'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label long term. Show all posts

Showing posts with label long term. Show all posts

Wednesday, 3 July 2024

Monday, 22 March 2021

Thursday, 30 July 2020

All marriages are arranged

Sadhguru Jaggi Vasudev in The Indian Express

Arranged marriage is a wrong terminology, because all marriages are arranged. By whom is the only question. Whether your parents or friends arranged it, or a commercial website or dating app arranged it, or you arranged it – anyway, it is an arrangement.

The idea that arranged marriage is some kind of a slavery – well that depends on whether there is exploitation. There are exploitative people everywhere. Sometimes, even your parents themselves may be exploitative – they may be doing things for their own reasons, like their prestige, their wealth, their nonsense.

Recently, someone asked me about choosing a girl for their boy. One girl is well-educated and pretty, but another girl had a wealthy father. They asked me which they should choose. So I asked a simple question, “Do you want to marry the girl or someone’s wealth?” It depends on what is your priority. If your priority is such that someone’s wealth by marriage becomes yours and that is all that matters to you, that is fine. Well, that is the kind of life you have chosen.

Arranged marriage and divorce rates

The success of something is in the result. Luxembourg, a small country which is held as one of the most economically prosperous and free societies, has a divorce rate of eighty-seven per cent. In Spain, the divorce rate is around sixty-five per cent; Russia is at fifty-one per cent; United States, forty-six per cent. India: 1.5 per cent. You decide which works best.

Well, people may say the divorce rate here is low due to the social stigma associated with divorce, but definitely how it is arranged is also an important factor. When parents are the basis of organising the marriage, the success rate is a little better because they will think more long term. You may just like the way a girl is dressed and you want to get married today. Well, tomorrow morning you could realise you don’t want to have anything to do with her! When you are twenty, due to various compulsions or peer pressure, you may take decisions which will not last a lifetime. But sometimes you really hit it off with someone and it may work out – that is another matter.

Everything is an arrangement. You may think so many things about it, but it is arranged by your emotion, your greed, or by someone. It is an arrangement. It is best that it is arranged by responsible, sensible people, by those who are most concerned about your wellbeing, who have a larger reach. You cannot find the best man or woman in the world because we do not know where they are! With the limited contacts that we have, we can arrange something that is reasonably good. That is all it is.

If a young man or young woman wants to marry, who will they marry? Their contacts are very limited. Within those ten people that they know in their life, you marry one guy or girl. Within three months you will know what it really is. But in most countries, there is a law: if you make a mistake, at least two years you must suffer before you can divorce. It is like a jail term. Well, many religions have fixed it that you cannot divorce, that it is completely wrong. But where such religions are practiced, there the divorce rate is highest. So, neither God’s diktats nor the law is able to stop the breakups.

When parents organise a marriage, their judgement may not be the best, but they generally have your best interests in mind. If you have matured beyond your parents’ judgement or prejudice, that is different – now you can make your own decisions.

Conducting your marriage responsibly

When I married I did not know my wife’s full name. I did not know her father’s name. I did not know her caste. When I told my father that I wanted to marry her, he said, “What? You don’t know her father’s name? You don’t know who they are, or what they are? How can you marry her?”

I said, “I’m only marrying her. I’m not planning to marry any of the other things that come with her. Just her. That’s it.” I was absolutely clear about her potential and what she will bring to me, and she was helplessly in love from the first moment.

Though I never took anyone’s advice in my life, there are always self-appointed advisors who said, “You’re making the biggest mistake in your life, this is going to be a disaster.”

I said, “Whatever happens, whichever way it happens, it is for me either to make it a disaster or a success.” I knew this much.

Because who you marry, how you marry, which way it was arranged or by whom it was arranged is not important. How responsibly you exist – that is all there is. How you arrange the marriage is your choice. I’m not saying this or that is the way, but whichever way you do it, please conduct it responsibly, joyfully. You need to understand to fulfil your needs, physical, psychological, emotional, social and various other needs, you are coming together. If you always remember, “To fulfil my needs, I’m with you,” then you will conduct this responsibly. Initially, you may be like that, but after some time, you think he or she needs you; then you will start acting wantonly and, of course, ugliness will start in many different ways.

This happened. A young man and a young woman got engaged. So once the ring was slid on her finger, the young woman said to him, “You can lean on me to share your pains, your struggles. Whatever sufferings you go through, you can always share them with me.”

The guy said, “Well, I don’t have any struggles or pains or problems.”

She said, “Well, we are not yet married.”

If you think you are full of pain, struggles, and problems and need someone to lean on, there will be trouble. You know, they have been saying, marriages are made in heaven, but you are cooking hell within you. If you think someone else is going to fix you then there will be trouble for you, and of course, unfortunate consequences for the other person. If you make yourself into a joyful, wonderful human being, then you will see, your work, home and marriage will all be wonderful. Everything will be wonderful because you are!

Arranged marriage is a wrong terminology, because all marriages are arranged. By whom is the only question. Whether your parents or friends arranged it, or a commercial website or dating app arranged it, or you arranged it – anyway, it is an arrangement.

The idea that arranged marriage is some kind of a slavery – well that depends on whether there is exploitation. There are exploitative people everywhere. Sometimes, even your parents themselves may be exploitative – they may be doing things for their own reasons, like their prestige, their wealth, their nonsense.

Recently, someone asked me about choosing a girl for their boy. One girl is well-educated and pretty, but another girl had a wealthy father. They asked me which they should choose. So I asked a simple question, “Do you want to marry the girl or someone’s wealth?” It depends on what is your priority. If your priority is such that someone’s wealth by marriage becomes yours and that is all that matters to you, that is fine. Well, that is the kind of life you have chosen.

Arranged marriage and divorce rates

The success of something is in the result. Luxembourg, a small country which is held as one of the most economically prosperous and free societies, has a divorce rate of eighty-seven per cent. In Spain, the divorce rate is around sixty-five per cent; Russia is at fifty-one per cent; United States, forty-six per cent. India: 1.5 per cent. You decide which works best.

Well, people may say the divorce rate here is low due to the social stigma associated with divorce, but definitely how it is arranged is also an important factor. When parents are the basis of organising the marriage, the success rate is a little better because they will think more long term. You may just like the way a girl is dressed and you want to get married today. Well, tomorrow morning you could realise you don’t want to have anything to do with her! When you are twenty, due to various compulsions or peer pressure, you may take decisions which will not last a lifetime. But sometimes you really hit it off with someone and it may work out – that is another matter.

Everything is an arrangement. You may think so many things about it, but it is arranged by your emotion, your greed, or by someone. It is an arrangement. It is best that it is arranged by responsible, sensible people, by those who are most concerned about your wellbeing, who have a larger reach. You cannot find the best man or woman in the world because we do not know where they are! With the limited contacts that we have, we can arrange something that is reasonably good. That is all it is.

If a young man or young woman wants to marry, who will they marry? Their contacts are very limited. Within those ten people that they know in their life, you marry one guy or girl. Within three months you will know what it really is. But in most countries, there is a law: if you make a mistake, at least two years you must suffer before you can divorce. It is like a jail term. Well, many religions have fixed it that you cannot divorce, that it is completely wrong. But where such religions are practiced, there the divorce rate is highest. So, neither God’s diktats nor the law is able to stop the breakups.

When parents organise a marriage, their judgement may not be the best, but they generally have your best interests in mind. If you have matured beyond your parents’ judgement or prejudice, that is different – now you can make your own decisions.

Conducting your marriage responsibly

When I married I did not know my wife’s full name. I did not know her father’s name. I did not know her caste. When I told my father that I wanted to marry her, he said, “What? You don’t know her father’s name? You don’t know who they are, or what they are? How can you marry her?”

I said, “I’m only marrying her. I’m not planning to marry any of the other things that come with her. Just her. That’s it.” I was absolutely clear about her potential and what she will bring to me, and she was helplessly in love from the first moment.

Though I never took anyone’s advice in my life, there are always self-appointed advisors who said, “You’re making the biggest mistake in your life, this is going to be a disaster.”

I said, “Whatever happens, whichever way it happens, it is for me either to make it a disaster or a success.” I knew this much.

Because who you marry, how you marry, which way it was arranged or by whom it was arranged is not important. How responsibly you exist – that is all there is. How you arrange the marriage is your choice. I’m not saying this or that is the way, but whichever way you do it, please conduct it responsibly, joyfully. You need to understand to fulfil your needs, physical, psychological, emotional, social and various other needs, you are coming together. If you always remember, “To fulfil my needs, I’m with you,” then you will conduct this responsibly. Initially, you may be like that, but after some time, you think he or she needs you; then you will start acting wantonly and, of course, ugliness will start in many different ways.

This happened. A young man and a young woman got engaged. So once the ring was slid on her finger, the young woman said to him, “You can lean on me to share your pains, your struggles. Whatever sufferings you go through, you can always share them with me.”

The guy said, “Well, I don’t have any struggles or pains or problems.”

She said, “Well, we are not yet married.”

If you think you are full of pain, struggles, and problems and need someone to lean on, there will be trouble. You know, they have been saying, marriages are made in heaven, but you are cooking hell within you. If you think someone else is going to fix you then there will be trouble for you, and of course, unfortunate consequences for the other person. If you make yourself into a joyful, wonderful human being, then you will see, your work, home and marriage will all be wonderful. Everything will be wonderful because you are!

Friday, 18 May 2018

Struggling with revision? Here's how to prepare for exams more efficiently

Abby Young-Powell in The Guardian

If you’re one to put hours into revising for an exam only to be disappointed with the results, then you may need to rethink your revision methods. You could be wasting time on inefficient techniques, says Bradley Busch, a registered psychologist and director of InnerDrive. “You get people putting in lots of effort, but not in a directed way,” he says. Here are some of the common ways students unwittingly waste study time, and what experts recommend you do instead.

Re-reading and highlighting notes

Re-reading and highlighting notes may feel like work, but it often won’t achieve much. The same goes for spending hours drawing up a revision timetable. Instead, psychologists recommend a technique called retrieval practice. This is anything that makes your brain work to come up with an answer. It can include doing quizzes, multiple choice tests, and past papers. “To really learn something, you’ve got to transfer information from working memory into long term memory, where you can store and later retrieve it,” says David Cox, a neuroscientist and journalist. “Committing something to long term memory isn’t easy, so it shouldn’t feel easy.”

Last-minute cramming

Beware of the planning fallacy, which is our tendency to underestimate how much time we really need to do something. It leads to sitting outside the exam hall with two hours to spare, desperately cramming. This is not an effective way to learn. “The information you gain quickly, you can lose quickly too,” says Busch.

The opposite of cramming is spacing, which is the practice of spacing out your revision over time, doing little and often. So one hour a day for seven days is better than cramming seven hours into one day, for example. It’s also good to incorporate interleaving into your revision. This is a fancy way of saying you should mix up your subjects during a revision session. “It forces you to think about the problem and the strategy you come up with,” says Busch.

Making a study playlist

Sifting through the recommended study playlists on Spotify, trying to work out which songs will help you to concentrate, is usually a waste of time. But while listening to music can help you relax, and some students may have “trained” themselves to concentrate with it on, it’s still better to study in silence, Cox says. “You’re never going to be as productive having music on in the background, because it’s preventing your brain from acting at maximum capacity.”

Checking your phone

We may check our phones as often as once every 12 minutes. Obviously, this is a major distraction. That’s not all: research has shown that just having your phone in sight when you revise is enough to negatively affect your concentration, even if you don’t use it. And it’s a common trap to fall into. “I usually have my phone on silent mode, but to be honest, if it’s there I always check it,” says Chiara Fiorillo, who studies at City, University of London. Ideally it’s best to banish your phone to another room altogether.

If you’re one to put hours into revising for an exam only to be disappointed with the results, then you may need to rethink your revision methods. You could be wasting time on inefficient techniques, says Bradley Busch, a registered psychologist and director of InnerDrive. “You get people putting in lots of effort, but not in a directed way,” he says. Here are some of the common ways students unwittingly waste study time, and what experts recommend you do instead.

Re-reading and highlighting notes

Re-reading and highlighting notes may feel like work, but it often won’t achieve much. The same goes for spending hours drawing up a revision timetable. Instead, psychologists recommend a technique called retrieval practice. This is anything that makes your brain work to come up with an answer. It can include doing quizzes, multiple choice tests, and past papers. “To really learn something, you’ve got to transfer information from working memory into long term memory, where you can store and later retrieve it,” says David Cox, a neuroscientist and journalist. “Committing something to long term memory isn’t easy, so it shouldn’t feel easy.”

Last-minute cramming

Beware of the planning fallacy, which is our tendency to underestimate how much time we really need to do something. It leads to sitting outside the exam hall with two hours to spare, desperately cramming. This is not an effective way to learn. “The information you gain quickly, you can lose quickly too,” says Busch.

The opposite of cramming is spacing, which is the practice of spacing out your revision over time, doing little and often. So one hour a day for seven days is better than cramming seven hours into one day, for example. It’s also good to incorporate interleaving into your revision. This is a fancy way of saying you should mix up your subjects during a revision session. “It forces you to think about the problem and the strategy you come up with,” says Busch.

Making a study playlist

Sifting through the recommended study playlists on Spotify, trying to work out which songs will help you to concentrate, is usually a waste of time. But while listening to music can help you relax, and some students may have “trained” themselves to concentrate with it on, it’s still better to study in silence, Cox says. “You’re never going to be as productive having music on in the background, because it’s preventing your brain from acting at maximum capacity.”

Checking your phone

We may check our phones as often as once every 12 minutes. Obviously, this is a major distraction. That’s not all: research has shown that just having your phone in sight when you revise is enough to negatively affect your concentration, even if you don’t use it. And it’s a common trap to fall into. “I usually have my phone on silent mode, but to be honest, if it’s there I always check it,” says Chiara Fiorillo, who studies at City, University of London. Ideally it’s best to banish your phone to another room altogether.

Monday, 21 October 2013

Saving the planet from short-termism will take man-on-the-moon commitment

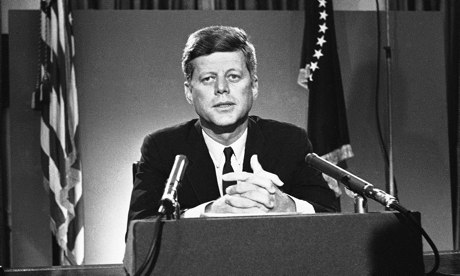

JFK's lunar vision is needed if business is to see the long-term benefits of greening the economy as well as the short-term costs

President John F Kennedy's moon speech was made in an age when both sides on Capitol Hill were prepared to invest in the future. Photograph: John Rous/AP

We choose to go to the moon. So said John F Kennedy in September 1962 as he pledged a manned lunar landing by the end of the decade.

The US president knew that his country's space programme would be expensive. He knew it would have its critics, but he took the long-term view. Warming to his theme in Houston that day, JFK went on: "We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organise and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win, and the others too."

That was the world's richest country at the apogee of its power in an age where both Democrats and Republicans were prepared to invest in the future. Kennedy's predecessor, Dwight Eisenhower, took a plan for a system of interstate highways and made sure it happened.

Contrast that with today's America, which looks less like the leader of the free world than a banana republic with a reserve currency. Planning for the long term now involves last-ditch deals on Capitol Hill to ensure the federal government can remain open until January and debts can be paid at least until February.

The US is not the only country with advanced short-termism. It merely provides the most egregious example of the disease. This is a world of fast food and short attention spans, of politicians so dominated by a 24/7 news agenda that they have lost the habit of planning for the long term.

Britain provides another example of the trend. Governments of both left and right have for years put energy policy in the "too hard to think about box". They have not been able to make up their minds whether to commit to renewables as Germany has done, or to nuclear as France has done. So, the nation of Rutherford is now prepared to have a totalitarian country take a majority stake in a new generation of nuclear power stations.

Politics, technology and human nature all militate in favour of kicking the can down the road. The most severe financial and economic crisis in more than half a century has further discouraged policymakers from raising their eyes from the present to the distant horizon.

Clearly, though, the world faces long-term challenges that will only become more acute through prevarication. These include coping with a bigger and ageing global population, ensuring growth is sustainable and equitable, providing resources to pay for modern transport and energy infrastructure, and reshaping international institutions so they represent the world as it is in the early 21st century rather than as it was in 1945.

Pascal Lamy had a stab at tackling some of these difficult issues last week when he presented the findings of the Oxford Martin Commission for Future Generations, which the former World Trade Organisation chief has been chairing for the past year.

The commission's report, Now for the Long Term, looks at some "mega trends" that will shape the world in the decades to come, and lists the challenges under five headings: society, resources, health, geopolitics, governance.

Change will be difficult, the study suggests, because problems are complex, institutions are inadequate, faith in politicians is low and short-termism is well-entrenched.

It cites examples of collective success, such as the Montreal convention to prevent ozone depletion, the establishment of the Millennium Development Goals, and the G20 action to prevent the great recession of 2008-09 turning into a full-blown global slump. It also cites examples of collective failure – fish stocks depletion, the deadlocked Copenhagenclimate change summit of 2009.

The report suggests a range of long-term ideas worthy of serious consideration. It urges a coalition between the G20, 30 companies and 40 cities to lead the fight against climate change. It would like "sunset clauses" for all publicly funded international institutions to ensure they are fit for purpose; removal of perverse subsidies on hydrocarbons and agriculture with the money redirected to the poor; introduction of CyberEx, an early warning platform aimed at preventing cyber attacks; a Worldstat statistical agency to collect and ensure quality of data; and investment in the younger generation through conditional cash transfers and job guarantees.

Lamy expressed concern that the ability to address challenges was being undermined by the absence of a collective vision for society. The purpose of the report, he said, was to build "a chain from knowledge to awareness to mobilising political energy to action".

Full marks for trying, but this is easier said than done. Take trade, where Lamy has spent the past decade, first as Europe's trade commissioner then as head of the WTO, trying to piece together a new multilateral deal. This is an area in which all 150-plus WTO members agree in principle about the need for greater liberalisation but in which it has proved impossible to reach agreement in talks that started in 2001.

Nor will a shakeup of the international institutions be plain sailing. It is a given that developing countries, especially the bigger ones such as China, India and Brazil, should have a bigger say in the way the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank are run. Yet it's proved hard to persuade developed world countries to cede some of their voting rights, and the deal is still being held up by US foot dragging. These, remember, are the low-hanging fruit.

Another conclave of the global great and good is looking at what should be done in the much trickier area of climate change. The premise of the Global Commission on the Economy and Climate is that nothing will be done unless finance ministers are convinced of the need for action, especially given the damage caused by a deep recession and sluggish recovery.

Instead of preaching to the choir the plan is to show how to achieve key economic objectives – growth, investment, secure public finances, fairer distribution of income – while at the same time protecting the planet. The pitch to finance ministers will be that tackling climate change will require plenty of upfront investment that will boost growth rather than harm it.

Will this approach work? Well, maybe. But it will require business to see the long-term benefits of greening the economy as well as the short-term costs, because that would lead to the burst of technological innovation needed to accelerate progress. And it will require the same sort of commitment it took to win a world war or put a man on the moon.

Friday, 15 February 2013

Tuesday, 12 February 2013

This Poundland ruling is a welcome blow to the Work Programme

It's invaluable that three judges have ruled in the Cait Reilly case against an appalling back-to-work system

Cait Reilly after winning her claim that requiring her to work for free was unlawful. Photograph: Cathy Gordon/PA

Before we get too excited about the judges' ruling in Reilly and Wilson v the secretary of state,

this is not a judgment against slavery or forced labour. Both Cait

Reilly and Jamieson Wilson lodged this appeal on the basis that, in

forcing them to do unpaid work or lose their benefits, the government

was breaching its own regulations.

You may think that there is a moral case to answer for the secretary of state, in pulling someone away from unpaid work in a sector they're interested in, forcing them instead to work unpaid stacking shelves in Poundland, with no training and no advancement of their skills, driving down wages for the rest of Poundland's employees while benefiting nobody but the retailer and the workfare provider. I know that's what I think.

You might think that when you train a skilled engineer to clean furniture – on the basis that the reason for his idleness was that he'd got out of the habit of work, that he needed to prove his mettle with whatever menial task you chose for him – there's a moral case to answer here, too. I'd agree.

But judges Black, Pill and Burnton haven't ruled on morality, they have merely ruled on nuts and bolts: Reilly was told that her scheme was mandatory, where in fact it was not. Wilson was told that if he refused to take part in a six-month work experience programme, he'd lose his benefits for that period. In fact, the maximum sanction would have been a two-week loss of benefits.

Nevertheless, though a ruling on slavery might have added some weight to it, this remains a punch in the face for this government, the Work Programme generally, and workfare in particular. Even the profile of these two cases significantly damages the reputation of this policy, whose raison d'etre is that long-term unemployment is the result of people getting out of the habit of work.

"What are the barriers that people have?" the employment minister Mark Hoban wondered aloud today on World at One. "One of the things people need to demonstrate to an employer is that they can turn up on time." This old chestnut – that long-term unemployment is the preserve of people who can't haul their sorry bones out of bed, must be countered all the time. The more cases we know about of unemployed people who are highly trained, gainfully occupied and routinely insulted by stupid workfare suggestions, the better.

On a practical note, people who've had their jobseeker's allowance stopped on grounds that are similar to Reilly or Wilson's can now claim the money back. This rights a grave social wrong, and delivers a sorely needed sanction to the workfare providers themselves, who understand nothing but money, and might finally question their deficiencies with cash at stake.

But most importantly, there is a growing sense that this back-to-work system is corrupt – my colleague Shiv Malik discovered recently that people on unpaid schemes were being counted as employed to massage the government's figures, even though by any reasonable person's understanding, they were not. Then the BBC revealed that people were being told to declare themselves "self-employed", even when they were simply without work, on the false basis that they could claim more in in-work benefits than JSA – the real benefit, of course, accruing to the Work Programme provider who could then claim them as having been "helped".

All the statistics released about the Work Programme show execrable results, and yet we've heard nothing about penalties, or remaking the contracts, or rethinking the system. There is a creeping sense that this is turning into a cash cow for the private sector, a get-out-clause for the government ("we've spent all this money, if people can't get jobs despite our help, it's because they are inadequate"), and unemployed people will be left at the bottom, ceaselessly harassed by a totally specious narrative in which their laziness beggars a try-hard administration.

A judge, casting doubt on all this in a sober way, is invaluable – three judges, better still. It makes me want to shake the legal profession by its giant hand.

You may think that there is a moral case to answer for the secretary of state, in pulling someone away from unpaid work in a sector they're interested in, forcing them instead to work unpaid stacking shelves in Poundland, with no training and no advancement of their skills, driving down wages for the rest of Poundland's employees while benefiting nobody but the retailer and the workfare provider. I know that's what I think.

You might think that when you train a skilled engineer to clean furniture – on the basis that the reason for his idleness was that he'd got out of the habit of work, that he needed to prove his mettle with whatever menial task you chose for him – there's a moral case to answer here, too. I'd agree.

But judges Black, Pill and Burnton haven't ruled on morality, they have merely ruled on nuts and bolts: Reilly was told that her scheme was mandatory, where in fact it was not. Wilson was told that if he refused to take part in a six-month work experience programme, he'd lose his benefits for that period. In fact, the maximum sanction would have been a two-week loss of benefits.

Nevertheless, though a ruling on slavery might have added some weight to it, this remains a punch in the face for this government, the Work Programme generally, and workfare in particular. Even the profile of these two cases significantly damages the reputation of this policy, whose raison d'etre is that long-term unemployment is the result of people getting out of the habit of work.

"What are the barriers that people have?" the employment minister Mark Hoban wondered aloud today on World at One. "One of the things people need to demonstrate to an employer is that they can turn up on time." This old chestnut – that long-term unemployment is the preserve of people who can't haul their sorry bones out of bed, must be countered all the time. The more cases we know about of unemployed people who are highly trained, gainfully occupied and routinely insulted by stupid workfare suggestions, the better.

On a practical note, people who've had their jobseeker's allowance stopped on grounds that are similar to Reilly or Wilson's can now claim the money back. This rights a grave social wrong, and delivers a sorely needed sanction to the workfare providers themselves, who understand nothing but money, and might finally question their deficiencies with cash at stake.

But most importantly, there is a growing sense that this back-to-work system is corrupt – my colleague Shiv Malik discovered recently that people on unpaid schemes were being counted as employed to massage the government's figures, even though by any reasonable person's understanding, they were not. Then the BBC revealed that people were being told to declare themselves "self-employed", even when they were simply without work, on the false basis that they could claim more in in-work benefits than JSA – the real benefit, of course, accruing to the Work Programme provider who could then claim them as having been "helped".

All the statistics released about the Work Programme show execrable results, and yet we've heard nothing about penalties, or remaking the contracts, or rethinking the system. There is a creeping sense that this is turning into a cash cow for the private sector, a get-out-clause for the government ("we've spent all this money, if people can't get jobs despite our help, it's because they are inadequate"), and unemployed people will be left at the bottom, ceaselessly harassed by a totally specious narrative in which their laziness beggars a try-hard administration.

A judge, casting doubt on all this in a sober way, is invaluable – three judges, better still. It makes me want to shake the legal profession by its giant hand.

Wednesday, 6 February 2013

Understanding Germany and its Mittelstand ethos

Germany is right: there is no right to profit, but the right to work is essential

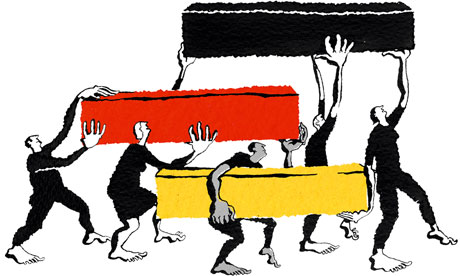

The strength of Germany lies in its medium-sized manufacturing firms, whose ethos includes being socially useful

'The objective of

every German business leader is to earn trust – from employees,

customers, suppliers and society as a whole.' illustration by Belle

Mellor

People talk too much about the economy and not enough about

jobs. When economists, academics and bankers are allowed to lead the

debate, the essential human element goes missing. This is neither

healthy nor practical.

Unemployment should be our prime concern. Spain, with youth joblessness close to 50%, is in the gravest crisis, but there is hardly a government on the planet that is not wondering what it can do to guide school-leavers into work, exploit the skills of older workers, and avoid the apathy and alienation of the jobless, which undermines not just the economy but also the social fabric.

There may be no definitive answer but, over the past half-century, Germany has come closest to finding it. Its postwar economic miracle was impressive, but its more recent ability to ride out recessions and absorb the costs of reunification is, perhaps, even more remarkable. Germany was not immune to the economic crisis of 2008-9, but the jobless rate rose more slowly than elsewhere in Europe. Although in recent months it has edged up towards 6.9%, it remains well below the euro area's 11.7% average. Germany's resilience springs from the strength of its medium-sized, often family-owned manufacturing companies, collectively known as the Mittelstand, which account for 60% of the workforce and 52% of Germany's GDP. So what can we learn from the Germans?

The enduring success of the Mittelstand has been well documented but rarely emulated. The standard excuse is that it is rooted in German history and culture and therefore unexportable. At a time when so much business is conducted on a global scale, via globally accessible media, this excuse is wearing thin.

Let me highlight some of the features unique to the Mittelstand model that I believe everyone should learn from – and imitate if they can. The first is what we might call the Mittelstand ethos – that business is a constructive enterprise that aims to be socially useful. Making a profit is not an end in itself: job creation, client satisfaction and product excellence are just as fundamental. Taking on debt is treated with suspicion. The objective of every business leader is to earn trust – from employees, customers, suppliers and society as a whole. This ethos chimes with the values of prudence and responsibility with which every schoolteacher hopes to imbue their pupils. Consequently, about half of all German high-school students move on to train in a trade. Business and education are natural bedfellows.

The second essential feature of the Mittelstand model is the collaborative spirit that generally exists between employer and employees. This can be dated back to the welfare state that Chancellor Otto von Bismarck established in the late 19th century to head off what he saw as the menace of socialism. Its modern-day equivalent is the system of works councils, which ensures that employees' interests are safeguarded, whether or not they belong to a trade union. German workers expect their employers to keep training them, enhancing their skills. In the post-reunification recession, it seemed only natural to German workers to offer flexibility on wages and hours in return for greater job security. More recently the government protected jobs by subsidising companies that cut hours rather than staff.

A third feature of the Mittelstand model is the determination of German companies to build for the long term. To this end, they tend to keep core functions such as engineering and project management in-house, while outsourcing production whenever this proves more efficient. Mittelstand companies are overwhelmingly privately owned, and thus largely free of pressure to provide shareholder returns. This makes them readier to innovate, and invest a larger proportion of their revenues in R&D. There are Mittelstand companies that file more patents in a year than do some entire European countries. It is one of the underlying reasons for their exporting success, even when their goods seem expensive.

Finally, German companies work closely with their suppliers. This has proved especially valuable in developing Sino-German trade. Unlike most of their international competitors, they are happy to take suppliers' representatives on trade missions. The result is that they can guarantee swift and sure supplies of components and other products. Chinese customers are not the only ones willing to pay extra for this kind of service excellence.

Of course, there are other factors that lie behind the success of the Mittelstand and of the German economy as a whole. Both the economy and political system are highly decentralised, with the result that local banks, businesses, entrepreneurs and politicians know and understand each other, making everyday co-operation easier – while, at the national level, Germany's leaders rarely miss an opportunity to promote their country's industry abroad.

Nonetheless, there is much that non-Germans could learn from. To close the gap between education and business, companies should take a greater interest in their local schools and colleges. If you haven't got spare cash for sponsoring gyms or computer equipment, go and talk to sixth-formers or degree students about what you do. Find out what graduates aspire to. It will help you to work out how to attract the next generation.

If you want to get more out of your employees and suppliers, consult them; invite them into your confidence. Don't complain: "We're not like the Germans. It won't work here." Think of a different way. Try harder.

The same applies to governments. Let me mention one simple legislative option. In German law, the owner of a family business who passes it on to the next generation can avoid paying inheritance tax if, during their tenure, they have increased employment and thereby benefited the economy. What better signal could a government give than by favouring those who create employment?

There is no question in my mind about which is the single most important feature of the Mittelstand model – its underlying ethos, which is based not on dry economic theory, but on everyday, practical humanity. The notion that business should be socially useful may have sprung from Germany's postwar conscience, but it has resonance now, when so many of our citizens are still suffering from the aftermath of the credit crunch and the failures of leadership it exposed.

There is no right to make a profit, and profit has no intrinsic value. But there is a right to work, and it is fundamental to human dignity. Without an opportunity to contribute with our hands or brains, we have no stake in society and our governments lack true legitimacy. There can be no more urgent challenge for our leaders. The title of the next G8 summit should be a four-letter word that everyone understands – jobs.

Unemployment should be our prime concern. Spain, with youth joblessness close to 50%, is in the gravest crisis, but there is hardly a government on the planet that is not wondering what it can do to guide school-leavers into work, exploit the skills of older workers, and avoid the apathy and alienation of the jobless, which undermines not just the economy but also the social fabric.

There may be no definitive answer but, over the past half-century, Germany has come closest to finding it. Its postwar economic miracle was impressive, but its more recent ability to ride out recessions and absorb the costs of reunification is, perhaps, even more remarkable. Germany was not immune to the economic crisis of 2008-9, but the jobless rate rose more slowly than elsewhere in Europe. Although in recent months it has edged up towards 6.9%, it remains well below the euro area's 11.7% average. Germany's resilience springs from the strength of its medium-sized, often family-owned manufacturing companies, collectively known as the Mittelstand, which account for 60% of the workforce and 52% of Germany's GDP. So what can we learn from the Germans?

The enduring success of the Mittelstand has been well documented but rarely emulated. The standard excuse is that it is rooted in German history and culture and therefore unexportable. At a time when so much business is conducted on a global scale, via globally accessible media, this excuse is wearing thin.

Let me highlight some of the features unique to the Mittelstand model that I believe everyone should learn from – and imitate if they can. The first is what we might call the Mittelstand ethos – that business is a constructive enterprise that aims to be socially useful. Making a profit is not an end in itself: job creation, client satisfaction and product excellence are just as fundamental. Taking on debt is treated with suspicion. The objective of every business leader is to earn trust – from employees, customers, suppliers and society as a whole. This ethos chimes with the values of prudence and responsibility with which every schoolteacher hopes to imbue their pupils. Consequently, about half of all German high-school students move on to train in a trade. Business and education are natural bedfellows.

The second essential feature of the Mittelstand model is the collaborative spirit that generally exists between employer and employees. This can be dated back to the welfare state that Chancellor Otto von Bismarck established in the late 19th century to head off what he saw as the menace of socialism. Its modern-day equivalent is the system of works councils, which ensures that employees' interests are safeguarded, whether or not they belong to a trade union. German workers expect their employers to keep training them, enhancing their skills. In the post-reunification recession, it seemed only natural to German workers to offer flexibility on wages and hours in return for greater job security. More recently the government protected jobs by subsidising companies that cut hours rather than staff.

A third feature of the Mittelstand model is the determination of German companies to build for the long term. To this end, they tend to keep core functions such as engineering and project management in-house, while outsourcing production whenever this proves more efficient. Mittelstand companies are overwhelmingly privately owned, and thus largely free of pressure to provide shareholder returns. This makes them readier to innovate, and invest a larger proportion of their revenues in R&D. There are Mittelstand companies that file more patents in a year than do some entire European countries. It is one of the underlying reasons for their exporting success, even when their goods seem expensive.

Finally, German companies work closely with their suppliers. This has proved especially valuable in developing Sino-German trade. Unlike most of their international competitors, they are happy to take suppliers' representatives on trade missions. The result is that they can guarantee swift and sure supplies of components and other products. Chinese customers are not the only ones willing to pay extra for this kind of service excellence.

Of course, there are other factors that lie behind the success of the Mittelstand and of the German economy as a whole. Both the economy and political system are highly decentralised, with the result that local banks, businesses, entrepreneurs and politicians know and understand each other, making everyday co-operation easier – while, at the national level, Germany's leaders rarely miss an opportunity to promote their country's industry abroad.

Nonetheless, there is much that non-Germans could learn from. To close the gap between education and business, companies should take a greater interest in their local schools and colleges. If you haven't got spare cash for sponsoring gyms or computer equipment, go and talk to sixth-formers or degree students about what you do. Find out what graduates aspire to. It will help you to work out how to attract the next generation.

If you want to get more out of your employees and suppliers, consult them; invite them into your confidence. Don't complain: "We're not like the Germans. It won't work here." Think of a different way. Try harder.

The same applies to governments. Let me mention one simple legislative option. In German law, the owner of a family business who passes it on to the next generation can avoid paying inheritance tax if, during their tenure, they have increased employment and thereby benefited the economy. What better signal could a government give than by favouring those who create employment?

There is no question in my mind about which is the single most important feature of the Mittelstand model – its underlying ethos, which is based not on dry economic theory, but on everyday, practical humanity. The notion that business should be socially useful may have sprung from Germany's postwar conscience, but it has resonance now, when so many of our citizens are still suffering from the aftermath of the credit crunch and the failures of leadership it exposed.

There is no right to make a profit, and profit has no intrinsic value. But there is a right to work, and it is fundamental to human dignity. Without an opportunity to contribute with our hands or brains, we have no stake in society and our governments lack true legitimacy. There can be no more urgent challenge for our leaders. The title of the next G8 summit should be a four-letter word that everyone understands – jobs.

Sunday, 30 September 2012

We need a revolution in how our companies are owned and run

The second of this series on a new capitalism calls for a culture dedicated to long-term, ethical goals

Rolls Royce: almost our last remaining great industrial company. Photograph: Simon Stuart-Miller/guardian.co.uk

Twenty years ago, Britain's greatest industrial companies were ICI and GEC. A third, Rolls-Royce, secured from hostile takeover by a government golden share, had a board that was boringly committed to research and development and to investing in its business. ICI and GEC, under colossal pressure from footloose shareholders to deliver high short-term profits, tried to wheel and deal their way to success. Neither now exists. Rolls Royce, free from concerns about hourly movements in its share price, has gone on to be almost our last remaining great industrial company.

Britain, as the Kay review on the equity markets reported, has far too few Rolls-Royces. Instead the report identified a lengthening list of companies – Marks and Spencer, Royal Bank of Scotland, BP, GlaxoSmithKline, Lloyds and now BAE – which have made grave strategic errors, taken ethical short cuts or launched ill-judged takeovers, hoping to benefit their uncommitted tourist shareholders. Their competitors in other countries, with different ownership structures and incentives, have survived and prospered.

It is an unreported crisis of ownership that goes to the heart of our current ills. Over the last decade, a fifth of quoted companies have evaporated from the London Stock Exchange, the largest cull in our history. Virtually no new risk capital is sought from the stock market or being offered across the spectrum of companies. A share is now held for an average of seven months. Britain has no indigenous quoted company in the fields of car, chemical or building materials. They are all owned overseas, with design and research and development travelling abroad as well.

The stock market has descended into a casino, served by a vast industry of intermediaries – agents, trustees, investment managers, registrars and advisers of all sorts – who have grown fat from opaque fees. It has become a transmission mechanism for highly short-term expectations of profit driven into the boardroom. Directors' pay has been linked to share price performance, offering them the prospect of stunning fortunes. As a result, R&D is consistently undervalued.

British companies are now hoarding some £800bn in cash, cash they would rather use buying back their own shares than committing to investment. We have allowed a madhouse to develop. An important reason why Britain is at the bottom of the league table for investment and innovation is the way our companies are owned or, rather, notowned.

It is a crisis of commitment. Too few shareholders are committed to the companies they allegedly "own". They consider their shares either casino chips to be traded in the immediate future or as no more than a contract offering the opportunity of dividends in certain industries and countries; this requires no engagement in how those profits and dividends are generated. British law and corporate governance rules demand the narrowest interpretation of investors' and directors' duties: to maximise short-term profits while having minimal associated responsibilities.

The company is conceived as nothing more than a network of short-term contracts. Any shareholder – from a transient day trader to a long-term investor – has the same standing in law. American directors' ability to defend their company from hostile takeover or German directors having to live – horrors – with trade union representatives on their supervisory boards are seen as obstacles to enterprise that Britain must not go near. But companies and wealth generation, as Professor Colin Mayer argues in his important forthcoming book Firm Commitment, are about co-creation, sharing risk and long-term trust relationships: Britain's refusal to embrace these core truths is toxic. Companies were originally invented as legal structures to enable groups of investors to come together, committing to share risk around a shared goal and so make profit for themselves, but delivering wider economic and social benefits in the process. Incorporation was understood to be associated with obligations: a company had to declare its purpose before earning a licence to trade. There existed a mutual deal between society and company.

No game-changing improvement in British investment and innovation is possible without a return to engagement, stewardship and commitment. Limited liability should not be a charter to do what you like. It must be conditional on a core business purpose, along with the creation of trustees to guard it. Directors' obligations should be legally redefined to deliver on this purpose. What's more, every shareholder should be required to vote, with voting strength, as Mayer argues, increasing for the number of years the share is held.

To solve the problem that individual shareholders – even savings institutions – do not have sufficient muscle nor sufficient incentive to engage with managements, voting rights could be aggregated and given to new mutuals. These would support directors in delivering their corporate purpose, a proposal made by the Ownership Commission I chaired. Companies would become trust companies, with a stewardship code. The priority in takeovers would be the best future for the business, not the ambition to please the last hedge fund to take a short-term position.

Stakeholders should also have a voice in how the company is run. In Germany, a company's bankers and its employee representatives have seats on the supervisory board. Why not copy success rather than continue with our failed system? The Kay review's proposals to stop quarterly profit reporting, while a useful first step, do not address the core of the problem. The company has become a dysfunctional organisational construct that needs root-and-branch reform.

As part of the reform, Britain also needs more co-operatives, more employee-owned companies and more family-owned firms. It needs to be more attentive to which foreign companies own our assets and for what purpose. It is an ownership revolution to match the revolution in finance proposed last week. Together with an innovation revolution – see next week – the British economy could at last begin to deliver its promise.

Thursday, 23 February 2012

It's time to start talking to the City

A radical reform of the financial sector can only be achieved if we know what kind of capitalism we want

Last week I delivered a lecture on my latest book to about 150 people from the financial industry at the London Stock Exchange. The event was not organised or endorsed by the LSE itself, but the venue was quite poignant for me, given that a few months ago I did the same thing on the other side of the barricade, so to speak, at the Occupy London Stock Exchange movement.

At the exchange I made two proposals I knew may not be popular with the audience. My first was that we need to completely change the way we run our corporations, especially in the UK and the US. I started from the observation that financial deregulation since the 1980s has greatly increased the power of shareholders by expanding the options open to them, both geographically and in terms of product choice. Such deregulation was particularly advanced in Britain and America, making them the homes of "shareholder capitalism".

With greater abilities to move around, shareholders have begun to adopt increasingly short time horizons. As Prem Sikka wrote in the Guardian in December 2011, the average shareholding period in UK firms fell from about five years in the mid-1960s to 7.5 months in 2007. The figure for UK banks had fallen to three months by 2008 (although it is up to about two years now).

In order to satisfy impatient shareholders, managers have maximised short-term profits by squeezing other "stakeholders", such as workers and suppliers, and by minimising investments, whose costs are immediate but whose returns are remote. Such strategy does long-term damages by demoralising workers, lowering supplier qualities, and making equipment outmoded. But the managers do not care because their pay is linked to short-term equity prices, whose maximisation is what short term-oriented shareholders want.

That is not all. An increasing proportion of profits are distributed to shareholders through dividends and share buybacks (firms buying their own shares to prop up their prices). According to William Lazonick – a leading authority on this issue – between 2001 and 2010, top UK firms (86 companies that are included in the S&P Europe 350 index) distributed 88% of their profits to shareholders in dividends (62%) and share buybacks (26%).

During the same period, top US companies (459 of those in the S&P 500) paid out an even greater proportion to shareholders: 94% (40% in dividends and 54% in buybacks). The figure used to be just over 50% in the early 80s (about 50% in dividends and less than 5% in buybacks).

The resulting depletion in retained profit, traditionally the biggest source of corporate investments, has dramatically undermined these corporations' abilities to invest, further weakening their long-term competitiveness. Therefore, I concluded, unless we significantly restrict the freedom of movement for shareholders, through financial reregulation, and reward managers according to more long term-oriented performance measures than share prices, companies will continue to be managed in a way that undermines their own viability and weakens the national economy in the long run.

My second proposal was that, in order to improve the stability of our financial system, we need to radically simplify it. I argued that financial deregulation in the last 30 years led to the proliferation of complex financial derivatives. This has created a financial system whose complexity has far outstripped our ability to control it, as dramatically demonstrated by the 2008 financial crisis.

Drawing on the works of Herbert Simon, the 1978 Nobel economics laureate and a founding father of the study of artificial intelligence, I pointed out that often the crucial constraint on good decision-making is not the lack of information but our limited mental capability, or what Simon called "bounded rationality". Given our bounded rationality, I asserted, the only way to increase the stability of our financial system is to make it simpler. And the most important action to take is to restrict, or even ban, complex and risky financial instruments through the financial world equivalent of the drugs approval procedure.

The reactions of my audience were rather surprising. Not only did nobody challenge my proposals, but many agreed with me. Yes, they said, "quarterly capitalism" has been destructive. True, they related, we've seen too many derivative products that few people understood. And, yes, many of those products have been socially harmful.

It seems that, as it is wrong to label the Occupy movement as anti-capitalist, it is misleading to characterise the financial industry as being in denial about the need for reform. I am not naive enough to think that the people who came to my lecture are typical of the financial industry. However, a surprisingly large number of them acknowledged the problems of short-termism and excessive complexity that their industry has generated to the detriment of the rest of the economy – and ultimately to its own detriment, as the financial industry cannot thrive alone.

The rest of us need to have a closer dialogue with reform-minded people in the financial industry. They are the ones who can generate greater political acceptance of reforms among their colleagues and who can also help us devise technically competent reform proposals. After all, without a degree of "changes from within", no reform can be truly durable.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)