Narendra Hirwani: "My message to spinners like R Ashwin is, bowl your stock delivery 80% of the time in first-class cricket" © AFP

Two years ago, when England won the Test series in India 2-1, R Ashwin, India's favoured offspinner since the dropping of Harbhajan Singh, took 14 wickets at 52.64. This summer in England, Ashwin played the final two Tests of the five-match series; Ravindra Jadeja played in the first four. Their combined aggregate of 12 wickets was seven fewer than the tally of the best spinner in the series: England's Moeen Ali, a part-timer.

On India's domestic circuit, spinners have ceded place to seamers. In the last three seasons of the Ranji Trophy, only Shahbaz Nadeem, the Jharkhand left-arm spinner, has finished among the top-five wicket-takers. Till the turn of the millennium, Ranji teams had high-quality spinners who were at par with those playing for the national side. Now, a country that boasted the likes of Erapalli Prasanna, Bishan Bedi, BS Chandrasekhar, Maninder Singh, Narendra Hirwani, Venkatapathy Raju, Anil Kumble, Sunil Joshi and Harbhajan Singh suddenly finds its pool dry.

What are the factors that have contributed to this decline? Five experts - Bishan Bedi, Maninder Singh, Narendra Hirwani, Murali Kartik and Amol Muzumdar - share their thoughts.

A lack of quality spin

Bishan Bedi (former India left-arm spinner and captain): Where is India's next-generation spinner coming from? We are at a very strange crossroads where everybody and anybody wants to get into the team in a fast manner. That does not happen when it comes to spin bowling. Spin bowling is all about learning your craft over a period of time. You can't learn spin bowling by just delivering four overs in a T20 match.

Murali Kartik: (former Railways and India left-arm spinner): We have come to a stage where even a part-time bowler is being looked at as a spinner. To bowl spin there are lots of important basics in technique that need to be developed. That is not happening right now because the youngsters at the grass-roots level are playing the limited-overs versions. Before you are learning what your action is, learning how to bowl the conventional form of spin, the thing that is happening now is, because of the lure of money, youngsters want to play the shortest format.

At the age of 18 or 19, if you ask a spinner to play T20 and then ask him to bowl well in four-day cricket, it will not be possible. Even within India, you are not getting spinners to bowl well, even if you give them spinning pitches. So they do not have the wherewithal to bowl at all overseas.

Amol Muzumdar: (former Mumbai batsman and captain) The spinners are not a threat anymore. When does a batsman feel threatened at the crease? Only when the ball has fizz. If you are darting the ball at him, I am happy [as a batsman], absolutely happy to face that. But when the ball fizzes off the surface, when it has flight and spin, then batting is not easy. And that is not seen anymore.

I remember facing Venkatapathy Raju in Mumbai in my early years of first-class cricket. I could hear the turn in the air. Same with Maninder Singh. That really put me in my crease. I told myself I had to be careful. They put me on the back foot.

Narendra Hirwani: (former India legspinner and former national selector) There was a time when the level of spinners at Ranji Trophy and Test level was virtually the same. That divide has become very big now. During Bishan paaji's time there were Padmakar Shivalkar and Rajinder Goel, who were equally good left-arm spinners.

Today the youngsters are a little too smart for their own good. When you become too smart, you become cautious. But these youngsters do not understand that every batsman is afraid of spin.

Maninder Singh: (fomer India left-arm spinner) This is a concern. The BCCI did not either realise or it did not bother to make sure young spinners coming up did not start drifting towards T20 cricket. I will give the example of Akshar Patel, the Kings XI Punjab [and Gujarat] left-arm spinner. He darts everything in to the batsman, which is absolutely fine for T20, but I hope it does not become a habit.

| | | |

|

| "I would feel good only when I had bowled sufficient hours to get confidence in the nets, which then I could take in to the match. I would bowl at least seven to eight hours every day. I was obsessed"Bishan Bedi |

|

| | |

|

The part pitches play

Kartik: It was a knee-jerk reaction [making green pitches] when we lost Test series in England and Australia in 2011 and 2012. The thought process was we needed to play on wickets which are conducive to fast bowling.

In India, say I win the toss on a green pitch and ask the opposition to bat. I play three seamers, a batting allrounder who can bowl a little, and a spinner. Generally, if you bundle out the opposition anywhere between 120-220 runs, the next thing you do is you ask for a heavy roller when it is your turn to bat. So over four innings, by the time the match is into the third day and when the wicket is supposed to disintegrate, because the heavy roller has been used, the wicket is no longer green for the seamers. It becomes a flat deck. And because of the grass cover that has been rolled time and again, there are no natural variations, there are no footmarks. So even on the fourth day there is nothing for a spinner.

Also, the SG Test ball, which is used in domestic first-class cricket, starts [reverse] swinging once the ball is 30 to 40 overs old. By the time the spinner comes in to bowl the ball is about 60 overs old. But he gets only about ten overs to do the holding job on a pitch made for the seamers.

I bowled a total of 71 overs during the 2013-14 season in seven matches for Railways. Out of that, for ten overs I ran in and bowled seam-up against Tamil Nadu at the Jamia Millia ground in Delhi. At times we have played on pitches that resembled the Wimbledon tennis courts.

I can still bowl on those wickets because I have bowled in the conventional four-day method. Harbhajan Singh has done that. [Ramesh] Powar has done that. Sunil Joshi has done that. But Ravindra Jadeja, Iqbal Abdulla, Vishal Dabholkar have learned only the restrictive way of bowling: round-arm, undercutting. That is what is happening closer to the grass-roots.

Making spin-friendly pitches is no foolproof solution. By doing that the spinner goes in with a false sense of confidence that he has taken lots of wickets. But you are still not a complete bowler. Your skill sets are not up to the mark.

Hirwani: I have always said that a spinner should train on a wicket where he needs to make the ball turn. Not on pitches that take turn easily. It should be a pitch where you need the skills - not everyone can spin on it.

A defensive attitude

Bedi: There is no imagination. You are only playing a waiting game. So the batsman will always be on top. You have to make a batsman do what you want him to do. Spin bowling is a philosophy. How to outwit your opponent. It can be compared with playing chess. It is not bowling flat, like young Indian bowlers, even Jadeja, are doing.

|

| Maninder Singh: "Akshar Patel darts everything in to the batsman, which is fine for T20. But I hope it does not become a habit" © BCCI |

Enlarge

|

|

|

Hirwani: I feel the main reason behind that is if the idea is to minimise the runs I want to concede, I need to not reduce the spin on the ball. If you spin less, then you could give less runs, but you also reduce the chances of taking a wicket. So if you minimise taking risks, you also cut down your chances of taking a wicket. The shorter versions of the game have started affecting some spinners.

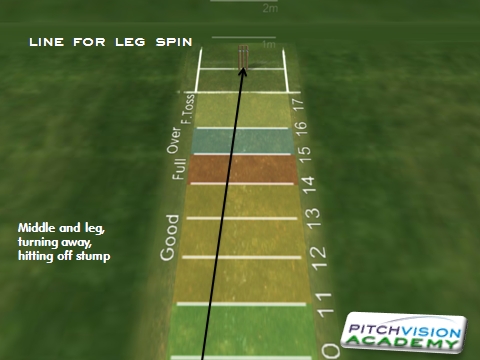

Take even Harbhajan Singh. Why did he slide in the latter half of his career? He started to focus more on checking the runs. His line started to go towards the middle stump and that reduced his chances of taking wickets. An attacking line for an offspinner is pitching on the fifth stump [outside off], where he is trying to get the batsman bowled by breaking in. The moment he brings the line inside, he starts becoming defensive. That means only if the batsman makes a mistake will you get a wicket. But then how are you forcing the batsman to commit a mistake?

My message to even senior spinners like R Ashwin is: bowl your stock delivery 80% of the time in first-class cricket, and for rest of the time you can use the variations as a surprise. A spinner should not become predictable.

Kartik: Even in first-class cricket, spinners and captains now place a long-on, long-off, deep point with silly point and short leg, when all you are doing is darting the ball. To dart you do not need to know the fundamentals of spin bowling. To bowl flight, to beat the batsman in the air, to spin the ball, you need the basics to be very strong. It takes time.

Is modern coaching to blame?

Muzumdar: Earlier there were spinners with different actions. In the 1980s there was Maninder Singh, Ravi Shastri, Venkatapathy Raju and so many others. But all had different actions which were natural. That is the essence of spin bowling - keep your action natural. I think now we are over-coaching some youngsters.

Take Harmeet Singh, the Mumbai left-arm spinner. When I saw him a few years ago in the indoor nets in Mumbai, he had a unique action. It was not the conventional action. His front foot would land with a heavy thrust on the ground. That was his skill and it helped him deliver the ball nicely. But now he delivers with a much lower arm and that is because he has changed his action. I fear we have lost one more good spinner due to over-coaching.

Maninder: As a coach, I do not try and change the action at all. I try to look at the strengths of the youngster and coach accordingly. But I have seen certified coaches teach kids about the arm coming from a certain height and degree. I would rather focus on the youngster's natural arc and polish that.

Hirwani: Many of my students at my academy in Indore tell me: "Sir, I have bowled 60 balls. Sir, I have bowled 50 balls today." I tell them: if you want to make cream, you have to condense it, and that only happens after boiling it for a period of time. A good rabri [sweet] is made only when the cream rises. For quality you need quantity.

I would bowl minimum of 90 overs a day as a youngster at the Cricket Club of Indore. I would bowl at just one stump for a couple of hours. In all, I would bowl for a minimum of five hours. If you are bowling at one stump you end up bowling about 30 overs in an hour. This kind of training, bowling at one stump, is equivalent to vocalists doing riyaaz [music practice]. You build your muscle memory.

Bedi: I keep hearing about pitching it in the right areas. The right areas is between your ears, in your mind.

I also had an outstanding coach. He gave me a lot of cricket sense. Cricket ability and cricket sense are two different things.

You just have to bowl. Bowl and bowl and bowl. I would feel good only when I had bowled sufficient hours to get the confidence first in the nets which then I could take in to the match. It took me a long, long time to learn good bowling. I would bowl at least seven to eight hours every day. I was obsessed.

The importance of captains

Muzumdar: As a captain you have to be patient. You need to relax even if a four or six is hit off a spinner. Nowadays batsmen go after a slow bowler, especially ones who do not impart too much spin on the ball, as soon as he comes in to bowl. So the captain immediately says to keep it tight till his fast bowlers can come back.

I saw the rise of Sairaj Bahutule under Sanjay Manjrekar, Ravi Shastri and Sachin Tendulkar. After about four years, I think, Sairaj picked his first five-for. You had to be patient. And I saw the development in Sairaj in that period. Against Delhi in a Ranji Trophy match, Ajay Sharma was taking control but Manjrekar persisted with Sairaj and Nilesh Kulkarni though Sharma was playing aggressively against the spinners. In the end Mumbai won that match.

Kartik: A captain can make or break a spinner. So he should understand what the spinner goes through, how they function and how they can be turned to match-winners. When the captain wants you to give as few runs as possible, he is not giving the spinner any confidence.

Maninder: Take the example of Gautam Gambhir. I have seen him in T20 cricket place a silly point and a short leg as soon as a wicket falls, when a spinner is bowling. Dhoni does not do that when a new batsman comes in in a Test match. When I had those close-in fielders my focus and concentration went a notch higher. But for that you have to have the habit of bowling with those fielders. With time your confidence goes high and also you stop worrying if you bowl a long hop or a full toss.

| | | |

|

| "If a spinner starts at the age of 12 or 13, he needs seven to eight years to understand his bowling"Murali Kartik |

|

| | |

|

New talent on the horizon

Kartik: There are a few slow bowlers but not a spinner. When I started playing first-class cricket there were good spinners who were not getting a place in their state squads. Sunil Joshi, Kanwaljeet Singh, Sunil Subramaniam, Narendra Hirwani, Rajesh Chauhan, Bharati Vij, Sunil Lahore, Pradeep Jain, Rahul Sanghvi, Sarandeep Singh, Harbhajan Singh were quality spinners. Now I can't take a single name.

Hirwani: I have faith in two: Bengal offspinner Aamir Gani, who just turned 18. He has the skills and the desire. I also like Kuldeep Yadav, the chinaman bowler from Uttar Pradesh. He is an attacking bowler.

Maninder: Kuldeep Yadav, if the slight technical flaw in his front arm is fixed.

The problem with T20

Kartik: T20 cricket is not only harmful for a young spinner, it can also affect a senior bowler. Take Pragyan Ojha. He went at the rate of five an over, did not get a wicket in his 35 overs in the one Test he played on the India A tour of Australia in July. This is a spinner who has taken more than 100 Test wickets. He is confused after he has come back. So you can imagine the state of a young bowler who does not know his game inside out. All he is doing is bowling four overs for 25-30 runs and getting one wicket off a good or bad ball, because you know the next day you are up and running for the next T20 match.

Bedi: The modern generation is all about the IPL. Tell me if you get Rs 9, 10, 12 crore why would you want to bowl 35 overs [in a first-class match] for five lakhs? Sport is about money in the modern context.

The way out

Maninder: It is the BCCI's responsibility. When the IPL started, it had a lot of enemies. But that was also the time the BCCI should have taken the challenge of creating a pool of young talent and putting them under the expert guidance of former players or greats. These guys would not just talk about the specifics of spin bowling but also talk to them about how to sustain in the longer format of the game. If you speak to Bishan Bedi, the way he communicates, you would think: five-day cricket is what I want to play.

Kartik: If you are trying to push 11-year-olds into T20 cricket you are never going to learn the art of spin. Till the age of 21 at the state and age-group level at least, there should be no exposure to T20 cricket. Kids should play only three- or four-day cricket - learn to flight to ball, learn to get hit. By getting hit your natural survival instinct kicks in. Right now the natural instinct in T20 is to bowl quick. When you do that you cannot go back and bowl in four-day cricket, where you are trying to prise out a wicket.

If a spinner starts at the age of 12 or 13 he needs at least seven to eight years to understand his bowling: to bowl up and over, to flight the ball, to give the revs, and such things. You can coach, but if you are not allowing the player to first learn and understand his own game there is no point. Technically Test cricket is the deep end because getting a wicket when the batsman is defending is difficult

.