When marketing manager Eliza returned from holiday, she received an email from her boss asking her to arrive at work early the next day. “I instantly feared the worst,” she explains. “I knew the job wasn’t the best fit. I’d had my probation previously extended; there was an expectation of weekend working and post-work drinking that didn’t suit me. I thought he’d used my time off as an opportunity to fire me.”

However, when Eliza arrived at her boss’s office, she wasn’t immediately let go. Instead, she was informed of a company restructure – her job description was being completely rewritten. Someone else would take over her tasks, and she would be expected to work remotely in a new admin role.

In the weeks that followed, Eliza’s professional life became much quieter. Instead of formulating the London-based events agency’s marketing strategy from the office or attending live shows as part of her remit, her main duties now consisted of simply being available between 0900 and 1800, sending the occasional email and completing the odd routine task from home.

Eliza had effectively been frozen out by her employer. Barely a month later, she quit. “It was humiliating – I was made to feel worthless,” she says. “It was the worst experience of my career: I’d rather have been just fired on the spot and paid off than have to go through that.”

There may not always be a good fit between jobs and the workers hired to do them. In these cases, companies and bosses may decide they want the worker to depart. Some may go through formal channels to show employees the door, but others may do what Eliza’s boss did – behave in such a way that the employee chooses to walk away. Methods may vary; bosses may marginalise workers, make their lives difficult or even set them up to fail. This can take place over weeks, but also months and years. Either way, the objective is the same: to show the worker they don’t have a future with the company and encourage them to leave.

In overt cases, this is known as ‘constructive dismissal’: when an employee is forced to leave because the employer created a hostile work environment. The more subtle phenomenon of nudging employees slowly but surely out of the door has recently been dubbed ‘quiet firing’ (the apparent flipside to ‘quiet quitting’, where employees do their job, but no more). Rather than lay off workers, employers choose to be indirect and avoid conflict. But in doing so, they often unintentionally create even greater harm.

The path of least resistance

For myriad reasons, bosses have long tried to nudge workers they perceive as underperforming or being a bad cultural fit out the door. “This has been happening in workplaces for decades,” says Christopher Kayes, professor of management at the George Washington University School of Business, based in Washington, DC.

The tactic means firms and managers can end up saddled with workers they don’t want, leading to managers engaging in behaviours often seen as passive-aggressive

The reasons for this are complex. If workers behave in ways that violate their contracts, for example, companies can terminate their employment. But if bosses simply dislike workers, or see them as middling or mediocre performers, taking action to remove them is more complicated, often requiring lengthy processes involving performance management programmes and multiple warnings.

“Companies are usually reluctant to let a worker go,” says Kayes. Firing leads to an “immediate sense of sides being created” which, at worst, can land the company in court if the worker contests it, potentially generating negative headlines about the working environment. “It’s often easier to simply let the underperforming employee stay in the job than to go through the process of firing and potential litigation.”

Employers often don’t want to expose themselves to risk or conflict, adds Suzanne Horne, partner in employment law at legal firm Paul Hastings, based in London. “Subtly encouraging someone to leave is seen as the easier option. If the employee eventually resigns, it’s the ‘no-fault approach’: severance doesn’t need to be paid, conflict is avoided and both parties are ultimately happy.”

Managing perceived poor performance, working with the employee to improve their output and turning them into a useful resource for the company would be an alternative way to deal with the problem. However, Kayes says bosses are often ill-equipped to do this, whether through a lack of time or training. “Organisations tend to be bad at preparing leaders to take on the responsibilities they’ll need in the job. So, they often find themselves without the resources they need to be effective and deal with employee underperformance.”

In this situation, with firing seen as a last resort and managers unable – or unwilling – to turn the employee into what they want them to be, they often follow the path of least resistance: quiet firing. “Much of it is ultimately an avoidance behaviour and comes down to procrastination: managers in most cases are wanting to avoid having difficult conversations,” points out Kayes. “Ironically, they worry that firing a worker will reflect poorly on them, so they quietly fire them instead.”

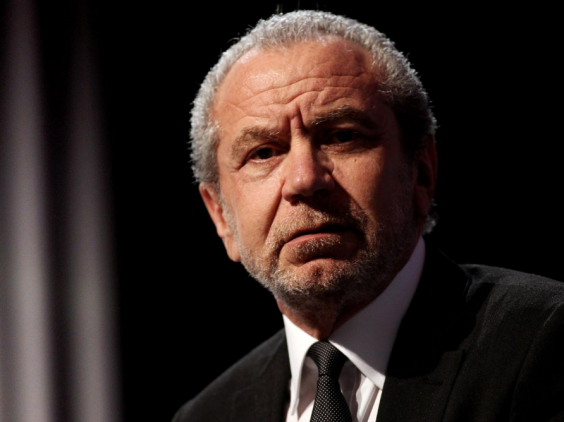

To push out workers, managers may sometimes set up workers to fail with impossible tasks, or take away their jobs altogether (Credit: Getty Images)

Why it often backfires

By engaging in quiet-firing behaviours, managers are likely to be playing the long game. In theory, it’s low risk and minimal effort; the hope is that by withdrawing support, the worker soon realises they don’t have a future at the company and moves elsewhere.

However, this approach can have collateral damage. The tactic means firms and managers can end up saddled with workers they don’t want, leading to managers engaging in behaviours often seen as passive-aggressive, says Kayes. “You stop offering the employee opportunities to advance; you stop inviting them to certain meetings; you stop providing them important work and feedback.”

There is also the risk of creating an ‘us and them’ mentality, potentially harming workers not targeted for quiet firing. “You have the engaged employees, and then those just quietly left there, sometimes without their knowledge,” says Horne. “It doesn’t create an inclusive or high-performance workplace culture.”

Quiet firing can affect a firm’s reputation, too, even if a worker departs without apparent conflict; employees may well share their experience in an online review. “There’s a greater awareness of employment rights today,” says Horne. “People are now more willing to call out workplace issues, especially following the pandemic.”

An employee subtly nudged out the door isn't without legal recourse, either. “If you were to look at each individual aspect of quiet firing, there’s likely nothing serious enough to prove an employer breach of contract,” says Horne. “However, there’s the last-straw doctrine: one final act by the employer which, when added together with past behaviours, can be asserted as constructive dismissal by the employee.”

More immediate though, is the mental-health cost to the worker deemed to be expendable by the employer – but who is never directly informed. “The psychological toll of quiet firing creates a sense of rejection and of being an outcast from their work group. That can have a huge negative impact on a person’s wellbeing,” says Kayes.

Eliza agrees. “I was made to feel worthless and useless being quietly fired,” she says. Now happily employed elsewhere, she’s realised that her experience “was a reflection of having a terrible boss, rather than me”. But other people who experience quiet firing over the longer term, in more insidious ways, may not see things so clearly.

I was made to feel worthless and useless being quietly fired – Eliza

“Over time, an employee may figure out something isn’t right if their one-to-one meetings are always cancelled, their manager never makes time to talk about development and performance or they’re always overlooked for promotion,” says Horne. “They face a daily drip feed of their employer trying to make them resign – it’s absolutely gruelling.”

'A self-fulfilling prophecy'

Quiet firing may be the easiest option on the table for bosses – especially in a remote-work world, where excluding employees is even easier – but it’s not a good solution for firms or workers.

“Employers can end up damaging their business’s morale, productivity and culture while risking litigation proceedings anyway,” says Horne. “For employees, there’s a mental-health impact of feeling excluded, frustrated or angry. They can lose their confidence and it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy: their performance declines even further.”

Fixing it requires better-resourced managers, greater HR support and the acceptance that workplace confrontation is sometimes best. However, the time and cost needed to educate managers on how to better motivate employees and deal with difficult situations means that, realistically, quiet firing may be here to stay. “Training is expensive,” says Kayes. “It takes huge investment and requires leaders to be open to it; an acceptance that they need to ask themselves hard questions.

Human psychology plays its part, too. Ultimately, quiet firing is the avoidance of difficult emotions. “There can be the implication that the manager is being nasty or manipulative when they quietly fire an employee, but there is a person on either side of the table,” says Horne. “And people generally like to avoid hard conversations.”

Eliza is using one name for career-security reasons