'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label collaboration. Show all posts

Showing posts with label collaboration. Show all posts

Sunday, 10 September 2023

Thursday, 14 May 2020

Any Covid-19 vaccine must be treated as a global public good

David Pilling in The Financial Times

Imagine if, in a year’s time, 300m doses of a safe and effective Covid-19 vaccine have been manufactured in Donald Trump’s America, Xi Jinping’s China or Boris Johnson’s Britain. Who is going to get them? What are the chances that a nurse in India, or a doctor in Brazil, let alone a bus driver in Nigeria or a diabetic in Tanzania, will be given priority? The answer must be virtually nil.

The ugly battle between nations over limited supplies of tests and personal protective equipment will be a sideshow compared to the scramble over a vaccine. Yet if a vaccine is to be anything like the silver bullet that some imagine, it will have to be available to the world’s poor as well as to its rich.

Any vaccine should be deployed to create the maximum possible benefit to public health. That will mean prioritising doctors, nurses and other frontline workers, as well as those most vulnerable to the disease, no matter where they live or how much they can afford.

It will also mean deploying initially limited quantities of vaccine in order to snuff out clusters of infection by encircling them with a “curtain” of immunised people — as was done successfully against Ebola last year in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

With Covid-19, this looks like a pipe dream. Far from bringing the world together, the pandemic has exposed a crisis of international disunity. The World Health Organization is only as good as its member states allow. That it finds itself squeezed between China and the US when humanity is facing its worst pandemic in 100 years, is a sign of the broken international order.

How, under such circumstances, can we possibly conceive of a vaccine policy that is global, ethical and effective?

There are precedents. The principle of access to medicines was established with the HIV-Aids pandemic, in which life-saving medicines were originally priced far above the ability of patients in Africa and other parts of the developing world to pay.

But in 2001, in the so-called Doha declaration on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, the World Trade Organization made it clear that governments could override patents in public health emergencies. Largely as a result, a tiered pricing system has developed in which drug companies make profits in richer countries while allowing medicines to be sold more cheaply in poorer ones.

There are also tried-and-tested methods of funding immunisation campaigns that have saved literally millions of lives in Africa, Asia and Latin America. Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, was founded in 2000 to address market failures. It guarantees the purchase of a set number of vaccine doses so that companies can manufacture existing, or develop new, vaccines knowing there will be a market for their product.

Along similar lines, 40 governments this month pledged $8bn to speed up the development, production and equitable deployment of Covid-19 vaccines, as well as diagnostics and therapeutics. There are already more than 80 candidates for a Covid-19 vaccine, with some of these now in human trials.

Then there is manufacturing. Lack of diagnostics and PPE has exposed the flaws of a just-in-time system that builds in no redundancy. Vaccine capacity must be built up now, even if that means some of it will go to waste. Nor can existing capacity simply be given over to a putative Covid-19 vaccine. That could unwittingly unleash outbreaks of previously controlled diseases, such as mumps or rubella.

Manufacturing will also have to be dispersed geographically to ensure a vaccine can be deployed globally.

Most vaccines are international collaborations. One against Ebola was discovered in Canada, developed in the US and manufactured in Germany. It is unlikely — and certainly undesirable — that any one country will be able to claim a Covid-19 vaccine all to itself.

Even if a successful candidate is developed, not everyone will want to take it.

Heidi Larson, director of the Vaccine Confidence Project, says surveys show that up to 9 per cent of British people, 18 per cent of Austrians and 20 per cent of Swiss would not agree to be immunised. Trust in vaccines is generally higher in the developing world, where the impact of infectious disease is more obvious. But here too there could be resistance, particularly if people suspect they are being used as guinea pigs.

The vaccine against a fictional pandemic in the 2011 film Contagion is distributed through a lottery based on birth date. When a vaccine against a real-life Covid-19 is found, it must be deployed as a global public good.

Health experts estimate it will cost some $20bn to vaccinate everyone on earth, equivalent to roughly two hours of global output. This is the best bargain in the world. Let us hope the world can recognise it.

Imagine if, in a year’s time, 300m doses of a safe and effective Covid-19 vaccine have been manufactured in Donald Trump’s America, Xi Jinping’s China or Boris Johnson’s Britain. Who is going to get them? What are the chances that a nurse in India, or a doctor in Brazil, let alone a bus driver in Nigeria or a diabetic in Tanzania, will be given priority? The answer must be virtually nil.

The ugly battle between nations over limited supplies of tests and personal protective equipment will be a sideshow compared to the scramble over a vaccine. Yet if a vaccine is to be anything like the silver bullet that some imagine, it will have to be available to the world’s poor as well as to its rich.

Any vaccine should be deployed to create the maximum possible benefit to public health. That will mean prioritising doctors, nurses and other frontline workers, as well as those most vulnerable to the disease, no matter where they live or how much they can afford.

It will also mean deploying initially limited quantities of vaccine in order to snuff out clusters of infection by encircling them with a “curtain” of immunised people — as was done successfully against Ebola last year in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

With Covid-19, this looks like a pipe dream. Far from bringing the world together, the pandemic has exposed a crisis of international disunity. The World Health Organization is only as good as its member states allow. That it finds itself squeezed between China and the US when humanity is facing its worst pandemic in 100 years, is a sign of the broken international order.

How, under such circumstances, can we possibly conceive of a vaccine policy that is global, ethical and effective?

There are precedents. The principle of access to medicines was established with the HIV-Aids pandemic, in which life-saving medicines were originally priced far above the ability of patients in Africa and other parts of the developing world to pay.

But in 2001, in the so-called Doha declaration on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, the World Trade Organization made it clear that governments could override patents in public health emergencies. Largely as a result, a tiered pricing system has developed in which drug companies make profits in richer countries while allowing medicines to be sold more cheaply in poorer ones.

There are also tried-and-tested methods of funding immunisation campaigns that have saved literally millions of lives in Africa, Asia and Latin America. Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, was founded in 2000 to address market failures. It guarantees the purchase of a set number of vaccine doses so that companies can manufacture existing, or develop new, vaccines knowing there will be a market for their product.

Along similar lines, 40 governments this month pledged $8bn to speed up the development, production and equitable deployment of Covid-19 vaccines, as well as diagnostics and therapeutics. There are already more than 80 candidates for a Covid-19 vaccine, with some of these now in human trials.

Then there is manufacturing. Lack of diagnostics and PPE has exposed the flaws of a just-in-time system that builds in no redundancy. Vaccine capacity must be built up now, even if that means some of it will go to waste. Nor can existing capacity simply be given over to a putative Covid-19 vaccine. That could unwittingly unleash outbreaks of previously controlled diseases, such as mumps or rubella.

Manufacturing will also have to be dispersed geographically to ensure a vaccine can be deployed globally.

Most vaccines are international collaborations. One against Ebola was discovered in Canada, developed in the US and manufactured in Germany. It is unlikely — and certainly undesirable — that any one country will be able to claim a Covid-19 vaccine all to itself.

Even if a successful candidate is developed, not everyone will want to take it.

Heidi Larson, director of the Vaccine Confidence Project, says surveys show that up to 9 per cent of British people, 18 per cent of Austrians and 20 per cent of Swiss would not agree to be immunised. Trust in vaccines is generally higher in the developing world, where the impact of infectious disease is more obvious. But here too there could be resistance, particularly if people suspect they are being used as guinea pigs.

The vaccine against a fictional pandemic in the 2011 film Contagion is distributed through a lottery based on birth date. When a vaccine against a real-life Covid-19 is found, it must be deployed as a global public good.

Health experts estimate it will cost some $20bn to vaccinate everyone on earth, equivalent to roughly two hours of global output. This is the best bargain in the world. Let us hope the world can recognise it.

Monday, 8 July 2019

Why a leader’s past record is no guide to future success

Successful leadership depends on context, collaboration and character writes Andrew Hill in The FT

“There goes that queer-looking fish with the ginger beard again. Do you know who he is? I keep seeing him creep about this place like a lost soul with nothing better to do.”

“There goes that queer-looking fish with the ginger beard again. Do you know who he is? I keep seeing him creep about this place like a lost soul with nothing better to do.”

That was the verdict of the then Bank of England governor on Montagu Norman, who, five years later, was to take over the top job. “Nothing in his background suggested that he would be well suited to the work of a central banker,” Liaquat Ahamed wrote in his prizewinning book Lords of Finance.

Plenty in Christine Lagarde’s background suggests she will be much better suited to run the European Central Bank: her political nous, her communication skills, her leadership of the International Monetary Fund through turbulent financial times.

Critics, though, have focused on the former corporate lawyer and finance minister’s lack of deep academic economic training, and her dearth of experience with the technicalities of monetary policy.

But how much should the past record of a candidate be a guide for how they will handle their next job? Not as much as we might think.

The truth is that successful leadership depends on context, collaboration and character as much as qualifications. For all the efforts to codify and computerise the specifications of important jobs, the optimal chemistry of experience, aptitude, potential, and mindset remains hard to define. Throw in the imponderable future in which such leaders are bound to operate and it is no wonder that sometimes the seemingly best-qualified stumble, while the qualification-free thrive.

For one thing, even if the challenge confronting a leader looks the same as one they handled in the past, it is very rarely identical — and nor is the leader. That is one reason big companies offer their most promising executives experience across countries, cultures and operations, from finance to the front line, and why some recruiters emphasise potential as much as the formal résumé of their candidates.

Curiosity is a big predictor of potential — and of success — according to Egon Zehnder, the executive search company. It asks referees what the candidate they have backed is really curious about. “It is a question that takes people aback, so they have to think anew about that person,” Jill Ader, chairwoman, told me recently.

I think there are strong reasons to back master generalists for senior roles. Polymathic leaders offer alternative perspectives and may even be better at fostering innovation, according to one study. In his new book Range, David Epstein offers this warning against over-specialisation: “Everyone is digging deeper into their own trench and rarely standing up to look in the next trench over.”

Take this to the other extreme of ignoring specialist qualifications, however, and you are suddenly in the world of blaggers, blowhards and blackguards, who bluff their way up the leadership ladder until the Peter Principle applies, and a further rise is prohibited by their own incompetence.

The financial crisis exposed the weaknesses of large banks, such as HBOS and Royal Bank of Scotland in the UK, chaired by non-bankers. Some of the same concerns about a dearth of deep financial qualifications now nag at the leaders of fintech companies, whose promise is based in part on their boast that they will be “different” from longer established incumbents.

In a flailing search for the reasons for its current political mess, the UK has blamed the self-confident dilettantism of some Oxford university graduates, while the US bemoans the superficial attractions of stars of television reality shows. These parallel weaknesses for pure bluster over proven expertise have brought us Boris Johnson and Donald Trump, respectively.

A plausible defence of both Mr Johnson and Mr Trump is that they should be able to play to their specific strengths, while surrounding themselves with experts who can handle the technical work.

Ms Lagarde, too, will want to draw on the team of experts around her. She is wise enough to know she cannot rely on silky political skills and neglect the plumbing of monetary policy.

At the same time, history suggests she should not assume her paper credentials or wide experience will be enough to guarantee success in Frankfurt. The Bank of England’s Norman was eccentric and neurotic, and his counterpart at the Banque de France, Émile Moreau, had a “quite rudimentary and at times confused” understanding of monetary economics, whereas Benjamin Strong at the New York Federal Reserve, was a born leader, and Hjalmar Schacht of Germany’s Reichsbank “came to the job with an array of qualifications”.

Yet together this quartet of the under- and overqualified made a series of mistakes that pitched the world into the Great Depression.

Plenty in Christine Lagarde’s background suggests she will be much better suited to run the European Central Bank: her political nous, her communication skills, her leadership of the International Monetary Fund through turbulent financial times.

Critics, though, have focused on the former corporate lawyer and finance minister’s lack of deep academic economic training, and her dearth of experience with the technicalities of monetary policy.

But how much should the past record of a candidate be a guide for how they will handle their next job? Not as much as we might think.

The truth is that successful leadership depends on context, collaboration and character as much as qualifications. For all the efforts to codify and computerise the specifications of important jobs, the optimal chemistry of experience, aptitude, potential, and mindset remains hard to define. Throw in the imponderable future in which such leaders are bound to operate and it is no wonder that sometimes the seemingly best-qualified stumble, while the qualification-free thrive.

For one thing, even if the challenge confronting a leader looks the same as one they handled in the past, it is very rarely identical — and nor is the leader. That is one reason big companies offer their most promising executives experience across countries, cultures and operations, from finance to the front line, and why some recruiters emphasise potential as much as the formal résumé of their candidates.

Curiosity is a big predictor of potential — and of success — according to Egon Zehnder, the executive search company. It asks referees what the candidate they have backed is really curious about. “It is a question that takes people aback, so they have to think anew about that person,” Jill Ader, chairwoman, told me recently.

I think there are strong reasons to back master generalists for senior roles. Polymathic leaders offer alternative perspectives and may even be better at fostering innovation, according to one study. In his new book Range, David Epstein offers this warning against over-specialisation: “Everyone is digging deeper into their own trench and rarely standing up to look in the next trench over.”

Take this to the other extreme of ignoring specialist qualifications, however, and you are suddenly in the world of blaggers, blowhards and blackguards, who bluff their way up the leadership ladder until the Peter Principle applies, and a further rise is prohibited by their own incompetence.

The financial crisis exposed the weaknesses of large banks, such as HBOS and Royal Bank of Scotland in the UK, chaired by non-bankers. Some of the same concerns about a dearth of deep financial qualifications now nag at the leaders of fintech companies, whose promise is based in part on their boast that they will be “different” from longer established incumbents.

In a flailing search for the reasons for its current political mess, the UK has blamed the self-confident dilettantism of some Oxford university graduates, while the US bemoans the superficial attractions of stars of television reality shows. These parallel weaknesses for pure bluster over proven expertise have brought us Boris Johnson and Donald Trump, respectively.

A plausible defence of both Mr Johnson and Mr Trump is that they should be able to play to their specific strengths, while surrounding themselves with experts who can handle the technical work.

Ms Lagarde, too, will want to draw on the team of experts around her. She is wise enough to know she cannot rely on silky political skills and neglect the plumbing of monetary policy.

At the same time, history suggests she should not assume her paper credentials or wide experience will be enough to guarantee success in Frankfurt. The Bank of England’s Norman was eccentric and neurotic, and his counterpart at the Banque de France, Émile Moreau, had a “quite rudimentary and at times confused” understanding of monetary economics, whereas Benjamin Strong at the New York Federal Reserve, was a born leader, and Hjalmar Schacht of Germany’s Reichsbank “came to the job with an array of qualifications”.

Yet together this quartet of the under- and overqualified made a series of mistakes that pitched the world into the Great Depression.

Wednesday, 15 February 2017

In an age of robots, schools are teaching our children to be redundant

Illustration by Andrzej Krauze

GeorgeMonbiot in The Guardian

In the future, if you want a job, you must be as unlike a machine as possible: creative, critical and socially skilled. So why are children being taught to behave like machines?

Children learn best when teaching aligns with their natural exuberance, energy and curiosity. So why are they dragooned into rows and made to sit still while they are stuffed with facts?

We succeed in adulthood through collaboration. So why is collaboration in tests and exams called cheating?

Governments claim to want to reduce the number of children being excluded from school. So why are their curriculums and tests so narrow that they alienate any child whose mind does not work in a particular way?

The best teachers use their character, creativity and inspiration to trigger children’s instinct to learn. So why are character, creativity and inspiration suppressed by a stifling regime of micromanagement?

There is, as Graham Brown-Martin explains in his book Learning {Re}imagined, a common reason for these perversities. Our schools were designed to produce the workforce required by 19th-century factories. The desired product was workers who would sit silently at their benches all day, behaving identically, to produce identical products, submitting to punishment if they failed to achieve the requisite standards. Collaboration and critical thinking were just what the factory owners wished to discourage.

As far as relevance and utility are concerned, we might as well train children to operate a spinning jenny. Our schools teach skills that are not only redundant but counter-productive. Our children suffer this life-defying, dehumanising system for nothing.

At present we are stuck with the social engineering of an industrial workforce in a post-industrial era

The less relevant the system becomes, the harder the rules must be enforced, and the greater the stress they inflict. One school’s current advertisement in the Times Educational Supplement asks: “Do you like order and discipline? Do you believe in children being obedient every time? … If you do, then the role of detention director could be for you.” Yes, many schools have discipline problems. But is it surprising when children, bursting with energy and excitement, are confined to the spot like battery chickens?

Teachers are now leaving the profession in droves, their training wasted and their careers destroyed by overwork and a spirit-crushing regime of standardisation, testing and top-down control. The less autonomy they are granted, the more they are blamed for the failures of the system. A major recruitment crisis beckons, especially in crucial subjects such as physics and design and technology. This is what governments call efficiency.

Any attempt to change the system, to equip children for the likely demands of the 21st century, rather than those of the 19th, is demonised by governments and newspapers as “social engineering”. Well, of course it is. All teaching is social engineering. At present we are stuck with the social engineering of an industrial workforce in a post-industrial era. Under Donald Trump’s education secretary, Betsy DeVos, and a nostalgic government in Britain, it’s likely only to become worse.

GeorgeMonbiot in The Guardian

In the future, if you want a job, you must be as unlike a machine as possible: creative, critical and socially skilled. So why are children being taught to behave like machines?

Children learn best when teaching aligns with their natural exuberance, energy and curiosity. So why are they dragooned into rows and made to sit still while they are stuffed with facts?

We succeed in adulthood through collaboration. So why is collaboration in tests and exams called cheating?

Governments claim to want to reduce the number of children being excluded from school. So why are their curriculums and tests so narrow that they alienate any child whose mind does not work in a particular way?

The best teachers use their character, creativity and inspiration to trigger children’s instinct to learn. So why are character, creativity and inspiration suppressed by a stifling regime of micromanagement?

There is, as Graham Brown-Martin explains in his book Learning {Re}imagined, a common reason for these perversities. Our schools were designed to produce the workforce required by 19th-century factories. The desired product was workers who would sit silently at their benches all day, behaving identically, to produce identical products, submitting to punishment if they failed to achieve the requisite standards. Collaboration and critical thinking were just what the factory owners wished to discourage.

As far as relevance and utility are concerned, we might as well train children to operate a spinning jenny. Our schools teach skills that are not only redundant but counter-productive. Our children suffer this life-defying, dehumanising system for nothing.

At present we are stuck with the social engineering of an industrial workforce in a post-industrial era

The less relevant the system becomes, the harder the rules must be enforced, and the greater the stress they inflict. One school’s current advertisement in the Times Educational Supplement asks: “Do you like order and discipline? Do you believe in children being obedient every time? … If you do, then the role of detention director could be for you.” Yes, many schools have discipline problems. But is it surprising when children, bursting with energy and excitement, are confined to the spot like battery chickens?

Teachers are now leaving the profession in droves, their training wasted and their careers destroyed by overwork and a spirit-crushing regime of standardisation, testing and top-down control. The less autonomy they are granted, the more they are blamed for the failures of the system. A major recruitment crisis beckons, especially in crucial subjects such as physics and design and technology. This is what governments call efficiency.

Any attempt to change the system, to equip children for the likely demands of the 21st century, rather than those of the 19th, is demonised by governments and newspapers as “social engineering”. Well, of course it is. All teaching is social engineering. At present we are stuck with the social engineering of an industrial workforce in a post-industrial era. Under Donald Trump’s education secretary, Betsy DeVos, and a nostalgic government in Britain, it’s likely only to become worse.

When they are allowed to apply their natural creativity and curiosity, children love learning. They learn to walk, to talk, to eat and to play spontaneously, by watching and experimenting. Then they get to school, and we suppress this instinct by sitting them down, force-feeding them with inert facts and testing the life out of them.

There is no single system for teaching children well, but the best ones have this in common: they open up rich worlds that children can explore in their own ways, developing their interests with help rather than indoctrination. For example, the Essa academy in Bolton gives every pupil an iPad, on which they create projects, share material with their teachers and each other, and can contact their teachers with questions about their homework. By reducing their routine tasks, this system enables teachers to give the children individual help.

Other schools have gone in the opposite direction, taking children outdoors and using the natural world to engage their interests and develop their mental and physical capacities (the Forest School movement promotes this method). But it’s not a matter of high-tech or low-tech; the point is that the world a child enters is rich and diverse enough to ignite their curiosity, and allow them to discover a way of learning that best reflects their character and skills.

There are plenty of teaching programmes designed to work with children, not against them. For example, the Mantle of the Expert encourages them to form teams of inquiry, solving an imaginary task – such as running a container port, excavating a tomb or rescuing people from a disaster – that cuts across traditional subject boundaries. A similar approach, called Quest to Learn, is based on the way children teach themselves to play games. To solve the complex tasks they’re given, they need to acquire plenty of information and skills. They do it with the excitement and tenacity of gamers.

No grammar schools, lots of play: the secrets of Europe’s top education system

The Reggio Emilia approach, developed in Italy, allows children to develop their own curriculum, based on what interests them most, opening up the subjects they encounter along the way with the help of their teachers. Ashoka Changemaker schools treat empathy as “a foundational skill on a par with reading and math”, and use it to develop the kind of open, fluid collaboration that, they believe, will be the 21st century’s key skill.

The first multi-racial school in South Africa, Woodmead, developed a fully democratic method of teaching, whose rules and discipline were overseen by a student council. Its integrated studies programme, like the new system in Finland, junked traditional subjects in favour of the students’ explorations of themes, such as gold, or relationships, or the ocean. Among its alumni are some of South Africa’s foremost thinkers, politicians and businesspeople.

In countries such as Britain and the United States, such programmes succeed despite the system, not because of it. Had these governments set out to ensure that children find learning difficult and painful, they could not have done a better job. Yes, let’s have some social engineering. Let’s engineer our children out of the factory and into the real world.

Wednesday, 6 February 2013

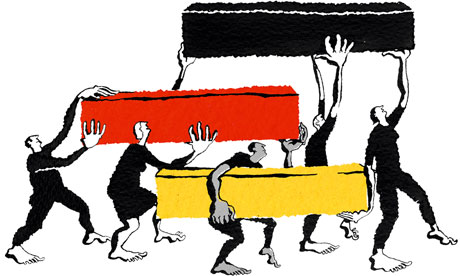

Understanding Germany and its Mittelstand ethos

Germany is right: there is no right to profit, but the right to work is essential

The strength of Germany lies in its medium-sized manufacturing firms, whose ethos includes being socially useful

'The objective of

every German business leader is to earn trust – from employees,

customers, suppliers and society as a whole.' illustration by Belle

Mellor

People talk too much about the economy and not enough about

jobs. When economists, academics and bankers are allowed to lead the

debate, the essential human element goes missing. This is neither

healthy nor practical.

Unemployment should be our prime concern. Spain, with youth joblessness close to 50%, is in the gravest crisis, but there is hardly a government on the planet that is not wondering what it can do to guide school-leavers into work, exploit the skills of older workers, and avoid the apathy and alienation of the jobless, which undermines not just the economy but also the social fabric.

There may be no definitive answer but, over the past half-century, Germany has come closest to finding it. Its postwar economic miracle was impressive, but its more recent ability to ride out recessions and absorb the costs of reunification is, perhaps, even more remarkable. Germany was not immune to the economic crisis of 2008-9, but the jobless rate rose more slowly than elsewhere in Europe. Although in recent months it has edged up towards 6.9%, it remains well below the euro area's 11.7% average. Germany's resilience springs from the strength of its medium-sized, often family-owned manufacturing companies, collectively known as the Mittelstand, which account for 60% of the workforce and 52% of Germany's GDP. So what can we learn from the Germans?

The enduring success of the Mittelstand has been well documented but rarely emulated. The standard excuse is that it is rooted in German history and culture and therefore unexportable. At a time when so much business is conducted on a global scale, via globally accessible media, this excuse is wearing thin.

Let me highlight some of the features unique to the Mittelstand model that I believe everyone should learn from – and imitate if they can. The first is what we might call the Mittelstand ethos – that business is a constructive enterprise that aims to be socially useful. Making a profit is not an end in itself: job creation, client satisfaction and product excellence are just as fundamental. Taking on debt is treated with suspicion. The objective of every business leader is to earn trust – from employees, customers, suppliers and society as a whole. This ethos chimes with the values of prudence and responsibility with which every schoolteacher hopes to imbue their pupils. Consequently, about half of all German high-school students move on to train in a trade. Business and education are natural bedfellows.

The second essential feature of the Mittelstand model is the collaborative spirit that generally exists between employer and employees. This can be dated back to the welfare state that Chancellor Otto von Bismarck established in the late 19th century to head off what he saw as the menace of socialism. Its modern-day equivalent is the system of works councils, which ensures that employees' interests are safeguarded, whether or not they belong to a trade union. German workers expect their employers to keep training them, enhancing their skills. In the post-reunification recession, it seemed only natural to German workers to offer flexibility on wages and hours in return for greater job security. More recently the government protected jobs by subsidising companies that cut hours rather than staff.

A third feature of the Mittelstand model is the determination of German companies to build for the long term. To this end, they tend to keep core functions such as engineering and project management in-house, while outsourcing production whenever this proves more efficient. Mittelstand companies are overwhelmingly privately owned, and thus largely free of pressure to provide shareholder returns. This makes them readier to innovate, and invest a larger proportion of their revenues in R&D. There are Mittelstand companies that file more patents in a year than do some entire European countries. It is one of the underlying reasons for their exporting success, even when their goods seem expensive.

Finally, German companies work closely with their suppliers. This has proved especially valuable in developing Sino-German trade. Unlike most of their international competitors, they are happy to take suppliers' representatives on trade missions. The result is that they can guarantee swift and sure supplies of components and other products. Chinese customers are not the only ones willing to pay extra for this kind of service excellence.

Of course, there are other factors that lie behind the success of the Mittelstand and of the German economy as a whole. Both the economy and political system are highly decentralised, with the result that local banks, businesses, entrepreneurs and politicians know and understand each other, making everyday co-operation easier – while, at the national level, Germany's leaders rarely miss an opportunity to promote their country's industry abroad.

Nonetheless, there is much that non-Germans could learn from. To close the gap between education and business, companies should take a greater interest in their local schools and colleges. If you haven't got spare cash for sponsoring gyms or computer equipment, go and talk to sixth-formers or degree students about what you do. Find out what graduates aspire to. It will help you to work out how to attract the next generation.

If you want to get more out of your employees and suppliers, consult them; invite them into your confidence. Don't complain: "We're not like the Germans. It won't work here." Think of a different way. Try harder.

The same applies to governments. Let me mention one simple legislative option. In German law, the owner of a family business who passes it on to the next generation can avoid paying inheritance tax if, during their tenure, they have increased employment and thereby benefited the economy. What better signal could a government give than by favouring those who create employment?

There is no question in my mind about which is the single most important feature of the Mittelstand model – its underlying ethos, which is based not on dry economic theory, but on everyday, practical humanity. The notion that business should be socially useful may have sprung from Germany's postwar conscience, but it has resonance now, when so many of our citizens are still suffering from the aftermath of the credit crunch and the failures of leadership it exposed.

There is no right to make a profit, and profit has no intrinsic value. But there is a right to work, and it is fundamental to human dignity. Without an opportunity to contribute with our hands or brains, we have no stake in society and our governments lack true legitimacy. There can be no more urgent challenge for our leaders. The title of the next G8 summit should be a four-letter word that everyone understands – jobs.

Unemployment should be our prime concern. Spain, with youth joblessness close to 50%, is in the gravest crisis, but there is hardly a government on the planet that is not wondering what it can do to guide school-leavers into work, exploit the skills of older workers, and avoid the apathy and alienation of the jobless, which undermines not just the economy but also the social fabric.

There may be no definitive answer but, over the past half-century, Germany has come closest to finding it. Its postwar economic miracle was impressive, but its more recent ability to ride out recessions and absorb the costs of reunification is, perhaps, even more remarkable. Germany was not immune to the economic crisis of 2008-9, but the jobless rate rose more slowly than elsewhere in Europe. Although in recent months it has edged up towards 6.9%, it remains well below the euro area's 11.7% average. Germany's resilience springs from the strength of its medium-sized, often family-owned manufacturing companies, collectively known as the Mittelstand, which account for 60% of the workforce and 52% of Germany's GDP. So what can we learn from the Germans?

The enduring success of the Mittelstand has been well documented but rarely emulated. The standard excuse is that it is rooted in German history and culture and therefore unexportable. At a time when so much business is conducted on a global scale, via globally accessible media, this excuse is wearing thin.

Let me highlight some of the features unique to the Mittelstand model that I believe everyone should learn from – and imitate if they can. The first is what we might call the Mittelstand ethos – that business is a constructive enterprise that aims to be socially useful. Making a profit is not an end in itself: job creation, client satisfaction and product excellence are just as fundamental. Taking on debt is treated with suspicion. The objective of every business leader is to earn trust – from employees, customers, suppliers and society as a whole. This ethos chimes with the values of prudence and responsibility with which every schoolteacher hopes to imbue their pupils. Consequently, about half of all German high-school students move on to train in a trade. Business and education are natural bedfellows.

The second essential feature of the Mittelstand model is the collaborative spirit that generally exists between employer and employees. This can be dated back to the welfare state that Chancellor Otto von Bismarck established in the late 19th century to head off what he saw as the menace of socialism. Its modern-day equivalent is the system of works councils, which ensures that employees' interests are safeguarded, whether or not they belong to a trade union. German workers expect their employers to keep training them, enhancing their skills. In the post-reunification recession, it seemed only natural to German workers to offer flexibility on wages and hours in return for greater job security. More recently the government protected jobs by subsidising companies that cut hours rather than staff.

A third feature of the Mittelstand model is the determination of German companies to build for the long term. To this end, they tend to keep core functions such as engineering and project management in-house, while outsourcing production whenever this proves more efficient. Mittelstand companies are overwhelmingly privately owned, and thus largely free of pressure to provide shareholder returns. This makes them readier to innovate, and invest a larger proportion of their revenues in R&D. There are Mittelstand companies that file more patents in a year than do some entire European countries. It is one of the underlying reasons for their exporting success, even when their goods seem expensive.

Finally, German companies work closely with their suppliers. This has proved especially valuable in developing Sino-German trade. Unlike most of their international competitors, they are happy to take suppliers' representatives on trade missions. The result is that they can guarantee swift and sure supplies of components and other products. Chinese customers are not the only ones willing to pay extra for this kind of service excellence.

Of course, there are other factors that lie behind the success of the Mittelstand and of the German economy as a whole. Both the economy and political system are highly decentralised, with the result that local banks, businesses, entrepreneurs and politicians know and understand each other, making everyday co-operation easier – while, at the national level, Germany's leaders rarely miss an opportunity to promote their country's industry abroad.

Nonetheless, there is much that non-Germans could learn from. To close the gap between education and business, companies should take a greater interest in their local schools and colleges. If you haven't got spare cash for sponsoring gyms or computer equipment, go and talk to sixth-formers or degree students about what you do. Find out what graduates aspire to. It will help you to work out how to attract the next generation.

If you want to get more out of your employees and suppliers, consult them; invite them into your confidence. Don't complain: "We're not like the Germans. It won't work here." Think of a different way. Try harder.

The same applies to governments. Let me mention one simple legislative option. In German law, the owner of a family business who passes it on to the next generation can avoid paying inheritance tax if, during their tenure, they have increased employment and thereby benefited the economy. What better signal could a government give than by favouring those who create employment?

There is no question in my mind about which is the single most important feature of the Mittelstand model – its underlying ethos, which is based not on dry economic theory, but on everyday, practical humanity. The notion that business should be socially useful may have sprung from Germany's postwar conscience, but it has resonance now, when so many of our citizens are still suffering from the aftermath of the credit crunch and the failures of leadership it exposed.

There is no right to make a profit, and profit has no intrinsic value. But there is a right to work, and it is fundamental to human dignity. Without an opportunity to contribute with our hands or brains, we have no stake in society and our governments lack true legitimacy. There can be no more urgent challenge for our leaders. The title of the next G8 summit should be a four-letter word that everyone understands – jobs.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)