Illustration by Andrzej Krauze

GeorgeMonbiot in The Guardian

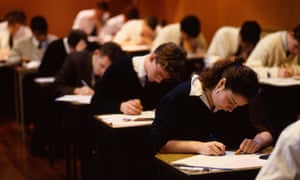

In the future, if you want a job, you must be as unlike a machine as possible: creative, critical and socially skilled. So why are children being taught to behave like machines?

Children learn best when teaching aligns with their natural exuberance, energy and curiosity. So why are they dragooned into rows and made to sit still while they are stuffed with facts?

We succeed in adulthood through collaboration. So why is collaboration in tests and exams called cheating?

Governments claim to want to reduce the number of children being excluded from school. So why are their curriculums and tests so narrow that they alienate any child whose mind does not work in a particular way?

The best teachers use their character, creativity and inspiration to trigger children’s instinct to learn. So why are character, creativity and inspiration suppressed by a stifling regime of micromanagement?

There is, as Graham Brown-Martin explains in his book Learning {Re}imagined, a common reason for these perversities. Our schools were designed to produce the workforce required by 19th-century factories. The desired product was workers who would sit silently at their benches all day, behaving identically, to produce identical products, submitting to punishment if they failed to achieve the requisite standards. Collaboration and critical thinking were just what the factory owners wished to discourage.

As far as relevance and utility are concerned, we might as well train children to operate a spinning jenny. Our schools teach skills that are not only redundant but counter-productive. Our children suffer this life-defying, dehumanising system for nothing.

At present we are stuck with the social engineering of an industrial workforce in a post-industrial era

The less relevant the system becomes, the harder the rules must be enforced, and the greater the stress they inflict. One school’s current advertisement in the Times Educational Supplement asks: “Do you like order and discipline? Do you believe in children being obedient every time? … If you do, then the role of detention director could be for you.” Yes, many schools have discipline problems. But is it surprising when children, bursting with energy and excitement, are confined to the spot like battery chickens?

Teachers are now leaving the profession in droves, their training wasted and their careers destroyed by overwork and a spirit-crushing regime of standardisation, testing and top-down control. The less autonomy they are granted, the more they are blamed for the failures of the system. A major recruitment crisis beckons, especially in crucial subjects such as physics and design and technology. This is what governments call efficiency.

Any attempt to change the system, to equip children for the likely demands of the 21st century, rather than those of the 19th, is demonised by governments and newspapers as “social engineering”. Well, of course it is. All teaching is social engineering. At present we are stuck with the social engineering of an industrial workforce in a post-industrial era. Under Donald Trump’s education secretary, Betsy DeVos, and a nostalgic government in Britain, it’s likely only to become worse.

GeorgeMonbiot in The Guardian

In the future, if you want a job, you must be as unlike a machine as possible: creative, critical and socially skilled. So why are children being taught to behave like machines?

Children learn best when teaching aligns with their natural exuberance, energy and curiosity. So why are they dragooned into rows and made to sit still while they are stuffed with facts?

We succeed in adulthood through collaboration. So why is collaboration in tests and exams called cheating?

Governments claim to want to reduce the number of children being excluded from school. So why are their curriculums and tests so narrow that they alienate any child whose mind does not work in a particular way?

The best teachers use their character, creativity and inspiration to trigger children’s instinct to learn. So why are character, creativity and inspiration suppressed by a stifling regime of micromanagement?

There is, as Graham Brown-Martin explains in his book Learning {Re}imagined, a common reason for these perversities. Our schools were designed to produce the workforce required by 19th-century factories. The desired product was workers who would sit silently at their benches all day, behaving identically, to produce identical products, submitting to punishment if they failed to achieve the requisite standards. Collaboration and critical thinking were just what the factory owners wished to discourage.

As far as relevance and utility are concerned, we might as well train children to operate a spinning jenny. Our schools teach skills that are not only redundant but counter-productive. Our children suffer this life-defying, dehumanising system for nothing.

At present we are stuck with the social engineering of an industrial workforce in a post-industrial era

The less relevant the system becomes, the harder the rules must be enforced, and the greater the stress they inflict. One school’s current advertisement in the Times Educational Supplement asks: “Do you like order and discipline? Do you believe in children being obedient every time? … If you do, then the role of detention director could be for you.” Yes, many schools have discipline problems. But is it surprising when children, bursting with energy and excitement, are confined to the spot like battery chickens?

Teachers are now leaving the profession in droves, their training wasted and their careers destroyed by overwork and a spirit-crushing regime of standardisation, testing and top-down control. The less autonomy they are granted, the more they are blamed for the failures of the system. A major recruitment crisis beckons, especially in crucial subjects such as physics and design and technology. This is what governments call efficiency.

Any attempt to change the system, to equip children for the likely demands of the 21st century, rather than those of the 19th, is demonised by governments and newspapers as “social engineering”. Well, of course it is. All teaching is social engineering. At present we are stuck with the social engineering of an industrial workforce in a post-industrial era. Under Donald Trump’s education secretary, Betsy DeVos, and a nostalgic government in Britain, it’s likely only to become worse.

When they are allowed to apply their natural creativity and curiosity, children love learning. They learn to walk, to talk, to eat and to play spontaneously, by watching and experimenting. Then they get to school, and we suppress this instinct by sitting them down, force-feeding them with inert facts and testing the life out of them.

There is no single system for teaching children well, but the best ones have this in common: they open up rich worlds that children can explore in their own ways, developing their interests with help rather than indoctrination. For example, the Essa academy in Bolton gives every pupil an iPad, on which they create projects, share material with their teachers and each other, and can contact their teachers with questions about their homework. By reducing their routine tasks, this system enables teachers to give the children individual help.

Other schools have gone in the opposite direction, taking children outdoors and using the natural world to engage their interests and develop their mental and physical capacities (the Forest School movement promotes this method). But it’s not a matter of high-tech or low-tech; the point is that the world a child enters is rich and diverse enough to ignite their curiosity, and allow them to discover a way of learning that best reflects their character and skills.

There are plenty of teaching programmes designed to work with children, not against them. For example, the Mantle of the Expert encourages them to form teams of inquiry, solving an imaginary task – such as running a container port, excavating a tomb or rescuing people from a disaster – that cuts across traditional subject boundaries. A similar approach, called Quest to Learn, is based on the way children teach themselves to play games. To solve the complex tasks they’re given, they need to acquire plenty of information and skills. They do it with the excitement and tenacity of gamers.

No grammar schools, lots of play: the secrets of Europe’s top education system

The Reggio Emilia approach, developed in Italy, allows children to develop their own curriculum, based on what interests them most, opening up the subjects they encounter along the way with the help of their teachers. Ashoka Changemaker schools treat empathy as “a foundational skill on a par with reading and math”, and use it to develop the kind of open, fluid collaboration that, they believe, will be the 21st century’s key skill.

The first multi-racial school in South Africa, Woodmead, developed a fully democratic method of teaching, whose rules and discipline were overseen by a student council. Its integrated studies programme, like the new system in Finland, junked traditional subjects in favour of the students’ explorations of themes, such as gold, or relationships, or the ocean. Among its alumni are some of South Africa’s foremost thinkers, politicians and businesspeople.

In countries such as Britain and the United States, such programmes succeed despite the system, not because of it. Had these governments set out to ensure that children find learning difficult and painful, they could not have done a better job. Yes, let’s have some social engineering. Let’s engineer our children out of the factory and into the real world.