, where that political tradition ran through the local economy, its institutions and people’s very identities. But over the past 50 years all that had been destroyed and now it was the land of Vote Leave, desolate and nihilistic. If residents spoke to canvassers at all, it was to spit out statements like “I don’t follow politics”.

After more slammed doors, one activist sighed: “Policy doesn’t matter here. They’ve forgotten what government can do.” For all Driscoll’s ideas and energy, I wrote at the time, his biggest challenge would be closing the vast gulf between the governed and their governors.

That tableau has come to mind many times since the Labour party barred Driscoll from standing for re-election. No more will he trigger democratic earthquakes. Instead, he has become fodder for lobby journalists. When I met him in Newcastle this week, he was slaloming between interviews for Radio 4, ITV, national newspapers, Newsnight and more. The ending of his political career has done more for his national profile than four years in office. I listened as each outlet demanded its shot of Westminster caffeine. Hardly anyone asked what it meant for the north-east, for local democracy, for the people in Newbiggin and anyone else who long ago tuned out all politicians as fraudulent liars only in it for themselves.

And why wouldn’t they? I have chased down and sifted through evidence, much of it never revealed before, and it points to a stitch-up bigger than anything on the Great Sewing Bee. The jumped-up outsider, Driscoll, has been tossed in the bin – but he is merely collateral damage in a one-sided Labour factional fight, whose actors appear not to give a damn for people’s reputations or for the public they’re meant to serve.

Let’s work backwards. Labour officials blocked Driscoll last Friday, soon after he’d been interviewed by a panel drawn largely from the party’s national executive committee. The email he received reads: “[T]he NEC panel has determined that you will not be progressing further as a candidate in this process.” But while the party gave no official reason to the candidate, its enforcers were happy to brief lobby journalists – who in turn quoted anonymous sources that it was because in March he had appeared at a Newcastle theatre with Ken Loach to discuss his films. The renowned director had been expelled as a Labour member in 2021.

I first met the man who has been all over this week’s political headlines four years ago, 300 miles up the A1 from Westminster. It was a bitterly cold Saturday morning in the Northumberland coastal town of Newbiggin and Jamie Driscoll was asking for votes. He’d just caused a minor political earthquake by winning Labour members’ support to run for the new position of mayor of North of Tyne. The cert for that role had been Nick Forbes, Newcastle council leader and longtime big beast – not Driscoll, who had been a local councillor for a few months and who, on winning the selection, had had to rush out to buy his only suit.

I watched this stubbly, scruffy, upbeat outsider doorknock around an estate of small houses and exotic garden statuettes, to a reaction chillier than the wind whipping in from the North Sea. For decades, this had been Labour country, where that political tradition ran through the local economy, its institutions and people’s very identities. But over the past 50 years all that had been destroyed and now it was the land of Vote Leave, desolate and nihilistic. If residents spoke to canvassers at all, it was to spit out statements like “I don’t follow politics”.

After more slammed doors, one activist sighed: “Policy doesn’t matter here. They’ve forgotten what government can do.” For all Driscoll’s ideas and energy, I wrote at the time, his biggest challenge would be closing the vast gulf between the governed and their governors.

That tableau has come to mind many times since the Labour party barred Driscoll from standing for re-election. No more will he trigger democratic earthquakes. Instead, he has become fodder for lobby journalists. When I met him in Newcastle this week, he was slaloming between interviews for Radio 4, ITV, national newspapers, Newsnight and more. The ending of his political career has done more for his national profile than four years in office. I listened as each outlet demanded its shot of Westminster caffeine. Hardly anyone asked what it meant for the north-east, for local democracy, for the people in Newbiggin and anyone else who long ago tuned out all politicians as fraudulent liars only in it for themselves.

And why wouldn’t they? I have chased down and sifted through evidence, much of it never revealed before, and it points to a stitch-up bigger than anything on the Great Sewing Bee. The jumped-up outsider, Driscoll, has been tossed in the bin – but he is merely collateral damage in a one-sided Labour factional fight, whose actors appear not to give a damn for people’s reputations or for the public they’re meant to serve.

Let’s work backwards. Labour officials blocked Driscoll last Friday, soon after he’d been interviewed by a panel drawn largely from the party’s national executive committee. The email he received reads: “[T]he NEC panel has determined that you will not be progressing further as a candidate in this process.” But while the party gave no official reason to the candidate, its enforcers were happy to brief lobby journalists – who in turn quoted anonymous sources that it was because in March he had appeared at a Newcastle theatre with Ken Loach to discuss his films. The renowned director had been expelled as a Labour member in 2021.

Jamie Driscoll addresses the Transport for the North conference in March. Photograph: Ian Forsyth/Getty Images

On Sunday, Labour frontbencher Jonathan Reynolds told Sky News that Driscoll was excluded for sharing a platform with “someone who themselves has been expelled for their views on antisemitism” – a line swiftly amplified by the media, yet not quite true. I asked Loach’s office to forward his letters of expulsion, which say only that he is “ineligible” due to his support of “a political organisation other than an official Labour group”. That was Labour Against the Witchhunt, which did claim allegations of Labour antisemitism were “politically motivated”. Reynolds was conflating the two. I asked how many other journalists had sought clarification. The answer was one.

A column about Driscoll is not the place to litigate Ken Loach’s views, even if I disagree with much of what he says about Labour’s treatment of antisemitism. It barely needs saying that sitting on stage with a director to discuss their films does not mean you share all their opinions. Far more troubling for British democracy is how anonymous, factional briefings are simply machine-pressed into newspaper “facts” then spewed out on TV.

“They were always looking to get me,” Driscoll claimed this week. I have read emails dating back to 2020 where the new metro mayor asks Labour officials for the party’s local membership lists used by councillors, MPs and mayors as standard. But not here: IT issues meant the lists supposedly weren’t shareable. Until this year that is, when he was told the upcoming mayoral contest meant he could only access lists “if you make a confirmation that you are not seeking the selection”. Another email, sent by Driscoll last month to party officials, notes that a local constituency party has been told by a senior official to disinvite him from speaking.

Asked for comment, Labour didn’t reply – but this is petty, attritional stuff, which is what happens when politics is evacuated of ideas and arguments and becomes simply about who is in whose good books. Cliqueishness is hardly exclusive to Keir Starmer’s Labour, but it is starker now because instead of real politics all this lot have is office politics.

Which brings us back to the much-discussed NEC panel, supposedly to divine his suitability to stand. I have viewed footage of the entire hour on Zoom, which discusses nothing of Driscoll’s beliefs or achievements. Three of the five panel members are from groups on the right of the party, and all anyone wants to know is why he spoke to Loach. They refer to the director’s “controversial views” and quote the Jewish Chronicle’s coverage. How, they ask, might the event be viewed by a “hostile media”?

Driscoll replies that Holocaust denial is “abhorrent” and that he has signed up to the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s definition of antisemitism. He recalls how he used to fight fascists in the street. None of it is good enough.

A rather bumptious young man informs the mayor that “you can’t separate someone’s views from their work”. The twentysomething declares that Driscoll shouldn’t have discussed the films but instead attacked Loach’s politics. On that basis, Starmer ought to be disqualified for appearing with Loach on the BBC’s Question Time – and so too should the shadow foreign secretary, David Lammy, who in 2019 wrote a paean in this paper to Loach’s Sorry We Missed You, praising the way it “brings across how the right to a family life has been eroded in modern Britain”.

We all know that a week is a long time in Starmer’s politics, but he did once proclaim a proud regionalism. Now what’s left?

Attacking McCarthyism, Ed Murrow told his TV audience: “We must not confuse dissent with disloyalty. We must remember always that accusation is not proof and that conviction depends upon evidence and due process of law. We will not walk in fear, one of another.”

By these standards, Driscoll is a victim of McCarthyism. The office he holds is now a mere electoral toy to be enjoyed by a favoured faction. And those people in Newbiggin and Ashington and anyone else who might be looking on with half an eye will see nothing but machine politicians serving themselves. This was the swamp out of which Nigel Farage emerged.

On Sunday, Labour frontbencher Jonathan Reynolds told Sky News that Driscoll was excluded for sharing a platform with “someone who themselves has been expelled for their views on antisemitism” – a line swiftly amplified by the media, yet not quite true. I asked Loach’s office to forward his letters of expulsion, which say only that he is “ineligible” due to his support of “a political organisation other than an official Labour group”. That was Labour Against the Witchhunt, which did claim allegations of Labour antisemitism were “politically motivated”. Reynolds was conflating the two. I asked how many other journalists had sought clarification. The answer was one.

A column about Driscoll is not the place to litigate Ken Loach’s views, even if I disagree with much of what he says about Labour’s treatment of antisemitism. It barely needs saying that sitting on stage with a director to discuss their films does not mean you share all their opinions. Far more troubling for British democracy is how anonymous, factional briefings are simply machine-pressed into newspaper “facts” then spewed out on TV.

“They were always looking to get me,” Driscoll claimed this week. I have read emails dating back to 2020 where the new metro mayor asks Labour officials for the party’s local membership lists used by councillors, MPs and mayors as standard. But not here: IT issues meant the lists supposedly weren’t shareable. Until this year that is, when he was told the upcoming mayoral contest meant he could only access lists “if you make a confirmation that you are not seeking the selection”. Another email, sent by Driscoll last month to party officials, notes that a local constituency party has been told by a senior official to disinvite him from speaking.

Asked for comment, Labour didn’t reply – but this is petty, attritional stuff, which is what happens when politics is evacuated of ideas and arguments and becomes simply about who is in whose good books. Cliqueishness is hardly exclusive to Keir Starmer’s Labour, but it is starker now because instead of real politics all this lot have is office politics.

Which brings us back to the much-discussed NEC panel, supposedly to divine his suitability to stand. I have viewed footage of the entire hour on Zoom, which discusses nothing of Driscoll’s beliefs or achievements. Three of the five panel members are from groups on the right of the party, and all anyone wants to know is why he spoke to Loach. They refer to the director’s “controversial views” and quote the Jewish Chronicle’s coverage. How, they ask, might the event be viewed by a “hostile media”?

Driscoll replies that Holocaust denial is “abhorrent” and that he has signed up to the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s definition of antisemitism. He recalls how he used to fight fascists in the street. None of it is good enough.

A rather bumptious young man informs the mayor that “you can’t separate someone’s views from their work”. The twentysomething declares that Driscoll shouldn’t have discussed the films but instead attacked Loach’s politics. On that basis, Starmer ought to be disqualified for appearing with Loach on the BBC’s Question Time – and so too should the shadow foreign secretary, David Lammy, who in 2019 wrote a paean in this paper to Loach’s Sorry We Missed You, praising the way it “brings across how the right to a family life has been eroded in modern Britain”.

We all know that a week is a long time in Starmer’s politics, but he did once proclaim a proud regionalism. Now what’s left?

Attacking McCarthyism, Ed Murrow told his TV audience: “We must not confuse dissent with disloyalty. We must remember always that accusation is not proof and that conviction depends upon evidence and due process of law. We will not walk in fear, one of another.”

By these standards, Driscoll is a victim of McCarthyism. The office he holds is now a mere electoral toy to be enjoyed by a favoured faction. And those people in Newbiggin and Ashington and anyone else who might be looking on with half an eye will see nothing but machine politicians serving themselves. This was the swamp out of which Nigel Farage emerged.

Sunday, 14 May 2023

Are smart people deliberately acting stupid? The Rise of the Anti-Intellectual

Nadeem Paracha in The Dawn

Across the 20th century, intellectuals played an important role in political parties and governments, both democratic and authoritarian. According to Richmond University’s Professor of Politics Eunice Goes, intellectuals perform several roles in the policy-making process.

They help politicians make sense of the world. They offer cause-effect explanations of political and economic phenomena, and diagnoses and prescriptions to policy puzzles. They also help political actors develop ideas and narratives that are consistent with their ideological traditions and political goals.

But in this century, politics has often witnessed a backlash against the presence of intellectuals in political parties and in governments. This is likely due to the strengthening of the parallel tradition of anti-intellectualism, which was always (and still is) active in various polities.

This tradition has been more active in right-wing groups. It was especially strengthened by the rise of populist politics in many countries in the 2010s. But mainstream political outfits in Europe and the US still induct the services of intellectuals, even though this ploy has greatly been eroded in the Republican Party in the US after it wholeheartedly embraced populism in 2016, and still seems to be engulfed by it.

Since the 1930s, the Democratic Party in the US has always had the largest presence of intellectuals in it. This policy was initiated during the four presidential terms of the Democratic Party’s Franklin D. Roosevelt (1932-45), during which time a large number of intellectuals were inducted. Their role was to aid the government in bailing the US out of a tumultuous economic crisis, and to develop a narrative to neutralise the increasing appeal of organisations on the far right and the far left. This tradition of inducting intellectuals continued to be employed by the Democrats for decades.

Interestingly, even though the Republican Party has had an anti-intellectual dimension ever since the early 20th century, it carried with it intellectuals to counter intellectuals active in the Democratic Party. This was specifically true during the presidencies of the Republican Ronald Reagan (1981-88) who was, in fact, propelled to power by an intellectual movement led by conservatives and some former liberals. This movement evolved into becoming ‘neo-conservatism’ during the Reagan presidencies. Britain’s Labour Party and Conservative Party have carried with them intellectuals as well, especially the Labour Party.

Some totalitarian regimes too employed the services of intellectuals in the Soviet Union, Germany and Italy. The Soviet dictator Stalin was not very kind to intellectuals, though. But intellectuals played a major role in shaping Soviet communism. Hitler’s Nazi regime had the services of some of the period’s finest minds in Germany, such as the philosophers Carl Schmitt and Martin Heidegger, the logician Rudolf Carnap, and a host of others.

They helped Hitler mould Nazism into an all-encompassing ideology. Just how could some extremely intelligent men start to both romance as well as rationalise a brutal ideology is a topic that has often been investigated, but it is beyond the scope of this column.

In Pakistan, three governments banked heavily on intellectuals to formulate their respective ideologies, narratives and economics. The Ayub Khan dictatorship (1958-69) carried scholars who specialised in providing ‘modernist’ interpretations to various traditional aspects of Islam. This they did to aid Ayub’s modernisation project. The intellectuals included the rationalist Islamic scholars Fazalur Rahman Malik and Ghulam Ahmad Parwez, and, to a certain extent, the progressive novelist Mumtaz Mufti and Justice Javed Iqbal, the son of the poet-philosopher Muhammad Iqbal. The writer Qudrat Ullah Shahab was Ayub’s Principal Secretary.

Z.A. Bhutto’s Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) was studded with intellectuals who remained active in the party during at least the first few years of Bhutto’s regime (1971-77). These included the Marxist theorist JA Rahim who (with Bhutto) wrote the party’s ‘Foundation Papers’ and then its first manifesto. He also served as a minister in the Bhutto regime till his acrimonious ouster in 1975.

Then there was Dr Mubashir Hassan, who was the main theorist behind PPP’s concept of a ‘planned economy’. He served as the Bhutto regime’s finance minister. The intellectuals Hanif Ramay and Safdar Mir wrote treatises to counter the ideologies of the Islamists. Ramay also formulated the party’s core ideology of ‘Islamic socialism’. The lawyer and constitutional expert Hafeez Pirzada too was a founding member of the party. He was one of the main authors of the 1973 Constitution.

The Ziaul Haq dictatorship adopted the Islamist theorist Abul Ala Maududi as the regime’s main ideologue. Maududi was also the chief of the Jamaat-i-Islami (JI). Zia, when he was a lieutenant general in the early 1970s, used to distribute books written by Maududi to his officers and soldiers. Maududi passed away in 1979, just two years after Zia overthrew the Bhutto regime. But Zia continued to apply Maududi’s ideas to his dictatorship’s ‘Islamisation’ project.

Zia also had the services of the prominent lawyers AK Brohi and Sharifuddin Pirzada. Brohi and Pirzada were instrumental in formulating the murder charges against Bhutto. In his book, Betrayals of Another Kind, Gen Faiz Ali Chisti wrote that Brohi and Pirzada encouraged Zia to hang Bhutto, which he did. Pirzada also wrote oaths for judges sworn in by Zia that omitted the commitment to protect the Constitution. He would go on to do the same for the Musharraf dictatorship (1999-2008). In fact, Sharifuddin Pirzada had also served the Ayub regime.

The rise of populist politics in the second decade of the 21st century has greatly diminished the role of intellectuals in political parties and governments. This is because populism is inherently anti-intellectual. It perceives intellectuals as being part of a detested elite. Therefore, for example, one never expected intellectuals of any kind in Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI). This is why the nature of this party’s narrative is ridiculously contradictory and even chaotic.

However, in a January 2022 essay for The Atlantic, David A. Graham wrote that it’s not that intellectuals have vanished from political parties. Rather, due to populism’s anti-intellectual disposition, they have purposely dumbed down their ideas.

According to Graham, “This is the age of smart politicians pretending to be stupid.” If stupidity can now attract votes and save the jobs of intellectuals in parties and governments, then smart folks can act stupid in the most convincing manner. Even more than those who are actually stupid.

Across the 20th century, intellectuals played an important role in political parties and governments, both democratic and authoritarian. According to Richmond University’s Professor of Politics Eunice Goes, intellectuals perform several roles in the policy-making process.

They help politicians make sense of the world. They offer cause-effect explanations of political and economic phenomena, and diagnoses and prescriptions to policy puzzles. They also help political actors develop ideas and narratives that are consistent with their ideological traditions and political goals.

But in this century, politics has often witnessed a backlash against the presence of intellectuals in political parties and in governments. This is likely due to the strengthening of the parallel tradition of anti-intellectualism, which was always (and still is) active in various polities.

This tradition has been more active in right-wing groups. It was especially strengthened by the rise of populist politics in many countries in the 2010s. But mainstream political outfits in Europe and the US still induct the services of intellectuals, even though this ploy has greatly been eroded in the Republican Party in the US after it wholeheartedly embraced populism in 2016, and still seems to be engulfed by it.

Since the 1930s, the Democratic Party in the US has always had the largest presence of intellectuals in it. This policy was initiated during the four presidential terms of the Democratic Party’s Franklin D. Roosevelt (1932-45), during which time a large number of intellectuals were inducted. Their role was to aid the government in bailing the US out of a tumultuous economic crisis, and to develop a narrative to neutralise the increasing appeal of organisations on the far right and the far left. This tradition of inducting intellectuals continued to be employed by the Democrats for decades.

Interestingly, even though the Republican Party has had an anti-intellectual dimension ever since the early 20th century, it carried with it intellectuals to counter intellectuals active in the Democratic Party. This was specifically true during the presidencies of the Republican Ronald Reagan (1981-88) who was, in fact, propelled to power by an intellectual movement led by conservatives and some former liberals. This movement evolved into becoming ‘neo-conservatism’ during the Reagan presidencies. Britain’s Labour Party and Conservative Party have carried with them intellectuals as well, especially the Labour Party.

Some totalitarian regimes too employed the services of intellectuals in the Soviet Union, Germany and Italy. The Soviet dictator Stalin was not very kind to intellectuals, though. But intellectuals played a major role in shaping Soviet communism. Hitler’s Nazi regime had the services of some of the period’s finest minds in Germany, such as the philosophers Carl Schmitt and Martin Heidegger, the logician Rudolf Carnap, and a host of others.

They helped Hitler mould Nazism into an all-encompassing ideology. Just how could some extremely intelligent men start to both romance as well as rationalise a brutal ideology is a topic that has often been investigated, but it is beyond the scope of this column.

In Pakistan, three governments banked heavily on intellectuals to formulate their respective ideologies, narratives and economics. The Ayub Khan dictatorship (1958-69) carried scholars who specialised in providing ‘modernist’ interpretations to various traditional aspects of Islam. This they did to aid Ayub’s modernisation project. The intellectuals included the rationalist Islamic scholars Fazalur Rahman Malik and Ghulam Ahmad Parwez, and, to a certain extent, the progressive novelist Mumtaz Mufti and Justice Javed Iqbal, the son of the poet-philosopher Muhammad Iqbal. The writer Qudrat Ullah Shahab was Ayub’s Principal Secretary.

Z.A. Bhutto’s Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) was studded with intellectuals who remained active in the party during at least the first few years of Bhutto’s regime (1971-77). These included the Marxist theorist JA Rahim who (with Bhutto) wrote the party’s ‘Foundation Papers’ and then its first manifesto. He also served as a minister in the Bhutto regime till his acrimonious ouster in 1975.

Then there was Dr Mubashir Hassan, who was the main theorist behind PPP’s concept of a ‘planned economy’. He served as the Bhutto regime’s finance minister. The intellectuals Hanif Ramay and Safdar Mir wrote treatises to counter the ideologies of the Islamists. Ramay also formulated the party’s core ideology of ‘Islamic socialism’. The lawyer and constitutional expert Hafeez Pirzada too was a founding member of the party. He was one of the main authors of the 1973 Constitution.

The Ziaul Haq dictatorship adopted the Islamist theorist Abul Ala Maududi as the regime’s main ideologue. Maududi was also the chief of the Jamaat-i-Islami (JI). Zia, when he was a lieutenant general in the early 1970s, used to distribute books written by Maududi to his officers and soldiers. Maududi passed away in 1979, just two years after Zia overthrew the Bhutto regime. But Zia continued to apply Maududi’s ideas to his dictatorship’s ‘Islamisation’ project.

Zia also had the services of the prominent lawyers AK Brohi and Sharifuddin Pirzada. Brohi and Pirzada were instrumental in formulating the murder charges against Bhutto. In his book, Betrayals of Another Kind, Gen Faiz Ali Chisti wrote that Brohi and Pirzada encouraged Zia to hang Bhutto, which he did. Pirzada also wrote oaths for judges sworn in by Zia that omitted the commitment to protect the Constitution. He would go on to do the same for the Musharraf dictatorship (1999-2008). In fact, Sharifuddin Pirzada had also served the Ayub regime.

The rise of populist politics in the second decade of the 21st century has greatly diminished the role of intellectuals in political parties and governments. This is because populism is inherently anti-intellectual. It perceives intellectuals as being part of a detested elite. Therefore, for example, one never expected intellectuals of any kind in Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI). This is why the nature of this party’s narrative is ridiculously contradictory and even chaotic.

However, in a January 2022 essay for The Atlantic, David A. Graham wrote that it’s not that intellectuals have vanished from political parties. Rather, due to populism’s anti-intellectual disposition, they have purposely dumbed down their ideas.

According to Graham, “This is the age of smart politicians pretending to be stupid.” If stupidity can now attract votes and save the jobs of intellectuals in parties and governments, then smart folks can act stupid in the most convincing manner. Even more than those who are actually stupid.

Monday, 13 September 2021

Tuesday, 11 June 2019

How India could sidestep the Middle Income Trap

Rathin Roy - Economic Adviser to the Indian Government

Wednesday, 20 June 2018

Democratising the knowledge of Economics - What happens when ordinary people learn economics?

Aditya Chakrabortty in The Guardian

In a makeshift classroom, nine lay people are battling some of the greatest economists of all time – and they appear to be winning. Just watch what happens to David Ricardo, the 18th-century father of our free-trade system. In best BBC voice, one of the group reads out Ricardo’s words: “Economics studies how the produce of the Earth is distributed.”

Not good enough, says another, Brigitte Lechner. Shouldn’t economists study how to meet basic needs? “We all need a roof over our heads, we all need to survive.” Nor does the Earth belong solely to humans. Her judgment is brisk. “Ricardo was talking tosh.”

So much laughter rings out of this room that the folk outside must wonder what’s going on. They’ve been told this is an economics course – and participants on those don’t normally dissolve into giggles.

Inside, Pat Bhatt chimes in: “Everything you see around you comes from nature. That’s the basis of everything. Economics is the wrong word. It should be … ecolo-mics.”

Ooohs and aaahs. “Very clever!” beams the facilitator Nicola Headlam and scribbles it down on the flipboard.

“I invented it,” says Bhatt.

“My work here is done,” replies Headlam. “I’ll get my coat.”

Some days, democracy looks like a bashed-up ballot box. Some days, it looks like a furious demo. But on this sun-splashed weekday morning, democracy looks like this low-ceilinged meeting room in a converted church, slap bang in the middle of the road that runs from Manchester to Stockport.

None of the “students” have ever picked up an economics textbook. At a guess, most would be either stumped or sedated by the Financial Times. Yet here they are, starting a crash course in something that to them is a mystery. The majority are retired, having worked their entire lives. But when asked how many of them feel some control over the economy, not one raises a hand. So who is in charge?

“Journalists – who are paid by rich people.”

Amid all the humour pokes a truth. For this group, economics is something that’s done to them, by people sitting far away in Westminster or the City. They bear the brunt of spending cuts; they struggle with the rottenness of Northern Rail and they see neighbours sinking into debt – and they have no decent account as to why. They have been bashed over the head again and again, and not even been shown the offending shovel.

Over in the corner sits Sue O’Connor, who today comes “sponsored by Visa!” Another gentle joke that masks the debtor’s panic of having her disability benefit hacked back. Cancer meant she lost all her income and wound up in sheltered housing. Now 64, she suffers severe arthritis, yet her Motability caris about to be taken away.

While at a secondary modern, her class was judged too thick to learn any maths. Partly because the teenager wasn’t taught to count, the grey-haired woman still feels she doesn’t count. “Information is power,” she tells the group. “If I can learn in this class, maybe others will listen to me.”

More confident is 70-year-old “raging feminist” Lechner. “The economy is a system, right?” she says. “I understand systems like patriarchy and how it’s set so certain people get hurt … and I want to know how the rules of the economy are set.”

Headlam nods: “Somehow, someone, somewhere made these rules up. They aren’t laws of nature.” And they determine “who’s got what and where and why”.

‘Short of paying nine grand a year for a degree, how else are laypeople meant to find out about the most potent social science of all?’ A flyer for the course. Photograph: Christopher Thomond for the Guardian

That tearing sound you can hear is the veil that normally partitions economics from society and politics.

Up till 2008, someone like O’Connor would have been told over and over that if she’d failed to get ahead it was her fault, not the system’s. She’d just not followed the rules. Then came the financial crisis, which turned into a crisis of economics.

When the Queen famously asked why no economist saw the crash coming, she cut to the heart of the matter: perhaps those who wrote the economy’s laws and policed their observance weren’t so qualified after all. And while some practitioners claim that theirs is a semi-science, all prescriptions to revive the economy – from George Osborne’s historic austerity to the hundreds of billions doled out to asset-owners by the Bank of England – underline how it’s fundamentally political. By the time Michael Gove remarked in the Brexit campaign that “people in this country have had enough of experts”, he was picking a squelchy-soft target.

One of the biggest battles over economics kicked off just up the road from this community centre. At the University of Manchester in 2013, economics undergraduates – tired of memorising abstract models while the eurozone burned – linked up with students from around the world to demand their economics curriculum be changed. Nothing beyond the orthodoxy of free-market economics was being taught; no conflicting global developments, nothing of its critics such as Keynes or Marx, despite their contemporary relevance. Thus began an epic, and epically imbalanced, fight of a bunch of teenagers taking on the very professors marking their exam papers.

Student passions usually fizzle out faster than you can say “snakebite and black”, yet a half decade on, the struggle to prise open economics has got broader. Those ardent undergraduates propping up the union bar are now civil servants pushing for change in government economics; or they’re directing charities such as Economy, which is putting on this crash course in Levenshulme. The aim is to nail the format, then do 15 courses next year, partnering with housing associations, local authorities and others across the UK.

As you might expect from the first session of the first course, this morning’s proceedings betray some nerves. In an ordinary jacket and denim skirt, Headlam tells the class: “We had no idea if you would come.” Unlike the brogue-wearing professoriat, she and her co-facilitator Anne Hines give no sense that they come from a distant planet. Tomorrow morning, former pharmacist Hines sits her own economics exam for an Open University degree course while Headlam, even with her doctorate, describes her academic career as making “target practice for the elite institutions”.

‘Levenshulme is supposed to be gentrifying.’ Photograph: Christopher Thomond for the Guardian

The pair are giving their time for free, and attendees don’t pay a penny. Economy’s Clare Birkett put together the course and organised the pilots on a part-time wage. All five courses, each lasting up to two months and educating anywhere between 50 and 80 people, will together cost little more than the tuition fees for one solitary economics degree.

A few academic economists will ask what authority a bunch of amateurs have, but Birkett has prepared her fighting talk: “If they say, ‘How dare you talk about this?’, I’ll say, ‘Why shouldn’t I? I’ve put in the work, I’ve studied these things. This stuff belongs to all of us.’”

Short of paying nine grand a year for a degree, how else are lay people meant to find out about the most potent social science of all? The internet is full of blind alleys, while even public lectures within universities typically assume some prior knowledge. Given how some economists rage that they’re not listened to enough on issues such as Brexit, it’s notable how little they actually engage with the public (one excellent exception is the annual Bristol Festival of Economics).

Not so long ago, a Levenshulme resident could learn economics – or any number of other subjects – through the adult evening classes offered by the University of Manchester. The extramural programme stretched as far afield as Wigan and Burnley, and by the 1970s employed more than 30 academic staff. Then followed decades of cuts, until the entire department was shut down in 2006.

Which makes economics the humpty-dumpty subject: trust in it is thoroughly broken, yet the public lack the basic tools to put the discipline back together again in a form that reflects their needs. A YouGov survey in 2015 found that more than 60% of respondents did not even know the definition of GDP (gross domestic product) – that staple of BBC bulletins and Westminster debates.

To make the economy more democratic, as everyone from Theresa May to Jeremy Corbyn proposes, we need to democratise knowledge of economics. That’s a truth now cottoned on to by organisations as disparate as the Bank of England and Momentum.

‘Everyone here brings their own lived experience of economics.’ Photograph: Christopher Thomond for the Guardian

Those doing the Levenshulme crash course don’t look like your typical seminar room attendees. Not only are they decades older; all but one is a women. The average undergraduate economics course, according to the Royal Economic Society, is about 67% male and 25% privately educated(compared with 7% of the population). After the class, a charity van pulls up outside, offering three bags of short-dated food for £6. Several “students” collect their groceries for the week.

Everyone here brings their own lived experience of economics. In her motorised wheelchair, Joanne Wilcock notes how “everything is much more expensive when you’re disabled”. Bang on, yet you hardly ever read that in an article on the latest inflation figures. Bhatt knows that Levenshulme is supposed to be gentrifying – “fancy cars, flash weddings” – but notices his neighbours can’t afford to do up their own houses. “All fur coat and no knickers!” he concludes, and the room cracks up.

And if you’re expecting them to trot out the usual left-itudes about fixing the economy, you’re wrong. A discussion about Northern Rail does produce calls for nationalisation – but also arguments as to how it should be turned into a co-op, or run by an arms-length organisation of technocrats.Q&A

Share your storiesShow

Lechner starts on about “citizen scientists” – amateurs who conduct their own experiments – and casts an eye around the room. “Why can’t we be citizen economists?”

That may be the most radical suggestion of the day, because it cuts directly against how both right and left usually do their business. In 1894, the year before cofounding the London School of Economics, Fabian Beatrice Webb confided to her diary: “We have little faith in the ‘average sensual man’. We do not believe that he can do more than describe his grievances, we do not think he can prescribe his remedies … we wish to introduce into politics the professional expert.”

That impulse may now be dressed up in polite euphemism – but it lives on. “So many thinktanks and MPs come up with good ideas to change our economy, but they’re all stuck in their political bubble,” says the head of Economy, Joe Earle. “Ordinary people barely get a say in the thing that rules their lives.”

Contrast that with this class and its polite horizontalism, where no one is presumed to be a total expert and everyone is treated as if they have something valuable to say. It is the seeds of that ferment described by Hilary Wainwright in her recent book, A New Politics from the Left.

‘Aklima Akhter only came to this country in 2013.’ Photograph: Christopher Thomond for the Guardian

Drawing on her experience of feminist and workers’ self-organisation, she writes: “Rebel movements shared and developed their own kinds of knowledge, via practice and through debate and deliberation, and on to producing new ideas and the basis of new institutions. Authority, once it has been confidently questioned by those on whose obedience it depends, crumbles in ways that make it difficult to put back together again.”

At the end of the class, each participant tells the rest the best thing they have learned. There’s a pause when it gets to Aklima Akhter, who only came to this country in 2013 and has been sitting so benignly quiet in her white headscarf. She starts haltingly: “It is difficult for me, you know … the subject, the language.”

All around her are faces pursed in little moues of encouragement, but then Akhter speeds up with fluency. “But my favourite word was ‘nationalisation’. Because when things are privatised it is the rich who get all the benefit.” And for once in this room, no one is laughing.

In a makeshift classroom, nine lay people are battling some of the greatest economists of all time – and they appear to be winning. Just watch what happens to David Ricardo, the 18th-century father of our free-trade system. In best BBC voice, one of the group reads out Ricardo’s words: “Economics studies how the produce of the Earth is distributed.”

Not good enough, says another, Brigitte Lechner. Shouldn’t economists study how to meet basic needs? “We all need a roof over our heads, we all need to survive.” Nor does the Earth belong solely to humans. Her judgment is brisk. “Ricardo was talking tosh.”

So much laughter rings out of this room that the folk outside must wonder what’s going on. They’ve been told this is an economics course – and participants on those don’t normally dissolve into giggles.

Inside, Pat Bhatt chimes in: “Everything you see around you comes from nature. That’s the basis of everything. Economics is the wrong word. It should be … ecolo-mics.”

Ooohs and aaahs. “Very clever!” beams the facilitator Nicola Headlam and scribbles it down on the flipboard.

“I invented it,” says Bhatt.

“My work here is done,” replies Headlam. “I’ll get my coat.”

Some days, democracy looks like a bashed-up ballot box. Some days, it looks like a furious demo. But on this sun-splashed weekday morning, democracy looks like this low-ceilinged meeting room in a converted church, slap bang in the middle of the road that runs from Manchester to Stockport.

None of the “students” have ever picked up an economics textbook. At a guess, most would be either stumped or sedated by the Financial Times. Yet here they are, starting a crash course in something that to them is a mystery. The majority are retired, having worked their entire lives. But when asked how many of them feel some control over the economy, not one raises a hand. So who is in charge?

“Journalists – who are paid by rich people.”

Amid all the humour pokes a truth. For this group, economics is something that’s done to them, by people sitting far away in Westminster or the City. They bear the brunt of spending cuts; they struggle with the rottenness of Northern Rail and they see neighbours sinking into debt – and they have no decent account as to why. They have been bashed over the head again and again, and not even been shown the offending shovel.

Over in the corner sits Sue O’Connor, who today comes “sponsored by Visa!” Another gentle joke that masks the debtor’s panic of having her disability benefit hacked back. Cancer meant she lost all her income and wound up in sheltered housing. Now 64, she suffers severe arthritis, yet her Motability caris about to be taken away.

While at a secondary modern, her class was judged too thick to learn any maths. Partly because the teenager wasn’t taught to count, the grey-haired woman still feels she doesn’t count. “Information is power,” she tells the group. “If I can learn in this class, maybe others will listen to me.”

More confident is 70-year-old “raging feminist” Lechner. “The economy is a system, right?” she says. “I understand systems like patriarchy and how it’s set so certain people get hurt … and I want to know how the rules of the economy are set.”

Headlam nods: “Somehow, someone, somewhere made these rules up. They aren’t laws of nature.” And they determine “who’s got what and where and why”.

‘Short of paying nine grand a year for a degree, how else are laypeople meant to find out about the most potent social science of all?’ A flyer for the course. Photograph: Christopher Thomond for the Guardian

That tearing sound you can hear is the veil that normally partitions economics from society and politics.

Up till 2008, someone like O’Connor would have been told over and over that if she’d failed to get ahead it was her fault, not the system’s. She’d just not followed the rules. Then came the financial crisis, which turned into a crisis of economics.

When the Queen famously asked why no economist saw the crash coming, she cut to the heart of the matter: perhaps those who wrote the economy’s laws and policed their observance weren’t so qualified after all. And while some practitioners claim that theirs is a semi-science, all prescriptions to revive the economy – from George Osborne’s historic austerity to the hundreds of billions doled out to asset-owners by the Bank of England – underline how it’s fundamentally political. By the time Michael Gove remarked in the Brexit campaign that “people in this country have had enough of experts”, he was picking a squelchy-soft target.

One of the biggest battles over economics kicked off just up the road from this community centre. At the University of Manchester in 2013, economics undergraduates – tired of memorising abstract models while the eurozone burned – linked up with students from around the world to demand their economics curriculum be changed. Nothing beyond the orthodoxy of free-market economics was being taught; no conflicting global developments, nothing of its critics such as Keynes or Marx, despite their contemporary relevance. Thus began an epic, and epically imbalanced, fight of a bunch of teenagers taking on the very professors marking their exam papers.

Student passions usually fizzle out faster than you can say “snakebite and black”, yet a half decade on, the struggle to prise open economics has got broader. Those ardent undergraduates propping up the union bar are now civil servants pushing for change in government economics; or they’re directing charities such as Economy, which is putting on this crash course in Levenshulme. The aim is to nail the format, then do 15 courses next year, partnering with housing associations, local authorities and others across the UK.

As you might expect from the first session of the first course, this morning’s proceedings betray some nerves. In an ordinary jacket and denim skirt, Headlam tells the class: “We had no idea if you would come.” Unlike the brogue-wearing professoriat, she and her co-facilitator Anne Hines give no sense that they come from a distant planet. Tomorrow morning, former pharmacist Hines sits her own economics exam for an Open University degree course while Headlam, even with her doctorate, describes her academic career as making “target practice for the elite institutions”.

‘Levenshulme is supposed to be gentrifying.’ Photograph: Christopher Thomond for the Guardian

The pair are giving their time for free, and attendees don’t pay a penny. Economy’s Clare Birkett put together the course and organised the pilots on a part-time wage. All five courses, each lasting up to two months and educating anywhere between 50 and 80 people, will together cost little more than the tuition fees for one solitary economics degree.

A few academic economists will ask what authority a bunch of amateurs have, but Birkett has prepared her fighting talk: “If they say, ‘How dare you talk about this?’, I’ll say, ‘Why shouldn’t I? I’ve put in the work, I’ve studied these things. This stuff belongs to all of us.’”

Short of paying nine grand a year for a degree, how else are lay people meant to find out about the most potent social science of all? The internet is full of blind alleys, while even public lectures within universities typically assume some prior knowledge. Given how some economists rage that they’re not listened to enough on issues such as Brexit, it’s notable how little they actually engage with the public (one excellent exception is the annual Bristol Festival of Economics).

Not so long ago, a Levenshulme resident could learn economics – or any number of other subjects – through the adult evening classes offered by the University of Manchester. The extramural programme stretched as far afield as Wigan and Burnley, and by the 1970s employed more than 30 academic staff. Then followed decades of cuts, until the entire department was shut down in 2006.

Which makes economics the humpty-dumpty subject: trust in it is thoroughly broken, yet the public lack the basic tools to put the discipline back together again in a form that reflects their needs. A YouGov survey in 2015 found that more than 60% of respondents did not even know the definition of GDP (gross domestic product) – that staple of BBC bulletins and Westminster debates.

To make the economy more democratic, as everyone from Theresa May to Jeremy Corbyn proposes, we need to democratise knowledge of economics. That’s a truth now cottoned on to by organisations as disparate as the Bank of England and Momentum.

‘Everyone here brings their own lived experience of economics.’ Photograph: Christopher Thomond for the Guardian

Those doing the Levenshulme crash course don’t look like your typical seminar room attendees. Not only are they decades older; all but one is a women. The average undergraduate economics course, according to the Royal Economic Society, is about 67% male and 25% privately educated(compared with 7% of the population). After the class, a charity van pulls up outside, offering three bags of short-dated food for £6. Several “students” collect their groceries for the week.

Everyone here brings their own lived experience of economics. In her motorised wheelchair, Joanne Wilcock notes how “everything is much more expensive when you’re disabled”. Bang on, yet you hardly ever read that in an article on the latest inflation figures. Bhatt knows that Levenshulme is supposed to be gentrifying – “fancy cars, flash weddings” – but notices his neighbours can’t afford to do up their own houses. “All fur coat and no knickers!” he concludes, and the room cracks up.

And if you’re expecting them to trot out the usual left-itudes about fixing the economy, you’re wrong. A discussion about Northern Rail does produce calls for nationalisation – but also arguments as to how it should be turned into a co-op, or run by an arms-length organisation of technocrats.Q&A

Share your storiesShow

Lechner starts on about “citizen scientists” – amateurs who conduct their own experiments – and casts an eye around the room. “Why can’t we be citizen economists?”

That may be the most radical suggestion of the day, because it cuts directly against how both right and left usually do their business. In 1894, the year before cofounding the London School of Economics, Fabian Beatrice Webb confided to her diary: “We have little faith in the ‘average sensual man’. We do not believe that he can do more than describe his grievances, we do not think he can prescribe his remedies … we wish to introduce into politics the professional expert.”

That impulse may now be dressed up in polite euphemism – but it lives on. “So many thinktanks and MPs come up with good ideas to change our economy, but they’re all stuck in their political bubble,” says the head of Economy, Joe Earle. “Ordinary people barely get a say in the thing that rules their lives.”

Contrast that with this class and its polite horizontalism, where no one is presumed to be a total expert and everyone is treated as if they have something valuable to say. It is the seeds of that ferment described by Hilary Wainwright in her recent book, A New Politics from the Left.

‘Aklima Akhter only came to this country in 2013.’ Photograph: Christopher Thomond for the Guardian

Drawing on her experience of feminist and workers’ self-organisation, she writes: “Rebel movements shared and developed their own kinds of knowledge, via practice and through debate and deliberation, and on to producing new ideas and the basis of new institutions. Authority, once it has been confidently questioned by those on whose obedience it depends, crumbles in ways that make it difficult to put back together again.”

At the end of the class, each participant tells the rest the best thing they have learned. There’s a pause when it gets to Aklima Akhter, who only came to this country in 2013 and has been sitting so benignly quiet in her white headscarf. She starts haltingly: “It is difficult for me, you know … the subject, the language.”

All around her are faces pursed in little moues of encouragement, but then Akhter speeds up with fluency. “But my favourite word was ‘nationalisation’. Because when things are privatised it is the rich who get all the benefit.” And for once in this room, no one is laughing.

Saturday, 1 October 2016

Is globalisation no longer a good thing?

John O'Sullivan in The Economist

THERE IS NOTHING dark, still less satanic, about the Revolution Mill in Greensboro, North Carolina. The tall yellow-brick chimney stack, with red bricks spelling “Revolution” down its length, was built a few years after the mill was established in 1900. It was a booming time for local enterprise. America’s cotton industry was moving south from New England to take advantage of lower wages. The number of mills in the South more than doubled between 1890 and 1900, to 542. By 1938 Revolution Mill was the world’s largest factory exclusively making flannel, producing 50m yards of cloth a year.

The main mill building still has the springy hardwood floors and original wooden joists installed in its heyday, but no clacking of looms has been heard here for over three decades. The mill ceased production in 1982, an early warning of another revolution on a global scale. The textile industry was starting a fresh migration in search of cheaper labour, this time in Latin America and Asia. Revolution Mill is a monument to an industry that lost out to globalisation.

In nearby Thomasville, there is another landmark to past industrial glory: a 30-foot (9-metre) replica of an upholstered chair. The Big Chair was erected in 1950 to mark the town’s prowess in furniture-making, in which North Carolina was once America’s leading state. But the success did not last. “In the 2000s half of Thomasville went to China,” says T.J. Stout, boss of Carsons Hospitality, a local furniture-maker. Local makers of cabinets, dressers and the like lost sales to Asia, where labour-intensive production was cheaper.

The state is now finding new ways to do well. An hour’s drive east from Greensboro is Durham, a city that is bursting with new firms. One is Bright View Technologies, with a modern headquarters on the city’s outskirts, which makes film and reflectors to vary the pattern and diffusion of LED lights. The Liggett and Myers building in the city centre was once the home of the Chesterfield cigarette. The handsome building is now filling up with newer businesses, says Ted Conner of the Durham Chamber of Commerce. Duke University, the centre of much of the city’s innovation, is taking some of the space for labs.

North Carolina exemplifies both the promise and the casualties of today’s open economy. Yet even thriving local businesses there grumble that America gets the raw end of trade deals, and that foreign rivals benefit from unfair subsidies and lax regulation. In places that have found it harder to adapt to changing times, the rumblings tend to be louder. Across the Western world there is growing unease about globalisation and the lopsided, unstable sort of capitalism it is believed to have wrought.

A backlash against freer trade is reshaping politics. Donald Trump has clinched an unlikely nomination as the Republican Party’s candidate in November’s presidential elections with the support of blue-collar men in America’s South and its rustbelt. These are places that lost lots of manufacturing jobs in the decade after 2001, when America was hit by a surge of imports from China (which Mr Trump says he will keep out with punitive tariffs). Free trade now causes so much hostility that Hillary Clinton, the Democratic Party’s presidential candidate, was forced to disown the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a trade deal with Asia that she herself helped to negotiate. Talks on a new trade deal with the European Union, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), have stalled. Senior politicians in Germany and France have turned against it in response to popular opposition to the pact, which is meant to lower investment and regulatory barriers between Europe and America.

Keep-out signs

The commitment to free movement of people within the EU has also come under strain. In June Britain, one of Europe’s stronger economies, voted in a referendum to leave the EU after 43 years as a member. Support for Brexit was strong in the north of England and Wales, where much of Britain’s manufacturing used to be; but it was firmest in places that had seen big increases in migrant populations in recent years. Since Britain’s vote to leave, anti-establishment parties in France, the Netherlands, Germany, Italy and Austria have called for referendums on EU membership in their countries too. Such parties favour closed borders, caps on migration and barriers to trade. They are gaining in popularity and now hold sway in governments in eight EU countries. Mr Trump, for his part, has promised to build a wall along the border with Mexico to keep out immigrants.

There is growing disquiet, too, about the unfettered movement of capital. More of the value created by companies is intangible, and businesses that rely on selling ideas find it easier to set up shop where taxes are low. America has clamped down on so-called tax inversions, in which a big company moves to a low-tax country after agreeing to be bought by a smaller firm based there. Europeans grumble that American firms engage in too many clever tricks to avoid tax. In August the European Commission told Ireland to recoup up to €13 billion ($14.5 billion) in unpaid taxes from Apple, ruling that the company’s low tax bill was a source of unfair competition.

Free movement of debt capital has meant that trouble in one part of the world (say, America’s subprime crisis) quickly spreads to other parts. The fickleness of capital flows is one reason why the EU’s most ambitious cross-border initiative, the euro, which has joined 19 of its 28 members in a currency union, is in trouble. In the euro’s early years, countries such as Greece, Italy, Ireland, Portugal and Spain enjoyed ample credit and low borrowing costs, thanks to floods of private short-term capital from other EU countries. When crisis struck, that credit dried up and had to be replaced with massive official loans, from the ECB and from bail-out funds. The conditions attached to such support have caused relations between creditor countries such as Germany and debtors such as Greece to sour.

Some claim that the growing discontent in the rich world is not really about economics. After all, Britain and America, at least, have enjoyed reasonable GDP growth recently, and unemployment in both countries has dropped to around 5%. Instead, the argument goes, the revolt against economic openness reflects deeper anxieties about lost relative status. Some arise from the emergence of China as a global power; others are rooted within individual societies. For example, in parts of Europe opposition to migrants was prompted by the Syrian refugee crisis. It stems less from worries about the effect of immigration on wages or jobs than from a perceived threat to social cohesion.

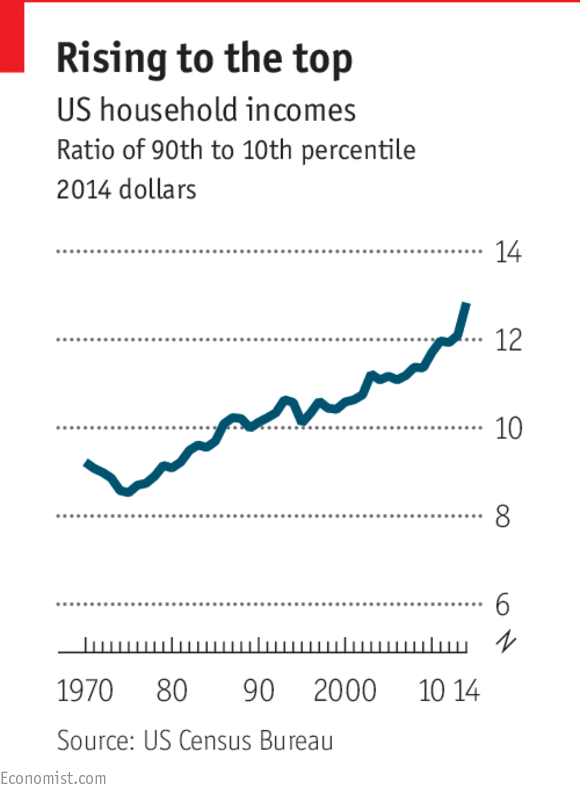

But there is a material basis for discontent nevertheless, because a sluggish economic recovery has bypassed large groups of people. In America one in six working-age men without a college degree is not part of the workforce, according to an analysis by the Council of Economic Advisers, a White House think-tank. In Britain, though more people than ever are in work, wage rises have not kept up with inflation. Only in London and its hinterland in the south-east has real income per person risen above its level before the 2007-08 financial crisis. Most other rich countries are in the same boat. A report by the McKinsey Global Institute, a think-tank, found that the real incomes of two-thirds of households in 25 advanced economies were flat or fell between 2005 and 2014, compared with 2% in the previous decade. The few gains in a sluggish economy have gone to a salaried gentry.

This has fed a widespread sense that an open economy is good for a small elite but does nothing for the broad mass of people. Even academics and policymakers who used to welcome openness unreservedly are having second thoughts. They had always understood that free trade creates losers as well as winners, but thought that the disruption was transitory and the gains were big enough to compensate those who lose out. However, a body of new research suggests that China’s integration into global trade caused more lasting damage than expected to some rich-world workers. Those displaced by a surge in imports from China were concentrated in pockets of distress where alternative jobs were hard to come by.

It is not easy to establish a direct link between openness and wage inequality, but recent studies suggest that trade plays a bigger role than previously thought. Large-scale migration is increasingly understood to conflict with the welfare policy needed to shield workers from the disruptions of trade and technology.

The consensus in favour of unfettered capital mobility began to weaken after the East Asian crises of 1997-98. As the scale of capital flows grew, the doubts increased. A recent article by economists at the IMF entitled “Neoliberalism: Oversold?” argued that in certain cases the costs to economies of opening up to capital flows exceed the benefits.

Multiple hits

This special report will ask how far globalisation, defined as the freer flow of trade, people and capital around the world, is responsible for the world’s economic ills and whether it is still, on balance, a good thing. A true reckoning is trickier than it might appear, and not just because the main elements of economic openness have different repercussions. Several other big upheavals have hit the world economy in recent decades, and the effects are hard to disentangle.

First, jobs and pay have been greatly affected by technological change. Much of the increase in wage inequality in rich countries stems from new technologies that make college-educated workers more valuable. At the same time companies’ profitability has increasingly diverged. Online platforms such as Amazon, Google and Uber that act as matchmakers between consumers and producers or advertisers rely on network effects: the more users they have, the more useful they become. The firms that come to dominate such markets make spectacular returns compared with the also-rans. That has sometimes produced windfalls at the very top of the income distribution. At the same time the rapid decline in the cost of automation has left the low- and mid-skilled at risk of losing their jobs. All these changes have been amplified by globalisation, but would have been highly disruptive in any event.

The second source of turmoil was the financial crisis and the long, slow recovery that typically follows banking blow-ups. The credit boom before the crisis had helped to mask the problem of income inequality by boosting the price of homes and increasing the spending power of the low-paid. The subsequent bust destroyed both jobs and wealth, but the college-educated bounced back more quickly than others. The free flow of debt capital played a role in the build-up to the crisis, but much of the blame for it lies with lax bank regulation. Banking busts happened long before globalisation.

Superimposed on all this was a unique event: the rapid emergence of China as an economic power. Export-led growth has transformed China from a poor to a middle-income country, taking hundreds of millions of people out of poverty. This achievement is probably unrepeatable. As the price of capital goods continues to fall sharply, places with large pools of cheap labour, such as India or Africa, will find it harder to break into global supply chains, as China did so speedily and successfully.

This special report will disentangle these myriad influences to assess the impact of the free movement of goods, capital and people. It will conclude that some of the concerns about economic openness are valid. The strains inflicted by a more integrated global economy were underestimated, and too little effort went into helping those who lost out. But much of the criticism of openness is misguided, underplaying its benefits and blaming it for problems that have other causes. Rolling it back would leave everyone worse off.

THERE IS NOTHING dark, still less satanic, about the Revolution Mill in Greensboro, North Carolina. The tall yellow-brick chimney stack, with red bricks spelling “Revolution” down its length, was built a few years after the mill was established in 1900. It was a booming time for local enterprise. America’s cotton industry was moving south from New England to take advantage of lower wages. The number of mills in the South more than doubled between 1890 and 1900, to 542. By 1938 Revolution Mill was the world’s largest factory exclusively making flannel, producing 50m yards of cloth a year.

The main mill building still has the springy hardwood floors and original wooden joists installed in its heyday, but no clacking of looms has been heard here for over three decades. The mill ceased production in 1982, an early warning of another revolution on a global scale. The textile industry was starting a fresh migration in search of cheaper labour, this time in Latin America and Asia. Revolution Mill is a monument to an industry that lost out to globalisation.

In nearby Thomasville, there is another landmark to past industrial glory: a 30-foot (9-metre) replica of an upholstered chair. The Big Chair was erected in 1950 to mark the town’s prowess in furniture-making, in which North Carolina was once America’s leading state. But the success did not last. “In the 2000s half of Thomasville went to China,” says T.J. Stout, boss of Carsons Hospitality, a local furniture-maker. Local makers of cabinets, dressers and the like lost sales to Asia, where labour-intensive production was cheaper.

The state is now finding new ways to do well. An hour’s drive east from Greensboro is Durham, a city that is bursting with new firms. One is Bright View Technologies, with a modern headquarters on the city’s outskirts, which makes film and reflectors to vary the pattern and diffusion of LED lights. The Liggett and Myers building in the city centre was once the home of the Chesterfield cigarette. The handsome building is now filling up with newer businesses, says Ted Conner of the Durham Chamber of Commerce. Duke University, the centre of much of the city’s innovation, is taking some of the space for labs.

North Carolina exemplifies both the promise and the casualties of today’s open economy. Yet even thriving local businesses there grumble that America gets the raw end of trade deals, and that foreign rivals benefit from unfair subsidies and lax regulation. In places that have found it harder to adapt to changing times, the rumblings tend to be louder. Across the Western world there is growing unease about globalisation and the lopsided, unstable sort of capitalism it is believed to have wrought.

A backlash against freer trade is reshaping politics. Donald Trump has clinched an unlikely nomination as the Republican Party’s candidate in November’s presidential elections with the support of blue-collar men in America’s South and its rustbelt. These are places that lost lots of manufacturing jobs in the decade after 2001, when America was hit by a surge of imports from China (which Mr Trump says he will keep out with punitive tariffs). Free trade now causes so much hostility that Hillary Clinton, the Democratic Party’s presidential candidate, was forced to disown the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a trade deal with Asia that she herself helped to negotiate. Talks on a new trade deal with the European Union, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), have stalled. Senior politicians in Germany and France have turned against it in response to popular opposition to the pact, which is meant to lower investment and regulatory barriers between Europe and America.

Keep-out signs

The commitment to free movement of people within the EU has also come under strain. In June Britain, one of Europe’s stronger economies, voted in a referendum to leave the EU after 43 years as a member. Support for Brexit was strong in the north of England and Wales, where much of Britain’s manufacturing used to be; but it was firmest in places that had seen big increases in migrant populations in recent years. Since Britain’s vote to leave, anti-establishment parties in France, the Netherlands, Germany, Italy and Austria have called for referendums on EU membership in their countries too. Such parties favour closed borders, caps on migration and barriers to trade. They are gaining in popularity and now hold sway in governments in eight EU countries. Mr Trump, for his part, has promised to build a wall along the border with Mexico to keep out immigrants.

There is growing disquiet, too, about the unfettered movement of capital. More of the value created by companies is intangible, and businesses that rely on selling ideas find it easier to set up shop where taxes are low. America has clamped down on so-called tax inversions, in which a big company moves to a low-tax country after agreeing to be bought by a smaller firm based there. Europeans grumble that American firms engage in too many clever tricks to avoid tax. In August the European Commission told Ireland to recoup up to €13 billion ($14.5 billion) in unpaid taxes from Apple, ruling that the company’s low tax bill was a source of unfair competition.

Free movement of debt capital has meant that trouble in one part of the world (say, America’s subprime crisis) quickly spreads to other parts. The fickleness of capital flows is one reason why the EU’s most ambitious cross-border initiative, the euro, which has joined 19 of its 28 members in a currency union, is in trouble. In the euro’s early years, countries such as Greece, Italy, Ireland, Portugal and Spain enjoyed ample credit and low borrowing costs, thanks to floods of private short-term capital from other EU countries. When crisis struck, that credit dried up and had to be replaced with massive official loans, from the ECB and from bail-out funds. The conditions attached to such support have caused relations between creditor countries such as Germany and debtors such as Greece to sour.

Some claim that the growing discontent in the rich world is not really about economics. After all, Britain and America, at least, have enjoyed reasonable GDP growth recently, and unemployment in both countries has dropped to around 5%. Instead, the argument goes, the revolt against economic openness reflects deeper anxieties about lost relative status. Some arise from the emergence of China as a global power; others are rooted within individual societies. For example, in parts of Europe opposition to migrants was prompted by the Syrian refugee crisis. It stems less from worries about the effect of immigration on wages or jobs than from a perceived threat to social cohesion.

But there is a material basis for discontent nevertheless, because a sluggish economic recovery has bypassed large groups of people. In America one in six working-age men without a college degree is not part of the workforce, according to an analysis by the Council of Economic Advisers, a White House think-tank. In Britain, though more people than ever are in work, wage rises have not kept up with inflation. Only in London and its hinterland in the south-east has real income per person risen above its level before the 2007-08 financial crisis. Most other rich countries are in the same boat. A report by the McKinsey Global Institute, a think-tank, found that the real incomes of two-thirds of households in 25 advanced economies were flat or fell between 2005 and 2014, compared with 2% in the previous decade. The few gains in a sluggish economy have gone to a salaried gentry.

This has fed a widespread sense that an open economy is good for a small elite but does nothing for the broad mass of people. Even academics and policymakers who used to welcome openness unreservedly are having second thoughts. They had always understood that free trade creates losers as well as winners, but thought that the disruption was transitory and the gains were big enough to compensate those who lose out. However, a body of new research suggests that China’s integration into global trade caused more lasting damage than expected to some rich-world workers. Those displaced by a surge in imports from China were concentrated in pockets of distress where alternative jobs were hard to come by.

It is not easy to establish a direct link between openness and wage inequality, but recent studies suggest that trade plays a bigger role than previously thought. Large-scale migration is increasingly understood to conflict with the welfare policy needed to shield workers from the disruptions of trade and technology.

The consensus in favour of unfettered capital mobility began to weaken after the East Asian crises of 1997-98. As the scale of capital flows grew, the doubts increased. A recent article by economists at the IMF entitled “Neoliberalism: Oversold?” argued that in certain cases the costs to economies of opening up to capital flows exceed the benefits.

Multiple hits

This special report will ask how far globalisation, defined as the freer flow of trade, people and capital around the world, is responsible for the world’s economic ills and whether it is still, on balance, a good thing. A true reckoning is trickier than it might appear, and not just because the main elements of economic openness have different repercussions. Several other big upheavals have hit the world economy in recent decades, and the effects are hard to disentangle.

First, jobs and pay have been greatly affected by technological change. Much of the increase in wage inequality in rich countries stems from new technologies that make college-educated workers more valuable. At the same time companies’ profitability has increasingly diverged. Online platforms such as Amazon, Google and Uber that act as matchmakers between consumers and producers or advertisers rely on network effects: the more users they have, the more useful they become. The firms that come to dominate such markets make spectacular returns compared with the also-rans. That has sometimes produced windfalls at the very top of the income distribution. At the same time the rapid decline in the cost of automation has left the low- and mid-skilled at risk of losing their jobs. All these changes have been amplified by globalisation, but would have been highly disruptive in any event.

The second source of turmoil was the financial crisis and the long, slow recovery that typically follows banking blow-ups. The credit boom before the crisis had helped to mask the problem of income inequality by boosting the price of homes and increasing the spending power of the low-paid. The subsequent bust destroyed both jobs and wealth, but the college-educated bounced back more quickly than others. The free flow of debt capital played a role in the build-up to the crisis, but much of the blame for it lies with lax bank regulation. Banking busts happened long before globalisation.

Superimposed on all this was a unique event: the rapid emergence of China as an economic power. Export-led growth has transformed China from a poor to a middle-income country, taking hundreds of millions of people out of poverty. This achievement is probably unrepeatable. As the price of capital goods continues to fall sharply, places with large pools of cheap labour, such as India or Africa, will find it harder to break into global supply chains, as China did so speedily and successfully.

This special report will disentangle these myriad influences to assess the impact of the free movement of goods, capital and people. It will conclude that some of the concerns about economic openness are valid. The strains inflicted by a more integrated global economy were underestimated, and too little effort went into helping those who lost out. But much of the criticism of openness is misguided, underplaying its benefits and blaming it for problems that have other causes. Rolling it back would leave everyone worse off.

Thursday, 8 October 2015

Money isn’t restricted by borders, so why are people?

Giles Fraser in The Guardian

Theresa May won’t be around in the early 22nd century when, according to Star Trek at least, Dr Emory Erickson will have invented the transporter – a device that will be able to dematerialise a person into an energy pattern, beam them to another place or planet, and then rematerialise them back again. In such a world people will be able to move as quickly and freely as an email.