'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label xenophobia. Show all posts

Showing posts with label xenophobia. Show all posts

Friday, 16 February 2024

Sunday, 22 April 2018

Windrush saga exposes mixed feelings about immigrants like me

Abdulrazak Gurnah in The FT

In 1968, soon after arriving in England from Zanzibar as an 18-year-old student, I was talking with a friend while a radio played in the background. At some point we stopped talking and listened to a man speaking with tremulous passion about the dangers people like me represented for the future of Britain.

In 1968, soon after arriving in England from Zanzibar as an 18-year-old student, I was talking with a friend while a radio played in the background. At some point we stopped talking and listened to a man speaking with tremulous passion about the dangers people like me represented for the future of Britain.

It was Enoch Powell and we were listening to a clip of his “Rivers of Blood” speech. I knew little about British politics and did not know who Powell was. But in the days and weeks that followed, I heard him quoted at me by fellow students and bus conductors, and saw television footage of trade union marches in his support.

I have lived in Britain for most of the past 50 years and have watched, and participated in, the largely successful struggle to prevent Powell’s lurid prophecies about race war from coming true. But it would be foolish to imagine that all is set fair for the future of Britain and its migrant communities, because every few weeks we are provided with another example of the obstinate survival of antipathy and disregard. The treatment of the children of the “Windrush generation” who moved to the UK from the Caribbean several decades ago is the latest such episode.

The injustice is so staggering that Theresa May, the prime minister, and Amber Rudd, the home secretary, have been forced to apologise. But the consequences for Caribbean migrants who grew up in Britain of the “hostile environment” for illegal immigrants could hardly have been news to them.

In 2013, at the instigation of the Home Office, vans emblazoned with the message “Go home or face arrest” drove around parts of London with large immigrant populations. It may not have been intended that the clampdown on illegal immigration would snare such embarrassing prey as children of migrants who spent a lifetime working in the UK; but political expediency required that this small complication be ignored until it went away. That it has not is a result of the work of welfare, legal and political activists to make sure that the abuses against migrants and strangers are kept in plain sight.

Before the second world war, there was no law to restrict entry or residence in Britain for people who lived in her colonial territories. That is what it meant to be a global empire, and all the millions who were subjects of the British crown were free to come if they wished. There was no need to worry about controlling numbers because, if they became a problem, they were sent back, as happened after the race riots in various British port cities in 1919. In a rush of imperial hubris, the British Nationality Act was passed in 1948 to formalise the right of British colonial subjects to enter and live in the UK.

If the 1948 law was a desperate recruitment poster for cheap labour disguised as imperial largesse, the purpose of the successively meaner pieces of immigration legislation that began in 1962 was to slow and ultimately stop the arrival of dark-skinned former subjects of the British crown. It continued Britain’s centuries-long prevarication between sanctuary and xenophobia.

Why has the Windrush saga been so embarrassing for the government? The answer has to do with Britain’s fraught relationship with the Caribbean and a history of racial terror instigated and supervised for centuries by British money and power. Caribbean institutions are still largely modelled on British ones and, until recent disillusioning decades, the Caribbean sense of identity was linked with a connection to the British empire. It is remarkable that this should be so given the brutalities of the plantation economies that prevailed in the Caribbean territories. This is an ambivalence that Caribbean intellectuals have reflected on for more than a century. The most perfunctory browse through the writing of the region will provide examples of its intricate legacy.

What is now referred to as the Windrush generation was far from homogeneous. It included peasant workers, nurses, teachers, writers and artists. They came in response to the recruitment drive and because they were ambitious for a better life. They are in Britain for the same reasons that all migrants are here.

In time they brought their children, and those children grew up, were educated and worked all their lives in this country. As any stranger knows, particularly if he or she is black in Europe, it is vital to keep your paperwork in order. What recent events have shown is that not all the children of the Windrush generation did because they were confident that they were at home and had no need to prove their right to be here. It seems they reckoned without the ruthless politics of contemporary Britain, in which xenophobia and hatred do not repel, but instead win votes.

The Windrush saga has made headlines this week, but it has been going on for months — the bullying letters, the threatening sanctions against employers, the loss of employment, the withdrawal of benefits and healthcare, the detention and expulsion. Bullying in pursuit of bringing down the immigration numbers is never just or humane. But it is wrong to deny these people what are evidently their moral and legal rights. Their contribution to British society and culture has been immense.

When it became clear the law had caught the wrong people, someone should have called a halt instead of pressing on with the bullying. As Sentina Bristol, the mother of Dexter, a 57-year-old man born a British subject in Grenada who died after several months of going through this process, observed of the government in a recent interview: “They are intelligent people, they are people of power. We expect better from them.”

Saturday, 12 November 2016

We called it racism, now it’s nativism. The anti-migrant sentiment is just the same

Ian Jack in The Guardian

Nativism, according to the OED, is prejudice in favour of natives against strangers, which in present-day terms means a policy that will protect and promote the interests of indigenous or established inhabitants over those of immigrants. This usage has recently found favour among Brexiters anxious to distance themselves from accusations of racism and xenophobia. Officially, at least, it’s a bad thing. To Ukip’s only MP, Douglas Carswell, his party’s posters of queuing refugees represented nativism at its worst, and in his Clacton-on-Sea constituency he had them all taken down. To him, and others such as the MEP Daniel Hannan, Brexit has its foundations in the philosophies of Adam Smith and Edmund Burke, and absolutist beliefs in free trade and sovereignty: race and immigration have nothing to do with it.

Carswell appears a solitary and rather friendless figure: an officer who got into the wrong, rough-crewed lifeboat. But at least he’s probably sincere. Others use “nativism” to signify a more elevated approach to the immigrant/refugee question; it offers something more opaque and less cliched than a simple disavowal of racism. As the writer Jeremy Seabrook once noted, one effect of the 1965 Race Relations Act was to make people preface anything they might say about migrants with the words, “Well, of course, I’m no racialist”, before going on to provide “a sweeping and eloquent testimony to the contrary”. Half a century later, when immigrants are as likely to be white as black or brown, the sentence, “Well, of course, I’m no nativist”, may be emerging as that preface’s overdue replacement.

Seabrook’s observation appears in his 1971 book City Close-Up, composed mainly of interviews conducted in Blackburn, Lancashire, during the summer of 1969 and serialised on Radio 3 as a portrait of life in a fading industrial town, with its cobbled streets, derelict mills and ornate and oversized railway station. In Seabrook’s account, a tripe shop – “with its aspidistra and diploma to certify best-quality thick-seam tripe” – still stands open for custom, but elsewhere terraces of back-to-backs have been demolished to leave “fragments of crumbled brick and the smell of earth turned over for the first time in a century” while the willowherb spreads its fire over everything.

The book left an impression on me that has lasted 40-odd years. That was partly due to its accurate mention of the too-big station, where I’d once changed trains as a little boy and noticed through the crowd on the platform a glass case containing a splendid model of a two-funnel steamer, later identified as the boat that took you to the Isle of Man. What struck me most on first reading – and didn’t let me down on the second – was the frankness and intelligence with which the book recorded attitudes to immigration.

In 1969 the textile industry hadn’t quite died in Blackburn, which in Edwardian times had been the biggest cotton-weaving centre in the world. Imports of cotton goods to Britain began to exceed exports in 1958; the Blackburn industry employed two-thirds fewer people in the late 1960s than it had in the early 1950s. But more than 20 mills survived in the town, staffed largely by migrants from India and Pakistan whose willingness to work inconvenient shifts had prolonged the industry’s life and, in Seabrook’s words, relieved the indigenous working class of some of the least-desirable employment.

About 5,000 mainly Asian migrants then made up 5% of Blackburn’s population. Relations between established residents and newcomers weren’t easy. Seabrook noted that “an elaborate system of legends, myths and gossip” had evolved around the immigrants, “to legitimate a sustained and unflagging resentment of their presence, and of their allegedly harmful influence on the community”. One story told how a woman, thinking she’d heard rats scuttling overhead, opened her trapdoor one night to discover that the loft ran the whole length of the street, so as to be easily accessed via the end house where a Pakistani family lived. They had furnished this elongated attic with mattresses that could sleep 100 secret lodgers. In another story, a man known as “Packie Stan” slaughters goats and chickens in his backyard and depresses property prices wherever he goes.

Nativism, according to the OED, is prejudice in favour of natives against strangers, which in present-day terms means a policy that will protect and promote the interests of indigenous or established inhabitants over those of immigrants. This usage has recently found favour among Brexiters anxious to distance themselves from accusations of racism and xenophobia. Officially, at least, it’s a bad thing. To Ukip’s only MP, Douglas Carswell, his party’s posters of queuing refugees represented nativism at its worst, and in his Clacton-on-Sea constituency he had them all taken down. To him, and others such as the MEP Daniel Hannan, Brexit has its foundations in the philosophies of Adam Smith and Edmund Burke, and absolutist beliefs in free trade and sovereignty: race and immigration have nothing to do with it.

Carswell appears a solitary and rather friendless figure: an officer who got into the wrong, rough-crewed lifeboat. But at least he’s probably sincere. Others use “nativism” to signify a more elevated approach to the immigrant/refugee question; it offers something more opaque and less cliched than a simple disavowal of racism. As the writer Jeremy Seabrook once noted, one effect of the 1965 Race Relations Act was to make people preface anything they might say about migrants with the words, “Well, of course, I’m no racialist”, before going on to provide “a sweeping and eloquent testimony to the contrary”. Half a century later, when immigrants are as likely to be white as black or brown, the sentence, “Well, of course, I’m no nativist”, may be emerging as that preface’s overdue replacement.

Seabrook’s observation appears in his 1971 book City Close-Up, composed mainly of interviews conducted in Blackburn, Lancashire, during the summer of 1969 and serialised on Radio 3 as a portrait of life in a fading industrial town, with its cobbled streets, derelict mills and ornate and oversized railway station. In Seabrook’s account, a tripe shop – “with its aspidistra and diploma to certify best-quality thick-seam tripe” – still stands open for custom, but elsewhere terraces of back-to-backs have been demolished to leave “fragments of crumbled brick and the smell of earth turned over for the first time in a century” while the willowherb spreads its fire over everything.

The book left an impression on me that has lasted 40-odd years. That was partly due to its accurate mention of the too-big station, where I’d once changed trains as a little boy and noticed through the crowd on the platform a glass case containing a splendid model of a two-funnel steamer, later identified as the boat that took you to the Isle of Man. What struck me most on first reading – and didn’t let me down on the second – was the frankness and intelligence with which the book recorded attitudes to immigration.

In 1969 the textile industry hadn’t quite died in Blackburn, which in Edwardian times had been the biggest cotton-weaving centre in the world. Imports of cotton goods to Britain began to exceed exports in 1958; the Blackburn industry employed two-thirds fewer people in the late 1960s than it had in the early 1950s. But more than 20 mills survived in the town, staffed largely by migrants from India and Pakistan whose willingness to work inconvenient shifts had prolonged the industry’s life and, in Seabrook’s words, relieved the indigenous working class of some of the least-desirable employment.

About 5,000 mainly Asian migrants then made up 5% of Blackburn’s population. Relations between established residents and newcomers weren’t easy. Seabrook noted that “an elaborate system of legends, myths and gossip” had evolved around the immigrants, “to legitimate a sustained and unflagging resentment of their presence, and of their allegedly harmful influence on the community”. One story told how a woman, thinking she’d heard rats scuttling overhead, opened her trapdoor one night to discover that the loft ran the whole length of the street, so as to be easily accessed via the end house where a Pakistani family lived. They had furnished this elongated attic with mattresses that could sleep 100 secret lodgers. In another story, a man known as “Packie Stan” slaughters goats and chickens in his backyard and depresses property prices wherever he goes.

Often, Seabrook talked to people in groups. Many of the attitudes and complaints he records seem timeless. “I don’t believe all this bunkum that I’m being repeatedly told, that if you take all the immigrants out of the NHS, it would collapse,” says someone at a Labour party meeting. “Why are they allowed to get social security and child allowance and all the rest of it when they’ve never paid anything into our country?” asks a woman who, despite “20 years’ stamps”, says she can’t get a pension at 60. “I don’t approve of them coming to this country at all, unless they have special high qualifications,” says the wife of a businessman. “But I wouldn’t like it to be thought that it was because they were coloured. I wouldn’t mind if they’d conform to our way of life, but they don’t.”

Not everyone agrees. Not everyone has a view. Seabrook writes that Blackburn “is not a town full of racists, any more than it is a stronghold of liberal humanitarian values”, and that one strongly committed person in a group can influence the standpoint others will take. Some interviewees point out that immigrants work hard and Britain needs to take responsibility for the consequences of its empire. The dominant themes, however, are familiar: immigration needs controlling; migrants exploit the welfare system and put strains on housing and schools; and when in Rome they should do as the Romans do – “they should be more like us”.

In the front room of her terraced house, a Mrs Frost gathers some neighbours to meet Seabrook. It is as good a bit of writing on the subject as I have ever read. They talk angrily and emotionally about immigration until the paroxysm spends itself and “a certain uneasiness [comes over] the room, a sense of shame, the shame of people who have unburdened themselves to a stranger”.

Seabrook believes he has witnessed an expression of pain and powerlessness brought on by the “decay and dereliction” of their own lives and surroundings as much as by the unfamiliar dress, language and behaviour of their new neighbours. This feeling had found no outlet, politically or otherwise. All the writer can say is that it’s “something more complex and deep-rooted than what the metropolitan liberal evasively and easily dismisses as prejudice”.

Interestingly, Seabrook never felt he had to talk to the immigrants themselves. Talking to me this week, he said he was ashamed they felt marginal to his interest at the time, which was the fate of the English working class. In later books, the product of frequent visits to south Asia, he has completed a great historic and economic circle by describing the garment factories of Bangladesh. First, the cheap cotton spun and woven by Lancashire’s steam-powered mills wipes out the handloom cotton industry of Bengal. Second, less than two centuries later, the even cheaper cotton cloth made in the factories of Bengal and elsewhere in south and east Asia wipes out the steam-powered mills of Lancashire. Perhaps nowhere else offers such a symmetrical illustration of the way the world has changed.

Did any of us understand what we were caught up in? At the time it seemed something small and local that if ignored might go away. Seabrook remembers the late Barbara Castle, who was then Blackburn’s MP, warning him against writing about social discord and getting things “blown up out of proportion”. In the destruction of the world’s first industrial society, years before the rust belt began to rust, the foundations of the west’s recent troubles were laid.

Not everyone agrees. Not everyone has a view. Seabrook writes that Blackburn “is not a town full of racists, any more than it is a stronghold of liberal humanitarian values”, and that one strongly committed person in a group can influence the standpoint others will take. Some interviewees point out that immigrants work hard and Britain needs to take responsibility for the consequences of its empire. The dominant themes, however, are familiar: immigration needs controlling; migrants exploit the welfare system and put strains on housing and schools; and when in Rome they should do as the Romans do – “they should be more like us”.

In the front room of her terraced house, a Mrs Frost gathers some neighbours to meet Seabrook. It is as good a bit of writing on the subject as I have ever read. They talk angrily and emotionally about immigration until the paroxysm spends itself and “a certain uneasiness [comes over] the room, a sense of shame, the shame of people who have unburdened themselves to a stranger”.

Seabrook believes he has witnessed an expression of pain and powerlessness brought on by the “decay and dereliction” of their own lives and surroundings as much as by the unfamiliar dress, language and behaviour of their new neighbours. This feeling had found no outlet, politically or otherwise. All the writer can say is that it’s “something more complex and deep-rooted than what the metropolitan liberal evasively and easily dismisses as prejudice”.

Interestingly, Seabrook never felt he had to talk to the immigrants themselves. Talking to me this week, he said he was ashamed they felt marginal to his interest at the time, which was the fate of the English working class. In later books, the product of frequent visits to south Asia, he has completed a great historic and economic circle by describing the garment factories of Bangladesh. First, the cheap cotton spun and woven by Lancashire’s steam-powered mills wipes out the handloom cotton industry of Bengal. Second, less than two centuries later, the even cheaper cotton cloth made in the factories of Bengal and elsewhere in south and east Asia wipes out the steam-powered mills of Lancashire. Perhaps nowhere else offers such a symmetrical illustration of the way the world has changed.

Did any of us understand what we were caught up in? At the time it seemed something small and local that if ignored might go away. Seabrook remembers the late Barbara Castle, who was then Blackburn’s MP, warning him against writing about social discord and getting things “blown up out of proportion”. In the destruction of the world’s first industrial society, years before the rust belt began to rust, the foundations of the west’s recent troubles were laid.

Saturday, 25 June 2016

Brexit won’t shield Britain from the horror of a disintegrating EU

Yannis Varoufakis in The Guardian

Leave won because too many British voters identified the EU with authoritarianism, irrationality and contempt for parliamentary democracy while too few believed those of us who claimed that another EU was possible.

I campaigned for a radical remain vote reflecting the values of our pan-European Democracy in Europe Movement (DiEM25). I visited towns in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, seeking to convince progressives that dissolving the EU was not the solution. I argued that its disintegration would unleash deflationary forces of the type that predictably tighten the screws of austerity everywhere and end up favouring the establishment and its xenophobic sidekicks. Alongside John McDonnell, Caroline Lucas, Owen Jones, Paul Mason and others, I argued for a strategy of remaining in but against Europe’s established order and institutions.

‘The markets will soon settle down, and negotiations will probably lead to something like a Norwegian solution that allows the next British parliament to carve out a path toward some mutually agreed arrangement.’ Photograph: Leon Neal/AFP/Getty Images

The only man with a plan is Germany’s finance minister. Schäuble recognises in the post-Brexit fear his great opportunity to implement a permanent austerity union. Under his plan, eurozone states will be offered some carrots and a huge stick. The carrots will come in the form of a small eurozone budget to cover, in some part, unemployment benefits and bank deposit insurance. The stick will be a veto over national budgets.

If I am right, and Brexit leads to the construction of a permanent austerian iron cage for the remaining EU member states, there are two possible outcomes: One is that the cage will hold, in which case the institutionalised austerity will export deflation to Britain but also to China (whose further destabilisation will have secondary negative effects on Britain and the EU).

Another possibility is that the cage will be breached (by Italy or Finland leaving, for instance), the result being Germany’s own departure from the collapsing eurozone. But this will turn the new Deutschmark zone, which will probably end at the Ukrainian border, into a huge engine of deflation (as the new currency goes through the roof and German factories lose international markets). Britain and China had better brace themselves for an even greater deflation shock wave under this scenario.

The horror of these developments, from which Britain cannot be shielded by Brexit, is the main reason why I, and other members of DiEM25, tried to save the EU from the establishment that is driving Europeanism into the ground. I very much doubt that, despite their panic in Brexit’s aftermath, EU leaders will learn their lesson. They will continue to throttle voices calling for the EU’s democratisation and they will continue to rule through fear. Is it any wonder that many progressive Britons turned their back on this EU?

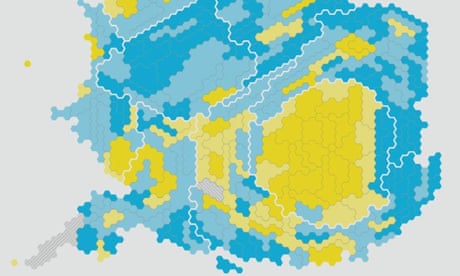

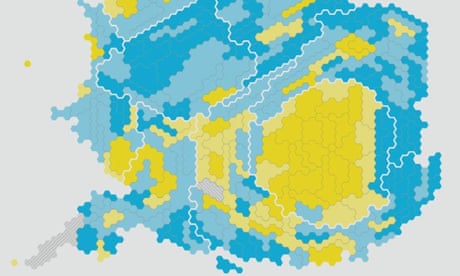

EU referendum full results – find out how your area voted

While I remain convinced that leave was the wrong choice, I welcome the British people’s determination to tackle the diminution of democratic sovereignty caused by the democratic deficit in the EU. And I refuse to be downcast, even though I count myself on the losing side of the referendum.

As of today, British and European democrats must seize on this vote to confront the establishment in London and Brussels more powerfully than before. The EU’s disintegration is now running at full speed. Building bridges across Europe, bringing democrats together across borders and political parties, is what Europe needs more than ever to avoid a slide into a xenophobic, deflationary, 1930s-like abyss.

Leave won because too many British voters identified the EU with authoritarianism, irrationality and contempt for parliamentary democracy while too few believed those of us who claimed that another EU was possible.

I campaigned for a radical remain vote reflecting the values of our pan-European Democracy in Europe Movement (DiEM25). I visited towns in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, seeking to convince progressives that dissolving the EU was not the solution. I argued that its disintegration would unleash deflationary forces of the type that predictably tighten the screws of austerity everywhere and end up favouring the establishment and its xenophobic sidekicks. Alongside John McDonnell, Caroline Lucas, Owen Jones, Paul Mason and others, I argued for a strategy of remaining in but against Europe’s established order and institutions.

Against us was an alliance of David Cameron (whose Brussels’ fudge reminded Britons of what they despise about the EU), the Treasury (and its ludicrous pseudo-econometric scare-mongering), the City (whose insufferable self-absorbed arrogance put millions of voters off the EU), Brussels (busily applying its latest treatment of fiscal waterboarding to the European periphery), Germany’s finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble (whose threats against British voters galvanised anti-German sentiment), France’s pitiable socialist government, Hillary Clinton and her merry Atlanticists (portraying the EU as part of another dangerous “coalition of the willing") and the Greek government (whose permanent surrender to punitive EU austerity made it so hard to convince the British working class that their rights were protected by Brussels).

The repercussions of the vote will be dire, albeit not the ones Cameron and Brussels had warned of. The markets will soon settle down, and negotiations will probably lead to something like a Norwegian solution that allows the next British parliament to carve out a path toward some mutually agreed arrangement. Schäuble and Brussels will huff and puff but they will, inevitably, seek such a settlement with London. The Tories will hang together, as they always do, guided by their powerful instinct of class interest. However, despite the relative tranquillity that will follow on from the current shock, insidious forces will be activated under the surface with a terrible capacity for inflicting damage on Europe and on Britain.

Italy, Finland, Spain, France, and certainly Greece, are unsustainable under the present arrangements. The architecture of the euro is a guarantee of stagnation and is deepening the debt-deflationary spiral that strengthens the xenophobic right. Populists in Italy and Finland, possibly in France, will demand referendums or other ways to disengage.

The repercussions of the vote will be dire, albeit not the ones Cameron and Brussels had warned of. The markets will soon settle down, and negotiations will probably lead to something like a Norwegian solution that allows the next British parliament to carve out a path toward some mutually agreed arrangement. Schäuble and Brussels will huff and puff but they will, inevitably, seek such a settlement with London. The Tories will hang together, as they always do, guided by their powerful instinct of class interest. However, despite the relative tranquillity that will follow on from the current shock, insidious forces will be activated under the surface with a terrible capacity for inflicting damage on Europe and on Britain.

Italy, Finland, Spain, France, and certainly Greece, are unsustainable under the present arrangements. The architecture of the euro is a guarantee of stagnation and is deepening the debt-deflationary spiral that strengthens the xenophobic right. Populists in Italy and Finland, possibly in France, will demand referendums or other ways to disengage.

‘The markets will soon settle down, and negotiations will probably lead to something like a Norwegian solution that allows the next British parliament to carve out a path toward some mutually agreed arrangement.’ Photograph: Leon Neal/AFP/Getty Images

The only man with a plan is Germany’s finance minister. Schäuble recognises in the post-Brexit fear his great opportunity to implement a permanent austerity union. Under his plan, eurozone states will be offered some carrots and a huge stick. The carrots will come in the form of a small eurozone budget to cover, in some part, unemployment benefits and bank deposit insurance. The stick will be a veto over national budgets.

If I am right, and Brexit leads to the construction of a permanent austerian iron cage for the remaining EU member states, there are two possible outcomes: One is that the cage will hold, in which case the institutionalised austerity will export deflation to Britain but also to China (whose further destabilisation will have secondary negative effects on Britain and the EU).

Another possibility is that the cage will be breached (by Italy or Finland leaving, for instance), the result being Germany’s own departure from the collapsing eurozone. But this will turn the new Deutschmark zone, which will probably end at the Ukrainian border, into a huge engine of deflation (as the new currency goes through the roof and German factories lose international markets). Britain and China had better brace themselves for an even greater deflation shock wave under this scenario.

The horror of these developments, from which Britain cannot be shielded by Brexit, is the main reason why I, and other members of DiEM25, tried to save the EU from the establishment that is driving Europeanism into the ground. I very much doubt that, despite their panic in Brexit’s aftermath, EU leaders will learn their lesson. They will continue to throttle voices calling for the EU’s democratisation and they will continue to rule through fear. Is it any wonder that many progressive Britons turned their back on this EU?

EU referendum full results – find out how your area voted

While I remain convinced that leave was the wrong choice, I welcome the British people’s determination to tackle the diminution of democratic sovereignty caused by the democratic deficit in the EU. And I refuse to be downcast, even though I count myself on the losing side of the referendum.

As of today, British and European democrats must seize on this vote to confront the establishment in London and Brussels more powerfully than before. The EU’s disintegration is now running at full speed. Building bridges across Europe, bringing democrats together across borders and political parties, is what Europe needs more than ever to avoid a slide into a xenophobic, deflationary, 1930s-like abyss.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)