'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Friday, 7 April 2023

Friday, 29 July 2022

The strange case of the cricket match that helped fund Imran Khan’s political rise

Simon Clark in The FT

At the height of his success, the Pakistani tycoon Arif Naqvi invited cricket superstar Imran Khan and hundreds of bankers, lawyers and investors to his walled country estate in the Oxfordshire village of Wootton for weekends of sport and drinking. The host was the founder of the Dubai-based Abraaj Group, then one of the largest private equity firms operating in emerging markets, with billions of dollars under management.

At the “Wootton T20 Cup”, over which Naqvi presided from 2010 to 2012, the main event was a cricket tournament between teams with invented names: the Peshawar Perverts or the Faisalabad Fothermuckers. They played on an immaculate pitch amid 14 acres of formal gardens and parkland at Wootton Place, Naqvi’s 17th-century residence. Veteran cricket commentator Henry Blofeld attended along with expert umpires and film crews.

“You can choose to play in order to impress or make a fool of yourself, or alternatively just to be an innocent bystander,” Naqvi wrote in an invitation to the event. The guests were asked to pay between £2,000 and £2,500 each to attend, with the money going to unspecified “philanthropic causes”, Naqvi said.

It is the type of charity fundraiser repeated up and down the UK every summer. What makes it unusual is that the ultimate benefactor was a political party in Pakistan. The fees were paid to Wootton Cricket Ltd, which, despite the name, was in fact a Cayman Islands-incorporated company owned by Naqvi and the money was being used to bankroll Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, Khan’s political party. Funds poured into Wootton Cricket from companies and individuals, including at least £2mn from a United Arab Emirates government minister who is also a member of the Abu Dhabi royal family.

Pakistan forbids foreign nationals and companies from funding political parties, but Abraaj emails and internal documents seen by the Financial Times, including a bank statement covering the period between February 28 and May 30 2013 for a Wootton Cricket account in the UAE, show that both companies and foreign nationals as well as citizens of Pakistan sent millions of dollars to Wootton Cricket — before money was transferred from the account to Pakistan for the PTI.

The funding of the party is at the centre of a years-long investigation by the Election Commission of Pakistan, an inquiry that has taken on even greater importance as Khan — who lost office in April — plots a political comeback.

But back in 2013, Khan — a World Cup-winning cricket captain — was riding a wave of popular support and campaigning to upend Pakistan’s politics on an anti-corruption ticket. He presented himself to the electorate as a democratic reformer — born in Pakistan and with experience of living in the west — who could break the hold of the political family dynasties that had dominated the country for decades.

Although Khan lost the 2013 general election to longtime rival Nawaz Sharif, his party became the third largest in the National Assembly. Naqvi’s star was also rising. His private equity firm was expanding and winning new investors. He became a regular fixture at World Economic Forum meetings in Davos.

In July 2017, Pakistan’s Supreme Court removed Sharif from office over corruption allegations. Khan won the election in July 2018. As prime minister he became increasingly critical of the west, praising Afghanistan’s Taliban when US forces withdrew in 2021, and visiting Vladimir Putin in Moscow on the day Russian forces invaded Ukraine in February.

The Election Commission of Pakistan has been investigating the funding of the PTI for more than seven years. In January, the ECP’s scrutiny committee issued a damning report in which it said the PTI received funding from foreign nationals and companies and accused it of under-reporting funds and concealing dozens of bank accounts. Wootton Cricket was named in the report, but Naqvi wasn’t identified as its owner.

In April, Khan stood down after losing a parliamentary vote of no confidence, triggered in part by rising inflation. He has accused the US of orchestrating the vote and is now attempting to stage a political return to contest a general election due to take place by October 2023.

That re-election effort means that although the Naqvi funding took place almost a decade ago, the controversy around it, and the final findings of the election commission, are likely to be at the forefront of Pakistan politics for some time.

While it has previously been reported that Naqvi funded Khan’s party, the ultimate source of the money has never before been disclosed. Wootton Cricket’s bank statement shows it received $1.3mn on March 14 2013 from Abraaj Investment Management Ltd, the fund management unit of Naqvi’s private equity firm, boosting the account’s previous balance of $5,431. Later the same day, $1.3mn was transferred from the account directly to a PTI bank account in Pakistan. Abraaj expensed the cost to a holding company through which it controlled K-Electric, the power provider to Karachi, Pakistan’s largest city.

A further $2mn flowed into the Wootton Cricket account in April 2013 from Sheikh Nahyan bin Mubarak al-Nahyan, a member of Abu Dhabi’s royal family, government minister and chair of Pakistan’s Bank Alfalah, according to the bank statement and a copy of the Swift transfer details.

Naqvi then exchanged emails with a colleague about transferring $1.2mn more to the PTI. Six days after the $2mn arrived in the Wootton Cricket bank account, Naqvi transferred $1.2mn from it to Pakistan in two instalments. Rafique Lakhani, the senior Abraaj executive responsible for managing cash flow, wrote in an email to Naqvi that the transfers were intended for the PTI. Sheikh Nahyan didn’t respond to requests for comment.

“Like other populists, Khan is made of Teflon,” says Uzair Younus, director of the Pakistan initiative at the Atlantic Council, a Washington-based research group. “But his opponents will try to use the foreign funding controversy to weaken the argument that he is not corrupt,” he adds, and to encourage the election commission to “punish him and his party”.

A useful ally

Naqvi, 62, was born into a Karachi business family. After studying at the London School of Economics he spent the 1990s working in Saudi Arabia and Dubai and started Abraaj in 2002, building it into an investment powerhouse. With offices in Dubai, London, New York and across Asia, Africa and Latin America, the company raised billions of dollars from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the US administration of Barack Obama, the British and French governments and other investors.

Well-connected, Naqvi liked to impress. John Kerry — a speaker at one Abraaj event — was approached by the company about working with it after he served as US secretary of state. Naqvi met Britain’s Prince Charles and was active in one of his charities, the British Asian Trust. He was a board member of the UN Global Compact, which advises the UN secretary-general, and sat alongside former Nissan chair Carlos Ghosn on the board of the Interpol Foundation, which raises funds for the global police organisation.

In Washington he was seen as a useful ally. The Obama administration pledged $150mn to an Abraaj fund investing in Middle Eastern companies: a press release said that the partnership would help turn the US president’s promise to improve economic relations with Islamic nations into a reality. Some even saw him as a possible future political leader in Pakistan, which he once described as “a country not known for transparency”, before adding that Abraaj “did everything by the book” during its control of K-Electric.

“We avoided every single point where you would have had to come into contact with government — even though you were a utility — and have to pay someone something,” he said.

K-Electric was Abraaj’s single largest investment. But as the private equity firm ran into financial difficulties in 2016, Naqvi struck a deal to sell control of the power company to Chinese state-controlled Shanghai Electric Power for $1.77bn. Political approval for the deal in Pakistan was important and Naqvi lobbied the governments of both Sharif and Khan for backing. In 2016, he authorised a $20mn payment for Pakistan politicians to gain their support, according to US public prosecutors who later charged him with fraud, theft and attempted bribery.

The payment was allegedly intended for Nawaz Sharif and his brother Shehbaz, who replaced Khan as prime minister in April. The brothers have denied any knowledge of the matter. In January 2017, Naqvi hosted a dinner for Nawaz Sharif at Davos. After Khan became prime minister, Naqvi met him. While in office Khan criticised officials for delaying the sale of K-Electric but the deal has still not been completed.

Abraaj collapsed in 2018 after investors including the Gates Foundation started investigating whether the company was misusing money in a fund intended to buy and build hospitals across Africa and Asia. Abraaj said it was managing assets of about $14bn at the time. In 2019, US prosecutors indicted Naqvi and five of his former colleagues. Two former Abraaj executives have since pleaded guilty. Naqvi denies the charges.

Naqvi was arrested at London’s Heathrow airport in April 2019 after returning from Pakistan and faces up to 291 years in jail if found guilty of the US charges. Khan’s telephone number was included on a list of contacts he handed to police — a fact mentioned by lawyers representing the US government during Naqvi’s extradition trial in London.

His appeal against extradition to the US is expected to conclude later this year. But he has had to pay £15mn for bail and has hefty ongoing legal expenses. Wootton Place was sold to a hedge fund manager in 2020 for £12.25mn. Naqvi and his lawyer did not respond to requests for comment on this story.

Moving money around

In 2012 Khan visited Wootton Place. In a written response to questions from the FT, the former cricketer said he had gone to “a fundraising event which was attended by many PTI supporters”. Blofeld, the cricket commentator, recalls that Khan “was persuaded to take the field” at Wootton. “It was extraordinary to see how he still had the knack of bowling those fast inswingers,” he says.

Naqvi, a self-described cricket purist, provided the bats, balls, osteopaths, masseurs, food, accommodation and clothing. He literally wrote the rules for the matches. Ball tampering — banned in cricket — was permitted in matches at Wootton because “it is important to encourage innovation and experimentation in cricket, as what is considered illegal today may be de rigueur tomorrow,” Naqvi once wrote to guests.

It was a critical time for Khan to gather funds ahead of the election scheduled for May 2013, and Naqvi worked closely with other Pakistani businessmen to raise money for his campaign. The largest entry in Wootton Cricket’s bank account in the months before the election was the $2mn from Sheikh Nahyan, now the UAE’s minister for tolerance. He is also an investor in Pakistan.

After Lakhani, the Abraaj executive responsible for cash flow, told Naqvi in an email that the sheikh’s money had arrived, Naqvi replied that he should send “1.2 million to PTI”. In another email to Lakhani after the sheikh’s money entered the Wootton Cricket account Naqvi wrote: “do not tell anyone where funds are coming from, ie who is contributing”.

“Sure sir,” Lakhani responded. He wrote that he would transfer $1.2mn from Wootton Cricket to the PTI’s account in Pakistan. Then after considering sending the funds to the PTI via Naqvi’s personal account, Lakhani proposed sending the money in two instalments to a personal account for businessman Tariq Shafi in Karachi and an account for an entity called the Insaf Trust in Lahore. Although the ownership of the Insaf Trust is unclear, the emails state that the final destination was the PTI. “Don’t eff this up rafiq,” Naqvi wrote in another email.

On May 6 2013, Wootton Cricket transferred a total of $1.2mn to Shafi and the Insaf Trust. Lakhani wrote in an email to Naqvi that the transfers were for the PTI. Khan confirmed that Shafi donated to the PTI. “It is for Tariq Shafi to answer as to from where he received this money,” Khan said in response to the FT. Shafi didn’t respond to requests for comment.

‘Prohibited funding took place’

The ECP investigation into the funding of Khan’s party was triggered when Akbar S Babar, who helped establish the PTI, filed a complaint in December 2014. Although thousands of Pakistanis worldwide sent money for the PTI, Babar insists that “prohibited funding took place”.

In his written response, Khan said that neither he nor his party was aware of Abraaj providing $1.3mn through Wootton Cricket. He also said he was “not aware” of the PTI receiving any funds that originated from Sheikh Nahyan. “Arif Naqvi has given a statement which was filed before the Election Commission also, not denied by anyone, that the money came from donations during a cricket match and the money as collected by him was sent through his company Wootton Cricket,” Khan wrote.

Khan said he was waiting for the verdict of the election commission’s investigation. “It will not be appropriate to prejudge PTI.”

In its January report, the election commission said Wootton Cricket had transferred $2.12mn to the PTI but didn’t reveal the original source of the money. Naqvi has acknowledged his ownership of Wootton Cricket and denied any wrongdoing. In a statement, he told the election commission that: “I have not collected any fund from any person of non-Pakistani origin, company [public or private] or any other

The bank statement for Wootton Cricket tells a different story. It shows that Naqvi transferred three instalments directly to the PTI in 2013 adding up to a total of $2.12mn. The largest was the $1.3mn from Abraaj which company documents show was transferred to Wootton Cricket but charged to its holding company for K-Electric.

The impact of the scandal could yet hit Khan’s re-election ambitions. In July he renewed his call for an early poll after the PTI won a critical victory in by-elections in Punjab, Pakistan’s most populous province. On Twitter, he called the Election Commission of Pakistan “totally biased”.

At the same time prime minister Shehbaz Sharif has urged the commission to publish its verdict in the PTI case, saying that the delays caused by political infighting had given Khan “a free pass despite his repeated & shameless attacks on state institutions”.

Yet the Atlantic Council’s Younus says that Khan’s loyal supporters won’t be moved whatever the outcome. They “do not and will not care. In fact, Khan may claim that the story is further evidence that foreign powers are leveraging global media to conspire against him.”

For Babar, who helped found the PTI, the controversy is proof that Khan has fallen short of the ideals they set out to champion in politics. “He had the opportunity of a lifetime and he blew it,” Babar says. “Our cause was reform, change — introduce the values in our politics that we espoused publicly.” Instead, he says, “[Khan’s] morality compass in a political sense went haywire”.

Friday, 6 July 2018

The George Soros philosophy – and its fatal flaw

In late May, the same day she got fired by the US TV network ABC for her racist tweet about Obama adviser Valerie Jarrett, Roseanne Barr accused Chelsea Clinton of being married to George Soros’s nephew. “Chelsea Soros Clinton,” Barr tweeted, knowing that the combination of names was enough to provoke a reaction. In the desultory exchange that followed, the youngest Clinton responded to Roseanne by praising Soros’s philanthropic work with his Open Society Foundations. To which Barr responded in the most depressing way possible, repeating false claims earlier proferred by rightwing media personalities: “Sorry to have tweeted incorrect info about you! Please forgive me! By the way, George Soros is a nazi who turned in his fellow Jews 2 be murdered in German concentration camps & stole their wealth – were you aware of that? But, we all make mistakes, right Chelsea?”

Barr’s tweet was quickly retweeted by conservatives, including Donald Trump Jr. This shouldn’t have surprised anyone. On the radical right, Soros is as hated as the Clintons. He is a verbal tic, a key that fits every hole. Soros’s name evokes “an emotional outcry from the red-meat crowds”, one former Republican congressman recently told the Washington Post. They view him as a “sort of sinister [person who] plays in the shadows”. This antisemitic caricature of Soros has dogged the philanthropist for decades. But in recent years the caricature has evolved into something that more closely resembles a James Bond villain. Even to conservatives who reject the darkest fringes of the far right, Breitbart’s description of Soros as a “globalist billionaire” dedicated to making America a liberal wasteland is uncontroversial common sense.

The trouble with charitable billionaires

In spite of the obsession with Soros, there has been surprisingly little interest in what he actually thinks. Yet unlike most of the members of the billionaire class, who speak in platitudes and remain withdrawn from serious engagement with civic life, Soros is an intellectual. And the person who emerges from his books and many articles is not an out-of-touch plutocrat, but a provocative and consistent thinker committed to pushing the world in a cosmopolitan direction in which racism, income inequality, American empire, and the alienations of contemporary capitalism would be things of the past. He is extremely perceptive about the limits of markets and US power in both domestic and international contexts. He is, in short, among the best the meritocracy has produced.

It is for this reason that Soros’s failures are so telling; they are the failures not merely of one man, but of an entire class – and an entire way of understanding the world. From his earliest days as a banker in postwar London, Soros believed in a necessary connection between capitalism and cosmopolitanism. For him, as for most of the members of his cohort and the majority of the Democratic party’s leadership, a free society depends on free (albeit regulated) markets. But this assumed connection has proven to be a false one. The decades since the end of the cold war have demonstrated that, without a perceived existential enemy, capitalism tends to undermine the very culture of trust, compassion and empathy upon which Soros’s “open society” depends, by concentrating wealth in the hands of the very few.

Instead of the global capitalist utopia predicted in the halcyon 1990s by those who proclaimed an end to history, the US is presently ruled by an oafish heir who enriches his family as he dismantles the “liberal international order” that was supposed to govern a peaceful, prosperous and united world. While Soros recognised earlier than most the limits of hypercapitalism, his class position made him unable to advocate the root-and-branch reforms necessary to bring about the world he desires. The system that allows George Soros to accrue the wealth that he has done has proven to be one in which cosmopolitanism will never find a stable home.

The highlights of Soros’s biography are well known. Born to middle-class Jewish parents in Budapest in 1930 as György Schwartz, Soros – his father changed the family name in 1936 to avoid antisemitic discrimination – had a tranquil childhood until the second world war, when after the Nazi invasion of Hungary he and his family were forced to assume Christian identities and live under false names. Miraculously, Soros and his family survived the war, escaping the fate suffered by more than two-thirds of Hungary’s Jews. Feeling stifled in newly communist Hungary, in 1947 Soros immigrated to the UK, where he studied at the London School of Economics and got to know the Austrian-born philosopher Karl Popper, who became his greatest interlocutor and central intellectual influence.

In 1956, Soros moved to New York to pursue a career in finance. After spending over a decade working in various Wall Street positions, in the late 1960s he founded the Quantum Fund, which became one of the most successful hedge funds of all time. As his fund amassed staggering profits, Soros personally emerged as a legendary trader; most famously, in November 1992 he earned more than $1bn and “broke the Bank of England” by betting that the pound was priced too highly against the Deutschmark.

Karl Popper, whose writings were a key influence on Soros’s thinking about the ‘open society’. Photograph: Popperfoto

Today, Soros is one of the richest men in the world and, along with Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg, one of the US’s most politically influential philanthropists. But unlike Gates and Zuckerberg, Soros has long pointed to academic philosophy as his source of inspiration. Soros’s thought and philanthropic career are organised around the idea of the “open society,” a term developed and popularised by Popper in his classic work The Open Society and Its Enemies. According to Popper, open societies guarantee and protect rational exchange, while closed societies force people to submit to authority, whether that authority is religious, political or economic.

Since 1987, Soros has published 14 books and a number of pieces in the New York Review of Books, New York Times and elsewhere. These texts make it clear that, like many on the centre-left who rose to prominence in the 1990s, Soros’s defining intellectual principle is his internationalism. For Soros, the goal of contemporary human existence is to establish a world defined not by sovereign states, but by a global community whose constituents understand that everyone shares an interest in freedom, equality and prosperity. In his opinion, the creation of such a global open society is the only way to ensure that humanity overcomes the existential challenges of climate change and nuclear proliferation.

Unlike Gates, whose philanthropy focuses mostly on ameliorative projects such as eradicating malaria, Soros truly wants to transform national and international politics and society. Whether or not his vision can survive the wave of antisemitic, Islamophobic and xenophobic rightwing nationalism ascendant in the US and Europe remains to be seen. What is certain is that Soros will spend the remainder of his life attempting to make sure it does.

Soros began his philanthropic activities in 1979, when he “determined after some reflection that I had enough money” and could therefore devote himself to making the world a better place. To do so, he established the Open Society Fund, which quickly became a transnational network of foundations. Though he made some effort at funding academic scholarships for black students in apartheid South Africa, Soros’s primary concern was the communist bloc in eastern Europe; by the end of the 80s, he had opened foundation offices in Hungary, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria and the Soviet Union itself. Like Popper before him, Soros considered the countries of communist eastern Europe to be the ultimate models of closed societies. If he were able to open these regimes, he could demonstrate to the world that money could – in some instances, at least – peacefully overcome oppression without necessitating military intervention or political subversion, the favoured tools of cold war leaders.

Soros set up his first foreign foundation in Hungary in 1984, and his efforts there serve as a model of his activities during this period. Over the course of the decade, he awarded scholarships to Hungarian intellectuals to bring them to the US; provided Xerox machines to libraries and universities; and offered grants to theatres, libraries, intellectuals, artists and experimental schools. In his 1990 book Opening the Soviet System, Soros wrote that he believed his foundation had helped “demolish the monopoly of dogma [in Hungary] by making an alternate source of financing available for cultural and social activities”, which, in his estimation, played a crucial role in producing the internal collapse of communism.

Soros’s use of the word dogma points to two critical elements of his thought: his fierce belief that ideas, more than economics, shape life, and his confidence in humanity’s capacity for progress. According to Soros, the dogmatic mode of thinking that characterised closed societies made it impossible for them to accommodate to the changing vicissitudes of history. Instead, “as actual conditions change”, people in closed societies were forced to abide by an atavistic ideology that was increasingly unpersuasive. When this dogma finally became too obviously disconnected from reality, Soros claimed, a revolution that overturned the closed society usually occurred. By contrast, open societies were dynamic and able to correct course whenever their dogmas strayed too far from reality.

As he witnessed the Soviet empire’s downfall between 1989 and 1991, Soros needed to answer a crucial strategic question: now that the closed societies of eastern Europe were opening, what was his foundation to do? On the eve of the Soviet Union’s dissolution, Soros published an updated version of Opening the Soviet System, titled Underwriting Democracy, which revealed his new strategy: he would dedicate himself to building permanent institutions that would sustain the ideas that motivated anticommunist revolutions, while modelling the practices of open society for the liberated peoples of eastern Europe. The most important of these was Central European University (CEU), which opened in Budapest in 1991. Funded by Soros, CEU was intended to serve as the wellspring for a new, transnational, European world – and the training ground for a new, transnational, European elite.

How could Soros ensure that newly opened societies would remain free? Soros had come of age in the era of the Marshall Plan, and experienced American largesse firsthand in postwar London. To him, this experience showed that weakened and exhausted societies could not be rehabilitated without a substantial investment of foreign aid, which would alleviate extreme conditions and provide the minimum material base that would enable the right ideas about democracy and capitalism to flourish.

For this reason, in the late 80s and early 90s Soros repeatedly argued that “only the deus ex machina of western assistance” could make the eastern bloc permanently democratic. “People who have been living in a totalitarian system all their lives,” he claimed, “need outside assistance to turn their aspirations into reality.” Soros insisted that the US and western Europe give the countries of eastern Europe a substantial amount of pecuniary aid, provide them with access to the European Common Market, and promote cultural and educational ties between the west and the east “that befit a pluralistic society”. Once accomplished, Soros avowed, western Europe must welcome eastern Europe into the European community, which would prevent the continent’s future repartitioning.

Soros’s prescient pleas went unheeded. From the 1990s on, he has attributed the emergence of kleptocracy and hypernationalism in the former eastern bloc to the west’s lack of vision and political will during this crucial moment. “Democracies,” he lamented in 1995, seem to “suffer from a deficiency of values … [and] are notoriously unwilling to take any pain when their vital self-interests are not directly threatened.” For Soros, the west had failed in an epochal task, and in so doing had revealed its shortsightedness and fecklessness.

But it was more than a lack of political will that constrained the west during this moment. In the era of “shock therapy”, western capital did flock to eastern Europe – but this capital was invested mostly in private industry, as opposed to democratic institutions or grassroots community-building, which helped the kleptocrats and anti-democrats seize and maintain power. Soros had identified a key problem but was unable to appreciate how the very logic of capitalism, which stressed profit above all, would necessarily undermine his democratic project. He remained too wedded to the system he had conquered.

In the wake of the cold war, Soros dedicated himself to exploring the international problems that prevented the realisation of a global open society. After the 1997 Asian financial crisis, in which a currency collapse in south-east Asia engendered a world economic downturn, Soros wrote books addressing the two major threats he believed beset open society: hyperglobalisation and market fundamentalism, both of which had become hegemonic after communism’s collapse.

Soros argued that the history of the post-cold war world, as well as his personal experiences as one of international finance’s most successful traders, demonstrated that unregulated global capitalism undermined open society in three distinct ways. First, because capital could move anywhere to avoid taxation, western nations were deprived of the finances they needed to provide citizens with public goods. Second, because international lenders were not subject to much regulation, they often engaged in “unsound lending practices” that threatened financial stability. Finally, because these realities increased domestic and international inequality, Soros feared they would encourage people to commit unspecified “acts of desperation” that could damage the global system’s viability.

Soros saw, far earlier than most of his fellow centre-leftists, the problems at the heart of the financialised and deregulated “new economy” of the 1990s and 2000s. More than any of his liberal peers, he recognised that embracing the most extreme forms of its capitalist ideology might lead the US to promote policies and practices that undermined its democracy and threatened stability both at home and abroad.

In Soros’s opinion, the only way to save capitalism from itself was to establish a “global system of political decision-making” that heavily regulated international finance. Yet as early as 1998, Soros acknowledged that the US was the primary opponent of global institutions; by this point in time, Americans had refused to join the International Court of Justice; had declined to sign the Ottawa treaty on banning landmines; and had unilaterally imposed economic sanctions when and where they saw fit. Still, Soros hoped that, somehow, American policymakers would accept that, for their own best interests, they needed to lead a coalition of democracies dedicated to “promoting the development of open societies [and] strengthening international law and the institutions needed for a global open society”.

But Soros had no programme for how to modify American elites’ increasing hostility to forms of internationalism that did not serve their own military might or provide them with direct and visible economic benefits. This was a significant gap in Soros’s thought, especially given his insistence on the primacy of ideas in engendering historical change. Instead of thinking through this problem, however, he simply declared that “change would have to begin with a change of attitudes, which would be gradually translated into a change of policies”. Soros’s status as a member of the hyper-elite and his belief that, for all its hiccups, history was headed in the right direction made him unable to consider fully the ideological obstacles that stood in the way of his internationalism.

The George W Bush administration’s militarist response to the attacks of September 11 compelled Soros to shift his attention from economics to politics. Everything about the Bush administration’s ideology was anathema to Soros. As Soros declared in his 2004 The Bubble of American Supremacy, Bush and his coterie embraced “a crude form of social Darwinism” that assumed that “life is a struggle for survival, and we must rely mainly on the use of force to survive”. Whereas before September 11, “the excesses of [this] false ideology were kept within bounds by the normal functioning of our democracy”, after it Bush “deliberately fostered the fear that has gripped the country” to silence opposition and win support for a counterproductive policy of militaristic unilateralism. To Soros, assertions such as “either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists” eerily echoed the rhetoric of the Nazis and Soviets, which he hoped to have left behind in Europe. Soros worried, wisely, that Bush would lead the nation into “a permanent state of war” characterised by foreign intervention and domestic oppression. The president was thus not only a threat to world peace, but also to the very idea of open society.

Nevertheless, Soros was confident that Bush’s “extremist ideology” did not correspond “to the beliefs and values of the majority of Americans”, and he expected that John Kerry would win the 2004 presidential election. Kerry’s victory, Soros anticipated, would spur “a profound reconsideration of America’s role in the world” that would lead citizens to reject unilateralism and embrace international cooperation.

But Kerry did not win, which forced the philanthropist to question, for the first time, ordinary Americans’ political acumen. After the 2004 election, Soros underwent something like a crisis of faith. In his 2006 book The Age of Fallibility, Soros attributed Bush’s re-election to the fact that the US was “a ‘feel-good’ society unwilling to face unpleasant reality”. Americans, Soros avowed, would rather be “grievously misled by the Bush administration” than confront the failures of Afghanistan, Iraq and the war on terror head-on. Because they were influenced by market fundamentalism and its obsession with “success”, Soros continued, Americans were eager to accept politicians’ claims that the nation could win something as absurd as a war on terror.

Bush’s victory convinced Soros that the US would survive as an open society only if Americans began to acknowledge “that the truth matters”; otherwise, they would continue to support the war on terror and its concomitant horrors. How Soros could change American minds, though, remained unclear.

The financial crisis of 2007-2008 encouraged Soros to refocus on economics. The collapse did not surprise him; he considered it the predictable consequence of market fundamentalism. Rather, it convinced him that the world was about to witness, as he declared in his 2008 book The New Paradigm for Financial Markets, “the end of a long period of relative stability based on the US as the dominant power and the dollar as the main international reserve currency”.

Anticipating American decline, Soros started to place his hopes for a global open society on the European Union, despite his earlier anger at the union’s members for failing to fully welcome eastern Europe in the 90s. Though he admitted that the EU had serious problems, it was nevertheless an organisation in which nations voluntarily “agreed to a limited delegation of sovereignty” for the common European good. It thus provided a regional model for a world order based on the principles of open society.

Soros’s hopes in the EU, however, were quickly dashed by three crises that undercut the union’s stability: the ever-deepening international recession, the refugee crisis, and Vladimir Putin’s revanchist assault on norms and international law. While Soros believed western nations could theoretically mitigate these crises, he concluded that, in a repetition of the failures of the post-Soviet period, they were unlikely to band together to do so. In the last 10 years, Soros has been disappointed by the facts that the west refused to forgive Greece’s debt; failed to develop a common refugee policy; and would not consider augmenting sanctions on Russia with the material and financial support Ukraine required to defend itself after Putin’s 2014 annexation of Crimea. He was further disturbed that many nations in the EU, from the UK to Poland, witnessed the re-emergence of a rightwing ethnonationalism thought lost to history. Once Britain voted to leave the union in 2016, he became convinced that “the disintegration of the EU [was] practically irreversible”. The EU did not serve as the model Soros hoped it would.

Soros experienced firsthand the racialised authoritarianism that in the last decade has threatened not only the EU, but democracy in Europe generally. Since 2010, the philanthropist has repeatedly sparred with Viktor Orbán, the authoritarian, anti-immigrant prime minister of Hungary. Recently, Soros accused Orbán of “trying to re-establish the kind of sham democracy that prevailed [in Hungary] in the period between the first and second world wars”. In his successful re-election campaign earlier this year, Orbán spent much of his time on the campaign trail demonising Soros, playing on antisemitic tropes and claiming that Soros was secretly plotting to send millions of immigrants to Hungary. Orbán has also threatened the Central European University – which his government derisively refers to as “the Soros university” – with closure, and last month parliament passed new anti-immigration legislation known as the “Stop Soros” laws.

But while Orbán threatens Hungary’s open society, it is Donald Trump who threatens the open society writ large. Soros has attributed Trump’s victory to the deleterious effects market fundamentalism and the Great Recession had on American society. In a December 2016 op-ed, Soros argued that Americans voted for Trump, “a con artist and would-be dictator”, because “elected leaders failed to meet voters’ legitimate expectations and aspirations [and] this failure led electorates to become disenchanted with the prevailing versions of democracy and capitalism”.

Instead of fairly distributing the wealth created by globalisation, Soros argued, capitalism’s “winners” failed to “compensate the losers”, which led to a drastic increase in domestic inequality – and anger. Though Soros believed that the US’s “Constitution and institutions … are strong enough to resist the excesses of the executive branch”, he worried that Trump would form alliances with Putin, Orbán and other authoritarians, which would make it near-impossible to build a global open society. In Hungary, the US and many of the parts of the world that have attracted Soros’s attention and investment, it is clear that his project has stalled.

Soros’s path ahead is unclear. On one hand, some of Soros’s latest actions suggest he has moved in a left-wing direction, particularly in the areas of criminal justice reform and refugee aid. He recently created a fund to assist the campaign of Larry Krasner, the radical Philadelphia district attorney, and backed three California district-attorney candidates similarly devoted to prosecutorial reform. He has also invested $500m to alleviate the global refugee crisis.

On the other hand, some of his behaviour indicates that Soros remains committed to a traditional Democratic party ill-equipped to address the problems that define our moment of crisis. During the 2016 Democratic primary race, he was an avowed supporter of Hillary Clinton. And recently, he lambasted potential Democratic presidential candidate Kirsten Gillibrand for urging Al Franken to resign due to his sexual harassment of the radio host Leeann Tweeden. If Soros continues to fund truly progressive projects, he will make a substantial contribution to the open society; but if he decides to defend banal Democrats, he will contribute to the ongoing degradation of American public life.

Throughout his career, Soros has made a number of wise and exciting interventions. From a democratic perspective, though, this single wealthy person’s ability to shape public affairs is catastrophic. Soros himself has recognised that “the connection between capitalism and democracy is tenuous at best”. The problem for billionaires like him is what they do with this information. The open society envisions a world in which everyone recognises each other’s humanity and engages each other as equals. If most people are scraping for the last pieces of an ever-shrinking pie, however, it is difficult to imagine how we can build the world in which Soros – and, indeed, many of us – would wish to live. Presently, Soros’s cosmopolitan dreams remain exactly that. The question is why, and the answer might very well be that the open society is only possible in a world where no one – whether Soros, or Gates, or DeVos, or Zuckerberg, or Buffett, or Musk, or Bezos – is allowed to become as rich as he has.

Wednesday, 20 June 2018

Democratising the knowledge of Economics - What happens when ordinary people learn economics?

In a makeshift classroom, nine lay people are battling some of the greatest economists of all time – and they appear to be winning. Just watch what happens to David Ricardo, the 18th-century father of our free-trade system. In best BBC voice, one of the group reads out Ricardo’s words: “Economics studies how the produce of the Earth is distributed.”

Not good enough, says another, Brigitte Lechner. Shouldn’t economists study how to meet basic needs? “We all need a roof over our heads, we all need to survive.” Nor does the Earth belong solely to humans. Her judgment is brisk. “Ricardo was talking tosh.”

So much laughter rings out of this room that the folk outside must wonder what’s going on. They’ve been told this is an economics course – and participants on those don’t normally dissolve into giggles.

Inside, Pat Bhatt chimes in: “Everything you see around you comes from nature. That’s the basis of everything. Economics is the wrong word. It should be … ecolo-mics.”

Ooohs and aaahs. “Very clever!” beams the facilitator Nicola Headlam and scribbles it down on the flipboard.

“I invented it,” says Bhatt.

“My work here is done,” replies Headlam. “I’ll get my coat.”

Some days, democracy looks like a bashed-up ballot box. Some days, it looks like a furious demo. But on this sun-splashed weekday morning, democracy looks like this low-ceilinged meeting room in a converted church, slap bang in the middle of the road that runs from Manchester to Stockport.

None of the “students” have ever picked up an economics textbook. At a guess, most would be either stumped or sedated by the Financial Times. Yet here they are, starting a crash course in something that to them is a mystery. The majority are retired, having worked their entire lives. But when asked how many of them feel some control over the economy, not one raises a hand. So who is in charge?

“Journalists – who are paid by rich people.”

Amid all the humour pokes a truth. For this group, economics is something that’s done to them, by people sitting far away in Westminster or the City. They bear the brunt of spending cuts; they struggle with the rottenness of Northern Rail and they see neighbours sinking into debt – and they have no decent account as to why. They have been bashed over the head again and again, and not even been shown the offending shovel.

Over in the corner sits Sue O’Connor, who today comes “sponsored by Visa!” Another gentle joke that masks the debtor’s panic of having her disability benefit hacked back. Cancer meant she lost all her income and wound up in sheltered housing. Now 64, she suffers severe arthritis, yet her Motability caris about to be taken away.

While at a secondary modern, her class was judged too thick to learn any maths. Partly because the teenager wasn’t taught to count, the grey-haired woman still feels she doesn’t count. “Information is power,” she tells the group. “If I can learn in this class, maybe others will listen to me.”

More confident is 70-year-old “raging feminist” Lechner. “The economy is a system, right?” she says. “I understand systems like patriarchy and how it’s set so certain people get hurt … and I want to know how the rules of the economy are set.”

Headlam nods: “Somehow, someone, somewhere made these rules up. They aren’t laws of nature.” And they determine “who’s got what and where and why”.

‘Short of paying nine grand a year for a degree, how else are laypeople meant to find out about the most potent social science of all?’ A flyer for the course. Photograph: Christopher Thomond for the Guardian

That tearing sound you can hear is the veil that normally partitions economics from society and politics.

Up till 2008, someone like O’Connor would have been told over and over that if she’d failed to get ahead it was her fault, not the system’s. She’d just not followed the rules. Then came the financial crisis, which turned into a crisis of economics.

When the Queen famously asked why no economist saw the crash coming, she cut to the heart of the matter: perhaps those who wrote the economy’s laws and policed their observance weren’t so qualified after all. And while some practitioners claim that theirs is a semi-science, all prescriptions to revive the economy – from George Osborne’s historic austerity to the hundreds of billions doled out to asset-owners by the Bank of England – underline how it’s fundamentally political. By the time Michael Gove remarked in the Brexit campaign that “people in this country have had enough of experts”, he was picking a squelchy-soft target.

One of the biggest battles over economics kicked off just up the road from this community centre. At the University of Manchester in 2013, economics undergraduates – tired of memorising abstract models while the eurozone burned – linked up with students from around the world to demand their economics curriculum be changed. Nothing beyond the orthodoxy of free-market economics was being taught; no conflicting global developments, nothing of its critics such as Keynes or Marx, despite their contemporary relevance. Thus began an epic, and epically imbalanced, fight of a bunch of teenagers taking on the very professors marking their exam papers.

Student passions usually fizzle out faster than you can say “snakebite and black”, yet a half decade on, the struggle to prise open economics has got broader. Those ardent undergraduates propping up the union bar are now civil servants pushing for change in government economics; or they’re directing charities such as Economy, which is putting on this crash course in Levenshulme. The aim is to nail the format, then do 15 courses next year, partnering with housing associations, local authorities and others across the UK.

As you might expect from the first session of the first course, this morning’s proceedings betray some nerves. In an ordinary jacket and denim skirt, Headlam tells the class: “We had no idea if you would come.” Unlike the brogue-wearing professoriat, she and her co-facilitator Anne Hines give no sense that they come from a distant planet. Tomorrow morning, former pharmacist Hines sits her own economics exam for an Open University degree course while Headlam, even with her doctorate, describes her academic career as making “target practice for the elite institutions”.

‘Levenshulme is supposed to be gentrifying.’ Photograph: Christopher Thomond for the Guardian

The pair are giving their time for free, and attendees don’t pay a penny. Economy’s Clare Birkett put together the course and organised the pilots on a part-time wage. All five courses, each lasting up to two months and educating anywhere between 50 and 80 people, will together cost little more than the tuition fees for one solitary economics degree.

A few academic economists will ask what authority a bunch of amateurs have, but Birkett has prepared her fighting talk: “If they say, ‘How dare you talk about this?’, I’ll say, ‘Why shouldn’t I? I’ve put in the work, I’ve studied these things. This stuff belongs to all of us.’”

Short of paying nine grand a year for a degree, how else are lay people meant to find out about the most potent social science of all? The internet is full of blind alleys, while even public lectures within universities typically assume some prior knowledge. Given how some economists rage that they’re not listened to enough on issues such as Brexit, it’s notable how little they actually engage with the public (one excellent exception is the annual Bristol Festival of Economics).

Not so long ago, a Levenshulme resident could learn economics – or any number of other subjects – through the adult evening classes offered by the University of Manchester. The extramural programme stretched as far afield as Wigan and Burnley, and by the 1970s employed more than 30 academic staff. Then followed decades of cuts, until the entire department was shut down in 2006.

Which makes economics the humpty-dumpty subject: trust in it is thoroughly broken, yet the public lack the basic tools to put the discipline back together again in a form that reflects their needs. A YouGov survey in 2015 found that more than 60% of respondents did not even know the definition of GDP (gross domestic product) – that staple of BBC bulletins and Westminster debates.

To make the economy more democratic, as everyone from Theresa May to Jeremy Corbyn proposes, we need to democratise knowledge of economics. That’s a truth now cottoned on to by organisations as disparate as the Bank of England and Momentum.

‘Everyone here brings their own lived experience of economics.’ Photograph: Christopher Thomond for the Guardian

Those doing the Levenshulme crash course don’t look like your typical seminar room attendees. Not only are they decades older; all but one is a women. The average undergraduate economics course, according to the Royal Economic Society, is about 67% male and 25% privately educated(compared with 7% of the population). After the class, a charity van pulls up outside, offering three bags of short-dated food for £6. Several “students” collect their groceries for the week.

Everyone here brings their own lived experience of economics. In her motorised wheelchair, Joanne Wilcock notes how “everything is much more expensive when you’re disabled”. Bang on, yet you hardly ever read that in an article on the latest inflation figures. Bhatt knows that Levenshulme is supposed to be gentrifying – “fancy cars, flash weddings” – but notices his neighbours can’t afford to do up their own houses. “All fur coat and no knickers!” he concludes, and the room cracks up.

And if you’re expecting them to trot out the usual left-itudes about fixing the economy, you’re wrong. A discussion about Northern Rail does produce calls for nationalisation – but also arguments as to how it should be turned into a co-op, or run by an arms-length organisation of technocrats.Q&A

Share your storiesShow

Lechner starts on about “citizen scientists” – amateurs who conduct their own experiments – and casts an eye around the room. “Why can’t we be citizen economists?”

That may be the most radical suggestion of the day, because it cuts directly against how both right and left usually do their business. In 1894, the year before cofounding the London School of Economics, Fabian Beatrice Webb confided to her diary: “We have little faith in the ‘average sensual man’. We do not believe that he can do more than describe his grievances, we do not think he can prescribe his remedies … we wish to introduce into politics the professional expert.”

That impulse may now be dressed up in polite euphemism – but it lives on. “So many thinktanks and MPs come up with good ideas to change our economy, but they’re all stuck in their political bubble,” says the head of Economy, Joe Earle. “Ordinary people barely get a say in the thing that rules their lives.”

Contrast that with this class and its polite horizontalism, where no one is presumed to be a total expert and everyone is treated as if they have something valuable to say. It is the seeds of that ferment described by Hilary Wainwright in her recent book, A New Politics from the Left.

‘Aklima Akhter only came to this country in 2013.’ Photograph: Christopher Thomond for the Guardian

Drawing on her experience of feminist and workers’ self-organisation, she writes: “Rebel movements shared and developed their own kinds of knowledge, via practice and through debate and deliberation, and on to producing new ideas and the basis of new institutions. Authority, once it has been confidently questioned by those on whose obedience it depends, crumbles in ways that make it difficult to put back together again.”

At the end of the class, each participant tells the rest the best thing they have learned. There’s a pause when it gets to Aklima Akhter, who only came to this country in 2013 and has been sitting so benignly quiet in her white headscarf. She starts haltingly: “It is difficult for me, you know … the subject, the language.”

All around her are faces pursed in little moues of encouragement, but then Akhter speeds up with fluency. “But my favourite word was ‘nationalisation’. Because when things are privatised it is the rich who get all the benefit.” And for once in this room, no one is laughing.

Sunday, 29 October 2017

Dons, donors and the murky business of funding universities

The University of Oxford is in constant need of money — and it takes an approach to raising it that oscillates between the severe and the relaxed. Those familiar with its procedures say many would-be donors have been turned away. No names are given, outside of senior common room gossip. “Oxford doesn’t need to compromise,” says Sir Anthony Seldon, vice-chancellor of the independent Buckingham University. “People want to be associated with it.” But that confident sense that the great universities will do the right thing has been called into question by a Swedish academic who has thrown down the gauntlet to one of Oxford’s most prominent donors.

Thursday, 25 May 2017

London School of Economics - Shame on you

It is a university that prides itself on being a forum for debate about social injustice and inequality. The London School of Economics was founded by Fabian socialists at the end of the 19th century: they believed education was key to liberating society from social ills.

Last week I was due to attend a debate at the LSE on the expansion of secondary moderns (which is what selection in education really means). At the request of cleaners on strike over their terms and conditions, I withdrew at the last minute. And here is the perverse truth: well-paid speakers will turn up at this prestigious institution to debate the great injustices of modern Britain. Then in come the cleaners – all from migrant or minority backgrounds – to clear up, victims of some of the very injustices that have just been debated.

Like most universities, LSE outsourced its cleaners years ago. It’s cheaper, you see, because the cleaners can then be employed with worse terms and conditions than in-house staff. In this way a university with a multimillion-pound budget can deviously save money on those who clean the libraries, the lecture halls, the offices.

An in-house LSE worker has up to 41 days’ paid leave, six months’ fully paid sick pay, and good maternity pay and pension rights. Cleaners, on the other hand, have the statutory minimum. If they fall ill, they are paid nothing for the first three days, then just £17.87 a day. For a cleaner paid £9.75 an hour – living in one of the world’s most expensive cities – that’s simply not an option. “They can’t afford to be sick,” says Petros Elia, general secretary of the United Voices of the World (UVW) union. Cleaners turn up ill to work instead.

No wonder they describe themselves as “second-class”, “third-class”, or “no-class” workers. The response of LSE’s management is a sobering indictment of industrial relations in a society in which the employers have the whip hand. Cleaners and their supporters have been threatened with arrests and injunctions. “LSE’s mottos is ‘to know the causes of things’,” says Michael Etheridge, the Unison branch secretary, “and yet on the issue of outsourcing it has, as an institution, been wholly ignorant.”

That these cleaners have stood up for themselves – in the face of such hostility – is courageous, and an inspiring precedent for other workers in low-paid, insecure Britain. They’ve come from a variety of different countries; some have only worked at LSE for a few months. But they have organised, and thrown themselves into a determined struggle that now has the university authorities on the run.

Rattled, the LSE has been forced to offer concessions: beginning with 10 days’ full sick pay, then 15, then 20. But UVW and Unison – which represents some of the other cleaners – are clear. This is not a strike simply about improved conditions: it is about being treated the same as other workers. Only parity will do. Unison has been offered a package of improvements, including sick pay of up to 65 days and four weeks of additional maternity pay, and a pledge to work “to reach full parity … in the near future”. But continued pressure on LSE to accept the cleaners’ demands is clearly necessary.

It is a saga that tells many stories about modern Britain. It’s about how, disproportionately, some of the lowest paid and most insecure work is done by migrants and minorities. It’s about a race to the bottom in terms and conditions. It’s about how the law is rigged in favour of bosses. But it’s also about how – with determination and organisation – workers can indeed win.

Mildred Simpson was born in Jamaica and moved to Britain in 1989: she’s worked at the LSE for 16 years. A few years ago she was made a supervisor: back then, there were 25 supervisors, but the number has been slashed to 13. For no extra pay, she is expected to do the jobs of two people. This, for her, is a fight for equality. “We’re doing all the dirty work while they’re drinking their champagne and drinking their coffee,” she says. But she has a message to other workers too. “Fight as well as us as much as you can, for your rights, for pensions, for better working conditions, to be recognised.”

Britain’s universities grant their management lavish salaries: the Former LSE director Craig Calhoun was on a salary package of £381,000 a year and spent tens of thousands on overseas trips. It’s not just cleaners who are mistreated. Academia is becoming increasingly casualised and insecure. At Birmingham University, for instance, a shocking 70% of staff are on insecure contracts. Academics are overworked, struggling with bureaucracy, and often lacking the basic security of knowing how many hours they’re working each week.

Unions have been dramatically weakened in Britain. That has fed into a general sense that injustice is permanent, a fact of life like a weather system, rather than the consequence of human decisions. If there is no apparent collective means available to overcome injustice, then inevitably we become resigned. But if some marginalised, hitherto voiceless cleaners can put one of the world’s most prestigious universities on the backfoot, they set an example to others. This is a country that has endured the longest squeeze in wages for generations, while wealth at the top and in the boardroom has boomed; where our workforce is increasingly stripped of security and fundamental rights. That might be the current direction of travel, but it can be changed. And those cleaners at LSE show how.

Sunday, 6 December 2015

The tyranny of ‘Comrade Bala’

Parvathi Menon in The Hindu

ReutersAravindan Balakrishnan, who has been found guilty of offences, including cruelty to a child, false imprisonment and rape and indecent assault.

The details of the story Aravindan Balakrishnan – the 73 year old leader of a bizzare Maoist cult who was yesterday sentenced to life imprisonment for rape, sexual assaults, cruelty to a child, and false imprisonment – are being unraveled in the British media after two members of his collective broke the silence and secrecy that bound them for the last several decades.

The first is his 30-year old daughter, with the pseudonym “Fran” who was born into captivity ; and the second is Josephine Herival, the woman who helped his daughter escape but still insists that Mr. Balakrishnan is innocent.

In the time between his arrival in the United Kingdom in the 1970s as a young student from Malaysia come to study at the London School of Economics – a handsome young bespectacled man in his photograph – to the wizened old man shuffling to the courts accompanied by his wife, as TV images show him today, Mr. Balakrishnan created an alternate world for a group of people who came under his tyrannical control.

The Brixton-based Workers’ Institute of Marxism-Leninism Mao Zedong Thought established by Mr. Balakrishnan, was one of the many splinter groups that emerged in the radicalism of the late 1960s and 1970s in Britain. The bright, charismatic and articulate revolutionary attracted followers, including Sian Davies, Fran’s mother. The group set up office in Brixton, and in 1978 it was raided by the police in search of drugs that were not found. Several of them were arrested, including Mr. Balakrishnan. After this a number of people left and a remaining core slowly shut themselves out from the outside world and retreated into a small cult that revolved around a single leader who became increasingly crazed and despotic, Comrade Bala.

For these people, all women, the leader apparently imposed stringent rules about what they could and could not do or say. Comrade Bala frequently invoked the wrath of a universe-controlling machine called Jackie that would wreak hell and damnation on them if they fell out of step. In 1983, Comrade Bala and Ms. Davies had a daughter, but never revealed the fact to her. In unclear circumstances, in 1996 Ms. Davies fell from the bathroom window of a commune house after apparently becoming mentally ill.

Fran was 13 at the time. She had never been sent to school and was taught to read and write at home, becoming as she grew up a keen diarist. Much of what is known about life in the commune is documented in it. She described herself as a “fly caught in a web” and a “bird in a cage with clipped wings” in an interview to the BBC, in which her face was not shown. Her father used to regularly abuse and beat her and the other women, and tell the little girl who longed to go out and play on the swings with other children, that lightning would strike her dead, or she would spontaneously combust.

Fran made an unsuccessful attempt to escape when she was 22. It was in October 2013 that an opportunity presented itself again. Learning of a charity that rescued women, Fran, who believed she was desperately ill with diabetes, and another commune inmate, Josephine Herival, called the charity, which rescued her. The lid on the commune and its activities was lifted.

Clearly, however, Comrade Bala’s hold continues. Speaking to Channel 4 on Friday, Josephine Herival, insisted he was innocent. “I know Aravindan Balakrishnan…he is such a good person. Anyone who knows him will say the same thing.” She says that the evidence given against him in the court are “outrageous allegations.”

Fran is integrated herself into society well, according to her carers, starting formal studies and even becoming a member of the Labour Party – living life that was denied her for 30 years.

Monday, 12 October 2015

Don’t let the Nobel prize fool you. Economics is not a science

Joris Luyendijk in The Guardian

Business as usual. That will be the implicit message when the Sveriges Riksbank announces this year’s winner of the “Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel”, to give it its full title. Seven years ago this autumn, practically the entire mainstream economics profession was caught off guard by the global financial crash and the “worst panic since the 1930s” that followed. And yet on Monday the glorification of economics as a scientific field on a par with physics, chemistry and medicine will continue.

The problem is not so much that there is a Nobel prize in economics, but that there are no equivalent prizes in psychology, sociology, anthropology. Economics, this seems to say, is not a social science but an exact one, like physics or chemistry – a distinction that not only encourages hubris among economists but also changes the way we think about the economy.

A Nobel prize in economics implies that the human world operates much like the physical world: that it can be described and understood in neutral terms, and that it lends itself to modelling, like chemical reactions or the movement of the stars. It creates the impression that economists are not in the business of constructing inherently imperfect theories, but of discovering timeless truths.

Economist Sir Richard Blundell among Nobel prize frontrunners

To illustrate just how dangerous that kind of belief can be, one only need to consider the fate of Long-Term Capital Management, a hedge fund set up by, among others, the economists Myron Scholes and Robert Merton in 1994. With their work on derivatives, Scholes and Merton seemed to have hit on a formula that yielded a safe but lucrative trading strategy. In 1997 they were awarded the Nobel prize. A year later, Long-Term Capital Management lost $4.6bn (£3bn)in less than four months; a bailout was required to avert the threat to the global financial system. Markets, it seemed, didn’t always behave like scientific models.

In the decade that followed, the same over-confidence in the power and wisdom of financial models bred a disastrous culture of complacency, ending in the 2008 crash. Why should bankers ask themselves if a lucrative new complex financial product is safe when the models tell them it is? Why give regulators real power when models can do their work for them?

Many economists seem to have come to think of their field in scientific terms: a body of incrementally growing objective knowledge. Over the past decades mainstream economics in universities has become increasingly mathematical, focusing on complex statistical analyses and modelling to the detriment of the observation of reality.

Consider this throwaway line from the former top regulator and London School of Economics director Howard Davies in his 2010 book The Financial Crisis: Who Is to Blame?: “There is a lack of real-life research on trading floors themselves.” To which one might say: well, yes, so how about doing something about that? After all, Davies was at the time heading what is probably the most prestigious institution for economics research in Europe, located a stone’s throw away from the banks that blew up.

All those banks have “structured products approval committees”, where a team of banking staff sits down to decide whether their bank should adopt a particular new complex financial product. If economics were a social science like sociology or anthropology, practitioners would set about interviewing those committee members, scrutinising the meetings’ minutes and trying to observe as many meetings as possible. That is how the kind of fieldwork-based, “qualitative” social sciences, which economists like to discard as “soft” and unscientific, operate. It is true that this approach, too, comes with serious methodological caveats, such as verifiability, selection bias or observer bias. The difference is that other social sciences are open about these limitations, arguing that, while human knowledge about humans is fundamentally different from human knowledge about the natural world, those imperfect observations are extremely important to make.

Compare that humility to that of former central banker Alan Greenspan, one of the architects of the deregulation of finance, and a great believer in models. After the crash hit, Greenspan appeared before a congressional committee in the US to explain himself. “I made a mistake in presuming that the self-interests of organisations, specifically banks and others, were such that they were best capable of protecting their own shareholders and their equity in the firms,” said the man whom fellow economists used to celebrate as “the maestro”.

Nobel Prizes in science: strictly a man’s game?

In other words, Greenspan had been unable to imagine that bankers would run their own bank into the ground. Had the maestro read the tiny pile of books by financial anthropologists he may have found it easier to imagine such behaviour. Then he would have known that over past decades banks had adopted a “zero job security” hire-and-fire culture, breeding a “zero-loyalty” mentality that can be summarised as: “If you can be out of the door in five minutes, your horizon becomes five minutes.”

While this was apparently new to Greenspan it was not to anthropologist Karen Ho, who did years of fieldwork at a Wall Street bank. Her book Liquidated emphasises the pivotal role of zero job security at Wall Street (the same system governs the City of London). The financial sociologist Vincent Lépinay’s Codes of Finance, a book about the division in a French bank for complex financial products, describes in convincing detail how institutional memory suffers when people switch jobs frequently and at short notice.

Perhaps the most pernicious effect of the status of economics in public life has been the hegemony of technocratic thinking. Political questions about how to run society have come to be framed as technical issues, fatally diminishing politics as the arena where society debates means and ends. Take a crucial concept such as gross domestic product. As Ha-Joon Chang makes clear in 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism, the choices about what not to include in GDP (household work, to name one) are highly ideological. The same applies to inflation, since there is nothing neutral about the decision not to give greater weight to the explosion in housing and stock market prices when calculating inflation.

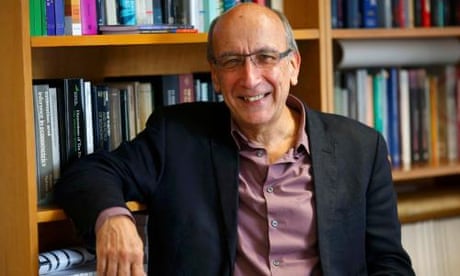

Ha-Joon Chang, pictured at the Hay-on-Wye festival, Wales. Photograph: David Levenson/Getty Images

GDP, inflation and even growth figures are not objective temperature measurements of the economy, no matter how many economists, commentators and politicians like to pretend they are. Much of economics is politics disguised as technocracy – acknowledging this might help open up the space for political debate and change that has been so lacking in the past seven years.

Would it not be extremely useful to take economics down one peg by overhauling the prize to include all social sciences? The Nobel prize for economics is not even a “real” Nobel prize anyway, having only been set up by the Swedish central bank in 1969. In recent years, it may have been awarded to more non-conventional practitioners such as the psychologist Daniel Kahneman. However, Kahneman was still rewarded for his contribution to the science of economics, still putting that field centre stage.

Think of how frequently the Nobel prize for literature elevates little-known writers or poets to the global stage, or how the peace prize stirs up a vital global conversation: Naguib Mahfouz’s Nobel introduced Arab literature to a mass audience, while last year’s prize for Kailash Satyarthi and Malala Yousafzai put the right of all children to an education on the agenda. Nobel prizes in economics, meanwhile, go to “contributions to methods of analysing economic time series with time-varying volatility” (2003) or the “analysis of trade patterns and location of economic activity” (2008).

A revamped social science Nobel prize could play a similar role, feeding the global conversation with new discoveries and insights from across the social sciences, while always emphasising the need for humility in treating knowledge by humans about humans. One good candidate would be the sociologist Zygmunt Bauman, whose writing on the “liquid modernity” of post-utopian capitalism deserves the largest audience possible. Richard Sennett and his work on the “corrosion of character” among workers in today’s economies would be another. Will economists volunteer to share their prestigious prize out of their own acccord? Their own mainstream economic assumptions about human selfishness suggest they will not.