'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Tuesday, 22 August 2023

Saturday, 17 June 2023

Economics Essay 44: Economic Recovery from Shocks

Discuss the extent to which economies are likely to recover quickly from negative demand side shocks in reality.

The speed and extent of economic recovery from negative demand-side shocks in reality can vary depending on the following factors:

Magnitude and Duration of the Shock: The severity and duration of the negative demand-side shock can significantly impact the recovery. For instance, the global financial crisis that started in 2008 originated in the United States with the collapse of the subprime mortgage market. The magnitude of the shock and its ripple effects led to a prolonged and challenging recovery for many economies worldwide. Countries heavily reliant on exports and with large financial sectors, such as Ireland and Spain, faced protracted recessions and slow recoveries. In contrast, economies with strong policy responses, like Germany, recovered relatively quickly due to their diversified industrial base and robust fiscal stimulus measures.

Economic Structure and Diversity: The structure and diversity of an economy can influence its ability to recover from a demand-side shock. For example, the Eurozone debt crisis affected countries such as Greece, Portugal, and Spain. These economies faced high levels of debt, banking sector weaknesses, and structural rigidities, which hindered their recovery. The need for austerity measures and structural reforms to address underlying imbalances slowed down their recovery processes, resulting in extended periods of economic contraction and high unemployment rates. In contrast, countries with more diversified economies and robust policy responses, such as Germany, demonstrated a faster recovery.

International Factors: Economic recovery can be influenced by global factors such as trade relationships, exchange rates, and international financial conditions. The Asian financial crisis in 1997 provides an example of the varying speed of recovery following a negative demand shock. South Korea implemented timely and comprehensive policy responses, including structural reforms, bank recapitalization, and international financial assistance. As a result, it experienced a relatively quick recovery. In contrast, countries like Indonesia faced more significant challenges due to political instability and delayed policy actions, leading to a more protracted recovery period.

Policy Response: The effectiveness and timeliness of policy responses play a crucial role in shaping the speed of recovery. The COVID-19 pandemic serves as a recent example of a negative demand-side shock. Economies like New Zealand and South Korea demonstrated quicker recoveries due to their ability to control the virus and restore consumer confidence through targeted fiscal measures and support for affected sectors. In contrast, countries heavily dependent on tourism, such as Thailand and Spain, faced significant challenges due to the sharp decline in international travel.

These examples highlight the diverse outcomes and factors that influence the speed and extent of recovery from negative demand-side shocks. The severity of the shock, policy responses, structural factors, and external conditions all play crucial roles in shaping the recovery trajectory of economies.

Saturday, 26 June 2021

Sunday, 20 June 2021

Friday, 23 February 2018

Zombie companies walk among us

For vampires, the weakness is garlic. For werewolves, it’s a silver bullet. And for zombies? Perhaps a rise in interest rates will do the trick.

Friday, 22 January 2016

Don’t blame China for these global economic jitters

Ha Joon Chang in The Guardian

The US stock market has just had the worst start to a year in its history. At the same time, European and Japanese stock markets have lost around 10% and 15% of their values respectively; the Chinese stock market has resumed its headlong dash downward; and the oil price has fallen to the lowest level in 12 years, reflecting (and anticipating) worldwide economic slowdown.

According to the dominant economic narrative of recent times, 2016 was the year when the world economy would recover fully from the 2008 crash. The US would lead this recovery by generating growth and jobs via fiscal conservatism and pro-business policies. Reflecting the economy’s robust growth, the US stock market reached new heights in 2015, although disrupted by the mess in the Chinese stock market over the summer. By last October, US unemployment had fallen from the post-crisis peak of 10% to 5%, bringing it back close to the pre-crisis low. In a show of confidence, last month the US Federal Reserve finally raised its interest rate for the first time in nine years.

Not far behind the US, the story goes, have been Britain and Ireland. Hit harder than the US by the financial crisis, they have, however, recovered handsomely because they kept their nerve and stuck to the right, if unpopular, policies. Spending cuts, focused on wasteful welfare spending, accelerated job creation by making it more difficult for people to live off the taxpayer. They sensibly didn’t give in to the banker-bashers and chose not to over-regulate the financial sector.

Even the continental European economies have been finally picking up, it was said, having accepted the need for fiscal discipline, labour market reform and cutting business regulations. The world – at least the rich world – was finally set for a full recovery. So what has gone wrong?

Those who put forward the narrative are now trying to blame China in advance for the coming economic woes. George Osborne has been at the forefront, warning this month of a “dangerous cocktail of new threats” in which the devaluation of the Chinese currency and the fall in oil prices (both in large part due to China’s economic slowdown) figured most prominently. If our recovery was to be blown off course, he implied, it would be because China had mismanaged its economy.

China is, of course, an important factor in the global economy. Only 2.5% of the world economy in 1978, on the eve of its economic reform, it now accounts for around 13%. However, its importance should not be exaggerated. As of 2014, the US (22.5%) the eurozone (17%) and Japan (7%) together accounted for nearly half of the world economy. The rich world vastly overshadows China. Unless you are a developing economy whose export basket is mainly made up of primary commodities destined for China, you cannot blame your economic ills on its slowdown.

The truth is that there has never been a real recovery from the 2008 crisis in North America and western Europe. According to the IMF, at the end of 2015, inflation-adjusted income per head (in national currency) was lower than the pre-crisis peak in 11 out of 20 of those countries. In five (Austria, Iceland, Ireland, Switzerland and the UK), it was only just higher – by between 0.05% (Austria) and 0.3% (Ireland). Only in four countries – Germany, Canada, the US and Sweden – was per-capita income materially higher than the pre-crisis peak.

Even in Germany, the best performing of those four countries, per capita income growth rate was just 0.8% a year between its last peak (2008) and 2015. The US growth rate, at 0.4% per year, was half that. Compare that with the 1% annual growth rate that Japan notched up during its so-called “lost two decades” between 1990 and 2010.

To make things worse, much of the recovery has been driven by asset market bubbles, blown up by the injection of cash into the financial market through quantitative easing. These asset bubbles have been most dramatic in the US and UK. They were already at an unprecedented level in 2013 and 2014, but scaled new heights in 2015. The US stock market reached the highest ever level in May 2015 and, after the dip over the summer, more or less came back to that level in December. Having come down by nearly a quarter from its April 2015 peak, Britain’s stock market is currently not quite so inflated, but the UK has another bubble to reckon with, in the housing market, where prices are 7% higher than the pre-crisis peak of 2007.

Thus seen, the main causes of the current economic turmoil lie firmly in the rich nations – especially in the finance-driven US and UK. Having refused to fundamentally restructure their economies after 2008, the only way they could generate any sort of recovery was with another set of asset bubbles. Their governments and financial sectors talked up anaemic recovery as an impressive comeback, propagating the myth that huge bubbles are a measure of economic health.

Whether or not the recent market turmoil leads to a protracted slide or a violent crash, it is proof that we have wasted the past seven years propping up a bankrupt economic model. Before things get any worse, we need to replace it with one in which the financial sector is made less complex and more patient, investment in the real economy is encouraged by fiscal and technological incentives, and measures are brought in to reduce inequality so that demand can be maintained without creating more debts.

None of these will be easy to implement, but we know what the alternative is – a permanent state of low growth, instability, and depressed living standards for the vast majority.

Thursday, 12 February 2015

Germany faces impossible choice as Greek, Spanish and Italian austerity revolt spreads

Monday, 24 February 2014

This is no recovery, this is a bubble – and it will burst

Sunday, 1 December 2013

Is Britain's economy really on the path to prosperity?

- Heather Stewart, economics editor

- The Observer,

Sunday, 6 October 2013

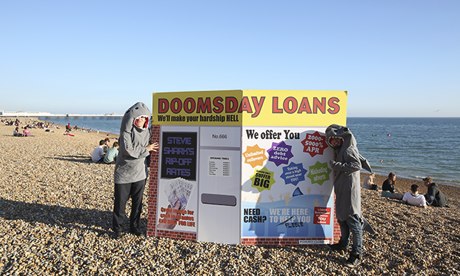

What kind of a recovery is this when so many people are crippled by debt?

Saturday, 17 August 2013

Osborne economics is not an invincible force of nature