'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label CEO. Show all posts

Showing posts with label CEO. Show all posts

Tuesday, 26 March 2024

Saturday, 27 January 2024

Jürgen Klopp’s departure holds lessons for leaders everywhere

Simon Kuper in The FT

In an era short on admired leaders, Jürgen Klopp has been a rare role model. The German football manager, who announced on Friday that he is resigning at the end of this season after nine years at Liverpool, offers numerous lessons for his counterparts in business and politics.

First, he turned himself into the embodiment of the institution he led. He always presented himself not as a mere technocrat but as somebody who loved Liverpool FC. Having joined the club as an outsider, he worked to understand what it meant to everyone involved in it. In his hugs and emotional sprints along the touchline (and sometimes into the field), the giant with football’s most joyous smile expressed the feelings of every Liverpool fan.

When the club won its first English league title in 30 years in 2020, he said, “I never could have thought it would feel like this, I had no idea,” and cried. He told Liverpool’s supporters: “It is a joy to do it for you.” He probably wasn’t faking it, giving that he has kept up the act practically daily since 2015. He understands that the whole point of professional football is shared communal emotion.

Second, he treated his players and staff as humans, not as mere instruments for his own success. When one staff member was unaware that full-back Andy Robertson would soon become a father for the first time, Klopp asked: “How can you not know that? That is the biggest thing in his life now.”

Klopp wanted to know everything about his players — “who they are, what they believe in, how they’ve reached this point, what drives them, what awaits them when they depart training.” And he meant it: “I don’t pretend I’m interested, I am interested.”

Klopp is often praised as a motivator, but in fact few top-class footballers need motivation. His man-management was more sophisticated than that. His understanding of people helped him find the right words in clear, simple and cliché-free English, his second language. In 2019, after a 3-0 defeat in the first leg of the Champions League semi-final at Barcelona, he bounded smiling into Liverpool’s deflated changing-room shouting, “Boys, boys, boys! We are not the best team in the world. Now you know that. Maybe they are! Who cares? We can still beat the best team in the world. Let’s go again.” Before the return leg at Anfield, he told his players: “Just try. If we can do it, wonderful. If not, then fail in the most beautiful way.”

He was lifting his men while also lifting the pressure: he gave them permission to fail. Instead, in perhaps the most breathtaking match of his tenure, they won 4-0, and went on to clinch the Champions League. His Liverpool lost two other Champions League finals. With a touch more luck, their achievement could have been generational. But even at the leanest moments, all the constituencies that make up a club — owner, players, staff, fans, media — wanted him around. Klopp made ruthless decisions without making enemies.

Another leadership lesson: he could delegate. A football manager today is less autocrat than chief executive, overseeing a staff of dozens. Klopp provided the guiding vision, of a pressing game played at frenzied pace: “It is not serenity football, it is fighting football — that is what I like . . . Rainy day, heavy pitch, everybody is dirty in the face and they go home and can’t play football for the next four weeks.”

He left most of the detail to specialists. For years he outsourced much of his training and match tactics to his assistant, Željko Buvač, whom Klopp called “the brain” of his coaching team.

Klopp was so obviously the leader, an Alpha male blessed with empathy, that he felt secure enough to listen to others and admit error. In 2017, when Liverpool needed a striker, the club’s data analysts lobbied him to sign the Egyptian Mo Salah. Klopp preferred the German forward Julian Brandt. It took time, but eventually Klopp was persuaded to buy Salah. The Egyptian became arguably Liverpool’s most important player. Klopp later apologised to the analysts for his mistake.

In a profession that attracts many megalomaniacs and then places them under inhuman stress, he was rare in never taking himself too seriously. He had views outside football — for leftwing politics, against Brexit — but he rejected the temptation to cast himself as a universal leader. When Covid-19 was spreading in early 2020, and a journalist fished for his views, he said experts should speak, not “people with no knowledge, like me . . . I don’t understand politics, coronavirus . . . I wear a baseball cap and have a bad shave.”

His last leadership lesson: leave at the right time, with dignity. Today he explained his resignation: “I came here as a normal guy. I am still a normal guy, I just don’t live a normal life for too long now. And I don’t want to wait until I am too old to have a normal life, and I need, at least, to give it a try.”

He also admitted fallibility, with a typically well-chosen metaphor: “I am a proper sports car, not the best one, but a pretty good one, can still drive 160, 170, 180 miles per hour, but I am the only one who sees the tank needle is going down.” It was a message to every failed leader currently clinging grimly to power.

Tuesday, 16 June 2015

The menace of the last-wicket stand: Come in, No. 11!

Simon Barnes in Wisden India

It’s time to resurrect the Campaign for Real Number Elevens. We are in danger of losing touch with one of cricket’s most ancient traditions. One of the last Test series in England in which both teams included a classic No. 11 involved India, in 1990. And it was all the more inspiring for the contrast between them.

India had the leg-spinner Narendra Hirwani – a wee sleekit cow’rin tim’rous beastie of a batter, convinced that every ball was an explosive device best negotiated from square leg. In 17 Tests he scored 54 runs at 5.40. During that series, when India required 24 to save the follow-on at Lord’s, Kapil Dev launched Eddie Hemmings for four sixes in a row, rather than trust Hirwani to face a delivery. He was right, too: Hirwani fell first ball next over.

England countered with Devon Malcolm, a fast bowler convinced of his own immortality: a mighty, wide-shouldered swiper who never let his own poor eyesight – in his early days he played in Hank Marvin horn-rims – get in the way of his belief that every ball bowled to him belonged on the far side of the boundary. This approach brought him 236 runs in 40 Tests at 6.05.

But these guys are history. The contemporary No. 11 can bat. It’s not that every clown now wants to play Hamlet; they always did. These days, every clown can play the attendant lord, infinitely capable of swelling a progress, or starting a scene or two as circumstances require. As a result, the fall of the ninth wicket is no longer the signal to put the kettle on. The last-wicket stand used to be one of cricket’s brilliant jokes. Now it’s got serious.

In the First Test at Trent Bridge last summer, the Indian first innings concluded with a last-wicket stand worth 111, between Bhuvneshwar Kumar and Mohammed Shami. These days, though, substantial last-wicket stands come along like the No. 49 bus, and the next arrived one innings later, as Joe Root and Jimmy Anderson put on a Test-record 198; Anderson was disappointed when he got out for 81.

The previous year the Ashes had begun with Australia’s last-wicket stand of 163 – also at Trent Bridge, also a Test record – between Phillip Hughes and Ashton Agar. Agar, the No. 11, was out for 98; it turned out he was a far better batsman than bowler. And, in 2012, Denesh Ramdin and Tino Best hit 143 for the tenth wicket for West Indies at Edgbaston.

So let’s savour a few stats. In last summer’s England–India series, the average tenth-wicket stand was 38, higher than for any series of more than three matches. The previous-best was 33 – for the 2013 Ashes. The last wickets of England and India contributed 499 runs, another record; third, with 432, is the 2013 Ashes. Second and fourth in the list are the 1924-25 and 1894-95 Ashes, outliers from pre-history. The current numbers appear to indicate a trend – and 13 of the 26 last-wicket hundred stands have come this century.

A decent last-wicket stand is less of a surprise than it used to be. But its increasing regularity makes it even more irritating for the fielding side. It’s a combination of free runs and derisive mockery of the opposition. It’s a classic win double: the batting side feels better and better, while the bowling side feels ghastlier and ghastlier. It’s not as if someone has stolen an advantage: it’s more as if God Himself has taken sides.

It’s a time when the team that are more batted against than batting tend to lose their head. They start a bumper war; since these stands usually happen on flat pitches, that tends to be a doomed project. Or they try to get only one batsman out, which means that the man higher up the order can focus freely on scoring runs. And the longer the No. 11 stays in, the more capable he feels about looking after himself, and the more he can take annoying singles.

A terrible feeling gathers in the bowling side: this ought not to be happening. It’s a freak, and it’s freakishly unfair. In truth, it’s a freak no longer. The spectacle of tired bowlers running in on flat pitches to jubilant tailenders while infuriated fielders dive about in vain is becoming one of cricket’s staples.

This can be doubly difficult for the bowling side if the captain is an opening batsman, such as Alastair Cook for England: mentally preparing to bat at the drop of the next wicket, but unable to take that wicket, and unable to think with absolute clarity about how best to do so. It’s captaincy as a classic frustration dream: on a par with running for the train through a sea of treacle, or opening the exam paper and realising you don’t understand the questions, still less know the answers.

It’s not hard to work out how this has come about. Ever since the one-day game became part of cricket, bowlers regularly bat in important match situations. They know that, when it comes to selection between two bowlers of apparently equal merit, the nod goes to the better batsman. Bowlers work at batting. They have nets, they have coaches, they have batting buddies.

Meanwhile, protective equipment, especially the helmet, has made it much easier to be brave against fast bowling, while modern bat technology means that even mis-hits reach the boundary. And if this were not enough to tip things in favour of more and bigger last-wicket stands, the tendency to produce chief executives’ wickets has made these former oddities into statistical certainties. Three of those recent monster stands were at Trent Bridge; their pitch for the India match was rated “poor” by the ICC.

So among the general hilarity of the last-wicket stand – and they are gloriously funny to everyone not bowling or fielding at the time – there is a point that is serious, not to say sinister. It’s not just that tailenders have learned how to bat: it’s that the essential balance between bat and ball has made a significant shift.

It’s easier to bat and score runs than it has been at any time in the history of cricket. The proliferation of huge last-wicket stands indicates that something has gone seriously amiss. Take that England–India game at Trent Bridge. One can be regarded as good fortune. Two looks like misgovernment on a global scale.

It’s time to resurrect the Campaign for Real Number Elevens. We are in danger of losing touch with one of cricket’s most ancient traditions. One of the last Test series in England in which both teams included a classic No. 11 involved India, in 1990. And it was all the more inspiring for the contrast between them.

India had the leg-spinner Narendra Hirwani – a wee sleekit cow’rin tim’rous beastie of a batter, convinced that every ball was an explosive device best negotiated from square leg. In 17 Tests he scored 54 runs at 5.40. During that series, when India required 24 to save the follow-on at Lord’s, Kapil Dev launched Eddie Hemmings for four sixes in a row, rather than trust Hirwani to face a delivery. He was right, too: Hirwani fell first ball next over.

England countered with Devon Malcolm, a fast bowler convinced of his own immortality: a mighty, wide-shouldered swiper who never let his own poor eyesight – in his early days he played in Hank Marvin horn-rims – get in the way of his belief that every ball bowled to him belonged on the far side of the boundary. This approach brought him 236 runs in 40 Tests at 6.05.

But these guys are history. The contemporary No. 11 can bat. It’s not that every clown now wants to play Hamlet; they always did. These days, every clown can play the attendant lord, infinitely capable of swelling a progress, or starting a scene or two as circumstances require. As a result, the fall of the ninth wicket is no longer the signal to put the kettle on. The last-wicket stand used to be one of cricket’s brilliant jokes. Now it’s got serious.

In the First Test at Trent Bridge last summer, the Indian first innings concluded with a last-wicket stand worth 111, between Bhuvneshwar Kumar and Mohammed Shami. These days, though, substantial last-wicket stands come along like the No. 49 bus, and the next arrived one innings later, as Joe Root and Jimmy Anderson put on a Test-record 198; Anderson was disappointed when he got out for 81.

The previous year the Ashes had begun with Australia’s last-wicket stand of 163 – also at Trent Bridge, also a Test record – between Phillip Hughes and Ashton Agar. Agar, the No. 11, was out for 98; it turned out he was a far better batsman than bowler. And, in 2012, Denesh Ramdin and Tino Best hit 143 for the tenth wicket for West Indies at Edgbaston.

So let’s savour a few stats. In last summer’s England–India series, the average tenth-wicket stand was 38, higher than for any series of more than three matches. The previous-best was 33 – for the 2013 Ashes. The last wickets of England and India contributed 499 runs, another record; third, with 432, is the 2013 Ashes. Second and fourth in the list are the 1924-25 and 1894-95 Ashes, outliers from pre-history. The current numbers appear to indicate a trend – and 13 of the 26 last-wicket hundred stands have come this century.

A decent last-wicket stand is less of a surprise than it used to be. But its increasing regularity makes it even more irritating for the fielding side. It’s a combination of free runs and derisive mockery of the opposition. It’s a classic win double: the batting side feels better and better, while the bowling side feels ghastlier and ghastlier. It’s not as if someone has stolen an advantage: it’s more as if God Himself has taken sides.

It’s a time when the team that are more batted against than batting tend to lose their head. They start a bumper war; since these stands usually happen on flat pitches, that tends to be a doomed project. Or they try to get only one batsman out, which means that the man higher up the order can focus freely on scoring runs. And the longer the No. 11 stays in, the more capable he feels about looking after himself, and the more he can take annoying singles.

A terrible feeling gathers in the bowling side: this ought not to be happening. It’s a freak, and it’s freakishly unfair. In truth, it’s a freak no longer. The spectacle of tired bowlers running in on flat pitches to jubilant tailenders while infuriated fielders dive about in vain is becoming one of cricket’s staples.

This can be doubly difficult for the bowling side if the captain is an opening batsman, such as Alastair Cook for England: mentally preparing to bat at the drop of the next wicket, but unable to take that wicket, and unable to think with absolute clarity about how best to do so. It’s captaincy as a classic frustration dream: on a par with running for the train through a sea of treacle, or opening the exam paper and realising you don’t understand the questions, still less know the answers.

It’s not hard to work out how this has come about. Ever since the one-day game became part of cricket, bowlers regularly bat in important match situations. They know that, when it comes to selection between two bowlers of apparently equal merit, the nod goes to the better batsman. Bowlers work at batting. They have nets, they have coaches, they have batting buddies.

Meanwhile, protective equipment, especially the helmet, has made it much easier to be brave against fast bowling, while modern bat technology means that even mis-hits reach the boundary. And if this were not enough to tip things in favour of more and bigger last-wicket stands, the tendency to produce chief executives’ wickets has made these former oddities into statistical certainties. Three of those recent monster stands were at Trent Bridge; their pitch for the India match was rated “poor” by the ICC.

So among the general hilarity of the last-wicket stand – and they are gloriously funny to everyone not bowling or fielding at the time – there is a point that is serious, not to say sinister. It’s not just that tailenders have learned how to bat: it’s that the essential balance between bat and ball has made a significant shift.

It’s easier to bat and score runs than it has been at any time in the history of cricket. The proliferation of huge last-wicket stands indicates that something has gone seriously amiss. Take that England–India game at Trent Bridge. One can be regarded as good fortune. Two looks like misgovernment on a global scale.

Thursday, 16 April 2015

Seattle CEO Dan Price cuts own salary by 90% to pay every worker at least $70,000

Adam Whitnall in The Independent

The tech business founder says CEO pay in the US is 'way out of whack'

A chief executive has announced plans to raise the salary of every single employee at his company to at least $70,000 (£47,000) – and will fund it by cutting his own salary by 90 per cent.

Dan Price, the CEO of Seattle-based tech company Gravity Payments, gathered together his 120-strong workforce on Monday to tell them the news, which for some will mean a doubling of their salary.

Seattle was already at the heart of the US debate on the gulf in pay between CEOs and ordinary workers, after the city made the ground-breaking decision to raise the minimum wage to $15 (£10.16) an hour in June.

But Mr Price, 30, has gone one step further, after telling ABC News he thought CEO pay was “way out of whack”.

In order not to bankrupt the business, those on less than $70,000 now will receive a $5,000-per-year pay increase or an immediate minimum of $50,000, whichever is greater.

A spokesperson for the company said the average salary was currently $48,000, and the measure will see pay increase for about 70 members of staff.

The announcement of the plan was made on Monday (YouTube)

The announcement of the plan was made on Monday (YouTube)

The target is for everyone to be on $70,000 by December 2017, while Mr Price has pledged to reduce his own pay from $1 million a year to the same minimum as everyone else, at least until the company’s profits recover.

Making the announcement, Mr Price said: “There are risks associated with this – but this is one of the things we’re doing to try and offset that risk.

“My pay is based on market rates and what it would take to replace me, and because of this growing inequality as a CEO that amount is really high. I make a crazy amount.

The New York Times, which was invited along for the Wolf of Wall Street-esque announcement, reported that after the cheering died down Mr Price shouted: “Is anyone else freaking out right now?”

Mr Price told ABC News he settled on the figure of $70,000 for all after reading study published by the University of Princeton, which found that increases in income above that number did not have a significant positive impact on a person’s happiness. He said that while he had an “incredibly luxurious life” and super-rich associates, he also had friends who earned $40,000 a year and said their descriptions of struggling to deal with surprise rent increases or credit card debts “ate at me inside”.

Mr Price set up Gravity, a credit card payment processing company, in 2004 when he was just 19. Entrepreneurship runs in the family – his father Ron Price is a consultant and motivational speaker who has written a book on business leadership.

And even if the measure to set such a high minimum wage is a publicity stunt, it has resonated with people in a country where some economists estimate CEOs earn nearly 300 times the salary of their average worker.

Mr Price said he “hadn’t even thought about” how he was going to adjust to earning 90 per cent less, adding: “I may have to scale back a little bit, but nothing I’m not willing to do – I’m single, I just have a dog.

“I’m a big believer in less,” he added. “The more you have, sometimes the more complicated your life gets.”

A chief executive has announced plans to raise the salary of every single employee at his company to at least $70,000 (£47,000) – and will fund it by cutting his own salary by 90 per cent.

Dan Price, the CEO of Seattle-based tech company Gravity Payments, gathered together his 120-strong workforce on Monday to tell them the news, which for some will mean a doubling of their salary.

Seattle was already at the heart of the US debate on the gulf in pay between CEOs and ordinary workers, after the city made the ground-breaking decision to raise the minimum wage to $15 (£10.16) an hour in June.

But Mr Price, 30, has gone one step further, after telling ABC News he thought CEO pay was “way out of whack”.

In order not to bankrupt the business, those on less than $70,000 now will receive a $5,000-per-year pay increase or an immediate minimum of $50,000, whichever is greater.

A spokesperson for the company said the average salary was currently $48,000, and the measure will see pay increase for about 70 members of staff.

The announcement of the plan was made on Monday (YouTube)

The announcement of the plan was made on Monday (YouTube)

Making the announcement, Mr Price said: “There are risks associated with this – but this is one of the things we’re doing to try and offset that risk.

“My pay is based on market rates and what it would take to replace me, and because of this growing inequality as a CEO that amount is really high. I make a crazy amount.

The New York Times, which was invited along for the Wolf of Wall Street-esque announcement, reported that after the cheering died down Mr Price shouted: “Is anyone else freaking out right now?”

Mr Price told ABC News he settled on the figure of $70,000 for all after reading study published by the University of Princeton, which found that increases in income above that number did not have a significant positive impact on a person’s happiness. He said that while he had an “incredibly luxurious life” and super-rich associates, he also had friends who earned $40,000 a year and said their descriptions of struggling to deal with surprise rent increases or credit card debts “ate at me inside”.

Mr Price set up Gravity, a credit card payment processing company, in 2004 when he was just 19. Entrepreneurship runs in the family – his father Ron Price is a consultant and motivational speaker who has written a book on business leadership.

And even if the measure to set such a high minimum wage is a publicity stunt, it has resonated with people in a country where some economists estimate CEOs earn nearly 300 times the salary of their average worker.

Mr Price said he “hadn’t even thought about” how he was going to adjust to earning 90 per cent less, adding: “I may have to scale back a little bit, but nothing I’m not willing to do – I’m single, I just have a dog.

“I’m a big believer in less,” he added. “The more you have, sometimes the more complicated your life gets.”

Friday, 25 April 2014

The high-wire act of modern coaching

Russell Jackson in Cricinfo

Peter Moores now gets a chance to redeem himself after a short-lived first term as a national coach © Getty Images

Enlarge

Sometimes the harder you look at something, the more confusing it seems. Thirty years ago we didn't even have national cricket coaches. Now their appointments, successes, struggles and everything in between are endlessly dissected and considered every bit as newsworthy as the comings and goings of players themselves.

At times we're overly critical of them and at times we probably don't look clearly enough or with sufficient perspective when we shower them with praise. England's recent appointment of Peter Moores is interesting from a number of perspectives and probably encompasses everything that is good and bad about the way we discuss modern cricket coaching.

Here you have a guy who is widely acknowledged as an excellent technical coach, who in his previous attempt at the top job made the mistake of spectacularly failing to manage his relationship with his captain and star player. This kind of personality clash can be inevitable in the workplace but it's poison for coaches, especially when the other guilty party is a once-in-a-generation talent. The buck always stops with the coach, so much so that it almost makes you wistful for the days before they even existed to be blamed by players, fans and media.

On the ABC's Offsiders programme earlier in the year, Gideon Haigh wondered whether Australia's football league, the A League, was "addicted to the smell of death" when it came to the frequent dismissal of managers. Haigh noted, "The attrition rate amongst coaches is very high. It's almost like it's become ritualised, the sense of, 'Who is in the hot seat?' and 'Who is in the tumbrel next?'" The media and fans feed off one and other in that regard and while football codes are still far more susceptible to this mentality than cricket, the curve is trending rather worryingly in the same direction.

It's a bleak situation to ponder, no matter how high the financial rewards offered to modern coaches or the economic factors that hinge on the sustained high performance of their teams. Though it's easy to draw certain parallels between coaches and the cult that surrounds high-powered CEOs, it's with some irony that you have to note that even the most scandal-plagued among the latter rarely receive the same amount of heat in the media as sports coaches. Failures of big business are abstract in some ways, even when they tug at our purse strings. We take sporting failures far more personally.

When speaking of his former national coach Bob Simpson, the first man to fill that position full time and a cornerstone figure in Australia's emergence from the doldrums of the mid-1980s, David Boon theorised that coaches shouldn't stay in their positions for longer than four to five years. Any longer than that and fatigue, complacency or staleness might make lethal encroachments. In modern terms Boon might actually revise that estimate down even lower, because the spiritual toll taken by the relentless demands of coaching at the highest level must be wearying.

Perhaps Andy Flower's brand of dull, robotic, computer-driven managerialism is something closer to a defence mechanism against all of the forces that come bearing down on the modern coach. In that sense, each piece of impersonal protocol and procedure actually places the coach at incrementally farther distances from outsiders, from negativity, but also, it must be acknowledged, positivity and new modes of thinking.

Of course the flip side of the coin that tells us it's the coach's fault when everything is going wrong is that when a team is a raging success, little or no credit is generally attributed to the gaffer. John Buchanan's reign as Australia coach is the best example, obviously. There's no doubt he had a mighty group of players at his disposal but there's also every chance that he, to paraphrase Steve Waugh, got the extra couple of per cent out of them that pushed them on to greatness.

To be positive, I guess there is now the sense that with Kevin Pietersen out of the frame, Moores might now achieve some of the unfinished business from his short-lived first term at the helm of England. What will inevitably nag at him, though, is that at some point he'll be sacked again. Nearly every coach is, eventually. His methods probably won't change dramatically at any point. England will have successful patches and they'll also have unsuccessful patches. In a purely mathematical sense, Moores' fate and the length of his second tenure really hinges on how India and Australia, England's most frequently encountered opponents, develop in the next couple of years.

The same goes for Darren Lehmann, who famously brought the fun back into the Australian dressing room and was one of a team of staff who coaxed the best out of Mitchell Johnson for one golden summer. Sometime in the next few years there'll probably be a slump and he'll be discarded too, just like Mickey Arthur and Tim Nielsen were before him. Hopefully he'll go with a little more dignity, sure, but he knows they'll get him at some point.

All of this really begs the question: if you're a high-level cricket coach with aspirations to maintain a lucrative and lasting career, why would you not do as Victorian assistant coach Simon Helmot recently did and step away from the first-class arena altogether to specialise in the burgeoning T20 format? Jobs are seemingly easier to come by, pay rates range on a scale between handsome and obscene (probably better than all other coaching jobs) and the time away from home is far less demanding.

Say what you like about the IPL and the BBL and the CPL, but loyalty can't be any thinner on the ground there than it is in the international coaching ranks.

Sunday, 1 December 2013

The real cultists are CEOs

The real cultists are not Maoists, they're CEOs

It is not only in religious or political circumstances where people are made to follow a leader unthinkingly

Fred Goodwin is portrayed as a tyrant in a new biography. Photograph: Murdo MacLeod for the Observer

The great leader's followers know he goes "absolutely mental" at the tiniest deviation from the party line. He screams his contempt for the offender in public so that all learn the price of heresy. Go beyond minor breaches of party discipline and raise serious doubts about the leader's "vision" of global domination and that's the end of you. "You're toast," he says, and his henchmen lead you away.

In private, his underlings mutter that the leader is a "sociopath" with "no capacity for compassion". Even though he terrifies them, their hatred of him is far from complete. When he relaxes, the great leader can be charming. His favour brings reward. The further you move up the hierarchy, the more blessings you receive, and the more you believe the leader's propagandists when they hail his "originality" and "rigour". History is vindicating the leader. His power is growing. The glorious day when the world recognises his greatness is coming.

I could be describing Stalin's Soviet Union or the "Church" of Scientology. With last week's allegations that Maoists in south London kept women as slaves, I could be going back into the lost world of Marxist-Leninism. The British Communist party demanded absolute intellectual conformity. Vanessa and Corin Redgrave's Workers Revolutionary party and the Socialist Workers party wanted absolute submission, including sexual submission from women. The UK Independence party meanwhile is looking like a right-wing version of a Marxist sect. Nigel Farage's cult of the personality allows no other politician to compete with the supreme leader and no Ukip official to talk back to him.

As it is, the portrait of a tyrant comes from Iain Martin's biography of Fred Goodwin(one of the best books of the year, in my view). Like a communist general secretary or religious fanatic, he was enraged by the smallest breach with orthodoxy: not wearing the company tie; fitting a carpet in a Royal Bank of Scotland office that was not quite the right colour. The propagandists who praised his rigour and independence worked for Forbes magazine, the Pravda of corporate capitalism. Goodwin took RBS from being a sleepy Scottish bank to a global "player". So history did indeed seem to vindicate him – for a while.

With Britain hobbling in to 2014 like a battered beggar, we should accept that corporations can be as demented and dictatorial as any millenarian movement. People resist the comparison because businesses seem such modest enterprises. The godly persecuted heretics and apostates and the communists punished all dissent because they believed the kingdom of God or workers' paradise could be theirs if believers followed the one true course.

Businesses don't want Utopia. They just want to make money. Dennis Tourish, Britain's best academic authority on how hierarchies enforce obedience, has no problem with the comparison, however. His latest book, The Dark Side of Transformational Leadership,puts the Militant Tendency alongside Enron, the mass "revolutionary suicide" by Jim Jones's followers at Jonestown with the mass liquidation of Britain's wealth by the banks. The ends of an L Ron Hubbard or Fred Goodwin may be incompatible, he says, but the means are same.

In any case, the language of business has become ever more cultish. In the theory of "transformational leadership", which dominates the business schools, the CEO is a miracle worker. In Transformational Leadership, by Bernard Bass and Ronald Riggio, he is described, not by some gullible Forbes hack, but by two supposedly intelligent American academics. The transformational leader "inspires" his follower to "achieve extraordinary outcomes", they say. He "empowers them" to "exceed expected performance" and show ever greater "commitment to the organisation".

I don't see why anyone should find the comparison with fanatics so hard to accept and not only because the idea that CEOs can manufacture new and better subordinates matches Trotsky's belief that the revolution would create a "new man who raises himself to a new plane".

The nearest you are likely to come to experiencing life in a dictatorship is at work. Unless you are fortunate, you will discover that the management is the source of all ideas and all power. Executives will have privileges that bear no more relation to real achievement than the fat and ugly cult leader's expectation of sex. In 2012, the median pay for CEOs in the USA was $14.4m, the average salary for employees $45,230. In Britain, the High Pay Commission found that the average annual bonus for FTSE 300 directors had increased by 187% in 10 years even though the average year-end share price had gone down by 71%.

Above all, whether you are in the public or the private sector, John Lewis or Barclays Bank, you will learn that if you challenge authority you will lose the chance of promotion and if you challenge it in public, you will lose your job. To prosper in the workplace, as in the dictatorship, you must tell leaders what they want to hear.

Since the richest executives on the planet brought the west down, there has been an understandable interest in the psychology of corporate power. One experiment stays in my mind. Researchers divided volunteers into groups of three and gave one the title of "evaluator". Half an hour later, they gave each group a plate of biscuits. The evaluators grabbed more cookies and sprayed crumbs as they ate with their mouths open. After just 30 minutes, the conviction that they were managers produced greed and the belief that normal rules did not apply to them.

I do not doubt that, if required, the courts will deliver justice to the alleged victims of the Brixton Maoists. Justice is harder to find elsewhere. It is not merely that the banking scandals have not led to one prosecution. With the honourable exception of the coalition's push to protect NHS whistleblowers, there has been no interest in making public and private hierarchies less cultish. The left is not saying loudly enough that we need worker directors on all boards as a non-negotiable minimum. The right does not admit that the old way of doing business failed.

In these dismal circumstances, you must look after yourself. If you work in an organisation where you cannot challenge your superiors without fear of the consequences, get out. Stay and you will become a paranoid flatterer. You will suffer all the psychological consequences of living a frightened life in a playground run by strutting bullies. Dennis Tourish's words should be your prompt: the corruption of power may be bad, but the corruption of powerlessness is worse.

Monday, 3 June 2013

Bilderberg 2013 comes to … the Grove hotel, Watford

The Bilderberg group's meeting will receive greater scrutiny than usual as journalists and bloggers converge on Watford

Protesters at Bilderberg 2012. This year's meeting of the global elite is in Watford and is expected to be unusually open. Photograph: Mark Gail/The Washington Post

When you're picking a spot to hold the world's most powerful policy summit, there's really only one place that will do: Watford. I guess the Seychelles must have been booked up.

On Thursday afternoon, a heady mix of politicians, bank bosses, billionaires, chief executives and European royalty will swoop up the elegant drive of the Grove hotel, north of Watford, to begin the annual Bilderberg conference.

It's a remarkable spectacle – one of nature's wonders – and the most exciting thing to happen to Watford since that roundabout on the A412 got traffic lights. The area round the hotel is in lockdown: locals are having to show their passports to get to their homes. It's exciting too for the delegates. The CEO of Royal Dutch Shell will hop from his limo, delighted to be spending three solid days in policy talks with the head of HSBC, the president of Dow Chemical, his favourite European finance ministers and US intelligence chiefs. The conference is the highlight of every plutocrat's year and has been since 1954. The only time Bilderberg skipped a year was 1976, after the group's founding chairman,Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands, was caught taking bribes from Lockheed Martin.

It may seem odd, as our own lobbying scandal unfolds, amid calls for a statutory register of lobbyists, that a bunch of our senior politicians will be holed up for three days in luxurious privacy with the chairmen and CEOs of hedge funds, tech corporations and vast multinational holding companies, with zero press oversight. "It runs contrary to [George] Osborne's public commitment in 2010 to 'the most radical transparency agenda the country has ever seen'," says Michael Meacher MP. Meacher describes the conference as "an anti-democratic cabal of the leaders of western market capitalism meeting in private to maintain their own power and influence outside the reach of public scrutiny".

But, to be fair, is "public scrutiny" really necessary when our politicians are tucked safely away with so many responsible members of JP Morgan's international advisory board? There's always the group chief executive of BP on hand to make sure they do not get unduly lobbied. And if he is not in the room, keeping an eye out, then at least one of the chairmen of Novartis, Zurich Insurance, Fiat or Goldman Sachs International will be around.

This year, there will be a great deal more "public scrutiny" of Bilderberg. Pressure from journalists and activists has won concessions from the venue: for the first time in 59 years there will be an unofficial press office, staffed by volunteers, on the grounds. Several thousand activists and bloggers are expected, along with photographers and journalists from around the world.

Back in 2009 there were barely a dozen witnesses – harassed and arrested by heavy-handed Greek police. This year there is a press zone, police liaison, portable toilets, a snack van, a speakers' corner – all the ingredients for a different Bilderberg. A "festival feel" has been promised. If you are concerned about transparency or lobbying, Watford is the place to be next weekend. Whether the delegates reach out to the press and public remains to be seen. Don't forget, they've got their hands full carrying out the good works of Bilderberg. The conference is, after all, run as a charity.

If you've been wondering who picks up the tab for this gigantic conference and security operation, the answer arrived last week, on a pdf file sent round by Anonymous. It showed that the Bilderberg conference is paid for, in the UK, by an officially registered charity: the Bilderberg Association (charity number 272706).

According to its Charity Commission accounts, the association meets the "considerable costs" of the conference when it is held in the UK, which include hospitality costs and the travel costs of some delegates. Presumably the charity is also covering the massive G4S security contract. Fortunately, the charity receives regular five-figure sums from two kindly supporters of its benevolent aims: Goldman Sachs and BP. The most recent documentary proof of this is from 2008 (pdf), since when the charity has omitted its donors' names (pdf) from its accounts.

The charity's goal is "public education". And how does it go about educating the public? "In furtherance of these objectives the International Steering Committee organises conferences and meetings in the UK and elsewhere and disseminates the results thereof by preparing and publishing reports of such conferences and meetings and by other means." Cleverly, it disseminates the results by resolutely keeping them away from the public and press.

The charity is overseen by its three trustees (pdf): Bilderberg steering committee member and serving minister Kenneth Clarke MP; Lord Kerr of Kinlochard; and Marcus Agius, the former chairman of Barclays who resigned over the Libor scandal.

Labour MP Tom Watson remarks: "If the allegations that a cabinet minister sits on the board of a charity that discreetly funds a secretive conference of elites are true then I hope the prime minister was informed. It was David Cameron who heralded the new age of transparency. I hope he asks Kenneth Clarke to adhere to these principles in future." At the very least, George Osborne and Clarke may consider adhering to the ministerial code when it comes to Bilderberg and declare it in their list of "meetings with proprietors, editors and senior media executives" as they've failed to do in the past. Of course, with the lobbying scandal in full spate it's possible our ministers will steer clear of such a major corporate lobbying event. We'll find out on Thursday.

Sunday, 7 October 2012

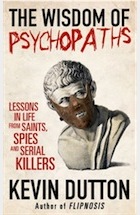

A convincing study shows that business leaders and serial killers share a mindset

The Wisdom of Psychopaths by Kevin Dutton – review

Christian Bale as Patrick Bateman in the 2000 film adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis’s novel American Psycho. Photograph: Moviestore Collection/Rex

Do you think like a psychopath? It has been claimed that one quick way of telling is to read the following story and see what answer to its final question first pops into your head:

- The Wisdom of Psychopaths

- by Kevin Dutton

- Buy it from the Guardian bookshop

- Tell us what you think: Star-rate and review this book

While attending her mother's funeral, a woman meets a man she's never seen before. She quickly believes him to be her soulmate and falls head over heels. But she forgets to ask for his number, and when the wake is over, try as she might, she can't track him down. A few days later she murders her sister. Why?

If the first answer that springs to your mind is some variation of jealousy and revenge – she discovers her sister has been seeing the man behind her back – then you are in the clear. But if your first response to this puzzle is "because she was hoping the man would turn up to her sister's funeral as well", then by some accounts you have the qualities that might qualify you to be a cold-blooded killer – or a captain of industry, a nerveless surgeon, a recruit for the SAS – or which may well make you a commission-rich salesman, a winning barrister, a charismatic clergyman or a red-top journalist. The little parable purports to reveal those qualities – an absence of emotion in decision making, a cold focus on outcomes, an extremely ruthless and egocentric logic – which tend to show up in disproportionate degrees in all those individuals.

There is a problem though. When Kevin Dutton, the author of this compulsive quest into the psychopathic mind, tried the question on some real psychopaths, not one of them came up with the "second funeral" motive. As one commented: "I might be nuts but I'm not stupid."

The admirable quality of this book is Dutton's refusal to accept easy answers in one of the more sensational fields of popular psychology. He comes at the challenge of deconstructing the advantages and dangers of psychopathic behaviour with two distinct motivations. First, the academic rigour of a research fellow at Magdalen College, Oxford. Second, with the more human need to understand the character of his late father, a market trader in the East End, a man with an "uncanny knack of getting exactly what he wanted", who could sell anything to anybody, because to him "there were no such things as clouds, only silver linings". Psychopaths, we learn, are the ultimate optimists; they always think things will work in their favour.

Dutton's curiosity takes him from boardrooms and law courts to neurological labs. He tries in different ways to get inside the heads of those individuals for whom killing has been a way of life – from Bravo Two Zero's Andy McNab to the video game-obsessed inmates of Broadmoor's secure wards. In his effort to get to their truths he has a tendency to write with the one-tone-fits-all breeziness of the excited enthusiast; at certain points his insistent chattiness jars. Though he demonstrates few of the characteristics of psychopaths himself, none of the limited range of cold fury of Viking "berserkers" or the wilful icy detachment of brain surgeons, he is in thrall to their possibilities. Perhaps, he argues, we all are.

Dutton's book at any rate supports the idea that to thrive a society needs its share of psychopaths – about 10%. It not only shows the value of the emotionally detached mind in bomb disposal but also the uses of the psychopath's ability to intuit anxiety as demonstrated by, for example, customs officials. Along the way his analysis tends to reinforce the idea that the chemistry of megalomania which characterises the psychopathic criminal mind is a close cousin to the set of traits often best rewarded by capitalism. Dutton draws on a 2005 study that compared the profiles of business leaders with those of hospitalised criminals to reveal that a number of psychopathic attributes were arguably more common in the boardroom than the padded cell: notably superficial charm, egocentricity, independence and restricted focus. The key difference was that the MBAs and CEOs were encouraged to exhibit these qualities in social rather than antisocial contexts.

As Dutton details this relationship, part of you is left wondering if the judge who recently praised a housebreaker for his courage and resourcefulness, and expressed the hope that in the future he might use his energies in more constructive directions, might have had Dutton's book by his bedside. Certainly you are left wondering if corporations that really want to find driven leaders might be as well to conduct their recruitment round in the juvenile courts as the universities. In this sense it is hard to know which is more chilling: the scene in which Dutton weighs a serial killer's brain in his hands and reveals it to be in no way tangibly different from yours or mine, or the research that shows the ability of American college students to empathise with others has, in the past 30 years, reduced by 40%…

Wednesday, 16 May 2012

India Inc. and Its Moral Discontents

By Ravinder Kaur in EPW

While the Arab revolts were challenging

the western hegemony

to pave way for grass-roots

democracy last year, India was witnessing

a different kind of mass mobilisation

dramatically named by a few in the

media as the “second struggle” for Independence.

Delhi – like Cairo, Tunis,

Damascus and Manama – had become

the centre of protracted though nonviolent

popular protests with demands

for accountability from the corrupt ruling

elite. The media even took to describing

the protests affectionately as “our Arab

spring” and likened the site of protests in

Delhi as “our Tahrir Square” – imbuing

the event with revolutionary fervour

and turning it into a kind of catharsis

necessary to purify a corrupted postcolonial

nation. That these protests were

largely composed of a restless youth

population – though reliably steered by a

non-partisan “Gandhian” patriarch –

only served to make the comparisons to

the Arab revolts seem natural. Yet the

differences could not be starker. Unlike

the uprisings in west Asia that sought

to address the societal crises – rising

inequality, infl ation, massive unemployment,

lack of political freedoms and

disenchantment with the ruling elite –

as political subjects seeking political

change, the popular mobilisation in

India has primarily been the work of

“apolitical” activism more in tune with

the Tea Party movement of the United

States given its neo-liberal fantasies of

“small government”.

This essay sets out to unpack the economy

of the moral outrage we have witnessed

the past several months and which

continues to occupy a central position on

the nation’s agenda. The prime question

that needs to be asked then is, how and

when did corruption become the most

pressing crisis facing the Indian nation?

And in whose interest has this project

of moral cleansing of the nation been

affected? This line of enquiry opens up

some provisional answers that help explain

a movement that has built upon a

successful coalition of as diverse interests

as the techno-elite, professional middle

class, the urban poor, the religious and the

secular-minded individuals, big corporations,

global non-governmental organisations

(NGOs) and localised neighbourhood

associations. Three crucial interrelated

developments within the Indian

socio-political landscape can already

be noted in this regard. First, the neoliberal

conception of the nation-form as

commodity-form that India has steadily

transformed into since the 1990s economic

liberalisation. The success of the

nation is now no longer measured by its

ability to secure territory and the welfare

of its people alone, it is primarily

measured by its ability to attract capital

investments and maximise revenues.

The Indian nation has acquire d a new

nomenclature – India Inc. – that is vastly

popular within the corporate and policymaking

circles. The addition of the suffi

x “Inc.” highlights the corporate character

of the nation that has become its

prime identity in the past two decades.

It is following this neo-liberal logic of

nation as corporation that Prime Minister

Manmohan Singh is often addressed as

the chief executive offi cer (CEO) of India.

This popularly bestowed title gains particular

currency in his case as he is seen as

the main architect of the Inter national

Monetary Fund (IMF)-World Bank-led

economic reforms in early 1990s.

Second, corporations as well as global

bodies like the World Bank have increasingly

become invested in initiating

reform s at the social level in India. The

widely shared belief is that India is unable

to reach its full potential as a global economic

powerhouse precisely because of

socio-cultural constraints. The culture

of corruption – bribes, nepotism, and lack

of transparency within the governmen t

– is seen as one of the biggest impediments

to complete market reforms. The

anti-corruption mobilisation, thus, has

substantial support from the corporate

sector including several corporationcontrolled

newspapers and television

channels. Third, not only is a corrupt

government found detrimental to India’s

rise as a great power, the government

itself is seen as an impediment in the

path to that goal. A particular feature of

the anti-corruption protests is the outrage

against the government as the primary

source and cesspool of corruption. This

popular view is in line with the neoliberal

belief in “less government” and

more market as the path to economic

growth and prosperity. In other words,

to speak of politics – and anti-politics –

of anti-corruption mobilisation in India

today only in terms of “the people”,

“government” and “civil society” is to

miss out on new realities that constitute

the reformed Indian nation. Not only do

corporations play a dominant though

unpublicised role in the currents of Indian

politics, the Indian nation itself has been

reinvented as a corporate body whose

legitimacy is derived from its ability to

maximise revenues and profi ts. This nexus

between corporations, global fi nan cial

institutions and the anti-political populist

rage is key to understanding the new

agenda of nation’s moral cleansing.

What follows is an attempt to outline

the corporate logic of the moral panic

in India.

2 Nation as Commodity

In the past two decades, the free-market

logic of the nation state has increasingly

become visible not only in the attempts

to patent national commodities, but the

nation itself. The nations, especially those

most newly reformed such as India, are

branded, graded and placed within the

global hierarchy of nations according to

their success in attracting foreign direct

investments (FDIs) as well as revenues

from tourism. This commodifi cation of the

nation – as a profi t-making enterprise –

lies at the heart of this great neo-liberal

transformation. The unique assets of

the nation – its culture, history, natural

resources, human labour, locality, and

the inalienable essence that makes it

authentic – are commodifi ed in order to

maximise its capital and expand its power

in the global scheme of things. Nationality

Inc. blurs the lines between the state

and market to an extent that the state no

longer merely exists as the “monitor” of

the market, instead the market becomes

the underlying principle of the state.2 As

Jacques Ranciere (1999), recalling Marx’s

once-controversial assertion that governments

are simple business agents for

international capital, suggests, it is now

an “obvious fact…the absolute identifi -

cation of politics with the management

of capital is no longer the shameful secret

hidden behind the ‘forms’ of democracy; it

is the openly declared truth by which

our governments acquire legitimacy.

The role of the state as an active economic

agent – a corporation in search of

ever greater profi ts and revenues – has

always existed, the neo-liberal thinking

has only brought out in plain sight the

well hidden secret: the collusion between

the domain of politics and the

domain of the economy. In short, the

neo-liberal turn has surfaced the disarticulations

of the hyphenated dialectic

condition that binds the nation with the

state, and instead fully revealed the

corporate logic of the nation. India Inc.,

the new nomenclature for the nation is,

thus, suggestive of the new species of relations

between the market and the nation

where the Indian state appears as a

facilitator for the circulation and maximisation

of capital.

A significant part of the economic

reforms which opened India to flows of

FDI, private participation in the domain

of government, and withdrawal of the

state from the social sector has been the

attempt to brand the nation in the global

market. As early as 1996, the Indian

state had created a subsidiary agency of

the Ministry of Commerce – India Brand

Equity Foundation (IBEF) – with the primary

task of marketing “Made in India”

products around the world. This lagging

project was revived in late 2002 by the

National Democratic Alliance reform

minded government though with a redefi

ned task – to not only showcase Indian

brands abroad but transform India itself

into a corporate brand. The offi cial brief

was now to “celebrate India” as the “destination

of ideas and opportunities” in

order to bring in FDI as well as invigorate

tourism.

And by 2004, Brand India was

set in motion to “build positive economic

perceptions of India globally”.6 The new

initiative not only formalised the corporate

approach to governing the nation, it

also confi rmed the alias by which the

nation is known in the corporate world

– India Inc. – an entity consequently

gover ned by a CEO rather than a political

representative.

One of the key tasks for India Inc.

unsurprisingly, then, has been that of

image making primarily for a global

audience – corporate investors, leaders of

global fi nancial institutions and wealthy

tourists. Two Delhi-based advertising

agencies specialising in place branding

were recruited to create a distinctive

logo, a slogan and a “business kit” to be

presented through glossy campaigns in

print and electronic media.8 While one

of these agencies is responsible for creating

a more popular and vastly visible

global campaign called “Incredible India”

mainly to attract foreign tourists, the

second agency works hand in hand

though with little visibility within India

to enhance “Brand India” in the global

fi nancial markets. Brand India unveils

its annual advertising blitzkrieg spectacularly

at the World Economic Forum,

Davos amidst an assembly of corporate

heads, leaders of industrialised nations

and functionaries of global fi nancial

institutions. The idea is not only to

familiarise the world fi nancial leaders

about the current state of Indian economy

but also to report back on the progress

made by the Indian state vis-à-vis

economic reforms.

The corporate sector in India together

with the global financial institutions

perceives the 1991 economic reforms as

incomplete and partial, and each successive

government is therefore routinely

asked to undertake further “unshackling”

of the economy and take the reform to

its logical conclusion: a fully liberalised

market economy without regulatory

oversight and constraints affected by the

social and environmental costs. Davos is

one such prominent location where reformed

nations are reviewed in a global

setting – the “good governments” are

celebrated, whereas those lagging behind

are warned and encouraged to follow

suit. India Inc. has been both a subject of

celebration and warnings about its inability

to reach its potential. The little understood

complexities of Indian sociopolitical

order – caste stratifi cations, religious

divisions, communal violence,

and more importantly now, the “culture”

of corruption – are often posed as impediments

in India’s path towards economic

growth. The question confronting the

corporate state – an effective imagemachine

– is: how to create a desirable

image of the nation while erasing or

minimising the effect of all that “holds it

back”? Or more concretely, how to

project India as the most “attractive” investment

destination in order to lure

away potential investors from other

competing nations in the world.9 The

answer, in branding parlance, is to minimise

the “negatives” – associations with

poverty, archaic social practices, political

turbulence, and corrupt practices –

to halt the adverse news flow about the

nation in global media. This constant

quest for an attractive brand image and

the fear of the contaminating effect of

powerful negatives such as corruption,

then, is a partial explanation for the

moral discontent that is currently raging

in India.

Economy of Moral Panic

Anna Hazare’s protest agitation began in

the heart of Delhi – Jantar Mantar, a

part tourist attraction, and part zone of

protest – chiefl y to demand the passage

of the Jan Lokpal Bill (People’s Ombudsman

Bill) as a strong anti-corruption

instrument. The crowds that thronged

the protest site – adorned with symbols

borrowed from the repertoire of Hindu

nationalists and to the chants of Vande

Mataram – in support of the Bill had

pitted themselves not only against the

government’s version (the Lokpal Bill),

but the entire political class as such. And

if there was an enemy in this struggle,

then it was the fi gure of the politician –

usually depicted as a slick character

with easily compromised morals and infi

nite greed for ill-gotten wealth stashed

away in Swiss vaults – that had permeated

the popular imagination egged on by

the rhetoric of protest. The less visible

spokes of the government machinery –

the bureaucrats – were found equally

guilty of entrenching a system that did

not move without adequate grease in the

form of bribery and nepotism. In other

words, it was the domain of government

that had been identifi ed as the root

cause of the rot and therefore in need of

instant repair. This form of identifi cation

also disclosed the collective body of

“the people” in a state of isolation from

the government. Not only was the government

viewed as corrupt, the very

idea of state and government was now

shaped through the discourse of corruption.

Accordingly, the provisions of the

people’s bill focused mainly on the

conduct and practices of public functionaries

which through a series of legislations

– disciplinary measures and

punishment – could be rectifi ed and

controlled. The wider socio- economic

landscape – social injustice and inequities

– around which the notion and practice

named as corruption thrives was hardly

the focus of the protests.

The most telling aspect of both the

competing legislative bills, however, was

the stark absence of any provisions to

scrutinise corporate corruption. This absence

is particularly signifi cant as most

of the scams in India are related to

murky corporate practices ranging from

provision of supposedly mandatory kickbacks,

bribes to impart fl exibility to

existing rules, purchasing infl uence

within the government to ensure friendly

policies, evading taxes, and committing

fi nan cial fraud. Yet, the corporations

appear in the debate, if at all, as victims

of corruption in the domain of government

that hinders the nation’s economic

growth. This is not entirely unsurprising

in a neo-liberal state where the greatest

fear is the fear of failure to attrac t investments

and a slowdown in the pace

of economic growth. But what is surprising

is the intensity with which this

logic has fi ltered to the core of elite politics

in India to an extent that corporate

excesses are more or less effaced from

the public debate.

Corruption has long been seen as an

impediment towards free market and

economic growth. And in the anticorruption

movement, the corporations

have been able to fi nd articulations of

their own interests that seemingly are in

tune with the public outrage harnessed

successfully by the civil society. Even

before the popular protests had taken

off, the Federation of Indian Chambers

of Commerce and Industry (FICCI) had

issued a statement calling for probity in

governance in order “to preserve India’s

robust image and keep the growth story

intact”.10 This was followed by an open

letter by 14 prominent individuals – corporate

leaders, reform-minded economists

and bureaucrats assembled together

under the sign of the “citizen” –

who identifi ed corruption as the “biggest

issue corroding the fabric of our nation”.

The recommendation of the group was

to address the “governance defi cit” that

had permeated every level of state institutions,

and to restore the self-confi dence

of Indians in themselves and in the Indian

state.11 When the protest began gathering

steam, the biggest support to fi ght

corruption came from the corporate

sector. The corporate leaders expressed

their support publicly proclaiming that

“we completely support Hazare in his

fi ght against corruption which has been

denting India”.12 The corporate voices

had not only begun addressing Anna

Hazare as a moral crusader, but in one

instance also as “prime minister” – the

only one morally clean and worthy of

leading the nation – to show their disaffection

with the elected representatives.

13 In other words, the malaise

ailing the nation had been primarily

isola ted within the domain of government,

and only by exposing and emptying

it out in the public could the nation

be put on the path of purifi cation.

The power and infl uence of the corporations

in the anti-corruption movement

can be gauged from the fact that hardly

any critical voices have been heard

demanding corporate accountability.

Yet, bribe-giving or purchase of infl uence

in the government is often seen by

both Indian and foreign businesses as

an acceptable practice. In a survey of

European fi rms conducted earlier this

year, about two-thirds of corporate

employees named bribe-giving as a widespread

strategy to win contracts and

retain businesses.14 Similarly, a Bribe

Payers Index (BPI) found corporate corruption

to be rampant in the “emerging

markets” and particularly entrenched in

sectors like infrastructure development,

construction, mining, oil and gas explorations

and property development.15 The

State’s fear of losing corporate investments

and the attendant possibility of

job creation and revenue generation

means that there is little challenge to

corporate corruption. Instead, the neoliberal

states go out of their way to facilitate

businesses and overlook any exce sses.

This anxiety of alienating corporations

was visible in the controversy over the

2G court case. The union minister of law,

Salman Khurshid, chided the Supreme

Court for not granting bail to businessmen

accused in the 2G spectrum scam.

He was reported as saying, “If you lock

up top businessmen, will investment

come?” to voice his concerns over threat

to the pace of economic growth and

investment in the nation.16 In this case,

17 individuals were arrested and prosecuted

including the former Telecom

minister A Raja and several senior executives

from some of the largest telecom

companies in India. But somehow the

corporate executives escaped the harsh

probing of their conduct in the public

domain whereas the politician involved

was transformed into a symbol of all the

systemic failures and corruption plaguing

the nation. In short, it is the fi gure of

the politician that is frequently evoked

to rouse public passions in the anticorruption

movement while the businesses

are either seen as hapless victims

of the “system” or kept out of public

spotlight when the irregularities are too

momentous to be ignored.

4 Global Panacea of Reforms

The excessive focus on government

together with the near effacement of

corporations from the anti-corruption

discourse is neither an accident nor an

oversight. Rather it is a refl ection of the

global processes that began intensifying

in the past two decades surfacing civil

society as a key player in the domain of

governance. Central to this shift was not

only the lack of belief in the State’s capability

to check corruption, but the fact

that the institution of state per se was

viewed as intrinsically corrupt. The very

defi nition of corruption, at the height of

modernisation theory, came to be particularly

tied to the misuse of public offi ce

for private gains.17 Any checks against

corruption would, then, logically mean

checks against the government itself

which was now largely viewed through

the lens of corruption. This spectre of

corruption became a familiar theme that

was often played out in the context of

the Third World thought to be in particular

need of western style rational

modernisation and development to overcome

the culture of corruption. The anticorruption

campaigns, thus, were initiated

in harmony with the push for structural

reforms in developing countries – more

free market equalled less corruption.

In the early 1980s, coinciding with the

thrust towards structural reforms, the

global institutions such as the World

Bank and IMF began turning their focus

on the “cancer of corruption”18 on the

one hand, and greater collaboration

with civil society organisations (CSOs)

on the other.19 This was the moment

when one could witness the successful

co-option of the robust tradition of protest,

dissent and speaking truth to power

– by ordinary people against hegemons

– by powerful global institutions to

serve its own agendas. While corruption

was necessarily seen as endemic in the

nation states of the South,20 the CSOs

were encouraged and “empowered” as a

way to minimise the infl uence of the

corrupt and ineffi cient states.21 This focus

on indivi dual cooperation at societal

level outside the domain of government

was argued forcefully as “social capital”

– a cost-effective mode that successfully

limits the government and promotes

modern democracy – by neo-liberal

advocates such as Francis Fukuyama.22

The long-standing tradition of public

activism for public good was, thus, successfully

harnessed to the realisation of

neo-liberal ideals of small government.

Accor ding to World Bank’s estimates,

the CSO sector worldwide is currently

worth $1.3 trillion annually employing

about 40 million people, and channels

fi nancial assistance of about $20 billion

to the developing nations per year.23 The

CSOs are involved in up to 81% of the

Bank-funded projects with a presence in

over 100 nations around the world.

In a recent report published at the

height of the anti-corruption movement,

these seemingly disparate themes – of

corruption, civil society, popular protests

and liberalised markets – were joined

together to weave the narrative of moral

breakdown in the society and its cost to

the Indian economy. The report begins

by evoking the World Economic Forum’s

Global Competitiveness Index24 that

lists a number of freedoms necessary for

a nation’s economic competitiveness

(business freedom, trade freedom, fiscal

freedom) of which India particularly

suffers from the lack of the “freedom from

corruption” that could derail its projected

economic growth and may result in a

volatile and economic environment.25

Nearly one-third of the respondents

believed corruption to be particularly

detrimental to India’s growth poten tial,

while 93% agreed that “corruption

negatively impacts the capital market”.

The lowered levels of ethical values in

the society were no longer merely a

matter of individual immorality and

concern, they had a severe economic

cost for the nation especially its brand

image in the world. The issue of personal

and corporate corruption – evasion of

taxes, for instance – was explained away

in terms of tight regulation and high tax

rates that help produce corruption in

the society.

The successful harnessing of populist

indignation to a cause much favoured by

corporations and global financial institutions

– of free markets – is best illustrated

in the solutions offered to regulate

corruption. Here the provisions of the

people’s bill promoted by the civil societ y

are mirrored in those favoured by the

corporations.26 These include stringent

punishment, high penalties and zero

tolerance to corruption through the establishment

of fast track courts, and special

enforcement powers to the Lokayukta,

or Ombudsman’s offi ce. Remarkably, in

step with the neo-liberal thinking, the

state makes reappearance here in its

new recommended role as that of a strict

regulator of anti-corruption laws and

facilitator of suitable conditions for businesses

to operate in. In this vein, Chinese

state’s solutions to control corruption are

often quoted admirably by the business

community and these include high fi nes

and even imposition of death penalty.27

The Indian model, on the other hand,

with its democratic messiness is seen as

less than ideal for businesses to fl ourish

in. It is ironic that the neo-liberal language

of freedoms that is usually adopted

to advocate for free markets is rendered

speechless when it comes to corruption.

Not only does it look towards an

authoritarian state such as China for

inspiration, it also resurrects the much

despised state to provide legal framework

to control corruption.

Consensual Politics

While the anti-corruption protests have

been widely analysed, and at times even

celebrated, in terms of agonist politics in

a non-violent, democratic space, a closer

look at the movement, its motives, organisation

and opposition shows far

more consensual politics at play between

the government and the protestors than

is commonly believed.28 To begin with,

there is hardly any disagreement with

the central objective of the movement

which is to control and cleanse the public

life of corruption in India. The harmful

effects of corruption on the nation’s

brand image as well as its competitiveness

among businesses and investors

are well understood by the state as well

as the protestors. Though the plight of

the “common man” is the rallying cry

that mobilises diverse groups and interests

– the perception of oneself as victim

of corruption is universally shared

– under the sign of “the people”, it is the

goal of greater reforms and economic

freedoms that guides this politics of

consensus. The differences between the

government and the protestors are of a

more technical as well as tactical nature

concerning the specifi c details of the

regulatory bill and the time duration

within which the bill is expected to

be passed.

That the state is as eager to seize the

populist issue of corruption – and to be

seen as progressive on the economic

growth front – is clear from the ways in

which it responded to the anti-corruption

protests. The protestors were mostly

indulged, and if at all mildly rebuked, in

a manner that appears in stark contrast

to the usual conduct of the police authorities.

The police neither seriously

attempted to disperse the crowds nor

did it pose effective curtailments to contain

the protests. And when Anna Hazare

began his fast-unto-death the second

time around, no one tried to intervene in

order to put an end to his chosen form of

protest. This could not be more different

than the way in which the civil

rights activist from Manipur, Irom

Sharmila, has been dealt with by the

state. She has been on indefi nite hunger

strike for the past decade to protest

against the Armed Forces (Special Powers)

Act, 1958 (AFSPA) which gives exceptional

powers to the army to discipline

what are called the “disturbed areas”

of northeast India. The most striking

reminder of the sovereign state’s power

to intervene and disrupt are the leaked

images of Irom Sharmila being force-fed

through tubes in order to keep her alive.

Unlike Anna Hazare’s widely celebrated

movement, her cause is not universally

shared in the urban middle class electorate

as well as the ruling elite. If anything,

it is seen as a threat to India’s