'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label industry. Show all posts

Showing posts with label industry. Show all posts

Thursday, 22 December 2022

Tuesday, 20 December 2022

Monday, 20 December 2021

Sunday, 21 July 2013

Ignore the hype: Britain's 'recovery' is a fantasy that hides our weakness

A tiny rise in GDP is nothing to celebrate while the UK economy is as dysfunctional as ever

A rise in GDP will be celebrated as proof of George Osborne's wisdom – but the dysfunctions of the UK economy are still firmly in place. Photograph: Rex Features

Next Thursday we will get a further taste of what it is like living in an one-party state. The estimate for GDP growth in the second quarter will be published – predicted to rise between 0.2% and 0.3%, confirmation that a triple dip recession has been avoided and the economy is on the mend. Expect an over-the-top reaction from our centre-right media.

George Osborne's sagacity will be lauded to the skies, and scorn poured on all those who have criticised economic policy or worried about Britain's economic structures. It will be another chance to swing opinion behind the Conservative party – all the more effective because the coverage will reproduce the co-ordination of a government propaganda machine without any formal instruction being given.

Economies are like corks. They have inbuilt upward momentum driven by productivity and population growth. That momentum can be reversed for 18 months or two years in a typical recession when investment and consumption have run ahead of themselves, and of necessity fall back. But like a cork the economy will eventually bounce back to the surface – where it would have been had the recession not happened.

What we are witnessing is that natural bounce – but very weak, extraordinarily slow and no prospect of any substantive follow-through once the economy returns to 2008 levels of output some time next year. What usually takes no more than two years will have taken six – the slowest recovery for more than a century. Exports are effectively unchanged, even to faster growing non-EU countries, despite a 25% devaluation. Company investment has collapsed by 34%. Real wages are 9% below their peak – they rose in every other postwar recession – and are set to fall further. The profound dysfunctions of the British economy, despite wild claims otherwise, remain firmly in place.

What is so dismaying is that hopes that investment and exports would lead recovery have been completely dashed. Instead the British are returning to what they are best at – running down their savings and borrowing enormous mortgages, partially guaranteed by the state under the Help to Buy scheme, to force up house prices.

I did not join the chorus of criticism of Help to Buy when it was launched: it was a clever, time-limited Keynesian use of the public balance sheet to support a distressed part of the economy, and no recovery is conceivable without some rise in house prices rekindling animal spirits and lifting confidence. What was wrong was: to superimpose it upon a market that privileges buyers who want to let rather than own; the Treasury vetoing an extension to lending to business in general; and not recognising that the same Keynesian thinking is needed across the board.

What takes me aback is the determined way the national conversation is skewed towards the inadequacies of the public sector, however concerning – avoidable deaths in the NHS or extravagant pay-offs for BBC executives – without any parallel focus on the inadequacies of the private. The Coronation festival for the Queen was meant to be a celebration of British innovation. Yet there were only three large company pavilions in the Palace gardens – GSK, Bentley and Jaguar Land Rover (owned by the Indian Tata) – and a host of tiny companies dealing in niche luxury goods. The contrast with the industrial and innovative power that could have been mobilised when she began her reign 60 years ago is painful.

Moreover, back then, economic power would have been drawn more equally across the country. There were certainly regional imbalances in the 1950s but compared with today they were trivial. Outside London and the south-east there was no private sector job creation in the decade to 2008. Today these regions possess little more than what Karel Williams of the Centre for Research on Socio-Cultural Change calls a "foundation economy" – the structures that deliver the likes of electricity, food and hospital care but with virtually no private sector entrepreneurial activity. The average size of a British-owned manufacturing company in the regions, he says, is 14 – subcontracting workshops and downmarket complements to those niche luxury companies.

The problem is too few of either develop into companies of any scale. Their owners are too transactional, unsupported or plain greedy, and the financial system that supports them too fickle, disengaged and commission-hungry. Almost no new major British companies have emerged over the past 20 years while dozens that have taken decades to grow have been assimilated into global multinationals, their strategies dictated outside Britain. Some, of course, make a vital contribution to our economy. But this is no basis on which to launch anything but a fitful recovery and weak investment. Yet no fundamental questions are asked.

Instead the Conservative party, and the commentators who support it, live in Fantasy UK, in which the problem is regulation and the EU. The first initiative of David Cameron's new business team in Downing Street has been to ask British businesses to identify those EU regulations most hindering British growth. I conducted my own straw poll in London's Tech City. Brussels and the EU were simply not on the radar. Instead the list included the financial system's aversion to risk, immigration controls keeping out talented foreigners, and BT's inability to provide high-speed broadband.

The debate has to change. Companies in Britain – domestic or foreign-owned – need the prospect of a sustained growth of demand. The governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, hinted at establishing a target for growth and inflation combined – nominal GDP – but was beaten back by the austerity defenders. He should stick to his guns. We have to create ownership and financing structures – scaling up the proposed Business Bank fast — that permit companies to grow and stay owned, as far as possible, in Britain. We have to get fundamentally serious about infrastructure. The LSE growth commission's proposal for an interlocking system of infrastructure strategy board, infrastructure bank and independent planning commission is a good starting point. The housing market needs root and branch reform. Above all, there has to be a sense of mobilisation.

But instead we have nonsense babble about the EU being all that is holding us back; huge prizes for essays on EU exit as a focus for intellectual effort (courtesy of the Institution of Economic Affairs); and endless nostalgic festivals and celebrations about world wars one and two. Welcome to Fantasy UK.

Sunday, 7 October 2012

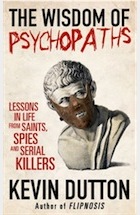

A convincing study shows that business leaders and serial killers share a mindset

The Wisdom of Psychopaths by Kevin Dutton – review

Christian Bale as Patrick Bateman in the 2000 film adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis’s novel American Psycho. Photograph: Moviestore Collection/Rex

Do you think like a psychopath? It has been claimed that one quick way of telling is to read the following story and see what answer to its final question first pops into your head:

- The Wisdom of Psychopaths

- by Kevin Dutton

- Buy it from the Guardian bookshop

- Tell us what you think: Star-rate and review this book

While attending her mother's funeral, a woman meets a man she's never seen before. She quickly believes him to be her soulmate and falls head over heels. But she forgets to ask for his number, and when the wake is over, try as she might, she can't track him down. A few days later she murders her sister. Why?

If the first answer that springs to your mind is some variation of jealousy and revenge – she discovers her sister has been seeing the man behind her back – then you are in the clear. But if your first response to this puzzle is "because she was hoping the man would turn up to her sister's funeral as well", then by some accounts you have the qualities that might qualify you to be a cold-blooded killer – or a captain of industry, a nerveless surgeon, a recruit for the SAS – or which may well make you a commission-rich salesman, a winning barrister, a charismatic clergyman or a red-top journalist. The little parable purports to reveal those qualities – an absence of emotion in decision making, a cold focus on outcomes, an extremely ruthless and egocentric logic – which tend to show up in disproportionate degrees in all those individuals.

There is a problem though. When Kevin Dutton, the author of this compulsive quest into the psychopathic mind, tried the question on some real psychopaths, not one of them came up with the "second funeral" motive. As one commented: "I might be nuts but I'm not stupid."

The admirable quality of this book is Dutton's refusal to accept easy answers in one of the more sensational fields of popular psychology. He comes at the challenge of deconstructing the advantages and dangers of psychopathic behaviour with two distinct motivations. First, the academic rigour of a research fellow at Magdalen College, Oxford. Second, with the more human need to understand the character of his late father, a market trader in the East End, a man with an "uncanny knack of getting exactly what he wanted", who could sell anything to anybody, because to him "there were no such things as clouds, only silver linings". Psychopaths, we learn, are the ultimate optimists; they always think things will work in their favour.

Dutton's curiosity takes him from boardrooms and law courts to neurological labs. He tries in different ways to get inside the heads of those individuals for whom killing has been a way of life – from Bravo Two Zero's Andy McNab to the video game-obsessed inmates of Broadmoor's secure wards. In his effort to get to their truths he has a tendency to write with the one-tone-fits-all breeziness of the excited enthusiast; at certain points his insistent chattiness jars. Though he demonstrates few of the characteristics of psychopaths himself, none of the limited range of cold fury of Viking "berserkers" or the wilful icy detachment of brain surgeons, he is in thrall to their possibilities. Perhaps, he argues, we all are.

Dutton's book at any rate supports the idea that to thrive a society needs its share of psychopaths – about 10%. It not only shows the value of the emotionally detached mind in bomb disposal but also the uses of the psychopath's ability to intuit anxiety as demonstrated by, for example, customs officials. Along the way his analysis tends to reinforce the idea that the chemistry of megalomania which characterises the psychopathic criminal mind is a close cousin to the set of traits often best rewarded by capitalism. Dutton draws on a 2005 study that compared the profiles of business leaders with those of hospitalised criminals to reveal that a number of psychopathic attributes were arguably more common in the boardroom than the padded cell: notably superficial charm, egocentricity, independence and restricted focus. The key difference was that the MBAs and CEOs were encouraged to exhibit these qualities in social rather than antisocial contexts.

As Dutton details this relationship, part of you is left wondering if the judge who recently praised a housebreaker for his courage and resourcefulness, and expressed the hope that in the future he might use his energies in more constructive directions, might have had Dutton's book by his bedside. Certainly you are left wondering if corporations that really want to find driven leaders might be as well to conduct their recruitment round in the juvenile courts as the universities. In this sense it is hard to know which is more chilling: the scene in which Dutton weighs a serial killer's brain in his hands and reveals it to be in no way tangibly different from yours or mine, or the research that shows the ability of American college students to empathise with others has, in the past 30 years, reduced by 40%…

Sunday, 1 July 2012

New-tech moguls: the modern robber barons?

Are today's captains of industry – the wealthy and powerful figures who control the digital universe – any different from the ruthless corporate figures of the past?

From left: Co-founders of Google Larry Page and Sergey Brin, Chairman and CEO of Dell Michael Dell, Co-founder of Microsoft Bill Gates, and Chairman and CEO of Facebook Mark Zuckerberg Photographs: AP; Getty

Here's an interesting fact: 10 of the people on Forbes magazine's tally of the world's 100 richest billionaires made their money from computer and/or network technology. At the top (second on the list) is Bill Gates, co-founder of Microsoft, whose net worth is estimated by Forbes at $61bn, despite the fact that he continues to try to give it away. Gates is followed by Larry Ellison, boss of Oracle, with $36bn, and Michael Bloombergwith $22bn. Larry Page and Sergey Brin – co-founders of Google – occupy joint 24th place with $18.7bn each. Jeff Bezos of Amazon is No 26 with $18.4bn while the newly enriched Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook sits at No 35 with £17.5bn. Michael Dell, founder of the eponymous computer manufacturer, is at No 41 with $15.9bn while Steve Ballmer, Microsoft's CEO, is three places lower on $15.7bn and Paul Allen – co-founder of Microsoft – brings up the rear at No 48 with a mere $14.2bn. Steve Jobs, who was worth about $9bn when he died, doesn't even figure.

What's striking about this is not just the staggering wealth that these people have managed to squeeze out of what are, after all, just binary digits (ones and zeros), but how recent are the origins of their good fortunes. Mark Zuckerberg, for example, went from zero to $17.5bn in less than eight years. Microsoft – the company that has propelled Gates, Ballmer and Allen into the Forbes pantheon – dates only from 1975. Oracle was founded in 1977. Bloomberg turned a $10m redundancy cheque from Salomon Brothers into his personal money-pump in 1982. Dell started making computers in his university dorm in 1984. Bezos launched Amazon with his own savings in 1995. Brin and Page turned their PhD research into a company called Google in 1998. And Zuckerberg launched Facebook in 2004.

For some of these people, great wealth is correlated with significant power. Once Microsoft captured the market for PC operating systems and office software, Bill Gates and co ruthlessly leveraged their monopoly to eliminate rivals (remember Netscape?) and dictate pricing. So we got a world where you could have any kind of computer you wanted, provided it ran Microsoft Windows. In the era when the PC was the computer, Bill Gates was king because he controlled the PC.

But although Microsoft remains a significant force, its power waned as computing moved from the PC to the network – and therefore to the people and companies who dominate that. Step forward the Google boys, who have the power to render any website virtually invisible, because if their algorithms decide not to index a site then effectively it ceases to exist – at least in cyberspace. Their computers also read our mail and store our documents. Google dominates the online advertising business. The company's founders say grandly that their mission is "to organise the world's information" – and they mean it. They have already digitised a significant amount of the world's printed books – although they are not yet authorised to make many of them available online. And Google's cars have photographed every street in the industrialised world.

Meanwhile, in another part of the jungle, Amazon's Bezos is not just vaporising bricks-and-mortar bookstores; he's also on his way to becoming the world's biggest publisher. And he's already the world's largest online retailer – the Walmart of the web. In social networking Mark Zuckerberg has cunningly inserted himself (via his hardware and software) into every online communication that passes between his 900 million subscribers, to the point where Facebook probably knows that two people are about to have an affair before they do. And because of the nature of networks, if we're not careful we could wind up with a series of winners who took all: one global bookstore; one social network; one search engine; one online multimedia store and so on.

There was a time when the power exercised by computer and internet companies seemed a matter of relatively esoteric concern. But as digital technology began to pervade our daily lives, the boundary between the "real" world ("meatspace", as geeks used to call it) and cyberspace began to blur. What happened in the latter suddenly mattered in the former – and not just in Tunisia and Egypt either. Think of the way Steve Jobs's creation – Apple – exercises such dominance over online music, smartphones and tablet computers. Or ponder what Google and Facebook now know about our lives, loves and obsessions. Or what Amazon knows about our consumption patterns. The implication is that cyberpower has correlates in the real world, which means that it's time we had a really good look at those who wield it. What are these masters of the digital universe really like? What are their values and their politics? And are they any different from the corporate moguls of the past?

Given their prominence, we know surprisingly little about our modern moguls – for various reasons. One is that we are remarkably incurious about what makes them tick. We focus instead on the fact that one of them (Zuckerberg) wears a hoodie even when being interviewed by investment bankers; or that Larry Page, co-founder of Google, refused to stop using his laptop when a big media mogul came to talk to him; or that Bill Gates used to rock furiously backwards and forwards in a rocking chair when being interviewed for an anti-trust case; or that Steve Jobs drove a comparatively modest sports car and lived in a small, old-fashioned house rather than the postmodern minimalist palace that many people would have predicted.

But this is all superficial stuff, the journalistic fluff of celebrity profiles and gossip columns. What's much more significant about these moguls is that they share a mindset that renders them blind to the untidiness and contradictions of life, not to mention the fears and anxieties of lesser beings. They are technocrats who cleave to a worldview that holds that if something is technically possible then it should be done. How about digitising all the books in the world? No problem: you just throw resources and technology at the task. And if publishers protest about infringement of copyright andauthors moan about their moral rights, well, that just shows how antediluvian they are. Or how about photographing every street in Europe, or even the world? Again, no problem: it's technically feasible, after all. And if Germans object to the resulting intrusion on their privacy, well let them complain and we'll pixelate the sods. Oh – and when we discover that those same cars have been hoovering up the details of our home Wi-Fi networks, their bosses say "Oops! Sorry: it was a mistake." Same story with the high-resolution satellite imagery beloved of Google and – now – Apple. Same story with Mark Zuckerberg's fanatical, almost sociopathic, belief that the default setting for life should be "public" rather than "private". The prevailing technocratic motto is: if something can be done, then it ought to be done. It's all about progress, stoopid.

Actually, it's all about values. And money. The trouble is that technocrats don't do values. They just do rationality. They love good design, efficiency, elegance – and profits. That's why one of the poster children of the industry is Apple's creative genius, Jonathan Ive, who designs beautiful kit in California which is then assembled in Chinese factories. And when the execrable working conditions prevalent in such places are exposed, the company's senior executives profess themselves surprised and appalled and resolve to do everything they can to ameliorate things. And we believe them – and continue eagerly to purchase the gizmos manufactured in such oppressive plants.

Why are we so credulous, so forgiving? It's partly because wealth – like political power – is a powerful aphrodisiac. But it's mainly because we accept these people at their own valuation. We've bought into their narrative. They see themselves as progressives, as folks who want to make the world a better, more efficient, more rational place. We're charmed by their corporate mantras – for example "Don't be evil" (Google) or "Move fast and break things" (Facebook). In their black turtlenecks and faded jeans they don't seem to have anything in common with Rupert Murdoch or the grim-faced, silk-hatted capitalist bosses of old. Instead of grinding the faces of the poor, our modern technology magnates move effortlessly from tech forums to TED to All Things D to Davos, reclining on spotlit sofas discussing APIs and cloud computing with respectful or admiring moderators. And in recent times, they are even invited to lunch with President Obamaor as guests at political summits where they are fawned upon by presidents and prime ministers who hope that some of the magic dust will rub off on them.

What gets lost in the reality distortion field that surrounds these technology moguls is that, in the end, they are fanatically ambitious, competitive capitalists. They may look cool and have soothing bedside manners, but in the end these guys are in business not just to make money, but to establish sprawling, quasi-monopolistic commercial empires. And they will do whatever it takes to achieve those ambitions.

The strongest link that binds them is that they are all pioneers in the exploitation of virgin territory, and that rings some historical bells. When the internet first exploded into public consciousness in the 1990s as a result of the web, many observers were reminded of what happened in the United States after the end of the civil war in 1865. Then, there was an exciting sense of a continent to be explored, gold and mineral resources to be discovered and exploited, land for anyone who was prepared to work it, industries to be founded, opportunities galore. What then followed was an explosion of speculative investment, led by railway companies which – as Anthony Trollope shrewdly observed on a visit to the US – "were in fact companies combined for the purchase of land… looking to increase the value of it fivefold by the opening of the railroad."

Thus began the era satirised by Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner in their novelThe Gilded Age: A Tale of Today, which was published in 1873. Twain and Warner were struck by the rampant greed and speculative frenzy of the times – not to mention its pervasive political corruption. But in that febrile milieu a smallish group of ingenious, ruthless and visionary entrepreneurs created a modern industrial state. Leland Stanford, EH Harriman, Jay Gould, Charles Crocker, Henry Plant, Henry Flagler, Cornelius Vanderbilt and Charles Yerkes built railways; John D Rockefeller created Standard Oil and brought his distinctive brand of oligopolistic order to the oil business, eventually controlling 90% of the industry; Andrew Carnegie, Henry Frick and Charles Schwab created a vast steel industry; and bankers such as JP Morgan, Joseph Seligman, Andrew Mellon and Jay Cooke organised the finance that funded these huge ventures.

In addition to building a modern industrial state, these gents amassed huge fortunes for themselves using a raft of dubious techniques, including fraud, stock-dilution, the bribing of corrupt politicians, the creation of secret cartels (ironically called "trusts") and the ruthless exploitation of poorly paid, non-unionised workers – which is why Matthew Josephson dubbed them "robber barons" in his book of the same title. In the end, their abuses and excesses led to a legislative backlash in the form of the 1890 Sherman Anti-Trust Act, the first federal statute to limit cartels and monopolies, and to a more general public revulsion ushered in by Theodore Roosevelt's presidency in 1901. In the twilight of their lives, some of the barons (for example Carnegie, Mellon and Frick) sought to acquire public respectability – or perhaps bargaining chips for negotiating with the Almighty – by endowing charitable foundations and eponymous museums, and engaging in other public-spirited enterprises.

In comparison with these monsters of the gilded age, our contemporary moguls – Gates, Page, Brin, Ellison, Bezos et al – may look rather tame. They appear, for example, to be much more law-abiding than their 19th-century counterparts; or at any rate they have had much less success in bending lawmakers to their will. In fact, compared with the skills of the entertainment industry in suborning members of the US Congress, the technology magnates are the merest amateurs – which is why the legislators were so astonished by the industry's vigorous reaction to Sopa, the Stop Online Piracy Act. The thought that the technology industry might actually have teeth had never previously occurred to the denizens of Capitol Hill.

We should also remember that the world in which Microsoft, Oracle, Google and Amazon operate is radically different in one important respect. The stage on which Rockefeller, Carnegie, Vanderbilt and their contemporaries strutted was predominately a national one: most of their enterprises and ambitions spanned only the continental United States, whereas the big technology companies of our day are transnational corporations that operate in a variety of different cultures and legal jurisdictions. John D Rockefeller just had to worry about fixing American officials and politicians; Larry Page, Google's CEO, has to deal not only with the US Department of Justice, but also with the European Commission, the Chinese government and Vladimir Putin's goons.

There are also radical differences in the kinds of industrial empires that the two classes of magnate have created. The 19th-century entrepreneurs built huge companies, conglomerates and cartels. They employed millions of people, operated huge plants and equipment (railways, shipping, iron and steel mills, oil refineries) and made an indelible imprint on the landscape. To use a contemporary cliche, they "shipped atoms" – physical objects. With the exception of Amazon and Apple, their modern counterparts, in contrast, are mainly in the business of shipping bits – in the form of software and online services. Despite the bleating of their PR departments, they are not huge primary employers. Google, for example, has only about 33,000 employees worldwide. And often the only tangible, physical sign of their presence and scale is the huge server farms that power their operations and which do have a significant impact on the environment – not to mention the landscape in the places where they are located.

But just because our contemporary moguls don't gouge minerals from the earth, run blast furnaces or operate oil refineries doesn't mean that their growing empires aren't real. To the physical economy created by Carnegie and co, digital technology has added a whole new economy based on information goods – nowadays embodied as ones and zeros – which may turn out to be at least as pervasive and valuable. We still make cars using steel, rubber and plastics, for example, but the value of the electronics in their engine management units and braking-control systems already exceeds the value of the vehicles' physical components. And this pattern will increasingly be replicated in other areas of economic life.

So the fact that one cannot see the information goods that Google and co gather, store, disseminate and control doesn't mean that those goods aren't real and valuable. To take just one example, Facebook now owns and controls a virtual space that will soon contain more people than the entire Indian subcontinent. Those merry throngs may delude themselves that they are cavorting in a public place. But in reality they are gathering in Master Zuckerberg's shopping mall – a fact that potentially gives him a reach and power that would make any robber baron green with envy.

Sceptics will point out that when one puts our masters of the digital universe in a historical context they aren't as rich or as important as we currently imagine. Last year, for example, Forbes commissioned an economist to come up with an inflation-adjusted list of the richest Americans of all time, and the website Business Insider published the results. The list is headed by those grizzled old robber barons, John D Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie and Cornelius Vanderbilt, with $336bn, $309bn and $185bn respectively. The only contemporary figure who makes it on to the list is Bill Gates, whose net worth at its peak was estimated at $136bn – which (says the sceptic) rather puts Larry Ellison, the Google boys and Jeff Bezos into perspective.

Bubble punctured, then? Not quite. It could be that the reason Bill Gates makes it on to the inflation-adjusted list is simply that he's been around the longest. Microsoft, remember, dates from 1975 – 37 years ago. Facebook has only been going since 2004. Who knows where Zuckerberg and the Google boys will be in 2041? The digital economy has a lot more growth left in it. As Churchill might have said, we haven't yet reached even the end of the beginning.

But perhaps the most intriguing question about these two different groups of industrial magnates concerns their legacies. The industries and enterprises founded by the robber barons of the 19th century still endure – though in some cases (steel, for example) the action has moved to Asia and parts of the developing world. What, one wonders, will endure of Google, Facebook, Oracle and Amazon? And what will be their founders' legacies? And here we get a clue from the robber barons of the 19th century. Many years after their deaths we still recognise the names of John D Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie. Will Zuckerberg and Page enjoy the same level of name-recognition among our great-great-grandchildren?

The answer may well depend not on how much money they make, but how much they give away. After all, the way their 19th-century counterparts live on is in the charitable foundations they established – the Rockefeller Foundation, set up in 1913, and theCarnegie Corporation of New York, founded in 1911. And here at least we do have a contemporary mogul who is way ahead of the pack. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, with assets of $37.4bn, is the world's largest charitable trust.

Tuesday, 10 January 2012

The cost of our habits

By Ardeshir Ommani

Altria Group is the leading cigarette maker in the United States. The stock of the company rose 20% in 2011's depressed markets and it's up 50% over the past two years, nearly four times the market's average gain. About two weeks ago, the stock of the company, which is the parent of Philip Morris USA and that of the Marlboro brand hit a 52-week high of $36.40.

The rise in its stock price is influenced by the company's stable cash flow and a dividend yield of 5.5%. At the time when money market rates are less than 0.5%, and the 10-year Treasury is

yielding less than 2%, the stocks of Altria Group attracts all the attention of the investors who do not ask how many smokers would die this year because of addiction and succumbing to lung cancer. It is worth noting that on December 23, 2011, from Richmond, Virginia, Altria's operating companies launched "Citizens for Tobacco Rights", a nation-wide website to assist the tobacco companies in promoting lowering taxes on cigarette sales.

Although US cigarette sales have been in a severe long-term decline, to be exact, its shipments dropped by a third over the past 10 years, the industry has been able to offset the volume decline with increases in wholesale prices. Naturally after addicting a large segment of the youth around the world, the owners of Altria Corporation are led to raise the cost of their habits and suffering.

The companies have raised cigarette prices by nearly 35% over the past 10 years, even as smokers shouldered huge jumps in federal and state cigarette taxes. Altogether retail prices and additional taxes hiked the cost of a pack to $5.95. This was more than double the rise in overall consumer prices.

This shows that the high rates of profitability in addictive substances is the ideal method of exploiting not only the workers, but also the consumers. The change in the demographics of cigarette addicts has forced the industry to intensify the rate of exploitation of those who can least afford the habit in a long period of economic stress and high rates of unemployment.

The captains of the stock market seem unshaken. The stocks look rich based on their double-digit price per earning ratios. The high rates of profitability in the industry have led the management to implement the strategy of stock buybacks and huge stock awards for management compensation.

Altria is by far the biggest US cigarette maker in both market weight ($61 billion ) and revenue-wise (over $16 billion a year). A substantial share of the company profits are generated outside the US. Philip Morris International, a subsidiary of Altria, sells Philip Morris brand lineups in about 180 countries around the world.

In other words, the men, women and more frequently, elementary-aged children - often at the cost of their lives - are providing these gentlemen in New York and Chicago with lavish life-styles. (Looking at just a few of the advertisements in major corporate newspapers as the Financial Times, New York Times, The Telegraph, etc. directed at this wealthy 1%, we see a woman's handbag selling for $4,000).

In 2009, Altria purchased the smokeless-tobacco producer UST, which makes Copenhagen and Skoal brands at the cost of $11.7 billion. The reason Altria shouldered such a high cost price is that smokeless tobacco is a much-less regulated part of the worldwide cigarette market. Lack of regulations leaves the smokers at the mercy of the tobacco industry. Altria generates in an average $3.5 billion a year in cash flow, most of which ends in the investor's bank accounts in the form of dividends and interests and conspicuous consumption.

As a group, cigarette smokers have lower household incomes than non-smokers and are nearly twice as likely to be unemployed, says a financial officer of Morgan Stanley, a banking corporation. Studies have shown that in communities with higher economic status, its members send their children to better-financed public schools and private universities where environmental sciences and healthier life-styles are emphasized in the educational curriculum from early grade school through university level.

Anti-smoking campaigns partially financed by higher city and state budgets are more predominant on expensive billboards in these higher income communities.

On average a member of this lower economic class spends more than $2,000 annually, smoking a pack a day, the amount that could be allocated towards the present and future sustenance. Smokers, in their attempts to halt casting a large amount of money to the rich, many have traded down to either cheaper cigarettes or bulk tobacco for rolling their own cigarettes.

For this reason, shipments of roll-your-own and pipe tobacco jumped 30% in the first half of 2011. In the brave new world, particularly the Facebook generation age 21 through 29 is no longer fascinated with that rugged cowboy who was for many decades the symbol of Marlboro.

Alongside Altria in the tobacco market stand such giants as Reynolds American, maker of Camel and Pall Mall as well as Natural Spirit brands selling the ugly and more hazardous chewing tobacco brands. To entice new smokers or keep the old ones in the loop, the cigarette companies constantly hatch out new names with new packets. Recently, Philip Morris USA came up with what it calls the "Marlboro Leadership Program" which puts a price cap on what the retailers can charge for a pack of Marlboro in return for promotional incentives, such as a free pack for every carton sold.

While in the US, after years of public pressure, the federal and state governments have imposed some restrictions on advertising and marketing tobacco products, the same companies in the markets of the developing countries promote and glamorize smoking among school children, going so far as to distribute free packs of cigarettes along the pathways leading to schools, the way they did just a few decades ago in the run-down parts of the big cities and the depressed small towns across the US.

Also, the ruling classes of the countries whose economies are dependent on the US and its partners benefit from such relations through providing lucrative markets for the tobacco products of the major international cigarette producers.

It is telling that the gains posted by these tobacco companies in 2011 was skyrocketing when few other stocks were thriving last year. A group of mutual fund managers who tried to avoid negative performance by the end of the year resorted to placing the shares of several tobacco firms among their top holdings.

Gains of more than 20% among the addiction enablers helped these funds outperform their rivals and attracted the moderate savings and the retirement funds of the employed and retired working class. Such is the political economy of the habit-forming industry, addiction of the oppressed and higher rates of profitability.

Ardeshir Ommani is a writer on issues of war, peace, US foreign policy and economic issues. He has two Masters Degrees in the fields of Political Economy and Mathematics Education.

Sunday, 8 January 2012

Germany once admired British workmanship – but that was a long time ago

Over the North Sea lies the richest country in Europe, its success built on the manufacturing industry that Britain has spurned

'The war hadn't been over 10 years and somehow Germany was making model trains more convincing than our own'

We all want to be Germans now: to make, to sell and not to yield. We would like to earn some respect, not least self-respect, and have some idea of our national future. The UK will never replace Germany as the world's second largest exporter, but we can surely manage to manufacture a few more things and "rebalance the economy", as the saying goes, to shrink the influence of the City of London.

So many people have had this dream recently – Vince Cable, of course, and Lord Glasman, no doubt, but also George Osborne when he made his fatuous speech about the "march of the makers". And there over the North Sea is the richest country in Europe: exemplary Germany, with its technical schools and apprenticeships, its respect for engineers, and its layer of family businesses known as the Mittelstand that puts long-term reputation above short-term profit by making the specialised parts that industry everywhere needs. How foolish we were to imagine that national prosperity could be spun from figures on a computer screen, out of thin air. How silly to despise the making of three-dimensional objects as a lowly process that had quit the west for the east. And how wise it would be (so the dream goes) to take a leaf from Germany's book and make manufacturing a much larger slice of the economy, therefore returning Britain to an earlier and possibly more solid version of itself.

That self is a long time ago. I remember watching Edgar Reitz's long and haunting film Heimat in the mid 1980s. Through the life of one family, the history of Germany in the 20th century was related in all its difficulty. At one point in the second world war, two characters find part of an aircraft or a bomb (I can't recall which) in a field. "Look," says one to the other as he handles the object, "such fine English workmanship." There was no irony, though it seemed hardly credible that British engineering could have been prized in Germany only 40 years before, given that at that Thatcher moment the typical British workshop was being sold abroad as scrap.

Germany's technical superiority was plain to see by the 1960s, but my own enlightenment came rather earlier, when I was eight or nine and the recipient of German gifts at Christmas. These came from two sources. In 1945, my family had befriended a prisoner-of-war and stayed in touch with him when he went home to Hamburg. We sent parcels of coffee beans, while a small box of marzipan or a bottle of eau-de-cologne came in the other direction. But as the years passed, the German presents grew more sophisticated. For me, a toy fire engine with a working water pump; for my parents, topographical books of black and white photographs printed on cream paper that felt like velvet. Perhaps these luxuries could also be found in Britain, but we had never seen them.

These were portents. The epiphany – not that I thought of it like that at the time – arrived when my older brother came home on leave from national service in Germany. He was the second source of gifts, and once, from his kitbag, produced two model railway coaches, gauge 00 to match my Hornby set but made by the German toymakers, Marklin. Their detail was superb. My tinplate Hornby carriages relied on painting to produce an effect of windows and door handles, but on their Marklin equivalents the windows really were transparent and the pattern of rivets below them stood out in relief. The war hadn't been over 10 years, and somehow Germany was making things as inconsequential as model trains that were more convincing than our own. Suddenly "Made in England" no longer suggested a singularly high quality, not that in 1954 it was easy in Britain to find goods made anywhere else.

Fear and envy of German manufacturing prowess began a long time before, as any economic history will tell you. Together with the US, Germany began to displace Britain as the world's foremost industrial nation well before the close of the 19th century. Books and newspaper articles sounded the alarm ("American furniture in England – a further indictment of the trade unions," read a Daily Mail headline in 1900), but did little to prevent Britain falling further behind in the new industries that became so important in the 20th century. Germany established a clear lead in chemicals, electrical engineering, optics and instrument-making. At the outbreak of war in 1914, the British government found that every magnet in the country came from Stuttgart, while German chemical works supplied all the khaki dye for British military uniforms.

To a large extent, British decline was inevitable: other nations had learned how to make things and export markets would naturally shrink. But the particular contrast with Germany was instructive when it came to scientific education and the social position of manufacturers and engineers. According to Peter Mathias's classic economic history, The First Industrial Nation, only a dozen students were reading for a degree in natural sciences at Cambridge in 1872. Germany, meanwhile, had 11 entire universities devoted to science and technology. Its educational system embraced the idea of manufacturing, while England's public schools and ancient universities held it at arm's length.

Finance became the acceptable business profession for gentlemen. In the words of another historian, Martin Wiener, finance "involved the extraction of wealth by associating with people of one's own class in fashionable surroundings, not by dealing with … the working and lower-middle classes". In this way, the City became part of the elite and "could call upon government much more effectively than could industry to favour and support its interests".

This is a familiar and by now hardly controversial diagnosis of the British malaise, and every so often a government or a politician promises a fundamental reform in political attitudes, praising the country's long tradition of scientific discovery and technical invention. A few television programmes endorse the same point; Sir James Dyson appears with his vacuum cleaner. But, beyond that, nothing much happens. Look around the frontbenches on both sides of the Commons. Who there dares upset the City? Who there ever made anything three-dimensional, or even had a parent who did? Which of them would risk the chamber pot of failed hopes being emptied over their heads by calling for a national industrial strategy?

It would be lovely to emulate the industrial success of the Germans, but so much history is very hard to undo. The one cheerful note (or perhaps more a vengeful one) is that Marklin, which made my memorable little carriages, is now owned by a private equity company based in London.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)