Ian Chappell in Cricinfo

It's not only the range of strokes that has dramatically evolved in short-format batting but also the mental approach. Contrast the somnambulistic approach of Essex's Brian Ward in a 1969 40-over game with England's record-breaking assault on the Australian bowling at Trent Bridge recently.

Ward decided that Somerset offspinner Brian Langford was the danger man in the opposition attack, and eight consecutive maidens resulted, handing the bowler the never-to-be-repeated figures of 8-8-0-0. On the other hand England's batsmen this year displayed no such inhibitions in rattling up 481 off 50 overs, and Australia's bowlers, headed by Andrew Tye, with 9-0-100-0, were pummelled.

Nevertheless one thing has remained constant in the short formats: a wariness around spin bowling, although currently it's more likely to be the wrist variety than fingerspin.

The list of successful wristspinners in short-format cricket is growing rapidly and there have been some outstanding recent performances. Afghanistan's Rashid Khan was the joint leading wicket-taker in the BBL; England's Adil Rashid (along with spin-bowling companion Moeen Ali), took the most wicketsin the recent whitewash of Australia; and in successive T20Is against England, India's duo of Yuzvendra Chahal and Kuldeep Yadav have claimed the rare distinction of a five-wicket haul. It's a trail of destruction that have would gladdened the heart of Bill "Tiger" O'Reilly, a great wristspinner himself and the most insistent promoter of the art there has ever been.

Wristspinners are extremely successful in the shorter formats and are being eagerly sought after for the many T20 leagues. Their enormous success is mostly down to the deception they provide, since they are able to turn it from both leg and off with only a minimal change of action. Kuldeep provided a perfect example when he bamboozled both Jonny Bairstow and Joe Root with successive wrong'uns in the opening T20 at Old Trafford.

The fact that Bairstow - a wicketkeeper by trade - was deceived by the wrong'un is symptomatic of a malaise that is sweeping international batting - a general inability to read wristspinners. This failing is not only the root cause of wicket loss from mishits but also contributes to a desirable bowling economy rate for the bowlers, as batsmen are hesitant to attack a delivery they are unsure about. This inability to read wristspinners is mystifying.

If a batsman watches the ball out of the hand, the early warning signals are available. A legbreak is delivered with the back of the hand turned towards the bowler's face, while with the wrong'un, it's facing the batsman. As a further indicator, the wrong'un, because it's bowled out of the back of the hand, has a slightly loftier trajectory. Final confirmation is provided by the seam position, which is tilted towards first slip for the legspinner, and leg slip for the wrong'un. Any batsman waiting to pick the delivery off the pitch is depriving himself of scoring opportunities and putting his wicket in danger.

When Shane Warne was at his devastating peak, fans marvelled at his repertoire and said it was the main reason for his success. "Picking him is the easy part," I explained, "it's playing him that's difficult."

Richie Benaud, another master of the art, summed up spin bowling best: "It's the subtle variations," he proffered, "that bring the most success."

O'Reilly was not only an aggressive leggie but also a wily one, and he bent his back leg when he wanted to vary his pace. This action altered his release point without slowing his arm speed, and consequently it was difficult for the batsman to detect the subtle variation.

This type of information is crucial to successful batsmanship, but following Kuldeep's demolition job, Jos Buttler said it might take one or two games for English batsmen to get used to the left-armer. This is an indictment of the current system for developing young batsmen, where you send them into international battle minus a few important tools.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label batsman. Show all posts

Showing posts with label batsman. Show all posts

Sunday, 8 July 2018

Wednesday, 7 March 2018

On Batting: What does a batsman see?

S B Tang in Cricinfo

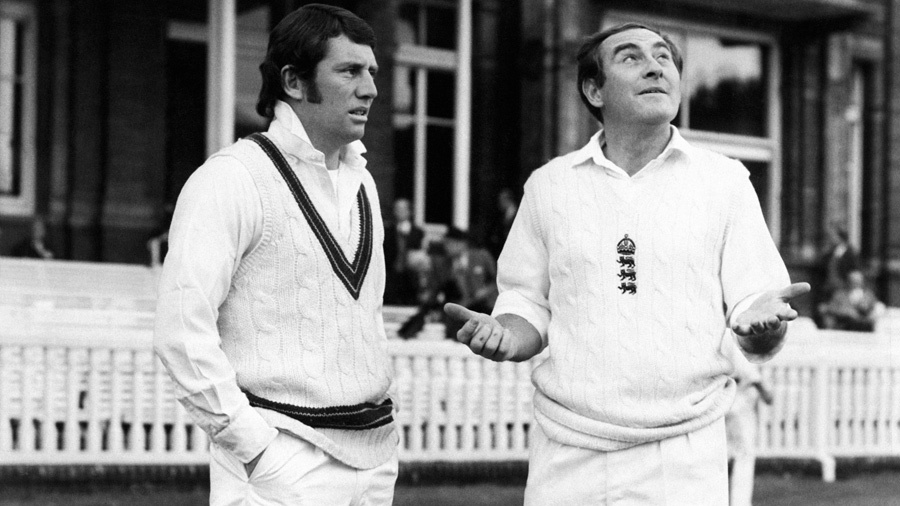

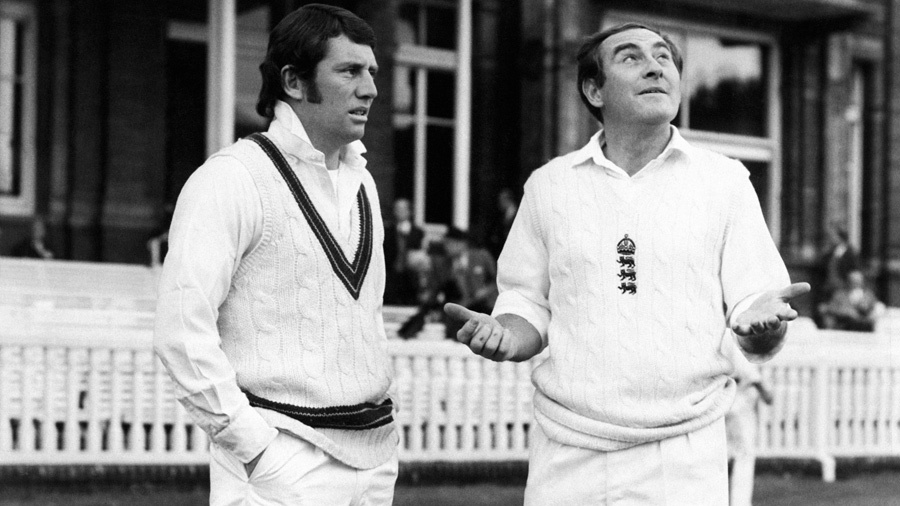

It is late December 1971. A tall, 23-year-old South Australian by the name of Greg Chappell walks down the ornate wood-and-iron staircase of Hadley's Orient Hotel in Hobart. He is meeting his older brother Ian for dinner. The two have been parachuted in to bolster a Tasmania Combined XI for their first-class match against a star-studded World XI featuring Sunil Gavaskar, Garry Sobers, Bishan Bedi and Zaheer Abbas at the Tasmania Cricket Association Ground.

The younger of the two Chappells follows the staircase as it takes a 90-degree left turn, walks past the large portrait of a young Queen Victoria and emerges into the beautiful red-and-gold carpeted lobby of the hotel built by convicts more than a century ago. Ian is running late, as usual. Greg, on time as usual, waits patiently. The concierge approaches him. "Mr Chappell," he says, "there's a letter for you." Greg immediately recognises the handwriting on the envelope - it belongs to his father.

He doesn't know it, but the contents of this envelope will change his life. There's no letter inside, just a newspaper clipping - an opinion article by the Adelaide Advertiser's chief cricket writer, Keith Butler. It says that Chappell is wasting his enormous talent and the way he's batting he won't make the forthcoming Ashes tour. At the end of the article he sees the one-line message his father has written: "I don't believe everything that Keith says, but it might be worth thinking about."

Suddenly, Greg doesn't feel hungry at all. "Mate," he tells Ian when he arrives in the lobby, "I'm just going to stay in." He walks back upstairs. He doesn't turn on the lights. In a corner of his single room, there is an upholstered chair. He sits down on it in the dark, alone, and thinks. He thinks about every single game of cricket that he has ever played, from his very first in the backyard with his brother Ian, to park and beach cricket with his mates, to schoolboys' cricket for Prince Alfred College, to grade cricket for Glenelg District Cricket Club, to Sheffield Shield cricket for South Australia, to county cricket for Somerset, to Test cricket for Australia.

What he seeks is nothing less than the answer to the question that has plagued every batsman since the dawn of time: what is the cause of the massive performance differential between my good days and my bad days? What exactly is it that I'm doing better on my good days than on my bad days?

As he searches his mind for the answer, he enters a deep meditative state. Time passes quickly. Hours later - it is difficult for him to tell how many - he emerges with a stunning realisation: by playing cricket since the age of four, he had, without realising it, developed a systemic process of concentration and a precise method of watching the ball; but he had only been using them consistently on his good days.

There lay the answer to his question: all he had to do was use his own systemic process of concentration and precise method of watching the ball every single time he walked out to bat.

From that day forth, he stops mindlessly hitting balls in training. Instead, he focuses on his process of concentration and method of watching the ball. The aim is to be able to use that mental routine against every single ball that he faces in a match. Five days after his epiphany in Hobart, he gets the opportunity to apply his newfound theory in a match. He is called up to play for Australia - captained by Ian - in their third unofficial Test against the Sobers-captained World XI at the MCG, starting on New Year's Day 1972.

In Australia's first innings, he scores an unbeaten 115. Eight days later, he scores an unbeaten 197 at the SCG in the fourth unofficial Test. As he walks off to the applause of the 19,125-strong crowd, he knows deep down that his batting has gone to an entirely different level. At the tender age of 23, he has discovered what most batsmen spend their entire careers searching fruitlessly for: the secret - for him, anyway - to scoring runs at Test level.

Before his epiphany in Hobart, Chappell scored 243 runs in five Tests at an average of 34.71. After his epiphany, he scored 6867 runs - including 23 hundreds - in 82 Tests at an average of 54.93.

The mental routine that enabled Chappell, in an era when Test bowling was arguably the strongest that it has ever been, to maintain a Test average in excess of 50 for nearly a decade is not particularly complicated.

It starts with the logical principle that mental energy is a finite resource that a batsman must conserve if he is to achieve his ultimate objective of scoring as many runs as possible, which will require him to spend hours, if not days, out in the middle.

After his revelation in Hobart, Greg Chappell made more than 6500 runs at 54.93 © Getty Images

"I have no doubt," Chappell says, "that what allowed me to achieve what I achieved was the fact that I was lucky enough to have learned early in my career that it was about… my mind, not my body. And my subconscious mind was a better cricketer than I could ever be, so what I had to do was get the conscious mind out of the way… give it a job to do - watch his face, watch the [window of release] - and allow my subconscious mind to react to what came."

He saw that the mistake that most batsmen make, especially when they are striving to fulfil their lifelong dream of playing Test cricket for their country, is that they try too hard. They stop trusting the natural instincts that have got them that far and start worrying about getting out, or fretting about the correctness or otherwise of their technique.

At club level, the mistake of trying too hard manifests itself in an even more fundamental error - watching the ball too hard. Former Australia batsman Greg Blewett vividly recalls playing against some grade batsmen who never took their eyes off the ball while they were on strike. They would "watch the ball go from the keeper's hands to first slip, from first slip to point, point to cover, cover to mid-off [and mid-off to the bowler's hands]". Then they would keep watching the ball in the bowler's hands from the top of his run-up to the point of release.

According to Chappell's theory, that method of narrowly watching the ball creates at least four substantive problems.

Firstly, the batsman burns through his finite quantum of mental energy at a rapid rate.

Secondly, watching the ball in the bowler's hand as he is running in has the potential to destabilise a batsman's eyes. "Some bowlers run in and their arms are going everywhere," explains Blewett, a follower of Chappell's theory in the back end of his playing career and now an advocate of it as the head coach of South Australia Under-19s and an assistant coach of South Australia and Adelaide Strikers. "It'd be really hard to focus on that ball [because] your eyes would be darting all over the place."

Thirdly, if the batsman watches the ball in the bowler's hand as he's running in then once the bowler jumps into his delivery stride, he will have to quickly shift his central vision from the ball in the bowler's hand next to his thigh up to the area above his head from which he will release the ball. That is a long distance to have to rapidly shift one's central vision, certainly much longer than the short distance - from the bowler's face to the window of release - that adherents to Chappell's theory have to shift their central vision. "It's ad hoc," says Chappell. He "could get there 75% of the time, but 25% of the time might struggle to get there at the right time, whereas… he could get [from the bowler's face to the window of release] nearly 100% of the time."

Watching the ball actually involves a certain amount of prediction about where the ball is going to be once released © Getty Images

They were also able to maintain their gaze at the point of bat-ball contact when hitting the ball. Hence, elite batsmen are more likely than club batsmen to be able to see their bat hitting the ball. Justin Langer, for example, told Mann, "I know that I watch the ball at the moment I hit it," and could clearly describe seeing markings on the ball as it made contact with his bat during his playing days. Don Bradman believed that this is possible too, instructing batsmen in his classic coaching book, The Art of Cricket: "Try to glue the eyes on the ball until the very moment it hits the bat. This cannot always be achieved in practice but try."

The superior ability to accurately perform the two saccades against balls of all lengths, Mann tells the Cricket Monthly, "seems to be non-negotiable" for elite batsmen. As a scientist, he is quick to acknowledge that "it's always hard to tease apart what makes [a batsman] great, or what's an effect of him being great", but underlines that "all the elite guys that we've tested" do the two saccades.

As a matter of logic, in order for the elite batsmen's saccadic eye movements to work successfully, they have to be able to accurately predict where the ball is going to be (so that they can saccade their vision to that spot before the ball gets there).

Think about that for a moment. Such an ability more closely resembles the powers of a (fictional) Jedi Knight than those we typically associate with real-world flesh-and-blood athletes. "He can see things before they happen," said the Jedi Master Qui-Gon Jinn of a nine-year-old boy named Anakin Skywalker. "That's why he appears to have such quick reflexes. It's a Jedi trait." Well, science now tells us that elite batsmen aren't much different: they know where the ball is going to be before it gets there and saccade their vision to that point. That's how they appear to have such quick reflexes.

That predictive ability is - as Chappell theorised 46 years ago in a Hobart hotel room - partially derived from the visual information batsmen obtain from a bowler's run-up and load-up. That information, explains Mann, is one of "three key sources of predictive information" for a batsman. The other two are the "online" information that a batsman can obtain from the live ball flight and the "contextual information" that a batsman can obtain about a bowler from having faced him before in a match, watching TV footage of him, or studying statistics about his prior behaviour.

The second strand of research lending support to Chappell's theory is a study conducted at the Australian Institute of Sport in 2010 by Mann, Abernethy and Damian Farrow. The scientists gave ten Australian grade batsmen with natural 20/20 vision contact lenses blurring their vision at three increasing levels: +1.00, +2.00 and +3.00. The batsmen - some of whom had represented their state or territory at senior or junior level - wore liquid crystal occlusion goggles that on random deliveries occluded (that is, completely blocked) their vision at the approximate moment when the bowler released the ball.

The scientists then tested the batsmen's performance against three bowlers - two medium-pacers who were opening the bowling in second grade in Canberra and a quick who had played in the Big Bash League as an opening bowler. The batsmen were asked to perform one of two tasks: try to strike the ball with their bat, or merely call out whether the ball was an off-side or leg-side delivery. The scientists then recorded whether the batsmen swung their bat on the correct side of the wicket, and whether they correctly called out off side or leg side.

The results they obtained were interesting. With their vision occluded when the bowler released the ball, the batsmen were able to swing their bat on the correct side of the wicket nearly 80% of the time when they were wearing +1.00 blurring lenses. This suggests that a batsman's ability to access the predictive clues in the bowler's run-up and load-up is arguably as, or even more, important to his ball-striking performance as his ability to actually see the ball at the moment it leaves the bowler's hand. (In case you were wondering, the +2.00 and +3.00 blurring lenses clearly reduced the batsmen's anticipatory performance.)

The batsmen's accuracy in calling out whether the ball was an off-side or leg-side delivery when they had 20/20 vision was terrible - barely above 50%. Their verbal calling performance clearly improved when they wore the +1.00 blurring lenses. This suggests that the batsmen's usage of the visual clues in the bowler's run-up and load-up is subconscious. "So when they were in the situation where they had to consciously think about [whether the ball would be a leg-side or off-side delivery] and… call out [which it would be], the +1.00 somehow made them better," says Mann. "It seems as though taking away that very clear, conscious information [that they get with 20/20 vision] may give them access to the [subconscious] information that they're more likely to rely on in a coupled scenario [that is, when they're asked to try hit the ball with their bat]."

Now, a sceptic might ask, scientific research in a laboratory is all well and good, but how does Chappell's theory fare today in the real world of first-class and Test cricket?

The Cricket Monthly spoke to six active professional Australian batsmen - all of whom have played Shield cricket and three of whom have played Test cricket - and one retired Australian Test batsman. Six of the seven batsmen - 27-year-old Chris Lynn, 35-year-old Ed Cowan, 24-year-old Kurtis Patterson, 20-year-old Will Pucovski, 46-year-old Greg Blewett, and 28-year-old Joe Burns - said that they naturally and independently developed a method for watching the ball that is either identical or very similar to Chappell's. The only one who didn't - 43-year-old Brad Hodge - had specific medical and environmental reasons for his divergence, as we will see.

Research suggests that even when their vision is obscured, batsmen can often correctly guess on which side the ball is going to land, based on clues they pick up from the bowler's run-up © Getty Images

Lynn, Cowan, Patterson, Pucovski and Blewett's methods are identical to Chappell's in that they do not watch the ball in the bowler's hand as he runs in to bowl and only start watching it when it appears in the window above and next to the bowler's head from where it will be released. Burns differs slightly in that he tries to visually "lock in" on the seam of the ball in the bowler's hand as soon as it comes up over the bowling shoulder just prior to release. Thus, he starts watching the ball a fraction earlier than the others and the window he looks at is larger than that used by the others, extending from the bowler's bowling shoulder all the way up to the estimated point of release.

This slight difference may stem from the fact that, unlike Lynn, Cowan, Patterson, Pucovski and Blewett, none of whom can recall ever using a method for watching the ball different from that which they use now, Burns clearly recalls using an entirely different method when he was a kid.

"I used to really focus on [the ball] in the bowler's hand [as he ran in]", says Burns, who has scored three Test hundreds in 13 Tests. One evening, when he was about 16, Burns felt "really rushed and hurried up by the ball" as he was batting under lights on a synthetic pitch while training at Northern Suburbs District Cricket Club in Brisbane's Shaw Park. The bowlers were getting faster, both in terms of ball- and arm speed, as he advanced through the ranks, and he realised there and then that watching the ball in the bowler's hand from the top of his mark just wasn't working. His reasoning was similar to that reached by Chappell and Blewett years earlier: his eyes were getting destabilised by the movement in the bowlers' hands as they ran in; he had insufficient time to react well to the ball being bowled; and there was a real risk that he could lose track of the ball, especially if the bowler had a whippy, slingy or heavily side-on action.

Thus, that evening in Shaw Park, Burns "naturally" switched to his present method. Like Chappell, Burns looks at the bowler - not the ball - as he runs in, keeping his eyes "relaxed", but whereas Chappell looked specifically at the bowler's face as he ran in, Burns looks at the bowler generally.

Blewett's point of focus is similar, although not identical to Burns'. He looks generally at the bowler's whole body as he's running in before focusing more on his top half as he gets closer to the crease. Lynn - an active coach who works with club mates and youngsters - and Patterson are identical to Chappell: they look at the bowler's face as he's running in. Cowan and Pucovski, a 20-year-old Victorian who has just scored his maiden first-class century in his second Shield game, do not consciously watch anything specific at all as the bowler's running in - Cowan refers to this almost meditative state of mind as "completely egoless and emotionless… indifference"; Pucovski calls it "trying to keep as clear a mind as possible" - but readily acknowledge that their subconscious is able to easily identify and process the visual predictive clues in the bowler's run-up and load-up.

"So much is picked up in those cues," observes Cowan, "and you can't underestimate" them, which is why, if he hasn't faced a bowler before, he will go watch them bowl from behind as they are warming up out in the middle and mentally "practise batting against them". That information is then safely stored in his mind, ready for his subconscious to access as the bowler runs in to bowl to him in the match. If a bowler runs in faster or grimaces, then that is picked up automatically by his subconscious mind without his conscious mind even realising it.

Similarly, despite not consciously watching anything specific at all as the bowler is running in, Pucovski has no trouble seeing predictive clues in the bowler's run-up and load-up, such as fast bowlers who "drag their front shoulder off" when they're about to bowl a bouncer, and bowlers who "open up their action quite a bit more" for their inswinger or are "more side-on" for their outswinger.

Even someone like Burns, who at a conscious level watches the bowler generally, says: "I don't think I consciously notice [those visual clues]. It's not like a bowler runs in and I think, 'Yeah, he's bowling an inswinger' or 'He's bowling an outswinger' or 'He's bowling a bumper'. But there are times where… it almost feels like instinct that you know where a ball is going to be. I think that's just from the cues that you pick up subconsciously from all the information that the bowler's giving you as he runs in." Lynn even looks at "where [the bowler's] eyes are looking" as he's running in.

The importance of conserving scarce mental energy was another of Chappell's principles that met with universal approval from the seven batsmen interviewed. Each had his own mechanism for completely switching off between balls and overs. Lynn relaxes his mind by standing still in his crease and having a look around the field, picking up any available cues from the fielders - especially the captain - and the bowler. Between overs, unless the match situation - for example, a pitch that's playing up or a run chase - requires it, Lynn generally doesn't think or talk about cricket at all. "Especially if I'm batting with someone like [Brendon] McCullum," says Lynn, "we just talk about whatever." He admits, with a good-natured laugh, that sometimes he and his batting partner will look into the crowd to "try and find" some attractive members of the other sex.

To switch off, Burns strolls down the pitch, does some gardening, chats to his partner then walks back to his crease. "If I stand stationary at the crease," he explains, "I start to have different thoughts in my mind, which just taxes energy from what I'm trying to do. So I try and keep myself active and not be still for too long."

A similar method is employed by Patterson, a tall, lean New South Welshman who, with 2250 first-class runs at 45.91 over the last two years, is knocking on the door to Test selection. "I just walk away to square leg and think about whatever it is that I want to think about and don't fight it," he explains. "I think it's important, particularly in longer-form cricket… to let your mind go [between balls]."

The colour-blind Brad Hodge preferred to watch the ball from the bowler's hand so he could focus on the seam © Getty Images

Blewett was the most flexible in terms of his mental relaxation routine between balls, being happy to choose one or more from a full menu of options: a chat with his partner, gardening, a walk out to square leg, a look into the crowd (to see family and friends) or the TV and radio commentary boxes (to see who was commentating). The one constant element in his routine was the final stage: he took his right-handed batting stance by putting his right foot down before his left foot.

Hodge ends his between-balls relaxation routine the exact same way. "I would never go in left foot first." But before stepping into his stance, Hodge employs a bucolic relaxation tactic that none of the other interviewed batsmen use: he walks away from the crease, puts his head down and looks at the grass for around 20 seconds, "because grass is a calming colour".

Most batsmen interviewed found the notion of watching the ball in the bowler's hand from the top of his mark - which, anecdotally, is how a significant proportion of club batsmen interpret the cliché "watch the ball" - to be utterly alien. Cowan, who played his 13th summer as a Shield cricketer and only today announced his retirement from first-class cricket, has "never heard of anyone" doing it at first-class level.

But there exists at least one who did (and still does in the BBL): Brad Hodge, who looks for the ball in the bowler's hand as he is walking back to his mark (to try to identify the shiny and rough sides), and when the bowler reaches the top of his mark, visually locates the seam of the ball in the hand, which, from that point on, becomes the object of the focus of his central vision.

Hodge is quick to point out that there are two peculiar reasons why he developed this method. Firstly, he's colour-blind. It's easier for him to pick up the ball if he focuses on the seam, which is clearly a different colour from the rest of the ball.

Hodge can't remember how he watched the ball when he was a kid, but he knows when he became conscious of the importance of watching the seam. It was the summer of 1993-94. He had just broken into Victoria's Shield team as an 18-year-old. One day early that summer, for the first - and, as it later turned out, only - time in his life, Hodge heard a fellow batsman speak about how to watch the ball. "Don't just watch the ball," said Dean Jones, "watch the seam of the ball." Those words commanded respect - Jones was not only Victoria's captain and best batsman, a veteran of 52 Tests and 150 ODIs with an average above 45 in both formats, but Hodge's childhood hero and mentor in the Victorian team.

The second reason why Hodge developed his method for watching the ball is peculiar not just to him but to all Victorian Shield batsmen: their home ground, the MCG, has a dry, abrasive pitch that is conducive to reverse swing. That reasoning is consistent with that of Blewett, Burns and Patterson, all of whom said that reverse swing constitutes an exception to their general rule of not watching the ball in the bowler's hand as he is running in. However, Blewett and Patterson add, this exception is rarely used nowadays because, as Patterson says, "most bowlers… like to cover the ball" as they are running in.

Hodge is in step with the other batsmen interviewed in that although his central vision is focused on the seam as the bowler is running in, he is "definitely" still able to pick up predictive clues in the bowler's run-up and load-up with his peripheral vision. Moreover, he observes that when he's in good form, his focus is "more broad", meaning that he's "not [consciously] looking for the seam" of the ball at all, "because, for some reason, his computer [that is, mind] will just do that naturally."

Lynn describes the state of being in good form in very similar terms: the ball "looks like it's coming down [in] slow motion and … it's like [your mind is] in auto-pilot. I've had games where I think 'F***, what happened there?' And you've done well and you can't really remember it because it's just on auto-pilot and it just does it itself basically."

All seven batsmen interviewed can see the seam of the ball and the shiny and rough sides as it travels towards them. Blewett, who batted in the top three for the bulk of his first-class and Test career, vividly recalls seeing "the gold writing" on the sides of new balls as they travelled towards him. When a spinner is bowling, all seven batsmen can see the ball spinning in the air as it travels towards them. Cowan points out that being able to see "how many revolutions" the ball has as it travels towards him is necessary for him to survive as a first-class batsman, because many spinners - for example, Fawad Ahmed - bowl with a scrambled seam, making it futile to watch the seam of the ball once they release it.

Even when the seam isn't scrambled, modern spinners bowl balls that are so well disguised that they can only be reliably picked by watching the rotations of the ball in the air. Fingerspinners, for example: Rangana Herath, R Ashwin and Steve O'Keefe, bowl a skidding straight ball that, for all intents and purposes, looks like their stock ball - identical seam position, almost identical bowling action - but is bowled with underspin rather than the overspin and/or sidespin that characterises their stock ball. Cowan picks that delivery - which, in Australia, is generally referred to as a "square ball" - by watching the ball spin backwards in the air as it travels towards him.

Bradman was unequivocal on this point. "A batsman," he wrote, "should be able to see the ball turning in the air as it comes down the pitch towards him when the bowler is a slow spinner. This is necessary against a class googly bowler like Arthur Mailey. Even if he disguises his googly you still have the added insurance of watching the spin of the ball to make sure which way it will turn on pitching."

This quality of vision is clearly the norm for batsmen at first-class and Test level, so much so that Blewett is genuinely taken aback when this writer - a bog-standard club cricketer - informs him that he has never been able to see the ball spinning in the air as it travels towards him. "That surprises me," he says in a politely bewildered tone, "because I just think that everyone's eyes are pretty similar and that you'd just be able to see that."

Most of the seven batsmen interviewed said that they could - in line with the scientific research conducted by Mann, Spratford, Abernethy and Sarpeshkar - recall seeing their bat hit the ball. "I know when I'm in form and whacking the ball, I'm watching the ball literally hit the base of the bat," says Lynn. The only two who could not recall seeing their bat hitting the ball were Blewett and Pucovski, but they could recall seeing it till late in its trajectory - roughly a metre before contact.

What does watching the ball mean exactly? It is a question most batsmen grapple with their entire careers © Getty Images

If a batsman has a well-honed method for watching the ball efficiently - like all Test and first-class batsmen do - then a substantial body of anecdotal evidence indicates that he will be able to see the ball well enough to smash it even if he doesn't have 20/20 eyesight. Bradman had less than 20/20 eyesight. Neil Harvey discovered early in his Test career that he was short-sighted and chose to keep playing without corrective lenses. Barry Richards made the same discovery much later in his career. He tried corrective lenses, but the 20/20 vision freaked him out - he saw too much. So he kept batting (successfully) without them.

More recently, Cowan only discovered that he was minus 1.50 short-sighted in his third year of university, when he sat at the back of some lecture theatres and struggled to see the whiteboard. He had been crowned the player of the national U-17s carnival, represented Australia in the U-19 World Cup, scored Sydney first-grade hundreds and broken into the NSW Shield squad while (unwittingly) being short-sighted enough to not be allowed to legally drive without corrective lenses. Even looking back on it now with 20/20 eyesight courtesy of laser surgery, Cowan says that he had no issues playing pace when he was short-sighted. The only thing that troubled him was playing spin, because he "couldn't really see the ball spin" in the air as it travelled towards him. "The joy of playing in Australia," he says with a chuckle, is that he just "assumed it wasn't going to turn".

Test and first-class batsmen naturally (and subconsciously) develop their methods of watching the ball efficiently by playing cricket against real bowlers from a young age. Interestingly, it appears that becoming aware of what exactly one's method is can dramatically improve a batsman's performance by allowing him to use that method more consistently. Chappell's epiphany in Hobart at the age of 23 is the most obvious example, but there are others.

In late March 2000, after playing 46 Tests over the preceding five years, 28-year-old Blewett was axed from the Australian Test team to make way for Matthew Hayden. Blewett went back to playing Shield cricket. Later that year, as he was batting in the nets at Adelaide Oval, South Australia's then coach, Greg Chappell, asked him, "Are you watching the ball closely?"

"Yeah, of course I am," replied Blewett.

"No, no," said Chappell, "are you really watching the ball out of the bowler's hand?"

Blewett went away and thought about it. For the first time in his life he became fully conscious of the fact that he had a precise method of watching the ball, just like Chappell had nearly three decades earlier. From that point on, Blewett stopped thinking about all the little technical things that he, like so many out-of-form batsmen, had been constantly tinkering with and said to himself: right, just watch the ball closely out of the window of release. "That," he recalls, "took out all my other thoughts and all I was doing was just watching the ball and reacting to the ball. Everything then just happened naturally for me, which was brilliant."

Armed with that self-awareness, Blewett embarked on the most productive period of his career, scoring 3055 first-class runs and ten hundreds, at an average of 57.64 over the next three Australian summers.

It is late December 1971. A tall, 23-year-old South Australian by the name of Greg Chappell walks down the ornate wood-and-iron staircase of Hadley's Orient Hotel in Hobart. He is meeting his older brother Ian for dinner. The two have been parachuted in to bolster a Tasmania Combined XI for their first-class match against a star-studded World XI featuring Sunil Gavaskar, Garry Sobers, Bishan Bedi and Zaheer Abbas at the Tasmania Cricket Association Ground.

The younger of the two Chappells follows the staircase as it takes a 90-degree left turn, walks past the large portrait of a young Queen Victoria and emerges into the beautiful red-and-gold carpeted lobby of the hotel built by convicts more than a century ago. Ian is running late, as usual. Greg, on time as usual, waits patiently. The concierge approaches him. "Mr Chappell," he says, "there's a letter for you." Greg immediately recognises the handwriting on the envelope - it belongs to his father.

He doesn't know it, but the contents of this envelope will change his life. There's no letter inside, just a newspaper clipping - an opinion article by the Adelaide Advertiser's chief cricket writer, Keith Butler. It says that Chappell is wasting his enormous talent and the way he's batting he won't make the forthcoming Ashes tour. At the end of the article he sees the one-line message his father has written: "I don't believe everything that Keith says, but it might be worth thinking about."

Suddenly, Greg doesn't feel hungry at all. "Mate," he tells Ian when he arrives in the lobby, "I'm just going to stay in." He walks back upstairs. He doesn't turn on the lights. In a corner of his single room, there is an upholstered chair. He sits down on it in the dark, alone, and thinks. He thinks about every single game of cricket that he has ever played, from his very first in the backyard with his brother Ian, to park and beach cricket with his mates, to schoolboys' cricket for Prince Alfred College, to grade cricket for Glenelg District Cricket Club, to Sheffield Shield cricket for South Australia, to county cricket for Somerset, to Test cricket for Australia.

What he seeks is nothing less than the answer to the question that has plagued every batsman since the dawn of time: what is the cause of the massive performance differential between my good days and my bad days? What exactly is it that I'm doing better on my good days than on my bad days?

As he searches his mind for the answer, he enters a deep meditative state. Time passes quickly. Hours later - it is difficult for him to tell how many - he emerges with a stunning realisation: by playing cricket since the age of four, he had, without realising it, developed a systemic process of concentration and a precise method of watching the ball; but he had only been using them consistently on his good days.

There lay the answer to his question: all he had to do was use his own systemic process of concentration and precise method of watching the ball every single time he walked out to bat.

From that day forth, he stops mindlessly hitting balls in training. Instead, he focuses on his process of concentration and method of watching the ball. The aim is to be able to use that mental routine against every single ball that he faces in a match. Five days after his epiphany in Hobart, he gets the opportunity to apply his newfound theory in a match. He is called up to play for Australia - captained by Ian - in their third unofficial Test against the Sobers-captained World XI at the MCG, starting on New Year's Day 1972.

In Australia's first innings, he scores an unbeaten 115. Eight days later, he scores an unbeaten 197 at the SCG in the fourth unofficial Test. As he walks off to the applause of the 19,125-strong crowd, he knows deep down that his batting has gone to an entirely different level. At the tender age of 23, he has discovered what most batsmen spend their entire careers searching fruitlessly for: the secret - for him, anyway - to scoring runs at Test level.

Before his epiphany in Hobart, Chappell scored 243 runs in five Tests at an average of 34.71. After his epiphany, he scored 6867 runs - including 23 hundreds - in 82 Tests at an average of 54.93.

The mental routine that enabled Chappell, in an era when Test bowling was arguably the strongest that it has ever been, to maintain a Test average in excess of 50 for nearly a decade is not particularly complicated.

It starts with the logical principle that mental energy is a finite resource that a batsman must conserve if he is to achieve his ultimate objective of scoring as many runs as possible, which will require him to spend hours, if not days, out in the middle.

Bradman had less than 20/20 eyesight. Barry Richards made the same discovery. He tried corrective lenses, but the 20/20 vision freaked him out - he saw too much

Chappell realised that he had three ascending levels of mental concentration: awareness, fine focus and fierce focus. In order to conserve his finite quantum of mental energy, he would have to use fierce focus as little as possible, so that it was always available when he really needed it. When he walked out to bat, his concentration would be set at its lowest, power-saving level: awareness. He would mark his guard and look around the field, methodically counting all ten fielders until his gaze reached the face of the bowler standing at the top of his mark.

At that point, he would increase his level of concentration to fine focus. As the bowler ran in, he would gently and rhythmically tap his bat on the ground, keeping his central vision on the bowler's face and his peripheral vision on the bowler's body. He believed that a bowler's facial expression and the bodily movements in his run-up and load-up offered the batsman valuable predictive clues as to what ball would be bowled. He would not look at the ball in the bowler's hand as he ran in.

As the bowler jumped into his delivery stride, he would switch up his concentration to its maximum level - fierce focus - and shift his central vision the short distance from the bowler's face to the window just above and next to his head from where he would release the ball. Once the ball appeared in that window, Chappell would watch the ball itself for the first time. He could see everything. He could see the seam of the ball and the shiny and rough side of the ball, even when he was facing a genuine fast bowler. Against spinners, he could see the ball spinning in the air as it travelled towards him. In the unlikely event that he failed to pick what delivery it was out of the hand, he could simply pick it in the air.

"There weren't too many balls that I faced that I was unsure about," Chappell tells the Cricket Monthly matter-of-factly. Because he was able to so quickly decipher where a ball was going to be, he was able to confidently move into position early to, if at all possible, play an attacking, run-scoring shot. Like all of Australia's great Test batsmen, Chappell believes that a batsman should always have the positive mindset of looking to score runs. The greatest threat to that mindset is, and has always been, the thought that lurks omnipresently in the back of every batsman's mind, simply because he is a human being: the fear of getting out. By giving the mind something to do at each and every stage of an innings, a well-defined mental routine such as Chappell's helps quash that fear.

As soon as he finished playing a delivery - whether he had driven it for four, left it, or played and missed it - Chappell cycled his concentration back down to its minimum level of awareness. He understood the importance of keeping his focus on the present. That meant that he had to completely let go of the last ball, even if it had missed his off stump by a millimetre. So he gave his mind something relaxing to do while it was powered down in awareness mode - he looked into the crowd and, whenever he was playing at home, he delighted in finding family and friends and seeing what they were up to. When they met up for dinner in the evenings, his friends were flabbergasted that he was able to recite their movements for the entire day.

Chappell realised that he had three ascending levels of mental concentration: awareness, fine focus and fierce focus. In order to conserve his finite quantum of mental energy, he would have to use fierce focus as little as possible, so that it was always available when he really needed it. When he walked out to bat, his concentration would be set at its lowest, power-saving level: awareness. He would mark his guard and look around the field, methodically counting all ten fielders until his gaze reached the face of the bowler standing at the top of his mark.

At that point, he would increase his level of concentration to fine focus. As the bowler ran in, he would gently and rhythmically tap his bat on the ground, keeping his central vision on the bowler's face and his peripheral vision on the bowler's body. He believed that a bowler's facial expression and the bodily movements in his run-up and load-up offered the batsman valuable predictive clues as to what ball would be bowled. He would not look at the ball in the bowler's hand as he ran in.

As the bowler jumped into his delivery stride, he would switch up his concentration to its maximum level - fierce focus - and shift his central vision the short distance from the bowler's face to the window just above and next to his head from where he would release the ball. Once the ball appeared in that window, Chappell would watch the ball itself for the first time. He could see everything. He could see the seam of the ball and the shiny and rough side of the ball, even when he was facing a genuine fast bowler. Against spinners, he could see the ball spinning in the air as it travelled towards him. In the unlikely event that he failed to pick what delivery it was out of the hand, he could simply pick it in the air.

"There weren't too many balls that I faced that I was unsure about," Chappell tells the Cricket Monthly matter-of-factly. Because he was able to so quickly decipher where a ball was going to be, he was able to confidently move into position early to, if at all possible, play an attacking, run-scoring shot. Like all of Australia's great Test batsmen, Chappell believes that a batsman should always have the positive mindset of looking to score runs. The greatest threat to that mindset is, and has always been, the thought that lurks omnipresently in the back of every batsman's mind, simply because he is a human being: the fear of getting out. By giving the mind something to do at each and every stage of an innings, a well-defined mental routine such as Chappell's helps quash that fear.

As soon as he finished playing a delivery - whether he had driven it for four, left it, or played and missed it - Chappell cycled his concentration back down to its minimum level of awareness. He understood the importance of keeping his focus on the present. That meant that he had to completely let go of the last ball, even if it had missed his off stump by a millimetre. So he gave his mind something relaxing to do while it was powered down in awareness mode - he looked into the crowd and, whenever he was playing at home, he delighted in finding family and friends and seeing what they were up to. When they met up for dinner in the evenings, his friends were flabbergasted that he was able to recite their movements for the entire day.

After his revelation in Hobart, Greg Chappell made more than 6500 runs at 54.93 © Getty Images

"I have no doubt," Chappell says, "that what allowed me to achieve what I achieved was the fact that I was lucky enough to have learned early in my career that it was about… my mind, not my body. And my subconscious mind was a better cricketer than I could ever be, so what I had to do was get the conscious mind out of the way… give it a job to do - watch his face, watch the [window of release] - and allow my subconscious mind to react to what came."

He saw that the mistake that most batsmen make, especially when they are striving to fulfil their lifelong dream of playing Test cricket for their country, is that they try too hard. They stop trusting the natural instincts that have got them that far and start worrying about getting out, or fretting about the correctness or otherwise of their technique.

At club level, the mistake of trying too hard manifests itself in an even more fundamental error - watching the ball too hard. Former Australia batsman Greg Blewett vividly recalls playing against some grade batsmen who never took their eyes off the ball while they were on strike. They would "watch the ball go from the keeper's hands to first slip, from first slip to point, point to cover, cover to mid-off [and mid-off to the bowler's hands]". Then they would keep watching the ball in the bowler's hands from the top of his run-up to the point of release.

According to Chappell's theory, that method of narrowly watching the ball creates at least four substantive problems.

Firstly, the batsman burns through his finite quantum of mental energy at a rapid rate.

Secondly, watching the ball in the bowler's hand as he is running in has the potential to destabilise a batsman's eyes. "Some bowlers run in and their arms are going everywhere," explains Blewett, a follower of Chappell's theory in the back end of his playing career and now an advocate of it as the head coach of South Australia Under-19s and an assistant coach of South Australia and Adelaide Strikers. "It'd be really hard to focus on that ball [because] your eyes would be darting all over the place."

Thirdly, if the batsman watches the ball in the bowler's hand as he's running in then once the bowler jumps into his delivery stride, he will have to quickly shift his central vision from the ball in the bowler's hand next to his thigh up to the area above his head from which he will release the ball. That is a long distance to have to rapidly shift one's central vision, certainly much longer than the short distance - from the bowler's face to the window of release - that adherents to Chappell's theory have to shift their central vision. "It's ad hoc," says Chappell. He "could get there 75% of the time, but 25% of the time might struggle to get there at the right time, whereas… he could get [from the bowler's face to the window of release] nearly 100% of the time."

Greg Blewett firmly believes that the subject of watching the ball and how to best watch it is "one of the most important things there is" for batsmen

Fourthly, if the batsman focuses his gaze solely and exclusively on the ball in the bowler's hand as he is running in, then he undermines his peripheral vision of the bowler's face and body, thereby robbing himself of the visual clues that may help him predict what ball the bowler is going to bowl.

Thus, "watch the ball", that generic bit of advice that every cricketer has heard at some point in their life, could, says Chappell, "be the wrong instruction" - if it is unaccompanied by any explanation or discussion as to how to watch the ball.

Indeed, one could argue that the batting maxim reportedly promulgated by the current Australian head coach Darren Lehmann - "watch the ball, c**t" - is problematic for more reasons than one. It could easily be misinterpreted to mean "watch the ball really hard", which would lead batsmen to watch the ball in an overly narrow fashion.

When Chappell first became aware of his method of watching the ball some 46 years ago, the technology did not exist to scientifically test and evaluate it. That technology - in the form of glasses that allow scientists to record and see where a batsman is looking - now exists, and in the past seven years two strands of research have emerged to support Chappell's method.

The first strand consists of two empirical studies. The first of those studies, conducted by sports scientists David Mann, Wayne Spratford and Bruce Abernethy in 2012, tested the batting performance of two Australian Test batsmen - each of whom had played more than 70 Tests and averaged in excess of 45 - and two Australian grade batsmen. This was done with the players wearing Mobile Eye eye-tracking glasses. The second study, conducted by sports scientists Abernethy, Mann and Vishnu Sarpeshkar in 2017, tested the batting performance of 43 batsmen while they wore the same glasses - 13 elite adults who had represented their state or country at senior level (including four members of the Australian squad), ten elite juniors who had represented their state or country at U-19 or U-17 level (including four members of the Australian U-19 squad), ten adult club batsmen (with an average age of 31.7) and ten young club batsmen (with an average age of 21).

A key finding from these two empirical studies is that the elite batsmen - that is, the two Australian Test batsmen from the 2012 study and the 13 elite adults and ten elite juniors from the 2017 study - were distinguished from club batsmen by their superior ability to predictively saccade their vision: that is, they could accurately jump their vision ahead of the ball's live flight path to where the ball is going to be.

When they were facing anything shorter than a full delivery, the elite batsmen were generally able to accurately saccade their vision twice - once to the point of bounce, and once following the point of bounce to the point of bat-ball impact.

Fourthly, if the batsman focuses his gaze solely and exclusively on the ball in the bowler's hand as he is running in, then he undermines his peripheral vision of the bowler's face and body, thereby robbing himself of the visual clues that may help him predict what ball the bowler is going to bowl.

Thus, "watch the ball", that generic bit of advice that every cricketer has heard at some point in their life, could, says Chappell, "be the wrong instruction" - if it is unaccompanied by any explanation or discussion as to how to watch the ball.

Indeed, one could argue that the batting maxim reportedly promulgated by the current Australian head coach Darren Lehmann - "watch the ball, c**t" - is problematic for more reasons than one. It could easily be misinterpreted to mean "watch the ball really hard", which would lead batsmen to watch the ball in an overly narrow fashion.

When Chappell first became aware of his method of watching the ball some 46 years ago, the technology did not exist to scientifically test and evaluate it. That technology - in the form of glasses that allow scientists to record and see where a batsman is looking - now exists, and in the past seven years two strands of research have emerged to support Chappell's method.

The first strand consists of two empirical studies. The first of those studies, conducted by sports scientists David Mann, Wayne Spratford and Bruce Abernethy in 2012, tested the batting performance of two Australian Test batsmen - each of whom had played more than 70 Tests and averaged in excess of 45 - and two Australian grade batsmen. This was done with the players wearing Mobile Eye eye-tracking glasses. The second study, conducted by sports scientists Abernethy, Mann and Vishnu Sarpeshkar in 2017, tested the batting performance of 43 batsmen while they wore the same glasses - 13 elite adults who had represented their state or country at senior level (including four members of the Australian squad), ten elite juniors who had represented their state or country at U-19 or U-17 level (including four members of the Australian U-19 squad), ten adult club batsmen (with an average age of 31.7) and ten young club batsmen (with an average age of 21).

A key finding from these two empirical studies is that the elite batsmen - that is, the two Australian Test batsmen from the 2012 study and the 13 elite adults and ten elite juniors from the 2017 study - were distinguished from club batsmen by their superior ability to predictively saccade their vision: that is, they could accurately jump their vision ahead of the ball's live flight path to where the ball is going to be.

When they were facing anything shorter than a full delivery, the elite batsmen were generally able to accurately saccade their vision twice - once to the point of bounce, and once following the point of bounce to the point of bat-ball impact.

Watching the ball actually involves a certain amount of prediction about where the ball is going to be once released © Getty Images

They were also able to maintain their gaze at the point of bat-ball contact when hitting the ball. Hence, elite batsmen are more likely than club batsmen to be able to see their bat hitting the ball. Justin Langer, for example, told Mann, "I know that I watch the ball at the moment I hit it," and could clearly describe seeing markings on the ball as it made contact with his bat during his playing days. Don Bradman believed that this is possible too, instructing batsmen in his classic coaching book, The Art of Cricket: "Try to glue the eyes on the ball until the very moment it hits the bat. This cannot always be achieved in practice but try."

The superior ability to accurately perform the two saccades against balls of all lengths, Mann tells the Cricket Monthly, "seems to be non-negotiable" for elite batsmen. As a scientist, he is quick to acknowledge that "it's always hard to tease apart what makes [a batsman] great, or what's an effect of him being great", but underlines that "all the elite guys that we've tested" do the two saccades.

As a matter of logic, in order for the elite batsmen's saccadic eye movements to work successfully, they have to be able to accurately predict where the ball is going to be (so that they can saccade their vision to that spot before the ball gets there).

Think about that for a moment. Such an ability more closely resembles the powers of a (fictional) Jedi Knight than those we typically associate with real-world flesh-and-blood athletes. "He can see things before they happen," said the Jedi Master Qui-Gon Jinn of a nine-year-old boy named Anakin Skywalker. "That's why he appears to have such quick reflexes. It's a Jedi trait." Well, science now tells us that elite batsmen aren't much different: they know where the ball is going to be before it gets there and saccade their vision to that point. That's how they appear to have such quick reflexes.

That predictive ability is - as Chappell theorised 46 years ago in a Hobart hotel room - partially derived from the visual information batsmen obtain from a bowler's run-up and load-up. That information, explains Mann, is one of "three key sources of predictive information" for a batsman. The other two are the "online" information that a batsman can obtain from the live ball flight and the "contextual information" that a batsman can obtain about a bowler from having faced him before in a match, watching TV footage of him, or studying statistics about his prior behaviour.

The second strand of research lending support to Chappell's theory is a study conducted at the Australian Institute of Sport in 2010 by Mann, Abernethy and Damian Farrow. The scientists gave ten Australian grade batsmen with natural 20/20 vision contact lenses blurring their vision at three increasing levels: +1.00, +2.00 and +3.00. The batsmen - some of whom had represented their state or territory at senior or junior level - wore liquid crystal occlusion goggles that on random deliveries occluded (that is, completely blocked) their vision at the approximate moment when the bowler released the ball.

What Chappell seeks is nothing less than the answer to the question that has plagued every batsman: what is the cause of the massive differential between my good days and bad?

The scientists then tested the batsmen's performance against three bowlers - two medium-pacers who were opening the bowling in second grade in Canberra and a quick who had played in the Big Bash League as an opening bowler. The batsmen were asked to perform one of two tasks: try to strike the ball with their bat, or merely call out whether the ball was an off-side or leg-side delivery. The scientists then recorded whether the batsmen swung their bat on the correct side of the wicket, and whether they correctly called out off side or leg side.

The results they obtained were interesting. With their vision occluded when the bowler released the ball, the batsmen were able to swing their bat on the correct side of the wicket nearly 80% of the time when they were wearing +1.00 blurring lenses. This suggests that a batsman's ability to access the predictive clues in the bowler's run-up and load-up is arguably as, or even more, important to his ball-striking performance as his ability to actually see the ball at the moment it leaves the bowler's hand. (In case you were wondering, the +2.00 and +3.00 blurring lenses clearly reduced the batsmen's anticipatory performance.)

The batsmen's accuracy in calling out whether the ball was an off-side or leg-side delivery when they had 20/20 vision was terrible - barely above 50%. Their verbal calling performance clearly improved when they wore the +1.00 blurring lenses. This suggests that the batsmen's usage of the visual clues in the bowler's run-up and load-up is subconscious. "So when they were in the situation where they had to consciously think about [whether the ball would be a leg-side or off-side delivery] and… call out [which it would be], the +1.00 somehow made them better," says Mann. "It seems as though taking away that very clear, conscious information [that they get with 20/20 vision] may give them access to the [subconscious] information that they're more likely to rely on in a coupled scenario [that is, when they're asked to try hit the ball with their bat]."

Now, a sceptic might ask, scientific research in a laboratory is all well and good, but how does Chappell's theory fare today in the real world of first-class and Test cricket?

The Cricket Monthly spoke to six active professional Australian batsmen - all of whom have played Shield cricket and three of whom have played Test cricket - and one retired Australian Test batsman. Six of the seven batsmen - 27-year-old Chris Lynn, 35-year-old Ed Cowan, 24-year-old Kurtis Patterson, 20-year-old Will Pucovski, 46-year-old Greg Blewett, and 28-year-old Joe Burns - said that they naturally and independently developed a method for watching the ball that is either identical or very similar to Chappell's. The only one who didn't - 43-year-old Brad Hodge - had specific medical and environmental reasons for his divergence, as we will see.

Research suggests that even when their vision is obscured, batsmen can often correctly guess on which side the ball is going to land, based on clues they pick up from the bowler's run-up © Getty Images

Lynn, Cowan, Patterson, Pucovski and Blewett's methods are identical to Chappell's in that they do not watch the ball in the bowler's hand as he runs in to bowl and only start watching it when it appears in the window above and next to the bowler's head from where it will be released. Burns differs slightly in that he tries to visually "lock in" on the seam of the ball in the bowler's hand as soon as it comes up over the bowling shoulder just prior to release. Thus, he starts watching the ball a fraction earlier than the others and the window he looks at is larger than that used by the others, extending from the bowler's bowling shoulder all the way up to the estimated point of release.

This slight difference may stem from the fact that, unlike Lynn, Cowan, Patterson, Pucovski and Blewett, none of whom can recall ever using a method for watching the ball different from that which they use now, Burns clearly recalls using an entirely different method when he was a kid.

"I used to really focus on [the ball] in the bowler's hand [as he ran in]", says Burns, who has scored three Test hundreds in 13 Tests. One evening, when he was about 16, Burns felt "really rushed and hurried up by the ball" as he was batting under lights on a synthetic pitch while training at Northern Suburbs District Cricket Club in Brisbane's Shaw Park. The bowlers were getting faster, both in terms of ball- and arm speed, as he advanced through the ranks, and he realised there and then that watching the ball in the bowler's hand from the top of his mark just wasn't working. His reasoning was similar to that reached by Chappell and Blewett years earlier: his eyes were getting destabilised by the movement in the bowlers' hands as they ran in; he had insufficient time to react well to the ball being bowled; and there was a real risk that he could lose track of the ball, especially if the bowler had a whippy, slingy or heavily side-on action.

Thus, that evening in Shaw Park, Burns "naturally" switched to his present method. Like Chappell, Burns looks at the bowler - not the ball - as he runs in, keeping his eyes "relaxed", but whereas Chappell looked specifically at the bowler's face as he ran in, Burns looks at the bowler generally.

Blewett's point of focus is similar, although not identical to Burns'. He looks generally at the bowler's whole body as he's running in before focusing more on his top half as he gets closer to the crease. Lynn - an active coach who works with club mates and youngsters - and Patterson are identical to Chappell: they look at the bowler's face as he's running in. Cowan and Pucovski, a 20-year-old Victorian who has just scored his maiden first-class century in his second Shield game, do not consciously watch anything specific at all as the bowler's running in - Cowan refers to this almost meditative state of mind as "completely egoless and emotionless… indifference"; Pucovski calls it "trying to keep as clear a mind as possible" - but readily acknowledge that their subconscious is able to easily identify and process the visual predictive clues in the bowler's run-up and load-up.

Cowan does not consciously watch anything specific as the bowler is running in - he refers to this almost meditative state of mind as "completely egoless and emotionless… indifference"

"So much is picked up in those cues," observes Cowan, "and you can't underestimate" them, which is why, if he hasn't faced a bowler before, he will go watch them bowl from behind as they are warming up out in the middle and mentally "practise batting against them". That information is then safely stored in his mind, ready for his subconscious to access as the bowler runs in to bowl to him in the match. If a bowler runs in faster or grimaces, then that is picked up automatically by his subconscious mind without his conscious mind even realising it.

Similarly, despite not consciously watching anything specific at all as the bowler is running in, Pucovski has no trouble seeing predictive clues in the bowler's run-up and load-up, such as fast bowlers who "drag their front shoulder off" when they're about to bowl a bouncer, and bowlers who "open up their action quite a bit more" for their inswinger or are "more side-on" for their outswinger.

Even someone like Burns, who at a conscious level watches the bowler generally, says: "I don't think I consciously notice [those visual clues]. It's not like a bowler runs in and I think, 'Yeah, he's bowling an inswinger' or 'He's bowling an outswinger' or 'He's bowling a bumper'. But there are times where… it almost feels like instinct that you know where a ball is going to be. I think that's just from the cues that you pick up subconsciously from all the information that the bowler's giving you as he runs in." Lynn even looks at "where [the bowler's] eyes are looking" as he's running in.

The importance of conserving scarce mental energy was another of Chappell's principles that met with universal approval from the seven batsmen interviewed. Each had his own mechanism for completely switching off between balls and overs. Lynn relaxes his mind by standing still in his crease and having a look around the field, picking up any available cues from the fielders - especially the captain - and the bowler. Between overs, unless the match situation - for example, a pitch that's playing up or a run chase - requires it, Lynn generally doesn't think or talk about cricket at all. "Especially if I'm batting with someone like [Brendon] McCullum," says Lynn, "we just talk about whatever." He admits, with a good-natured laugh, that sometimes he and his batting partner will look into the crowd to "try and find" some attractive members of the other sex.

To switch off, Burns strolls down the pitch, does some gardening, chats to his partner then walks back to his crease. "If I stand stationary at the crease," he explains, "I start to have different thoughts in my mind, which just taxes energy from what I'm trying to do. So I try and keep myself active and not be still for too long."

A similar method is employed by Patterson, a tall, lean New South Welshman who, with 2250 first-class runs at 45.91 over the last two years, is knocking on the door to Test selection. "I just walk away to square leg and think about whatever it is that I want to think about and don't fight it," he explains. "I think it's important, particularly in longer-form cricket… to let your mind go [between balls]."

The colour-blind Brad Hodge preferred to watch the ball from the bowler's hand so he could focus on the seam © Getty Images

Blewett was the most flexible in terms of his mental relaxation routine between balls, being happy to choose one or more from a full menu of options: a chat with his partner, gardening, a walk out to square leg, a look into the crowd (to see family and friends) or the TV and radio commentary boxes (to see who was commentating). The one constant element in his routine was the final stage: he took his right-handed batting stance by putting his right foot down before his left foot.

Hodge ends his between-balls relaxation routine the exact same way. "I would never go in left foot first." But before stepping into his stance, Hodge employs a bucolic relaxation tactic that none of the other interviewed batsmen use: he walks away from the crease, puts his head down and looks at the grass for around 20 seconds, "because grass is a calming colour".

Most batsmen interviewed found the notion of watching the ball in the bowler's hand from the top of his mark - which, anecdotally, is how a significant proportion of club batsmen interpret the cliché "watch the ball" - to be utterly alien. Cowan, who played his 13th summer as a Shield cricketer and only today announced his retirement from first-class cricket, has "never heard of anyone" doing it at first-class level.

But there exists at least one who did (and still does in the BBL): Brad Hodge, who looks for the ball in the bowler's hand as he is walking back to his mark (to try to identify the shiny and rough sides), and when the bowler reaches the top of his mark, visually locates the seam of the ball in the hand, which, from that point on, becomes the object of the focus of his central vision.

Hodge is quick to point out that there are two peculiar reasons why he developed this method. Firstly, he's colour-blind. It's easier for him to pick up the ball if he focuses on the seam, which is clearly a different colour from the rest of the ball.

Hodge can't remember how he watched the ball when he was a kid, but he knows when he became conscious of the importance of watching the seam. It was the summer of 1993-94. He had just broken into Victoria's Shield team as an 18-year-old. One day early that summer, for the first - and, as it later turned out, only - time in his life, Hodge heard a fellow batsman speak about how to watch the ball. "Don't just watch the ball," said Dean Jones, "watch the seam of the ball." Those words commanded respect - Jones was not only Victoria's captain and best batsman, a veteran of 52 Tests and 150 ODIs with an average above 45 in both formats, but Hodge's childhood hero and mentor in the Victorian team.

The second reason why Hodge developed his method for watching the ball is peculiar not just to him but to all Victorian Shield batsmen: their home ground, the MCG, has a dry, abrasive pitch that is conducive to reverse swing. That reasoning is consistent with that of Blewett, Burns and Patterson, all of whom said that reverse swing constitutes an exception to their general rule of not watching the ball in the bowler's hand as he is running in. However, Blewett and Patterson add, this exception is rarely used nowadays because, as Patterson says, "most bowlers… like to cover the ball" as they are running in.

"I know when I'm in form and whacking the ball, I'm watching the ball literally hit the base of the bat" CHRIS LYNN

Hodge is in step with the other batsmen interviewed in that although his central vision is focused on the seam as the bowler is running in, he is "definitely" still able to pick up predictive clues in the bowler's run-up and load-up with his peripheral vision. Moreover, he observes that when he's in good form, his focus is "more broad", meaning that he's "not [consciously] looking for the seam" of the ball at all, "because, for some reason, his computer [that is, mind] will just do that naturally."

Lynn describes the state of being in good form in very similar terms: the ball "looks like it's coming down [in] slow motion and … it's like [your mind is] in auto-pilot. I've had games where I think 'F***, what happened there?' And you've done well and you can't really remember it because it's just on auto-pilot and it just does it itself basically."

All seven batsmen interviewed can see the seam of the ball and the shiny and rough sides as it travels towards them. Blewett, who batted in the top three for the bulk of his first-class and Test career, vividly recalls seeing "the gold writing" on the sides of new balls as they travelled towards him. When a spinner is bowling, all seven batsmen can see the ball spinning in the air as it travels towards them. Cowan points out that being able to see "how many revolutions" the ball has as it travels towards him is necessary for him to survive as a first-class batsman, because many spinners - for example, Fawad Ahmed - bowl with a scrambled seam, making it futile to watch the seam of the ball once they release it.

Even when the seam isn't scrambled, modern spinners bowl balls that are so well disguised that they can only be reliably picked by watching the rotations of the ball in the air. Fingerspinners, for example: Rangana Herath, R Ashwin and Steve O'Keefe, bowl a skidding straight ball that, for all intents and purposes, looks like their stock ball - identical seam position, almost identical bowling action - but is bowled with underspin rather than the overspin and/or sidespin that characterises their stock ball. Cowan picks that delivery - which, in Australia, is generally referred to as a "square ball" - by watching the ball spin backwards in the air as it travels towards him.

Bradman was unequivocal on this point. "A batsman," he wrote, "should be able to see the ball turning in the air as it comes down the pitch towards him when the bowler is a slow spinner. This is necessary against a class googly bowler like Arthur Mailey. Even if he disguises his googly you still have the added insurance of watching the spin of the ball to make sure which way it will turn on pitching."

This quality of vision is clearly the norm for batsmen at first-class and Test level, so much so that Blewett is genuinely taken aback when this writer - a bog-standard club cricketer - informs him that he has never been able to see the ball spinning in the air as it travels towards him. "That surprises me," he says in a politely bewildered tone, "because I just think that everyone's eyes are pretty similar and that you'd just be able to see that."

Most of the seven batsmen interviewed said that they could - in line with the scientific research conducted by Mann, Spratford, Abernethy and Sarpeshkar - recall seeing their bat hit the ball. "I know when I'm in form and whacking the ball, I'm watching the ball literally hit the base of the bat," says Lynn. The only two who could not recall seeing their bat hitting the ball were Blewett and Pucovski, but they could recall seeing it till late in its trajectory - roughly a metre before contact.

What does watching the ball mean exactly? It is a question most batsmen grapple with their entire careers © Getty Images

If a batsman has a well-honed method for watching the ball efficiently - like all Test and first-class batsmen do - then a substantial body of anecdotal evidence indicates that he will be able to see the ball well enough to smash it even if he doesn't have 20/20 eyesight. Bradman had less than 20/20 eyesight. Neil Harvey discovered early in his Test career that he was short-sighted and chose to keep playing without corrective lenses. Barry Richards made the same discovery much later in his career. He tried corrective lenses, but the 20/20 vision freaked him out - he saw too much. So he kept batting (successfully) without them.

More recently, Cowan only discovered that he was minus 1.50 short-sighted in his third year of university, when he sat at the back of some lecture theatres and struggled to see the whiteboard. He had been crowned the player of the national U-17s carnival, represented Australia in the U-19 World Cup, scored Sydney first-grade hundreds and broken into the NSW Shield squad while (unwittingly) being short-sighted enough to not be allowed to legally drive without corrective lenses. Even looking back on it now with 20/20 eyesight courtesy of laser surgery, Cowan says that he had no issues playing pace when he was short-sighted. The only thing that troubled him was playing spin, because he "couldn't really see the ball spin" in the air as it travelled towards him. "The joy of playing in Australia," he says with a chuckle, is that he just "assumed it wasn't going to turn".

Test and first-class batsmen naturally (and subconsciously) develop their methods of watching the ball efficiently by playing cricket against real bowlers from a young age. Interestingly, it appears that becoming aware of what exactly one's method is can dramatically improve a batsman's performance by allowing him to use that method more consistently. Chappell's epiphany in Hobart at the age of 23 is the most obvious example, but there are others.

In late March 2000, after playing 46 Tests over the preceding five years, 28-year-old Blewett was axed from the Australian Test team to make way for Matthew Hayden. Blewett went back to playing Shield cricket. Later that year, as he was batting in the nets at Adelaide Oval, South Australia's then coach, Greg Chappell, asked him, "Are you watching the ball closely?"

"Yeah, of course I am," replied Blewett.

"No, no," said Chappell, "are you really watching the ball out of the bowler's hand?"

Blewett went away and thought about it. For the first time in his life he became fully conscious of the fact that he had a precise method of watching the ball, just like Chappell had nearly three decades earlier. From that point on, Blewett stopped thinking about all the little technical things that he, like so many out-of-form batsmen, had been constantly tinkering with and said to himself: right, just watch the ball closely out of the window of release. "That," he recalls, "took out all my other thoughts and all I was doing was just watching the ball and reacting to the ball. Everything then just happened naturally for me, which was brilliant."

Armed with that self-awareness, Blewett embarked on the most productive period of his career, scoring 3055 first-class runs and ten hundreds, at an average of 57.64 over the next three Australian summers.