'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Friday, 16 February 2024

Saturday, 10 September 2022

Thursday, 30 June 2022

Scientific Facts have a Half-Life - Life is Poker not Chess 4

Abridged and adapted from Thinking in Bets by Annie Duke

The Half-Life of Facts, by Samuel Arbesman, is a great read about how practically every fact we’ve ever known has been subject to revision or reversal. The book talks about the extinction of the coelacanth, a fish from the Late Cretaceous period. This was the period that also saw the extinction of dinosaurs and other species. In the late 1930s and independently in the mid 1950s, coelacanths were found alive and well. Arbesman quoted a list of 187 species of mammals declared extinct, more than a third of which have subsequently been discovered as un-extinct.

Given that even scientific facts have an expiration date, we would all be well advised to take a good hard look at our beliefs, which are formed and updated in a much more haphazard way than in science.

We would be better served as communicators and decision makers if we thought less about whether we are confident in our beliefs and more about how confident we are about each of our beliefs. What if, in addition to expressing what we believe, we also rated our level of confidence about the accuracy of our belief on a scale of zero to ten? Zero would mean we are certain a belief is not true. Ten would mean we are certain that our belief is true. Forcing ourselves to express how sure we are of our beliefs brings to plain sight the probabilistic nature of those beliefs, that we believe is almost never 100% or 0% accurate but, rather, somewhere in between.

Incorporating uncertainty in the way we think about what we believe creates open-mindedness, moving us closer to a more objective stance towards information that disagrees with us. We are less likely to succumb to motivated reasoning since it feels better to make small adjustments in degrees of certainty instead of having to grossly downgrade from ‘right’ to ‘’wrong’. This shifts us away from treating information that disagrees with us as a threat, as something we have to defend against, making us better able to truthseek.

There is no sin in finding out there is evidence that contradicts what we believe. The only sin is in not using that evidence as objectively as possible to refine that belief going forward. By saying, ‘I’m 80%’ and thereby communicating we aren’t sure, we open the door for others to tell us what they know. They realise they can contribute without having to confront us by saying or implying, ‘You’re wrong’. Admitting we are not sure is an invitation for help in refining our beliefs and that will make our beliefs more accurate over time as we are more likely to gather relevant information.

Acknowledging that decisions are bets based on our beliefs, getting comfortable with uncertainty and redefining right and wrong are integral to a good overall approach to decision making.

Wednesday, 29 June 2022

Being smart makes our bias worse: Life is Poker not Chess - 3

Abridged and adapted from Thinking in Bets by Annie Duke

We bet based on what we believe about the world.This is very good news: part of the skill in life comes from learning to be a better belief calibrator, using experience and information to more objectively update our beliefs to more accurately represent the world. The more accurate our beliefs, the better the foundation of the bets we make. However there is also some bad news: our beliefs can be way, way off.

Hearing is believing

We form beliefs in a haphazard way, believing all sorts of things based just on what we hear out in the world but haven’t researched for ourselves.

This is how we think we form abstract beliefs:

We hear something

We think about it and vet it, determining whether it is true or false; only after that

We form our belief

It turns out though, that we actually form abstract beliefs this way:

We hear something

We believe it to be true

Only sometimes, later, if we have the time or the inclination, we think about it and vet it, determining whether it is, in fact, true or false.

These belief formation methods had evolved due to a need for efficiency not accuracy. In fact, questioning what you see or hear could get you eaten in the jungle. However, assuming that you are no longer living in a jungle, we have failed to develop a high degree of scepticism to deal with materials available in the modern social media age. This general belief-formation process may affect our decision making in areas that can have significant consequences.

If we were good at updating our beliefs based on new information, our haphazard belief formation process might cause relatively few problems. Sadly, we form beliefs without vetting most of them, and maintain them even after receiving clear, corrective information.

Truthseeking, the desire to know the truth regardless of whether the truth aligns with the beliefs we currently hold, is not naturally supported by the way we process information. Instead of altering our beliefs to fit new information, we do the opposite, altering our interpretation of that information to fit our beliefs.

The stubbornness of beliefs

Once a belief is lodged, it becomes difficult to dislodge. It takes on a life of its own, leading us to notice and seek out evidence confirming our belief, rarely challenge the validity of confirming evidence, and ignore or work hard to actively discredit information contradicting the belief. This irrational, circular information processing pattern is called motivated reasoning.

Fake news works because people who already hold beliefs consistent with the story generally won’t question the evidence. Disinformation is even more powerful because the confirmable facts in the story make it feel like the information has been vetted, adding to the power of the narrative being pushed.

Fake news isn’t meant to change minds. The potency of fake news is that it entrenches beliefs its intended audience already has, and then amplifies them. The Internet is a playground for motivated reasoning. It provides the promise of access to a greater diversity of information sources and opinions than we’ve ever had available. Yet, we gravitate towards sources that confirm our beliefs. Every flavour is out there, but we tend to stick with our favourite.

Even when directly confronted with facts that disconfirm our beliefs, we don’t let facts get in the way.

Being smart makes it worse

Surprisingly, being smart can actually make bias worse. The smarter you are, the better you are at constructing a narrative that supports your beliefs, rationalising and framing the data to fit your argument or point of view.

Blind spot bias - is an irrationality where people are better at recognising biased reasoning in others but are blind to bias in themselves. It was found that blind spot bias is greater the smarter you are. Furthermore, people who were aware of their own biases were not better able to overcome them.

Dan Kahan discovered that the more numerate people made more mistakes interpreting data on emotionally charged topics than the less numerate subjects sharing the same beliefs. It turns out the better you are with numbers, the better you are at spinning those numbers to conform to and support your beliefs.

Wanna bet

Imagine taking part in a conversation with a friend about the movie Chintavishtayaya Shyamala. Best film of all time, introduces a bunch of new techniques by which directors could contribute to story-telling. ‘Obviously, it won the national award’ you gush, as part of a list of superlatives the film unquestionably deserves.

Then your friend says, ‘Wanna bet?’

Suddenly, you are not so sure. That challenge puts you on your heels, causing you to back off your declaration and question the belief that you just declared with such assurance.

Remember the order in which we form abstract beliefs:

We hear something

We believe it to be true

Only sometimes, later, if we have the time or the inclination, we think about it and vet it, determining whether it is, in fact, true or false.

‘Wanna bet?’ triggers us to engage in that third step that we only sometimes get to. Being asked if we're willing to bet money on it makes it much more likely that we will examine our information in a less biased way, be more honest with ourselves about how sure we are of our beliefs, and be more open to updating and calibrating our beliefs. The more objective we are, the more accurate our beliefs become. And the person who wins bets over the long run is the one with the more accurate beliefs.

Of course, in most instances, the person offering to bet isn’t actually looking to put any money on it. They are just making a point - a valid point that perhaps we overstated our conclusion or made our statement without including relevant caveats.

I’d imagine that if you went around challenging everyone with ‘Wanna bet?’ it would be difficult to make friends and you’d lose the ones you have. But that doesn’t mean we can’t change the framework for ourselves in the way we think about our biases. decisions and opinions.

Tuesday, 28 June 2022

Every Decision is a Bet : Life is poker not chess - 2

Abridged and adapted from Thinking in Bets by Annie Duke

Merriam Webster’s Online Dictionary defines ‘bet’ as ‘a choice made by thinking about what will probably happen’. ‘To risk losing (something) when you try to do or achieve something’ and ‘to make decisions that are based on the belief that something will happen or is true’.

These definitions often overlooked the border aspects of betting: choice, probability, risk, decision, belief. By this definition betting doesn’t have to take place only in a casino or against somebody else.

We routinely decide among alternatives, put resources at risk, assess the likelihood of different outcomes and consider what it is that we value. Every decision commits us to some course of action that, by definition, eliminates acting on other alternatives. All such decisions are bets. Not placing a bet on something is, itself a bet.

Choosing to go to the movies means that we are choosing to not do all other things with our time. If we accept a job offer, we are also choosing to foreclose all other alternatives. There is always an opportunity cost in choosing one path over others. This is betting in action.

The betting elements of decisions - choice, probability, risk etc. are more obvious in some situations than others. Investments are clearly bets. A decision about a stock (buy, don’t buy, sell, hold..) involves a choice about the best use of our financial resources.

We don’t think of our parenting choices as bets but they are. We want our children to be happy, productive adults when we send them out into the world. Whenever we make a parenting choice (about discipline, nutrition, parenting philosophy, where to live etc.), we are betting that our choice will achieve the future we want for our children.

Job and relocation decisions are bets. Sales negotiations and contracts are bets. Buying a house is a bet. Ordering the chicken instead of vegetables is a bet. Everything is a bet.

Most bets are bets against ourselves

In most of our decisions, we are not betting against another person. We are betting against all the future versions of ourselves that we are not choosing. Whenever we make a choice we are betting on a potential future. We are betting that the future version of us that results from the decisions we make will be better off. At stake in a decision is that the return to us (measured in money, time, happiness, health or whatever we value) will be greater than what we are giving up by betting against the other alternative future versions of us.

But, how can we be sure that we are choosing the alternative that is best for us? What if another alternative would bring us more happiness, satisfaction or money? The answer, of course, is we can’t be sure. Things outside our control (luck) can influence the result. The futures we imagine are merely possible. They haven’t happened yet. We can only make our best guess, given what we know and don’t know, at what the future will look like. When we decide, we are betting whatever we value on one set of possible and uncertain futures. That is where the risk is.

Poker players live in a world where that risk is made explicit. They can get comfortable with uncertainty because they put it up front in their decisions. Ignoring the risk and uncertainty in every decision might make us feel better in the short run, but the cost to the quality of our decision making can be immense. If we can find ways to be more comfortable with uncertainty, we can see the world more accurately and be better for it.

Monday, 27 June 2022

Don’t date anybody if you only want positive results! Life is poker not chess

Abridged and adapted from Thinking in Bets by Annie Duke

Suppose someone says, “I flipped a coin and it landed heads four times in a row. How likely is that to occur?”

It feels that should be a pretty easy question to answer. Once we do the maths on the probability of heads on four consecutive 50-50 flips, we can determine that would happen 6.25% of the time (0.5 x 0.5 x 0.5 x 0,.5).

The problem is that we came to this answer without knowing anything about the coin or the person flipping it. Is it a two-sided coin or three-sided or four? If it is two-sided, is it a two-headed coin? Even if the coin is two sided, is the coin weighted to land on heads more often than tails? Is the coin flipper a magician who is capable of influencing how the coin lands? This information is all incomplete, yet we answered the question as if we had examined the coin and knew everything about it.

Now if that person flipped the coin 10,000 times, giving us a sufficiently large sample size, we could figure out, with some certainty, whether the coin is fair. Four flips simply isn’t enough to determine much about the coin

We make this same mistake when we look for lessons in life’s results. Our lives are too short to collect enough data from our own experience to make it easy to dig down into decision quality from the small set of results we experience. If we buy a house, fix it up a little, and sell it three years later for 50% more than we paid. Does that mean we are smart at buying and selling property, or at fixing up houses? It could, but it could also mean there was a big upward trend in the market and buying almost any piece of property would have made just as much money. Bitcoin buyers may now wonder about the wisdom of their decisions.

The hazards of resulting

Take a moment to imagine your best decision or your worst decision. I’m willing to bet that your best decision preceded a good result and the worst decision preceded a bad result. This is a safe bet for me because we deduce an overly tight relationship between our decisions and the consequent results.

There is an imperfect relationship between results and decision quality. I never seem to come across anyone who identifies a bad decision when they got lucky with the result, or a well reasoned decision that didn’t work out. We are uncomfortable with the idea that luck plays a significant role in our lives. We assume causation when there is only a correlation and tend to cherry-pick data to confirm the narrative we prefer.

Poker and decisions

Poker is a game that mimics human decision making. Every poker hand requires making at least one decision (to fold or to stay) and some hands can require up to twenty decisions. During a poker game players get in about thirty hands per hour. This means a poker player makes hundreds of decisions at breakneck speed with every hand having immediate financial consequences.

It is a game of decision making with incomplete information. Valuable information remains hidden. There is also an element of luck in any outcome. You could make the best possible decision at every point and still lose the hand, because you don’t know what new cards will be dealt and revealed.

In addition, once the game is over, poker players must learn from that jumbled mass of decisions and outcomes, separating the luck from the skill, and guarding against using results to justify/criticise decisions made,

The quality of our lives is the sum of decision quality plus luck. Poker is a mirror to life and helps us recognise the mistakes we never spot because we win the hand anyway or the leeway to do everything right, still lose, and treat the losing result as proof that we made a mistake,

Decisions are bets on the future

Decisions aren’t ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ based on whether they turn out well on any particular iteration. An unwanted result doesn’t make our decision wrong if we had thought about the alternatives and probabilities in advance and made our decisions accordingly.

Our world is structured to give us lots of opportunities to feel bad about being wrong if we want to measure ourselves by outcomes. Don’t fall in love or even date anybody if you want only positive results.

Monday, 22 March 2021

Saturday, 30 January 2021

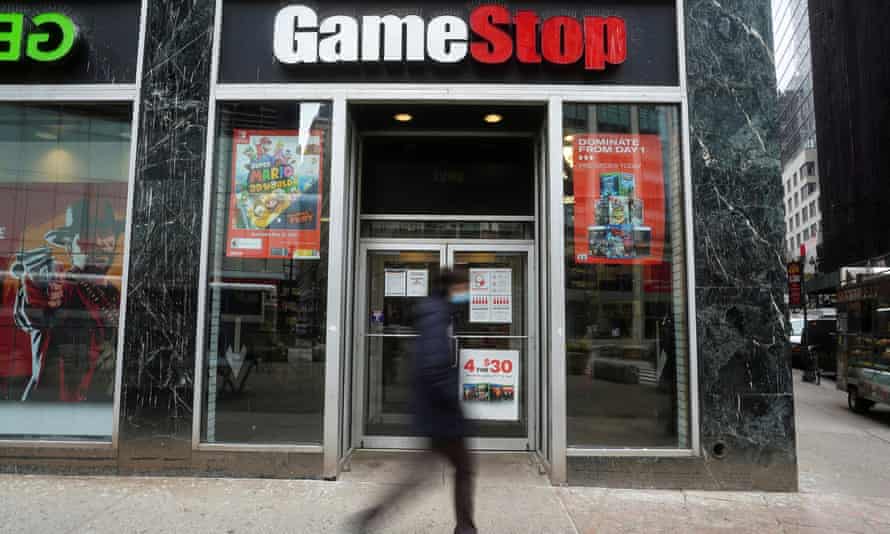

The GameStop affair is like tulip mania on steroids

Towards the end of 1636, there was an outbreak of bubonic plague in the Netherlands. The concept of a lockdown was not really established at the time, but merchant trade slowed to a trickle. Idle young men in the town of Haarlem gathered in taverns, and looked for amusement in one of the few commodities still trading – contracts for the delivery of flower bulbs the following spring. What ensued is often regarded as the first financial bubble in recorded history – the “tulip mania”.

Nearly 400 years later, something similar has happened in the US stock market. This week, the share price of a company called GameStop – an unexceptional retailer that appears to have been surprised and confused by the whole episode – became the battleground between some of the biggest names in finance and a few hundred bored (mostly) bros exchanging messages on the WallStreetBets forum, part of the sprawling discussion site Reddit.

The rubble is still bouncing in this particular episode, but the broad shape of what’s happened is not unfamiliar. Reasoning that a business model based on selling video game DVDs through shopping malls might not have very bright prospects, several of New York’s finest hedge funds bet against GameStop’s share price. The Reddit crowd appears to have decided that this was unfair and that they should fight back on behalf of gamers. They took the opposite side of the trade and pushed the price up, using derivatives and brokerage credit in surprisingly sophisticated ways to maximise their firepower.

To everyone’s surprise, the crowd won; the hedge funds’ risk management processes kicked in, and they were forced to buy back their negative positions, pushing the price even higher. But the stock exchanges have always frowned on this sort of concerted action, and on the use of leverage to manipulate the market. The sheer volume of orders had also grown well beyond the capacity of the small, fee-free brokerages favoured by the WallStreetBets crowd. Credit lines were pulled, accounts were frozen and the retail crowd were forced to sell; yesterday the price gave back a large proportion of its gains.

To people who know a lot about stock exchange regulation and securities settlement, this outcome was quite inevitable – it’s part of the reason why things like this don’t happen every day. To a lot of American Redditors, though, it was a surprising introduction to the complexity of financial markets, taking place in circumstances almost perfectly designed to convince them that the system is rigged for the benefit of big money.

Corners, bear raids and squeezes, in the industry jargon, have been around for as long as stock markets – in fact, as British hedge fund legend Paul Marshall points out in his book Ten and a Half Lessons From Experience something very similar happened last year at the start of the coronavirus lockdown, centred on a suddenly unemployed sports bookmaker called Dave Portnoy. But the GameStop affair exhibits some surprising new features.

Most importantly, it was a largely self-organising phenomenon. For most of stock market history, orchestrating a pool of people to manipulate markets has been something only the most skilful could achieve. Some of the finest buildings in New York were erected on the proceeds of this rare talent, before it was made illegal. The idea that such a pool could coalesce so quickly and without any obvious sign of a single controlling mind is brand new and ought to worry us a bit.

And although some of the claims made by contributors to WallStreetBets that they represent the masses aren’t very convincing – although small by hedge fund standards, many of them appear to have five-figure sums to invest – it’s unfamiliar to say the least to see a pool motivated by rage or other emotions as opposed to the straightforward desire to make money. Just as air traffic regulation is based on the assumption that the planes are trying not to crash into one another, financial regulation is based on the assumption that people are trying to make money for themselves, not to destroy it for other people.

When I think about market regulation, I’m always reminded of a saying of Édouard Herriot, the former mayor of Lyon. He said that local government was like an andouillette sausage; it had to stink a little bit of shit, but not too much. Financial markets aren’t video games, they aren’t democratic and small investors aren’t the backbone of capitalism. They’re nasty places with extremely complicated rules, which only work to the extent that the people involved in them trust one another. Speculation is genuinely necessary on a stock market – without it, you could be waiting days for someone to take up your offer when you wanted to buy or sell shares. But it’s a necessary evil, and it needs to be limited. It’s a shame that the Redditors found this out the hard way.

Sunday, 5 August 2018

Creating Routines for Self Improvement - Part 4 from Thinking in Bets

Wednesday, 25 July 2018

Thinking in Bets – Making smarter decisions when you don’t have all the facts – by Annie Duke

CHESS V POKER

- Chess, for all its strategic complexity, isn’t a great model for decision making in life, where most of our decisions involve hidden information and a much greater influence of luck.

- Poker, in contrast, is a game of incomplete information. It is a game of decision making under conditions of uncertainty over time. Valuable information remains hidden. There is always an element of luck in any outcome. You could make the best possible decision at every point and still lose the hand; because you don’t know what new cards will be dealt and revealed. Once the game is finished and you try to learn from the results, separating the quality of your decisions from the influence of luck is difficult.

- Incomplete information poses a challenge not just for split second decision making, but also for learning from past decisions. Imagine my difficulty in trying to figure out if I played my hand correctly when my opponents cards were never revealed for e.g. if the hand concluded after I made a bet and my opponents folded. All I know is that I won the chips. Did I play poorly and get lucky? Or did I play well?

- Life resembles poker, where all the uncertainty gives us the room to deceive ourselves and misinterpret the data.

- Poker gives us the leeway to make mistakes that we never spot because we win the hand anyway and so don’t go looking for them or

- The leeway to do everything right, still lose and treat the losing result as proof that we made a mistake.

REDEFINING Wrong

- When we think in advance about the chances of alternative outcomes and make a decision based on those chances, it doesn’t automatically make us wrong when things don’t work out. It just means that one event in a set of possible futures occurred.

BACKCASTING AND PRE MORTEM

- Backcasting means working backwards from a positive future.

- When it comes to thinking about the future – stand at the end (the outcome) and look backwards. This is more effective than looking forwards from the beginning.

- i.e. by working backwards from the goal, we plan our decision tree in more depth.

- We imagine we’ve already achieved a positive outcome, holding up a newspaper headline “We’ve Achieved our Goal” Then we think about how we got there.

- Identify the reasons they got there, what events occurred, what decisions were made, what went their way to get to the goal.

- It makes it possible to identify low probability events that must occur to reach the goal You then develop strategies to increase the chances of such events occurring or recognizing the goal is too ambitious.

- You can also develop responses to developments that interfere with reaching the goal and identify inflection points for re-evaluating the plan as the future unfolds.

- Pre mortem means working backwards from a negative future.

- Pre mortem is an investigation into something awful but before it happens.

- Imagine a headline “We failed to reach our Goals” challenges us to think about ways in which things could go wrong.

- People who imagine obstacles in the way of reaching their goals are more likely to achieve success (Research p223)

- A pre mortem helps us to anticipate potential obstacles.

- Come up with ways things can go wrong so that you can plan for them

- The exercise forces everyone to identify potential points of failure without fear of being viewed as a naysayer.

- Imagining both positive and negative futures helps us to build a realistic plan to achieve our goals.

Sunday, 25 September 2016

My difficult relationship with Wasim Akram

Scratch. Shake. Rub. Repeat.

His career is off to a flyer. The New South Welshman averages nearly 50. In 1995, openers don’t average anything near that much. For context, Mike Atherton only averages 38.

The Hobart pitch looks clean. Wasim has the ball. The recipe is complete.

New wicket, master tradesman and some chilly dense Hobart weather.

The cable knit sweaters are on. Even those with extra natural padding are wearing them.

Old timers predict that there will be some cut and swing. In their minds, it’s as certain as death and taxes. But it is likely to only last a few overs until the shine is gone from the ball. If Slater can connect with a cut shot or two, the danger will quickly subside.

Wasim has a lazy 12 step run up. Perhaps it is only 10? The left arm swings around like an angry propeller on a Spitfire. The ball pitches on a length, cuts in hard and strikes the pad.

Slater had no chance. His fidgeting hasn’t been demonstrative enough to wake up his feet. They didn’t move.

An appeal. A really good appeal. Not Out.

Hitting outside the line? Too high?

The replay indicates that many an umpire would have raised the finger.

The Pakistanis share a knowing wink. Darrell Hair looks concerned. He has just realised that this will be a tough morning for him.

Slater shakes it off. We expected this, right? It is not as though Wasim wastes too many new balls in these conditions.

Ball 2.

Same shape. Slightly quicker. Slightly shorter.

The 25-year-old Slater gets in behind it and scrubs a defensive prod to short cover.

It looked awkward.

Where feet were expected to move, they didn’t. Michael Slater often looked awkward.

Back in 1995, openers were expected to look in control. Stylish. Dapper. Like Fred Astaire dancing in the rain. Slater could be that guy, but it wasn’t his natural happy place. He was more Vanilla Ice. In your face. New, exciting and baggy clothes.

He just wanted to make runs. Quickly.

Ball 3.

The sucker ball.

Pushed across the right hander and holding its line. The keeper takes it in front of first slip. A nervous Slater doesn’t bite. He wanted to. It was his ball. That mad cut shot wanted to come out of its cage. It didn’t.

Maybe if it were Steve Harmison bowling and not Wasim Akram? Surely he would have pounced at it then?

Slater continues to fidget at the crease. Perhaps this is where Steve Smith learnt it from?

Ball 4.

A half volley outside off stump. Not super quick, but still sharp. The batsman strides out to meet it. Almost overstretching.

Then he defends.

Wasim has got inside his head. Why didn’t that ball swing? Why didn’t I give it hell? It was there to hit. I’ll get him next time.

Mark Taylor is at the other end. He is practising the flick off his pads. It would be a dangerous shot against Wasim. Across the line. An invitation to produce a leading edge.

Ball 5

It is a repeat of ball 2. This time Slater jumps a little as he plays it. But to be fair, he is well behind it. Surely he feels more comfortable now? Apart from the first ball, the others have offered little danger to a set batsman. Like jelly in a blast chiller, Slater sets at a rapid speed. But he is not set yet. However, he is close.

Ball 6

Like Slater, Wasim also sets quickly. This is his effort ball. A full in-swinging yorker. We’ve seen it before. Close your eyes and you can picture it. Mitchell Starc took this dream and copied it.

Slater gets hit on the toe. His bat is still on its journey towards the ball. His bat is too slow. Wasim is too fast.

Umpire Hair fires him.

Peak Wasim. Classic Wasim. Just Wasim.

A tease of what he could do. A sense of what he would do. Then he did it.

He is like a gift from the gods. What is not to love?

What is not to respect?

Fast forward five years.

The dark clouds of match fixing would soon fall over Pakistani cricket.

They were always threatening to come in from the north, as they circled above the Kyber Pass. Now they had arrived.

These clouds set a waypoint for Wasim Akram. They threatened to unleash a thunderstorm from hell.

Winds. Hail. Lightning.

Instead, when one looks up at them, they are full of potential menace, yet never quite create more than a minor inconvenience.

These clouds are known as the Qayyum Report.

The typed pages of investigation that are contained within it are Pakistan’s attempt to look into corruption within the national team.

It opens up like a well laid out crime novel. A slow and steady start. A scene being set. Some explosive twists. Inconclusive conclusions and a reader left wanting for more.

Justice Qayyum, the author, is also fallible as we discover later. A cricket lover. A man working essentially with many contradicting first hand accounts and hearsay. His heroes are under attack.

But one in particular gives him the most troublesome time.

Wasim.

The Qayyum Report is clear in its condemnation of Pakistan’s greatest ever swing bowler.

Ata-ur-Rehman swore on oath that he was offered 200,000 rupees by skipper Akram to perform poorly in an ODI against New Zealand in Christchurch in 93/94.

Aamir Sohail had, on oath, also spoken ill of Akram.

Akram then, using his own personal credit card, paid for Ata-ur-Rehman to fly to London. Here, Rehman visited Akram’s lawyer and signed an affidavit supporting Wasim against the existing one penned by Sohail.

Essentially, Akram paid for Rehman’s travel so that he could perjure himself.

Akram does not dispute that he paid for Rehman’s ticket.

Rehman originally alleged that Akram threatened to have him “fixed” if he didn’t follow orders. Rehman then retracted his story after Akram paid for that flight to London to visit his lawyer. Rehman decided that, in fact, Sohail had coerced him to speak against Akram.

Perjury. A broken witness.

However, the great Imran Khan also testified that Rehman had told him of Akram’s approaches.

It is recorded for all eternity in the Qayyum Report.

Imran doesn’t lie, does he? (Politicians don’t lie?)

Other allegations are made against Wasim Akram in the Qayyum report. However, they are the classic ‘he says / she says’-type argument. They focus on Akram feigning injury, bowling badly and manipulating batting orders so as to lose matches.

They are difficult to prove either way. There is little corroboration.

Justice Qayyum dismisses them.

However, back on the match fixing charge where there are elements of corroboration, Quyyam states the following:

“As regards to allegation one on its own, this commission is left with no option but to hold Wasim Akram not guilty of the charge of match-fixing. This the Commission does so only by giving Wasim Akram the benefit of the doubt.”

In isolation, natural justice clears Akram.

Not guilty.

We can all move on with our lives. Akram is still a national hero.

Or is he?

Qayyum goes on to say:

“However, once this commission looks at the allegations in their totality, this commission feels that all is not well here and that Wasim Akram is not above board. He has not co-operated with this Commission. It is only by giving Wasim Akram the benefit of the doubt after Ata-ur-Rehman changed his testimony in suspicious circumstances that he has not been found guilty of match-fixing. He cannot be said to be above suspicion.” [Emphasis added.]

So Akram is found not guilty because he helped finance a witness to change his story under oath?

What nonsense is this?

Think about it for just a second. Pause and reflect.

If this were a criminal trial, it wouldn’t be hard to argue that Akram tampered with a witness.

Unbelievable.

“It is, therefore, recommended that he be censured and be kept under strict vigilance and further probe be made either by the Government of Pakistan or by the Cricket Board into his assets acquired during his cricketing tenure and a comparison be made with his income. Furthermore, he should be fined Rs300,000.”

The classic Clayton’s verdict. You aren’t guilty, but please pay a fine for the little bit of guilt that you do harbour.

“More importantly, it is further recommended that Wasim Akram be removed from captaincy of the national team. The captain of the national team should have a spotless character and be above suspicion. Wasim Akram seems to be too sullied to hold that office.” [Emphasis added.]

Stained. But not guilty.

It is important to note that the Qayyum report was not a criminal trial. This impacts the burden of proof.

“.....it must be stated that the burden of proof is somewhere in between the criminal and normal civil standard.”

Akram argued that the burden of proof should be high. But of course, he would. The higher the burden of proof, the harder it is to convict him.

“It is not as high as the counsel for Wasim Akram recommended, that the case needs to be proven beyond a reasonable doubt.

This is a commission of inquiry and not a criminal court of trial so that standard need not be high.”

Its outputs are recommendations. Typically, outputs from these inquiries are followed by prosecutors and governments. As they should.

Pakistan moved on after this event. They purged themselves. Apparently, they chose to reject corruption in cricket.

Then Butt, Asif and Amir.

Then Amir back in the Pakistan national side after those with memories, including Misbah and Hafeez, initially protested.

Corruption - 1

Sanctity - 0

But the story takes another turn.

While all this is happening, Wasim Akram remained a powerful man. He took more power. His voice is now the most powerful in Pakistani cricket.

He becomes a commentator. He models. He tries coaching in the IPL and being an ambassador in the PSL.

He is Pakistan’s Mr Everywhere.

But if you don’t clean up filth properly, it festers and mould grows and eventually it rears its head once again.

Justice Qayyum later recalls that he had a “soft corner” for Wasim.

“He was a very great player, a very great bowler and I was his fan, and therefore that thing did weigh with me.”

Qayyum admits he was lenient to “one or two of them” based on reputation and skill.

Qayyum, like all men, is guilty of being fallible. But what a time to lose control to your weakness.

Can we deduce from this that without personal bias, Qayyum may have found Wasim guilty of match fixing?

For a swing bowler, Akram knew how to live right on the slippery edge of right and wrong.

He was almost a match fixer, but paid a fine for being one.

He coerced a witness to change his sworn testimony against him by using his own funds.

He was stripped of the captaincy.

All facts. Indisputable.

Yet, you all still adore him like a god.

You place his playing deeds ahead of the damage he did to the game.

Does being good at something absolve one from society’s judgement about what is right and wrong?

Should we allow that Akram is afforded a voice on our television screens, our newspapers, mingles with players and coaches professional teams?

Would you allow Chris Cairns to do it? He was found not guilty by a UK court of lying about match fixing.

Why is Wasim any different? Is it because Wasim was a better player than Cairns?

Then how about those actually found guilty of crimes against the sport of cricket?

Shane Warne is a convicted drug cheat and took money from bookies. Why do you cower to him?

Mark Waugh is an Australian selector. An official position. He also took money from bookies. Having said that, Cricket Australia has official bookmaker partners, so they aren’t even pretending to take this seriously.

I am not talking about those who get a speeding fine here.

I am talking about individuals who cheated the game. Put their selfishness ahead of the greater good. Frauds.

Why does the game owe these people anything?

Cricket is not society. It does not automatically have to bestow a second chance on anyone. Instead, it is the duty of everyone associated with the game to protect it.

Yet when it comes to our heroes, those who swung a ball in mysterious ways or batted like silk, we turn a blind eye.

Wasim is Wasim. He has made his choices. He has vandalised the sport. As has Warne. As has Mark Waugh.

Rod Marsh once placed a bet against a team he was playing in. Australia lost. Rod Marsh won big.

Rod Marsh is now the Chairman of Selectors for Cricket Australia.

If I were caught breaking serious rules at work, I would get fired. There is no way in hell that my employer would ever have me back.

In some industries, if I break the rules, I can never work in them again.

The legal profession. Working with children. Policing.

No second chances. Respect the fortunate position you have obtained or leave forever.

If cricket really wants to see corruption as a significant foe, why does it not take the same stance?

So next time you share a view with me about what Wasim has said, or what Warne did on the pitch, forgive me if I don’t partake in your idolisation.

For Wasim is not my idol and it is him who is to blame.

Thursday, 12 December 2013

Cricket and war - Champs today, chumps tomorrow

Alastair Cook's dismissal in Adelaide may well have been a statistical inevitability following a long sequence of (mostly successful) hook shots © PA Photos

| Moral courage is not revealed in the nature of mistakes but in their frequency - or, more accurately, in the case of good players, the infrequency of mistakes | |||

| |||