The writer, Daniel Susskind in The FT, is the author of ‘Growth: A Reckoning’ and an economist at Oxford university and King’s College London

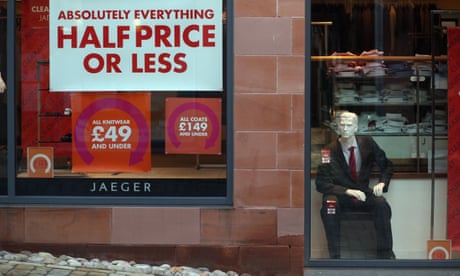

There seem to be few policy problems in Britain that “growth” will not solve. Backlogged and broken public services? We need growth to bolster tax revenues. National debt breaking £1tn for the first time? We need growth to make that sustainable. Rising worklessness and real wages that have not budged for 15 years? We need growth to fire up the labour market.

Growth has become one of those rare things, a policy panacea: promising to benefit almost everyone in society, leaving few problems out of its restorative reach. And for that reason, its pursuit has bent the political spectrum back on itself, with leaders at opposite ends meeting in agreement about its merits. For Sir Keir Starmer, it is the “defining mission” of his government; for Rishi Sunak, it was one of his party’s ill-fated “five priorities”.

The focus on growth is surely right. We need more of it. The challenge is how to create it. Today’s political leaders talk confidently about what is required. But this sense of assuredness is entirely at odds with the little we really know about growth’s causes.

To begin with, the idea that we should pursue growth at all is surprisingly new. Before the 1950s, almost no politicians, policymakers, economists — anyone — talked about it. That changed with the cold war. The US and Soviet Union, each desperate to show that their side was winning the battle of ideologies, furiously competed to outgrow one another.

As political interest took off, economists tumbled over one another in their attempts to look useful, responding — with new stories, models and data — to these practical concerns. “[D]uring the Sixties”, wrote the economist Dennis Mueller, “the growth rate of the ‘growth literature’ far exceeded that of the phenomenon it tried to explain.”

Yet despite all that intellectual firepower, we still lack definitive answers to the question of what causes growth. “The subject has proved elusive”, wrote the economist Elhanan Helpman in 2004, “and many mysteries remain.”

There is an old-fashioned view of productive activity that pictures the economy as purely a material thing. From this perspective, growth is driven by building impressive things that we can all see and touch — faster trains, wider roads, more houses.

However, the little we do know suggests that it does not actually come from the world of tangible things, but rather from the world of intangible ideas; not from guzzling up ever more finite resources — land, people, machines, and so on — but from discovering new ideas that make ever more productive use of those resources. Or, more simply, sustained economic growth comes from relentless technological progress.

These observations — how little we know about growth and the power of ideas in driving it — have important practical implications. The former is a warning against hubris. Political leaders should not claim to have more control over our economic fate than they actually do. After all, if there were a simple lever we could pull for more growth, the problem of economic development would have been solved some time ago.

The latter observation offers us guidance. We cannot simply “build” our way to more prosperity: there are good reasons to build more houses, for instance, but a radical transformation in national growth prospects is unlikely to be one of them. Instead, securing growth will require a relentless focus on the discovery of new ideas, doing all that we can to make Britain the best place in the world to develop and adopt the most powerful new technologies of our time.

Vastly more investment in R&D would be a good place for the new government to start. In the UK, expenditure as a percentage of GDP is stuck at just half of what Israel (the leader in this field) achieves. But we must go further.

During the 20th century, growth came about by providing human beings with ever more education: first basic schooling and then, later on, colleges and universities. For that reason it is known as the human-capital century, a time when a country’s prosperity depended on its willingness to invest in its people.

The current century will be different. New ideas will come less frequently from us and more from the technologies around us. We can already catch a glimpse of what lies ahead: from large companies like Google DeepMind using AlphaFold to solve the protein-folding problem to each of us at our desks using generative AI — from GPT to Dall-E. Whether Britain flourishes or fades in this future will depend on our willingness to invest in these new technologies and the people and institutions behind them. Any serious strategy for growth must start with that fact.