Martin Wolf in The Financial Times

The 75th anniversary of the defeat of Nazi Germany was May 8. The 70th anniversary of the Schuman declaration, which launched postwar European integration, was May 9. Just days before both, the German constitutional court launched a legal missile into the heart of the EU. Its judgment is extraordinary. It is an attack on basic economics, the central bank’s integrity, its independence and the legal order of the EU.

The court ruled against the ECB’s public sector purchase programme, launched in 2015. It did not argue that the ECB had improperly engaged in monetary financing, but rather that it had failed to apply a “proportionality” analysis, when assessing the impact of its policies, on a litany of conservative concerns: “public debt, personal savings, pension and retirement schemes, real estate prices and the keeping afloat of economically unviable companies”.

Monetary policies are necessarily economic policies. But the ECB’s policies, including asset purchases, are justified by the fact that it was — and is — failing to achieve its treaty-mandated “primary objective”, which is “price stability” defined as inflation “below, but close to, 2 per cent over the medium-term”. The EU treaty says other considerations are secondary.

The court also decreed that “German constitutional organs and administrative bodies”, including the Bundesbank, may not participate in ultra vires acts (those outside one’s legal authority). Thus, the Bundesbank may not continue to participate in the ECB’s asset purchase programmes, until the ECB has conducted a “proportionality assessment” satisfactory to the court.

Yet the EU treaty states that “neither the ECB, nor a national central bank . . . shall seek or take instructions . . . from any government of a member state or from any other body [my emphases].” The court’s instruction puts the Bundesbank into a conflict of laws.

The court is also assailing the right of the ECB to make its policy decisions independently. Germany fought hard to install central bank independence within the monetary union. Now, its constitutional court has decreed that unless the ECB satisfies the justices that it has taken full account of a highly political list of side-effects of monetary policies, asset purchases are impermissible. Courts in other member countries may see fit to decree that their national central banks cannot participate in policies they dislike. Pretty soon, the ECB will have been sliced and diced into a nullity.

Above all, the German court decreed that it can ignore an earlier ruling of the European Court of Justice in favour of the ECB, because the former “exceeds its judicial mandate . . . where an interpretation of the Treaties is not comprehensible and must thus be considered arbitrary from an objective perspective.” This is an act of judicial secession.

The EU is an integrated legal system, or it is nothing. It rests on the acceptance by all member states of its authority in areas of its competence. In a press release after the constitutional court’s judgment, the ECJ rightly responded that “the Court of Justice alone . . . has jurisdiction to rule that an act of an EU institution is contrary to EU law. Divergences between courts of the member states as to the validity of such acts would indeed be liable to place in jeopardy the unity of the EU legal order and to detract from legal certainty.” Imagine if the courts of every member state were able to decide that ECJ rulings were “arbitrary from an objective perspective”.

What are the implications?

If the German court is ultimately satisfied that the ECB adequately assessed the economic impact of its purchases, the PSPP might continue. But the courthas reduced the ECB’s future flexibility by limiting its holdings of any member country’s debt to 33 per cent of the outstanding total and insisting that asset purchases be allocated according to member states’ shares in the ECB.

In the absence of other eurozone support programmes, the chance of defaults has jumped. Indeed, spreads on Italian government bonds have duly risen a little since the court’s announcement. A crisis might ultimately ensue, with devastating effects; perhaps even a break-up of the eurozone.

Others might follow Germany in rejecting the jurisdiction of the ECJ and EU. Hungary and Poland are obvious candidates. Future historians may mark this as the decisive turning point in Europe’s history, towards disintegration.

What can be done? The ECB cannot be accountable to a national court. But the Bundesbank could provide the court with the proportionality analysis. Maybe that would be enough, albeit also a bad precedent. Or, the decision could be ignored. If a German court can ignore the ECJ, maybe the Bundesbank can ignore that court. Alternatively, the ECB could just abandon efforts to rescue the eurozone and accept whatever outcome emerges.

The EU could initiate an infringement proceeding against Germany. But its direct target would be the German government, which is caught between the EU organs on the one hand and the court on the other. It could not change the ruling.

More radically, the EU could act to create the needed degree of fiscal solidarity. But the obstacles to this are large. A new treaty looks out of the question in today’s environment of intense mutual distrust. Finally, Germany could boldly secede from the eurozone. Yet, before it makes such a decision, one hopes it, too, will be required to do a full analysis of whether that would be “proportionate”.

One point is clear: The constitutional court has decreed that Germany, too, can take back control. As a result it has created a possibly insoluble crisis.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label disintegration. Show all posts

Showing posts with label disintegration. Show all posts

Wednesday, 13 May 2020

Saturday, 11 February 2017

The case for sledging

Sam Perry in Cricinfo

Around a decade ago a 20-year-old man walked to a suburban wicket with his team in a precarious position. The previous week they had conceded a glut of runs to a rampaging opposition that included a recently discarded international player. In a message to selectors and anyone else who wanted to listen, the deposed veteran made a score that dropped jaws.

And so the 20-year-old strode to the crease, his team 40 for 4 in reply. Two overs remained before lunch. Slightly shaking but presenting the bravest face possible, he asked for centre. In an attempt at familiarity, he addressed the umpire by name. It was a disastrous overcompensation, seized upon gleefully.

"Do you know him, mate?" offered the point fieldsman. Chuckles ensued from those in earshot. The batsman glanced behind him to see four slips waiting. Each stared, stony-faced, directly back. Two had arms folded, two had hands behind their backs, like policemen strolling their beat. Robocop wraparound sunglasses were the day's fashion, as was the gnashing of chewing gum. The batsman probably shouldn't have addressed the umpire by name. It played on his mind.

"Rod, do you know this bloke?" came the follow-up from first slip. It was the veteran record-breaker, speaking to the umpire, capitalising on the moment. All heads turned to the man in white, now a central character in the contrived pantomime. Rod chuckled. "Nope!" he replied, followed by more laughter. A ball hadn't yet been bowled.

The veteran continued, "Mate, what's going on with your socks?" Now we had a problem. Unbeknown to the batsman, he had tucked his socks into his pants before affixing his pads. "Is this Under-12s? Rod, am I playing Under-12s?" Guffaws followed from all but the already humiliated batsman. He was out for 5, caught at gully off the last ball before lunch.

Sledging has utility and that's primarily why it exists. While few of us ever will, were we to step into the private confines of a professional dressing room, we would likely find believers. You won't hear this publicly, though, as the word itself has become villainous to cricketing morality. Very few are willing to openly defend sledging, though many privately believe in its value. Pragmatism often trumps principle.

So in this Trumpian world, perhaps it's time to air the views of a silent majority. Maybe sledging is effective. Maybe sledging makes a difference. Maybe sledging helps teams win.

We accept that cricket is a mental game, and let's face it, the majority of us cannot control ourselves very well mentally

Contrary to popular conception, sledging is rarely a series of witty one-liners of the sort found in internet listicles. Nor is it often outright verbal abuse. In large part it's merely a stream of hushed expletives, passive-aggressive body language, conversations between team-mates, and assorted noises, the worst of which is laughter.

We accept that cricket is a mental game, and let's face it, the majority of us cannot control ourselves very well mentally. We are not purveyors of unadulterated Zen and focused positivity. We are mostly flawed individuals, who carry our nerves, insecurities and awareness of weakness into most of life's important moments. We all learned at an early age that humiliation, embarrassment, and feelings of not belonging compromise our confidence. Ergo, if you accept that confidence is critical to cricketing success, then isn't it the opposition's imperative to weaken it?

Which brings us to sledging's ethical considerations. Among the many and overlapping guiding principles for a player's behaviour, particularly at the professional level, standing as tall as any is this: "What will help us win?" It's here that we confront sledging's mythical line. For most, the line is simply about what you can get away with. Or as Nathan Lyon described it, "We try to head-butt the line." If there is an upside or edge to be exploited in pursuit of victory, aren't players arguably justified in doing so? When it comes to sledging, for many the question is less "Is this right?", more "Will this work?"

Of course, it doesn't always work. Some personalities thrive under sledging, while others are immune. But these are rare birds. It's more likely than not that sledging hurts us. If we succeed, we do so in spite of it and not because of it. And so in our new, Trump-led world, where the prevailing doctrines seem to be less about honour and more about winning, it is fitting to view sledging as a viable tool in the arsenals of fielding sides. No one will say so, mind.

Beyond its capacity to mentally disrupt the opposition, in some countries sledging seemingly has a cultural allure too. You don't have to travel far on YouTube to witness the bipartisan adoration for former Australian prime minister Paul Keating, whose ability to deliver withering verbal takedowns and comebacks is arguably without peer. He is adored for his capacity to verbally undermine his opposition, and it's understandable that many may seek to emulate that when it comes to facing opponents of their own.

This potent yet fragile tool for psychological disruption remains as alive as ever. Ask any batsman whether they'd prefer to be sledged when they bat or not, and the honest answer will be no. And it is for this reason that they will engage in sledging themselves when fielding. While many might express a glib, deep-voiced indifference to "chat", we would all much prefer friendly, welcoming, encouraging environs when out in the middle. The reality, however sad or unethical, is that sledging usually makes one's innings more difficult. So long as professional pragmatism and the doctrine of winning prevails, so will sledging, whether publicly acknowledged or not.

Around a decade ago a 20-year-old man walked to a suburban wicket with his team in a precarious position. The previous week they had conceded a glut of runs to a rampaging opposition that included a recently discarded international player. In a message to selectors and anyone else who wanted to listen, the deposed veteran made a score that dropped jaws.

And so the 20-year-old strode to the crease, his team 40 for 4 in reply. Two overs remained before lunch. Slightly shaking but presenting the bravest face possible, he asked for centre. In an attempt at familiarity, he addressed the umpire by name. It was a disastrous overcompensation, seized upon gleefully.

"Do you know him, mate?" offered the point fieldsman. Chuckles ensued from those in earshot. The batsman glanced behind him to see four slips waiting. Each stared, stony-faced, directly back. Two had arms folded, two had hands behind their backs, like policemen strolling their beat. Robocop wraparound sunglasses were the day's fashion, as was the gnashing of chewing gum. The batsman probably shouldn't have addressed the umpire by name. It played on his mind.

"Rod, do you know this bloke?" came the follow-up from first slip. It was the veteran record-breaker, speaking to the umpire, capitalising on the moment. All heads turned to the man in white, now a central character in the contrived pantomime. Rod chuckled. "Nope!" he replied, followed by more laughter. A ball hadn't yet been bowled.

The veteran continued, "Mate, what's going on with your socks?" Now we had a problem. Unbeknown to the batsman, he had tucked his socks into his pants before affixing his pads. "Is this Under-12s? Rod, am I playing Under-12s?" Guffaws followed from all but the already humiliated batsman. He was out for 5, caught at gully off the last ball before lunch.

Sledging has utility and that's primarily why it exists. While few of us ever will, were we to step into the private confines of a professional dressing room, we would likely find believers. You won't hear this publicly, though, as the word itself has become villainous to cricketing morality. Very few are willing to openly defend sledging, though many privately believe in its value. Pragmatism often trumps principle.

So in this Trumpian world, perhaps it's time to air the views of a silent majority. Maybe sledging is effective. Maybe sledging makes a difference. Maybe sledging helps teams win.

We accept that cricket is a mental game, and let's face it, the majority of us cannot control ourselves very well mentally

Contrary to popular conception, sledging is rarely a series of witty one-liners of the sort found in internet listicles. Nor is it often outright verbal abuse. In large part it's merely a stream of hushed expletives, passive-aggressive body language, conversations between team-mates, and assorted noises, the worst of which is laughter.

We accept that cricket is a mental game, and let's face it, the majority of us cannot control ourselves very well mentally. We are not purveyors of unadulterated Zen and focused positivity. We are mostly flawed individuals, who carry our nerves, insecurities and awareness of weakness into most of life's important moments. We all learned at an early age that humiliation, embarrassment, and feelings of not belonging compromise our confidence. Ergo, if you accept that confidence is critical to cricketing success, then isn't it the opposition's imperative to weaken it?

Which brings us to sledging's ethical considerations. Among the many and overlapping guiding principles for a player's behaviour, particularly at the professional level, standing as tall as any is this: "What will help us win?" It's here that we confront sledging's mythical line. For most, the line is simply about what you can get away with. Or as Nathan Lyon described it, "We try to head-butt the line." If there is an upside or edge to be exploited in pursuit of victory, aren't players arguably justified in doing so? When it comes to sledging, for many the question is less "Is this right?", more "Will this work?"

Of course, it doesn't always work. Some personalities thrive under sledging, while others are immune. But these are rare birds. It's more likely than not that sledging hurts us. If we succeed, we do so in spite of it and not because of it. And so in our new, Trump-led world, where the prevailing doctrines seem to be less about honour and more about winning, it is fitting to view sledging as a viable tool in the arsenals of fielding sides. No one will say so, mind.

Beyond its capacity to mentally disrupt the opposition, in some countries sledging seemingly has a cultural allure too. You don't have to travel far on YouTube to witness the bipartisan adoration for former Australian prime minister Paul Keating, whose ability to deliver withering verbal takedowns and comebacks is arguably without peer. He is adored for his capacity to verbally undermine his opposition, and it's understandable that many may seek to emulate that when it comes to facing opponents of their own.

This potent yet fragile tool for psychological disruption remains as alive as ever. Ask any batsman whether they'd prefer to be sledged when they bat or not, and the honest answer will be no. And it is for this reason that they will engage in sledging themselves when fielding. While many might express a glib, deep-voiced indifference to "chat", we would all much prefer friendly, welcoming, encouraging environs when out in the middle. The reality, however sad or unethical, is that sledging usually makes one's innings more difficult. So long as professional pragmatism and the doctrine of winning prevails, so will sledging, whether publicly acknowledged or not.

Saturday, 25 June 2016

Brexit won’t shield Britain from the horror of a disintegrating EU

Yannis Varoufakis in The Guardian

Leave won because too many British voters identified the EU with authoritarianism, irrationality and contempt for parliamentary democracy while too few believed those of us who claimed that another EU was possible.

I campaigned for a radical remain vote reflecting the values of our pan-European Democracy in Europe Movement (DiEM25). I visited towns in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, seeking to convince progressives that dissolving the EU was not the solution. I argued that its disintegration would unleash deflationary forces of the type that predictably tighten the screws of austerity everywhere and end up favouring the establishment and its xenophobic sidekicks. Alongside John McDonnell, Caroline Lucas, Owen Jones, Paul Mason and others, I argued for a strategy of remaining in but against Europe’s established order and institutions.

‘The markets will soon settle down, and negotiations will probably lead to something like a Norwegian solution that allows the next British parliament to carve out a path toward some mutually agreed arrangement.’ Photograph: Leon Neal/AFP/Getty Images

The only man with a plan is Germany’s finance minister. Schäuble recognises in the post-Brexit fear his great opportunity to implement a permanent austerity union. Under his plan, eurozone states will be offered some carrots and a huge stick. The carrots will come in the form of a small eurozone budget to cover, in some part, unemployment benefits and bank deposit insurance. The stick will be a veto over national budgets.

If I am right, and Brexit leads to the construction of a permanent austerian iron cage for the remaining EU member states, there are two possible outcomes: One is that the cage will hold, in which case the institutionalised austerity will export deflation to Britain but also to China (whose further destabilisation will have secondary negative effects on Britain and the EU).

Another possibility is that the cage will be breached (by Italy or Finland leaving, for instance), the result being Germany’s own departure from the collapsing eurozone. But this will turn the new Deutschmark zone, which will probably end at the Ukrainian border, into a huge engine of deflation (as the new currency goes through the roof and German factories lose international markets). Britain and China had better brace themselves for an even greater deflation shock wave under this scenario.

The horror of these developments, from which Britain cannot be shielded by Brexit, is the main reason why I, and other members of DiEM25, tried to save the EU from the establishment that is driving Europeanism into the ground. I very much doubt that, despite their panic in Brexit’s aftermath, EU leaders will learn their lesson. They will continue to throttle voices calling for the EU’s democratisation and they will continue to rule through fear. Is it any wonder that many progressive Britons turned their back on this EU?

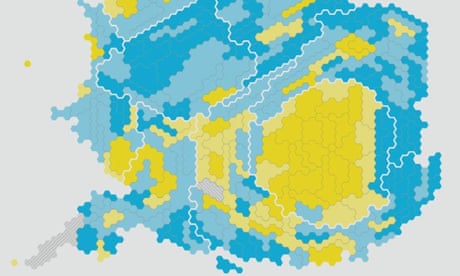

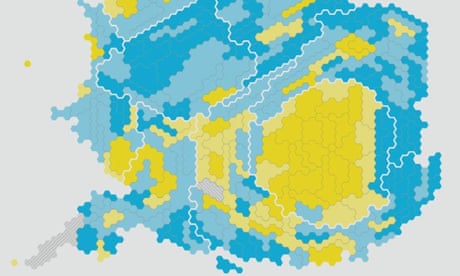

EU referendum full results – find out how your area voted

While I remain convinced that leave was the wrong choice, I welcome the British people’s determination to tackle the diminution of democratic sovereignty caused by the democratic deficit in the EU. And I refuse to be downcast, even though I count myself on the losing side of the referendum.

As of today, British and European democrats must seize on this vote to confront the establishment in London and Brussels more powerfully than before. The EU’s disintegration is now running at full speed. Building bridges across Europe, bringing democrats together across borders and political parties, is what Europe needs more than ever to avoid a slide into a xenophobic, deflationary, 1930s-like abyss.

Leave won because too many British voters identified the EU with authoritarianism, irrationality and contempt for parliamentary democracy while too few believed those of us who claimed that another EU was possible.

I campaigned for a radical remain vote reflecting the values of our pan-European Democracy in Europe Movement (DiEM25). I visited towns in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, seeking to convince progressives that dissolving the EU was not the solution. I argued that its disintegration would unleash deflationary forces of the type that predictably tighten the screws of austerity everywhere and end up favouring the establishment and its xenophobic sidekicks. Alongside John McDonnell, Caroline Lucas, Owen Jones, Paul Mason and others, I argued for a strategy of remaining in but against Europe’s established order and institutions.

Against us was an alliance of David Cameron (whose Brussels’ fudge reminded Britons of what they despise about the EU), the Treasury (and its ludicrous pseudo-econometric scare-mongering), the City (whose insufferable self-absorbed arrogance put millions of voters off the EU), Brussels (busily applying its latest treatment of fiscal waterboarding to the European periphery), Germany’s finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble (whose threats against British voters galvanised anti-German sentiment), France’s pitiable socialist government, Hillary Clinton and her merry Atlanticists (portraying the EU as part of another dangerous “coalition of the willing") and the Greek government (whose permanent surrender to punitive EU austerity made it so hard to convince the British working class that their rights were protected by Brussels).

The repercussions of the vote will be dire, albeit not the ones Cameron and Brussels had warned of. The markets will soon settle down, and negotiations will probably lead to something like a Norwegian solution that allows the next British parliament to carve out a path toward some mutually agreed arrangement. Schäuble and Brussels will huff and puff but they will, inevitably, seek such a settlement with London. The Tories will hang together, as they always do, guided by their powerful instinct of class interest. However, despite the relative tranquillity that will follow on from the current shock, insidious forces will be activated under the surface with a terrible capacity for inflicting damage on Europe and on Britain.

Italy, Finland, Spain, France, and certainly Greece, are unsustainable under the present arrangements. The architecture of the euro is a guarantee of stagnation and is deepening the debt-deflationary spiral that strengthens the xenophobic right. Populists in Italy and Finland, possibly in France, will demand referendums or other ways to disengage.

The repercussions of the vote will be dire, albeit not the ones Cameron and Brussels had warned of. The markets will soon settle down, and negotiations will probably lead to something like a Norwegian solution that allows the next British parliament to carve out a path toward some mutually agreed arrangement. Schäuble and Brussels will huff and puff but they will, inevitably, seek such a settlement with London. The Tories will hang together, as they always do, guided by their powerful instinct of class interest. However, despite the relative tranquillity that will follow on from the current shock, insidious forces will be activated under the surface with a terrible capacity for inflicting damage on Europe and on Britain.

Italy, Finland, Spain, France, and certainly Greece, are unsustainable under the present arrangements. The architecture of the euro is a guarantee of stagnation and is deepening the debt-deflationary spiral that strengthens the xenophobic right. Populists in Italy and Finland, possibly in France, will demand referendums or other ways to disengage.

‘The markets will soon settle down, and negotiations will probably lead to something like a Norwegian solution that allows the next British parliament to carve out a path toward some mutually agreed arrangement.’ Photograph: Leon Neal/AFP/Getty Images

The only man with a plan is Germany’s finance minister. Schäuble recognises in the post-Brexit fear his great opportunity to implement a permanent austerity union. Under his plan, eurozone states will be offered some carrots and a huge stick. The carrots will come in the form of a small eurozone budget to cover, in some part, unemployment benefits and bank deposit insurance. The stick will be a veto over national budgets.

If I am right, and Brexit leads to the construction of a permanent austerian iron cage for the remaining EU member states, there are two possible outcomes: One is that the cage will hold, in which case the institutionalised austerity will export deflation to Britain but also to China (whose further destabilisation will have secondary negative effects on Britain and the EU).

Another possibility is that the cage will be breached (by Italy or Finland leaving, for instance), the result being Germany’s own departure from the collapsing eurozone. But this will turn the new Deutschmark zone, which will probably end at the Ukrainian border, into a huge engine of deflation (as the new currency goes through the roof and German factories lose international markets). Britain and China had better brace themselves for an even greater deflation shock wave under this scenario.

The horror of these developments, from which Britain cannot be shielded by Brexit, is the main reason why I, and other members of DiEM25, tried to save the EU from the establishment that is driving Europeanism into the ground. I very much doubt that, despite their panic in Brexit’s aftermath, EU leaders will learn their lesson. They will continue to throttle voices calling for the EU’s democratisation and they will continue to rule through fear. Is it any wonder that many progressive Britons turned their back on this EU?

EU referendum full results – find out how your area voted

While I remain convinced that leave was the wrong choice, I welcome the British people’s determination to tackle the diminution of democratic sovereignty caused by the democratic deficit in the EU. And I refuse to be downcast, even though I count myself on the losing side of the referendum.

As of today, British and European democrats must seize on this vote to confront the establishment in London and Brussels more powerfully than before. The EU’s disintegration is now running at full speed. Building bridges across Europe, bringing democrats together across borders and political parties, is what Europe needs more than ever to avoid a slide into a xenophobic, deflationary, 1930s-like abyss.

Sunday, 24 May 2015

Arjuna Ranatunga - Large and in charge

Defiant, passionate, cunning - Arjuna Ranatunga was a mighty tough cookie on the field and an unwavering friend off it

A streamlined Arjuna bowls in the 1983 World Cup © Getty Images

On the eve of the World Cup final he told the many drooling media hounds that Shane Warne was just an average bowler. It caused a violent reaction, more so because "Chef" had been pecking away at the Aussie psyche for a few years and this was the ultimate insult. While Warne tightened with fury, Aravinda de Silva - Arjuna's right-hand man and master batsman - loosened up. Two buttons pressed, both for different purposes, both pushed to achieve one result.

Arjuna dabbed the winning run down to his favourite third-man area. Upon seeing it disappear to the boundary, he reached down and grabbed a stump. It was as if he were picking up the stake he had earlier rammed in the ground upon his arrival. That stake stood for a nation that had cracked the code to win a world title. Ranatunga's name was etched in history forever.

We became close companions off the field. He would take me home to dinner, offering his favourite foods and delights. Not surprisingly, he enjoyed a fine feast, probably more than he did cricket, and I loved hanging out with someone so at ease. He also helped me get expert treatment for my ailing legs, so I could get fit again after developing hamstring problems due to my knee condition. He took me to places I never knew existed, and I felt safer with him in a foreign land than I did in any other.

Arjuna wasn't really an arch-enemy or a player I loved to hate. I loved him, full stop. Mostly I loved the way he stood up to the big boys, the bullies, and bulldozed them back in his unique inspiring way. He represented the underdog.

Arjuna left everything out on the park and, going by his healthy waistline, that was quite a plateful.

MARTIN CROWE in Cricinfo MAY 2015

Truth be known, I love to hate the Australians more than anyone else. And therefore the man who got under their skin the most is my hero. Appearances can be deceiving, and when it comes to Arjuna Ranatunga, the rotund Sri Lankan mastermind, there was nothing soft in his underbelly. He is as tough a cricketer as I have ever come across.

We represented our countries at the same time, both very young, eager allrounders hoping to fit into the cut and thrust of international cricket. Sri Lanka were just beginning their climb, possessing many fine cricketers, if not hardened professionals. New Zealand were a nice mix of amateur and professional, led in example by the pro's pro, Richard Hadlee.

I first spoke to Arjuna while fielding under a helmet at short legin Kandy in 1984. He was defiantly chirpy at the crease, never taking a backward step. His game was a bit limited - the cut and sweep were his release shots. He appeared unfit, yet he never lacked for effort or punch. He quickly became known as "Chef": hungry, dressed in white, and ready to give hell to anyone who didn't conform to the rules of his workspace.

We teased each other a little but deep down we had huge respect for one another, and I loved his smile and zest for life. He had no out-of-control ego, or fear, just a massive heart and a cunning mind. Despite Sri Lanka having no experience as such, Arjuna soaked up all he could. It was as if it was preordained - his apprenticeship was a natural platform for him to learn how to mastermind his team to unprecedented glory.

He quickly became known as "Chef": hungry, dressed in white, and ready to give hell to anyone who didn't conform to the rules of his workspace

I was more comfortable bowling to Arjuna than batting against him. I could swing it away from him, and enjoyed following up my bouncers with a prolonged look to see his response. He was always muttering something and smiling. When he bowled to me, he knew I feared getting out to his miserable deflated wobblies.

Regrettably, he dismissed me too often, notably in Wellington, when I was one short of being the first Kiwi to post a triple-century. I recall the moment when he got to the end of his run-up, beaming ear to ear. He had a gift for me. At that precise moment, up popped the thought that I had already achieved the triple-century. I didn't remove the thought; instead, I hung on to the feeling a bit longer. "Heck, you've done it," I muttered.

Arjuna rolled in and offered up a juicy half-volley wide of off stump. It was a glorious finish to a hard-fought draw, and some history. I never saw the ball leave his hand. My mind was scrambled as I jumped from "Done it", to "Where is it?" Seeing it very late and very wide, I lashed out in desperation, the blade slicing the ball and sending a thick edge into the slip cordon. Hashan Tillakaratne, the wicketkeeper, moved swiftly and calmly to his right and plucked the ball millimetres from the ground.

While Arjuna was upset for me, I was angry and inconsolable. A couple of weeks later, in the Hamilton Test, he dealt it to me again with the same mode of dismissal. Unintentionally, he had got under my skin, in the nicest possible way. I began to hate facing his gentle floating autumn leaves.

By 1996 he was a wise sage. He knew his team and their strengths, and he knew what buttons needed pushing. He saw the Australians as an easy target. He saw how false they could be: loud, lippy banter masking their own fears, often turning into personal abuse when the pressure mounted. He believed the more they resorted to mental disintegration the more they exposed themselves, diverting their attention from their obvious skill and from the job at hand.

Truth be known, I love to hate the Australians more than anyone else. And therefore the man who got under their skin the most is my hero. Appearances can be deceiving, and when it comes to Arjuna Ranatunga, the rotund Sri Lankan mastermind, there was nothing soft in his underbelly. He is as tough a cricketer as I have ever come across.

We represented our countries at the same time, both very young, eager allrounders hoping to fit into the cut and thrust of international cricket. Sri Lanka were just beginning their climb, possessing many fine cricketers, if not hardened professionals. New Zealand were a nice mix of amateur and professional, led in example by the pro's pro, Richard Hadlee.

I first spoke to Arjuna while fielding under a helmet at short legin Kandy in 1984. He was defiantly chirpy at the crease, never taking a backward step. His game was a bit limited - the cut and sweep were his release shots. He appeared unfit, yet he never lacked for effort or punch. He quickly became known as "Chef": hungry, dressed in white, and ready to give hell to anyone who didn't conform to the rules of his workspace.

We teased each other a little but deep down we had huge respect for one another, and I loved his smile and zest for life. He had no out-of-control ego, or fear, just a massive heart and a cunning mind. Despite Sri Lanka having no experience as such, Arjuna soaked up all he could. It was as if it was preordained - his apprenticeship was a natural platform for him to learn how to mastermind his team to unprecedented glory.

He quickly became known as "Chef": hungry, dressed in white, and ready to give hell to anyone who didn't conform to the rules of his workspace

I was more comfortable bowling to Arjuna than batting against him. I could swing it away from him, and enjoyed following up my bouncers with a prolonged look to see his response. He was always muttering something and smiling. When he bowled to me, he knew I feared getting out to his miserable deflated wobblies.

Regrettably, he dismissed me too often, notably in Wellington, when I was one short of being the first Kiwi to post a triple-century. I recall the moment when he got to the end of his run-up, beaming ear to ear. He had a gift for me. At that precise moment, up popped the thought that I had already achieved the triple-century. I didn't remove the thought; instead, I hung on to the feeling a bit longer. "Heck, you've done it," I muttered.

Arjuna rolled in and offered up a juicy half-volley wide of off stump. It was a glorious finish to a hard-fought draw, and some history. I never saw the ball leave his hand. My mind was scrambled as I jumped from "Done it", to "Where is it?" Seeing it very late and very wide, I lashed out in desperation, the blade slicing the ball and sending a thick edge into the slip cordon. Hashan Tillakaratne, the wicketkeeper, moved swiftly and calmly to his right and plucked the ball millimetres from the ground.

While Arjuna was upset for me, I was angry and inconsolable. A couple of weeks later, in the Hamilton Test, he dealt it to me again with the same mode of dismissal. Unintentionally, he had got under my skin, in the nicest possible way. I began to hate facing his gentle floating autumn leaves.

By 1996 he was a wise sage. He knew his team and their strengths, and he knew what buttons needed pushing. He saw the Australians as an easy target. He saw how false they could be: loud, lippy banter masking their own fears, often turning into personal abuse when the pressure mounted. He believed the more they resorted to mental disintegration the more they exposed themselves, diverting their attention from their obvious skill and from the job at hand.

A streamlined Arjuna bowls in the 1983 World Cup © Getty Images

On the eve of the World Cup final he told the many drooling media hounds that Shane Warne was just an average bowler. It caused a violent reaction, more so because "Chef" had been pecking away at the Aussie psyche for a few years and this was the ultimate insult. While Warne tightened with fury, Aravinda de Silva - Arjuna's right-hand man and master batsman - loosened up. Two buttons pressed, both for different purposes, both pushed to achieve one result.

Arjuna dabbed the winning run down to his favourite third-man area. Upon seeing it disappear to the boundary, he reached down and grabbed a stump. It was as if he were picking up the stake he had earlier rammed in the ground upon his arrival. That stake stood for a nation that had cracked the code to win a world title. Ranatunga's name was etched in history forever.

We became close companions off the field. He would take me home to dinner, offering his favourite foods and delights. Not surprisingly, he enjoyed a fine feast, probably more than he did cricket, and I loved hanging out with someone so at ease. He also helped me get expert treatment for my ailing legs, so I could get fit again after developing hamstring problems due to my knee condition. He took me to places I never knew existed, and I felt safer with him in a foreign land than I did in any other.

Arjuna wasn't really an arch-enemy or a player I loved to hate. I loved him, full stop. Mostly I loved the way he stood up to the big boys, the bullies, and bulldozed them back in his unique inspiring way. He represented the underdog.

Arjuna left everything out on the park and, going by his healthy waistline, that was quite a plateful.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)