Financial despair, often fuelled by payday lending, poisons the present and undermines hope and opportunity

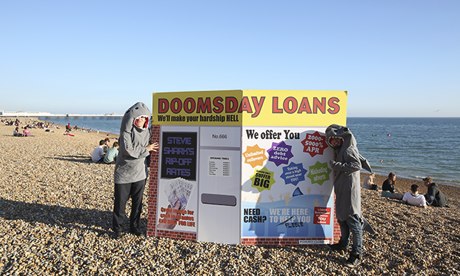

Anti-payday loans campaigners at Brighton for the Labour conference. Photograph: David Levene for the Observer

Britain is once again being talked about as a place of prosperity. We are told to be relieved that the worst of the financial crisis has passed; the nation is becoming, according to David Cameron, a land of opportunity. Yet the same government that talks tough on national debt turns a blind eye to the personal debt the public have racked up on their watch. So while confidence may return to Britain's elite, millions of others endure sleepless nights about their future.

These are the people drowning in debts built up coping with the consequences of a recession in which wages froze but prices continued to rise. With little help from the government or banks, payday lending filled the gap. That leaves many people trapped, balancing multiple loans with multiple companies. They are trying to put food on their tables and heat their homes while paying off high-cost debts. One constituent was juggling eight different payday loans, to try and cover lost hours at work. She eventually lost her flat and only cleared her debt with her redundancy payoff; she is now back in rental property.

Last week, a Sure Start in Walthamstow, north-east London, told me of 30 clients served with eviction notices the day the benefit cap was introduced. Parents not even given a chance by landlords now face an overcrowded private rental sector that shuns housing benefit claimants. Several have been referred to social services as fears about debt and homelessness create unbearable stress.

Benefit cuts are the tip of the iceberg of pressures pushing the public into the red. As working hours have been slashed, so a wave of part-time jobs has led to underemployment and wasted productivity. Rail and energy prices have rocketed without competition from government to drive down the costs of getting to work or keeping warm. Asking those with thousands in unsecured personal debt – our current national average is £8,000 and growing – to take on risks and responsibilities is a non-starter. What hope saving for old age or social care costs, sending children to university or a housing deposit when the end of the month, let alone the end of the year, appears so distant for so many?

Which is why the toxicity of payday lending doesn't just feed today's cost of living crisis, but affects tomorrow's country of opportunity too. Cameron talks about prospects, but by his inaction we know his vision is one for the privileged few.

The failure of Project Merlin to lend to businesses shows coalition incompetence; the failure to provide affordable credit to our communities in such circumstances is inexcusable. Little wonder payday lenders now make £1m each week bleeding cash from consumers desperate to bridge the gap between a rocky jobs market and rising everyday expenses.

Such borrowing only compounds budgeting problems. Debt charity StepChange report 22% of payday loan clients have council tax arrears compared with 13% of all other clients, and 14% of them are behind on rent compared to 9% of all other clients. Such difficulties are music to the ears of companies for whom the more in debt a customer is the more profit they make.

Not every customer gets into financial difficulty, but enough find the price they pay for credit means they have to borrow again; 50% of profits in this industry come from refinancing, with those who take loans out repeatedly creating the largest return. One company makes 23% of its total profit from just 34,000 people who borrow every month, not able to cover their outgoings without such expensive finance. In turn, such loans devastate credit ratings, leaving users few other options to make ends meet.

Plans from the Financial Conduct Authority to limit rolling over of loans and lender access to bank accounts offer some progress. Yet until we deal with the cost of credit itself, there is little prospect of real change or protection for British consumers. Capping the total cost of credit, as they have in Japan and Canada, sets a ceiling on the amount charged, including interest rates, admin fees and late repayments. This allows borrowers to have certainty about debts they incur and firms have little incentive to keep pushing loans as they hit a limit on what they can squeeze out of a customer.

Lenders aggressively campaign against such measures knowing their profits, not customers, would take a hit. They threaten that caps would drive them out of business and push borrowers to illegal lenders – when evidence from other countries shows the reverse is true. Labour's commitment to capping in the face of such industry and government opposition reflects not just different priorities but different perspectives about in whose interests to act.

Only this government would make a virtue of defending companies that most now agree are out of control. The Office of Fair Trading is so concerned it has referred the entire industry to the Competition Commission. Its report into payday lending details how consumers are repeatedly sold loans they cannot hope to clear. The Citizens Advice Bureau found 76% of payday loan customers would have a misconduct case to take to the Financial Ombudsman. Despite overwhelming evidence of the toxic nature of their business model, these companies are being allowed to continue trading as if the consumer detriment it causes is a matter for the borrower to navigate rather than of public interest to address. Wanting to get regulation right should not prevent us from acting to avoid what, if left unchecked, will no doubt become the next mis-selling debacle akin to PPI.

In its willingness to front out concern about the fate of its 5 million customers, the danger is that this industry – and this government – wins the argument. They portray financial regulation as anti-competitive, anti-personal responsibility and anti-British, conveniently overlooking the market failure their behaviour represents.

This fosters a pessimism that the best we can do is pick up the pieces of the lives ruined, homes lost and credit ratings destroyed by companies exploiting the desperation of a country living on tick. Supporting alternative credit is vital, but so, too, is securing an alternative credit market and collective consumer action.

The longer we wait to learn the lessons of other countries on the use of caps, real-time credit checking and credit unions, the more people these legal loan sharks will snare into a cycle of inescapable debt – and a future where that land of opportunity is all too far away.

Stella Creasy is Labour MP for Walthamstow

No comments:

Post a Comment