'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label software. Show all posts

Showing posts with label software. Show all posts

Wednesday, 17 July 2024

Monday, 12 June 2023

Monday, 22 March 2021

Sunday, 28 May 2017

When algorithms are racist

Ian Tucker in The Guardian

Joy Buolamwini is a graduate researcher at the MIT Media Lab and founder of the Algorithmic Justice League – an organisation that aims to challenge the biases in decision-making software. She grew up in Mississippi, gained a Rhodes scholarship, and she is also a Fulbright fellow, an Astronaut scholar and a Google Anita Borg scholar. Earlier this year she won a $50,000 scholarship funded by the makers of the film Hidden Figures for her work fighting coded discrimination.

A lot of your work concerns facial recognition technology. How did you become interested in that area?

When I was a computer science undergraduate I was working on social robotics – the robots use computer vision to detect the humans they socialise with. I discovered I had a hard time being detected by the robot compared to lighter-skinned people. At the time I thought this was a one-off thing and that people would fix this.

Later I was in Hong Kong for an entrepreneur event where I tried out another social robot and ran into similar problems. I asked about the code that they used and it turned out we’d used the same open-source code for face detection – this is where I started to get a sense that unconscious bias might feed into the technology that we create. But again I assumed people would fix this.

So I was very surprised to come to the Media Lab about half a decade later as a graduate student, and run into the same problem. I found wearing a white mask worked better than using my actual face.

This is when I thought, you’ve known about this for some time, maybe it’s time to speak up.

How does this problem come about?

Within the facial recognition community you have benchmark data sets which are meant to show the performance of various algorithms so you can compare them. There is an assumption that if you do well on the benchmarks then you’re doing well overall. But we haven’t questioned the representativeness of the benchmarks, so if we do well on that benchmark we give ourselves a false notion of progress.

When we look at it now it seems very obvious, but with work in a research lab, I understand you do the “down the hall test” – you’re putting this together quickly, you have a deadline, I can see why these skews have come about. Collecting data, particularly diverse data, is not an easy thing.

Joy Buolamwini is a graduate researcher at the MIT Media Lab and founder of the Algorithmic Justice League – an organisation that aims to challenge the biases in decision-making software. She grew up in Mississippi, gained a Rhodes scholarship, and she is also a Fulbright fellow, an Astronaut scholar and a Google Anita Borg scholar. Earlier this year she won a $50,000 scholarship funded by the makers of the film Hidden Figures for her work fighting coded discrimination.

A lot of your work concerns facial recognition technology. How did you become interested in that area?

When I was a computer science undergraduate I was working on social robotics – the robots use computer vision to detect the humans they socialise with. I discovered I had a hard time being detected by the robot compared to lighter-skinned people. At the time I thought this was a one-off thing and that people would fix this.

Later I was in Hong Kong for an entrepreneur event where I tried out another social robot and ran into similar problems. I asked about the code that they used and it turned out we’d used the same open-source code for face detection – this is where I started to get a sense that unconscious bias might feed into the technology that we create. But again I assumed people would fix this.

So I was very surprised to come to the Media Lab about half a decade later as a graduate student, and run into the same problem. I found wearing a white mask worked better than using my actual face.

This is when I thought, you’ve known about this for some time, maybe it’s time to speak up.

How does this problem come about?

Within the facial recognition community you have benchmark data sets which are meant to show the performance of various algorithms so you can compare them. There is an assumption that if you do well on the benchmarks then you’re doing well overall. But we haven’t questioned the representativeness of the benchmarks, so if we do well on that benchmark we give ourselves a false notion of progress.

When we look at it now it seems very obvious, but with work in a research lab, I understand you do the “down the hall test” – you’re putting this together quickly, you have a deadline, I can see why these skews have come about. Collecting data, particularly diverse data, is not an easy thing.

Outside of the lab, isn’t it difficult to tell that you’re discriminated against by an algorithm?

Absolutely, you don’t even know it’s an option. We’re trying to identify bias, to point out cases where bias can occur so people can know what to look out for, but also develop tools where the creators of systems can check for a bias in their design.

Instead of getting a system that works well for 98% of people in this data set, we want to know how well it works for different demographic groups. Let’s say you’re using systems that have been trained on lighter faces but the people most impacted by the use of this system have darker faces, is it fair to use that system on this specific population?

Georgetown Law recently found that one in two adults in the US has their face in the facial recognition network. That network can be searched using algorithms that haven’t been audited for accuracy. I view this as another red flag for why it matters that we highlight bias and provide tools to identify and mitigate it.

Besides facial recognition what areas have an algorithm problem?

The rise of automation and the increased reliance on algorithms for high-stakes decisions such as whether someone gets insurance of not, your likelihood to default on a loan or somebody’s risk of recidivism means this is something that needs to be addressed. Even admissions decisions are increasingly automated – what school our children go to and what opportunities they have. We don’t have to bring the structural inequalities of the past into the future we create, but that’s only going to happen if we are intentional.

If these systems are based on old data isn’t the danger that they simply preserve the status quo?

Absolutely. A study on Google found that ads for executive level positions were more likely to be shown to men than women – if you’re trying to determine who the ideal candidate is and all you have is historical data to go on, you’re going to present an ideal candidate which is based on the values of the past. Our past dwells within our algorithms. We know our past is unequal but to create a more equal future we have to look at the characteristics that we are optimising for. Who is represented? Who isn’t represented?

Isn’t there a counter-argument to transparency and openness for algorithms? One, that they are commercially sensitive and two, that once in the open they can be manipulated or gamed by hackers?

I definitely understand companies want to keep their algorithms proprietary because that gives them a competitive advantage, and depending on the types of decisions that are being made and the country they are operating in, that can be protected.

When you’re dealing with deep neural networks that are not necessarily transparent in the first place, another way of being accountable is being transparent about the outcomes and about the bias it has been tested for. Others have been working on black box testing for automated decision-making systems. You can keep your secret sauce secret, but we need to know, given these inputs, whether there is any bias across gender, ethnicity in the decisions being made.

Thinking about yourself – growing up in Mississippi, a Rhodes Scholar, a Fulbright Fellow and now at MIT – do you wonder that if those admissions decisions had been taken by algorithms you might not have ended up where you are?

If we’re thinking likely probabilities in the tech world, black women are in the 1%. But when I look at the opportunities I have had, I am a particular type of person who would do well. I come from a household where I have two college-educated parents – my grandfather was a professor in school of pharmacy in Ghana – so when you look at other people who have had the opportunity to become a Rhodes Scholar or do a Fulbright I very much fit those patterns. Yes, I’ve worked hard and I’ve had to overcome many obstacles but at the same time I’ve been positioned to do well by other metrics. So it depends on what you choose to focus on – looking from an identity perspective it’s as a very different story.

In the introduction to Hidden Figures the author Margot Lee Shetterly talks about how growing up near Nasa’s Langley Research Center in the 1960s led her to believe that it was standard for African Americans to be engineers, mathematicians and scientists…

That it becomes your norm. The movie reminded me of how important representation is. We have a very narrow vision of what technology can enable right now because we have very low participation. I’m excited to see what people create when it’s no longer just the domain of the tech elite, what happens when we open this up, that’s what I want to be part of enabling.

Absolutely, you don’t even know it’s an option. We’re trying to identify bias, to point out cases where bias can occur so people can know what to look out for, but also develop tools where the creators of systems can check for a bias in their design.

Instead of getting a system that works well for 98% of people in this data set, we want to know how well it works for different demographic groups. Let’s say you’re using systems that have been trained on lighter faces but the people most impacted by the use of this system have darker faces, is it fair to use that system on this specific population?

Georgetown Law recently found that one in two adults in the US has their face in the facial recognition network. That network can be searched using algorithms that haven’t been audited for accuracy. I view this as another red flag for why it matters that we highlight bias and provide tools to identify and mitigate it.

Besides facial recognition what areas have an algorithm problem?

The rise of automation and the increased reliance on algorithms for high-stakes decisions such as whether someone gets insurance of not, your likelihood to default on a loan or somebody’s risk of recidivism means this is something that needs to be addressed. Even admissions decisions are increasingly automated – what school our children go to and what opportunities they have. We don’t have to bring the structural inequalities of the past into the future we create, but that’s only going to happen if we are intentional.

If these systems are based on old data isn’t the danger that they simply preserve the status quo?

Absolutely. A study on Google found that ads for executive level positions were more likely to be shown to men than women – if you’re trying to determine who the ideal candidate is and all you have is historical data to go on, you’re going to present an ideal candidate which is based on the values of the past. Our past dwells within our algorithms. We know our past is unequal but to create a more equal future we have to look at the characteristics that we are optimising for. Who is represented? Who isn’t represented?

Isn’t there a counter-argument to transparency and openness for algorithms? One, that they are commercially sensitive and two, that once in the open they can be manipulated or gamed by hackers?

I definitely understand companies want to keep their algorithms proprietary because that gives them a competitive advantage, and depending on the types of decisions that are being made and the country they are operating in, that can be protected.

When you’re dealing with deep neural networks that are not necessarily transparent in the first place, another way of being accountable is being transparent about the outcomes and about the bias it has been tested for. Others have been working on black box testing for automated decision-making systems. You can keep your secret sauce secret, but we need to know, given these inputs, whether there is any bias across gender, ethnicity in the decisions being made.

Thinking about yourself – growing up in Mississippi, a Rhodes Scholar, a Fulbright Fellow and now at MIT – do you wonder that if those admissions decisions had been taken by algorithms you might not have ended up where you are?

If we’re thinking likely probabilities in the tech world, black women are in the 1%. But when I look at the opportunities I have had, I am a particular type of person who would do well. I come from a household where I have two college-educated parents – my grandfather was a professor in school of pharmacy in Ghana – so when you look at other people who have had the opportunity to become a Rhodes Scholar or do a Fulbright I very much fit those patterns. Yes, I’ve worked hard and I’ve had to overcome many obstacles but at the same time I’ve been positioned to do well by other metrics. So it depends on what you choose to focus on – looking from an identity perspective it’s as a very different story.

In the introduction to Hidden Figures the author Margot Lee Shetterly talks about how growing up near Nasa’s Langley Research Center in the 1960s led her to believe that it was standard for African Americans to be engineers, mathematicians and scientists…

That it becomes your norm. The movie reminded me of how important representation is. We have a very narrow vision of what technology can enable right now because we have very low participation. I’m excited to see what people create when it’s no longer just the domain of the tech elite, what happens when we open this up, that’s what I want to be part of enabling.

Monday, 10 June 2013

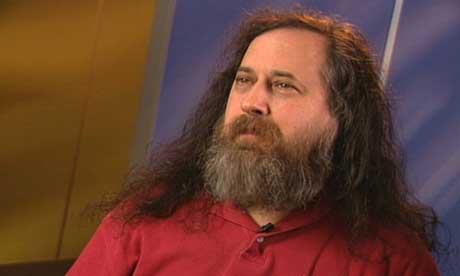

Cloud computing is a trap, warns GNU founder Richard Stallman

Web-based programs like Google's Gmail will force people to buy into locked, proprietary systems that will cost more and more over time, according to the free software campaigner

- Bobbie Johnson, technology correspondent

- guardian.co.uk,

Richard Stallman on cloud computing: "It's stupidity. It's worse than stupidity: it's a marketing hype campaign." Photograph: www.stallman.org

The concept of using web-based programs like Google's Gmail is "worse than stupidity", according to a leading advocate of free software.

Cloud computing – where IT power is delivered over the internet as you need it, rather than drawn from a desktop computer – has gained currency in recent years. Large internet and technology companies including Google, Microsoft and Amazon are pushing forward their plans to deliver information and software over the net.

But Richard Stallman, founder of the Free Software Foundation and creator of the computer operating system GNU, said that cloud computing was simply a trap aimed at forcing more people to buy into locked, proprietary systems that would cost them more and more over time.

"It's stupidity. It's worse than stupidity: it's a marketing hype campaign," he told The Guardian.

"Somebody is saying this is inevitable – and whenever you hear somebody saying that, it's very likely to be a set of businesses campaigning to make it true."

The 55-year-old New Yorker said that computer users should be keen to keep their information in their own hands, rather than hand it over to a third party.

His comments echo those made last week by Larry Ellison, the founder of Oracle, who criticised the rash of cloud computing announcements as "fashion-driven" and "complete gibberish".

"The interesting thing about cloud computing is that we've redefined cloud computing to include everything that we already do," he said. "The computer industry is the only industry that is more fashion-driven than women's fashion. Maybe I'm an idiot, but I have no idea what anyone is talking about. What is it? It's complete gibberish. It's insane. When is this idiocy going to stop?"

The growing number of people storing information on internet-accessible servers rather than on their own machines, has become a core part of the rise of Web 2.0 applications. Millions of people now upload personal data such as emails, photographs and, increasingly, their work, to sites owned by companies such as Google.

Computer manufacturer Dell recently even tried to trademark the term "cloud computing", although its application was refused.

But there has been growing concern that mainstream adoption of cloud computing could present a mixture of privacy and ownership issues, with users potentially being locked out of their own files.

Stallman, who is a staunch privacy advocate, advised users to stay local and stick with their own computers.

"One reason you should not use web applications to do your computing is that you lose control," he said. "It's just as bad as using a proprietary program. Do your own computing on your own computer with your copy of a freedom-respecting program. If you use a proprietary program or somebody else's web server, you're defenceless. You're putty in the hands of whoever developed that software."

Saturday, 6 April 2013

US universities offer software which they claim can instantly grade students' essays and short written answers

From The Independent 6/4/2013

Students could soon find their essays being instantly graded by a computer - rather than waiting weeks for a professor’s ponderous comments.

Students could soon find their essays being instantly graded by a computer - rather than waiting weeks for a professor’s ponderous comments.

New software developed in the United States which means they receive an instant grade through their computer if they send it online will be available for UK universities to use.

The software programme has been developed by EdX, a non-profit making enterprise set up by Harvard and Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and will be available free on the web to any organisation that wants to use it.

It uses artificial intelligence to grade students' essays and short written answers - freeing professors to carry out other work.

So far its use has been confined to the US - where a row is raging over whether it is right to use it to measure students’ essays which, in some subjects, include a fair amount of opinion around the factual content. Many academics believe it cannot replace the words of wisdom of a professional lecturer.

However, Anant Agarwal, president of EdX, predicted it would be a useful pedagogic tool - allowing students to redo essays over and over again thus improving the quality of their answers.

“There is huge value in learning with instant feedback,” he said. “Students are telling us they learn much better with instant feedback.”

He added: “We found that the quality of the grading is similar to the variation you find from instructor to instructor.”

An online petition against the practice, launched by a group calling itself Professionals Against Machine Scoring of Student Essays in High-Stakes Assessment, has amassed almost 2,000 signatures - including that of Noam Chomsky - protesting at the idea.

The group’s petition says: “Let’s face the realities of automatic essay scoring. Computers cannot ‘read’. They cannot measure the essentials of communication; accuracy, reasoning, adequacy of evidence, good sense, ethical stance, convincing argument, meaningful organisation, clarity and veracity, among others.”

On the other hand, students said that - if it was available for the individual to use - it could become a handy tool for a student to test the water on their essay before submitting to a professor for grading.

Sunday, 3 February 2013

Like poetry for software - Open Source

T+

Open source programme creators cater to the highest standards and give away their work for free, much like Ghalib who wrote not just for money but the discerning reader

Mirza Ghalib, the great poet of 19th century Delhi and one of the greatest poets in history, would have liked the idea of Open Source software. A couplet Mirza Ghalib wrote is indicative:

Bik jaate hain hum aap mata i sukhan ke saath

Lekin ayar i taba i kharidar dekh kar

(translated by Ralph Russell as:

I give my poetry away, and give myself along with it

But first I look for people who can value what I give).

Free versus proprietary

Ghalib’s sentiment of writing and giving away his verses reflects that of the Free and Open Source software (FOSS) movement, where thousands of programmers and volunteers write, edit, test and document software, which they then put out on the Internet for the whole world to use freely. FOSS software now dominates computing around the world. Most software now being used to run computing devices of different types — computers, servers, phones, chips in cameras or in cars, etc. — is either FOSS or created with FOSS. Software commonly sold in the market is referred to as proprietary software, in opposition to free and open source software, as it has restrictive licences that prohibit the user from seeing the source code and also distribute it freely. For instance, the Windows software sold by Microsoft corporation is proprietary in nature. The debate of FOSS versus proprietary software (dealing with issues such as which type is better, which is more secure, etc.) is by now quite old, and is not the argument of this article. What is important is that FOSS now constitutes a significant and dominant part of the entire software landscape.

The question many economists and others have pondered, and there are many special issues of academic journals dedicated to this question, is why software programmers and professionals, at the peak of their skills, write such high quality software and just give it away. They spend many hours working on very difficult and challenging problems, and when they find a solution, they eagerly distribute it freely over the Internet. Answers to why they do this range, broadly, in the vicinity of ascribing utility or material benefit that the programmers gain from this activity. Though these answers have been justified quite rigorously, they do not seem to address the core issue of free and open source software.

I find that the culture of poetry that thrived in the cultural renaissance of Delhi, at the time of Bahadur Shah Zafar, resembles the ethos of the open source movement and helps to answer why people write such excellent software, or poetry, and just give it away. Ghalib and his contemporaries strived to express sentiments, ideas and thoughts through perfect phrases. The placing of phrases and words within a couplet had to be exact, through a standard that was time-honoured and accepted. For example, the Urdu phrase ab thhe could express an entirely different meaning, when used in a context, from the phrase thhe ab, although, to an untrained ear they would appear the same. (Of course, poets in any era and writing in any language, also strove for the same perfection.)

Ghalib wrote his poetry for the discerning reader. His Persian poetry and prose is painstakingly created, has meticulous form and is written to the highest standards of those times. Though Ghalib did not have much respect for Urdu, the language of the population of Delhi, his Urdu ghazals too share the precision in language and form characteristic of his style. FOSS programmers also create software for the discerning user, of a very high quality, written in a style that caters to the highest standards of the profession. Since the source code of FOSS is readily available, unlike that for proprietary software, it is severely scrutinised by peers, and there is a redoubled effort on the part of the authors to create the highest quality.

Source material

Ghalib’s poetry, particularly his ghazals, have become the source materials for many others to base their own poetry. For example, Ghalib’s couplet Jii dhoondhta hai phir wohi ... (which is part of a ghazal) was adapted by Gulzar as Dil dhoondhta hai phir wohi..., with many additional couplets, as a beautiful song in the film Mausam. It was quite common in the days of the Emperor to announce azameen, a common metre and rhyming structure, that would then be used by many poets to compose their ghazals and orate them at a mushaira (public recitation of poetry). FOSS creators invariably extend and build upon FOSS that is already available. The legendary Richard Stallman, who founded the Free software movement, created a set of software tools and utilities that formed the basis of the revolution to follow. Millions of lines of code have been written based on this first set of free tools, they formed the zameen for what was to follow. Many programmers often fork a particular software, as Gulzar did with the couplet, and create new and innovative features. (Editor's note - Newton stated the same principle on his discoveries when he said, "If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants".)

Ghalib freely reviewed and critiqued poetry written by his friends and acquaintances. He sought review and criticism for his own work, although, it must be said, he granted few to be his equal in this art (much like the best FOSS programmers!). He was meticulous in providing reviews to his shagirds(apprentices) and tried to respond to them in two days, in which time he would carefully read everything and mark corrections on the paper. He sometimes complained about not having enough space on the page to mark his annotations. The FOSS software movement too has a strong culture of peer review and evaluation. Source code is reviewed and tested, and programmers make it a point to test and comment on code sent to them. Free software sites, such as Sourceforge.org, have elaborate mechanisms to help reviewers provide feedback, make bug reports and request features. The community thrives on timely and efficient reviews, and frequent releases of code.

Ghalib was an aristocrat who was brought up in the culture of poetry and music. He wrote poetry as it was his passion, and he wanted to create perfect form and structure, better than anyone had done before him. He did not directly write for money or compensation (and, in fact, spent most of his life rooting around for money, as he lived well beyond his means), but made it known to kings and nawabs that they could appoint him as a court poet with a generous stipend, and some did. In his later years, after the sacking of Delhi in 1857, he lamented that there was none left who could appreciate his work.

However, he was confident of his legacy, as he states in a couplet: “My poetry will win the world’s acclaim when I am gone.” FOSS creators too write for the passion and pleasure of writing great software and be acknowledged as great programmers, than for money alone. The lure of money cannot explain why an operating system like Linux, which would cost about $100 million to create if done by professional programmers, is created by hundreds of programmers around the world through thousands of hours of labour and kept out on the Internet for anyone to download and use for free. The urge to create such high quality software is derived from the passion to create perfect form and structure. A passion that Ghalib shared.

(Rahul De' is Hewlett-Packard Chair Professor of Information Systems at IIM, Bangalore)

Friday, 4 January 2013

How algorithms secretly shape the way we behave

Algorithms,

the key ingredients of all significant computer programs, have probably

influenced your Christmas shopping and may one day determine how you

vote

Program or be programmed? Schoolchildren learn to code. Photograph: Alamy

Keynes's observation (in his General Theory)

that "practical men who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any

intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct

economist" needs updating. Replace "economist" with "algorithm". And

delete "defunct", because the algorithms that now shape much of our

behaviour are anything but defunct. They have probably already

influenced your Christmas shopping, for example. They have certainly

determined how your pension fund is doing, and whether your application

for a mortgage has been successful. And one day they may effectively

determine how you vote.

On the face of it, algorithms – "step-by-step procedures for calculations" – seem unlikely candidates for the role of tyrant. Their power comes from the fact that they are the key ingredients of all significant computer programs and the logic embedded in them determines what those programs do. In that sense algorithms are the secret sauce of a computerised world.

And they are secret. Every so often, the veil is lifted when there's a scandal. Last August, for example, a "rogue algorithm" in the computers of a New York stockbroking firm, Knight Capital, embarked on 45 minutes of automated trading that eventually lost its owners $440m before it was stopped.

But, mostly, algorithms do their work quietly in the background. I've just logged on to Amazon to check out a new book on the subject – Automate This: How Algorithms Came to Rule Our World by Christopher Steiner. At the foot of the page Amazon tells me that two other books are "frequently bought together" with Steiner's volume: Nate Silver's The Signal and the Noise and Nassim Nicholas Taleb's Antifragile. This conjunction of interests is the product of an algorithm: no human effort was involved in deciding that someone who is interested in Steiner's book might also be interested in the writings of Silver and Taleb.

But book recommendations are relatively small beer – though I suspect they will have influenced a lot of online shopping at this time of year, as people desperately seek ideas for presents. The most powerful algorithm in the world is PageRank – the one that Google uses to determine the rankings of results from web searches – for the simple reason that, if your site doesn't appear in the first page of results, then effectively it doesn't exist. Not surprisingly, there is a perpetual arms race (euphemistically called search engine optimisation) between Google and people attempting to game PageRank. Periodically, Google tweaks the algorithm and unleashes a wave of nasty surprises across the web as people find that their hitherto modestly successful online niche businesses have suddenly – and unaccountably – disappeared.

PageRank thus gives Google awesome power. And, ever since Lord Acton's time, we know what power does to people – and institutions. So the power of PageRank poses serious regulatory issues for governments. On the one hand, the algorithm is a closely guarded commercial secret – for obvious reasons: if it weren't, then the search engine optimisers would have a field day and all search results would be suspect. On the other hand, because it's secret, we can't be sure that Google isn't skewing results to favour its own commercial interests, as some people allege.

Besides, there's more to power than commercial clout. Many years ago, the sociologist Steven Lukes pointed out that power comes in three varieties: the ability to stop people doing what they want to do; the ability to compel them to do things that they don't want to do: and the ability to shape the way they think. This last is the power that mass media have, which is why the Leveson inquiry was so important.

But, in a way, algorithms also have that power. Take, for example, the one that drives Google News. This was recently subjected to an illuminating analysis by Nick Diakopoulos from the Nieman Journalism Lab. Google claims that its selection of noteworthy news stories is "generated entirely by computer algorithms without human editors. No humans were harmed or even used in the creation of this page."

The implication is that the selection process is somehow more "objective" than a human-mediated one. Diakopoulos takes this cosy assumption apart by examining the way the algorithm works. There's nothing sinister about it, but it highlights the importance of understanding how software works. The choice that faces citizens in a networked world is thus: program or be programmed.

On the face of it, algorithms – "step-by-step procedures for calculations" – seem unlikely candidates for the role of tyrant. Their power comes from the fact that they are the key ingredients of all significant computer programs and the logic embedded in them determines what those programs do. In that sense algorithms are the secret sauce of a computerised world.

And they are secret. Every so often, the veil is lifted when there's a scandal. Last August, for example, a "rogue algorithm" in the computers of a New York stockbroking firm, Knight Capital, embarked on 45 minutes of automated trading that eventually lost its owners $440m before it was stopped.

But, mostly, algorithms do their work quietly in the background. I've just logged on to Amazon to check out a new book on the subject – Automate This: How Algorithms Came to Rule Our World by Christopher Steiner. At the foot of the page Amazon tells me that two other books are "frequently bought together" with Steiner's volume: Nate Silver's The Signal and the Noise and Nassim Nicholas Taleb's Antifragile. This conjunction of interests is the product of an algorithm: no human effort was involved in deciding that someone who is interested in Steiner's book might also be interested in the writings of Silver and Taleb.

But book recommendations are relatively small beer – though I suspect they will have influenced a lot of online shopping at this time of year, as people desperately seek ideas for presents. The most powerful algorithm in the world is PageRank – the one that Google uses to determine the rankings of results from web searches – for the simple reason that, if your site doesn't appear in the first page of results, then effectively it doesn't exist. Not surprisingly, there is a perpetual arms race (euphemistically called search engine optimisation) between Google and people attempting to game PageRank. Periodically, Google tweaks the algorithm and unleashes a wave of nasty surprises across the web as people find that their hitherto modestly successful online niche businesses have suddenly – and unaccountably – disappeared.

PageRank thus gives Google awesome power. And, ever since Lord Acton's time, we know what power does to people – and institutions. So the power of PageRank poses serious regulatory issues for governments. On the one hand, the algorithm is a closely guarded commercial secret – for obvious reasons: if it weren't, then the search engine optimisers would have a field day and all search results would be suspect. On the other hand, because it's secret, we can't be sure that Google isn't skewing results to favour its own commercial interests, as some people allege.

Besides, there's more to power than commercial clout. Many years ago, the sociologist Steven Lukes pointed out that power comes in three varieties: the ability to stop people doing what they want to do; the ability to compel them to do things that they don't want to do: and the ability to shape the way they think. This last is the power that mass media have, which is why the Leveson inquiry was so important.

But, in a way, algorithms also have that power. Take, for example, the one that drives Google News. This was recently subjected to an illuminating analysis by Nick Diakopoulos from the Nieman Journalism Lab. Google claims that its selection of noteworthy news stories is "generated entirely by computer algorithms without human editors. No humans were harmed or even used in the creation of this page."

The implication is that the selection process is somehow more "objective" than a human-mediated one. Diakopoulos takes this cosy assumption apart by examining the way the algorithm works. There's nothing sinister about it, but it highlights the importance of understanding how software works. The choice that faces citizens in a networked world is thus: program or be programmed.

Wednesday, 21 March 2012

Insider trading 9/11 ... the facts laid bare

AN ASIA TIMES

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE INVESTIGATION

By Lars Schall

Is there any truth in the allegations that informed circles made substantial profits in the financial markets in connection to the terror attacks of September 11, 2001, on the United States?

Arguably, the best place to start is by examining put options, which occurred around Tuesday, September 11, 2001, to an abnormal extent, and at the beginning via software that played a key role: the Prosecutor's Management Information System, abbreviated as PROMIS. [i]

PROMIS is a software program that seems to be fitted with almost "magical" abilities. Furthermore, it is the subject of a decades-long dispute between its inventor, Bill Hamilton, and various people/institutions associated with intelligence agencies, military and security consultancy firms. [1]

One of the "magical" capabilities of PROMIS, one has to assume, is that it is equipped with artificial intelligence and was apparently from the outset “able to simultaneously read and integrate any number of different computer programs or databases, regardless of the language in which the original programs had been written or the operating systems and platforms on which that database was then currently installed." [2]

And then it becomes really interesting:

This seems all the more urgent if you add to the PROMIS capabilities "that it was a given that PROMIS was used for a wide variety of purposes by intelligence agencies, including the real-time monitoring of stock transactions on all the world´s major financial markets". [4]

We are therefore dealing with a software that

a) Infiltrates computer and communication systems without being noticed.

b) Can manipulate data.

c) Is capable to track the global stock market trade in real time.

Point c is relevant to all that happened in connection with the never completely cleared up transactions that occurred just before September 11, [5] and of which the former chairman of the Deutsche Bundesbank Ernst Weltke said "could not have been planned and carried out without a certain knowledge". [6]

I specifically asked financial journalist Max Keiser, who for years had worked on Wall Street as a stock and options trader, about the put option trades. Keiser pointed out in this context that he "had spoken with many brokers in the towers of the World Trade Center around that time. I heard firsthand about the airline put trade from brokers at Cantor Fitzgerald days before." He then talked with me about an explosive issue, on which Ruppert elaborated in detail in Crossing the Rubicon.

On September 12, the chairman of the board of Deutsche Bank Alex Brown, Mayo A Shattuck III, suddenly and quietly renounced his post, although he still had a three-year contract with an annual salary of several million US dollars. One could perceive that as somehow strange.

A few weeks later, the press spokesperson of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) at that time, Tom Crispell, declined all comments, when he was contacted for a report for Ruppert´s website From the Wilderness, and had being asked "whether the Treasury Department or FBI [Federal Bureau of Investigation] had questioned CIA executive director and former Deutsche Bank-Alex Brown CEO [chief executive officer], A B 'Buzzy' Krongard, about CIA monitoring of financial markets using PROMIS and his former position as overseer of Brown's 'private client' relations." [8]

Just before he was recruited personally by former CIA chief George Tenet for the CIA, Krongard supervised mainly private client banking at Alex Brown. [9]

In any case, after 9/11 on the first trading day, when the US stock markets were open again, the stock price of UAL declined by 43%. (The four aircraft hijacked on September 11 were American Airlines Flight 11, American Airlines Flight 77 and UAL flights 175 and 93.)

With his background as a former options trader, Keiser explained an important issue to me in that regard.

Open interest describes contracts which have not been settled (been exercised) by the end of the trading session, but are still open. Not hedged in the stock market means that the buyer of a (put or call) option holds no shares of the underlying asset, by which he might be able to mitigate or compensate losses if his trade doesn't work out, or phrased differently: one does not hedge, because it is unnecessary, since one knows that the bet is one, pardon, "dead sure thing." (In this respect it is thus not really a bet, because the result is not uncertain, but a foregone conclusion.)

In this case, the vehicle of the calculation was "ridiculously cheap put options which give the holder the ‘right' for a period of time to sell certain shares at a price which is far below the current market price - which is a highly risky bet, because you lose money if at maturity the market price is still higher than the price agreed in the option. However, when these shares fell much deeper after the terrorist attacks, these options multiplied their value several hundred times because by now the selling price specified in the option was much higher than the market price. These risky games with short options are a sure indication for investors who knew that within a few days something would happen that would drastically reduce the market price of those shares." [11]

Software such as PROMIS in turn is used with the precise intent to monitor the stock markets in real time to track price movements that appear suspicious. Therefore, the US intelligence services must have received clear warnings from the singular, never before sighted transactions prior to 9/11.

Of great importance with regard to the track, which should lead to the perpetrators if you were seriously contemplating to go after them, is this:

In addition, there are also ways and means for insiders to veil their tracks. In order to be less obvious, "the insiders could trade small numbers of contracts. These could be traded under multiple accounts to avoid drawing attention to large trading volumes going through one single large account. They could also trade small volumes in each contract but trade more contracts to avoid drawing attention. As open interest increases, non-insiders may detect a perceived signal and increase their trading activity. Insiders can then come back to enter into more transactions based on a seemingly significant trade signal from the market. In this regard, it would be difficult for the CBOE to ferret out the insiders from the non-insiders, because both are trading heavily." [13]

The matter which needs clarification here is generally judged by Keiser as follows:

So far, so good. In the same month, however, the San Francisco Chronicle newspaper reported that the SEC took the unprecedented step to deputize hundreds, if not even thousands of key stakeholders in the private sector for their investigation. In a statement that was sent to almost all listed companies in the US, the SEC asked the addressed companies to assign senior staff for the investigation, who would be aware of "the sensitive nature" of the case and could be relied on to "exercise appropriate discretion". [15]

In essence, it was about controlling information, not about provision and disclosure of facts. Such a course of action involves compromising consequences. Ruppert:

By Lars Schall

Is there any truth in the allegations that informed circles made substantial profits in the financial markets in connection to the terror attacks of September 11, 2001, on the United States?

Arguably, the best place to start is by examining put options, which occurred around Tuesday, September 11, 2001, to an abnormal extent, and at the beginning via software that played a key role: the Prosecutor's Management Information System, abbreviated as PROMIS. [i]

PROMIS is a software program that seems to be fitted with almost "magical" abilities. Furthermore, it is the subject of a decades-long dispute between its inventor, Bill Hamilton, and various people/institutions associated with intelligence agencies, military and security consultancy firms. [1]

One of the "magical" capabilities of PROMIS, one has to assume, is that it is equipped with artificial intelligence and was apparently from the outset “able to simultaneously read and integrate any number of different computer programs or databases, regardless of the language in which the original programs had been written or the operating systems and platforms on which that database was then currently installed." [2]

And then it becomes really interesting:

What would you do if you possessed software that could think, understand every major language in the world, that provided peep-holes into everyone else’s computer "dressing rooms", that could insert data into computers without people’s knowledge, that could fill in blanks beyond human reasoning, and also predict what people do - before they did it? You would probably use it, wouldn't you? [3]Granted, these capabilities sound hardly believable. In fact, the whole story of PROMIS, which Mike Ruppert develops in the course of his book Crossing the Rubicon in all its bizarre facets and turns, seems as if someone had developed a novel in the style of Philip K Dick and William Gibson. However, what Ruppert has collected about PROMIS is based on reputable sources as well as on results of personal investigations, which await a jury to take a first critical look at.

This seems all the more urgent if you add to the PROMIS capabilities "that it was a given that PROMIS was used for a wide variety of purposes by intelligence agencies, including the real-time monitoring of stock transactions on all the world´s major financial markets". [4]

We are therefore dealing with a software that

a) Infiltrates computer and communication systems without being noticed.

b) Can manipulate data.

c) Is capable to track the global stock market trade in real time.

Point c is relevant to all that happened in connection with the never completely cleared up transactions that occurred just before September 11, [5] and of which the former chairman of the Deutsche Bundesbank Ernst Weltke said "could not have been planned and carried out without a certain knowledge". [6]

I specifically asked financial journalist Max Keiser, who for years had worked on Wall Street as a stock and options trader, about the put option trades. Keiser pointed out in this context that he "had spoken with many brokers in the towers of the World Trade Center around that time. I heard firsthand about the airline put trade from brokers at Cantor Fitzgerald days before." He then talked with me about an explosive issue, on which Ruppert elaborated in detail in Crossing the Rubicon.

Max Keiser: There are many aspects concerning these option purchases that have not been disclosed yet. I also worked at Alex Brown & Sons (ABS). Deutsche Bank bought Alex Brown & Sons in 1999. When the attacks occurred, ABS was owned by Deutsche Bank. An important person at ABS was Buzzy Krongard. I have met him several times at the offices in Baltimore. Krongard had transferred to become executive director at the CIA. The option purchases, in which ABS was involved, occurred in the offices of ABS in Baltimore. The noise which occurred between Baltimore, New York City and Langley was interesting, as you can imagine, to say the least.Under consideration here is the fact that Alex Brown, a subsidiary of Deutsche Bank (where many of the alleged 9/11 hijackers handled their banking transactions - for example Mohammed Atta) traded massive put options purchases on United Airlines Company UAL through the Chicago Board Option Exchange (CBOE) - "to the embarrassment of investigators", as British newspaper The Independent reported. [7]

On September 12, the chairman of the board of Deutsche Bank Alex Brown, Mayo A Shattuck III, suddenly and quietly renounced his post, although he still had a three-year contract with an annual salary of several million US dollars. One could perceive that as somehow strange.

A few weeks later, the press spokesperson of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) at that time, Tom Crispell, declined all comments, when he was contacted for a report for Ruppert´s website From the Wilderness, and had being asked "whether the Treasury Department or FBI [Federal Bureau of Investigation] had questioned CIA executive director and former Deutsche Bank-Alex Brown CEO [chief executive officer], A B 'Buzzy' Krongard, about CIA monitoring of financial markets using PROMIS and his former position as overseer of Brown's 'private client' relations." [8]

Just before he was recruited personally by former CIA chief George Tenet for the CIA, Krongard supervised mainly private client banking at Alex Brown. [9]

In any case, after 9/11 on the first trading day, when the US stock markets were open again, the stock price of UAL declined by 43%. (The four aircraft hijacked on September 11 were American Airlines Flight 11, American Airlines Flight 77 and UAL flights 175 and 93.)

With his background as a former options trader, Keiser explained an important issue to me in that regard.

Max Keiser: Put options are, if they are employed in a speculative trade, basically bets that stock prices will drop abruptly. The purchaser, who enters a time-specific contract with a seller, does not have to own the stock at the time when the contract is purchased.Related to the issue of insider trading via (put or call) options there is also a noteworthy definition by the Swiss economists Remo Crameri, Marc Chesney and Loriano Mancini, notably that an option trade may be "identified as informed" - but is not yet (legally) proven - "when it is characterized by an unusual large increment in open interest and volume, induces large gains, and is not hedged in the stock market". [10]

Open interest describes contracts which have not been settled (been exercised) by the end of the trading session, but are still open. Not hedged in the stock market means that the buyer of a (put or call) option holds no shares of the underlying asset, by which he might be able to mitigate or compensate losses if his trade doesn't work out, or phrased differently: one does not hedge, because it is unnecessary, since one knows that the bet is one, pardon, "dead sure thing." (In this respect it is thus not really a bet, because the result is not uncertain, but a foregone conclusion.)

In this case, the vehicle of the calculation was "ridiculously cheap put options which give the holder the ‘right' for a period of time to sell certain shares at a price which is far below the current market price - which is a highly risky bet, because you lose money if at maturity the market price is still higher than the price agreed in the option. However, when these shares fell much deeper after the terrorist attacks, these options multiplied their value several hundred times because by now the selling price specified in the option was much higher than the market price. These risky games with short options are a sure indication for investors who knew that within a few days something would happen that would drastically reduce the market price of those shares." [11]

Software such as PROMIS in turn is used with the precise intent to monitor the stock markets in real time to track price movements that appear suspicious. Therefore, the US intelligence services must have received clear warnings from the singular, never before sighted transactions prior to 9/11.

Of great importance with regard to the track, which should lead to the perpetrators if you were seriously contemplating to go after them, is this:

Max Keiser: The Options Clearing Corporation has a duty to handle the transactions, and does so rather anonymously - whereas the bank that executes the transaction as a broker can determine the identity of both parties.But that may have hardly ever been the intention of the regulatory authorities when the track led to, amongst others, Alvin Bernard "Buzzy" Krongard, Alex Brown & Sons and the CIA. Ruppert, however, describes this case in Crossing the Rubicon in full length as far as possible. [12]

In addition, there are also ways and means for insiders to veil their tracks. In order to be less obvious, "the insiders could trade small numbers of contracts. These could be traded under multiple accounts to avoid drawing attention to large trading volumes going through one single large account. They could also trade small volumes in each contract but trade more contracts to avoid drawing attention. As open interest increases, non-insiders may detect a perceived signal and increase their trading activity. Insiders can then come back to enter into more transactions based on a seemingly significant trade signal from the market. In this regard, it would be difficult for the CBOE to ferret out the insiders from the non-insiders, because both are trading heavily." [13]

The matter which needs clarification here is generally judged by Keiser as follows:

Max Keiser: My thought is that many (not all) of those who died on 9/11 were financial mercenaries - and we should feel the same about them as we feel about all mercenaries who get killed. The tragedy is that these companies mixed civilians with mercenaries, and that they were also killed. So have companies on Wall Street used civilians as human shields maybe?According to a report by Bloomberg published in early October 2001, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) began a probe into certain stock market transactions around 9/11 that included 38 companies, among them: American Airlines, United Airlines, Continental Airlines, Northwest Airlines, Southwest Airlines, Boeing, Lockheed Martin Corp., American Express Corp., American International Group, AXA SA, Bank of America Corp., Bank of New York Corp., Bear Stearns, Citigroup, Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc., Morgan Stanley, General Motors and Raytheon. [14]

So far, so good. In the same month, however, the San Francisco Chronicle newspaper reported that the SEC took the unprecedented step to deputize hundreds, if not even thousands of key stakeholders in the private sector for their investigation. In a statement that was sent to almost all listed companies in the US, the SEC asked the addressed companies to assign senior staff for the investigation, who would be aware of "the sensitive nature" of the case and could be relied on to "exercise appropriate discretion". [15]

In essence, it was about controlling information, not about provision and disclosure of facts. Such a course of action involves compromising consequences. Ruppert:

What happens when you deputize someone in a national security or criminal investigation is that you make it illegal for them to disclose publicly what they know. Smart move. In effect, they become government agents and are controlled by government regulations rather than their own conscience. In fact, they can be thrown into jail without a hearing if they talk publicly. I have seen this implied threat time after time with federal investigators, intelligence agents, and even members of United States Congress who are bound so tightly by secrecy oaths and agreements that they are not even able to disclose criminal activities inside the government for fear of incarceration. [16]Among the reports about suspected insider trading which are mentioned in Crossing the Rubicon/From the Wilderness is a list that was published under the heading "Black Tuesday: The World's Largest Insider Trading Scam?" by the Israeli Herzliyya International Policy Institute for Counterterrorism on September 21, 2001:

|