by Girish Menon

The pre-season games played by (CamKerala 3) CK3 on 25 April and 17 April resulted in three wins: one a close 2 run defeat of CK2 and two bigger wins over CK1 and Reach CC’s Sunday 11.

The games on 17 April saw CK3 usurp the title of CamKerala champions after beating CK2 in a qualifier before defeating CK1 in the finals. The prevalent hierarchy in CamKerala was shattered and left the defeated teams thirsting for an urgent rematch to restore what they believe is a 'natural' pecking order.

Yesterday saw a rather one sided game in the fields of Reach a village 12 miles east of Cambridge. This hitherto 'open toilet' ground now has its own eco-toilet (not usable though!) hence CK3 players continued to discharge water in the open.

CK3 won the toss and scored over 230 runs in a 35 over game. CK3s cricketers with tennis ball training led the way with a flurry of 4s and 6s. Captain Saheer retired after preventing what could have been a collapse and the tail wagged so much that Martin could not get a bat. This led to the revival of the contentious issue whether batsmen should retire after facing a certain number of deliveries.

When CK3 bowled, Saheer set an umbrella field previously seen only when Lillee and Thomson used to bowl way back in the 1970s. There were nearly 3 slips and a gully to Jithin’s good pace and bounce and this writer dropped two chances behind the wicket. When Martin bowled his field was short point, short cover, silly mid off… and Sharad caught two batters at short point off Martin’s ‘moonballs’. Then there was a procession of batters and the match ended 15 overs before time.

The pitch had high bounce and deviation on most deliveries whilst some deliveries crept along the ground giving this writer tremendous difficulty behind the sticks. The match ended with one CK3 player locked out of his car and three team mates with fuel running on reserve wondering whether they would make it to the nearest petrol station without trouble.

There was a lot of laughter and merriment while CK3 bowled which I hope will continue for the rest of the season.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label bat. Show all posts

Showing posts with label bat. Show all posts

Monday, 26 April 2021

Thursday, 12 November 2015

Batting:The downside of up

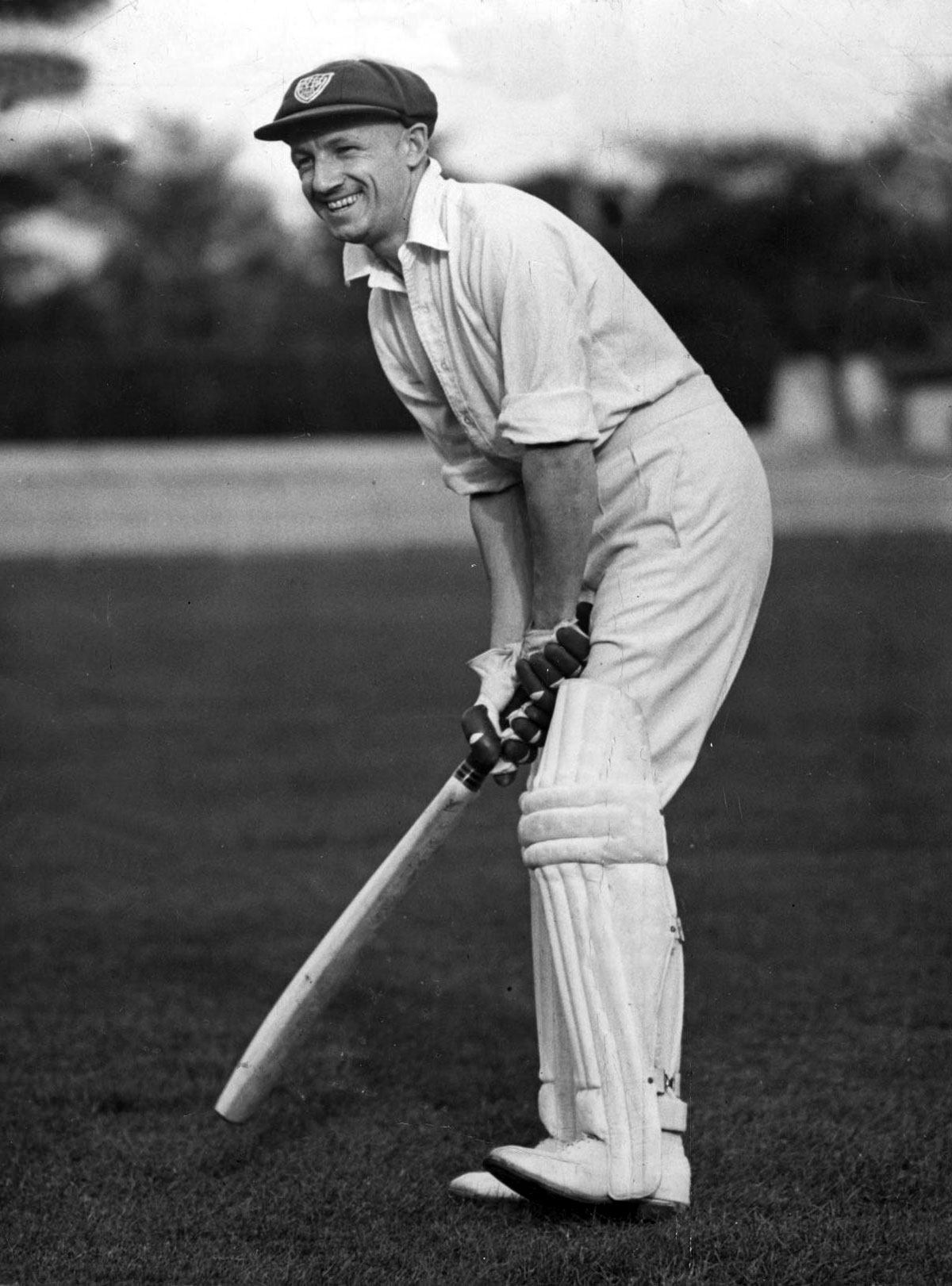

Grounded for life: Justin Langer at the Gabba© Getty Images

What began as a technical tweak for one Aussie batsman is now a nationwide fad. And not everyone is impressed

SB TANG in Cricinfo | NOVEMBER 2015

For the first 128 years of Australia's Test history, there was one constant in a boundless sea of technical heterodoxy - great Australian batsmen gently and rhythmically tapped their bats on the ground as the bowler ran in, and kept their bats grounded until around the time the bowler jumped into his delivery stride.

Every permanent member of the top seven (Matthew Hayden, Michael Slater/Justin Langer, Ricky Ponting, Mark Waugh, Steve Waugh, Damien Martyn and Adam Gilchrist) of Australia's victorious 2001 Ashes team - the last to win an Ashes series on English soil - adhered to this method.

Mike Hussey was not a member of that top seven. In the English summer of 2001, Hussey was a 26-year-old Western Australian opening batsman who had never played for Australia at the senior level. In the preceding Australian summer, he had averaged 30.25 in first-class cricket, passing 50 only twice in 21 innings. In the seemingly ever-growing queue of applicants for a spot in the Test line-up, he was, at a conservative estimate, behind Slater, Simon Katich, Darren Lehmann, Brad Hodge, Martin Love, Matthew Elliott, Jimmy Maher, Greg Blewett and Jamie Cox.

As a kid acting out his dream of playing for Australia in backyard games with his younger brother David in the beachside Perth suburb of Mullaloo in the '80s, Hussey tapped his bat and kept it down because, as he revealed to the Cricket Monthly, all the guys he watched batting for Australia, "likeGreg Chappell" and his "hero", Allan Border, did so. The thought of holding his bat up like a baseballer never occurred to him as a kid; none of the Australian Test batsmen he watched and admired did that.

When Hussey scored his solitary first-class hundred of an otherwise dismal summer in March 2001, he was still tapping his bat and keeping it down. But not long thereafter, he realised he had a problem that he would have to rectify if he was to realise his dream of playing for Australia - his bat-tap was causing his head to "fall over too much towards the off side and so… was having trouble hitting the balls off his pads and getting LB". Hussey is five foot ten inches tall and has "quite long legs". He "tried batting with a long blade bat, just to try and keep myself a little more upright and keep my weight more upright, but every time I leant over to tap the bat it took my head over [towards the off side] and I had bad balance".

The pioneer: Mike Hussey's success with holding the bat up in the stance kicked off a revolution in Australian cricket © AFP

Some time after that middling season - he can't remember exactly when - Hussey did something momentous, something that - according to photographic and video evidence compiled by Dean Plunkett, the WACA's Performance Analysis Coordinator - no great Australian Test or Sheffield Shield batsman before him had done: he got rid of his bat-tap and started holding his bat up above knee level as the bowler ran in to bowl. Since his bat-tap was causing his head to fall over, he reasoned that removing it and "standing upright" would enable him to get his head into the best balanced position and "access the straight balls a bit better".

Once he went bat-up, Hussey was unstoppable. He made his one-day international debut in February 2004 and his Test debut in November 2005. After his first 20 Tests, the only batsman he could statistically be compared with was Donald Bradman - he was averaging 84.80.

Hussey retired from Test cricket in January 2013 - with 6235 runs and 19 hundreds, at an average of 51.52 - as the first great Australian Test batsman to use a bat-up technique.

He won't be the last.

Steven Smith uses a bat-up technique. When Australia won a fifth World Cup earlier this year, five batsmen - Smith, Aaron Finch, Shane Watson, Glenn Maxwell and James Faulkner - in Australia's top seven used bat-up. (A sixth member of that top seven, Michael Clarke, could be argued to have had a bat-up technique by that very late stage of his illustrious career, having been bat-down for most of it.)

The significant, and growing, proportion of Australian batsmen who have started holding their bats up like baseballers over the past decade has been, to borrow a phrase from WG Grace, one of those "silent revolutions transforming cricket". Chappell certainly believes so. He said that it's "a revolution that is changing batting like it's never changed before in the history of the game".

Ed Cowan grew up in Sydney, with a poster of Ricky Ponting on his bedroom wall, as a naturally attacking, free-flowing batsman who destroyed bowling attacks and once, according to the renowned junior coach Trent Woodhill, scored 199 off 34 overs in an Under-21 game.

Greg Chappell, one in a long line of bat-down Australian batsmen, believes the traditional method is more efficient since it helps synchronise hand and foot movement © Getty Images

Cowan said he "had always been a very strong back-foot player" and had pulled and hooked the quicks fluently at first-grade level. But, he explained, "when you hit first-class cricket you go from facing guys bowling 125 k's an hour and wickets that don't tend to bounce above your belly button in club cricket to [faster, bouncier] first-class wickets", and bowlers averaging 135kph and regularly exceeding 140. In Cowan's first three Shield matches in early 2005, he faced: Shaun Tait (in his fearsome prime), Ryan Harris, Andy Bichel, Ashley Noffke, Steve Magoffin and Brad Williams. Those blokes didn't bowl at 125kph.

The 22-year-old Cowan quickly realised: "I can't [hook and pull fluently] at this level and I need to find a way because it is limiting what I am doing." He looked at what the best batsmen in Australia and the world were doing. What he saw, in the Australian winter of 2005, was: "the best player in the [New South Wales] squad" and "probably the best player of the short ball in Shield cricket at the time", Katich, with his bat up; Jacques Kallis, one of the best batsmen in the world, with his bat up; Kevin Pietersen, a swashbuckling 25-year-old whose maiden Test hundred had just consigned Australia to their first Ashes series defeat in nearly 19 years, with his bat up; and Hussey, who had an ODI average of 123.50 and a strike rate of 94.45 after the first 21 months of his international career, with his bat up.

Thus, Cowan decided to experiment with his bat up to try to give himself "a chance to play" the hook and pull shots against Shield quicks. Like Hussey before him, Cowan made the decision to go bat-up himself and takes full responsibility for it. He had a conversation with Trevor Bayliss, NSW's coach at the time, about his decision. Bayliss, like most of the best coaches in the land, respected the player's decision. He made no attempt to change it, but he did explain the inherently risky nature of any technical change.

Australian cricketers are always looking for a competitive edge. Their "Darwinian first-class competition", in the words of historian Gideon Haigh, demands it. In light of that and what Haigh calls the "Australian tradition of autodidactism", it was inevitable that once some batsmen, especially a prominent Australian, started dominating at Test level with a bat-up technique, young Australians would give it a go. As Cowan explained: "You can't stop searching for improvement and I think that's player-driven because… players want to perform." For example, "I don't think Steve Smith liked getting out caught in the slips consistently [when he first came into the Test XI in 2010]", therefore, he worked his tail off and rectified that problem by, among other things, adopting a bat-up set-up in around May 2013.

Ian "Mad Dog" Callen played one Test for Australia against India at the Adelaide Oval in 1978, taking 6 for 191 - including the prize wicket of Sunil Gavaskar - to help Bob Simpson's Packer-depleted Australian side win the Test and clinch the five-match series 3-2.

Up or down? Should kids be allowed to develop their own rhythms? © Getty Images

Callen now lives on a property named Kookaburra, near the small Victorian country town of Tarrawarra with his wife, Susan. He greets me with a warm grin inside the two-storey wooden barn, nestled at the bottom of a grassy hill, where he spends his days hand-making cricket bats from his own Australian-grown English willow and training Australian bat-makers in the ancient craft. He takes a seat at the dining table, directly underneath his framed Australian team blazer from the 1977-78 tour of the West Indies, and highlights two technological reasons why the bat-up method has risen in popularity in Australia over the course of the last decade: helmets and bats.

Firstly, the more upright bat-up batsman presents a bigger target for the fast bowler with a good bouncer than the classical, bat-down batsman who is tapping his bat (and therefore at least slightly crouched, on his toes, at the ready, like a boxer). Thus, in the pre- and early-helmet era, the greater likelihood of being struck by a bouncer dissuaded batsmen from going bat-up. However, by the mid-2000s, advancements in helmet technology had greatly reduced the risk of serious injury.

Secondly, Callen found, through systematic testing, that the quality of the sweet spot on a good English willow bat has not changed much, if at all, over the last century - if you drop a ball onto the sweet spot of a 1930s bat, it will bounce as high as one dropped onto the sweet spot of a current-day bat. But the size of the sweet spot has increased exponentially. Therefore, today's batsmen have a much greater margin for error than batsmen in the 1930s or even the 1970s.

Proponents of the bat-down method, such as Chappell, who is now Cricket Australia's National Talent Manager, believe that it enables a batsman to more easily synchronise his hand and foot movement, thereby making it easier for him to get into "a more optimal position" to play the shot that he has imagined, "at the correct time", which in turn enables him to consistently hit "the ball in the middle of the sweet spot". There is obviously less need for him to do that if the sweet spot on his bat is much larger. According to Chappell, bat-up is a "less efficient" method of batting and "it's probably the improvement in the bats that has allowed these [less efficient] methods to prosper, because the mishit goes better than it's ever gone before, so batsmen are probably not getting the feedback… that these methods are less efficient than methods that have been used before".

Firstly, the more upright bat-up batsman presents a bigger target for the fast bowler with a good bouncer than the classical, bat-down batsman who is tapping his bat (and therefore at least slightly crouched, on his toes, at the ready, like a boxer). Thus, in the pre- and early-helmet era, the greater likelihood of being struck by a bouncer dissuaded batsmen from going bat-up. However, by the mid-2000s, advancements in helmet technology had greatly reduced the risk of serious injury.

Secondly, Callen found, through systematic testing, that the quality of the sweet spot on a good English willow bat has not changed much, if at all, over the last century - if you drop a ball onto the sweet spot of a 1930s bat, it will bounce as high as one dropped onto the sweet spot of a current-day bat. But the size of the sweet spot has increased exponentially. Therefore, today's batsmen have a much greater margin for error than batsmen in the 1930s or even the 1970s.

Proponents of the bat-down method, such as Chappell, who is now Cricket Australia's National Talent Manager, believe that it enables a batsman to more easily synchronise his hand and foot movement, thereby making it easier for him to get into "a more optimal position" to play the shot that he has imagined, "at the correct time", which in turn enables him to consistently hit "the ball in the middle of the sweet spot". There is obviously less need for him to do that if the sweet spot on his bat is much larger. According to Chappell, bat-up is a "less efficient" method of batting and "it's probably the improvement in the bats that has allowed these [less efficient] methods to prosper, because the mishit goes better than it's ever gone before, so batsmen are probably not getting the feedback… that these methods are less efficient than methods that have been used before".

Graham Gooch was one of the early proponents of the bat-up method, which worked in English conditions © PA Photos

Chappell provides another reason why bat-up has become so popular: "Young batsmen using bats that are too heavy for them find it very difficult from the bat-down position because it's really hard to overcome inertia, to get started, so they feel that they need to get the bat up early." Justin Langer concurs: "When I was a kid, Kenny Meuleman used to make me use a two-pound-five or -six bat, it was so light. You look at some of these kids, they have got these big, heavy bats, it is a lot harder to pick it up and get rhythm". Langer reveals that up until around 2001 he "was [successfully] playing Test cricket and Shield cricket using two-pound-five or -six bats". Bradman, writing over half a century ago in The Art of Cricket, observed that "a good serviceable weight is about 2 lb. 4 ozs". Nowadays, the national chain of cricket stores that bears Greg Chappell's name doesn't even stock two-pound-five bats for sale!

Two other factors may have contributed to the rise of bat-up over the last decade. Cowan astutely points out that from "six, seven years ago, right until maybe two years ago, Shield wickets were very sporting and so people discovered that [bat-up] helped their game [in those conditions]".

It makes sense that in those green, English-style conditions, Australian batsmen would experiment with, and ultimately adopt, a technique that had been popularised by two successful English batsmen, Tony Greig and Graham Gooch. A bat-up technique helps a batsman achieve a basic level of competence in those conditions - because the bat is already up, the batsman can make a late decision to play or leave the ball, thereby accounting for late lateral movement. But the empirical evidence suggests that it may also hinder a batsman's ability to achieve mastery in them.

From 1989 to 2001, when Australian Test teams touring England featured batting line-ups composed entirely of bat-down batsmen (with the notable exception of Geoff Marsh in 1989), Australia comfortably won every Ashes series played in England. Since the mid-2000s, when bat-up batsmen started filtering into the Test XI, Australia have not won a single Ashes series in England. From 1989 to 2001, Australia's regular top six averaged 52.17 per batsman and scored 31 hundreds in 23 Tests. From 2005 to 2015, Australia's regular top six averaged 37.62 per batsman and scored 17 hundreds in 20 Tests.

Moreover, Chappell observes: "I've seen more low scores in top-level cricket in recent times than I've seen throughout my life because of that reason - [bat-up] batsmen are not able to change their position." That limitation, he explains, is exposed when the ball seams, swings or turns: see, for example, Australia's 60 at Trent Bridge in 2015, 131 in Hyderabad in 2013, 47 at Newlands in 2011, 98 at the MCG in 2010 and 88 at Headingley in 2010.

Two other factors may have contributed to the rise of bat-up over the last decade. Cowan astutely points out that from "six, seven years ago, right until maybe two years ago, Shield wickets were very sporting and so people discovered that [bat-up] helped their game [in those conditions]".

It makes sense that in those green, English-style conditions, Australian batsmen would experiment with, and ultimately adopt, a technique that had been popularised by two successful English batsmen, Tony Greig and Graham Gooch. A bat-up technique helps a batsman achieve a basic level of competence in those conditions - because the bat is already up, the batsman can make a late decision to play or leave the ball, thereby accounting for late lateral movement. But the empirical evidence suggests that it may also hinder a batsman's ability to achieve mastery in them.

From 1989 to 2001, when Australian Test teams touring England featured batting line-ups composed entirely of bat-down batsmen (with the notable exception of Geoff Marsh in 1989), Australia comfortably won every Ashes series played in England. Since the mid-2000s, when bat-up batsmen started filtering into the Test XI, Australia have not won a single Ashes series in England. From 1989 to 2001, Australia's regular top six averaged 52.17 per batsman and scored 31 hundreds in 23 Tests. From 2005 to 2015, Australia's regular top six averaged 37.62 per batsman and scored 17 hundreds in 20 Tests.

Moreover, Chappell observes: "I've seen more low scores in top-level cricket in recent times than I've seen throughout my life because of that reason - [bat-up] batsmen are not able to change their position." That limitation, he explains, is exposed when the ball seams, swings or turns: see, for example, Australia's 60 at Trent Bridge in 2015, 131 in Hyderabad in 2013, 47 at Newlands in 2011, 98 at the MCG in 2010 and 88 at Headingley in 2010.

99.94 reasons to go bat-down © Getty Images

One reason commonly - and incorrectly - cited for the rise of bat-up is the influence of elite-level coaches. It has been widely rumoured that Victoria's coaching staff, led by Greg Shipperd(the state's hugely successful head coach from January 2004 to March 2015), pushed batsmen into adopting bat-up. There is no truth to that rumour. What happened was this: Victorian players, starting with their young captain Cameron White in the mid-2000s, made the decision to go bat-up and then ran it by Shipperd and his coaching staff. Shipperd said that he and his staff were happy to respect the player's decision. "If that's the way you want to go, well, we'll coach around that as your preferred model."

Peter Handscomb - the 24-year-old Victoria batsman-keeper, one of the rising stars of Australian cricket - said that his original decision to start holding his bat up was made in around 2006-07 at the Victorian U-17s carnival at the suggestion of a coach. Handscomb was also "definitely" influenced by the success of batsmen such as Hussey, Kallis and Pietersen, who "were making runs and making it look easier with a bat-up approach".

For Handscomb and many other batsmen of the T20 generation, the bat-up method helps them to play "new shots in the game that weren't there 20 or 30-odd years ago… like reverse sweep, lap sweep, lap shot, basically anything reverse. If you have got your bat on the ground when the ball is released, then to get your bat up and then change and… try and hit the ball, it can almost be too long."

If anyone in Australian cricket has seen it all, it's 40-year-old Brad Hodge. The compact, classical batsman made his debut for Victoria as an 18-year-old in October 1993. And he is still playing - very successfully - all around the world as a T20 freelancer, in addition to working as an assistant coach with Adelaide Strikers. He is bat-down and has always been so, because that is what works for him, but cheerfully acknowledges that bat-up works for other batsmen such as Chris Gayle.

Many coaches fear that the proliferation of bat-up batsmen in the country could endanger the Australian style of aggressive, free-flowing batting © Getty Images

Hodge underlined a benefit of bat-down that Chappell mentioned too - "the feeling of your hands and the rest of your body moving through the ball". By contrast, the bat-up method can make a batsman more "robotic" - as he "rigidly pushes at the ball" - and make him lose that natural "feeling".

Langer, now the highly successful coach of Western Australia and Perth Scorchers, uses a similar word to describe the bat-up method: mechanical. "What often happens when you hold the bat up is that you [have] just got one plane to come down, so you are really stopping the ball, rather than having nice rhythm throughout the delivery". The problem with many mediocre bat-up batsmen is that they stand still and stiff in their stance, with their wrists fully cocked and their bat locked-in at the top of its bat-swing. This means that, like a marble statue of a batsman at the top of his backswing, they often limit themselves to one pre-selected swing plane.

The obvious strength of bat-up, as Cowan observes, is that it allows batsmen to "get a pretty regular [bat-swing]" that is "easy to replicate". But that strength is also the method's greatest flaw. Batting - in the words of two of Australia's greatest batsmen, Bradman and Chappell - is an "art", not a science. Picking the bat up from a neutral, bat-down position allows a batsman to wield his bat like an artist wields his paintbrush on a blank canvas - he can literally do anything with it, as he has an almost infinite variety of swing planes to choose from - whereas the rigid, bat-up batsman, with only a limited number of pre-selected swing planes available to him, often wields his bat like a robot on a factory assembly line.

Moreover, Hodge points out that the bat-down batsman's act of picking his bat up off the ground provides him with "fluid momentum" and natural power. That is particularly beneficial for a batsman like him with "a small stature" who cannot use brute force to muscle the ball over the rope. As his hands pick his bat up off the ground, and his feet move - in sync with his hands - out to the ball, he achieves what Langer lyrically describes as "that beautiful free-flowing fling" as the ball pings off the middle of his bat's sweet spot. This, according to proponents of bat-down, is the method's primary benefit. Chappell calls it "synchronisation". Langer calls it "having good footwork patterns" and "being relaxed at the crease". In the revised 1984 edition of The Art of Cricket, Bradman referred to it as the batsman's "coordination" of "the movements of his bat and feet", before swiftly declaring that he is "an opponent of the [bat-up] method".

Watch any successful bat-up batsman closely at the approximate point of release and one immediately notices that he employs a range of countermeasures to ameliorate the flaws of the bat-up method by effectively imitating the actions of a bat-down batsman. Langer highlights the "very loose" arms, "like a hose in a swimming pool", of the batsmen he admires who have successfully gone bat-up - Steven Smith, Hashim Amla, Katich and Phillip Hughes ("magnificent player he was, a beautiful player") - but concludes that, in his opinion, "the best way to get that relaxation in your shoulders and in your arms is to tap your bat". Chappell concurs and adds that by tapping his bat "subconsciously, the batsman is acting in time with the bowler's rhythm… getting into rhythm with the bowler… is a really important part of batting".

Australia's top seven in the 1990s and early 2000s all faced the bowler from neutral, bat-down positions, which allowed them to choose from a variety of swing planes © Getty Images

Other common countermeasures employed by bat-up batsmen include: wrists that are not cocked (Smith and Maxwell), bent knees (Smith and Handscomb), rocking hands down and up (Joe Root), and a preliminary bat-wiggle (Handscomb and Ben Stokes). Handscomb agrees to an extent with the argument that bat-up can adversely affect balance and synchronisation, but says:

"… there are ways to combat that and you can have your bat up and still be very, very, very balanced… if you watch a lot of batsmen that have bat up, just as the ball's released, there's always a little pre-movement or just something that changes it up and gets them into a strong position. For example, my bat's up but as the ball's coming down my bat goes back down and then back up again, so it's almost as if I've just picked it up off the ground."

Thus, it seems that in order for the bat-up method to work, the batsman must implement a range of countermeasures whose purpose is to imitate a bat-down batsman. That, essentially, is the point that Chappell is making when he describes bat-down as "the most efficient method".

In recent times, seasoned Australian batsmen, such as Cowan and Adam Voges, have substantially improved their performances by reverting to bat-down. Chappell and Langer both played a part in persuading Cowan to make the change. Langer was rather more blunt with his mate "Vogey", a man he respects and admires. "He'd been playing county cricket and he was batting like Graham Gooch with his left foot pointing down the wicket and I said, 'Mate, what the f*** are you doing?' He goes: 'Aw, I'll be in trouble [if I change now].' I said: 'Mate, nah, I'm not throwing you one more ball, I'm coach of Western Australia now, please start getting your stance right, start tapping again, mate, just get natural again.' Well, the rest is history."

Voges, after taking a season to bed down the technical change, put together two outstanding Shield summers, averaging 54.92and 104.46, to earn his Test cap at the age of 35. He proceeded to score a match-winning century on debut and was recently named the vice-captain of Australia for the eventually postponed Test tour of Bangladesh.

Two schools of thought have arisen in Australia in response to the spread of bat-up. The first, the freedom school, has no objection to kids experimenting with bat-up - but does not actively tell kids to go bat-up - because, as Shipperd explains, coaches like him believe that the decision belongs to the individual batsman. "We coach around that [decision], as opposed to fighting [it]." Shipperd and Woodhill - Steven Smith's highly respected junior coach, who currently works as David Warner's personal batting coach - belong to this school. Woodhill cautions that broad anti-bat-up pronouncements could hinder young batsmen establishing their own technique and we could "miss out on the more unusual superstar like a Steven Smith".

Comedown: Adam Voges returned to the bat-down method in 2012, and his subsequent prolific domestic seasons won him a Test cap at the age of 35 © Getty Images

The second school of thought, the Bradman-Chappell school, believes that the bat-up method, if used by kids, threatens the ability to produce truly Australian batsmen - that is, outstanding, free-flowing artists who destroy all types of bowling in all conditions - which, in turn, would threaten the ability to continue to play a distinctly Australian style of cricket - aggressive, attacking and winning. Accordingly, Chappell believes that Cricket Australia should adopt a "coherent policy" which explains to kids (and coaches) why bat-down is the most efficient way to learn to bat so that they have the opportunity - that "they've not been given in recent times" - "to experiment with the bat down".

Langer broadly agrees with Chappell's policy proposal. Ultimately the empirical evidence in favour of that policy is simply too persuasive. Plunkett compiled photographs and videos of Australia's top 15 Test and top 15 Shield run scorers at the approximate point of the bowler's release. Of those 29 great Australian batsmen (Langer appears on both lists), only two - Hussey and Chris Rogers - were bat-up.

It must be emphasised that the batsmen are categorised by reference to their position at the approximate point of the bowler's release. The great Australian batsmen did not all lift their bats at exactly the same point in time - there is, and has always been, a range of temporal lift points. At one end of the spectrum are Steve Waugh and Greg Chappell, who kept their bats grounded until just before the bowler released the ball. At the other end are Border and Michael Clarke, who lifted their bats relatively early - roughly when the fast bowlers jumped into their delivery stride. Border and Clarke are still categorised as bat-down, bat-tappers in Plunkett's data - because by tapping their bats as the bowler ran in to bowl and only lifting their bats at the approximate point of release, they accessed the substantive benefits of the bat-down method.

Cowan describes Plunkett's empirical evidence as compelling and acknowledges that "that's what brought me back to where I am now", which is bat-down, like he was as a kid. As Chappell points out, even those batsmen who have successfully gone bat-up as adults - for example, Hussey, Handscomb, Katich, Steven Smith, Kallis and AB de Villiers - learned the game as kids with their bats down.

Former Victoria coach Greg Shipperd was happy to allow his players to experiment with their batting stances, coaching around it, rather than fighting it © Getty Images

"There is," as the Australian novelist Thomas Keneally observed, "a divinity to our cricket", a divinity that ought to be preserved and nurtured in a time of uncertainty and change. If Chappell and Bradman are right, then that divinity - the very identity of the Australian cricket team, which hinges on their ability to play cricket the Australian way - is being imperilled by the proliferation of the bat-up method among children.

What began on the country's western seaboard more than a decade ago, as one Australian batsman's eminently sensible solution to a specific technical problem, has spread throughout our land like a virus, to the point where bat-up is now, arguably, the majority default approach in our junior ranks. The initial symptoms are purely cosmetic but make no mistake: if left untreated, the virus may threaten the very soul of Australian cricket. As Chappell put it:

"Australian cricket has survived on the back of outstanding players. I believe we have a responsibility to try and produce outstanding players, not mediocre to struggling players, players who are batting to survive. Most of the methods that I see that are being adopted by young batsmen are stopping them from ever becoming great players. That is a serious problem, in my opinion."

Tuesday, 16 June 2015

The menace of the last-wicket stand: Come in, No. 11!

Simon Barnes in Wisden India

It’s time to resurrect the Campaign for Real Number Elevens. We are in danger of losing touch with one of cricket’s most ancient traditions. One of the last Test series in England in which both teams included a classic No. 11 involved India, in 1990. And it was all the more inspiring for the contrast between them.

India had the leg-spinner Narendra Hirwani – a wee sleekit cow’rin tim’rous beastie of a batter, convinced that every ball was an explosive device best negotiated from square leg. In 17 Tests he scored 54 runs at 5.40. During that series, when India required 24 to save the follow-on at Lord’s, Kapil Dev launched Eddie Hemmings for four sixes in a row, rather than trust Hirwani to face a delivery. He was right, too: Hirwani fell first ball next over.

England countered with Devon Malcolm, a fast bowler convinced of his own immortality: a mighty, wide-shouldered swiper who never let his own poor eyesight – in his early days he played in Hank Marvin horn-rims – get in the way of his belief that every ball bowled to him belonged on the far side of the boundary. This approach brought him 236 runs in 40 Tests at 6.05.

But these guys are history. The contemporary No. 11 can bat. It’s not that every clown now wants to play Hamlet; they always did. These days, every clown can play the attendant lord, infinitely capable of swelling a progress, or starting a scene or two as circumstances require. As a result, the fall of the ninth wicket is no longer the signal to put the kettle on. The last-wicket stand used to be one of cricket’s brilliant jokes. Now it’s got serious.

In the First Test at Trent Bridge last summer, the Indian first innings concluded with a last-wicket stand worth 111, between Bhuvneshwar Kumar and Mohammed Shami. These days, though, substantial last-wicket stands come along like the No. 49 bus, and the next arrived one innings later, as Joe Root and Jimmy Anderson put on a Test-record 198; Anderson was disappointed when he got out for 81.

The previous year the Ashes had begun with Australia’s last-wicket stand of 163 – also at Trent Bridge, also a Test record – between Phillip Hughes and Ashton Agar. Agar, the No. 11, was out for 98; it turned out he was a far better batsman than bowler. And, in 2012, Denesh Ramdin and Tino Best hit 143 for the tenth wicket for West Indies at Edgbaston.

So let’s savour a few stats. In last summer’s England–India series, the average tenth-wicket stand was 38, higher than for any series of more than three matches. The previous-best was 33 – for the 2013 Ashes. The last wickets of England and India contributed 499 runs, another record; third, with 432, is the 2013 Ashes. Second and fourth in the list are the 1924-25 and 1894-95 Ashes, outliers from pre-history. The current numbers appear to indicate a trend – and 13 of the 26 last-wicket hundred stands have come this century.

A decent last-wicket stand is less of a surprise than it used to be. But its increasing regularity makes it even more irritating for the fielding side. It’s a combination of free runs and derisive mockery of the opposition. It’s a classic win double: the batting side feels better and better, while the bowling side feels ghastlier and ghastlier. It’s not as if someone has stolen an advantage: it’s more as if God Himself has taken sides.

It’s a time when the team that are more batted against than batting tend to lose their head. They start a bumper war; since these stands usually happen on flat pitches, that tends to be a doomed project. Or they try to get only one batsman out, which means that the man higher up the order can focus freely on scoring runs. And the longer the No. 11 stays in, the more capable he feels about looking after himself, and the more he can take annoying singles.

A terrible feeling gathers in the bowling side: this ought not to be happening. It’s a freak, and it’s freakishly unfair. In truth, it’s a freak no longer. The spectacle of tired bowlers running in on flat pitches to jubilant tailenders while infuriated fielders dive about in vain is becoming one of cricket’s staples.

This can be doubly difficult for the bowling side if the captain is an opening batsman, such as Alastair Cook for England: mentally preparing to bat at the drop of the next wicket, but unable to take that wicket, and unable to think with absolute clarity about how best to do so. It’s captaincy as a classic frustration dream: on a par with running for the train through a sea of treacle, or opening the exam paper and realising you don’t understand the questions, still less know the answers.

It’s not hard to work out how this has come about. Ever since the one-day game became part of cricket, bowlers regularly bat in important match situations. They know that, when it comes to selection between two bowlers of apparently equal merit, the nod goes to the better batsman. Bowlers work at batting. They have nets, they have coaches, they have batting buddies.

Meanwhile, protective equipment, especially the helmet, has made it much easier to be brave against fast bowling, while modern bat technology means that even mis-hits reach the boundary. And if this were not enough to tip things in favour of more and bigger last-wicket stands, the tendency to produce chief executives’ wickets has made these former oddities into statistical certainties. Three of those recent monster stands were at Trent Bridge; their pitch for the India match was rated “poor” by the ICC.

So among the general hilarity of the last-wicket stand – and they are gloriously funny to everyone not bowling or fielding at the time – there is a point that is serious, not to say sinister. It’s not just that tailenders have learned how to bat: it’s that the essential balance between bat and ball has made a significant shift.

It’s easier to bat and score runs than it has been at any time in the history of cricket. The proliferation of huge last-wicket stands indicates that something has gone seriously amiss. Take that England–India game at Trent Bridge. One can be regarded as good fortune. Two looks like misgovernment on a global scale.

It’s time to resurrect the Campaign for Real Number Elevens. We are in danger of losing touch with one of cricket’s most ancient traditions. One of the last Test series in England in which both teams included a classic No. 11 involved India, in 1990. And it was all the more inspiring for the contrast between them.

India had the leg-spinner Narendra Hirwani – a wee sleekit cow’rin tim’rous beastie of a batter, convinced that every ball was an explosive device best negotiated from square leg. In 17 Tests he scored 54 runs at 5.40. During that series, when India required 24 to save the follow-on at Lord’s, Kapil Dev launched Eddie Hemmings for four sixes in a row, rather than trust Hirwani to face a delivery. He was right, too: Hirwani fell first ball next over.

England countered with Devon Malcolm, a fast bowler convinced of his own immortality: a mighty, wide-shouldered swiper who never let his own poor eyesight – in his early days he played in Hank Marvin horn-rims – get in the way of his belief that every ball bowled to him belonged on the far side of the boundary. This approach brought him 236 runs in 40 Tests at 6.05.

But these guys are history. The contemporary No. 11 can bat. It’s not that every clown now wants to play Hamlet; they always did. These days, every clown can play the attendant lord, infinitely capable of swelling a progress, or starting a scene or two as circumstances require. As a result, the fall of the ninth wicket is no longer the signal to put the kettle on. The last-wicket stand used to be one of cricket’s brilliant jokes. Now it’s got serious.

In the First Test at Trent Bridge last summer, the Indian first innings concluded with a last-wicket stand worth 111, between Bhuvneshwar Kumar and Mohammed Shami. These days, though, substantial last-wicket stands come along like the No. 49 bus, and the next arrived one innings later, as Joe Root and Jimmy Anderson put on a Test-record 198; Anderson was disappointed when he got out for 81.

The previous year the Ashes had begun with Australia’s last-wicket stand of 163 – also at Trent Bridge, also a Test record – between Phillip Hughes and Ashton Agar. Agar, the No. 11, was out for 98; it turned out he was a far better batsman than bowler. And, in 2012, Denesh Ramdin and Tino Best hit 143 for the tenth wicket for West Indies at Edgbaston.

So let’s savour a few stats. In last summer’s England–India series, the average tenth-wicket stand was 38, higher than for any series of more than three matches. The previous-best was 33 – for the 2013 Ashes. The last wickets of England and India contributed 499 runs, another record; third, with 432, is the 2013 Ashes. Second and fourth in the list are the 1924-25 and 1894-95 Ashes, outliers from pre-history. The current numbers appear to indicate a trend – and 13 of the 26 last-wicket hundred stands have come this century.

A decent last-wicket stand is less of a surprise than it used to be. But its increasing regularity makes it even more irritating for the fielding side. It’s a combination of free runs and derisive mockery of the opposition. It’s a classic win double: the batting side feels better and better, while the bowling side feels ghastlier and ghastlier. It’s not as if someone has stolen an advantage: it’s more as if God Himself has taken sides.

It’s a time when the team that are more batted against than batting tend to lose their head. They start a bumper war; since these stands usually happen on flat pitches, that tends to be a doomed project. Or they try to get only one batsman out, which means that the man higher up the order can focus freely on scoring runs. And the longer the No. 11 stays in, the more capable he feels about looking after himself, and the more he can take annoying singles.

A terrible feeling gathers in the bowling side: this ought not to be happening. It’s a freak, and it’s freakishly unfair. In truth, it’s a freak no longer. The spectacle of tired bowlers running in on flat pitches to jubilant tailenders while infuriated fielders dive about in vain is becoming one of cricket’s staples.

This can be doubly difficult for the bowling side if the captain is an opening batsman, such as Alastair Cook for England: mentally preparing to bat at the drop of the next wicket, but unable to take that wicket, and unable to think with absolute clarity about how best to do so. It’s captaincy as a classic frustration dream: on a par with running for the train through a sea of treacle, or opening the exam paper and realising you don’t understand the questions, still less know the answers.

It’s not hard to work out how this has come about. Ever since the one-day game became part of cricket, bowlers regularly bat in important match situations. They know that, when it comes to selection between two bowlers of apparently equal merit, the nod goes to the better batsman. Bowlers work at batting. They have nets, they have coaches, they have batting buddies.

Meanwhile, protective equipment, especially the helmet, has made it much easier to be brave against fast bowling, while modern bat technology means that even mis-hits reach the boundary. And if this were not enough to tip things in favour of more and bigger last-wicket stands, the tendency to produce chief executives’ wickets has made these former oddities into statistical certainties. Three of those recent monster stands were at Trent Bridge; their pitch for the India match was rated “poor” by the ICC.

So among the general hilarity of the last-wicket stand – and they are gloriously funny to everyone not bowling or fielding at the time – there is a point that is serious, not to say sinister. It’s not just that tailenders have learned how to bat: it’s that the essential balance between bat and ball has made a significant shift.

It’s easier to bat and score runs than it has been at any time in the history of cricket. The proliferation of huge last-wicket stands indicates that something has gone seriously amiss. Take that England–India game at Trent Bridge. One can be regarded as good fortune. Two looks like misgovernment on a global scale.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)