'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label captain. Show all posts

Showing posts with label captain. Show all posts

Thursday, 20 January 2022

Sunday, 21 January 2018

Kohli's arrogance helps his game but not the team

Ramachandra Guha in Cricinfo

Watching Virat Kohli play two exquisite square drives against Australia in March 2016, I tweeted: "There goes my boyhood hero G. R. Viswanath from my all time India XI." Those boundaries formed part of a match-winning innings of 82 in a T20 World Cup quarter-final, and they confirmed for me Kohli's cricketing greatness.

I had first been struck by how good he was when watching, at the ground, a hundred he scored in a Test in Bangalore in 2012. Against a fine New Zealand attack, Sachin Tendulkar looked utterly ordinary, whereas the man who, the previous year, had carried Tendulkar on his shoulders in tribute was totally in command. Two years later, I saw on the telly every run of his dazzling 141 in Adelaide, when, in his first Test as captain, Kohli almost carried India to a remarkable win.

The admiration had steadily accumulated. So, as he struck the miserly James Faulkner and Nathan Coulter-Nile for those two defining boundaries in that T20 match in 2016, the sentimental attachments of childhood were decisively vanquished by sporting prowess. Virender Sehwag and Sunil Gavaskar would open the batting in my fantasy XI; Rahul Dravid and Tendulkar would come next; and Kohli alone could be No. 5.

That was two years ago. Now, after the staggering series of innings he has played since - not least that magnificent 153 in India's most recent Test - I would go even further. In all formats and in all situations, Kohli might already be India's greatest ever batsman.

Their orthodoxy and classicism, which served Dravid and Gavaskar so well in the Test arena, constrained them in limited-overs cricket. Sehwag had a spectacular Test record, but his one-day career was, by his own exalted standards, rather ordinary. Tendulkar was superb, often supreme, in the first innings of a Test, but he was not entirely to be relied upon in the fourth innings, or even when batting second in the 50-overs game. Besides, being captain made Tendulkar nervous and insecure in his strokeplay. On the other hand, captaincy only reinforces Kohli's innate confidence, and of course, he is absolutely brilliant while chasing.

"No one in the entire history of the game in India has quite had Kohli's combination of cricketing greatness, personal charisma, and this extraordinary drive and ambition to win for himself and his team"

I have met Kohli only once, and am unlikely to ever meet him again. But from our single conversation, and from what I have seen of him otherwise, I would say that of all of India's great sportsmen past and present, he is the most charismatic. He is a man of a manifest intelligence (not merely cricketing) and of absolute self-assurance. Gavaskar and Dravid were as articulate as Kohli in speech, but without his charisma. Kapil and Dhoni had equally strong personalities but lacked Kohli's command of words.

I was witness to the reach and range of Kohli's dominating self in my four months in the BCCI's Committee of Administrators. The board's officials worshipped him even more than the Indian cabinet worships Narendra Modi. They deferred to him absolutely, even in matters like the Future Tours Programme or the management of the National Cricket Academy, which were not within the Indian captain's ken.

In any field in India - whether it be politics or business or academia or sport - when strength of character is combined with solidity of achievement, it leads to an individual's dominance over the institution. And the fact is that, on and off the field, Kohli is truly impressive. No one in the entire history of the game in our country has quite had his combination of cricketing greatness, personal charisma, and this extraordinary drive and ambition to win for himself and his team. The only person who came close, even remotely close, is (or was) Anil Kumble.

Kumble was, by some distance, the greatest bowler produced by India. He was a superb thinker on the game. Moreover, he was well educated, well read, and had an interest in society and politics. And he was not lacking in an awareness of his own importance, although he carried his self-belief in a Kannadiga rather than Punjabi fashion.

It may be that Kumble alone is in the Kohli league as a cricketer and character. That perhaps is why they clashed and perhaps why Kumble had to go.

But why was he replaced by someone so strikingly inferior, in character and cricketing achievement, to the team's captain? A person with no coaching experience besides? Only because, like the BCCI, the chairman of the Supreme Court-appointed Committee of Administrators surrendered his liberties and his independence when confronted by the force of Kohli's personality. As did the so-called Cricket Selection Committee. Ravi Shastri was chosen over Tom Moody (and other contenders) because Vinod Rai, Tendulkar, Sourav Gangulyand VVS Laxman were intimidated by the Indian captain into subordinating the institution to the individual. The unwisdom of that decision was masked when India played at home, against weak opposition, but it can no longer be concealed.![]()

Had the BCCI thought more about cricket than commerce, we would not have had to go into this series against South Africa without a single practice match. Had the selectors been wiser or braver, India might not have been 2-0 down now.

Some Kohli bhakts will complain at the timing of this article, written after the Indian captain played such a stupendous innings himself. But this precisely is the time to remind ourselves of how we must not allow individual greatness to shade into institutional hubris. Kohli did all he could to keep India in the game, but the power of an individual in a team game can go only so far. Had Ajinkya Rahane played both Tests, had Bhuvneshwar Kumar played this Test, had India gone two weeks earlier to South Africa instead of playing gully cricket at home with the Sri Lankans, the result might have been quite different.

The BCCI and their cheerleaders brag about India being the centre of world cricket. This may be true in monetary terms, but decidedly not in sporting terms. From my own stint in the BCCI, I reached this melancholy conclusion: that were the game better administered in India, the Indian team would never lose a series. There are ten times as many cricket-crazy Indians as there are football-mad Brazilians. The BCCI has huge cash reserves. With this demographic and financial base, India should always and perennially have been the top team in all formats of the game. If India still lost matches and series, if India still hadn't, in 70 years of trying, won a Test series in Australia (a country with about as many people as Greater Mumbai), then surely the fault lay with how the game was mismanaged in the country.

To the corruption and cronyism that has so long bedevilled Indian cricket has recently been added a third ailment: the superstar syndrome. Kohli is a great player, a great leader, but in the absence of institutional checks and balances, his team will never achieve the greatness he and his fans desire.

When, in the 1970s, India won their first Test series in the West Indies and in England, Vijay Merchant was chairman of selectors. When much later, India began winning series regularly at home, the likes of Gundappa Viswanath and Dilip Vengsarkar were chairmen of selectors. Their cricketing achievements were as substantial as that of the existing players. They had the sense to consult the captain on team selection, but also had the stature to assert their own preferences over his when required. On the other hand, the present set of selectors have all played a handful of Tests apiece. The coach, Shastri, played more, but he was never a true great, and his deference to the captain is in any case obvious.

In Indian cricket today, the selectors, coaching staff and administrators are all pygmies before Kohli. That must change. The selectors must be cricketers of real achievement (as they once were). If not great cricketers themselves, they must at least have the desire and authority to stand up to the captain. Likewise, the coach must have the wisdom and courage to, when necessary, assert his authority over Kohli's (as when Kumble picked Kuldeep Yadav, a move that decided a Test and series in India's favour). And the administrators must schedule the calendar to maximise India's chances of doing well overseas, rather than with an eye to their egos and purses. (The decision not to have an extended tour of South Africa was partly influenced by the BCCI's animosity towards Cricket South Africa.)

Only when India consistently win Tests and series in South Africa, and only when they do likewise in Australia, can they properly consider themselves world champions in cricket. They have the team, and the leader, to do it. However, the captain's authority and arrogance, so vital and important to his personal success, must be moderated and managed if it is to translate into institutional greatness.

Kohli is still only 29. He will surely lead India in South Africa again and he has more than one tour of Australia ahead of him. Two years ago he secured a firm place in my all-time India XI. My wish, hope and desire is for Kohli to end his career with him also being the captain of my XI.

Watching Virat Kohli play two exquisite square drives against Australia in March 2016, I tweeted: "There goes my boyhood hero G. R. Viswanath from my all time India XI." Those boundaries formed part of a match-winning innings of 82 in a T20 World Cup quarter-final, and they confirmed for me Kohli's cricketing greatness.

I had first been struck by how good he was when watching, at the ground, a hundred he scored in a Test in Bangalore in 2012. Against a fine New Zealand attack, Sachin Tendulkar looked utterly ordinary, whereas the man who, the previous year, had carried Tendulkar on his shoulders in tribute was totally in command. Two years later, I saw on the telly every run of his dazzling 141 in Adelaide, when, in his first Test as captain, Kohli almost carried India to a remarkable win.

The admiration had steadily accumulated. So, as he struck the miserly James Faulkner and Nathan Coulter-Nile for those two defining boundaries in that T20 match in 2016, the sentimental attachments of childhood were decisively vanquished by sporting prowess. Virender Sehwag and Sunil Gavaskar would open the batting in my fantasy XI; Rahul Dravid and Tendulkar would come next; and Kohli alone could be No. 5.

That was two years ago. Now, after the staggering series of innings he has played since - not least that magnificent 153 in India's most recent Test - I would go even further. In all formats and in all situations, Kohli might already be India's greatest ever batsman.

Their orthodoxy and classicism, which served Dravid and Gavaskar so well in the Test arena, constrained them in limited-overs cricket. Sehwag had a spectacular Test record, but his one-day career was, by his own exalted standards, rather ordinary. Tendulkar was superb, often supreme, in the first innings of a Test, but he was not entirely to be relied upon in the fourth innings, or even when batting second in the 50-overs game. Besides, being captain made Tendulkar nervous and insecure in his strokeplay. On the other hand, captaincy only reinforces Kohli's innate confidence, and of course, he is absolutely brilliant while chasing.

"No one in the entire history of the game in India has quite had Kohli's combination of cricketing greatness, personal charisma, and this extraordinary drive and ambition to win for himself and his team"

I have met Kohli only once, and am unlikely to ever meet him again. But from our single conversation, and from what I have seen of him otherwise, I would say that of all of India's great sportsmen past and present, he is the most charismatic. He is a man of a manifest intelligence (not merely cricketing) and of absolute self-assurance. Gavaskar and Dravid were as articulate as Kohli in speech, but without his charisma. Kapil and Dhoni had equally strong personalities but lacked Kohli's command of words.

I was witness to the reach and range of Kohli's dominating self in my four months in the BCCI's Committee of Administrators. The board's officials worshipped him even more than the Indian cabinet worships Narendra Modi. They deferred to him absolutely, even in matters like the Future Tours Programme or the management of the National Cricket Academy, which were not within the Indian captain's ken.

In any field in India - whether it be politics or business or academia or sport - when strength of character is combined with solidity of achievement, it leads to an individual's dominance over the institution. And the fact is that, on and off the field, Kohli is truly impressive. No one in the entire history of the game in our country has quite had his combination of cricketing greatness, personal charisma, and this extraordinary drive and ambition to win for himself and his team. The only person who came close, even remotely close, is (or was) Anil Kumble.

Kumble was, by some distance, the greatest bowler produced by India. He was a superb thinker on the game. Moreover, he was well educated, well read, and had an interest in society and politics. And he was not lacking in an awareness of his own importance, although he carried his self-belief in a Kannadiga rather than Punjabi fashion.

It may be that Kumble alone is in the Kohli league as a cricketer and character. That perhaps is why they clashed and perhaps why Kumble had to go.

But why was he replaced by someone so strikingly inferior, in character and cricketing achievement, to the team's captain? A person with no coaching experience besides? Only because, like the BCCI, the chairman of the Supreme Court-appointed Committee of Administrators surrendered his liberties and his independence when confronted by the force of Kohli's personality. As did the so-called Cricket Selection Committee. Ravi Shastri was chosen over Tom Moody (and other contenders) because Vinod Rai, Tendulkar, Sourav Gangulyand VVS Laxman were intimidated by the Indian captain into subordinating the institution to the individual. The unwisdom of that decision was masked when India played at home, against weak opposition, but it can no longer be concealed.

Had the BCCI thought more about cricket than commerce, we would not have had to go into this series against South Africa without a single practice match. Had the selectors been wiser or braver, India might not have been 2-0 down now.

Some Kohli bhakts will complain at the timing of this article, written after the Indian captain played such a stupendous innings himself. But this precisely is the time to remind ourselves of how we must not allow individual greatness to shade into institutional hubris. Kohli did all he could to keep India in the game, but the power of an individual in a team game can go only so far. Had Ajinkya Rahane played both Tests, had Bhuvneshwar Kumar played this Test, had India gone two weeks earlier to South Africa instead of playing gully cricket at home with the Sri Lankans, the result might have been quite different.

The BCCI and their cheerleaders brag about India being the centre of world cricket. This may be true in monetary terms, but decidedly not in sporting terms. From my own stint in the BCCI, I reached this melancholy conclusion: that were the game better administered in India, the Indian team would never lose a series. There are ten times as many cricket-crazy Indians as there are football-mad Brazilians. The BCCI has huge cash reserves. With this demographic and financial base, India should always and perennially have been the top team in all formats of the game. If India still lost matches and series, if India still hadn't, in 70 years of trying, won a Test series in Australia (a country with about as many people as Greater Mumbai), then surely the fault lay with how the game was mismanaged in the country.

To the corruption and cronyism that has so long bedevilled Indian cricket has recently been added a third ailment: the superstar syndrome. Kohli is a great player, a great leader, but in the absence of institutional checks and balances, his team will never achieve the greatness he and his fans desire.

When, in the 1970s, India won their first Test series in the West Indies and in England, Vijay Merchant was chairman of selectors. When much later, India began winning series regularly at home, the likes of Gundappa Viswanath and Dilip Vengsarkar were chairmen of selectors. Their cricketing achievements were as substantial as that of the existing players. They had the sense to consult the captain on team selection, but also had the stature to assert their own preferences over his when required. On the other hand, the present set of selectors have all played a handful of Tests apiece. The coach, Shastri, played more, but he was never a true great, and his deference to the captain is in any case obvious.

In Indian cricket today, the selectors, coaching staff and administrators are all pygmies before Kohli. That must change. The selectors must be cricketers of real achievement (as they once were). If not great cricketers themselves, they must at least have the desire and authority to stand up to the captain. Likewise, the coach must have the wisdom and courage to, when necessary, assert his authority over Kohli's (as when Kumble picked Kuldeep Yadav, a move that decided a Test and series in India's favour). And the administrators must schedule the calendar to maximise India's chances of doing well overseas, rather than with an eye to their egos and purses. (The decision not to have an extended tour of South Africa was partly influenced by the BCCI's animosity towards Cricket South Africa.)

Only when India consistently win Tests and series in South Africa, and only when they do likewise in Australia, can they properly consider themselves world champions in cricket. They have the team, and the leader, to do it. However, the captain's authority and arrogance, so vital and important to his personal success, must be moderated and managed if it is to translate into institutional greatness.

Kohli is still only 29. He will surely lead India in South Africa again and he has more than one tour of Australia ahead of him. Two years ago he secured a firm place in my all-time India XI. My wish, hope and desire is for Kohli to end his career with him also being the captain of my XI.

Sunday, 25 June 2017

What the Kohli-Kumble saga tells us

Ian Chappell in Cricinfo

Pakistan soundly beat India in the Champions Trophy final, and it has been interesting, to say the least, to witness the aftermath.

Firstly, the Indian coach, Anil Kumble, resigned. Then the Pakistan players - not surprisingly - were welcomed home as heroes. This was followed by an ICC announcement that Afghanistan and Ireland have been added to the list of Test-playing nations, increasing the number to 12.

Kumble's resignation was no great surprise, as he's a strong-minded individual and the deteriorating relationship between him and the captain, Virat Kohli, had reached the stage of being a distraction. Kumble's character is relevant to any discussion about India's future coaching appointments. The captain is the only person who can run an international cricket team properly, because so much of the job involves on-field decision making. Also, a good part of the leadership role - performed off the field - has to be handled by the captain, as it helps him earn the players' respect, which is crucial to his success.

Consequently a captain has to be a strong-minded individual and decisive in his thought process. To put someone of a similar mindset in a position where he's advising the captain is inviting confrontation.

The captain's best advisors are his vice-captain, a clear-thinking wicketkeeper, and one or two senior players. They are out on the field and can best judge the mood of the game and what advice should be offered to the captain and when.

The best off-field assistance for a captain will come from a good managerial type. Someone who can attend to duties that are not necessarily related to winning or losing cricket matches, but done efficiently, can contribute to the success of the team.

The last thing a captain needs is to come off the field and have someone second-guess his decisions. He also doesn't need a strong-minded individual (outside his advisory group) getting too involved in the pre-match tactical planning. Too often I see captaincy that appears to be the result of the previous evening's planning, and despite ample evidence that it's hindering the team's chances of victory, it remains the plan throughout the day.

This is generally a sure sign that the captain is following someone else's plan and that he, the captain, is the wrong man for the job.

India is fortunate to have two capable leaders in Kohli and the man who stood in for him during the Test series with Australia, Ajinkya Rahane.

It's Kohli's job as captain to concentrate on things that help win or lose cricket matches, and his off-field assistants' task is to ensure he is not distracted in trying to achieve victory.

India's opponents in the final, Pakistan, were unusually free of any controversies during the tournament. They were capably led by Sarfraz Ahmed, who appeared to become more and more his own man as the tournament progressed.

Pakistan soundly beat India in the Champions Trophy final, and it has been interesting, to say the least, to witness the aftermath.

Firstly, the Indian coach, Anil Kumble, resigned. Then the Pakistan players - not surprisingly - were welcomed home as heroes. This was followed by an ICC announcement that Afghanistan and Ireland have been added to the list of Test-playing nations, increasing the number to 12.

Kumble's resignation was no great surprise, as he's a strong-minded individual and the deteriorating relationship between him and the captain, Virat Kohli, had reached the stage of being a distraction. Kumble's character is relevant to any discussion about India's future coaching appointments. The captain is the only person who can run an international cricket team properly, because so much of the job involves on-field decision making. Also, a good part of the leadership role - performed off the field - has to be handled by the captain, as it helps him earn the players' respect, which is crucial to his success.

Consequently a captain has to be a strong-minded individual and decisive in his thought process. To put someone of a similar mindset in a position where he's advising the captain is inviting confrontation.

The captain's best advisors are his vice-captain, a clear-thinking wicketkeeper, and one or two senior players. They are out on the field and can best judge the mood of the game and what advice should be offered to the captain and when.

The best off-field assistance for a captain will come from a good managerial type. Someone who can attend to duties that are not necessarily related to winning or losing cricket matches, but done efficiently, can contribute to the success of the team.

The last thing a captain needs is to come off the field and have someone second-guess his decisions. He also doesn't need a strong-minded individual (outside his advisory group) getting too involved in the pre-match tactical planning. Too often I see captaincy that appears to be the result of the previous evening's planning, and despite ample evidence that it's hindering the team's chances of victory, it remains the plan throughout the day.

This is generally a sure sign that the captain is following someone else's plan and that he, the captain, is the wrong man for the job.

India is fortunate to have two capable leaders in Kohli and the man who stood in for him during the Test series with Australia, Ajinkya Rahane.

It's Kohli's job as captain to concentrate on things that help win or lose cricket matches, and his off-field assistants' task is to ensure he is not distracted in trying to achieve victory.

India's opponents in the final, Pakistan, were unusually free of any controversies during the tournament. They were capably led by Sarfraz Ahmed, who appeared to become more and more his own man as the tournament progressed.

Thursday, 13 April 2017

Why are most captains inevitably batsmen?

Rob Steen in Cricinfo

James Anderson: one of many who have questioned why more fast bowlers aren't considered for captaincy © Getty Images

James Anderson: one of many who have questioned why more fast bowlers aren't considered for captaincy © Getty Images

James Anderson has nothing to prove to anyone but, one assumes, himself. Nor is he one to mince words. So when he expresses disappointment at not having been considered for the England Test captaincy, then says he doesn't know why more fast bowlers aren't entrusted with leadership, and leaves the question hanging in the air, the point is worth considering. What possible reason can there be to maintain the lazy, prejudiced, time-dishonoured view that batsmen should be the default choice as coin-tossers?

Naturally, the record books tell their own flagrantly biased story: of the 57 men to have captained in 25 or more Tests, 46 have been batsmen first and foremost (including 15 of the 16 who have done so on 50-plus occasions, the exception being MS Dhoni). Even if we include two top-notch allrounders, Imran Khan and Garry Sobers, the number of seam bowlers runs to just six: Imran (48 Tests), Sobers (39), Kapil Dev (34), Darren Sammy (30), Shaun Pollock (26) and Wasim Akram (25). Still, that's twice as many representatives in the chart as the spin fraternity can muster - Daniel Vettori (32), Ray Illingworth (31) and Richie Benaud (28) - never mind the stumpers, who contribute only Dhoni (60) and Mushfiqur Rahim (30). As for those who would classify him as a spinner, Sobers is remembered better by this column for his left-arm swing than his spin, so let's indulge it.

It gets worse. Late last year the Cricketer magazine asked readers to vote for their favourite England captain; of the 23 candidates proffered, only Illingworth did not count run-making as his primary occupation. It's all a matter of class, of course. Back when such distinctions were made, the amateurs were almost invariably batsmen, cravat-wearing types accustomed to being served hittable offerings by lowly, gnarly professionals; chaps to whom authority was a birthright. "In England," noted Mike Brearley in his definitive The Art of Captaincy, a revised edition of which is due out this summer, "charisma and leadership have traditionally been associated with the upper class; with that social strata that gives its members what Kingsley Amis called 'the voice accustomed to command'."

If Anderson is "all for bowlers being captains", Don Bradman offered the counter-argument in The Art of Cricket, reasoning that they would lack objectivity about their own workload. "They tend either to over-bowl themselves or not to bowl enough," reinforced Brearley, "from conceit, modesty or indeed self-protection." On the other hand, he continued, two of the best postwar captains in his view were Benaud and Illingworth, outliers both.

It's all a matter of class, of course. Back when such distinctions were made, the amateurs were almost invariably batsmen, cravat-wearing types accustomed to being served hittable offerings by lowly, gnarly professionals

In his 1980 book Captaincy, Illingworth argued that the allrounder, and especially those who were also twirlers like himself and Benaud, were the best equipped for the job. He also took issue with Bradman in his autobiography Yorkshire and Back:

"Basically, I felt my two strongest points were, first, after playing for quite a time I knew batsmen pretty well and I knew their temperaments so I thought I set good fields; and second, I think I was able to get the best out of people because they trusted me. I knew when to attack and when to defend, which governed field placing, and my handling of the bowling."

Video has aided such knowledge, granted, but there's no substitute for a bowler's instinct.

Benaud also rated Illingworth high above the herd. In his 1984 book, Benaud of Reflection he wrote:

"He was a deep thinker on the game, without having any of the theories which sometimes produce woolly thinking from captains. He was a shrewd psychologist and one who left his team in no doubt as to what he required of them. Above all, though, he made his decisions before the critical moment. It was never a case of thinking for an over or two about whether or not a move should be made. If he had a hunch it would work, and if it seemed remotely within the carefully laid-down plans of the series, then he would do it."

What counted above all, felt Illingworth, under whose charge England enjoyed most of their record 26-match unbeaten run between 1969 and 1971, was honesty. During the summer of 1970, opener Brian Luckhurst asked him, somewhat tentatively, whether he had any chance of being picked for that winter's Ashes tour, having made a fair few runs in the first three Tests of the series against a powerful Rest of the World attack. "You're almost on the boat now," replied Illy. "Now what I liked about that," he recollected, "was that Brian had only played three matches with me, and yet he felt that not only could he ask a question, but he was reasonably sure he'd get an honest answer."

Ah, but what if the truth had been, in the captain's view, that Luckhurst was nowhere near the boat? "I wouldn't have told him, 'You've no bloody chance.' I like to think it is possible to be less brutal than that while being sincere, but I would have told him straight that his chances were slim, or even less than that."

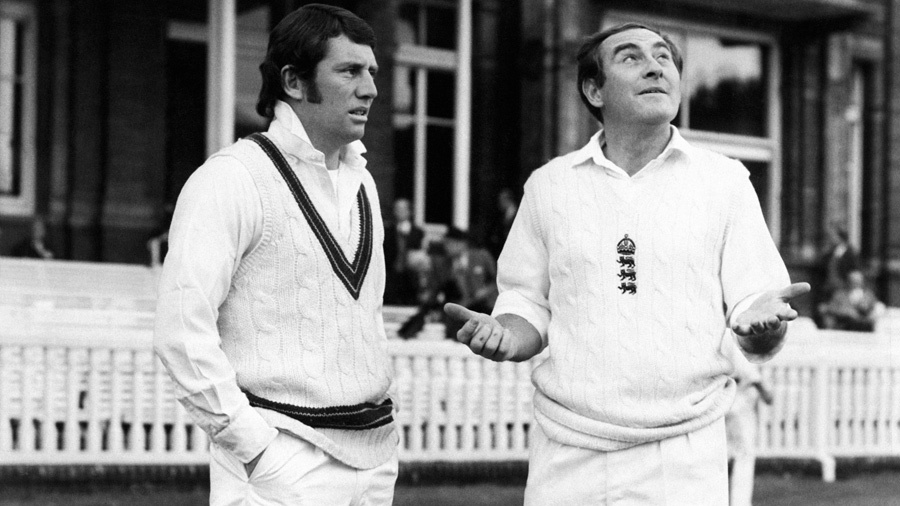

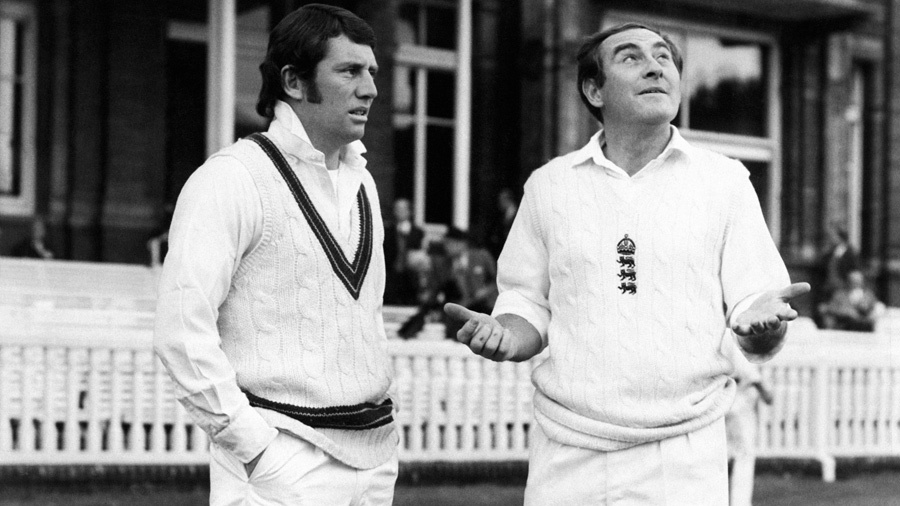

Ray Illingworth (right): "I felt my two strongest points were, first, after playing for quite a time, I knew batsmen pretty well, so I thought I set good fields; and second, I think I was able to get the best out of people" © PA Photos

Ray Illingworth (right): "I felt my two strongest points were, first, after playing for quite a time, I knew batsmen pretty well, so I thought I set good fields; and second, I think I was able to get the best out of people" © PA Photos

So, knowledge of batsmen, intelligence, psychological insight and honesty: all assets that Anderson possesses, and has employed in support of his captains. Unlike most fast bowlers, moreover, he fields in the slips - one of the better vantage points, if perhaps overrated. He says he enjoyed leading Lancashire on a pre-season tour but acknowledges that, as a fast bowler of advanced age, promoting him now would have made little sense. And yes, if we're brutally honest, had the vacancy arisen, say, three years ago, it is questionable whether he could have been relied upon to control the flashes of temper that have occasionally plunged him into hot water.

Brearley, for his part, contended that a fast bowler should only ever be made captain as a last resort. "It takes an exceptional character to know when to bowl, to keep bowling with all his energy screwed up into a ball of aggression, and to be sensitive to the needs of the team, both tactically and psychologically. [Bob] Willis in particular always shut himself up into a cocoon of concentration and fury for his bowling." The exception, he allowed, was Mike Procter. "Vintcent van der Bijl, who played under Procter for Natal, speaks of his ability to develop each player's natural game and of the enthusiasm that he brought to every match."

Benaud disagreed with Brearley, hailing Keith Miller, a fast bowling allrounder, as the best captain he played under. "No one under whom I played sized up a situation more quickly and no one was better at summing up a batsman's weaknesses," Benaud wrote. "He had to do this for himself when he was bowling and it was second nature for him to do so as captain."

Unaccountably to many, while his tenure as New South Wales captain kicked off a run of nine consecutive Sheffield Shield titles, the nearest Miller came to leading his country was when he took over from the injured Ian Johnson for the first Test of the 1954-55 Caribbean tour in Jamaica, which saw him handle his attack astutely over both West Indies innings, score a century and grab five wickets.

Brearley, for his part, contended that a fast bowler should only ever be made captain as a last resort

Naturally, it is pure conjecture as to whether Australia would have fared better under him on the 1956 Ashes tour - Johnson, a so-so offspinner but the establishment man, was again preferred. There seems to be no better explanation for Miller being passed over than that the selectors were fearful that, as a free spirit and renowned party animal in an image-obsessed trade, he might project the wrong one. "I never seriously thought I would be the captain," Miller would reflect. "I'm impulsive; what's more, I've never been Bradman's pin-up." Nearly half a century later, Shane Warne suffered similarly.

Anderson's main thrust, nonetheless, was about bowlers in general. So, is it fair to say that selectors and committees are still blinded by tradition? Not remotely as much as they were. That two-thirds of the longest-reigning Test bowler-captains (and both wicketkeeper-captains) have assumed charge in the post-Packer age seems far from coincidental.

As Tests have proliferated and media scrutiny has soared, so appointing the right man has never been more important; shelving reservations based on ritual has become equally crucial, as evinced most recently by the appointments of Rangana Herath (Sri Lanka), Jason Holder (West Indies) and Graeme Cremer (Zimbabwe) - one of whom, Holder, is a remarkably young fast bowler, albeit not a furiously aggressive specimen. Nevertheless, at a time when central contracts have placed pre-international captaincy experience at an ever-scarcer premium, this open-mindedness, such as it is, must gain pace.

Whatever the future may bring, there is only one certainty: there will never be another Brearley, another accomplished strategist, deep thinker and wise leader of men otherwise unworthy of his place. All the more reason, then, for that revised version of The Art of Captaincy to be mandatory bedtime reading for Joe Root.

James Anderson: one of many who have questioned why more fast bowlers aren't considered for captaincy © Getty Images

James Anderson: one of many who have questioned why more fast bowlers aren't considered for captaincy © Getty ImagesJames Anderson has nothing to prove to anyone but, one assumes, himself. Nor is he one to mince words. So when he expresses disappointment at not having been considered for the England Test captaincy, then says he doesn't know why more fast bowlers aren't entrusted with leadership, and leaves the question hanging in the air, the point is worth considering. What possible reason can there be to maintain the lazy, prejudiced, time-dishonoured view that batsmen should be the default choice as coin-tossers?

Naturally, the record books tell their own flagrantly biased story: of the 57 men to have captained in 25 or more Tests, 46 have been batsmen first and foremost (including 15 of the 16 who have done so on 50-plus occasions, the exception being MS Dhoni). Even if we include two top-notch allrounders, Imran Khan and Garry Sobers, the number of seam bowlers runs to just six: Imran (48 Tests), Sobers (39), Kapil Dev (34), Darren Sammy (30), Shaun Pollock (26) and Wasim Akram (25). Still, that's twice as many representatives in the chart as the spin fraternity can muster - Daniel Vettori (32), Ray Illingworth (31) and Richie Benaud (28) - never mind the stumpers, who contribute only Dhoni (60) and Mushfiqur Rahim (30). As for those who would classify him as a spinner, Sobers is remembered better by this column for his left-arm swing than his spin, so let's indulge it.

It gets worse. Late last year the Cricketer magazine asked readers to vote for their favourite England captain; of the 23 candidates proffered, only Illingworth did not count run-making as his primary occupation. It's all a matter of class, of course. Back when such distinctions were made, the amateurs were almost invariably batsmen, cravat-wearing types accustomed to being served hittable offerings by lowly, gnarly professionals; chaps to whom authority was a birthright. "In England," noted Mike Brearley in his definitive The Art of Captaincy, a revised edition of which is due out this summer, "charisma and leadership have traditionally been associated with the upper class; with that social strata that gives its members what Kingsley Amis called 'the voice accustomed to command'."

If Anderson is "all for bowlers being captains", Don Bradman offered the counter-argument in The Art of Cricket, reasoning that they would lack objectivity about their own workload. "They tend either to over-bowl themselves or not to bowl enough," reinforced Brearley, "from conceit, modesty or indeed self-protection." On the other hand, he continued, two of the best postwar captains in his view were Benaud and Illingworth, outliers both.

It's all a matter of class, of course. Back when such distinctions were made, the amateurs were almost invariably batsmen, cravat-wearing types accustomed to being served hittable offerings by lowly, gnarly professionals

In his 1980 book Captaincy, Illingworth argued that the allrounder, and especially those who were also twirlers like himself and Benaud, were the best equipped for the job. He also took issue with Bradman in his autobiography Yorkshire and Back:

"Basically, I felt my two strongest points were, first, after playing for quite a time I knew batsmen pretty well and I knew their temperaments so I thought I set good fields; and second, I think I was able to get the best out of people because they trusted me. I knew when to attack and when to defend, which governed field placing, and my handling of the bowling."

Video has aided such knowledge, granted, but there's no substitute for a bowler's instinct.

Benaud also rated Illingworth high above the herd. In his 1984 book, Benaud of Reflection he wrote:

"He was a deep thinker on the game, without having any of the theories which sometimes produce woolly thinking from captains. He was a shrewd psychologist and one who left his team in no doubt as to what he required of them. Above all, though, he made his decisions before the critical moment. It was never a case of thinking for an over or two about whether or not a move should be made. If he had a hunch it would work, and if it seemed remotely within the carefully laid-down plans of the series, then he would do it."

What counted above all, felt Illingworth, under whose charge England enjoyed most of their record 26-match unbeaten run between 1969 and 1971, was honesty. During the summer of 1970, opener Brian Luckhurst asked him, somewhat tentatively, whether he had any chance of being picked for that winter's Ashes tour, having made a fair few runs in the first three Tests of the series against a powerful Rest of the World attack. "You're almost on the boat now," replied Illy. "Now what I liked about that," he recollected, "was that Brian had only played three matches with me, and yet he felt that not only could he ask a question, but he was reasonably sure he'd get an honest answer."

Ah, but what if the truth had been, in the captain's view, that Luckhurst was nowhere near the boat? "I wouldn't have told him, 'You've no bloody chance.' I like to think it is possible to be less brutal than that while being sincere, but I would have told him straight that his chances were slim, or even less than that."

Ray Illingworth (right): "I felt my two strongest points were, first, after playing for quite a time, I knew batsmen pretty well, so I thought I set good fields; and second, I think I was able to get the best out of people" © PA Photos

Ray Illingworth (right): "I felt my two strongest points were, first, after playing for quite a time, I knew batsmen pretty well, so I thought I set good fields; and second, I think I was able to get the best out of people" © PA PhotosSo, knowledge of batsmen, intelligence, psychological insight and honesty: all assets that Anderson possesses, and has employed in support of his captains. Unlike most fast bowlers, moreover, he fields in the slips - one of the better vantage points, if perhaps overrated. He says he enjoyed leading Lancashire on a pre-season tour but acknowledges that, as a fast bowler of advanced age, promoting him now would have made little sense. And yes, if we're brutally honest, had the vacancy arisen, say, three years ago, it is questionable whether he could have been relied upon to control the flashes of temper that have occasionally plunged him into hot water.

Brearley, for his part, contended that a fast bowler should only ever be made captain as a last resort. "It takes an exceptional character to know when to bowl, to keep bowling with all his energy screwed up into a ball of aggression, and to be sensitive to the needs of the team, both tactically and psychologically. [Bob] Willis in particular always shut himself up into a cocoon of concentration and fury for his bowling." The exception, he allowed, was Mike Procter. "Vintcent van der Bijl, who played under Procter for Natal, speaks of his ability to develop each player's natural game and of the enthusiasm that he brought to every match."

Benaud disagreed with Brearley, hailing Keith Miller, a fast bowling allrounder, as the best captain he played under. "No one under whom I played sized up a situation more quickly and no one was better at summing up a batsman's weaknesses," Benaud wrote. "He had to do this for himself when he was bowling and it was second nature for him to do so as captain."

Unaccountably to many, while his tenure as New South Wales captain kicked off a run of nine consecutive Sheffield Shield titles, the nearest Miller came to leading his country was when he took over from the injured Ian Johnson for the first Test of the 1954-55 Caribbean tour in Jamaica, which saw him handle his attack astutely over both West Indies innings, score a century and grab five wickets.

Brearley, for his part, contended that a fast bowler should only ever be made captain as a last resort

Naturally, it is pure conjecture as to whether Australia would have fared better under him on the 1956 Ashes tour - Johnson, a so-so offspinner but the establishment man, was again preferred. There seems to be no better explanation for Miller being passed over than that the selectors were fearful that, as a free spirit and renowned party animal in an image-obsessed trade, he might project the wrong one. "I never seriously thought I would be the captain," Miller would reflect. "I'm impulsive; what's more, I've never been Bradman's pin-up." Nearly half a century later, Shane Warne suffered similarly.

Anderson's main thrust, nonetheless, was about bowlers in general. So, is it fair to say that selectors and committees are still blinded by tradition? Not remotely as much as they were. That two-thirds of the longest-reigning Test bowler-captains (and both wicketkeeper-captains) have assumed charge in the post-Packer age seems far from coincidental.

As Tests have proliferated and media scrutiny has soared, so appointing the right man has never been more important; shelving reservations based on ritual has become equally crucial, as evinced most recently by the appointments of Rangana Herath (Sri Lanka), Jason Holder (West Indies) and Graeme Cremer (Zimbabwe) - one of whom, Holder, is a remarkably young fast bowler, albeit not a furiously aggressive specimen. Nevertheless, at a time when central contracts have placed pre-international captaincy experience at an ever-scarcer premium, this open-mindedness, such as it is, must gain pace.

Whatever the future may bring, there is only one certainty: there will never be another Brearley, another accomplished strategist, deep thinker and wise leader of men otherwise unworthy of his place. All the more reason, then, for that revised version of The Art of Captaincy to be mandatory bedtime reading for Joe Root.

Monday, 20 February 2017

Cricket Captains aren't that important anymore. Same for high paid Business Leaders

Tim Wigmore in Cricinfo

It has been a seminal fortnight for the England cricket team. The country has a new Test match captain, and Joe Root's appointment could herald obvious changes to the team's approach, on and off the field. Yet whether the change of captaincy will have any positive or negative effect on results is an altogether different matter.

How much does individual leadership really matter? It's a question valid in cricket, sport and beyond.

"Being in charge isn't what it used to be," writes Moisés Naím in The End of Power. He shows how, for all the focus on the figureheads of teams, the powers of leaders are being eroded, in everything from business to politics and the military. "In the 21st century, power is easier to get, harder to use - and easier to lose," Naím says, arguing that, because of the digital revolution, the collapse of deference, and increased accountability within organisations, the powerful now face more limitations on their power than ever before. In the second half of the 20th century, weaker sides (in terms of soldiers and weapons) achieved their strategic goals in the majority of wars. The tenures of chief executives are becoming shorter, and those in charge also face more internal constraints on their power than ever before.

The most successful leaders have never been more venerated: the leadership-coaching industry is worth an estimated US$50 billion every year, brimming with corporate bigwigs attempting to learn the "lessons" of other leaders' success. Yet there is no real evidence of the enduring superstar qualities of those who cash in. Award-winning chief executives subsequently underperform, both against their own performance and against non-prize-winning CEOs, as research by Ulrike Malmendier and Geoffrey Tate shows. A lot of the lauded CEOs' previous success, in other words, might have been simply luck, and their subsequent underperformance regression to the mean.

The obsession with leadership extends to sport, yet leaders' power is being reduced here also. "In early-modern sports - the late 19th century - there was little or no coaching and hence the captain on the field had a significant leadership role to play," explains the sports economist and historian Stefan Szymanski. "As sport became more organised and coaching strategy developed, the role of the captain on the field diminished."

Compared with other sports, cricket is unusual in giving as much power to the captain as it does. Yet the cricket captain has not been immune to the wider erosion in the importance of leadership across sport. "The role is declining as the potential of coaches to add analytical support based on data analysis has increased," Szymanski says.

It is instructive to compare the responsibility of Mike Brearley to that of Root today. While Root will be supported by a coterie of coaches, physiologists and analysts, Brearley operated before the modern coach, and had to oversee warming up and stretching before each day. In the days of amateurism, captains even had to motivate amateurs to play at all. Today the captain is far more important in club cricket, where they have no coaches to aid them and often face an arduous task to even get a full team together, than in the professional game.

The power of individual coaches has also been diminished, because the responsibilities that were once the preserve of one man are now divided up among a multitude of personnel. In international cricket teams today, what were, 25 years ago, the sole functions of the coach are now divided up among what often amounts to a 2nd XI of support staff.

While the narrative of football's Premier League now revolves around managers, each result explored through the prism of their success or failure, perhaps they have never mattered less. In the 1930s, Arsenal manager Herbert Chapman not merely coached innovatively but led Arsenal to introduce numbered shirts, and build floodlights and a new stand. Unless they are named Arsene Wenger, the average Premier League manager now lasts a year in the job. Given the complexities of modern sport, there is a limit to what they can do. Indeed, studies of poorly performing clubs find that performances improve by an almost identical amount whether or not a new manager is appointed. The new boss, then, is rarely much better or worse than the old boss.

The book Soccernomics finds a 90% correlation between wage bills and league finishes over a ten-year period; just 10% of top-flight managers consistently overachieve when wages are factored into account. So, brilliant leadership can make a difference, but only in exceptional cases. It was not merely modesty that led Yogi Berra, when asked what made a great baseball coach, to reply: "A great ball team."

Joe Root will enjoy the services of several coaches, analysts and managers in his role as England's Test captain, thereby diffusing his leadership responsibilities © Getty Images

Joe Root will enjoy the services of several coaches, analysts and managers in his role as England's Test captain, thereby diffusing his leadership responsibilities © Getty Images

The captain in golf's Ryder Cup has a job akin to the coach in other sports. It offers a prime example of how narratives are constructed around the leader, assigning them more power than they really have. In The Captain Myth, Richard Gillis explores how victories or defeats are retrospectively explained through a captain's mistakes or shrewd decisions. Every match must consist of a Good Captain and Bad Captain, and the Good Captain is always the victor. The trouble with this simplistic narrative is that, as Paul Azinger, who led the US to victory in the 2008 Ryder Cup, reflects, "There have been some captains who have micro-managed everything and lost. There have been captains who were drunk every night and won. There is no blueprint on winning."

There is a paradox to leadership in modern sport. Leaders have never faced more scrutiny - but most have never had less power. Professionalism and the explosion of money in sport means that decisions once the sole preserve of a captain or head coach are now influenced by dozens of others behind the scenes: specialist coaches, performance analysts who mine data, dieticians, psychologists and those responsible for nurturing academy players. Perhaps the cricket team that has performed most above themselves in recent years is Northamptonshire in the T20 Blast. Reaching three finals in four years has not just been a triumph for Alex Wakely's astute captaincy, but also for the coaching staff, the data analyst, the physio and all those involved in player recruitment.

The reluctance to recognise the limits of leadership has deep roots. We are a storytelling species. People make for much better stories than underlying, impersonal factors; Soccernomics shows that success in international football can broadly be explained by three factors - population size, GDP, and experience playing the sport - that have nothing to do with leadership. In The Captain Myth, Gillis writes that, because of psychological biases "meshed with our obsession with celebrity, it's easy to understand how the captain has become such a prominent figure in the sports world". In cricket, he tells me that "the decisions of the captain can be significant, but the relationship between the decisions and the outcome is not linear, it's far messier than that, and makes a far less enjoyable tale".

As much as coaches and fans crave inspirational leadership, in modern sport, with huge and complex professional structures to manage, perhaps it is easier for a single leader to make a negative difference than a positive one. "Good captaincy and coaching have far less of an impact on outcomes than bad captaincy and coaching does," believes Trent Woodhill, a leading T20 coach. Bad leadership can marginalise and disempower the backroom team, effectively preventing support staff from doing their jobs properly. Beyond sport, Naím believes that we are in an age of "heightened vulnerability to bad ideas and bad leaders". The analysis extends beyond sport. Disruptive technology has not only changed the nature of power, Naím believes, but also led to an age of "heightened vulnerability to bad ideas and bad leaders".

Root has captained in just four first-class games, yet this is in keeping with modern norms. That Virat Kohli, Steven Smith and Kane Williamson have all been successful after their appointments as captain, despite a derisory amount of prior leadership experience in professional sport, suggests that captaincy experience - and, by implication, captaincy skill - is simply not that important. The absence of specialist captains, at both domestic and international level, also reflects a recognition of the limits of what a skipper can achieve.

"Playing in the middle and understanding the demands is more important than captaincy," Andrew Strauss said when Root was unveiled. The greatest potential boon of a Root captaincy lies not in a new culture he might create, or more enterprising leadership, but the possibility of greater run-scoring: if Alastair Cook is reinvigorated without the leadership, while, in keeping with recent England captains, Root's own batting initially enjoys an upswing.

Leadership is not irrelevant. Occasionally cricketers are particularly suited to a leadership role - Brearley, Graeme Smith, or Misbah-ul-Haq, say; some, like Kevin Pietersen, might be the opposite. But the overwhelming majority of captains are bunched in the middle - and, in any case, a captain's ability to do good is marginal, now more than ever. For all the tendency to focus on a team's figurehead, great leadership is a collective endeavour, and operates against wider limitations. Perhaps this is why Strauss is so unperturbed by Root's lack of captaincy experience. Only rarely does the identity of a captain really matter.

It has been a seminal fortnight for the England cricket team. The country has a new Test match captain, and Joe Root's appointment could herald obvious changes to the team's approach, on and off the field. Yet whether the change of captaincy will have any positive or negative effect on results is an altogether different matter.

How much does individual leadership really matter? It's a question valid in cricket, sport and beyond.

"Being in charge isn't what it used to be," writes Moisés Naím in The End of Power. He shows how, for all the focus on the figureheads of teams, the powers of leaders are being eroded, in everything from business to politics and the military. "In the 21st century, power is easier to get, harder to use - and easier to lose," Naím says, arguing that, because of the digital revolution, the collapse of deference, and increased accountability within organisations, the powerful now face more limitations on their power than ever before. In the second half of the 20th century, weaker sides (in terms of soldiers and weapons) achieved their strategic goals in the majority of wars. The tenures of chief executives are becoming shorter, and those in charge also face more internal constraints on their power than ever before.

The most successful leaders have never been more venerated: the leadership-coaching industry is worth an estimated US$50 billion every year, brimming with corporate bigwigs attempting to learn the "lessons" of other leaders' success. Yet there is no real evidence of the enduring superstar qualities of those who cash in. Award-winning chief executives subsequently underperform, both against their own performance and against non-prize-winning CEOs, as research by Ulrike Malmendier and Geoffrey Tate shows. A lot of the lauded CEOs' previous success, in other words, might have been simply luck, and their subsequent underperformance regression to the mean.

The obsession with leadership extends to sport, yet leaders' power is being reduced here also. "In early-modern sports - the late 19th century - there was little or no coaching and hence the captain on the field had a significant leadership role to play," explains the sports economist and historian Stefan Szymanski. "As sport became more organised and coaching strategy developed, the role of the captain on the field diminished."

Compared with other sports, cricket is unusual in giving as much power to the captain as it does. Yet the cricket captain has not been immune to the wider erosion in the importance of leadership across sport. "The role is declining as the potential of coaches to add analytical support based on data analysis has increased," Szymanski says.

It is instructive to compare the responsibility of Mike Brearley to that of Root today. While Root will be supported by a coterie of coaches, physiologists and analysts, Brearley operated before the modern coach, and had to oversee warming up and stretching before each day. In the days of amateurism, captains even had to motivate amateurs to play at all. Today the captain is far more important in club cricket, where they have no coaches to aid them and often face an arduous task to even get a full team together, than in the professional game.

The power of individual coaches has also been diminished, because the responsibilities that were once the preserve of one man are now divided up among a multitude of personnel. In international cricket teams today, what were, 25 years ago, the sole functions of the coach are now divided up among what often amounts to a 2nd XI of support staff.

While the narrative of football's Premier League now revolves around managers, each result explored through the prism of their success or failure, perhaps they have never mattered less. In the 1930s, Arsenal manager Herbert Chapman not merely coached innovatively but led Arsenal to introduce numbered shirts, and build floodlights and a new stand. Unless they are named Arsene Wenger, the average Premier League manager now lasts a year in the job. Given the complexities of modern sport, there is a limit to what they can do. Indeed, studies of poorly performing clubs find that performances improve by an almost identical amount whether or not a new manager is appointed. The new boss, then, is rarely much better or worse than the old boss.

The book Soccernomics finds a 90% correlation between wage bills and league finishes over a ten-year period; just 10% of top-flight managers consistently overachieve when wages are factored into account. So, brilliant leadership can make a difference, but only in exceptional cases. It was not merely modesty that led Yogi Berra, when asked what made a great baseball coach, to reply: "A great ball team."

Joe Root will enjoy the services of several coaches, analysts and managers in his role as England's Test captain, thereby diffusing his leadership responsibilities © Getty Images

Joe Root will enjoy the services of several coaches, analysts and managers in his role as England's Test captain, thereby diffusing his leadership responsibilities © Getty ImagesThe captain in golf's Ryder Cup has a job akin to the coach in other sports. It offers a prime example of how narratives are constructed around the leader, assigning them more power than they really have. In The Captain Myth, Richard Gillis explores how victories or defeats are retrospectively explained through a captain's mistakes or shrewd decisions. Every match must consist of a Good Captain and Bad Captain, and the Good Captain is always the victor. The trouble with this simplistic narrative is that, as Paul Azinger, who led the US to victory in the 2008 Ryder Cup, reflects, "There have been some captains who have micro-managed everything and lost. There have been captains who were drunk every night and won. There is no blueprint on winning."

There is a paradox to leadership in modern sport. Leaders have never faced more scrutiny - but most have never had less power. Professionalism and the explosion of money in sport means that decisions once the sole preserve of a captain or head coach are now influenced by dozens of others behind the scenes: specialist coaches, performance analysts who mine data, dieticians, psychologists and those responsible for nurturing academy players. Perhaps the cricket team that has performed most above themselves in recent years is Northamptonshire in the T20 Blast. Reaching three finals in four years has not just been a triumph for Alex Wakely's astute captaincy, but also for the coaching staff, the data analyst, the physio and all those involved in player recruitment.

The reluctance to recognise the limits of leadership has deep roots. We are a storytelling species. People make for much better stories than underlying, impersonal factors; Soccernomics shows that success in international football can broadly be explained by three factors - population size, GDP, and experience playing the sport - that have nothing to do with leadership. In The Captain Myth, Gillis writes that, because of psychological biases "meshed with our obsession with celebrity, it's easy to understand how the captain has become such a prominent figure in the sports world". In cricket, he tells me that "the decisions of the captain can be significant, but the relationship between the decisions and the outcome is not linear, it's far messier than that, and makes a far less enjoyable tale".

As much as coaches and fans crave inspirational leadership, in modern sport, with huge and complex professional structures to manage, perhaps it is easier for a single leader to make a negative difference than a positive one. "Good captaincy and coaching have far less of an impact on outcomes than bad captaincy and coaching does," believes Trent Woodhill, a leading T20 coach. Bad leadership can marginalise and disempower the backroom team, effectively preventing support staff from doing their jobs properly. Beyond sport, Naím believes that we are in an age of "heightened vulnerability to bad ideas and bad leaders". The analysis extends beyond sport. Disruptive technology has not only changed the nature of power, Naím believes, but also led to an age of "heightened vulnerability to bad ideas and bad leaders".

Root has captained in just four first-class games, yet this is in keeping with modern norms. That Virat Kohli, Steven Smith and Kane Williamson have all been successful after their appointments as captain, despite a derisory amount of prior leadership experience in professional sport, suggests that captaincy experience - and, by implication, captaincy skill - is simply not that important. The absence of specialist captains, at both domestic and international level, also reflects a recognition of the limits of what a skipper can achieve.

"Playing in the middle and understanding the demands is more important than captaincy," Andrew Strauss said when Root was unveiled. The greatest potential boon of a Root captaincy lies not in a new culture he might create, or more enterprising leadership, but the possibility of greater run-scoring: if Alastair Cook is reinvigorated without the leadership, while, in keeping with recent England captains, Root's own batting initially enjoys an upswing.

Leadership is not irrelevant. Occasionally cricketers are particularly suited to a leadership role - Brearley, Graeme Smith, or Misbah-ul-Haq, say; some, like Kevin Pietersen, might be the opposite. But the overwhelming majority of captains are bunched in the middle - and, in any case, a captain's ability to do good is marginal, now more than ever. For all the tendency to focus on a team's figurehead, great leadership is a collective endeavour, and operates against wider limitations. Perhaps this is why Strauss is so unperturbed by Root's lack of captaincy experience. Only rarely does the identity of a captain really matter.

Tuesday, 25 October 2016

How to be a vice-captain

Brad Haddin in Cricinfo

Wind the clock back to March 2013. I'm boarding a flight home from India with Michael Clarke. He's out of the final Test of that series in Delhi with a back flare-up, while I'm travelling home after being the injury replacement for Matthew Wade in Mohali.

Plenty has gone on in the preceding week or so, the "homework"-related suspensions of Shane Watson, Mitchell Johnson, Usman Khawaja and James Pattinson in particular. So we take the opportunity to speak pretty openly about how the team is functioning, and how unhappy everyone is with the way the Indian tour has panned out, in the way some players have been treated and the mood around the team.

For one thing, expectations of behaviour seem to be driven by management rather than players, and that's something that needs to change.

Mickey Arthur is yet to be replaced by Darren Lehmann, but it's an important conversation in terms of how Michael thinks the team should operate in the coming months. It helps too that having been away from the team for a while, I can see things from an angle Michael isn't seeing. One change in the interim is the much more experienced side chosen for the Ashes tour that follows.

While I did not officially hold the title at the time, that's a good example of how a deputy should operate. Vice-captaincy is a low-profile job that's not fully understood by many, but it is vital to helping get a successful team moving in the right direction together. One bedrock of the gig is to have a deputy committed to that role, rather than thinking about being captain himself. That was certainly the case with me.

The other foundation of the job is a relationship with the captain that allows you to speak frankly with him about where the team is going - in private rather than in front of the team. Keeping an ear to the ground and communicating with other players and then relaying that to the leader when necessary. Having gone back a long way with Michael, we had that sort of dynamic.

These conversations should be honest enough to be able to say, "I don't think this is working, and this is how the group is feeling", or "I think you might have missed this". These aren't always the easiest conversations, but they have to happen from a place of mutual respect. The captain can either take note or disregard it, but the main thing is that he knows how things are tracking when he does make his final call on a given issue. That doesn't happen without a healthy relationship between captain and deputy.

Overall, the role of the vice-captain is to complement what the captain does. Your job is to make sure the younger guys are feeling a part of the team and that they understand the standards that you want to set in the group and that your behaviour is not to be compromised.

You pick up on the little things around the team, like being punctual, wearing the right uniforms and treating people inside and outside the team with respect, and have a quiet word to guys here and there if they need a reminder. That then flows into attention to detail in the middle.

Michael was a very good tactical captain who was always in control on the field. My job, relative to him - and similarly for other senior players - was to make sure the mood of the team was right, and to set standards for the younger guys to follow; to be sure they knew what it meant to be an Australian cricketer. The vice-captain should be the guy to drive that.

Once we got to England in 2013, I took it upon myself to spend time with each player to talk about the brand of cricket we wanted to play and also to make sure guys were talking and reflecting on the game and each other, whether we'd had a good day or a bad day.

We did that after a close loss in the first Test at Trent Bridge and that was a good moment - we weren't retreating into ourselves in defeat. Once again, that flowed well into the success we had later, because guys were talking and enjoying each other's good days, having commiserated through the bad ones.

For a long time in cricket, I think that sort of thing happened pretty organically. But in an era when the game is so professionalised and guys are jetting around playing T20 tournaments when not with Australia or even their domestic teams, it takes thoughtful effort to make sure it still happens. If anything, vice-captaincy has grown in importance for that reason.

I mentioned earlier that one key to the job is not wanting the captaincy. If you look back through the recent history of Australian cricket, the examples are plentiful. Geoff Marsh was a terrific lieutenant to Allan Border, Ian Healy to Mark Taylor, and Adam Gilchrist to Ricky Ponting.

Once we got to England in 2013, I took it upon myself to spend time with each player to talk about the brand of cricket we wanted to play

They are three contrasting characters, but what they had in common was no great desire to be captain. I saw Gilly's work up close as a junior member of the squad, and he was a terrific link man between the leadership and the team. As fellow glovemen, I also saw how the role behind the stumps gave you a great perspective to support the captain.

There have been other times, of course, when the vice-captain is the heir-apparent. That was the case for Taylor, when he was deputy to AB, for Steve Waugh, when he replaced Heals as vice-captain to Taylor, and for Michael, when he was appointed deputy to Ricky after Gilly retired. All those guys will tell you that it put them in awkward positions at times, not knowing whether to intervene in things or not, whether on or off the field.

Similarly, Watson had a difficult time as Michael's deputy because they did not have the same open relationship to discuss things that I was fortunate enough to have. That's something for Cricket Australia to keep in mind whenever it makes these appointments.

Right now, Steven Smith has an able deputy in David Warner. To me, this relationship should work because, like Michael and I, these two have known each other for years. Davey is growing into the role at present, evolving from his former "attack dog" persona into someone more measured. If he ever wants a reminder of how vice-captaincy should or shouldn't work, he needs only to think back to a year like 2013 and the team's contrasting fortunes.

Wind the clock back to March 2013. I'm boarding a flight home from India with Michael Clarke. He's out of the final Test of that series in Delhi with a back flare-up, while I'm travelling home after being the injury replacement for Matthew Wade in Mohali.

Plenty has gone on in the preceding week or so, the "homework"-related suspensions of Shane Watson, Mitchell Johnson, Usman Khawaja and James Pattinson in particular. So we take the opportunity to speak pretty openly about how the team is functioning, and how unhappy everyone is with the way the Indian tour has panned out, in the way some players have been treated and the mood around the team.

For one thing, expectations of behaviour seem to be driven by management rather than players, and that's something that needs to change.

Mickey Arthur is yet to be replaced by Darren Lehmann, but it's an important conversation in terms of how Michael thinks the team should operate in the coming months. It helps too that having been away from the team for a while, I can see things from an angle Michael isn't seeing. One change in the interim is the much more experienced side chosen for the Ashes tour that follows.

While I did not officially hold the title at the time, that's a good example of how a deputy should operate. Vice-captaincy is a low-profile job that's not fully understood by many, but it is vital to helping get a successful team moving in the right direction together. One bedrock of the gig is to have a deputy committed to that role, rather than thinking about being captain himself. That was certainly the case with me.

The other foundation of the job is a relationship with the captain that allows you to speak frankly with him about where the team is going - in private rather than in front of the team. Keeping an ear to the ground and communicating with other players and then relaying that to the leader when necessary. Having gone back a long way with Michael, we had that sort of dynamic.

These conversations should be honest enough to be able to say, "I don't think this is working, and this is how the group is feeling", or "I think you might have missed this". These aren't always the easiest conversations, but they have to happen from a place of mutual respect. The captain can either take note or disregard it, but the main thing is that he knows how things are tracking when he does make his final call on a given issue. That doesn't happen without a healthy relationship between captain and deputy.

Overall, the role of the vice-captain is to complement what the captain does. Your job is to make sure the younger guys are feeling a part of the team and that they understand the standards that you want to set in the group and that your behaviour is not to be compromised.

You pick up on the little things around the team, like being punctual, wearing the right uniforms and treating people inside and outside the team with respect, and have a quiet word to guys here and there if they need a reminder. That then flows into attention to detail in the middle.

Michael was a very good tactical captain who was always in control on the field. My job, relative to him - and similarly for other senior players - was to make sure the mood of the team was right, and to set standards for the younger guys to follow; to be sure they knew what it meant to be an Australian cricketer. The vice-captain should be the guy to drive that.

Once we got to England in 2013, I took it upon myself to spend time with each player to talk about the brand of cricket we wanted to play and also to make sure guys were talking and reflecting on the game and each other, whether we'd had a good day or a bad day.

We did that after a close loss in the first Test at Trent Bridge and that was a good moment - we weren't retreating into ourselves in defeat. Once again, that flowed well into the success we had later, because guys were talking and enjoying each other's good days, having commiserated through the bad ones.

For a long time in cricket, I think that sort of thing happened pretty organically. But in an era when the game is so professionalised and guys are jetting around playing T20 tournaments when not with Australia or even their domestic teams, it takes thoughtful effort to make sure it still happens. If anything, vice-captaincy has grown in importance for that reason.

I mentioned earlier that one key to the job is not wanting the captaincy. If you look back through the recent history of Australian cricket, the examples are plentiful. Geoff Marsh was a terrific lieutenant to Allan Border, Ian Healy to Mark Taylor, and Adam Gilchrist to Ricky Ponting.

Once we got to England in 2013, I took it upon myself to spend time with each player to talk about the brand of cricket we wanted to play

They are three contrasting characters, but what they had in common was no great desire to be captain. I saw Gilly's work up close as a junior member of the squad, and he was a terrific link man between the leadership and the team. As fellow glovemen, I also saw how the role behind the stumps gave you a great perspective to support the captain.

There have been other times, of course, when the vice-captain is the heir-apparent. That was the case for Taylor, when he was deputy to AB, for Steve Waugh, when he replaced Heals as vice-captain to Taylor, and for Michael, when he was appointed deputy to Ricky after Gilly retired. All those guys will tell you that it put them in awkward positions at times, not knowing whether to intervene in things or not, whether on or off the field.

Similarly, Watson had a difficult time as Michael's deputy because they did not have the same open relationship to discuss things that I was fortunate enough to have. That's something for Cricket Australia to keep in mind whenever it makes these appointments.

Right now, Steven Smith has an able deputy in David Warner. To me, this relationship should work because, like Michael and I, these two have known each other for years. Davey is growing into the role at present, evolving from his former "attack dog" persona into someone more measured. If he ever wants a reminder of how vice-captaincy should or shouldn't work, he needs only to think back to a year like 2013 and the team's contrasting fortunes.

Thursday, 7 January 2016

Hashim Amla did the honourable thing by jettisoning his burden

Mike Selvey in The Guardian

It may be unusual to change captains at the midpoint of a series but Hashim Amla has chosen a good moment to concede his position and drop back into the ranks. A resignation after the massive defeat in Durban would have represented capitulation even if he had been contemplating it for a while.

Now though he has done so on the back of a stirring fightback from the side he led, and an emphatic return not so much to form (he had not looked out of touch in the second innings in Durban) as to relentless run-gathering. It is a little too strong to describe the outcome of a Test that had yet to complete its third innings as a “winning draw” for South Africa. With the conditions finally giving the bowlers some lateral movement on the final day, we can only surmise what the England bowlers might have managed had they been defending, say, 200 and their colleagues rediscovered the art of catching but at least we know there will be an almighty scrap now up on the highveld.