'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Thursday, 2 November 2023

Saturday, 28 November 2020

'Cleaning up Indian cricket is a lost cause' Ramachandra Guha

Social historian Ramachandra Guha can easily cast a spell on the listener with his deep knowledge and his spontaneity. Guha, who was briefly, in 2017, a member of the Committee of Administrators appointed by the Supreme Court of India to oversee reforms in the BCCI, has written a cricket memoir, The Commonwealth of Cricket that traces his relationship with the sport from the time he was four. He says it will be his last cricket book, but as he reveals in the following interview, he will continue his love affair with the game - despite the way it is administered in India. Courtesy Cricinfo

This is your first cricket book in nearly two decades, after A Corner of the Foreign Field was published in 2002. Why did you decide to write it now?

Two things. One, I wanted to pay tribute to my uncle Dorai, my first cricketing mentor and an exemplary coach and lover of the game, who is still active at the age of 84, running his club. I knew at some stage I would like to pay tribute to him.

Paying tribute to people I admire, respect, have been influenced by, is something I have done through my writing career. I have written about environmentalists, scholars, biographers, civil liberties activists. So I also wanted to write about this cricketer [Dorai] who had inspired me.

And I did my stint at the board. That kind of completed the journey from cricket-mad boy through player and writer and spectator to actually being inside the belly of the beast. So I thought that the arc is complete and maybe I should write a book.

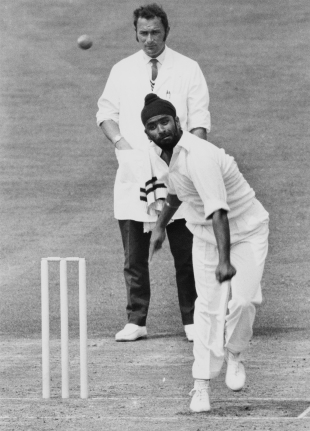

In the book you have defined four types of superstars: 1. Crooks who consort with and pimp for bigger non-cricket-playing crooks. 2. Those who are willing and keen to practise conflict of interest explicitly. 3. Those who will try to be on the right side of the law but stay absolutely silent on […] those in categories 1 and 2. 4. Those who are themselves clean and also question those in categories 1 and 2." Bishan Bedi, you say, is the only one you can think of in that last category. Why is that?

Because he is a person of enormous character, integrity and principle. He never equivocates, he never makes excuses. And he calls it as it is. These kinds of people are rare in public life in India. They are rare in the film world, they are rare in the business world, and virtually invisible in politics. They are rare also in journalism, if you go by the ways in which editors in Delhi, for many years, have been intrigued with politicians, sought Rajya Sabha seats or favours, houses for themselves…

To find someone like Bishan Bedi, who is ramrod straight in his conduct, in any sphere of public life in India today is increasingly rare. He is also an incredibly generous man. When I first met him, at my uncle's house for dinner, he gave a cricket bat to my uncle - because he never wants to take freebies.

Bishan always has given back much more to youngsters he has nurtured. He is very blunt, he is abrasive, like me. He makes enemies because he sometimes says things in an indiscreet or impolite way. But it's really the quality and calibre of his character that compels admiration in me today. When I was young, it was the art and beauty of his spin bowling. Today, it's the kind of man he is.

You write that the superstar culture "that afflicts the BCCI means that the more famous the player (former or present) the more leeway he is allowed in violating norms and procedures". How does that start?

Your question compels me to reflect on a time when players had too little power. When Bedi once gave a television interview where he said some sarcastic things, he was banned for a [Test] match in Bangalore in 1974. Players had to get more power, they had to get organised, they had to be noticed, they had to be paid properly, which took a very long time. The generation of Bedi and [Sunil] Gavaskar was not really paid well till the fag end of their careers.

But now to elevate them into demigods and icons… one of the things I talk about is [Virat] Kohli and [Anil] Kumble and their rift [Kumble was forced to step down as coach after the 2017 Champions Trophy]. How essentially Kohli had a veto over who could be his coach, which is not the case in any sporting team anywhere.

[MS] Dhoni had decided: I'm not going to play Test cricket. He was only playing one-day cricket. And I said [in the CoA] that he should not get a [Grade] A contract. Simple. That contract is for people who play throughout the year. He has said, "I'm not playing Test cricket." Fine. That's his choice and he can be picked for the shorter form if he is good enough. [They said] "No, we are too scared to demote him from A to B." And more than the board, the CoA, appointed by the Supreme Court, chaired by a senior IAS officer, was too scared. I thought it was hugely, hugely problematic. So I protested about it while I was there. And when I got nowhere, I wrote about it.

Is it the fans who create this culture?

Of course. They venerate cricketers. That's fine. Cricketers do things that they cannot do. It's the administrators who have to have a sense of balance and proportion. And not just with cricketing superstars who are active but also superstars who are retired. Again, to go back to one of the examples I talk about in my book: that [Rahul] Dravid could have an IPL contract, but other coaches in the NCA couldn't. Now, you can't have double standards like this. Cricket is supposed to be played with a straight bat.

It is not Dravid's fault. He just used the rules as they existed for him. It was the fault of the BCCI management that it created this kind of division and caste system within cricketers, within coaches, within umpires, within commentators. It offended my ethical sensibilities. So I protested.

You recently told Mid-Day that "N Srinivasan and Amit Shah are effectively running Indian cricket today".

It is true.

Are they really running the board?

Yeah, that's my sense. Along with their sons and daughters and sycophants. That's what it is. And [Sourav] Ganguly [the BCCI president] has capitulated. I mean, there are things he should not be doing, given his extraordinary playing record and his credibility, whether he should be practising this shocking conflict of interest. The kind of example it sets is abysmal. I say this with some sadness because I admired Ganguly as a cricketer and as a captain. I'm glad I'm out of it and I'm just a fan again. I can just enjoy the game and not bother about the murkiness within the administration.

Things were meant to change under Ganguly.

Again, I go back to what I said about Bedi: people of principle are rare in any walk of life. And in India, particularly, there is a temptation for fame, for glory, to cosy up to who's powerful. It's very, very, very sad, but it happens. Maybe it's something to do with a deep flaw in our national character, that we lack a backbone in these matters.

In the book, where you address the topic across two chapters, as well as during your tenure in the CoA, you say you were frustrated by how deep the roots of conflict of interest have grown, not just in the BCCI and state associations but also across the player fraternity. Why is it so difficult for both administrators and players, some of whom are former greats, to understand conflict?

Because it's ubiquitous and everybody is practising it. Woh bhi kar raha hai, main bhi karoonga. Kya hai usme? [He's doing it, so I'll also do it. What's the big deal?] It's hard to resist, you know, especially [when] the moral compass of people around you is so low that you just kind of go along with it.

Sunil Gavaskar is another person who said had multiple conflict of interests.

To Dravid's credit, he saw the point and gave up his Delhi Daredevils contract relatively quickly. He exploited the rules as they were and once I protested and it became public, he realised that he had probably erred and done a wrong thing. Maybe Ganguly could have learned from Dravid in what he's doing now. Cleaning up Indian cricket is a lost cause.

In 2018, the Supreme Court modified its original order of 2016, passed by Chief Justice TS Thakur concerning the Lodha reforms. In 2019, immediately after taking over, Ganguly's administration asked the court to relax key reforms, which would virtually wipe out the reforms. Is it now the responsibility of the court to decisively put the lid on the case?

I'm not losing any sleep. Cricket lovers have to live with a corrupt and nepotistic mode. We should just move on and enjoy the cricket.

In the book, you say you write on history for a living and on cricket to live. Can you tell us a bit more about that?

When I started writing this book, I had just finished the second volume of my Gandhi biography. It's a thousand pages long, inundated with millions of footnotes. And when you write a properly researched work of history, you have to have your sources at hand. So you compile a paragraph, which is based on material you gather, and then you have to scrupulously footnote that paragraph. One paragraph may be drawn from four different sources - a newspaper, an archival document, a book - and you have to put all that in.

Whereas I wanted to write this freely and spontaneously. I could only do that in the form of cricket memoir. So that's how it happened. I wanted a release from densely footnoted, closely argued, scrupulously researched scholarly work. And this came as a kind of liberation.

You call yourself a cricket fanatic. For me, on reading the book, it's the romantic in you that comes to life.

Yeah, I think I am more a romantic than a fanatic. I'm cricket-obsessed. I've been cricket-obsessed all my life, but more in a romantic way; "fanatic" may be slightly wrong because that assumes you always want your team to win. And that's certainly not the case with me anymore.

You write in the book about a fanboy moment you had: "On this evening I did something I almost never do - take a selfie, with Bishan Bedi and the coach of the Indian team, Anil Kumble." Can you recount that incident?

It was the BCCI's annual function. One of the few things I was able to do in my brief tenure at the board was accomplished on that day: to have [Padmakar] Shivalkar and [Rajinder] Goel, two great left-arm spinners, get the CK Nayudu [Lifetime Achievement] Award - the first time a non-Test cricketer had been honoured. And also to have Shanta Rangaswamy get the first Lifetime Achievement Award for Women.

So it was a happy occasion. It was in my home town [Bengaluru]. Bishan had come from Delhi. Kumble was then the coach of the [Indian] team. I know Bishan well and Anil a little bit. I don't know that many cricketers, actually. All these years running about the game, my only friend is really Bishan Bedi, apart from Arun Lal, who was my college captain.

Kumble, of course, would admire Bishan as a kind of sardar [chief] of Indian spin bowling. I saw them and I said I'll take a selfie. What I don't mention is that the selfie was taken by Anil, because he is technologically much more sophisticated than either Bishan or me. He took that selfie very artfully, which I would not have been able to do. It came out nicely. It is the only photograph in the book.

I am a partisan of bowlers and of spin bowlers. For me, Kumble has always been underappreciated as a cricketer. To win a Test match you need to take 20 wickets. And, arguably, Kumble has therefore won more Test matches than Sachin Tendulkar. As I again say in the book, in 1999, when Tendulkar was about to be replaced as captain, they should really have had Kumble - he is a masterful cricketing mind, but there is a prejudice against bowlers. So in a sense, [the photo was with] someone who was a generation older than me, Bedi, and someone of a generation younger than me, Kumble - both cricketers I admire, both with big hearts, and both spin bowlers, as I was myself.

That's why the caption says: "two great spin bowlers and another" - kind of implying I was a spin bowler, but a rather ordinary one.

Is it true that this possibly could be your last cricket book?

Almost certainly. It would be, because I really have nothing else to say. This is a kind of cricketing autobiography and it has covered a lot. This is my fourth cricket book. I will watch the game. I will appreciate it.

Why don't more Indian cricketers write books?

I think Dravid has a great book in him because he is a thinking cricketer. So might Kumble. But my suspicion is, Kumble will not write a book. Dravid just might. He could write a book called The Art of Batsmanship. Bedi could have written a book because he is an intelligent person. He writes interesting articles, including on politics and public life. By the way, books don't sell. That's another reason. Occasionally, cricketers have thought, I will write a book and I will make Rs 30-40 lakhs (about US$50,000) on it. But cricket books don't really make that much money.

Thursday, 29 January 2015

The emirate of Indian cricket and its subjects

Mukul Kesavan in Cricinfo

What sort of cricketing culture sees conflict of interest as normal? The answer lies in the history of cricket administration in India.

Long-time observers of the BCCI know that it used to be cricket's answer to the medieval city state. No Medici controlled Florence as comprehensively as the BCCI controlled cricket in India. The Board of Control was an independent principality, located in India, surrounded by India, but not of India. Its jurisdiction over cricket in India was as absolute as the Vatican's over Catholicism; it brooked no interference in its affairs, not even from the nation state that enclosed it.

Its last pope showed his cardinals that he was the god of most things by turning conductor and orchestrating a symphony of conflicting interests. His orchestra pit was crowded with cricketers, ex-cricketers, captains, captains of industry, consultants, commentators, cooing starlets, all on the same page, bobbing to his baton. During his reign most living things in cricket's jungle became the board's creatures, bound by contract, muted by money and sworn to servility. Not everyone: the Great Indian Bedi, never a herd animal, wouldn't be corralled, but he was an exception. Most errant beasts that held out were forced back into the fold by the threat of excommunication. In the context of the godless present this meant not the eternal absence of the Lord's grace, but the permanent loss of the board's cash.

The board's independence was secured not by defying Leviathan but by co-opting it. Sharad Pawar, Arun Jaitley, Rajeev Shukla, even Narendra Modi, have all helped administer cricket in India. Unluckily for the BCCI, the Supreme Court couldn't be squared, and so this cricketing emirate with Dubai's soul and Abu Dhabi's reserves finds itself in danger of being regulated like a public sector undertaking.

The recent Supreme Court ruling got one thing exactly right: Indian cricket's original sin was the amendment of the virtuous clause in the BCCI's constitution that barred its office holders from taking a financial stake in any matches or tournaments organised by the board. It was this (retrospective) amendment that allowed N Srinivasan, then treasurer of the BCCI, to buy an IPL franchise, Chennai Super Kings. The conflict of interest that this created - especially after Srinivasan rose to become the president of the BCCI - was so enormous, so brazen, so perversely exemplary, that people involved with cricket's economy felt free to wallow in their own, smaller, conflicts.

One of the board's many apologists, appearing on a televised discussion of the Supreme Court's intervention, ingeniously cited the many conflicts of interest that Srinivasan's example had engendered, to normalise his own. If men like MS Dhoni and Rahul Dravid could hold sinecures at India Cements while captaining teams in the IPL, why were people so exercised about Srinivasan's double role?

The short answer to this is that a) Srinivasan's position as Indian cricket's primate and CSK's boss made his conflicts of interest a systemic threat to the health of Indian cricket, and b) Srinivasan's conflicts created an actual, not theoretical, crisis of credibility for Indian cricket. But it's worth taking the apologist's question seriously and supplying a longer answer to understand the cricketing culture that allowed these conflicts of interest to seem normal, even legitimate.

While trying to understand Indian cricket's deafness to the notion of a conflict of interest, it's useful to bear in mind a historical fact: the BCCI transitioned from an oligarchy of patrons to an oligarchy of rentiers and entrepreneurs inside 20 years.

Nominally, the BCCI presides over a pyramidal system of cricket administration based on indirect election. In actual fact most electoral colleges are owned by local grandees. Often a business family will dominate the local cricket association for decades. The elections that legitimise the present system have more in common with the politics of rigged pocket boroughs in 18th-century England than the broad democracy of republican India. Elections to the BCCI, the apex body of Indian cricket, are often accompanied by a chorus of allegations about rigging, gerrymandering and accreditation.

The BCCI is run by a cabal of colonial-style patrons. This self-perpetuating clique struck oil less than 20 years ago. It recognised the potential of revenue streams created by economic liberalisation and successfully connected an opaque club of amateur administrators with real money. The coming of cable television and the consolidation of a national television audience created the revenues that underwrote the first generation of endorsement superstars: Kapil Dev, Azharuddin, Tendulkar. Once, Doordarshan telecast cricket as a kind of republican duty to India's cricket-mad citizens; then private television channels learnt it was a privilege for which they had to pay vast sums.

The game was so comprehensively monetised that the BCCI began demanding fees to permit the photographing of matches and the broadcasting of radio commentary. The idea that cricket was news or even that it was an event in the real world that could be reported on, gratis, gave way to the idea that cricket was proprietary entertainment that could only be captured in pictures or the spoken word for a fee. ESPNcricinfo briefly stopped calling IPL teams by their franchise names because it was advised that these names were commercial properties that couldn't be used without payment.

With us or against us: the BCCI had the last laugh when Kapil Dev chose to side with the rebel ICL © AFP

With us or against us: the BCCI had the last laugh when Kapil Dev chose to side with the rebel ICL © AFPThe monetising of cricket occurred within an administrative culture where the BCCI's officials still saw themselves as "honorary" patrons. Before the boom these men had leveraged their status as cricket's patrons into social standing as city grandees. For ex-rajas and aspirational businessmen - traditionally, big business didn't bother with cricket - cricket was a way of being someone on the regional or national stage.

N Srinivasan's back story fits the model. He ran India Cements, he was genuinely interested in sport and he was a pillar of Madras society. For him, as for the Rungtas in Rajasthan or Dalmiya in Bengal, cricket was a route to social consequence and the public eye. In Madras, Srinivasan was preceded as patron by two other industrialists, AC Muthiah and his father MA Chidambaram, after whom the stadium at Chepauk is named. It's important to recognise that men like Chidambaram, Muthiah and Srinivasan didn't make money out of the game before the boom. They actually spent their own money subsidising cricketers and cricket because this was what patrons did.

In this way the men who governed Indian cricket came to see themselves as benefactors and the men who played cricket in India learnt to recognise them as such. Through the long shamateur epoch of Indian cricket, cricketers were supported by sinecures in private companies and public sector undertakings, and socialised into the role of dependent clients. It was a recognition forced upon them by the need to make a living in a sport that had no business model and generated no money.

These patron-client relationships survived the monetisation of Indian cricket, which happened, it's worth remembering, with bewildering speed. Even after successful cricketers became rich men, members of a sporting super elite, they went along with being infantilised as clients. There were three broad reasons for this.

One, gratitude. They remembered the hard times and were grateful for the support that patrons like Srinivasan had extended to the sport. India Cements had dozens of players on its rolls. It supported league cricket in Madras and helped players - not necessarily international players - make a living. (It wasn't alone in this. Sungrace Mafatlal supported cricket generously in Bombay; Sachin Tendulkar joined its Times Shield team in 1990 after his Test debut. It is something of an irony that this fabric brand didn't survive the economic liberalisation that helped make both Tendulkar and the BCCI fabulously wealthy.)

Three, fear. To annoy the BCCI was to be exiled from Indian cricket and its economy; it was much safer to acknowledge the power of these "honorary" patrons than to be your own man. Here the ruthless purge of the Indian Cricket League rebels was the cautionary tale. A board that could unperson Kapil Dev, arguably the greatest Indian cricketer of the television age, for daring to dabble in an unauthorised league, was not to be crossed.

Thus, administrators like Srinivasan, persuaded of their virtue because of their generosity as patrons, were consumed by a sense of entitlement that made the very suggestion of a conflict of interest an impertinence. And players, used to deferring to patrons who made their livelihoods possible, found it hard to break the habit of clientage even when they didn't need the money. The idea that a sinecure might constitute a conflict of interest must have seemed preposterous: how could something endorsed by Srinivasan, uber-patron and undisputed master of the cricketing universe, be wrong?

Now that the Supreme Court has ruled that he was wrong, that there is such a thing as a conflict of interest and that the amendment of rule 6.2.4 was illegal, Indian cricket's supple auxiliaries have started airing their doubts about Srinivasan. The ex-player, the ex-IPL franchise manager, the marketing consultant, the sports management agent, the plausible commentator, have begun shyly sharing their long-brewed conviction that something was amiss. Shyly, because it isn't yet clear that the sheikh is dead, and given Srinivasan's past resilience who can blame them?

Will Indian cricket be regulated into virtue by the Supreme Court? It's hard to tell. But we do know that a precedent has been laid down by the court: the judiciary has stepped in and taken charge of the affairs of the BCCI. It has dismissed the BCCI's claim of being a private body. It has amended the BCCI's constitution, instructed Srinivasan to either sell CSK or withdraw from board elections, and assigned the reform of the board to a committee of three retired judges. It'll be a nice irony if the crony capitalism of this cabal becomes the proximate cause of a creeping nationalisation of Indian cricket.

Sunday, 26 May 2013

Cricket - Playing on a rotten wicket

Saturday, 11 August 2012

I is the most important letter in a cricket team

Friday, 11 September 2009

When trickery was afoot

| ||

| Every ball was a head-scratcher in itself: furious thinking would ensue as one tried to place it in a pattern initiated overs ago. Or was a new sequence of trickery starting with it? Now, was that a set-up ball, or just a bad one? Or was it just an innocent bridge piece in the composition before the cymbal crash came, causing the batsman to walk back? | |||

You have to be trusted by the people that you lie to,

So that when they turn their backs on you,

You get the chance to put the knife in.

- "Dogs", Roger Waters (Pink Floyd)

| ||

New! Receive and respond to mail from other email accounts from within Hotmail Find out how.