'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label spin. Show all posts

Showing posts with label spin. Show all posts

Saturday, 19 February 2022

Monday, 6 December 2021

Looks fast, feels faster - why the speed gun is only part of the story

Data on release points and trajectory are helping to break down the mysteries of why some bowlers are harder to face than others writes Cameron Ponsonby in Cricinfo

Shubman Gill ducks a Pat Cummins bouncer during India's Test tour of Australia in 2020-21 AFP/Getty Images

South Africa's Andrew Hall is on strike against Brett Lee at the Wanderers stadium in Johannesburg. The ball is bowled and Hall tucks it into the leg side before setting off for a gentle single.

As he jogs to the other end he hears a belated cheer from the crowd. Confused, he looks around to see the big screen displaying an announcement. He has just faced the fastest ball ever to have been bowled at the Wanderers.

Still confused, Hall's eyes move from the screen to Lee and they trade a quizzical look: "There's no way that was that quick."

The next ball, Lee runs in and bowls a bouncer to Gary Kirsten that flies past his face. Lee and Hall catch each other's eye once more,

"That one was."

You see, the speed gun is the movie adaptation of your favourite book. Yes, it tells the story. But it doesn't tell the full one.

****

"A lot of what makes Test players special happens before the ball comes out of a bowler's hand."

Those are the words of England analyst Nathan Leamon, speaking on Jarrod Kimber's Red Inker podcast. As a starting point, it shines a light on one of the limitations of the speed gun. It only tells us how fast a ball is at the point of release and tells us nothing about what has happened before or what happens after.

And what happens before is crucial. It is very easy to think of facing fast bowling as primarily a reactive skill. In fact, read any article on quick bowling and it will invariably say you only have 0.4 seconds to react to a 90mph delivery.

But what does that mean? No one can compute information in 0.4 seconds. It's beyond our realm of thinking in the same way that looking out of an aeroplane window doesn't give you vertigo because you're simply too high up for your brain to process it.

However, the reason it's possible is because, whilst you may only have 0.4 seconds to react, you have a lot longer than that to plan. And the best in the world plan exceptionally well.

Hall describes a training method that South Africa would use in order to be able to associate a bowler's release point with length. After a ball was bowled, they'd walk down the wicket and place a cone or mark a spot with their bat where they believed the ball had landed. The coach would confirm it or correct what the player thought.

The idea is in essence basic trigonometry. Over time, you learn to associate that if a bowler releases the ball with his arm at 12 o'clock, the delivery would be full. If he releases the ball at 1 o'clock, it would be short. It's a process designed to consciously train the subconscious, and Jacques Kallis was the best at it.

"Whether he played and missed," Hall says, "or left it, or ducked out the way, he'd be able to come down the track and isolate a rough area of where that ball had landed. And the reason he was so good at it is he became really sharp at picking up length and he made some bowlers look slower because of that. Because as they let go of the ball, he knew within a couple of inches where it was going to land."

Jasprit Bumrah roars after having Joe Root caught in the slips AFP/Getty Images

Jasprit Bumrah roars after having Joe Root caught in the slips AFP/Getty Images

There are a number of pre-delivery cues that Hall, as an international player, would be looking out for. Some were obvious tells, such as a bowler running in that bit harder before bowling a bouncer; others more subtle, like a bowler's head falling away in their action so they were able to push the ball into the batter and bowl an inswinger.

These cues weren't restricted to fast bowlers either. When talking about how to face Muthiah Muralidaran, Hall explains that one of the cues the South Africans would look out for was where his right elbow would be pointing as he entered his delivery stride. If it was pointing out at 90 degrees with his hand by his ear lobe, that was the sign that Muralitharan was going to bowl his off-spinner. If his elbow was pointing down towards the batter, it was probably a doosra coming up.

"You still wouldn't be able to play it half the time," Hall adds, "but you had an idea."

And some bowlers give you more of these cues than others, meaning a bowler at 87mph may feel quicker than one at 90mph if they give the batter fewer clues in their action.

Mark Ramprakash spoke of this when comparing his experience of facing Lee and Jason Gillespie in the 2001 Ashes. Lee was the faster bowler of the two, but his textbook action, with the ball always in sight, meant that Ramprakash felt he could consistently time his pre-delivery movement. But when he faced Gillespie, despite his being slower on the speed gun, it felt quicker. And this was because Gillespie would appear almost to release the ball before he'd really landed on the ground, throwing off Ramprakash's timings. When facing Lee, Ramprakash was planning. But when he was facing Gillespie, he was reacting.

In simple terms, there's a correlation between a bowler being "different" and the feeling that they are faster than they actually are. Batters are brought up on a diet of right-arm-over bowling that is released from nigh-on the same area, ball after ball after ball. Remove that familiarity, and the feeling of speed goes up.

In the Caribbean in 2019, TV showed Jasprit Bumrah's release point was half a metre closer to the batter than Kemar Roach's. This gave Bumrah the effect of bowling 3.7mph faster than the speed gun was showing

"Take Lasith Malinga," Hall says. "If you've not faced him before, you're literally going 'what am I supposed to watch?' But you soon get told, when he gets into his action, to watch the umpire's chest and neck. If you're watching his arm, you're struggling. And that's why in the beginning he'd clean people up and they'd say 'ah, he's quick'. He's not that quick. You just couldn't follow the ball."

****

Another quirk of how we consider pace is that by measuring the speed at which a ball is released, we're not actually measuring how long it takes to reach the batter. And there's a difference.

For instance, if you set up a bowling machine at 85mph and deliver three balls in a row, one of which is a full toss, the second a good length delivery and the third a bouncer, each of the three balls will reach the other end in a different amount of time because when the ball hits the pitch, it slows down. And the steeper that impact is, the more it will slow. So counterintuitively, the bouncer, cricket's scariest delivery, is actually the slowest of the three, whereas the full toss, cricket's worst delivery, is the fastest.

But what we don't know is how different bowlers compare to each other in terms of how much pace they lose off the wicket. The information is out there, but it's just not readily available. Angus Reid from VirtualEye - the company that provides ball-tracking data for Test matches in Australia - recalls how, during Naseem Shah's Test debut for Pakistan, they did a piece for broadcast comparing how he and Australia's Pat Cummins were releasing the ball at very similar speeds, but Shah was reaching the batter faster due to a combination of his height, ball trajectory and "skiddy" nature.

Steven Smith was pinned by a Jofra Archer bouncer at Lord's in 2019 Getty Images

Steven Smith was pinned by a Jofra Archer bouncer at Lord's in 2019 Getty Images

And we know from player anecdotes that these things matter. Hall explains how bowlers will sometimes bowl their bouncer with a cross-seam in the hope that the ball lands on the lacquer and loses less pace when it pitches. It is the same notion that Joe Root expressed earlier this year when he said India's spinner Axar Patel was beating England for pace in the pink-ball Test at Ahmedabad, because the skid off the lacquer gave the feeling that the ball was "gathering pace" off the wicket.

Conversely, many bowlers are said to bowl a "heavy ball", whereby batters feel that the ball is "hitting the bat harder" than expected. One such bowler was New Zealand bowler Iain O'Brien, who believes this was a consequence of the ball kicking up off the pitch and striking the blade higher than anticipated, due to more backspin being imparted upon release. Such was the backspin that Andrew Flintoff imparted on the ball, in the lead up to the 2005 Ashes he was accused of chucking as his wrist would snap so dramatically at the point of delivery.

This is one of the difficulties of trying to express the feeling of speed to a wider audience. For the spectator, it's merely a number because we have no other frame of reference. But for the batter, it's an experience. A moment in time that is almost over before it's begun.

One former international cricketer laughed when asked whether he would check the speed gun after facing a delivery. "Why would I need the speed gun to tell me if a ball was fast? I was the one who just faced it."

****

The final piece of the puzzle concerns the ball's release point.

When India were touring the Caribbean in 2019, TV showed an overlay of Jasprit Bumrah's release point compared to Kemar Roach's, demonstrating that Bumrah was bowling the ball half a metre closer to the batter than Roach. Some quick maths showed that this gave Bumrah the effect of bowling 3.7mph faster than the speed gun was showing. Cricket has long been played on a pitch that is 22 yards. Bumrah plays on one that is 21.5.

Admittedly, this advantage was spotted because Bumrah is on the extreme, gazillion-jointed end of the scale, enabling him to bowl closer than anyone else in a way that other bowlers can't. But given we pay attention to how wide on the crease a bowler will bowl and also how high a bowler's release point is, surely we should know how close a bowler is bowling to the batter, given it is the single easiest way of apparently increasing pace.

This effect is measured in baseball. In fact, everything is. While cricket shrugs its shoulders and says "I guess we'll never know, folks" for a myriad of data-points, every intangible detail in baseball is known and measured.

How close a pitcher releases the ball to a batter is known as "Extension" and translates to what's known as "Perceived Velocity". Famed pitching coach Tom House believes that, if you can throw the ball one foot closer to the batter, then it equals an extra 3mph for the person at the other end. Tyler Glasnow and Luis Castillo are two pitchers who both throw their fast-ball at 97mph. Glasnow's extension is one of the best in the league and Castillo's is one of the worst. As a result, Glasnow feels like he is throwing at 99mph and Castillo feels like he is throwing at 95mph.Spin rates, which could resolve cricket's heavy-ball phenomenon, are a hugely important measurement in baseball - so much so that they can now be taken into consideration in the selection process.

Even the ultimate intangible, the impact an action has on a batter before the ball has been released, is beginning to be quantified by a biomechanics company known as ProPlayAI, who have started tracking what they call a "deception metric", which measures the amount of time a batter has to see the ball in a pitcher's hand before release.

Mitchell Johnson was ferociously quick during the 2013-14 Ashes Getty Images

Mitchell Johnson was ferociously quick during the 2013-14 Ashes Getty Images

The culmination of all these factors comes in the form of a pitcher named Yusemeiro Petit, described by baseball writer Ben Lindbergh as "the poster boy for the power of deception".

Petit's average fast-ball is 87mph. A whole 7mph slower than the rest of the league. He is 37 years old and over 500 games into his career. And he has made it this far, not by being a force of nature but by representing the mystery of it. He is one of those alien fishes at the bottom of the ocean that has lived forever and we don't know why.

In the 2005 edition of the Prospect Handbook, Baseball America, which is the sport's annual guide on the young players to look out for, Petit was described as leaving "batters and scouts scratching their heads ... Nothing about it [his fast-ball] appears to be exceptional - except how hitters never seem to get a good swing against it."

Fast forward to the present day and the reasons for Petit's success are beginning to be decoded. Simply put, Lindbergh describes him as a "hider and a strider". Throwing the ball far closer to home plate than would be expected and giving the batter little to no sight of the ball in the process. The result of which is a pitcher who is far quicker than the speed gun would lead you to believe.

****

All of this isn't to say that the speed gun is useless. It isn't. But it represents different things to different people. As a broadcasting tool, it's an excellent way of telling a story in a bite-size chunk. And for a bowler, it represents the result of their process. Get everything right and watch that number go up.

For batters, however, it represents part of the process that leads to their result. Yes, the speed of a ball upon release is important. But we know that there are other factors at play, because the players at the receiving end of it say so. And ultimately, who would you rather face? A bowler that a machine says is fast? Or one that a human says feels even faster?

South Africa's Andrew Hall is on strike against Brett Lee at the Wanderers stadium in Johannesburg. The ball is bowled and Hall tucks it into the leg side before setting off for a gentle single.

As he jogs to the other end he hears a belated cheer from the crowd. Confused, he looks around to see the big screen displaying an announcement. He has just faced the fastest ball ever to have been bowled at the Wanderers.

Still confused, Hall's eyes move from the screen to Lee and they trade a quizzical look: "There's no way that was that quick."

The next ball, Lee runs in and bowls a bouncer to Gary Kirsten that flies past his face. Lee and Hall catch each other's eye once more,

"That one was."

You see, the speed gun is the movie adaptation of your favourite book. Yes, it tells the story. But it doesn't tell the full one.

****

"A lot of what makes Test players special happens before the ball comes out of a bowler's hand."

Those are the words of England analyst Nathan Leamon, speaking on Jarrod Kimber's Red Inker podcast. As a starting point, it shines a light on one of the limitations of the speed gun. It only tells us how fast a ball is at the point of release and tells us nothing about what has happened before or what happens after.

And what happens before is crucial. It is very easy to think of facing fast bowling as primarily a reactive skill. In fact, read any article on quick bowling and it will invariably say you only have 0.4 seconds to react to a 90mph delivery.

But what does that mean? No one can compute information in 0.4 seconds. It's beyond our realm of thinking in the same way that looking out of an aeroplane window doesn't give you vertigo because you're simply too high up for your brain to process it.

However, the reason it's possible is because, whilst you may only have 0.4 seconds to react, you have a lot longer than that to plan. And the best in the world plan exceptionally well.

Hall describes a training method that South Africa would use in order to be able to associate a bowler's release point with length. After a ball was bowled, they'd walk down the wicket and place a cone or mark a spot with their bat where they believed the ball had landed. The coach would confirm it or correct what the player thought.

The idea is in essence basic trigonometry. Over time, you learn to associate that if a bowler releases the ball with his arm at 12 o'clock, the delivery would be full. If he releases the ball at 1 o'clock, it would be short. It's a process designed to consciously train the subconscious, and Jacques Kallis was the best at it.

"Whether he played and missed," Hall says, "or left it, or ducked out the way, he'd be able to come down the track and isolate a rough area of where that ball had landed. And the reason he was so good at it is he became really sharp at picking up length and he made some bowlers look slower because of that. Because as they let go of the ball, he knew within a couple of inches where it was going to land."

Jasprit Bumrah roars after having Joe Root caught in the slips AFP/Getty Images

Jasprit Bumrah roars after having Joe Root caught in the slips AFP/Getty ImagesThere are a number of pre-delivery cues that Hall, as an international player, would be looking out for. Some were obvious tells, such as a bowler running in that bit harder before bowling a bouncer; others more subtle, like a bowler's head falling away in their action so they were able to push the ball into the batter and bowl an inswinger.

These cues weren't restricted to fast bowlers either. When talking about how to face Muthiah Muralidaran, Hall explains that one of the cues the South Africans would look out for was where his right elbow would be pointing as he entered his delivery stride. If it was pointing out at 90 degrees with his hand by his ear lobe, that was the sign that Muralitharan was going to bowl his off-spinner. If his elbow was pointing down towards the batter, it was probably a doosra coming up.

"You still wouldn't be able to play it half the time," Hall adds, "but you had an idea."

And some bowlers give you more of these cues than others, meaning a bowler at 87mph may feel quicker than one at 90mph if they give the batter fewer clues in their action.

Mark Ramprakash spoke of this when comparing his experience of facing Lee and Jason Gillespie in the 2001 Ashes. Lee was the faster bowler of the two, but his textbook action, with the ball always in sight, meant that Ramprakash felt he could consistently time his pre-delivery movement. But when he faced Gillespie, despite his being slower on the speed gun, it felt quicker. And this was because Gillespie would appear almost to release the ball before he'd really landed on the ground, throwing off Ramprakash's timings. When facing Lee, Ramprakash was planning. But when he was facing Gillespie, he was reacting.

In simple terms, there's a correlation between a bowler being "different" and the feeling that they are faster than they actually are. Batters are brought up on a diet of right-arm-over bowling that is released from nigh-on the same area, ball after ball after ball. Remove that familiarity, and the feeling of speed goes up.

In the Caribbean in 2019, TV showed Jasprit Bumrah's release point was half a metre closer to the batter than Kemar Roach's. This gave Bumrah the effect of bowling 3.7mph faster than the speed gun was showing

"Take Lasith Malinga," Hall says. "If you've not faced him before, you're literally going 'what am I supposed to watch?' But you soon get told, when he gets into his action, to watch the umpire's chest and neck. If you're watching his arm, you're struggling. And that's why in the beginning he'd clean people up and they'd say 'ah, he's quick'. He's not that quick. You just couldn't follow the ball."

****

Another quirk of how we consider pace is that by measuring the speed at which a ball is released, we're not actually measuring how long it takes to reach the batter. And there's a difference.

For instance, if you set up a bowling machine at 85mph and deliver three balls in a row, one of which is a full toss, the second a good length delivery and the third a bouncer, each of the three balls will reach the other end in a different amount of time because when the ball hits the pitch, it slows down. And the steeper that impact is, the more it will slow. So counterintuitively, the bouncer, cricket's scariest delivery, is actually the slowest of the three, whereas the full toss, cricket's worst delivery, is the fastest.

But what we don't know is how different bowlers compare to each other in terms of how much pace they lose off the wicket. The information is out there, but it's just not readily available. Angus Reid from VirtualEye - the company that provides ball-tracking data for Test matches in Australia - recalls how, during Naseem Shah's Test debut for Pakistan, they did a piece for broadcast comparing how he and Australia's Pat Cummins were releasing the ball at very similar speeds, but Shah was reaching the batter faster due to a combination of his height, ball trajectory and "skiddy" nature.

Steven Smith was pinned by a Jofra Archer bouncer at Lord's in 2019 Getty Images

Steven Smith was pinned by a Jofra Archer bouncer at Lord's in 2019 Getty ImagesAnd we know from player anecdotes that these things matter. Hall explains how bowlers will sometimes bowl their bouncer with a cross-seam in the hope that the ball lands on the lacquer and loses less pace when it pitches. It is the same notion that Joe Root expressed earlier this year when he said India's spinner Axar Patel was beating England for pace in the pink-ball Test at Ahmedabad, because the skid off the lacquer gave the feeling that the ball was "gathering pace" off the wicket.

Conversely, many bowlers are said to bowl a "heavy ball", whereby batters feel that the ball is "hitting the bat harder" than expected. One such bowler was New Zealand bowler Iain O'Brien, who believes this was a consequence of the ball kicking up off the pitch and striking the blade higher than anticipated, due to more backspin being imparted upon release. Such was the backspin that Andrew Flintoff imparted on the ball, in the lead up to the 2005 Ashes he was accused of chucking as his wrist would snap so dramatically at the point of delivery.

This is one of the difficulties of trying to express the feeling of speed to a wider audience. For the spectator, it's merely a number because we have no other frame of reference. But for the batter, it's an experience. A moment in time that is almost over before it's begun.

One former international cricketer laughed when asked whether he would check the speed gun after facing a delivery. "Why would I need the speed gun to tell me if a ball was fast? I was the one who just faced it."

****

The final piece of the puzzle concerns the ball's release point.

When India were touring the Caribbean in 2019, TV showed an overlay of Jasprit Bumrah's release point compared to Kemar Roach's, demonstrating that Bumrah was bowling the ball half a metre closer to the batter than Roach. Some quick maths showed that this gave Bumrah the effect of bowling 3.7mph faster than the speed gun was showing. Cricket has long been played on a pitch that is 22 yards. Bumrah plays on one that is 21.5.

Admittedly, this advantage was spotted because Bumrah is on the extreme, gazillion-jointed end of the scale, enabling him to bowl closer than anyone else in a way that other bowlers can't. But given we pay attention to how wide on the crease a bowler will bowl and also how high a bowler's release point is, surely we should know how close a bowler is bowling to the batter, given it is the single easiest way of apparently increasing pace.

This effect is measured in baseball. In fact, everything is. While cricket shrugs its shoulders and says "I guess we'll never know, folks" for a myriad of data-points, every intangible detail in baseball is known and measured.

How close a pitcher releases the ball to a batter is known as "Extension" and translates to what's known as "Perceived Velocity". Famed pitching coach Tom House believes that, if you can throw the ball one foot closer to the batter, then it equals an extra 3mph for the person at the other end. Tyler Glasnow and Luis Castillo are two pitchers who both throw their fast-ball at 97mph. Glasnow's extension is one of the best in the league and Castillo's is one of the worst. As a result, Glasnow feels like he is throwing at 99mph and Castillo feels like he is throwing at 95mph.Spin rates, which could resolve cricket's heavy-ball phenomenon, are a hugely important measurement in baseball - so much so that they can now be taken into consideration in the selection process.

Even the ultimate intangible, the impact an action has on a batter before the ball has been released, is beginning to be quantified by a biomechanics company known as ProPlayAI, who have started tracking what they call a "deception metric", which measures the amount of time a batter has to see the ball in a pitcher's hand before release.

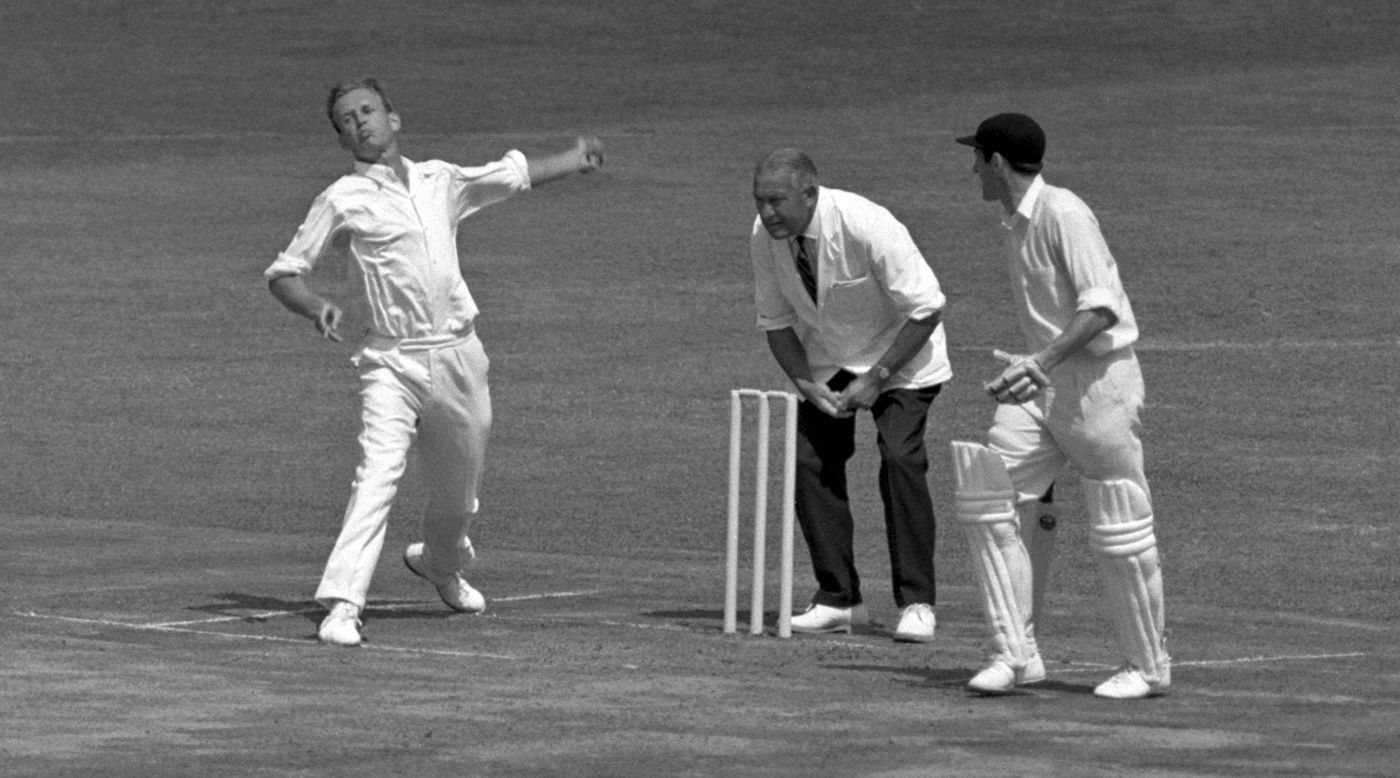

Mitchell Johnson was ferociously quick during the 2013-14 Ashes Getty Images

Mitchell Johnson was ferociously quick during the 2013-14 Ashes Getty ImagesThe culmination of all these factors comes in the form of a pitcher named Yusemeiro Petit, described by baseball writer Ben Lindbergh as "the poster boy for the power of deception".

Petit's average fast-ball is 87mph. A whole 7mph slower than the rest of the league. He is 37 years old and over 500 games into his career. And he has made it this far, not by being a force of nature but by representing the mystery of it. He is one of those alien fishes at the bottom of the ocean that has lived forever and we don't know why.

In the 2005 edition of the Prospect Handbook, Baseball America, which is the sport's annual guide on the young players to look out for, Petit was described as leaving "batters and scouts scratching their heads ... Nothing about it [his fast-ball] appears to be exceptional - except how hitters never seem to get a good swing against it."

Fast forward to the present day and the reasons for Petit's success are beginning to be decoded. Simply put, Lindbergh describes him as a "hider and a strider". Throwing the ball far closer to home plate than would be expected and giving the batter little to no sight of the ball in the process. The result of which is a pitcher who is far quicker than the speed gun would lead you to believe.

****

All of this isn't to say that the speed gun is useless. It isn't. But it represents different things to different people. As a broadcasting tool, it's an excellent way of telling a story in a bite-size chunk. And for a bowler, it represents the result of their process. Get everything right and watch that number go up.

For batters, however, it represents part of the process that leads to their result. Yes, the speed of a ball upon release is important. But we know that there are other factors at play, because the players at the receiving end of it say so. And ultimately, who would you rather face? A bowler that a machine says is fast? Or one that a human says feels even faster?

Friday, 9 July 2021

Friday, 4 September 2020

Spin Bowlers' Interviews by Murali Kartik

Ravi Ashwin

Part 1

Part 2

Graeme Swann

Part 1

Part 2

Daniel Vettori

Ramesh Powar and Rahul Sanghvi

Part 1

Part 2

Dilip Doshi

Maninder Singh

Part 1

Part 2

Harbhajan Singh

Part 1

Part 2

Muttiah Muralitharan

Part 1

Part 2

Laxman Sivaramakrishnan

Part 1

Part 2

Amit Mishra

Part 1

Part 2

Saqlain Mushtaq

Part 1

Part 2

Sunday, 8 July 2018

Why are modern batsmen weak against legspin in the short formats?

Ian Chappell in Cricinfo

It's not only the range of strokes that has dramatically evolved in short-format batting but also the mental approach. Contrast the somnambulistic approach of Essex's Brian Ward in a 1969 40-over game with England's record-breaking assault on the Australian bowling at Trent Bridge recently.

Ward decided that Somerset offspinner Brian Langford was the danger man in the opposition attack, and eight consecutive maidens resulted, handing the bowler the never-to-be-repeated figures of 8-8-0-0. On the other hand England's batsmen this year displayed no such inhibitions in rattling up 481 off 50 overs, and Australia's bowlers, headed by Andrew Tye, with 9-0-100-0, were pummelled.

Nevertheless one thing has remained constant in the short formats: a wariness around spin bowling, although currently it's more likely to be the wrist variety than fingerspin.

The list of successful wristspinners in short-format cricket is growing rapidly and there have been some outstanding recent performances. Afghanistan's Rashid Khan was the joint leading wicket-taker in the BBL; England's Adil Rashid (along with spin-bowling companion Moeen Ali), took the most wicketsin the recent whitewash of Australia; and in successive T20Is against England, India's duo of Yuzvendra Chahal and Kuldeep Yadav have claimed the rare distinction of a five-wicket haul. It's a trail of destruction that have would gladdened the heart of Bill "Tiger" O'Reilly, a great wristspinner himself and the most insistent promoter of the art there has ever been.

Wristspinners are extremely successful in the shorter formats and are being eagerly sought after for the many T20 leagues. Their enormous success is mostly down to the deception they provide, since they are able to turn it from both leg and off with only a minimal change of action. Kuldeep provided a perfect example when he bamboozled both Jonny Bairstow and Joe Root with successive wrong'uns in the opening T20 at Old Trafford.

The fact that Bairstow - a wicketkeeper by trade - was deceived by the wrong'un is symptomatic of a malaise that is sweeping international batting - a general inability to read wristspinners. This failing is not only the root cause of wicket loss from mishits but also contributes to a desirable bowling economy rate for the bowlers, as batsmen are hesitant to attack a delivery they are unsure about. This inability to read wristspinners is mystifying.

If a batsman watches the ball out of the hand, the early warning signals are available. A legbreak is delivered with the back of the hand turned towards the bowler's face, while with the wrong'un, it's facing the batsman. As a further indicator, the wrong'un, because it's bowled out of the back of the hand, has a slightly loftier trajectory. Final confirmation is provided by the seam position, which is tilted towards first slip for the legspinner, and leg slip for the wrong'un. Any batsman waiting to pick the delivery off the pitch is depriving himself of scoring opportunities and putting his wicket in danger.

When Shane Warne was at his devastating peak, fans marvelled at his repertoire and said it was the main reason for his success. "Picking him is the easy part," I explained, "it's playing him that's difficult."

Richie Benaud, another master of the art, summed up spin bowling best: "It's the subtle variations," he proffered, "that bring the most success."

O'Reilly was not only an aggressive leggie but also a wily one, and he bent his back leg when he wanted to vary his pace. This action altered his release point without slowing his arm speed, and consequently it was difficult for the batsman to detect the subtle variation.

This type of information is crucial to successful batsmanship, but following Kuldeep's demolition job, Jos Buttler said it might take one or two games for English batsmen to get used to the left-armer. This is an indictment of the current system for developing young batsmen, where you send them into international battle minus a few important tools.

It's not only the range of strokes that has dramatically evolved in short-format batting but also the mental approach. Contrast the somnambulistic approach of Essex's Brian Ward in a 1969 40-over game with England's record-breaking assault on the Australian bowling at Trent Bridge recently.

Ward decided that Somerset offspinner Brian Langford was the danger man in the opposition attack, and eight consecutive maidens resulted, handing the bowler the never-to-be-repeated figures of 8-8-0-0. On the other hand England's batsmen this year displayed no such inhibitions in rattling up 481 off 50 overs, and Australia's bowlers, headed by Andrew Tye, with 9-0-100-0, were pummelled.

Nevertheless one thing has remained constant in the short formats: a wariness around spin bowling, although currently it's more likely to be the wrist variety than fingerspin.

The list of successful wristspinners in short-format cricket is growing rapidly and there have been some outstanding recent performances. Afghanistan's Rashid Khan was the joint leading wicket-taker in the BBL; England's Adil Rashid (along with spin-bowling companion Moeen Ali), took the most wicketsin the recent whitewash of Australia; and in successive T20Is against England, India's duo of Yuzvendra Chahal and Kuldeep Yadav have claimed the rare distinction of a five-wicket haul. It's a trail of destruction that have would gladdened the heart of Bill "Tiger" O'Reilly, a great wristspinner himself and the most insistent promoter of the art there has ever been.

Wristspinners are extremely successful in the shorter formats and are being eagerly sought after for the many T20 leagues. Their enormous success is mostly down to the deception they provide, since they are able to turn it from both leg and off with only a minimal change of action. Kuldeep provided a perfect example when he bamboozled both Jonny Bairstow and Joe Root with successive wrong'uns in the opening T20 at Old Trafford.

The fact that Bairstow - a wicketkeeper by trade - was deceived by the wrong'un is symptomatic of a malaise that is sweeping international batting - a general inability to read wristspinners. This failing is not only the root cause of wicket loss from mishits but also contributes to a desirable bowling economy rate for the bowlers, as batsmen are hesitant to attack a delivery they are unsure about. This inability to read wristspinners is mystifying.

If a batsman watches the ball out of the hand, the early warning signals are available. A legbreak is delivered with the back of the hand turned towards the bowler's face, while with the wrong'un, it's facing the batsman. As a further indicator, the wrong'un, because it's bowled out of the back of the hand, has a slightly loftier trajectory. Final confirmation is provided by the seam position, which is tilted towards first slip for the legspinner, and leg slip for the wrong'un. Any batsman waiting to pick the delivery off the pitch is depriving himself of scoring opportunities and putting his wicket in danger.

When Shane Warne was at his devastating peak, fans marvelled at his repertoire and said it was the main reason for his success. "Picking him is the easy part," I explained, "it's playing him that's difficult."

Richie Benaud, another master of the art, summed up spin bowling best: "It's the subtle variations," he proffered, "that bring the most success."

O'Reilly was not only an aggressive leggie but also a wily one, and he bent his back leg when he wanted to vary his pace. This action altered his release point without slowing his arm speed, and consequently it was difficult for the batsman to detect the subtle variation.

This type of information is crucial to successful batsmanship, but following Kuldeep's demolition job, Jos Buttler said it might take one or two games for English batsmen to get used to the left-armer. This is an indictment of the current system for developing young batsmen, where you send them into international battle minus a few important tools.

Tuesday, 29 August 2017

Spin Bowlers - Going through life as an individual

Suresh Menon in The Hindu

Spin bowlers tend to be like French verbs — they follow rules peculiar to their type, and the exceptions to the rule are fascinating. Often exceptions have rules too. Shane Warne didn’t need to bowl an off-break; Graeme Swann didn’t bowl the leg-break, not even the fashionable doosra. Yet cricket’s great mystery bowlers have been the spinners, not the fast men who might threaten life and limb, but seldom leave the batsman feeling foolish.

It would have been nice to get into the heads of India’s leading batsmen Virat Kohli and K.L. Rahul after they were beaten and bowled in one magical over by Sri Lanka’s latest mystery spinner, Mahamarakkala Kurukulasooriya Patabendige Akila Dananjaya Perera.

It wasn’t the classical duel where the bowler teases and tantalises, torments and mocks over a period before the kill. There isn’t time for that in a limited overs game. Here, speed of execution is of the essence, and both batsmen were fooled by an apparently innocuous delivery. There was something gentle about it all. A slight drift, a final dip, and batsmen with a reputation for dominating spin bowling were done in, playing the wrong line.

Perhaps ‘mystery’ applies to spin bowlers in general. The flighted delivery bowled above the eye line works against the steady head and tricks the batsman into believing the ball will pitch closer to him than it actually does. Then there is the problem of figuring out which way it will turn.

To those watching from the outside it is a cause for wonder that a slow delivery, sometimes spinning, often not, hits the stumps ignoring the bat and pads. It is one of the most satisfying sights in cricket, to watch a Goliath, complete with protective gear fall prey to a bowler whose greatest deception sometimes is that there is no deception at all.

Dananjaya is an off-break bowler who also bowls leg-breaks, doosras and the carom ball. He will be studied with great care by batsmen who will work out where his shoulder and feet and hands are at the time of delivery.

In modern cricket, mystery spinners need to be able to beat both the batsmen and the coaches armed with their computers. The most artistic of deliveries can be reduced to their mathematical specifics. Before the advent of technology, the average spinner sometimes needed to develop ‘mystery’ deliveries to be successful. Now the ‘mystery’ spinner needs to get back to the roots of his craft, focusing on the traditional.

It is a lesson the phenomenally successful Test off-spinner R. Ashwin has to absorb if he hopes to be a permanent fixture in the one-day side.

‘Mystery’ spinners through history, from Jack Iverson to Johnny Gleeson to Ajantha Mendis have tended to have early success, and then faded out. Once the opposition worked them out, they lacked the control over their basic craft to take wickets.

Iverson’s bowling action was characterised as that of a man flicking out a burnt cigarette. That might have been the original carom ball, except that using his long middle finger and thumb he could turn the ball from off to leg. Some batsmen began to play him as an off spinner although he took wickets with his leg break and top spinner. He was sorted out in the inter-state matches in Australia by Arthur Morris and Keith Miller — in the days when players had to think for themselves, who recognised the top spinner as the one tossed up higher and went hard at the bowler.

Gleeson, who also had a long middle finger and could bowl the Iverson delivery in the 1960s, strengthened his fingers by milking cows. Despite their short stints, the game has been the richer for their presence.

Increasingly, cookie-cutter coaching tends to convert the unorthodox spinner into something more comprehensible. As David Frith says, “Every young spinner turned into a colourless medium-pacer constitutes a crime against a beautiful game.”

The one country where the unorthodox is not just accepted but actively encouraged is Sri Lanka. Think Muttiah Muralitharan, or Lasith Malinga or Mendis, bowlers who were allowed to remain themselves with no coach attempting to iron out so-called deficiencies.

It might sound counter-intuitive, but spinners with too many variations tend not to be as successful as those with a few, of which they are the masters. It is the fox versus the hedgehog theory all over again. The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing. Sometimes in cricket, it is smarter to be the hedgehog.

“There seemed to be an absence of orthodoxy about them, and they were able to meander through life as individuals, not civil servants.” That is a line from the Australian spinner Arthur Mailey. He was speaking about spinners in general. It applies equally to Dananjaya and his special kind.

Spin bowlers tend to be like French verbs — they follow rules peculiar to their type, and the exceptions to the rule are fascinating. Often exceptions have rules too. Shane Warne didn’t need to bowl an off-break; Graeme Swann didn’t bowl the leg-break, not even the fashionable doosra. Yet cricket’s great mystery bowlers have been the spinners, not the fast men who might threaten life and limb, but seldom leave the batsman feeling foolish.

It would have been nice to get into the heads of India’s leading batsmen Virat Kohli and K.L. Rahul after they were beaten and bowled in one magical over by Sri Lanka’s latest mystery spinner, Mahamarakkala Kurukulasooriya Patabendige Akila Dananjaya Perera.

It wasn’t the classical duel where the bowler teases and tantalises, torments and mocks over a period before the kill. There isn’t time for that in a limited overs game. Here, speed of execution is of the essence, and both batsmen were fooled by an apparently innocuous delivery. There was something gentle about it all. A slight drift, a final dip, and batsmen with a reputation for dominating spin bowling were done in, playing the wrong line.

Perhaps ‘mystery’ applies to spin bowlers in general. The flighted delivery bowled above the eye line works against the steady head and tricks the batsman into believing the ball will pitch closer to him than it actually does. Then there is the problem of figuring out which way it will turn.

To those watching from the outside it is a cause for wonder that a slow delivery, sometimes spinning, often not, hits the stumps ignoring the bat and pads. It is one of the most satisfying sights in cricket, to watch a Goliath, complete with protective gear fall prey to a bowler whose greatest deception sometimes is that there is no deception at all.

Dananjaya is an off-break bowler who also bowls leg-breaks, doosras and the carom ball. He will be studied with great care by batsmen who will work out where his shoulder and feet and hands are at the time of delivery.

In modern cricket, mystery spinners need to be able to beat both the batsmen and the coaches armed with their computers. The most artistic of deliveries can be reduced to their mathematical specifics. Before the advent of technology, the average spinner sometimes needed to develop ‘mystery’ deliveries to be successful. Now the ‘mystery’ spinner needs to get back to the roots of his craft, focusing on the traditional.

It is a lesson the phenomenally successful Test off-spinner R. Ashwin has to absorb if he hopes to be a permanent fixture in the one-day side.

‘Mystery’ spinners through history, from Jack Iverson to Johnny Gleeson to Ajantha Mendis have tended to have early success, and then faded out. Once the opposition worked them out, they lacked the control over their basic craft to take wickets.

Iverson’s bowling action was characterised as that of a man flicking out a burnt cigarette. That might have been the original carom ball, except that using his long middle finger and thumb he could turn the ball from off to leg. Some batsmen began to play him as an off spinner although he took wickets with his leg break and top spinner. He was sorted out in the inter-state matches in Australia by Arthur Morris and Keith Miller — in the days when players had to think for themselves, who recognised the top spinner as the one tossed up higher and went hard at the bowler.

Gleeson, who also had a long middle finger and could bowl the Iverson delivery in the 1960s, strengthened his fingers by milking cows. Despite their short stints, the game has been the richer for their presence.

Increasingly, cookie-cutter coaching tends to convert the unorthodox spinner into something more comprehensible. As David Frith says, “Every young spinner turned into a colourless medium-pacer constitutes a crime against a beautiful game.”

The one country where the unorthodox is not just accepted but actively encouraged is Sri Lanka. Think Muttiah Muralitharan, or Lasith Malinga or Mendis, bowlers who were allowed to remain themselves with no coach attempting to iron out so-called deficiencies.

It might sound counter-intuitive, but spinners with too many variations tend not to be as successful as those with a few, of which they are the masters. It is the fox versus the hedgehog theory all over again. The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing. Sometimes in cricket, it is smarter to be the hedgehog.

“There seemed to be an absence of orthodoxy about them, and they were able to meander through life as individuals, not civil servants.” That is a line from the Australian spinner Arthur Mailey. He was speaking about spinners in general. It applies equally to Dananjaya and his special kind.

Monday, 6 March 2017

Turn, flight and parabola separate a genuine spinner from an ordinary one

Nagraj Gollapudi in Cricinfo

Rajinder Goel, Padmakar Shivalkar and V V Kumar, three spinners who traumatised batsmen from the 1960s to the late-1980s, will be honoured by the BCCI on March 8 for their services to Indian cricket. Goel and Shivalkar, both left-arm spinners, will be given the CK Nayudu Lifetime Achievement Award. Kumar, a legspinner who played two Tests for India, will be given a special award for his "yeoman" service

In the following interview, the three talk about learning the basics of spin, their favourite practitioners of the art, and what has changed since their time.

What makes a good spinner?

Rajinder Goel - Hard work, practice, and some intellect on how to play the batsman - these are mandatory. Without practice you will not be able to master line and length, which are key to defeat the batsman.

Padmakar Shivalkar - Your basics of line and length need to be in place. The delivery needs to have a loop. This loop, which we used to call flight, needs to be a constant. Over the years, you increase this loop, adjust it. You lock the batsman first and then spread the web - he gets trapped steadily. But these things are not learned easily. It takes years and years of work before you reach the top level.

VV Kumar - There are many components involved. A spinner has to spend a lot of time in the nets. You can possibly become a spinner by participating in a practice session for a couple of hours. But you cannot become a real good spinner. A spinner must first understand what exactly is spinning the ball. A real spinner should possess the following qualities, otherwise he can only be termed a roller.

The number one thing is to have revolutions on the ball. Then you overspin your off- or legbreaks. There are two types when it comes to imparting spin: overspin and sidespin. A ball that is sidespun is mostly delivered with an improper action and is against the fundamentals of spin bowling. A real spinner will overspin his off- or legbreak, which, when it hits the ground, will have bounce, a lot of drift and turn. A sidespun delivery will only break - it will take a deviation. An overspun delivery will spin, bounce and then turn in or away sharply.

Then we come to control. The spinner needs to have control over the flight, the parabola. Flight does not mean just throwing the ball in the air. Flight means you spin the ball in such a way that you impart revolutions to the ball with the idea of breaking the ball to exhibit the parabola or dip. By doing that you put the batsman in two minds - whether he should come forward or stay back. But if the flight does not land properly, it can end up in a full toss.

The concept of a good spinner also includes bowling from over the wicket to both the right- and left-handed batsman. The present trend is for spinners to come round the wicket, which is negative and indicates you do not want to get punished. A spin bowler will have to give runs to get a wicket, but he should not gift it.

A spinner is not complete without mastering line and length. He must utilise the field to make the batsman play such strokes that will end up in a catch. That depends on the line he is bowling, his ability to flight the ball, to make the batsman come forward, or spin the ball to such an extent that the batsman probably tries to cut, pull, drive or edge. That is the culmination of a spinner planning and executing the downfall of a good batsman. For all this to happen, all the above fundamentals are compulsory. Turn, flight and parabola separate a genuine spinner from an ordinary spinner.

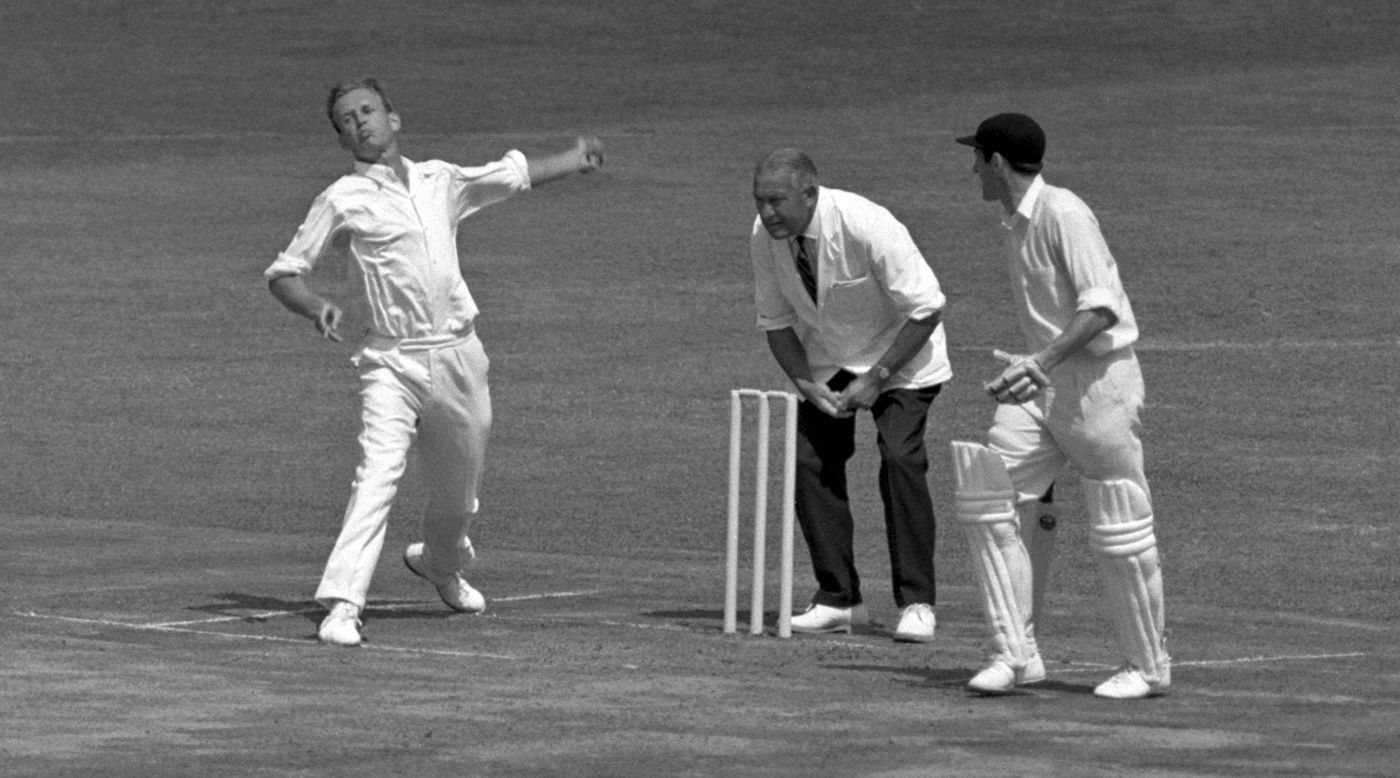

Shivalkar: "Vishy had amazing bat speed... he had a sharp eye. [Vijay] Manjrkear called him an artist" © Getty Images

Shivalkar: "Vishy had amazing bat speed... he had a sharp eye. [Vijay] Manjrkear called him an artist" © Getty Images

Did you have a mentor who helped you become a good spinner?

Goel - Lala Amarnath. It was 1957. I was in grade ten. I was part of the all-India schools camp in Chail in Himachal Pradesh. He taught me the basics of spin bowling. The most important thing he taught me was to come across the umpire and bowl from close to the stumps. He said with that kind of action I would be able to use the crease well and could play with the angles and the length easily.

Kumar - I am self-taught, and I say that without any arrogance. I started practising by spinning a golf ball against the wall. It would come back in a different direction. The ten-year-old in me got curious from that day about how that happened. I started reading good books by former players, like Eric Hollies, Clarrie Grimmett and Bill O' Reilly. Of course, my first book was The Art of Cricket by Don Bradman. That is how I equipped myself with the knowledge and put it in practice with a ball in hand.

Shivalkar - It was my whole team at Shivaji Park Gymkhana who made me what I became. If there was a bad ball, and there were many when I was a youngster in 1960-61, I learned a lot from what senior players said, their gestures, their body language. [Vijay] Manjrekar, [Manohar] Hardikar, [Chandrakant] Patankar would tell me: "Shivalkar, watch how he [the batsman] is playing. Tie him up." "Kay kartos? Changli bowling tak [What are you doing? Bowl well]," they would say, at times widening their eyes, at times raising their voice. I would obey that, but I would tell them I was trying to get the batsman out. You cannot always prevail over the batsman, but I cannot ever give up, I would tell myself.

What was your favourite mode of dismissal?

Goel - My strength was to attack the pads. I would maintain the leg-and-middle line. Batsmen who attempted to sweep or tried to play against the spin, I had a good chance of getting them caught in the close-in positions, or even get them bowled. I used to get bat-pad catches frequently, so I would call that my favourite.

"Flight means you spin the ball in such a way that you impart revolutions to the ball with the idea of the breaking the ball to exhibit the dip. By doing that you put the batsman in two minds - whether he should come forward or stay back"

VV KUMAR

Kumar - My best way of getting a batsman out was to make him play forward and lure him to drive. Whether it was a quicker, flighted or flat delivery, I always tried to get the batsman on the front foot. Plenty of my wickets were caught at short leg, fine leg and short extra cover - that shows the batsman was going for the drives. I would not allow him to cut or pull. I would get these wickets through well-spun legbreaks, googlies, offspinners. You have to be very clear about your control and accuracy, otherwise you will be hit all over the place. You should always dominate the batsman. You have to play on his mind. Make him think it is a legbreak and instead he is beaten by flight and dip.

Shivalkar - I used to enjoy getting the batsman stumped. With my command over the loop, batsmen would step out of the crease and get trapped, beaten and stumped.

Tell us about one of your most prized wickets.

Goel - I was playing for State Bank of India against ACC (Associated Cement Companies) in the Moin-ud-Dowlah Gold Cup semi-finals in 1965 in Hyderabad. Polly saab [Polly Umrigar] was playing for ACC. He was a very good player of spin. He was playing well till our captain [Sharad] Diwadkar threw the second new ball to me. I got it to spin immediately and rapped Polly saab on the pads as he attempted to play me on the back foot. It was difficult to force a batsman like him to miss a ball, so it was a wicket I enjoyed taking.

Kumar - Let me talk about the wicket I did not get but one I cherish to this day. I was part of the South Zone team playing against the West Indians in January 1959 at Central College Ground in Bangalore. Garry Sobers came in to bat after I had got Conrad Hunte. I was thrilled and nervous to bowl to the best batsman. Gopi [CD Gopinath] told me to bowl as if I was bowling in any domestic match and not get bothered by the gifted fellow called Sobers.

The first ball was a legbreak, pitched outside off stump. Sobers moved across to pull me. Second ball was a topspinner, a full-length ball on the off stump. He went on the leg side and pushed it past point for four. The third ball was quickish, which he defended. Next, I delivered a googly on the middle stump. Garry came outside to drive, but the ball took the parabola and dipped. He checked his stroke and in the process sent me a simple, straightforward return catch. The ball jumped out of my hands. I put my hands on my head.

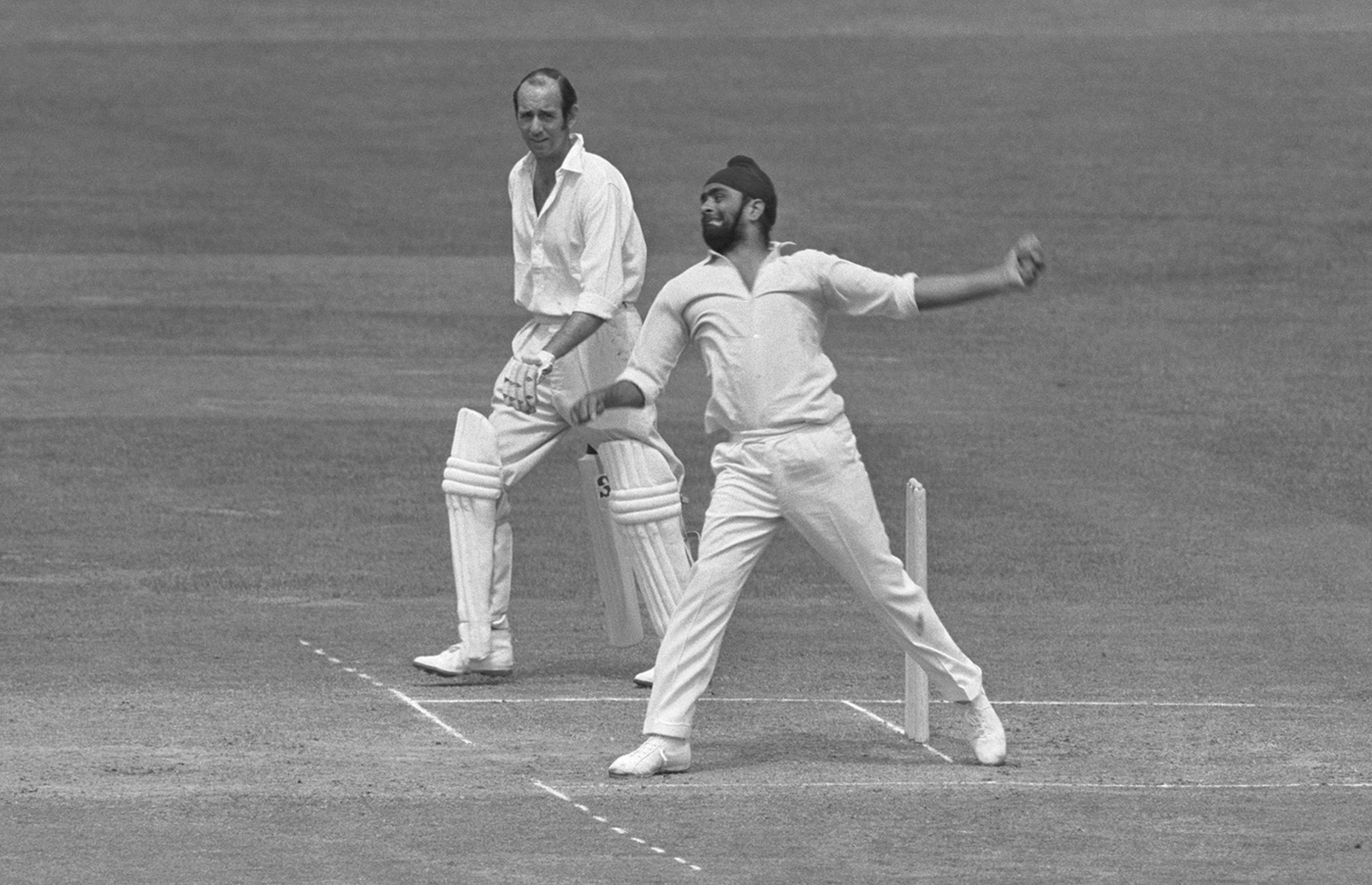

Goel: "There is no better spinner than Bishan Singh Bedi [in photo]. I was in awe of the flight he could impart on the ball. In contrast, I was rapid. Bedi was good on good pitches" © PA Photos

Goel: "There is no better spinner than Bishan Singh Bedi [in photo]. I was in awe of the flight he could impart on the ball. In contrast, I was rapid. Bedi was good on good pitches" © PA Photos

Who was the best spinner you saw bowl?

Goel - There is no better spinner than Bishan Singh Bedi. His high-arm action, the control he had over the ball, the way he would outguess a batsman - I loved Bedi's bowling. I was in awe of the flight he could impart on the ball. In contrast, I was rapid. Bedi was good on good pitches.

Kumar- I will call him my idol. I have not seen anybody else like Subhash Gupte, a brilliant legspinner. I have never seen anybody else reach his standards, including Shane Warne. Sobers himself said he was the best spinner he had ever played. In those days he operated on pitches that were absolutely dead tracks. It was Gupte's ability to adjust and adapt on any kind of surface, his perseverance and the variety he had - my goodness, no one came near to him! That is why he is the greatest spinner I have seen.

Who was the best player of spin you bowled against?

Goel - Ramesh Saxena [Delhi and Bihar] and Vijay Bhosle [Bombay] were two good players of spin. Saxena would never allow the ball to spin. He would reach out to kill the spin. Bhosle was similar, and used to be aggressive against spin.

Kumar - Vijay Manjrekar was probably the best player of spin I encountered. What made him great was the time he had at his disposal to play the ball so late. And by doing that he made the spinner look mediocre.

"No one offers the loop anymore. A consistent loop will always check the batsmen, in T20 too, and also get them out. But you have to be deceptive"

PADMAKAR SHIVALKAR

Shivalkar - [Gundappa] Viswanath. He could change his shot at the last moment. Once, I remember I thought I had him. He was getting ready to cut me on the off stump, but the ball dipped and turned into him. I nearly said "Oooh", thinking he would be either lbw or bowled. But Vishy had amazing bat speed and he managed to get the bat down and the edge whisked past fine leg. He ran two and then looked at me and smiled. He had a sharp eye. [Vijay] Manjrekar called him an artist. Vishy was a jaadugar [magician].

What has changed in spin bowling since the emergence of T20?

Goel - Earlier, we would flight the ball and not get bothered even if we got hit for four. We used to think of getting the batsman out. Now spinners think about arresting the runs. That is one big difference, which is an influence of T20.

Kumar - The three fundamentals I mentioned earlier do not exist in T20 cricket. Spinners are trying to bowl quick and waiting for the batsman to make the mistake. The spinner is not trying to make the batsman commit a mistake by sticking to the fundamentals. In four overs you cannot plan and execute.

Shivalkar - They have become defensive. No one offers the loop anymore. The difference has been brought upon by the bowlers themselves. A consistent loop will always check the batsmen, in T20 too, and also get them out. But you have to be deceptive. At times you should deliver from behind the popping crease, but you cannot allow the batsmen to guess that. That allows you more time for the delivery to land, for your flight to dip. The batsman is put in a fix. I have trapped batsmen that way.

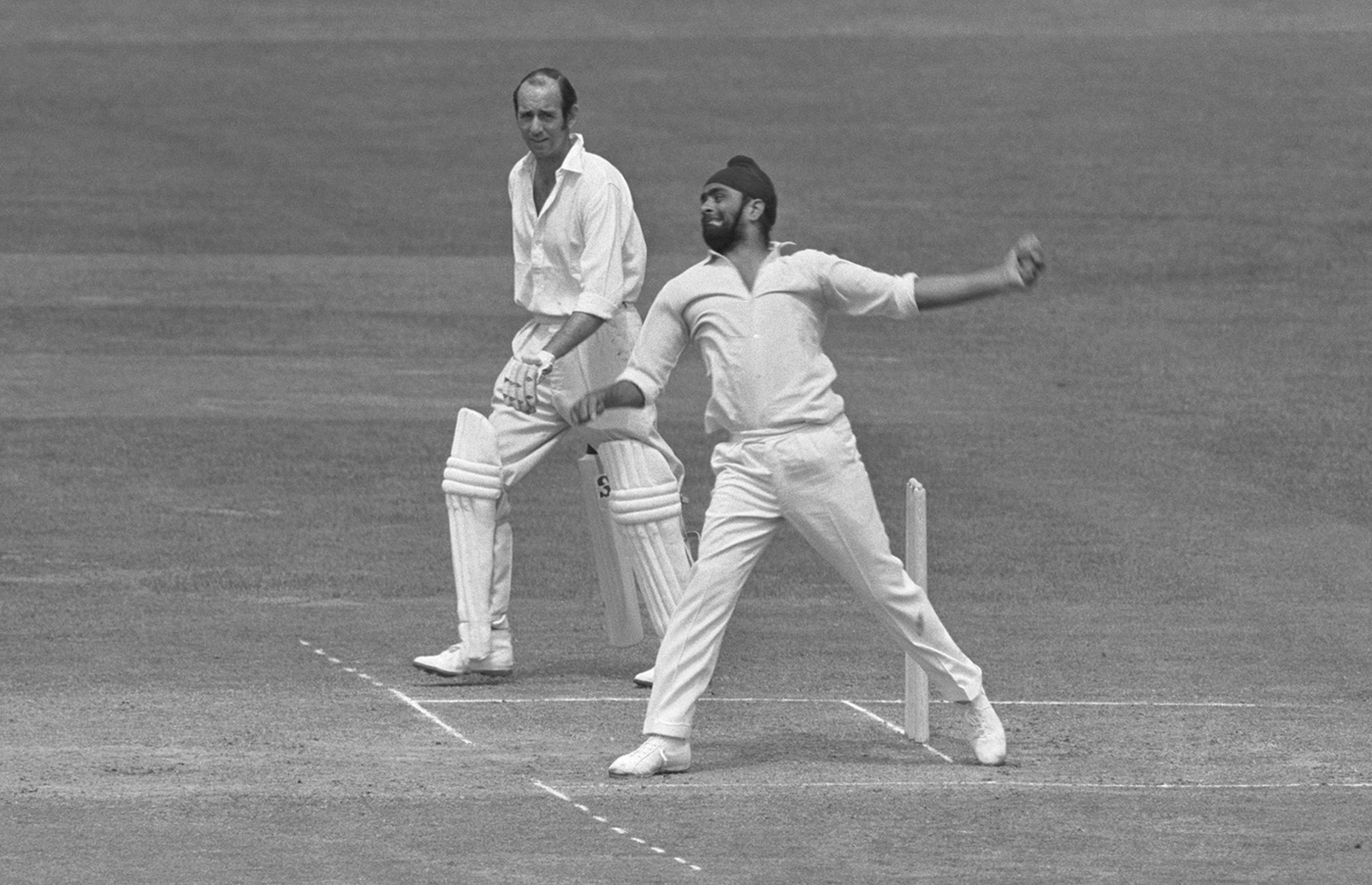

Erapalli Prasanna (left), one of India's famed spin quartet, with Padmakar Shivalkar, who took 580 first-class wickets at 19.69 but never played a Test © AFP

Erapalli Prasanna (left), one of India's famed spin quartet, with Padmakar Shivalkar, who took 580 first-class wickets at 19.69 but never played a Test © AFP

We were playing for Tatas against Indian Oil [Corporation] in the Times Shield. Dilip Vengsarkar was standing at short extra cover. One batsman stepped out, trying to drive me, but Dilip took an easy catch. A couple of overs later he took another catch at the same spot. A third batsman departed in similar fashion in quick succession. Then a lower-order batsman played straight to Dilip, who dropped the catch as he was laughing at the ease with which I was getting the wickets. "Paddy, in my life I have never taken such easy catches," Dilip said, chuckling. The batsmen were not aware I was bowling from behind the crease. If they had noticed, they might have blocked it.

Rajinder Goel, Padmakar Shivalkar and V V Kumar, three spinners who traumatised batsmen from the 1960s to the late-1980s, will be honoured by the BCCI on March 8 for their services to Indian cricket. Goel and Shivalkar, both left-arm spinners, will be given the CK Nayudu Lifetime Achievement Award. Kumar, a legspinner who played two Tests for India, will be given a special award for his "yeoman" service

In the following interview, the three talk about learning the basics of spin, their favourite practitioners of the art, and what has changed since their time.

What makes a good spinner?

Rajinder Goel - Hard work, practice, and some intellect on how to play the batsman - these are mandatory. Without practice you will not be able to master line and length, which are key to defeat the batsman.

Padmakar Shivalkar - Your basics of line and length need to be in place. The delivery needs to have a loop. This loop, which we used to call flight, needs to be a constant. Over the years, you increase this loop, adjust it. You lock the batsman first and then spread the web - he gets trapped steadily. But these things are not learned easily. It takes years and years of work before you reach the top level.

VV Kumar - There are many components involved. A spinner has to spend a lot of time in the nets. You can possibly become a spinner by participating in a practice session for a couple of hours. But you cannot become a real good spinner. A spinner must first understand what exactly is spinning the ball. A real spinner should possess the following qualities, otherwise he can only be termed a roller.

The number one thing is to have revolutions on the ball. Then you overspin your off- or legbreaks. There are two types when it comes to imparting spin: overspin and sidespin. A ball that is sidespun is mostly delivered with an improper action and is against the fundamentals of spin bowling. A real spinner will overspin his off- or legbreak, which, when it hits the ground, will have bounce, a lot of drift and turn. A sidespun delivery will only break - it will take a deviation. An overspun delivery will spin, bounce and then turn in or away sharply.

Then we come to control. The spinner needs to have control over the flight, the parabola. Flight does not mean just throwing the ball in the air. Flight means you spin the ball in such a way that you impart revolutions to the ball with the idea of breaking the ball to exhibit the parabola or dip. By doing that you put the batsman in two minds - whether he should come forward or stay back. But if the flight does not land properly, it can end up in a full toss.

The concept of a good spinner also includes bowling from over the wicket to both the right- and left-handed batsman. The present trend is for spinners to come round the wicket, which is negative and indicates you do not want to get punished. A spin bowler will have to give runs to get a wicket, but he should not gift it.

A spinner is not complete without mastering line and length. He must utilise the field to make the batsman play such strokes that will end up in a catch. That depends on the line he is bowling, his ability to flight the ball, to make the batsman come forward, or spin the ball to such an extent that the batsman probably tries to cut, pull, drive or edge. That is the culmination of a spinner planning and executing the downfall of a good batsman. For all this to happen, all the above fundamentals are compulsory. Turn, flight and parabola separate a genuine spinner from an ordinary spinner.

Shivalkar: "Vishy had amazing bat speed... he had a sharp eye. [Vijay] Manjrkear called him an artist" © Getty Images

Shivalkar: "Vishy had amazing bat speed... he had a sharp eye. [Vijay] Manjrkear called him an artist" © Getty ImagesDid you have a mentor who helped you become a good spinner?

Goel - Lala Amarnath. It was 1957. I was in grade ten. I was part of the all-India schools camp in Chail in Himachal Pradesh. He taught me the basics of spin bowling. The most important thing he taught me was to come across the umpire and bowl from close to the stumps. He said with that kind of action I would be able to use the crease well and could play with the angles and the length easily.

Kumar - I am self-taught, and I say that without any arrogance. I started practising by spinning a golf ball against the wall. It would come back in a different direction. The ten-year-old in me got curious from that day about how that happened. I started reading good books by former players, like Eric Hollies, Clarrie Grimmett and Bill O' Reilly. Of course, my first book was The Art of Cricket by Don Bradman. That is how I equipped myself with the knowledge and put it in practice with a ball in hand.

Shivalkar - It was my whole team at Shivaji Park Gymkhana who made me what I became. If there was a bad ball, and there were many when I was a youngster in 1960-61, I learned a lot from what senior players said, their gestures, their body language. [Vijay] Manjrekar, [Manohar] Hardikar, [Chandrakant] Patankar would tell me: "Shivalkar, watch how he [the batsman] is playing. Tie him up." "Kay kartos? Changli bowling tak [What are you doing? Bowl well]," they would say, at times widening their eyes, at times raising their voice. I would obey that, but I would tell them I was trying to get the batsman out. You cannot always prevail over the batsman, but I cannot ever give up, I would tell myself.

What was your favourite mode of dismissal?

Goel - My strength was to attack the pads. I would maintain the leg-and-middle line. Batsmen who attempted to sweep or tried to play against the spin, I had a good chance of getting them caught in the close-in positions, or even get them bowled. I used to get bat-pad catches frequently, so I would call that my favourite.

"Flight means you spin the ball in such a way that you impart revolutions to the ball with the idea of the breaking the ball to exhibit the dip. By doing that you put the batsman in two minds - whether he should come forward or stay back"

VV KUMAR

Kumar - My best way of getting a batsman out was to make him play forward and lure him to drive. Whether it was a quicker, flighted or flat delivery, I always tried to get the batsman on the front foot. Plenty of my wickets were caught at short leg, fine leg and short extra cover - that shows the batsman was going for the drives. I would not allow him to cut or pull. I would get these wickets through well-spun legbreaks, googlies, offspinners. You have to be very clear about your control and accuracy, otherwise you will be hit all over the place. You should always dominate the batsman. You have to play on his mind. Make him think it is a legbreak and instead he is beaten by flight and dip.

Shivalkar - I used to enjoy getting the batsman stumped. With my command over the loop, batsmen would step out of the crease and get trapped, beaten and stumped.

Tell us about one of your most prized wickets.

Goel - I was playing for State Bank of India against ACC (Associated Cement Companies) in the Moin-ud-Dowlah Gold Cup semi-finals in 1965 in Hyderabad. Polly saab [Polly Umrigar] was playing for ACC. He was a very good player of spin. He was playing well till our captain [Sharad] Diwadkar threw the second new ball to me. I got it to spin immediately and rapped Polly saab on the pads as he attempted to play me on the back foot. It was difficult to force a batsman like him to miss a ball, so it was a wicket I enjoyed taking.

Kumar - Let me talk about the wicket I did not get but one I cherish to this day. I was part of the South Zone team playing against the West Indians in January 1959 at Central College Ground in Bangalore. Garry Sobers came in to bat after I had got Conrad Hunte. I was thrilled and nervous to bowl to the best batsman. Gopi [CD Gopinath] told me to bowl as if I was bowling in any domestic match and not get bothered by the gifted fellow called Sobers.

The first ball was a legbreak, pitched outside off stump. Sobers moved across to pull me. Second ball was a topspinner, a full-length ball on the off stump. He went on the leg side and pushed it past point for four. The third ball was quickish, which he defended. Next, I delivered a googly on the middle stump. Garry came outside to drive, but the ball took the parabola and dipped. He checked his stroke and in the process sent me a simple, straightforward return catch. The ball jumped out of my hands. I put my hands on my head.

Goel: "There is no better spinner than Bishan Singh Bedi [in photo]. I was in awe of the flight he could impart on the ball. In contrast, I was rapid. Bedi was good on good pitches" © PA Photos

Goel: "There is no better spinner than Bishan Singh Bedi [in photo]. I was in awe of the flight he could impart on the ball. In contrast, I was rapid. Bedi was good on good pitches" © PA PhotosWho was the best spinner you saw bowl?

Goel - There is no better spinner than Bishan Singh Bedi. His high-arm action, the control he had over the ball, the way he would outguess a batsman - I loved Bedi's bowling. I was in awe of the flight he could impart on the ball. In contrast, I was rapid. Bedi was good on good pitches.

Kumar- I will call him my idol. I have not seen anybody else like Subhash Gupte, a brilliant legspinner. I have never seen anybody else reach his standards, including Shane Warne. Sobers himself said he was the best spinner he had ever played. In those days he operated on pitches that were absolutely dead tracks. It was Gupte's ability to adjust and adapt on any kind of surface, his perseverance and the variety he had - my goodness, no one came near to him! That is why he is the greatest spinner I have seen.

Who was the best player of spin you bowled against?

Goel - Ramesh Saxena [Delhi and Bihar] and Vijay Bhosle [Bombay] were two good players of spin. Saxena would never allow the ball to spin. He would reach out to kill the spin. Bhosle was similar, and used to be aggressive against spin.

Kumar - Vijay Manjrekar was probably the best player of spin I encountered. What made him great was the time he had at his disposal to play the ball so late. And by doing that he made the spinner look mediocre.

"No one offers the loop anymore. A consistent loop will always check the batsmen, in T20 too, and also get them out. But you have to be deceptive"

PADMAKAR SHIVALKAR

Shivalkar - [Gundappa] Viswanath. He could change his shot at the last moment. Once, I remember I thought I had him. He was getting ready to cut me on the off stump, but the ball dipped and turned into him. I nearly said "Oooh", thinking he would be either lbw or bowled. But Vishy had amazing bat speed and he managed to get the bat down and the edge whisked past fine leg. He ran two and then looked at me and smiled. He had a sharp eye. [Vijay] Manjrekar called him an artist. Vishy was a jaadugar [magician].

What has changed in spin bowling since the emergence of T20?

Goel - Earlier, we would flight the ball and not get bothered even if we got hit for four. We used to think of getting the batsman out. Now spinners think about arresting the runs. That is one big difference, which is an influence of T20.

Kumar - The three fundamentals I mentioned earlier do not exist in T20 cricket. Spinners are trying to bowl quick and waiting for the batsman to make the mistake. The spinner is not trying to make the batsman commit a mistake by sticking to the fundamentals. In four overs you cannot plan and execute.

Shivalkar - They have become defensive. No one offers the loop anymore. The difference has been brought upon by the bowlers themselves. A consistent loop will always check the batsmen, in T20 too, and also get them out. But you have to be deceptive. At times you should deliver from behind the popping crease, but you cannot allow the batsmen to guess that. That allows you more time for the delivery to land, for your flight to dip. The batsman is put in a fix. I have trapped batsmen that way.

Erapalli Prasanna (left), one of India's famed spin quartet, with Padmakar Shivalkar, who took 580 first-class wickets at 19.69 but never played a Test © AFP

Erapalli Prasanna (left), one of India's famed spin quartet, with Padmakar Shivalkar, who took 580 first-class wickets at 19.69 but never played a Test © AFPWe were playing for Tatas against Indian Oil [Corporation] in the Times Shield. Dilip Vengsarkar was standing at short extra cover. One batsman stepped out, trying to drive me, but Dilip took an easy catch. A couple of overs later he took another catch at the same spot. A third batsman departed in similar fashion in quick succession. Then a lower-order batsman played straight to Dilip, who dropped the catch as he was laughing at the ease with which I was getting the wickets. "Paddy, in my life I have never taken such easy catches," Dilip said, chuckling. The batsmen were not aware I was bowling from behind the crease. If they had noticed, they might have blocked it.

What is the one thing you cannot teach a spinner?

Goel- Practice. Line, length and control can only be gained through a lot of hard practice. No one can teach that. Spin bowling is a natural talent. Every ball you have to think as a spinner - what you bowl, how you try and counter the strength or weakness of a batsman, read his reactions, whether he plays flight well and then I need to increase my pace, and such things. All these subtle things only come through practice.

Kumar - There is no such thing that cannot be taught.

Shivalkar - This game is a play of andaaz [style]. That andaaz can only be learned with experience.

What are the things that every spinner needs to have in his toolkit?

Goel - Firstly, you have to check where the batsman plays well, so you don't pitch it in his area. Don't feed to his strengths. You have to guess this quickly.

"It was Subhash Gupte's ability to adjust and adapt on any kind of surface, his perseverance and the variety he had - my goodness, no one came near to him!"

VV KUMAR

Kumar - A spinner should understand what line and length is before going into a match.

Shivalkar- You have to decide that on your own. What I have, what can I do are things only a spinner needs to understand on his own. For example, a batsman cuts me. Next time he tries, I push the ball in fast, getting him caught at the wicket or bowled.

Goel- Practice. Line, length and control can only be gained through a lot of hard practice. No one can teach that. Spin bowling is a natural talent. Every ball you have to think as a spinner - what you bowl, how you try and counter the strength or weakness of a batsman, read his reactions, whether he plays flight well and then I need to increase my pace, and such things. All these subtle things only come through practice.

Kumar - There is no such thing that cannot be taught.

Shivalkar - This game is a play of andaaz [style]. That andaaz can only be learned with experience.

What are the things that every spinner needs to have in his toolkit?

Goel - Firstly, you have to check where the batsman plays well, so you don't pitch it in his area. Don't feed to his strengths. You have to guess this quickly.

"It was Subhash Gupte's ability to adjust and adapt on any kind of surface, his perseverance and the variety he had - my goodness, no one came near to him!"

VV KUMAR

Kumar - A spinner should understand what line and length is before going into a match.

Shivalkar- You have to decide that on your own. What I have, what can I do are things only a spinner needs to understand on his own. For example, a batsman cuts me. Next time he tries, I push the ball in fast, getting him caught at the wicket or bowled.

What is beautiful about spin bowling?

Goel - When the ball takes a lot of turn and then goes on to beat the bat - it is beautiful.

Kumar - A spinner has a lot of tools to befuddle the batsman with and be a nuisance to him at all times. He has plenty in his repertoire, which make him satisfying to watch as well as make spin bowling a spectacle.

Shivalkar - When you get your loop right, the best batsman gets trapped. You take satisfaction from the fact that the ball might have dipped, pitched, taken the turn, and then, probably, turned in or out to beat the batsman. You can then say "Wah". You have Vishy facing you. You assess what he is doing and accordingly set the trap.

Goel - When the ball takes a lot of turn and then goes on to beat the bat - it is beautiful.

Kumar - A spinner has a lot of tools to befuddle the batsman with and be a nuisance to him at all times. He has plenty in his repertoire, which make him satisfying to watch as well as make spin bowling a spectacle.

Shivalkar - When you get your loop right, the best batsman gets trapped. You take satisfaction from the fact that the ball might have dipped, pitched, taken the turn, and then, probably, turned in or out to beat the batsman. You can then say "Wah". You have Vishy facing you. You assess what he is doing and accordingly set the trap.

Monday, 27 February 2017

How I learnt to (nearly) bowl the doosra

Ashley Mallett in Cricinfo

The final day of the South Australia versus West Indies match was supposed to be a red-letter day for the local spin twins, offie Ashley Mallett and leggie Terry Jenner. Opener Ashley "Splinter" Woodcock was standing in for our captain, Ian Chappell, and Splinter told all and sundry in the media overnight that the spinners would take his team to victory.

It was December 23, 1975. West Indies had scored just 188 and we had declared with eight down for 419. Not all went to plan in Splinter's spin strategy, though, for neither TJ nor I got a bowl before lunch and had to wait an hour to get on in the middle session.

I got left-hander Roy Fredericks caught at first slip by Gary Cosier, who rarely hung on to one in that position. Then I found myself trying to breach the seemingly impenetrable defence of the two incumbents enjoying a good fourth-wicket stand: Viv Richards and Lawrence Rowe. I vividly recall bowling two ordinary offies to Rowe, which he dismissed with all the energy and obvious joy of a headmaster whacking you with a full swipe of his cane.

It was then I hit on the idea of doing what I used to do as a youngster when my offbreaks were off the radar; I decided to bowl a legbreak.

The ball left in a song of spin, a fluttering-buzzing sound to gladden the ear. As it made its way towards the relaxed Rowe, it curved slightly to the leg side. I figured he would pick the change from my hand, but that didn't matter. He still had to play it. As it turned out, the ball landed in a bit of rough outside leg stump, Rowe attempted to sweep, missed the ball entirely, and it crept round the back of his legs, hitting middle and off stumps with just enough force to dislodge a bail.

TJ was at first slip and I waltzed down the pitch, spinning leggies from hand to hand, and said: "Mate, this legspin caper is a breeze. I think I'll stop right now."

And indeed, I never bowled another leggie in international cricket. Maybe I should have done.

----Also read

Leg spin Q & A from Warne's coach

On Walking - Advice for a Fifteen Year Old

The final day of the South Australia versus West Indies match was supposed to be a red-letter day for the local spin twins, offie Ashley Mallett and leggie Terry Jenner. Opener Ashley "Splinter" Woodcock was standing in for our captain, Ian Chappell, and Splinter told all and sundry in the media overnight that the spinners would take his team to victory.

It was December 23, 1975. West Indies had scored just 188 and we had declared with eight down for 419. Not all went to plan in Splinter's spin strategy, though, for neither TJ nor I got a bowl before lunch and had to wait an hour to get on in the middle session.