'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label warne. Show all posts

Showing posts with label warne. Show all posts

Monday, 18 February 2019

Sunday, 25 November 2018

Friday, 26 October 2018

Saturday, 26 November 2016

Warne and Jayawardene Tutorial on Bowling Spin and Batting against Spin

Warne and Jayawardene on Bowling and Battling Spin

Sunday, 24 May 2015

Arjuna Ranatunga - Large and in charge

Defiant, passionate, cunning - Arjuna Ranatunga was a mighty tough cookie on the field and an unwavering friend off it

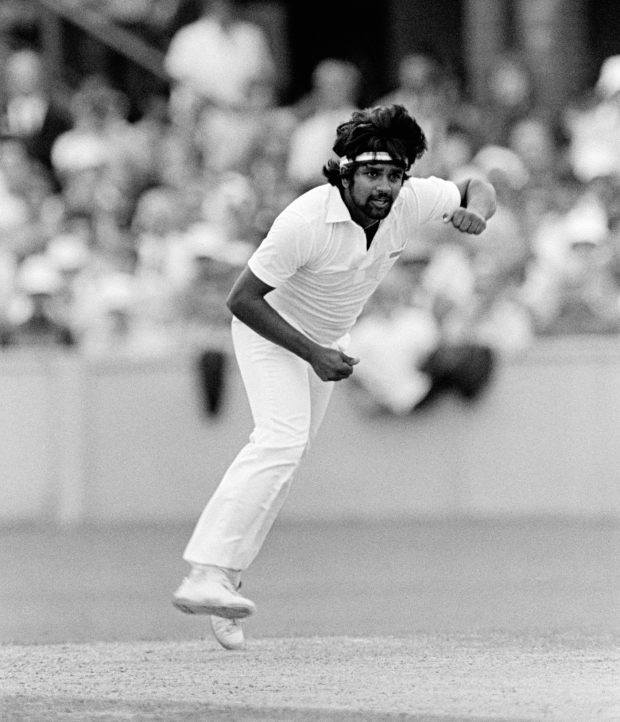

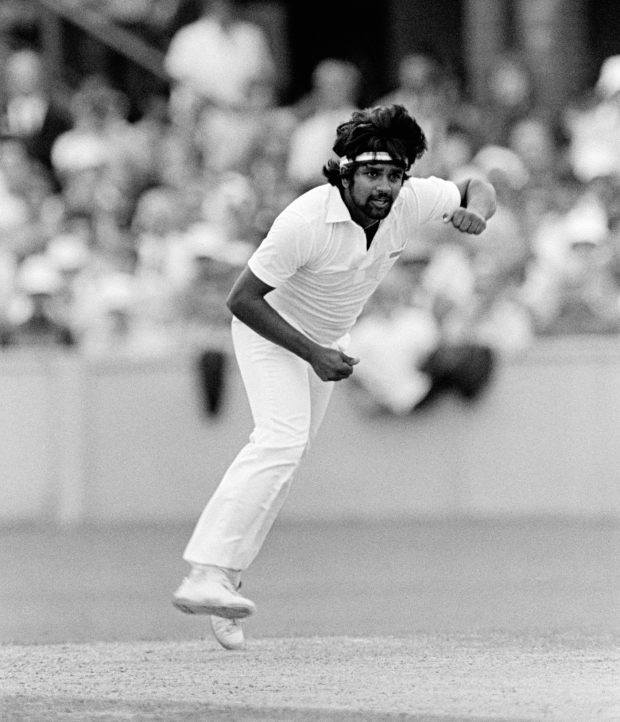

A streamlined Arjuna bowls in the 1983 World Cup © Getty Images

On the eve of the World Cup final he told the many drooling media hounds that Shane Warne was just an average bowler. It caused a violent reaction, more so because "Chef" had been pecking away at the Aussie psyche for a few years and this was the ultimate insult. While Warne tightened with fury, Aravinda de Silva - Arjuna's right-hand man and master batsman - loosened up. Two buttons pressed, both for different purposes, both pushed to achieve one result.

Arjuna dabbed the winning run down to his favourite third-man area. Upon seeing it disappear to the boundary, he reached down and grabbed a stump. It was as if he were picking up the stake he had earlier rammed in the ground upon his arrival. That stake stood for a nation that had cracked the code to win a world title. Ranatunga's name was etched in history forever.

We became close companions off the field. He would take me home to dinner, offering his favourite foods and delights. Not surprisingly, he enjoyed a fine feast, probably more than he did cricket, and I loved hanging out with someone so at ease. He also helped me get expert treatment for my ailing legs, so I could get fit again after developing hamstring problems due to my knee condition. He took me to places I never knew existed, and I felt safer with him in a foreign land than I did in any other.

Arjuna wasn't really an arch-enemy or a player I loved to hate. I loved him, full stop. Mostly I loved the way he stood up to the big boys, the bullies, and bulldozed them back in his unique inspiring way. He represented the underdog.

Arjuna left everything out on the park and, going by his healthy waistline, that was quite a plateful.

MARTIN CROWE in Cricinfo MAY 2015

Truth be known, I love to hate the Australians more than anyone else. And therefore the man who got under their skin the most is my hero. Appearances can be deceiving, and when it comes to Arjuna Ranatunga, the rotund Sri Lankan mastermind, there was nothing soft in his underbelly. He is as tough a cricketer as I have ever come across.

We represented our countries at the same time, both very young, eager allrounders hoping to fit into the cut and thrust of international cricket. Sri Lanka were just beginning their climb, possessing many fine cricketers, if not hardened professionals. New Zealand were a nice mix of amateur and professional, led in example by the pro's pro, Richard Hadlee.

I first spoke to Arjuna while fielding under a helmet at short legin Kandy in 1984. He was defiantly chirpy at the crease, never taking a backward step. His game was a bit limited - the cut and sweep were his release shots. He appeared unfit, yet he never lacked for effort or punch. He quickly became known as "Chef": hungry, dressed in white, and ready to give hell to anyone who didn't conform to the rules of his workspace.

We teased each other a little but deep down we had huge respect for one another, and I loved his smile and zest for life. He had no out-of-control ego, or fear, just a massive heart and a cunning mind. Despite Sri Lanka having no experience as such, Arjuna soaked up all he could. It was as if it was preordained - his apprenticeship was a natural platform for him to learn how to mastermind his team to unprecedented glory.

He quickly became known as "Chef": hungry, dressed in white, and ready to give hell to anyone who didn't conform to the rules of his workspace

I was more comfortable bowling to Arjuna than batting against him. I could swing it away from him, and enjoyed following up my bouncers with a prolonged look to see his response. He was always muttering something and smiling. When he bowled to me, he knew I feared getting out to his miserable deflated wobblies.

Regrettably, he dismissed me too often, notably in Wellington, when I was one short of being the first Kiwi to post a triple-century. I recall the moment when he got to the end of his run-up, beaming ear to ear. He had a gift for me. At that precise moment, up popped the thought that I had already achieved the triple-century. I didn't remove the thought; instead, I hung on to the feeling a bit longer. "Heck, you've done it," I muttered.

Arjuna rolled in and offered up a juicy half-volley wide of off stump. It was a glorious finish to a hard-fought draw, and some history. I never saw the ball leave his hand. My mind was scrambled as I jumped from "Done it", to "Where is it?" Seeing it very late and very wide, I lashed out in desperation, the blade slicing the ball and sending a thick edge into the slip cordon. Hashan Tillakaratne, the wicketkeeper, moved swiftly and calmly to his right and plucked the ball millimetres from the ground.

While Arjuna was upset for me, I was angry and inconsolable. A couple of weeks later, in the Hamilton Test, he dealt it to me again with the same mode of dismissal. Unintentionally, he had got under my skin, in the nicest possible way. I began to hate facing his gentle floating autumn leaves.

By 1996 he was a wise sage. He knew his team and their strengths, and he knew what buttons needed pushing. He saw the Australians as an easy target. He saw how false they could be: loud, lippy banter masking their own fears, often turning into personal abuse when the pressure mounted. He believed the more they resorted to mental disintegration the more they exposed themselves, diverting their attention from their obvious skill and from the job at hand.

Truth be known, I love to hate the Australians more than anyone else. And therefore the man who got under their skin the most is my hero. Appearances can be deceiving, and when it comes to Arjuna Ranatunga, the rotund Sri Lankan mastermind, there was nothing soft in his underbelly. He is as tough a cricketer as I have ever come across.

We represented our countries at the same time, both very young, eager allrounders hoping to fit into the cut and thrust of international cricket. Sri Lanka were just beginning their climb, possessing many fine cricketers, if not hardened professionals. New Zealand were a nice mix of amateur and professional, led in example by the pro's pro, Richard Hadlee.

I first spoke to Arjuna while fielding under a helmet at short legin Kandy in 1984. He was defiantly chirpy at the crease, never taking a backward step. His game was a bit limited - the cut and sweep were his release shots. He appeared unfit, yet he never lacked for effort or punch. He quickly became known as "Chef": hungry, dressed in white, and ready to give hell to anyone who didn't conform to the rules of his workspace.

We teased each other a little but deep down we had huge respect for one another, and I loved his smile and zest for life. He had no out-of-control ego, or fear, just a massive heart and a cunning mind. Despite Sri Lanka having no experience as such, Arjuna soaked up all he could. It was as if it was preordained - his apprenticeship was a natural platform for him to learn how to mastermind his team to unprecedented glory.

He quickly became known as "Chef": hungry, dressed in white, and ready to give hell to anyone who didn't conform to the rules of his workspace

I was more comfortable bowling to Arjuna than batting against him. I could swing it away from him, and enjoyed following up my bouncers with a prolonged look to see his response. He was always muttering something and smiling. When he bowled to me, he knew I feared getting out to his miserable deflated wobblies.

Regrettably, he dismissed me too often, notably in Wellington, when I was one short of being the first Kiwi to post a triple-century. I recall the moment when he got to the end of his run-up, beaming ear to ear. He had a gift for me. At that precise moment, up popped the thought that I had already achieved the triple-century. I didn't remove the thought; instead, I hung on to the feeling a bit longer. "Heck, you've done it," I muttered.

Arjuna rolled in and offered up a juicy half-volley wide of off stump. It was a glorious finish to a hard-fought draw, and some history. I never saw the ball leave his hand. My mind was scrambled as I jumped from "Done it", to "Where is it?" Seeing it very late and very wide, I lashed out in desperation, the blade slicing the ball and sending a thick edge into the slip cordon. Hashan Tillakaratne, the wicketkeeper, moved swiftly and calmly to his right and plucked the ball millimetres from the ground.

While Arjuna was upset for me, I was angry and inconsolable. A couple of weeks later, in the Hamilton Test, he dealt it to me again with the same mode of dismissal. Unintentionally, he had got under my skin, in the nicest possible way. I began to hate facing his gentle floating autumn leaves.

By 1996 he was a wise sage. He knew his team and their strengths, and he knew what buttons needed pushing. He saw the Australians as an easy target. He saw how false they could be: loud, lippy banter masking their own fears, often turning into personal abuse when the pressure mounted. He believed the more they resorted to mental disintegration the more they exposed themselves, diverting their attention from their obvious skill and from the job at hand.

A streamlined Arjuna bowls in the 1983 World Cup © Getty Images

On the eve of the World Cup final he told the many drooling media hounds that Shane Warne was just an average bowler. It caused a violent reaction, more so because "Chef" had been pecking away at the Aussie psyche for a few years and this was the ultimate insult. While Warne tightened with fury, Aravinda de Silva - Arjuna's right-hand man and master batsman - loosened up. Two buttons pressed, both for different purposes, both pushed to achieve one result.

Arjuna dabbed the winning run down to his favourite third-man area. Upon seeing it disappear to the boundary, he reached down and grabbed a stump. It was as if he were picking up the stake he had earlier rammed in the ground upon his arrival. That stake stood for a nation that had cracked the code to win a world title. Ranatunga's name was etched in history forever.

We became close companions off the field. He would take me home to dinner, offering his favourite foods and delights. Not surprisingly, he enjoyed a fine feast, probably more than he did cricket, and I loved hanging out with someone so at ease. He also helped me get expert treatment for my ailing legs, so I could get fit again after developing hamstring problems due to my knee condition. He took me to places I never knew existed, and I felt safer with him in a foreign land than I did in any other.

Arjuna wasn't really an arch-enemy or a player I loved to hate. I loved him, full stop. Mostly I loved the way he stood up to the big boys, the bullies, and bulldozed them back in his unique inspiring way. He represented the underdog.

Arjuna left everything out on the park and, going by his healthy waistline, that was quite a plateful.

Tuesday, 10 February 2015

Cricket, Poker, Luck and Skill

Chris Bradshaw in Wisden India

About the only thing that the Rio Casino in Las Vegas has in common with Lord’s is that it attracts a disproportionate number of men with a liking for bright red trousers. Superficially, there’s little in common between the home of the World Series of Poker and cricket’s traditional headquarters. Dig a little deeper though and there is a surprising amount that cricketers, and especially captains, can learn from their poker-playing counterparts.

Richie Benaud famously said: “Captaincy is 90 per cent luck, only 10 per cent skill – but don’t try it without the 10 per cent.” Despite being more of a horse-racing man than a card sharp (Benaud restricts himself to wagers on things that cannot speak), his adage sounds remarkably similar to something written by Doyle Brunson, one of the greatest poker players who has ever lived.

In his best-selling 1978 strategy book Super System: A Course In Power Poker, the two-time World Series of Poker Main Event winner wrote: “Poker is more art than science, that’s what makes it so difficult to master. Knowing what to do – the science – is about 10 per cent of the game. Knowing how to do it – the art – is the other 90 per cent.” Not identical to Benaud’s line but near enough to warrant a closer look.

Poker players loosely fit into two main playing styles. Tight players proceed cautiously and wait for the best hands. Loose players will play with any two cards. Taken to its extreme, a super-tight player would only play a pair of aces while a hyper-loose player would try his luck with anything, even 7-2 off suit, the worst starting hand in Texas hold ’em. Allied to the tight and loose tendencies are levels of aggression. Aggressive players are always on the front foot, looking to attack, while passive players tend to fear losing rather than trying to win.

In the long run, both tight and loose aggressive poker players can be successful. It’s possible, but much harder, for tight passive types to make much money. Loose passive players might as well set fire to their bankroll.

Those tendencies are often clearly visible on the cricket pitch. A tight captain will wait until he has a ridiculous lead before setting a declaration while a looser leader would dangle a carrot. Andrew Strauss was a prime example of a tight, aggressive captain. The commentary box moaners may not have liked his seemingly defensive fields but by employing a sweeper early in the innings – rather than having an extra slip, say – Strauss preferred to retain control rather than speculate. When and only when, the game was in his team’s favour would Strauss go on the attack.

Brendon McCullum, on the other hand, is much more akin to the loose aggressive poker player and willing to have a gamble. If he sets an attacking field and the ball flies through the vacant cover region to the boundary, so what? An unorthodox bowling change may mean conceding a few runs but it might also pick up a wicket. If the rewards are big enough, he’ll follow that hunch even if the results are costly if he’s proved wrong.

The flip side of that aggressive stance can be seen in any number of delayed England declarations and botched run chases. Take the home side’s 2001 capitulation to Pakistan at Old Trafford. Alec Stewart’s side went from tight aggressive to tight passive with disastrous results. With the score at 174 for one and needing another 196 runs from 45 overs for a famous victory, England lost a wicket then shut up shop. Instead of going for the win, they tried not to lose. One session and eight wickets later, Waqar Younis and co had tied the series.

***

The stereotype of the poker player as a fast-talking, cigar-chomping, road gambler is an outdated one. You’re far more likely to see a softly spoken Scandinavian wearing headphones and a hoodie in a top tournament these days rather than a Stetson-wearing Texan. Technology has transformed poker and the statistically-minded are in the ascendancy.

Virtually every professional poker player now uses a database to log every raise, every bet size, every fold, every call, every unexpected all-in move and just about everything else that happens at the online tables. Crunching the numbers to identify opposition weaknesses and their own technical deficiencies has become a crucial weapon for even semi-serious players of the game.

Cricket’s own statistical revolution has mirrored the one undergone by poker. Every delivery is tracked by an analyst, every shot monitored by a specialist coach and every potential technical frailty probed by the team’s brain trust. The captains in the Sky commentary box (what is the collective noun for a group of England captains? A disappointment? A grumble?) may say that a third man should be in place. The figures in black and white suggest otherwise.

Of course it’s all well and good for a team to have a plethora of stats at their disposal, but if they don’t know how to use them it can cause more confusion than clarity. Despite enjoying some recent success, England have been accused of producing teams full of cricketing automatons, unable to think on their feet or adapt in the face of changing circumstances. If the plan discussed in the dressing-room isn’t working, England’s C-3POs have often seemed too rigid to do anything about it. “The stats said we should bounce them out. We’ll carry on bouncing them, even though the ball is disappearing to the boundary twice an over.”

A good captain, like a good poker player, will use the stats but won’t be a slave to them. He will still trust his feel for the game to assess the strengths and weaknesses of his opponent.

The concept of pot odds is also one that is easily transferable to cricket. A poker player may have to pay to chase his straight or flush draw but if the odds are right, it becomes a mathematically correct move to make. It’s a risk, but in the long run the rewards justify taking that chance. Similarly, a bowler might dish up three half volleys, knowing that they’ll likely be despatched through an extra-cover region deliberately left vacant. The fourth delivery, a fraction shorter and a touch wider, gets nicked and is pouched by the slip fielder who could have been patrolling the covers. The bowler may have given up a few extra runs but has been rewarded with a wicket. A good poker player knows when to take a gamble as if he hits his outs, he’ll make a big profit. A cricket captain should be able to do the same.

“Play aggressively, it’s the winning way,” Brunson writes. Being aggressive isn’t a call to suddenly awaken your inner Merv and start mouthing off at the competition. It simply means taking control and dictating terms. “Timid players don’t win in high-stakes poker.” They rarely win at cricket either.

It sounds obvious but the great captains, like the best poker players, are always thinking one move ahead of their opponent. A successful poker player will recognise when to adapt as the conditions of the game alter. The arrival of a deep-stacked, ultra-loose player can completely change the dynamics of a table, just as a big-hitting tail-ender can totally change the momentum in cricket. An intuitive captain will know when to attack and when to hang back and wait for a more profitable opportunity. “Changing gears is one of the most important parts of playing poker. It means shifting from loose to tight play and vice versa,” writes Brunson.

Andrew Strauss was a prime example of a tight, aggressive captain – who would wait until he has a ridiculous lead before setting a declaration. © Getty Images

The same is true of players going on a hot streak and winning a number of pots in quick succession. “Your momentum is clear to all players. On occasions like this you’re going to make correct decisions and your opponents may make errors because they are psychologically affected by your rush.” Brunson could be writing about any captain whose side has inflicted a crippling batting collapse on the opposition.

To succeed, “you’ll need to get inside your opponent’s head,” writes Brunson. In the modern game, there has been no better exponent of this than Shane Warne (just ask poor Daryl Cullinan). Being able to turn a leg-break a yard was famously Warne’s greatest asset. His mastery of the dark arts of mental disintegration helped shape the aura that accompanied him wherever he played though, especially against England. Before every series there was talk of a new mystery delivery. The zooter, the clipper, whatever you want to call it. The new phantom ball rarely appeared but the seed had been planted, the trap set, the bluff laid. And Warne was ready to collect.

Of course a cricket skipper can utilise the team members he has at his disposal while a poker player rides solo. For Steve Waugh, having Shane Warne and Glenn McGrath in his side was like being dealt aces every hand. Aces make you a favourite, but they do get cracked if they’re not handled properly. Poker players are dealt duff hands most of the time. The best players get the best out of what they’ve been given.

Even though he’s now in his eighties, Brunson still manages to play in some of the biggest cash games around, with thousands of dollars at stake. Successful “old-school” players have welcomed the way the game has changed and adapted accordingly (you won’t hear a Truemanesque “I don’t know what’s going off out there” from Brunson). Like cricketing tactics, poker techniques have evolved over time. If Brunson played the same way now as he did when he won his first world title in 1976 he’d be eaten alive by the twentysomething maths geeks. The basic philosophies outlined in Super System still hold true though. The precise tactics may have changed but the instincts that served him so well at the start of his career continue to do so today.

The poker world these days is peppered with current and former sporting greats. Footballers Tony Cascarino and Teddy Sheringham have earned six-figure paydays on the tournament circuit. Rafa Nadal and Boris Becker act as ambassadors for a major online poker site. Given the storm surrounding match-rigging and spot-fixing, it’s probably understandable that most cricketers have steered clear. The obvious exception is Shane Warne, who regularly clears a couple of weeks from his commentary schedule to play at the World Series of Poker.

In a brief stint as captain of Australia’s one-day side Warne enjoyed great success, winning 10 out of 11 matches. The same formula brought IPL glory to the Rajasthan Royals and promotion and one-day success to Hampshire.

Ian Chappell once wrote that the leg-spinner who most resembled Warne was the feisty Australian Bill “Tiger” O’Reilly, a man who openly hated batsmen. “He thought they were trying to take the food out of his mouth and consequently he was ultra-aggressive in his efforts to rid himself of the competition,” wrote Chappell. “Warne had a similar thought process and he was constantly plotting the batsman’s downfall.” Sounds like ideal card-room strategy. It’s no wonder Warne’s now a pretty good poker player.

Mike Brearley’s The Art of Captaincy is usually the first book off the shelf for budding skippers. Potential leaders could do worse than making Super System their second.

Thursday, 3 July 2014

On Cricket Commentary - WHY CONTEXT MATTERS

| Mukul Kesavan in The Telegraph | |

The idea that we should respond to cricketers in purely cricketing terms is a piety that cripples commentary on the game. Cricket commentary’s organizing conceit — that at every turn in a Test there is a technically optimal choice to be made — produces formalist bromides that explain neither the course of the match nor the performances of its main characters.

A good example of the technicist fallacy was Michael Holding’s criticism of Sri Lankan bowling tactics during the second innings of the second Test at Headingley. The Sri Lankan pacemen were bowling short at Joe Root (picture) who wasn’t comfortable. He was hit on the splice, on his gloves, on the body which encouraged the Sri Lankans to work him over for about half an hour. This provoked Holding into Fast Bowling Piety One: bowling short is all very well but you have to pitch it up to take wickets.

Coming from Holding, one of the great West Indian quartet that unnerved a generation of batsmen with scarily fast and lethally short bowling, this was greeted in the Sky commentary box with general hilarity. Holding insisted that the tales of West Indian bouncer barrages were overstated and offered as proof the number of batsmen who were out lbw or bowled. Botham, from the back of the box offered an explanation: the balls must have ricocheted off their faces on to the stumps.

Nasser Hussain spoke up to make the point that Joe Root seemed to have provoked the Sri Lankans while they were batting, and they, in turn had decided to see if they could sledge and bounce him into submission. Given Root’s visible discomfort, Hussain argued that a short burst of intimidatory bowling was a reasonable tactic.

In response Holding produced his clinching cautionary tale: opposing fast bowlers once peppered Michael Clarke with short balls and he ducked and weaved and got hit but he had the last laugh by scoring more than 150 runs in that innings. Middle-aged desis recalled a very different precedent: the 1976 Test in Sabina Park where the West Indian pace attack led by Holding hospitalized three top order Indian batsmen with a round-the-wicket bouncer barrage and battered Bedi’s hapless team into surrendering a match with five wickets standing because the batsmen who weren’t injured were terrified.

Holding was a member of the West Indian team that ruthlessly ‘blackwashed’ England after Tony Greig stupidly provoked the West Indians by promising to make them grovel. His inability to see that Mathews’s targeting of Root was a symptom of an angry team’s determination not to take a step back was a sign of how completely the conventions of cricket commentary can distract intelligent commentators from the real contest unfolding in front of them.

Sri Lankan teams have long felt slighted by the ECB’s habit of offering them stub series or one-off Tests early in the English season. They have been treated like poor relations and this time round they felt not just patronized but persecuted by the reporting of Sachithra Senanayake’s bowling action during the ODI contests that preceded the two-Test ‘series’. It was this sense of being hard done by, this collective determination to be hard men, not game losers that played a part in Senanayake’s Mankading of Jos Buttler, in Angelo Mathews’s refusal to withdraw Senanayake’s appeal and in the public support that Sangakkara and Jayawardene gave Senanayake when Cook and Co. threw a hissy fit afterwards. And it was this keenness to give as good as they got that spurred the Sri Lankan captain to go after Joe Root who had been noticeably chirpy in the field.

That passage of play, with the Sri Lankans bouncing and sledging Root and Root battling it out, was the series summed up in half a dozen riveting overs. This is not to argue that short pitched bowling is more effective than pitched up bowling when it comes to taking wickets: merely to suggest that producing axiomatic pieties as a commentator without accounting for context is pointless.

If Mathews had persisted with a failed tactic over the best part of the day as Cook did when Mathews and Herath were building their rearguard action, Holding might have had a case. But he didn’t, so Holding’s inability to recognize that this spell of short pitched hostility was a flashpoint in this two Test struggle for superiority is a good example of the way in which orthodox nostrums glide over the action they are meant to illuminate.

It wasn’t just Holding who lost the plot in the Sky commentary box, so did David Lloyd. When Mathews began sledging Root and, in spite of remonstrating umpires, calmly carried on sledging Root, a historically minded commentator might have seen him as a worthy heir to Arjuna Ranatunga, that smiling, pudgy, implacable eyeballer of umpires, winder-upper of oppositions and, by some distance, Sri Lanka’s greatest captain.

But all Bumble saw was a captain who, because he was sledging Root, had lost focus and lost control of the match. So what for the rest of the world was a spell of purposeful hostility with Mathews testing Root’s will to survive, was for Lloyd, a failure by the Sri Lankan captain to focus on his main job, thinking Root out.

Just as Mathews’s sledging was read without context, the larger contest between England and Sri Lanka went unframed. On the one hand there was the English team backed up by a prosperous, hyper-organized cricket board which surrounded its Test team with a support staff so large that journalists joked about it, and on the other there was a Sri Lankan team at war with its board, whose players frequently went unpaid and whose principal spinner, Rangana Herath, had to apply for leave from his day job before going on tour. I learnt more about the Sri Lankan team from one brilliant set of vignettes on Cricinfo (“The Pearl and the Bank Clerk” by Jarrod Kimber) than I did through 10 days of Test match commentary.

Do television commentators do any homework? Are they interested in the individuals in the middle or are the players they describe just interchangeable names on some Platonic team sheet? Virtually every commentator in the world is now a distinguished ex-cricketer; are these retired champions meant to embody totemic authority, to exude experience into a microphone, or should they pull information and insight together to tell us something that we can’t see or don’t know already?

One answer to that leading question might be that ball-by-ball commentary has, by definition, a narrow remit. The answer to that, of course, is that you can’t take a form that originated with radio where the commentator had to literally describe the action in the middle and transfer it to a different medium without redefining it.

Sky Sports’s stab at redefinition consists of more graphical information. We have pitch maps and batting wagon wheels which are useful, but surely the rev counter on the top right hand corner of the screen is an answer looking for a question. Does the fact that Moeen Ali gets more revs on the ball than Rangana Herath does make him the better spinner? Sky’s little dial seems to think so.

The best human insights on the Sri Lankan-England series came from Shane Warne and he wasn’t even in the commentary box. The series cruelly confirmed his criticisms of Alastair Cook’s captaincy: having moaned about Warne’s unfairness and huffed about Buttler’s Mankading, Cook led his team to defeat with all the grit of a passive-aggressive Boy Scout.

In the Sky box, we had Mike Atherton who earned a 2.1 in history at Cambridge but you wouldn’t known it from his commentary: he was as indifferent to time and context as his fellow commentators. Ian Botham was, as always, the Sunil Gavaskar of English commentary while the point of Andrew Strauss’s strangled maunderings escaped foreigners in the absence of subtitles.

The one exception to the tedium of Sky commentary was Nasser Hussain simply because he was alert to the politics of a cricket match, to the personal and collective frictions that makes Test cricket the larger-than-life contest that, at its best, it sometimes is. I like to think that the reason for this is that he’s called Nasser Hussain and has an Indian father and an English mother so he can’t pretend that cricket is a self-contained country.

Pace Holding, the rehearsal of textbook orthodoxy might be a necessary part of cricket commentary, but it ought to be a baseline on which good commentators improvise, rather like the tanpura drone that provides soloists with an anchoring pitch. Too often, though, cricket commentary amounts to just the drone without context, insight or information.

If English commentators are frustratingly literal and narrow, their Indian counterparts make Holding and Co. sound like John Arlott channelling C.L.R. James. Policed by the BCCI, desi commentators are so mindful of their contractual obligations and so formulaic in their utterances that they could be replaced by bots without anyone noticing.

Watching a cricket match glossed by the BCCI’s Own, is unnervingly like playing the FIFA video game with automated commentary, where software produces the appropriate cliché whenever the onscreen action supplies the necessary visual cues.

Readymade words for virtual football are bad enough but canned commentary on real cricket needs a special place in hell. Tracer bullets, kitchen sinks, cliff hangers, pressure cookers, sensible cricket, best played from the non-striker’s end, give the bowler the first half hour, leg-and-leg… it never stops, and its petrifying banality turns live cricket into lead. With five Tests to play, this is going to be a long, hot summer. Welcome to purgatory.

|

Tuesday, 20 May 2014

How much talent does the difficult player need?

Exceptionally gifted but unreliable players are often given lots of rope by management, but far too many seem to believe themselves to be deserving of that leeway

Ed Smith

May 20, 2014

| |||

It's been a mixed week for sportsmen out of love with the authorities. Michael Carberry, overlooked after the Ashes tour, publicly stated his frustrations about a lack of communication from the selectors. Many assumed that Carberry, aged 33, had signed his own death warrant and would never play for England again. But the selectors have made a shrewd decision in recalling him. He is a decent, understated man; the England management now looks magnanimous in overlooking a few surprising quotes in a newspaper.

No such luck for Samir Nasri, the wonderfully gifted but moody French footballer. He has been left out of France's World Cup squad. France's coach, Didier Deschamps, explained his decision with bracing honesty: "He's a regular starter at Manchester City. That's not the case today with the France team. And he also said he's not happy when he's a substitute. I can tell you that you can feel it in the squad." Deschamps went further, anticipating his critics by conceding that Nasri was more talented than some players he had selected: "It's not necessarily the 23 best French players, but it's the best squad in my eyes to go as far as possible in this competition."

Talent v unity: an old story.

Rugby union, though, has also brought two mavericks back into the fold. Gavin Henson, Wales' troubled but mercurial playmaker, looks set to return to the red jersey. And England's Danny Cipriani, another flair player who has never found a happy home wearing national colours, has been thrown a lifeline. A last chance that both Henson and Cipriani cannot afford to miss? I bet they have heard that before. And then been handed just one final, last chance. That's often the way with rare talent: different rules apply.

As always, these debates have generally descended into an argument about abstract principles. Pundits have rushed to say that French football has a problem with finding a home for left-field characters. Other have bridled at Deschamps' logic: who should be happy being put on the bench anyway? It is the job of managers, we are often told, to finesse and handle talented but unconventional personalities. Indeed, with a moment's reflection, anyone can produce a list of world-beating players who didn't conform to a coach's template for a model professional - from Diego Maradona to Andrew Flintoff.

Such a list, sadly, proves absolutely nothing. Because it is just as easy to find examples of teams that began a winning streak by leaving out a talented but unreliable star player. The French team that won the World Cup in 1998 left out both David Ginola and Eric Cantona, just as the current side have now omitted Nasri.

In the popular imagination, the argument about dropping and recalling star players revolves around the juicy, gossipy questions: how difficult are they, how does their awkwardness manifest itself, has anyone tried to talk them round? This is naturally intriguing stuff. But the other half of the question - the crucial half - is too often ignored. Quite simply, how much better are they than the next guy?

| When mavericks slide from outright brilliance to mere high competence they find patience runs out alarmingly quickly. There is a lot of high competence around. It is replaceable. Not so genuine brilliance | |||

If you are a lot better, it is amazing how forgiving sports teams can be. Luis Suarez was banned for eight games for racially abusing Patrice Evra. He then served another ten-match ban for biting a Chelsea player. Obviously Liverpool sacked him instantly on the grounds that he was bringing the club into disrepute and becoming a distraction from the task of winning football matches? No, they didn't do anything of the kind. They calculated that Suarez was the best chance, their only chance, of mounting a challenge for trophies. If Suarez had been Liverpool's sixth- or seventh-best player, rather than their star man, he would have been kicked out years ago.

In other words, the best protection from being dropped for being "difficult" is to be brilliant. Even as a young man, England midfielder Paul Gascoigne was a heavy drinker and an unreliable man. But he was a sensational footballer. Coaches put up with him because they calculated it was in their own and the team's rational self-interest. By the latter stages of his career, Gascoigne was still a heavy drinker and an unreliable man, but he was now only occasionally an excellent footballer. Glenn Hoddle felt Gascoigne was too unfit to play at the 1998 World Cup. The glass was half-empty.

When mavericks slide from outright brilliance to mere high competence they find patience runs out alarmingly quickly. There is a lot of high competence around. It is replaceable. Not so genuine brilliance. That is why Shane Warne was able to criticise Australia coach John Buchanan and (nearly) always stay in the team. Any rational man who asked himself the question: "Are Australia a better team with Warne in it?" came to the unavoidable conclusion: "Yes, definitely."

Here's the central point. At this exalted level of elite sport, a great number of players have an epic degree of self-belief. Being convinced of their own greatness is an aspect of their magic. They back themselves to shape the match, to determine its destiny - especially the big matches. Instead of seeing themselves as just one of a number of exceptionally talented players, in their own minds they are men apart, special cases.

They aren't always right, though. So the question becomes: how good, how difficult? They are two aspects of the same equation, a calculation that is being made every day by coaches all over the world - on the school pitch, in the reserves squad, all the way to the World Cup final.

A player, too, must make his own calculation. Would pretending to be someone else - a more compliant, easy-going man - centrally detract from my performances? Must I play on my own terms, behaving as I like? But this question must coexist with another, less comfortable one: am I good enough to get away with it?

Not many. Fewer, certainly, than the number who think they can.

Wednesday, 11 September 2013

The red badge of courage

There are several reasons for sporting success but it's possible that bravery exerts the foremost influence

Rob Steen in Cricinfo

September 11, 2013

| |||

Half a century ago, Willie Mays was baseball's Garry Sobers. He ran like the wind, possessed a bone-chilling throw, maintained a sturdy batting average, and biffed home runs by the truckload. A superb centre-fielder, he also claimed the game's most celebrated catch, an over-the-shoulder number in the 1954 World Series that still inspires awe for its athleticism, spatial awareness and geometric precision.

Almost without exception, white New York sportswriters said he was gifted: the inference many drew was that this man, this black man, had succeeded not through hard work but because he had been granted a God-given head start. Even if you somehow manage not to classify this as racism, it remains deeply insulting.

"Gifted" is still shorthand for unfeasibly and unreasonably talented. We use it all the time in all sorts of contexts, mostly enviously. Wittingly or not, the implication is that the giftee has no right to fail. Hence the ludicrous situation wherein David Gower aroused far more scorn than Graham Gooch yet wound up with more Ashes centuries and a higher Test average.

Nature v nurture: has there ever been a more contentious or damaging sociological debate? Its eternal capacity to polarise was borne out last week when the Times devoted a hefty chunk of space to the views of two sporting achievers turned searching sportswriters, Matthew Syed and Ed Smith. Here was a fascinating clash of perspectives, not least since both have recently written books whose titles attest to the not inconsiderable role played by chance: Syed's Bounce and Smith's Luck.

In the red corner sits Syed, a two-time Olympian at table tennis. Referencing the original findings of the cognitive scientist Herbert Simon, winner of the 1978 Nobel Prize, he supported the theory espoused by Malcolm Gladwell, who argued in his recent book Outliers that success in any field only comes about through expertise, which means being willing to put in a minimum of 10,000 hours' practice.

Smith, the former England batsman and Middlesex captain who writes so thoughtfully and eloquently for this site, takes his cue from The Sports Gene: What Makes the Perfect Athlete, a new book by the American journalist and former athlete David Epstein, who takes issue with Gladwell.

Genetic make-up, Epstein concludes, is crucial. Usain Bolt, as he stresses, is freakishly tall for a sprinter. He also cites the example of Donald Thomas, who won the high jump title at the 2007 World Athletics Championships just eight months after taking his first serious leap. The key was an uncommonly long Achilles tendon, which doubled as a giant springboard. Subsequent practice, however, failed to generate any improvement. But if we insist, simplistically, that athletic talent is a gift of nature, counters Syed, echoing academic research, this can wreck resilience. "After all, if you are struggling with an activity, doesn't that mean you lack talent? Shouldn't you give up and try something else?"

The debate is rendered all the more complex, of course, by its prickliest subtext. Having conducted a globetrotting survey of attitudes, one "eye-opener" for Epstein was the reluctance of scientists to publish research on racial differences. Fear of the backlash continues to trump the need for understanding.

| Sport is uniquely taxing because it asks young bodies to do the work of seasoned minds | |||

These delicate issues and stark divergences of opinion, though, mask a deeper, more pertinent and resonant truth. To give nature all the credit is to deny the capacity for change; to plump for nurture is to ignore the inherent unfairness of genetics. Isn't it a matter of nurturing nature? Besides, surely success is more about application. Possessing gallons of ability is no guarantee if, like Chris Lewis, who promised so much for England in the 1990s and delivered conspicuously less, you lack the wherewithal to take full advantage. And if skill was the sole prerequisite, how did Steve Waugh become the game's most indomitable force?

Where would Waugh have been without determination? The same could be asked of the game's two most powerful current captains, MS Dhoni and Michael Clarke. Without that inner drive, would Dhoni have emerged from his Ranchi backwater? Would Clarke have risen from working-class boy to metrosexual man? Ah, but is determination innate or learnt? Cue a cascade of further questions. How telling is environment - social, economic and geographic? Does it have more impact during childhood or adulthood? Is temperament natural or nurtured? Can will be developed? Is confidence instinctive or acquired? I haven't the foggiest. All I can say with any vestige of certainty is that, when preparing a recipe for success, limiting ourselves to a single ingredient seems extraordinarily daft and utterly self-defeating.

So here's another thought. Given that, for the vast majority, achieving sporting success invariably involves battling against at least a couple of odds, surely courage has something to do with it: the courage to overcome prejudice, disadvantage or fear of failure. The courage to perform when thousands are urging you to fail - or, worse, succeed. The courage to take on the bigger man, the better-trained man, to stand your ground, put bones at risk, resist defeatism. The courage not just to be different but act different. The courage not to play the percentages. The courage not to be cautious. The courage to try the unorthodox, the outrageous. The courage to risk humiliation. And the courage, after suffering it, to risk it again.

| |||

The older we get, theoretically at least, the safer we feel and the less courage we need. The less courage I need, the more I admire it in others, hence the growing conviction that bravery exerts the foremost influence on a sportsman's fate, as critical on the field as in the ring or on chicane. In team sports, it is even more imperative: sure, the load can be shared, but it still takes a special type of courage, of nerve, to satisfy the selfish gene - i.e. express yourself - while serving the collective good.

What makes this even more complicated is that when sportsfolk most need courage - between the ages of, say, 14 and 40 - few have fully matured as human beings. How many of the most powerful business leaders or successful lawyers or respected doctors are under 50? How many of the most eminent actors, musicians, authors or chat-show hosts? Sport is uniquely taxing because it asks young bodies to do the work of seasoned minds.

In cricket, the first test of courage comes early. Of all the factors that dissuade wide-eyed schoolboys from pursuing the game professionally, none quite matches the fear of leather and cork. Even for those at the summit, it remains a fear to be acknowledged, tolerated and respected. As Ian Bell recently highlighted when discussing the delights of fielding at short leg, conquest is impossible.

Where the air is rarest and the stakes highest, spiritual courage is even more vital. "I was an outsider. I still am. I didn't do what they wanted." Lou Reed's words they may be, but they could just as easily be the reflections of another couple of performers happy to walk on the wild side, Kevin Pietersen and Shane Warne. That these brothers-in-fitful-charms happen to be 21st-century cricket's foremost salesmen seems far from accidental.

Both are victories for nurture. Both practise(d) with ardour and diligence, mastering their craft, continually honing and refining, then building on it, then honing and refining some more. Both studied opponents assiduously, the better to parry, outwit and confound. Both became inventors, devising daring drives and dastardly deliveries. Yet nature, too, has played a significant role. Both are enthusiasts and positive thinkers. Both radiate self-belief and superiority. Both boast heavenly hand-eye co-ordination. Above all, nonetheless, both aspire(d) to something loftier than mere excellence. Both craved not just to be the best, nor even to dominate, but to astound. To do that takes another very special brand of courage.

For Warne, this meant having the courage to give up one sport and pursue one for which he seemed, physically and temperamentally, far less suited. For Pietersen, it meant having the courage to leave his homeland and to be reviled as both intruder and traitor. Neither, moreover, could completely suppress nature, so they remained true to their gambling instincts and innate showmanship. Without the mental strength to achieve the right balance, such an intricate juggling act would have been beyond them. Perhaps that's what courage really is: the strength to stick to your own path.

Don't take it from me; listen to Bolt: "I'd seen so many people mess up their careers because people had told them what to do and what not to do, almost from the moment their lives had become successful, if not before. The joy had been taken from them. To compensate, they felt the need to take drugs, get drunk every night, or go wild. I realised I had to enjoy myself to stay sane."

Nature versus nurture. Mind versus matter. Means versus ends. Turn those antagonists into protagonists and we might get somewhere. First, though, there must be acceptance: compiling an idiot-proof guide to success is akin to tackling a vat of soup with miniature chopsticks. Besides, if it were easy, there would be more winners than losers. In sport, where success means nothing if nobody fails, that might present a particularly prickly problem.

The best advice? Try Laura Nyro's rallying-cry:

Oh-h, but I'm still mixed up like a teenager

Goin' like the 4th of July

For the sweet sky

Oh-h, but I'm still mixed up like a teenager

Goin' like the 4th of July

For the sweet sky

Wednesday, 16 January 2013

The leggie who was one of us

It's hard not

to admire the story and spirit of a club spinner who believed he would

one day make it to the big leagues - and briefly did

Jarrod Kimber

January 16, 2013

|

|||

I grew up in the People's Democratic Republic of Victoria. I was

indoctrinated early. Dean Jones was better than Viv Richards in

Victoria, and had a bigger ego as well. Darren Berry kept wicket with

the softest hands and hardest mouth of any keeper I have ever seen. Ian

Harvey had alien cricket. Matthew Elliott could score runs with his

eyes shut. The first time I saw Dirk Nannes bowl, I felt like Victoria

had thawed a smiley caveman. And even though I never saw Slug Jordan

play, I enjoyed his sledging for years on the radio.

So my favourite player has to be a Victorian. But my other love is

cricket's dark art, legspin. I wish I knew whether it was being a

legspinner that made me love legspin, or seeing a legspinner that made

me want to bowl it. Everything in cricket seemed easy to understand

when I was a kid, but not legspin. And that's where I ended up. I'm

not a good legspinner, far from it, but I think that any legspinner,

even the useless club ones that bowl moon balls, have something special

about them.

The first legspinner I ever fell for was Abdul Qadir. I'm not sure how I

saw him, or what tour it was, but even before I understood actual

legspin, I could see something special about him. His action was

theatrical madness and I loved it.

Then the 1992 World Cup came. I was 12, it was in Melbourne (read

Australia), and this little pudgy-faced kid was embarrassing the world's

best. I was already a legspinner by then, but Mushie made it cool.

This was the age where we were told spinners had no place; it was pace

or nothing. Limited-overs cricket was going to take over from Tests, and

spinners had no role in it. Mushie made that all look ridiculous as he

did his double-arm twirl to propel his killer wrong'uns at groping

moustached legends.

By worshipping Mushie I was ahead of the curve, because from then on, in

Melbourne, Australia, and eventually England, Shane Warne changed the

world. Mushie and Qadir had made legspinning look like it was beyond

the realms of understanding, but Warne made it look like something

humans could do, even if he wasn't human himself.

It was through Warne I got to Anil Kumble. He bowled legspin in such an

understated way. It was completely different to Warne. His wrist

wasn't his weapon, so he had to use everything else he had. Warne was

the Batmobile, Kumble an Audi A4. Anyone could love Warne, his appeal

was obvious. But to love Kumble you needed to really get legspin. The

legspinner's leggie.

When I was young, my second favourite was a guy called Craig Howard, who virtually doesn't exist.

Howard was the Victorian legspinner who Warne thought was better than

him. To my 13- and 14-year-old eyes, Howard was a demon. His legspin

was fast and vicious, but it was his wrong'un that was something

special. Mushie and Qadir had obvious wrong'uns, subtle wrong'uns, and

invisible wrong'uns. Howard had a throat-punching wrong'un. It didn't

just beat you or make you look silly; it attacked you off a length and

flew up at you violently. I've never seen another leggie who can do

that, but neither could Howard. Through bad management and injury he

ended up as an office-working offspinner in Bendigo.

But good things can come from office work. It gave me my favourite

cricketer of all time. A person who for much of his 20s was a

struggling club cricketer no one believed in. But he believed. Even as

he played 2nds cricket, moved clubs, worked in IT for a bank, something

about this man made him continue. A broken marriage and shared custody

of his son. His day job had him moving his way up the chain. The fact

that no one wanted him for higher honours. His age. Cameron White's

legspin flirtation. And eventually the Victorian selectors, who didn't

believe that picking a man over 30 was a good policy.

Through all that, Bryce McGain continued to believe he was good enough. Through most of it, he probably wasn't. He was a club spinner.

Bryce refused to believe that, and using the TV slow-mo and

super-long-lens close-ups for teachers, he stayed sober, learnt from

every spinner he could and forced himself to be better. He refused to

just be mediocre, because Bryce had a dream. It's a dream that every

one one of us has had. The difference is, we don't believe, we don't

hang in, we don't improve, and we end up just moving on.

Bryce refused.

| The world would be a better place if more people saw McGain as a hero and not a failure. He just wanted to fulfil his dream, and that he did against all odds is perhaps one of the great cricket stories of all time | |||

At 32 he was given a brief chance before Victoria put him back in club

cricket. Surely that was his last chance. But Bryce refused to believe

that. And at the age of 35 he began his first full season as

Victoria's spinner. It was an amazing year for Australian spin. It was

the first summer without Warne.

Almost as a joke, and because I loved his story, I started writing on my

newly formed blog that McGain should be playing for Australia. He made

it easy by continually getting wickets, and then even Terry Jenner paid

attention. To us legspinners, Jenner is Angelo Dundee, and his word,

McGain's form and the circumstances meant that Bryce suddenly became the

person most likely.

Stuart MacGill was finished, Brad Hogg wanted out, and Beau Casson was

too gentle. Bryce was ready at the age of 36 to be his country's

first-choice spinner. Then something happened. It was reported in the

least possibly dramatic way ever. McGain had a bad shoulder, the reports said. He may miss a warm-up game.

No, he missed more than that. He missed months. As White, Jason

Krezja, Nathan Hauritz and even Marcus North played before him as

Australia's spinners. This shoulder problem wouldn't go away. And

although Bryce's body hadn't had the workload of the professional

spinners, bowling so much at his advanced age had perhaps been too much

for him. He had only one match to prove he was fit enough for a tour to

South Africa. He took a messy five-for against South Australia and was picked for South Africa. He didn't fly with the rest of the players, though, as he missed his flight. Nothing was ever easy for Bryce.

His second first-class match in six months was a tour match where the South African A team attacked

Bryce mercilessly. Perhaps it was a plan sent down by the main

management, or perhaps they just sensed he wasn't right, but it wasn't

pretty. North played as the spinner in the first two Tests. For the

third Test, North got sick, and it would have seemed like the first bit

of good fortune to come to Bryce since he hurt his shoulder.

At the age of 36, Bryce made his debut

for Australia. It was a dream come true for a man who never stopped

believing. It was one of us playing Test cricket for his country. It

was seen as a joke by many, but even the cynics had to marvel at how

this office worker made it to the baggy green.

I missed the Test live as I was on holidays and proposing to my

now-wife. I'm glad I missed it. Sure, I'd wanted Bryce to fulfill his

dream as much as I'd wanted to fulfill most of mine, but I wouldn't have

liked to see what happened to him live. South Africa clearly saw a

damaged player thrown their way and feasted on him. His figures were

heartbreaking: 0 for 149. Some called it the worst debut in history.

I contacted him after it, and Bryce was amazingly upbeat. He'd make it

back, according to him. He was talking nonsense. There was no way back

for him. Australia wouldn't care that his shoulder wasn't right; he

couldn't handle the pressure. His body, mind and confidence had cracked

under pressure. He was roadkill.

But Bryce wouldn't see it that way, and that's why he's my favourite

cricketer. I wasn't there for all the times no one believed in him, for

all those times his dream was so far away and life was in his way. But I

was there now, at what was obviously the end. Bryce McGain saw the

darkness but refused to enter it. That's special. That is how you

achieve your dreams when everything is against you.

Before I moved to London to embark on my cricket-writing career, I met

Bryce for a lunch interview. It was my first interview with a

cricketer. We were just two former office workers who had escaped. At

this stage Casson had been preferred over him for the tour to the West

Indies. In the Shield final, Bryce's spinning finger had opened up after

a swim in the ocean. He was outbowled by Casson and the selectors

didn't take him. Surely this was it. Why would anyone pick a

36-year-old who had been below his best in his most important game?

Bryce knew he may have blown it. But he still believed, of course. We

were just two former office workers with dreams. Two guys talking about

legspin. Two guys just talking shit and hoping things would work out.

At the time it was just cool to have lunch with this guy I admired, but

now I look back and know I had lunch with the player who would become my

favourite cricketer of all time.

The world would be a better place if more people saw McGain as a hero

and not a failure. Shane Warne was dropped on this planet to be a god.

Bryce McGain just wanted to fulfil his dream, and that he did against

all odds is perhaps one of the great cricket stories of all time.

Bryce is one of us, the one who couldn't give up.

Saturday, 29 September 2012

Not picking the wrong 'un

| |||

Related Links

Players/Officials: Craig Howard | Shane Warne | Michael Beer | Beau Casson | Xavier Doherty | Nathan Hauritz |Brad Hogg | Jason Krejza | Nathan Lyon | Bryce McGain |Stuart MacGill | Marcus North | Steve Smith | Cameron White

Teams: Australia

| |||

Shane Warne's first real victim wasn't a batsman, but a fellow legspinner - a fellow Victorian legspinner, in fact, with a wrong 'un so brutal it would crash into the chest of those who lunged blindly forward; a legspinner who ran in like a graceful 1920s medium-pacer, but who then produced a dramatic twirl of his long arms and ripped the ball off the surface like few teenage legspinners before or since. This legspinner was so good that Warne said he had more talent than he did. His name was Craig Howard. And if you've never heard of him, it's probably not your fault: Howard doesn't even qualify for a single-line biography on ESPNcricinfo.

By December 3, 1995, Warne - who was by then closing in on 200 Test wickets - had already saved legspin. If the date sounds random, then for Howard it was not: it was his final day of first-class cricket. He was 21. Howard retired with 42 wickets in 16 first-class games at 40 apiece, which was no great shakes. But to understand how good he was, you had to be there - you had to see him hit a batsman with his wrong 'un. Aged 19, he had returned second-innings figures of 24.5-9-42-5 at the MCG against the South Africans.Wisden noted: "Only Rhodes, with 59, made much of Howard's leg-spin second time around." Darren Berry, who kept to Howard at Victoria, said he would have named him in his all-time XI of those he had played with or against if it hadn't been for Warne. Yes, Craig Howard could definitely bowl.

Plenty of others have been bit parts in the story of Australia's post-Warne spin apocalypse, but no one has been a more intriguing bit part than Howard. He is the only Australian bowler to go through the Cricket Academy twice, once as the artistic legspinning prodigy from my teenage years, later - after one of his fingers packed in - as a 28-year-old, made-to-order journeyman offspinner. And now Howard is back, plucked from his office job in telecommunications to coach Nathan Lyon, currently Australia's No. 1 tweaker.

Howard, as it happened, did play alongside Warne in four Sheffield Shield games in 1993-94. The comparison is unflattering: Warne took 27 wickets at 23, Howard - who bowled 100 overs to Warne's 247 - three at 108. But in between, with Warne away on international duty, Howard finally got a decent bowl: he took 5 for 112 against Tasmania, including the wicket of Ricky Ponting. More than 15 years later, when another leggie - Bryce McGain, who was almost 37 - was making his Test debut for Australia, the 34-year-old Howard was playing for Strathdale Maristians in Bendigo, up-country Victoria.

He is philosophical now. "Had I played Test cricket, my life would have turned out different," he says. "I probably would have ended up in some sextext scandal and lost my wife and kids and ended up a lonely bum. Although, yes, playing Test cricket was the dream."

There are many reasons why Howard didn't make it: injuries, bad management, terrible advice, over-coaching, low self-confidence. But had he played in an era when Australia were desperate for a spinner, he might now be a household name - or at least someone with a decent blurb on the internet.

"At one stage, there were headlines saying I was going to play for Australia," he says. "I remember being about 20, and at the top of my mark at the MCG. Instead of thinking, 'How I am going to get out Jamie Siddons or Darren Lehmann?' I'm thinking about a small group of men in the ground who are judging me. It wasn't like that all the time, but when I was struggling this is how I felt. In the back of my mind I know the captain of my side doesn't like me, and has told me to f*** off to Tasmania. The coach believes that, because I can't bat or field, I am never going to be that useful. It was a dark time."

In the mid-1990s, no one needed to look for Warne's replacement, because he would play for ever and inspire so many kids to take up legspin that any who fell through the cracks wouldn't be missed. Junior sides each had four or five leggies - often with peroxide hair - and they all walked in slowly, ripped the ball hard, and barely bowled a wrong 'un. But they weren't Warne. None had his physicality: Warne was built like a nightclub bouncer, not a spinner. Massive hands led into awe-inspiring wrists, the whole lot powered by an ox's shoulders. But kids who try the same quickly wear themselves out.

Howard knew how they felt: "My body never backed me up. I couldn't feel my pinky finger, had part of my right arm shortened, tendinitis in my shoulder was operated on, a wrist operation, stress fractures in my shins, tennis elbow in my knees from excessive squat thrusts, a spinning finger with bad ligaments, and barely the fitness to get through a two-day game, let alone four. There was no million-dollar microsurgery in the US for me. In the '90s, you still had to pay for a massage and work a day job.

"There were suddenly legspinning experts everywhere - not ex-spinners but just ex-cricketers, coaches and selectors who spent years ignoring legspin. No one ever came up to you and said: 'You should be more like Warne.' But every bit of advice seemed to be about making you more like him. It wasn't subtle. Everything just created doubt in your mind. And with legspin, if you have an ounce of doubt, you're cactus."

Warne's retirement sparked a desperate search for his replacement. One spinner simply begat the next: Stuart MacGill, Brad Hogg, Beau Casson, Cameron White, Jason Krejza, Nathan Hauritz, Marcus North, Bryce McGain, Hauritz again, Steve Smith, Xavier Doherty, Michael Beer, Nathan Lyon. Never mind Simon Katich, Michael Clarke or Andrew Symonds.

MacGill should have softened the blow of Warne's departure, but his knees gave way, his career as a lifestyle-show TV host took off, and it was clear he just didn't want to bowl any more. Even then, there was Hogg, the chinaman bowler with two World Cup wins to his name. But after one horrendous home summer against India, he retired as well - only to make a bizarre return to international cricket during the Twenty20 home series against the Indians once more, in February 2012, aged all but 41.

Along came Casson, another purveyor of chinamen, but a boyish one who seemed too pure for international cricket. His first (and only) Test was uneventful, and within 12 months he would be out of the Australian set-up altogether after an attack of the yips. A brief comeback was ended by tetralogy of Fallot, a congenital heart defect.

White was captain of Victoria, where he virtually never bowled himself, but suddenly - a product of injuries to others and weird selection - he was Australia's frontline spinner. He was awful. Krejza eventually got a chance and, on Test debut in Nagpur, claimed 12 wickets. The problem was he also gave away 358 runs; he played only one more Test. Marcus North became a Test batsman because he could bowl handy offspin, some said better than Hauritz. But despite a flattering six-wicket haul against Pakistan at Lord's, North's offbreaks were gentle; and they weren't much help when his batting faded.

McGain made his debut amid plenty of jokes about Bob Holland, who was 38 when he first played for Australia. McGain was an IT professional in a bank, who had never really been especially close to state selection. But he wouldn't go away. And while the search focused on big-turning kids, McGain sneaked into the Victoria side. In the 12 months before his Test debut, a shoulder injury had limited him to four first-class games. When the day finally came, at Newlands, McGain was roadkill: 18-2-149-0. That was it. McGain now plays part-time in the Big Bash League.

Hauritz was not deemed good enough even for New South Wales. He was a timid offspinner from club cricket with a first-class bowling average of more than 50, but he fought hard and improved regularly. The trouble was Hauritz was neither an attacker nor a defender, and Chris Gayle said it was like facing himself. By the time Hauritz was dumped, he was in the best form of his career.

A young allrounder named Steve Smith bowled legspin, and was brought in to play Pakistan in England. He madea dashing 77, was dropped and then later recalled in the Ashes as a batsman who bowled a bit - just not very well.

Xavier Doherty was given a go because Kevin Pietersen kept falling to left-arm spin. He got his man - but for 227. So in came Michael Beer, who admitted he probably wasn't ready for Test cricket, and then proved it.

| Bowler | Style | Test debut | Matches | Runs | Wkts | BB | Avg | SR | Econ |

| Shane Warne | LBG | 1991-92 | 145 | 17,995 | 708 | 8-71 | 25.41 | 57.49 | 2.65 |

| Brag Hogg | SLC | 1996-97 | 7 | 933 | 17 | 2-40 | 54.88 | 89.64 | 3.67 |

| Stuart MacGill | LBG | 1997-98 | 44 | 6038 | 208 | 8-108 | 29.02 | 54.02 | 3.22 |

| Nathan Hauritz | OB | 2004-05 | 17 | 2204 | 63 | 5-53 | 34.98 | 66.66 | 3.14 |

| Beau Casson | SLC | 2007-08 | 1 | 129 | 3 | 3-86 | 43.00 | 64.00 | 4.03 |

| Cameron White | LBG | 2008-09 | 4 | 342 | 5 | 2-71 | 68.40 | 111.60 | 3.67 |

| Jason Krejza | OB | 2008-09 | 2 | 562 | 13 | 8-215 | 43.23 | 57.15 | 4.53 |

| Marcus North | OB | 2008-09 | 21 | 591 | 14 | 6-55 | 42.21 | 89.85 | 2.81 |

| Bryce McGain | LBG | 2008-09 | 1 | 149 | 0 | 0-149 | - | - | 8.27 |

| Steve Smith | LBG | 2010 | 5 | 220 | 3 | 3-51 | 73.33 | 124.00 | 3.54 |

| Xavier Doherty | SLA | 2010-11 | 2 | 306 | 3 | 2-41 | 102.00 | 151.66 | 4.03 |

| Michael Beer | SLA | 2010-11 | 1 | 112 | 1 | 1-112 | 112.00 | 228.00 | 2.94 |

| Nathan Lyon | OB | 2011-12 | 10 | 832 | 29 | 5-34 | 28.68 | 55.72 | 3.08 |

The first anyone in Australian cricket heard of Nathan Lyon was when Kerry O'Keeffe mentioned him on radio. At that stage, Lyon was part of the Adelaide Oval groundstaff, and was travelling to Canberra to play for the second XI. After some good performances in the nets, Darren Berry - now Adelaide's Twenty20 coach - took a punt on him. Lyon suddenly looked like the best spin prospect in the country - which wasn't saying much.

Howard really had come along at the wrong time. But there were moments, before I finally spoke to him, when I wondered if he actually existed at all. Finding someone who remembered his name was hard enough; finding someone who'd seen him play next to impossible. I'd talk to a guy, who'd tell me to contact a guy, but that guy would also tell me to contact a guy. The leads never went anywhere. Craig Howard wasn't the missing link of Australian spin bowling: he was just missing.

Then I asked Gideon Haigh about Howard, and he gave a long stare, as if he was searching through his billion-terabyte memory. I had my breakthrough. Haigh talked about how Howard looked like an otherworldly artist - long shirt buttoned to the wrist, billowing madly in the wind; incredibly gawky, like a schoolkid. Howard didn't fit into Haigh's, or anyone else's, imaginings of an athlete. But it was the Howard of my youth. Someone else remembered my poet leggie.

After that I cornered O'Keeffe, legspin's court jester. He had coached Howard at the Academy, probably twice. O'Keeffe's eyes were full of regret: he said Howard had a biomechanically flawed action, and O'Keeffe hadn't tried to fix it. But that didn't stop him happily reminiscing about "a wrong 'un batsmen had to play from their earhole".

I collared Damien Fleming, Howard's Victoria colleague. Fleming seemed surprised to hear the name again. He told stories about how he thought Victoria had a champion on their hands, but said his skin folds were thicker than those of Warne or Merv Hughes: "Basically bone and fat." He could have gone further with a more supportive coaching structure, said Fleming. He added, almost lustfully: "The best wrong 'un I've seen." Then came the clincher. "If someone like him came on the scene now, he'd be given everything he needed to succeed. Like they treat Pat Cummins."

Haigh, O'Keeffe and Fleming all seemed to think Howard was a Test spinner we had missed out on. They could be right. But Howard was caught between two eras, relaxed and regimented. And Australia had Warne.

"My career is long over," says Howard. "It finished with me out of form and mostly injured. It wasn't one thing that ended my career, and I'm not coming up with excuses, but this is what happened to me. Due to my finger, I can't even bowl legspin any more - I have to bowl offspin, but nothing can ever compare to being a legspinner. I'm younger than Hogg, McGain or MacGill and instead of preparing to play in my 100th Test and thinking about retirement, I am working in an office in Bendigo."

Craig Howard went from a freakishly talented wrist-spinner to a boring club offie. Australian spin did much the same.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)