Social historian Ramachandra Guha can easily cast a spell on the listener with his deep knowledge and his spontaneity. Guha, who was briefly, in 2017, a member of the Committee of Administrators appointed by the Supreme Court of India to oversee reforms in the BCCI, has written a cricket memoir, The Commonwealth of Cricket that traces his relationship with the sport from the time he was four. He says it will be his last cricket book, but as he reveals in the following interview, he will continue his love affair with the game - despite the way it is administered in India. Courtesy Cricinfo

This is your first cricket book in nearly two decades, after A Corner of the Foreign Field was published in 2002. Why did you decide to write it now?

Two things. One, I wanted to pay tribute to my uncle Dorai, my first cricketing mentor and an exemplary coach and lover of the game, who is still active at the age of 84, running his club. I knew at some stage I would like to pay tribute to him.

Paying tribute to people I admire, respect, have been influenced by, is something I have done through my writing career. I have written about environmentalists, scholars, biographers, civil liberties activists. So I also wanted to write about this cricketer [Dorai] who had inspired me.

And I did my stint at the board. That kind of completed the journey from cricket-mad boy through player and writer and spectator to actually being inside the belly of the beast. So I thought that the arc is complete and maybe I should write a book.

In the book you have defined four types of superstars: 1. Crooks who consort with and pimp for bigger non-cricket-playing crooks. 2. Those who are willing and keen to practise conflict of interest explicitly. 3. Those who will try to be on the right side of the law but stay absolutely silent on […] those in categories 1 and 2. 4. Those who are themselves clean and also question those in categories 1 and 2." Bishan Bedi, you say, is the only one you can think of in that last category. Why is that?

Because he is a person of enormous character, integrity and principle. He never equivocates, he never makes excuses. And he calls it as it is. These kinds of people are rare in public life in India. They are rare in the film world, they are rare in the business world, and virtually invisible in politics. They are rare also in journalism, if you go by the ways in which editors in Delhi, for many years, have been intrigued with politicians, sought Rajya Sabha seats or favours, houses for themselves…

To find someone like Bishan Bedi, who is ramrod straight in his conduct, in any sphere of public life in India today is increasingly rare. He is also an incredibly generous man. When I first met him, at my uncle's house for dinner, he gave a cricket bat to my uncle - because he never wants to take freebies.

Bishan always has given back much more to youngsters he has nurtured. He is very blunt, he is abrasive, like me. He makes enemies because he sometimes says things in an indiscreet or impolite way. But it's really the quality and calibre of his character that compels admiration in me today. When I was young, it was the art and beauty of his spin bowling. Today, it's the kind of man he is.

You write that the superstar culture "that afflicts the BCCI means that the more famous the player (former or present) the more leeway he is allowed in violating norms and procedures". How does that start?

Your question compels me to reflect on a time when players had too little power. When Bedi once gave a television interview where he said some sarcastic things, he was banned for a [Test] match in Bangalore in 1974. Players had to get more power, they had to get organised, they had to be noticed, they had to be paid properly, which took a very long time. The generation of Bedi and [Sunil] Gavaskar was not really paid well till the fag end of their careers.

But now to elevate them into demigods and icons… one of the things I talk about is [Virat] Kohli and [Anil] Kumble and their rift [Kumble was forced to step down as coach after the 2017 Champions Trophy]. How essentially Kohli had a veto over who could be his coach, which is not the case in any sporting team anywhere.

[MS] Dhoni had decided: I'm not going to play Test cricket. He was only playing one-day cricket. And I said [in the CoA] that he should not get a [Grade] A contract. Simple. That contract is for people who play throughout the year. He has said, "I'm not playing Test cricket." Fine. That's his choice and he can be picked for the shorter form if he is good enough. [They said] "No, we are too scared to demote him from A to B." And more than the board, the CoA, appointed by the Supreme Court, chaired by a senior IAS officer, was too scared. I thought it was hugely, hugely problematic. So I protested about it while I was there. And when I got nowhere, I wrote about it.

Is it the fans who create this culture?

Of course. They venerate cricketers. That's fine. Cricketers do things that they cannot do. It's the administrators who have to have a sense of balance and proportion. And not just with cricketing superstars who are active but also superstars who are retired. Again, to go back to one of the examples I talk about in my book: that [Rahul] Dravid could have an IPL contract, but other coaches in the NCA couldn't. Now, you can't have double standards like this. Cricket is supposed to be played with a straight bat.

It is not Dravid's fault. He just used the rules as they existed for him. It was the fault of the BCCI management that it created this kind of division and caste system within cricketers, within coaches, within umpires, within commentators. It offended my ethical sensibilities. So I protested.

You recently told Mid-Day that "N Srinivasan and Amit Shah are effectively running Indian cricket today".

It is true.

Are they really running the board?

Yeah, that's my sense. Along with their sons and daughters and sycophants. That's what it is. And [Sourav] Ganguly [the BCCI president] has capitulated. I mean, there are things he should not be doing, given his extraordinary playing record and his credibility, whether he should be practising this shocking conflict of interest. The kind of example it sets is abysmal. I say this with some sadness because I admired Ganguly as a cricketer and as a captain. I'm glad I'm out of it and I'm just a fan again. I can just enjoy the game and not bother about the murkiness within the administration.

Things were meant to change under Ganguly.

Again, I go back to what I said about Bedi: people of principle are rare in any walk of life. And in India, particularly, there is a temptation for fame, for glory, to cosy up to who's powerful. It's very, very, very sad, but it happens. Maybe it's something to do with a deep flaw in our national character, that we lack a backbone in these matters.

In the book, where you address the topic across two chapters, as well as during your tenure in the CoA, you say you were frustrated by how deep the roots of conflict of interest have grown, not just in the BCCI and state associations but also across the player fraternity. Why is it so difficult for both administrators and players, some of whom are former greats, to understand conflict?

Because it's ubiquitous and everybody is practising it. Woh bhi kar raha hai, main bhi karoonga. Kya hai usme? [He's doing it, so I'll also do it. What's the big deal?] It's hard to resist, you know, especially [when] the moral compass of people around you is so low that you just kind of go along with it.

Sunil Gavaskar is another person who said had multiple conflict of interests.

To Dravid's credit, he saw the point and gave up his Delhi Daredevils contract relatively quickly. He exploited the rules as they were and once I protested and it became public, he realised that he had probably erred and done a wrong thing. Maybe Ganguly could have learned from Dravid in what he's doing now. Cleaning up Indian cricket is a lost cause.

In 2018, the Supreme Court modified its original order of 2016, passed by Chief Justice TS Thakur concerning the Lodha reforms. In 2019, immediately after taking over, Ganguly's administration asked the court to relax key reforms, which would virtually wipe out the reforms. Is it now the responsibility of the court to decisively put the lid on the case?

I'm not losing any sleep. Cricket lovers have to live with a corrupt and nepotistic mode. We should just move on and enjoy the cricket.

In the book, you say you write on history for a living and on cricket to live. Can you tell us a bit more about that?

When I started writing this book, I had just finished the second volume of my Gandhi biography. It's a thousand pages long, inundated with millions of footnotes. And when you write a properly researched work of history, you have to have your sources at hand. So you compile a paragraph, which is based on material you gather, and then you have to scrupulously footnote that paragraph. One paragraph may be drawn from four different sources - a newspaper, an archival document, a book - and you have to put all that in.

Whereas I wanted to write this freely and spontaneously. I could only do that in the form of cricket memoir. So that's how it happened. I wanted a release from densely footnoted, closely argued, scrupulously researched scholarly work. And this came as a kind of liberation.

You call yourself a cricket fanatic. For me, on reading the book, it's the romantic in you that comes to life.

Yeah, I think I am more a romantic than a fanatic. I'm cricket-obsessed. I've been cricket-obsessed all my life, but more in a romantic way; "fanatic" may be slightly wrong because that assumes you always want your team to win. And that's certainly not the case with me anymore.

You write in the book about a fanboy moment you had: "On this evening I did something I almost never do - take a selfie, with Bishan Bedi and the coach of the Indian team, Anil Kumble." Can you recount that incident?

It was the BCCI's annual function. One of the few things I was able to do in my brief tenure at the board was accomplished on that day: to have [Padmakar] Shivalkar and [Rajinder] Goel, two great left-arm spinners, get the CK Nayudu [Lifetime Achievement] Award - the first time a non-Test cricketer had been honoured. And also to have Shanta Rangaswamy get the first Lifetime Achievement Award for Women.

So it was a happy occasion. It was in my home town [Bengaluru]. Bishan had come from Delhi. Kumble was then the coach of the [Indian] team. I know Bishan well and Anil a little bit. I don't know that many cricketers, actually. All these years running about the game, my only friend is really Bishan Bedi, apart from Arun Lal, who was my college captain.

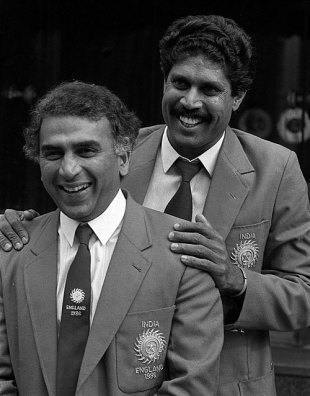

Kumble, of course, would admire Bishan as a kind of sardar [chief] of Indian spin bowling. I saw them and I said I'll take a selfie. What I don't mention is that the selfie was taken by Anil, because he is technologically much more sophisticated than either Bishan or me. He took that selfie very artfully, which I would not have been able to do. It came out nicely. It is the only photograph in the book.

I am a partisan of bowlers and of spin bowlers. For me, Kumble has always been underappreciated as a cricketer. To win a Test match you need to take 20 wickets. And, arguably, Kumble has therefore won more Test matches than Sachin Tendulkar. As I again say in the book, in 1999, when Tendulkar was about to be replaced as captain, they should really have had Kumble - he is a masterful cricketing mind, but there is a prejudice against bowlers. So in a sense, [the photo was with] someone who was a generation older than me, Bedi, and someone of a generation younger than me, Kumble - both cricketers I admire, both with big hearts, and both spin bowlers, as I was myself.

That's why the caption says: "two great spin bowlers and another" - kind of implying I was a spin bowler, but a rather ordinary one.

Is it true that this possibly could be your last cricket book?

Almost certainly. It would be, because I really have nothing else to say. This is a kind of cricketing autobiography and it has covered a lot. This is my fourth cricket book. I will watch the game. I will appreciate it.

Why don't more Indian cricketers write books?

I think Dravid has a great book in him because he is a thinking cricketer. So might Kumble. But my suspicion is, Kumble will not write a book. Dravid just might. He could write a book called The Art of Batsmanship. Bedi could have written a book because he is an intelligent person. He writes interesting articles, including on politics and public life. By the way, books don't sell. That's another reason. Occasionally, cricketers have thought, I will write a book and I will make Rs 30-40 lakhs (about US$50,000) on it. But cricket books don't really make that much money.