India's youngest and most distinguished captain on the importance of honesty, transparency and inspiration when leading a side

To measure Tiger Pataudi by his captaincy record is to do him no justice. His true contribution lies in his seminal influence on Indian cricket: the manner in which he lifted it from its abyss of diffidence and negativity and instilled a belief to contemplate victory. He took over the reins as a 21-year-old in the fourth Test against West Indies in 1961-62, and went on to lead in all but six of his 46 Tests. He brought to the captaincy a tactical boldness and an originality of thinking rarely seen in India. Long before Clive Lloyd unleashed four fast bowlers on the world, Pataudi employed four spinners, doing away with the tokenism that characterised Indian new-ball bowling back then.

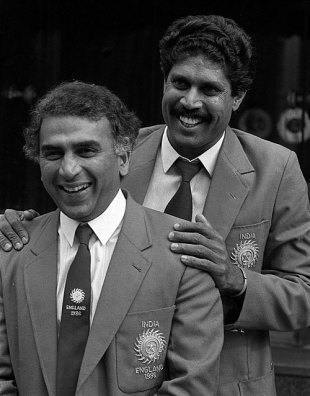

"A captain has to be honest, to the team and to himself. It should be obvious that the best interests of the team should be top of his agenda"© PA Photos

You once famously said that captaincy is all about either pulling from the front or pushing from behind. We could begin with an elaboration.

You once famously said that captaincy is all about either pulling from the front or pushing from behind. We could begin with an elaboration.

What I meant was that you had some captains who were great players themselves - [Don] Bradman, [Garry] Sobers, [Richie] Benaud. They led by the sheer force of their performance. Then there were captains like [Mike] Brearley, [Ray] Illingworth, myself to an extent, who were not the best players in their sides. We had to push the team from behind, get the best players to perform to the best of their ability. Bradman and Sobers walked ahead and others followed. Inspiration flowed from their performances. Whereas a captain who is not a terribly inspiring performer himself has to rely on extracting the maximum from his best players.

Would you say a non-performing captain has a much tougher task because of his over-reliance on others?

Brearley may have averaged less than 25 with the bat, but his great success lay in the way he brought out the best in Ian Botham. Brearley didn't lead in the field, he didn't go out and score 190 and say, "Now you follow my example." He coaxed and cajoled the others to perform. Bradman didn't need to do that. He went out and won matches with his own bat. Sobers wasn't the greatest of captains, but he just did everything himself. In my case, I had to get the best out of [Gundappa] Viswanath. He was our best batsman for a long time. I had to push him to give his best.

And how did you do that?

The first and most critical thing is to make a player realise his true worth - sometimes players themselves don't know how good they can be. Then you make him realise his importance to the team, how the team depends on him, and how he will let his side down if he doesn't perform at his very best. It's not very complicated really, but small things do make a big difference. As I said, you either get the team behind you or in front of you.

There is a management principle that a leader needs to be different things to different people. Doesn't captaincy require similar role-playing? Friend to some, guide to some, father figure to some and taskmaster to some?

There is a management principle that a leader needs to be different things to different people. Doesn't captaincy require similar role-playing? Friend to some, guide to some, father figure to some and taskmaster to some?

First and foremost, a captain has to be honest, to the team and to himself. It should be obvious that the best interests of the team should be top of his agenda. His team-mates must feel in their hearts that the captain's personal interests come below that of the team. We have had one or two captains who were always more concerned with their own performance.

Would you care to name them?

No, I wouldn't want to go into that, but people will know who I am talking about. When you have a captain who is more bothered about his own performance, it's difficult for him to get the loyalty and respect of his team-mates. Particularly in the Indian context, where there are so many internal dynamics operating, the captain has to be absolutely transparent. At no stage should any player feel discriminated against or feel that there is a bias against him. If a captain is honest and transparent, he can take harsh decisions without creating any ill will. The other thing is to always pick your best team. Pick the best batsmen, pick the best bowlers. It doesn't matter who you are playing or where.

So you are saying team selection should not be based on conditions or opposition?

Absolutely. I have never believed in the horses-for-courses theory. Harbhajan [Singh] will get you wickets on a green top and Kapil Dev will get you wickets on a turner, because they are both good bowlers. A bad seamer will not get you wickets on a green top and a bad spinner will not get you wickets on a turner. I played four spinners because they happened to be the best bowlers around. I had no Kapil Dev, so playing a seamer just for the sake of balance was useless.

And you wouldn't be concerned if a couple of them were difficult characters?

That's what a good captain is all about. If he thinks that the player has ability, it's his job to manage his personality. Every team has a couple of difficult characters - in my time there were a few. Salim Durani was one. I felt I couldn't handle him very well.

Why would you say that?

Because I felt I couldn't get the best out of him. He was an extremely talented cricketer who lacked a certain amount of cricketing discipline. We tried to organise it - me and a few other senior players. But we didn't succeed. He did well, but a man of his talent could have been made to perform much better.

Do intuition and instinct play a role in captaincy? Or is it mostly about method and strategy?

To start with, the fundamentals have to be solid. Intuition comes with experience. Over the years you acquire a certain knowledge and hindsight which help you to play to a particular percentage. You instinctively know that certain things will happen in certain situations and you make your moves. But your basic analysis and basic strategy have to be correct. Most of all, you need to be a good student of the game. Many things could go wrong even if you do the right things because a lot depends on how others perform. But if your basics are wrong, you've got no chance.

"A captain can't make a player perform beyond his ability. That's impossible. But very often, players are performing at only 50% of their ability. A good captain lifts that up to 80% and 90%. And I think Brearley got Botham to perform at 100%"

And the captain must seize the moment…

Yes, the sooner you are able to see the moment, the sooner you act. Sometimes moments come and go. Good captains, experienced captains, know to utilise the smallest openings. Sometimes two overs can change a game.

Is this ability to recognise a moment, see an opening, a gift of nature or can it be developed?

You have to be alert and you have to be thinking all the time. And to be a thinker, you must be familiar with cricket history. Reading a bit of cricket literature, knowing about great players of the past helps. Unfortunately, not many modern players read anything.

Do you think that stunts their growth?

I will say reading helps. It broadens your vision. It gives you perspective. Perspective does not come from watching television.

To be fair to them, modern players have very little time.

Oh, they have plenty of time to do ads. If you want to, you can find the time.

Would you say education plays a critical role in making a successful captain? Is it a coincidence that some of the great captains have been well educated? Imran Khan, Richie Benaud, Brearley, yourself...

Education is important, I wouldn't say it is mandatory. Education gives you some kind of depth, an outlook on your own life and life outside. It makes you less parochial. But there have been exceptions. Lala Amarnath was a good captain and he wasn't highly educated.

But isn't there something called a natural cricket sense, an inborn feel for the game? Most of us thought Tendulkar would be a natural captain.

Great players don't necessarily make great captains. The trouble with natural cricketers is that they never have to think about the game. Everything comes so easily to them. You ask them to coach somebody and they wouldn't know what to do. They have never had to learn, never had to study. Everything is so instinctive for them.

You became captain at 21. How well acquainted were you with the history and traditions of the game?

I had very little idea. I was lucky that the senior players were very supportive. Polly [Umrigar], Jai [ML Jaisimha], they were all very experienced. I borrowed a lot from them. And then I learned. I had captained Sussex previously, but that was a different ball game. Then I captained Delhi. But captaining an Anglo-Saxon side is different from captaining India. The politics here are so convoluted. It takes a little while to get used to.

Captaining India is surely not one of easiest jobs in cricket...

Oh, it's a unique problem in itself. But I was lucky that one or two senior players were retiring at the end of the West Indies tour [1961-62]. And a lot of us were youngsters at the time, going abroad for the first time. Those players stuck with me. Besides, seniors like Vijay Manjrekar, Bapu Nadkarni and others also supported me. There were one or two voices that were sort of unhelpful.

Isn't there a serious case for giving captains and coaches more powers?

Yes, certainly. The captain needs the backing of the board. They should take him into confidence and tell him that we are giving you full charge, get these guys to perform or they are out. I was lucky I got the full backing of the board. But very often captains don't get that kind of backing, and they are hesitant to take strong steps and that hesitancy can be seen very easily in the dressing room. There has to be coordination and cooperation among the captain, board members and selectors.

Did you always get the team you wanted?

Oh, almost always. I got the XI I wanted. You have to make some compromises on the 14 to keep a few people happy. But that was okay. Except when Vijay Merchant was the chairman of selectors. He couldn't even explain why he wanted to change the team. If he had given proper reasons, people would have understood, but he had no reasons.

It was suggested that Merchant's animosity towards you was rooted in his differences with your father, and that he got even by using his casting vote to keep you out of the side in 1971.

I think he found fault with me from the beginning. And a lot of his decisions made no logical sense. I never got the impression it was because of my father; I think it was more personal. The moment I was gone, all the people I wanted in the side were back in the team. All the young fellows he had got when I was captain were gone and the senior players were brought back.

That leads to the question whether the captain should have a greater say in the team selection. Should he have a vote?

The captain's inputs must be seriously considered. And if a captain can have a good understanding with the selectors and reason things out with them, he can have the team he wants. That was true, by and large, in my experience. But no, the captain shouldn't have a vote. It could lead to serious acrimony.

Does a non-performing captain have a place in modern cricket?

I doubt it very much. Cricket has changed a lot in [recent times]. Not that the quality of cricketers is any better. You would not find an allrounder like Botham today or a fast bowler like [Fred] Trueman. But yes, it has become much more competitive and physically challenging. Not that you could carry a passenger even in those days. You had to contribute something and Brearley did contribute. A lot, in fact. He got Botham's act together. And Botham did play like six players put together in that series [1981 Ashes]. If a captain can do that he certainly deserves a place. So for Brearley to find a place in the side today, you first have to find a Botham.

What do you think Brearley did with Botham?

He talked to him, and he must have talked to him in a way Botham understood. A captain can't make a player perform beyond his ability. That's impossible. But very often, players are performing at only 50% of their ability. A good captain lifts that up to 80% and 90%. And I think Brearley got Botham to perform at 100%. That's phenomenal. I saw those matches. Botham was an inspired cricketer.

"Gavaskar brought pace bowling back into Indian cricket. Kapil's performance in his first few matches was terrible. But Gavaskar showed faith in him" © PA Photos

Going back to an earlier question: different players need to be handled differently. So obviously a captain has to be different things to different people.

Going back to an earlier question: different players need to be handled differently. So obviously a captain has to be different things to different people.

Of course. If a player had the kind of ability Botham had, you had to treat him specially. If you treated him like a mediocre cricketer, his performance would be mediocre. You had to give him a little more freedom.

If you were his captain, would you mind if he went to a nightclub the day before the match and came back at 12?

If he came back at 12, I would be very happy [laughs].

A captain can't create talent. But he can lift the spirit of an ordinary team. Motivation is very important. Without it, a good team can become very ordinary. Richie Benaud was a great motivator. He was a great performer himself, great bowler, brilliant fielder, and he had the team behind him. I got to know him very well because we sometimes shared a flat in London. He was the sort of captain whose very presence lifted the spirit of the team. Even when he was injured and not playing, his presence in the dressing room motivated his players.

What about Clive Lloyd? Some say he wasn't so good tactically.

That's because he didn't have to do any captaincy. But Lloyd's greatest contribution was his vision. He brought about the most radical tactical innovation when he decided to use four fast bowlers. It wasn't conventional thinking in those days. And he was hugely respected by his players.

Who would you rate as the best Indian captain after your era?

[Ajit] Wadekar had the results. But it has to be [Sunil) Gavaskar. He was as talented a player as Tendulkar and he had a very good cricket brain. He brought pace bowling back into Indian cricket.

In a sense, he was lucky to have Kapil Dev around.

He had to encourage Kapil Dev. Kapil's performance in his first few matches was terrible. But Gavaskar showed faith in him. He wanted a good new-ball attack, perhaps because he was an opening batsman. He saw the talent and he nurtured it. Some people call him a defensive captain, but you have to analyse the circumstances in which he led.

A good captain must have a fair idea about the limitations of his side. I know a lot of Tests are ending in results nowadays and plenty of risks are being taken. I have always believed that you should play to win, but the approach varies from individual to individual. In Test cricket, it sometimes makes sense to ensure that you don't lose the match. To me, one of Sunil's greatest contributions was that he brought professionalism to Indian cricket.