'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label exploitation. Show all posts

Showing posts with label exploitation. Show all posts

Wednesday, 17 July 2024

Saturday, 7 January 2023

Tuesday, 22 November 2022

Hypocrisy's Penalty Corner

Jawed Naqvi in The Dawn

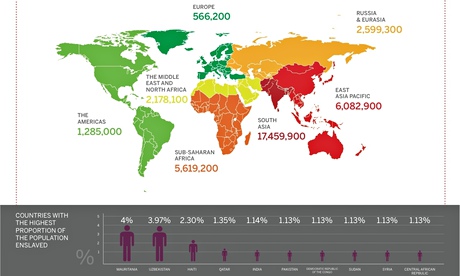

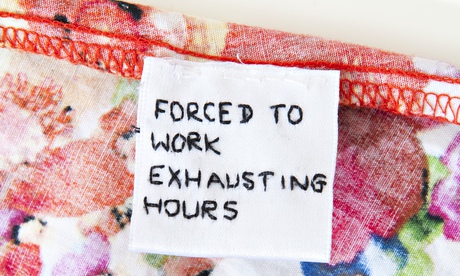

THERE’S been severe criticism, primarily in the Western media, of the gross exploitation of migrant workers in Qatar’s bid to host football’s World Cup that began in Doha last week. There’s more than a grain of truth in the accusation, and there’s dollops of hypocrisy about it.

FIFA President Gianni Infantino brought it out nicely by calling out the Western media’s double standards in what is tantamount to shedding crocodile tears for the exploited workers.

The CNN, unsurprisingly, slammed Infantino’s anger, and quoted human rights groups as describing his comments as “crass” and an “insult” to migrant workers. Why is Infantino convinced that the Western media wallows in its own arrogance?

It is nobody’s secret that migrant workers in the Gulf are paid a pittance, which becomes more deplorable when compared to the enormous riches they help produce. As is evident, the workers’ exploitation is not specific to Qatar’s hosting of a football tournament, but a deeper malaise in which Western greed mocks its moral sermons.

As their earnings with hard labour abroad fetch them more than what they would get at home, the workers become unwitting partners in their own abuse. This has been the unwritten law around the generation of wealth in oil-rich Gulf countries, though their rulers are not alone in the exploitative venture.

Western colluders, nearly all of them champions of human rights, have used the oil extracted with cheap labour that plies Gulf economies, to control the world order. The West and the Gulf states have both benefited directly from dirt cheap workforce sourced from countries like India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Bangladesh and the far away Philippines.

Making it considerably worse is the sullen cutthroat competition that has prevailed for decades between workers of different countries, thereby undercutting each other’s bargaining power. The bruising competition is not unknown to their respective governments that benefit enormously from the remittances from an exploited workforce. The disregard for work conditions is not only related to the Gulf workers, of course, but also migrant labour at home. In the case of India, we witnessed the criminal apathy they experienced in the Covid-19 emergency.

Asian women workers in the Gulf face quantifiably worse conditions. An added challenge they face is of sexual exploitation. Cheap labour imported from South Asia, therefore, answers to the overused though still germane term — Western imperialism. Infantino was spot on. Pity the self-absorbed Western press booed him down.

Sham outrage over a Gulf country hosting the World Cup is just one aspect of hypocrisy. A larger problem remains rooted in an undiscussed bias.

Moscow and Beijing in particular have been the Western media’s leading quarries from time immemorial. The boycott of the Moscow Olympics over the USSR’s invasion of Afghanistan was dressed up as a moral proposition, which it might have been but for the forked tongue at play. That numerous Olympic contests went ahead undeterred in Western cities despite their illegal wars or support for dictators everywhere was never called out. What the West did with China, however, bordered on distilled criminality.

I was visiting Beijing in September 1993 with prime minister Narasimha Rao’s media team. The streets were lined with colourful buntings and slogans, which one mistook for a grand welcome for the visiting Indian leader. As it turned out the enthusiasm was all about Beijing’s bid to host the 2000 Olympics. It was fortunate Rao arrived on Sept 6 and could sign with Li Peng a landmark agreement for “peace and tranquility” on the Sino-Indian borders. Barely two week later, China would collapse into collective depression after Sydney snatched the 2000 Olympics from Beijing’s clasp. Western perfidy was at work again.

As it happened, other than Sydney and Beijing three other cities were also in the running — Manchester, Berlin and Istanbul — but, as The New York Times noted: “No country placed its prestige more on the line than China.” When the count began, China led the field with a clear margin over Sydney. Then the familiar mischief came into play.

Beijing led after each of the first three rounds, but was unable to win the required majority of the 89 voting members. One voter did not cast a ballot in the final two rounds. After the third round, in which Manchester won 11 votes, Beijing still led Sydney by 40 to 37 ballots. “But, confirming predictions that many Western delegates were eager to block Beijing’s bid, eight of Manchester’s votes went to Sydney and only three to the Chinese capital,” NYT reported. Human rights was cited as the cause. Hypocritically, that concern disappeared out of sight and Beijing hosted a grand Summer Olympics in 2008.

Football is a mesmerising game to watch. Its movements are comparable to musical notes of a riveting symphony. Above all, it’s a sport that cannot be easily fudged with. But its backstage in our era of the lucre stinks of pervasive corruption.

Anger in Beijing burst into the open when it was revealed in January 1999 that Australia’s Olympic Committee president John Coates promised two International Olympic Committee members $35,000 each for their national Olympic committees the night before the vote, which gave the games to Sydney by 45 votes to 43.

The Daily Mail described the “usual equanimity” with which Juan Antonio Samaranch, the then Spanish IOC president, tried to diminish the scam. The allegations against nine of the 10 IOC members accused of graft “have scant foundation and the remaining one has hardly done anything wrong”.

“In a speech to his countrymen,” recalled the Mail, “he blamed the press for ‘overreacting’ to the underhand tactics, including the hire of prostitutes, employed by Salt Lake City to host the next Winter Olympics.” Samaranch sidestepped any reference to the tactics employed by Sydney to stage the Millennium Summer Games.

This reality should never be obscured by other outrages, including the abominable working conditions of Asian workers in Qatar.

THERE’S been severe criticism, primarily in the Western media, of the gross exploitation of migrant workers in Qatar’s bid to host football’s World Cup that began in Doha last week. There’s more than a grain of truth in the accusation, and there’s dollops of hypocrisy about it.

FIFA President Gianni Infantino brought it out nicely by calling out the Western media’s double standards in what is tantamount to shedding crocodile tears for the exploited workers.

The CNN, unsurprisingly, slammed Infantino’s anger, and quoted human rights groups as describing his comments as “crass” and an “insult” to migrant workers. Why is Infantino convinced that the Western media wallows in its own arrogance?

It is nobody’s secret that migrant workers in the Gulf are paid a pittance, which becomes more deplorable when compared to the enormous riches they help produce. As is evident, the workers’ exploitation is not specific to Qatar’s hosting of a football tournament, but a deeper malaise in which Western greed mocks its moral sermons.

As their earnings with hard labour abroad fetch them more than what they would get at home, the workers become unwitting partners in their own abuse. This has been the unwritten law around the generation of wealth in oil-rich Gulf countries, though their rulers are not alone in the exploitative venture.

Western colluders, nearly all of them champions of human rights, have used the oil extracted with cheap labour that plies Gulf economies, to control the world order. The West and the Gulf states have both benefited directly from dirt cheap workforce sourced from countries like India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Bangladesh and the far away Philippines.

Making it considerably worse is the sullen cutthroat competition that has prevailed for decades between workers of different countries, thereby undercutting each other’s bargaining power. The bruising competition is not unknown to their respective governments that benefit enormously from the remittances from an exploited workforce. The disregard for work conditions is not only related to the Gulf workers, of course, but also migrant labour at home. In the case of India, we witnessed the criminal apathy they experienced in the Covid-19 emergency.

Asian women workers in the Gulf face quantifiably worse conditions. An added challenge they face is of sexual exploitation. Cheap labour imported from South Asia, therefore, answers to the overused though still germane term — Western imperialism. Infantino was spot on. Pity the self-absorbed Western press booed him down.

Sham outrage over a Gulf country hosting the World Cup is just one aspect of hypocrisy. A larger problem remains rooted in an undiscussed bias.

Moscow and Beijing in particular have been the Western media’s leading quarries from time immemorial. The boycott of the Moscow Olympics over the USSR’s invasion of Afghanistan was dressed up as a moral proposition, which it might have been but for the forked tongue at play. That numerous Olympic contests went ahead undeterred in Western cities despite their illegal wars or support for dictators everywhere was never called out. What the West did with China, however, bordered on distilled criminality.

I was visiting Beijing in September 1993 with prime minister Narasimha Rao’s media team. The streets were lined with colourful buntings and slogans, which one mistook for a grand welcome for the visiting Indian leader. As it turned out the enthusiasm was all about Beijing’s bid to host the 2000 Olympics. It was fortunate Rao arrived on Sept 6 and could sign with Li Peng a landmark agreement for “peace and tranquility” on the Sino-Indian borders. Barely two week later, China would collapse into collective depression after Sydney snatched the 2000 Olympics from Beijing’s clasp. Western perfidy was at work again.

As it happened, other than Sydney and Beijing three other cities were also in the running — Manchester, Berlin and Istanbul — but, as The New York Times noted: “No country placed its prestige more on the line than China.” When the count began, China led the field with a clear margin over Sydney. Then the familiar mischief came into play.

Beijing led after each of the first three rounds, but was unable to win the required majority of the 89 voting members. One voter did not cast a ballot in the final two rounds. After the third round, in which Manchester won 11 votes, Beijing still led Sydney by 40 to 37 ballots. “But, confirming predictions that many Western delegates were eager to block Beijing’s bid, eight of Manchester’s votes went to Sydney and only three to the Chinese capital,” NYT reported. Human rights was cited as the cause. Hypocritically, that concern disappeared out of sight and Beijing hosted a grand Summer Olympics in 2008.

Football is a mesmerising game to watch. Its movements are comparable to musical notes of a riveting symphony. Above all, it’s a sport that cannot be easily fudged with. But its backstage in our era of the lucre stinks of pervasive corruption.

Anger in Beijing burst into the open when it was revealed in January 1999 that Australia’s Olympic Committee president John Coates promised two International Olympic Committee members $35,000 each for their national Olympic committees the night before the vote, which gave the games to Sydney by 45 votes to 43.

The Daily Mail described the “usual equanimity” with which Juan Antonio Samaranch, the then Spanish IOC president, tried to diminish the scam. The allegations against nine of the 10 IOC members accused of graft “have scant foundation and the remaining one has hardly done anything wrong”.

“In a speech to his countrymen,” recalled the Mail, “he blamed the press for ‘overreacting’ to the underhand tactics, including the hire of prostitutes, employed by Salt Lake City to host the next Winter Olympics.” Samaranch sidestepped any reference to the tactics employed by Sydney to stage the Millennium Summer Games.

This reality should never be obscured by other outrages, including the abominable working conditions of Asian workers in Qatar.

Thursday, 17 March 2022

Thursday, 30 July 2020

All marriages are arranged

Sadhguru Jaggi Vasudev in The Indian Express

Arranged marriage is a wrong terminology, because all marriages are arranged. By whom is the only question. Whether your parents or friends arranged it, or a commercial website or dating app arranged it, or you arranged it – anyway, it is an arrangement.

The idea that arranged marriage is some kind of a slavery – well that depends on whether there is exploitation. There are exploitative people everywhere. Sometimes, even your parents themselves may be exploitative – they may be doing things for their own reasons, like their prestige, their wealth, their nonsense.

Recently, someone asked me about choosing a girl for their boy. One girl is well-educated and pretty, but another girl had a wealthy father. They asked me which they should choose. So I asked a simple question, “Do you want to marry the girl or someone’s wealth?” It depends on what is your priority. If your priority is such that someone’s wealth by marriage becomes yours and that is all that matters to you, that is fine. Well, that is the kind of life you have chosen.

Arranged marriage and divorce rates

The success of something is in the result. Luxembourg, a small country which is held as one of the most economically prosperous and free societies, has a divorce rate of eighty-seven per cent. In Spain, the divorce rate is around sixty-five per cent; Russia is at fifty-one per cent; United States, forty-six per cent. India: 1.5 per cent. You decide which works best.

Well, people may say the divorce rate here is low due to the social stigma associated with divorce, but definitely how it is arranged is also an important factor. When parents are the basis of organising the marriage, the success rate is a little better because they will think more long term. You may just like the way a girl is dressed and you want to get married today. Well, tomorrow morning you could realise you don’t want to have anything to do with her! When you are twenty, due to various compulsions or peer pressure, you may take decisions which will not last a lifetime. But sometimes you really hit it off with someone and it may work out – that is another matter.

Everything is an arrangement. You may think so many things about it, but it is arranged by your emotion, your greed, or by someone. It is an arrangement. It is best that it is arranged by responsible, sensible people, by those who are most concerned about your wellbeing, who have a larger reach. You cannot find the best man or woman in the world because we do not know where they are! With the limited contacts that we have, we can arrange something that is reasonably good. That is all it is.

If a young man or young woman wants to marry, who will they marry? Their contacts are very limited. Within those ten people that they know in their life, you marry one guy or girl. Within three months you will know what it really is. But in most countries, there is a law: if you make a mistake, at least two years you must suffer before you can divorce. It is like a jail term. Well, many religions have fixed it that you cannot divorce, that it is completely wrong. But where such religions are practiced, there the divorce rate is highest. So, neither God’s diktats nor the law is able to stop the breakups.

When parents organise a marriage, their judgement may not be the best, but they generally have your best interests in mind. If you have matured beyond your parents’ judgement or prejudice, that is different – now you can make your own decisions.

Conducting your marriage responsibly

When I married I did not know my wife’s full name. I did not know her father’s name. I did not know her caste. When I told my father that I wanted to marry her, he said, “What? You don’t know her father’s name? You don’t know who they are, or what they are? How can you marry her?”

I said, “I’m only marrying her. I’m not planning to marry any of the other things that come with her. Just her. That’s it.” I was absolutely clear about her potential and what she will bring to me, and she was helplessly in love from the first moment.

Though I never took anyone’s advice in my life, there are always self-appointed advisors who said, “You’re making the biggest mistake in your life, this is going to be a disaster.”

I said, “Whatever happens, whichever way it happens, it is for me either to make it a disaster or a success.” I knew this much.

Because who you marry, how you marry, which way it was arranged or by whom it was arranged is not important. How responsibly you exist – that is all there is. How you arrange the marriage is your choice. I’m not saying this or that is the way, but whichever way you do it, please conduct it responsibly, joyfully. You need to understand to fulfil your needs, physical, psychological, emotional, social and various other needs, you are coming together. If you always remember, “To fulfil my needs, I’m with you,” then you will conduct this responsibly. Initially, you may be like that, but after some time, you think he or she needs you; then you will start acting wantonly and, of course, ugliness will start in many different ways.

This happened. A young man and a young woman got engaged. So once the ring was slid on her finger, the young woman said to him, “You can lean on me to share your pains, your struggles. Whatever sufferings you go through, you can always share them with me.”

The guy said, “Well, I don’t have any struggles or pains or problems.”

She said, “Well, we are not yet married.”

If you think you are full of pain, struggles, and problems and need someone to lean on, there will be trouble. You know, they have been saying, marriages are made in heaven, but you are cooking hell within you. If you think someone else is going to fix you then there will be trouble for you, and of course, unfortunate consequences for the other person. If you make yourself into a joyful, wonderful human being, then you will see, your work, home and marriage will all be wonderful. Everything will be wonderful because you are!

Arranged marriage is a wrong terminology, because all marriages are arranged. By whom is the only question. Whether your parents or friends arranged it, or a commercial website or dating app arranged it, or you arranged it – anyway, it is an arrangement.

The idea that arranged marriage is some kind of a slavery – well that depends on whether there is exploitation. There are exploitative people everywhere. Sometimes, even your parents themselves may be exploitative – they may be doing things for their own reasons, like their prestige, their wealth, their nonsense.

Recently, someone asked me about choosing a girl for their boy. One girl is well-educated and pretty, but another girl had a wealthy father. They asked me which they should choose. So I asked a simple question, “Do you want to marry the girl or someone’s wealth?” It depends on what is your priority. If your priority is such that someone’s wealth by marriage becomes yours and that is all that matters to you, that is fine. Well, that is the kind of life you have chosen.

Arranged marriage and divorce rates

The success of something is in the result. Luxembourg, a small country which is held as one of the most economically prosperous and free societies, has a divorce rate of eighty-seven per cent. In Spain, the divorce rate is around sixty-five per cent; Russia is at fifty-one per cent; United States, forty-six per cent. India: 1.5 per cent. You decide which works best.

Well, people may say the divorce rate here is low due to the social stigma associated with divorce, but definitely how it is arranged is also an important factor. When parents are the basis of organising the marriage, the success rate is a little better because they will think more long term. You may just like the way a girl is dressed and you want to get married today. Well, tomorrow morning you could realise you don’t want to have anything to do with her! When you are twenty, due to various compulsions or peer pressure, you may take decisions which will not last a lifetime. But sometimes you really hit it off with someone and it may work out – that is another matter.

Everything is an arrangement. You may think so many things about it, but it is arranged by your emotion, your greed, or by someone. It is an arrangement. It is best that it is arranged by responsible, sensible people, by those who are most concerned about your wellbeing, who have a larger reach. You cannot find the best man or woman in the world because we do not know where they are! With the limited contacts that we have, we can arrange something that is reasonably good. That is all it is.

If a young man or young woman wants to marry, who will they marry? Their contacts are very limited. Within those ten people that they know in their life, you marry one guy or girl. Within three months you will know what it really is. But in most countries, there is a law: if you make a mistake, at least two years you must suffer before you can divorce. It is like a jail term. Well, many religions have fixed it that you cannot divorce, that it is completely wrong. But where such religions are practiced, there the divorce rate is highest. So, neither God’s diktats nor the law is able to stop the breakups.

When parents organise a marriage, their judgement may not be the best, but they generally have your best interests in mind. If you have matured beyond your parents’ judgement or prejudice, that is different – now you can make your own decisions.

Conducting your marriage responsibly

When I married I did not know my wife’s full name. I did not know her father’s name. I did not know her caste. When I told my father that I wanted to marry her, he said, “What? You don’t know her father’s name? You don’t know who they are, or what they are? How can you marry her?”

I said, “I’m only marrying her. I’m not planning to marry any of the other things that come with her. Just her. That’s it.” I was absolutely clear about her potential and what she will bring to me, and she was helplessly in love from the first moment.

Though I never took anyone’s advice in my life, there are always self-appointed advisors who said, “You’re making the biggest mistake in your life, this is going to be a disaster.”

I said, “Whatever happens, whichever way it happens, it is for me either to make it a disaster or a success.” I knew this much.

Because who you marry, how you marry, which way it was arranged or by whom it was arranged is not important. How responsibly you exist – that is all there is. How you arrange the marriage is your choice. I’m not saying this or that is the way, but whichever way you do it, please conduct it responsibly, joyfully. You need to understand to fulfil your needs, physical, psychological, emotional, social and various other needs, you are coming together. If you always remember, “To fulfil my needs, I’m with you,” then you will conduct this responsibly. Initially, you may be like that, but after some time, you think he or she needs you; then you will start acting wantonly and, of course, ugliness will start in many different ways.

This happened. A young man and a young woman got engaged. So once the ring was slid on her finger, the young woman said to him, “You can lean on me to share your pains, your struggles. Whatever sufferings you go through, you can always share them with me.”

The guy said, “Well, I don’t have any struggles or pains or problems.”

She said, “Well, we are not yet married.”

If you think you are full of pain, struggles, and problems and need someone to lean on, there will be trouble. You know, they have been saying, marriages are made in heaven, but you are cooking hell within you. If you think someone else is going to fix you then there will be trouble for you, and of course, unfortunate consequences for the other person. If you make yourself into a joyful, wonderful human being, then you will see, your work, home and marriage will all be wonderful. Everything will be wonderful because you are!

Tuesday, 7 May 2019

Red Meat Republic - The Story of Beef

Exploitation and predatory pricing drove the transformation of the US beef industry – and created the model for modern agribusiness. By Joshua Specht in The Guardian

The meatpacking mogul Jonathan Ogden Armour could not abide socialist agitators. It was 1906, and Upton Sinclair had just published The Jungle, an explosive novel revealing the grim underside of the American meatpacking industry. Sinclair’s book told the tale of an immigrant family’s toil in Chicago’s slaughterhouses, tracing the family’s physical, financial and emotional collapse. The Jungle was not Armour’s only concern. The year before, the journalist Charles Edward Russell’s book The Greatest Trust in the World had detailed the greed and exploitation of a packing industry that came to the American dining table “three times a day … and extorts its tribute”.

In response to these attacks, Armour, head of the enormous Chicago-based meatpacking firm Armour & Co, took to the Saturday Evening Post to defend himself and his industry. Where critics saw filth, corruption and exploitation, Armour saw cleanliness, fairness and efficiency. If it were not for “the professional agitators of the country”, he claimed, the nation would be free to enjoy an abundance of delicious and affordable meat.

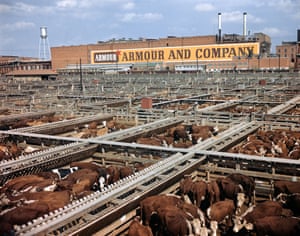

Armour and his critics could agree on this much: they lived in a world unimaginable 50 years before. In 1860, most cattle lived, died and were consumed within a few hundred miles’ radius. By 1906, an animal could be born in Texas, slaughtered in Chicago and eaten in New York. Americans rich and poor could expect to eat beef for dinner. The key aspects of modern beef production – highly centralised, meatpacker-dominated and low-cost – were all pioneered during that period.

For Armour, cheap beef and a thriving centralised meatpacking industry were the consequence of emerging technologies such as the railroad and refrigeration coupled with the business acumen of a set of honest and hard-working men like his father, Philip Danforth Armour. According to critics, however, a capitalist cabal was exploiting technological change and government corruption to bankrupt traditional butchers, sell diseased meat and impoverish the worker.

Ultimately, both views were correct. The national market for fresh beef was the culmination of a technological revolution, but it was also the result of collusion and predatory pricing. The industrial slaughterhouse was a triumph of human ingenuity as well as a site of brutal labour exploitation. Industrial beef production, with all its troubling costs and undeniable benefits, reflected seemingly contradictory realities.

Beef production would also help drive far-reaching changes in US agriculture. Fresh-fruit distribution began with the rise of the meatpackers’ refrigerator cars, which they rented to fruit and vegetable growers. Production of wheat, perhaps the US’s greatest food crop, bore the meatpackers’ mark. In order to manage animal feed costs, Armour & Co and Swift & Co invested heavily in wheat futures and controlled some of the country’s largest grain elevators. In the early 20th century, an Armour & Co promotional map announced that “the greatness of the United States is founded on agriculture”, and depicted the agricultural products of each US state, many of which moved through Armour facilities.

Beef was a paradigmatic industry for the rise of modern industrial agriculture, or agribusiness. As much as a story of science or technology, modern agriculture is a compromise between the unpredictability of nature and the rationality of capital. This was a lurching, violent process that sawmeatpackers displace the risks of blizzards, drought, disease and overproduction on to cattle ranchers. Today’s agricultural system works similarly. In poultry, processors like Perdue and Tyson use an elaborate system of contracts and required equipment and feed purchases to maximise their own profits while displacing risk on to contract farmers. This is true with crop production as well. As with 19th-century meatpacking, relatively small actors conduct the actual growing and production, while companies like Monsanto and Cargill control agricultural inputs and market access.

The transformations that remade beef production between the end of the American civil war in 1865 and the passage of the Federal Meat Inspection Act in 1906 stretched from the Great Plains to the kitchen table. Before the civil war, cattle raising was largely regional, and in most cases, the people who managed cattle out west were the same people who owned them. Then, in the 1870s and 80s, improved transport, bloody victories over the Plains Indians, and the American west’s integration into global capital markets sparked a ranching boom. Meanwhile, Chicago meatpackers pioneered centralised food processing. Using an innovative system of refrigerator cars and distribution centres, they began to distribute fresh beef nationwide. Millions of cattle were soon passing through Chicago’s slaughterhouses each year. By 1890, the Big Four meatpacking companies – Armour & Co, Swift & Co, Morris & Co and the GH Hammond Co – directly or indirectly controlled the majority of the nation’s beef and pork.

But in the 1880s, the big Chicago meatpackers faced determined opposition at every stage from slaughter to sale. Meatpackers fought with workers as they imposed a brutally exploitative labour regime. Meanwhile, attempts to transport freshly butchered beef faced opposition from railroads who found higher profits transporting live cattle east out of Chicago and to local slaughterhouses in eastern cities. Once pre-slaughtered and partially processed beef – known as “dressed beef” – reached the nation’s many cities and towns, the packers fought to displace traditional butchers and woo consumers sceptical of eating meat from an animal slaughtered a continent away.

The consequences of each of these struggles persist today. A small number of firms still control most of the country’s – and by now the world’s – beef. They draw from many comparatively small ranchers and cattle feeders, and depend on a low-paid, mostly invisible workforce. The fact that this set of relationships remains so stable, despite the public’s abstract sense that something is not quite right, is not the inevitable consequence of technological change but the direct result of the political struggles of the late 19th century.

In the slaughterhouse, someone was always willing to take your place. This could not have been far from the mind of 14-year-old Vincentz Rutkowski as he stooped, knife in hand, in a Swift & Co facility in summer 1892. For up to 10 hours each day, Vincentz trimmed tallow from cattle paunches. The job required strong workers who were low to the ground, making it ideal for boys like Rutkowski, who had the beginnings of the strength but not the size of grown men. For the first two weeks of his employment, Rutkowski shared his job with two other boys. As they became more skilled, one of the boys was fired. Another few weeks later, the other was also removed, and Rutkowski was expected to do the work of three people.

The morning that final co-worker left, on 30 June, Rutkowski fell behind the disassembly line’s frenetic pace. After just three hours of working alone, the boy failed to dodge a carcass swinging toward him. It struck his knife hand, driving the tool into his left arm near the elbow. The knife cut muscle and tendon, leaving Rutkowski with lifelong injuries.

The labour regime that led to Rutkowski’s injury was integral to large-scale meatpacking. A packinghouse was a masterpiece of technological and organisational achievement, but that was not enough to slaughter millions of cattle annually. Packing plants needed cheap, reliable and desperate labour. They found it via the combination of mass immigration and a legal regime that empowered management, checked the nascent power of unions and provided limited liability for worker injury. The Big Four’s output depended on worker quantity over worker quality.

Meatpacking lines, pioneered in the 1860s in Cincinnati’s pork packinghouses, were the first modern production lines. The innovation was that they kept products moving continuously, eliminating downtime and requiring workers to synchronise their movements to keep pace. This idea was enormously influential. In his memoirs, Henry Ford explained that his idea for continuous motion assembly “came in a general way from the overhead trolley that the Chicago packers use in dressing beef”.

A Swift and Company meatpacking house in Chicago, circa 1906. Photograph: Granger Historical Picture Archive/Alamy

Packing plants relied on a brilliant intensification of the division of labour. This division increased productivity because it simplified slaughter tasks. Workers could then be trained quickly, and because the tasks were also synchronised, everyone had to match the pace of the fastest worker.

When cattle first entered one of these slaughterhouses, they encountered an armed man walking toward them on an overhead plank. Whether by a hammer swing to the skull or a spear thrust to the animal’s spinal column, the (usually achieved) goal was to kill with a single blow. Assistants chained the animal’s legs and dragged the carcass from the room. The carcass was hoisted into the air and brought from station to station along an overhead rail.

Next, a worker cut the animal’s throat and drained and collected its blood while another group began skinning the carcass. Even this relatively simple process was subdivided throughout the period. Initially the work of a pair, nine different workers handled skinning by 1904. Once the carcass was stripped, gutted and drained of blood, it went into another room, where highly trained butchers cut the carcass into quarters. These quarters were stored in giant refrigerated rooms to await distribution.

But profitability was not just about what happened inside slaughterhouses. It also depended on what was outside: throngs of men and women hoping to find a day’s or a week’s employment. An abundant labour supply meant the packers could easily replace anyone who balked at paltry salaries or, worse yet, tried to unionise. Similarly, productivity increases heightened the risk of worker injury, and therefore were only effective if people could be easily replaced. Fortunately for the packers, late 19th-century Chicago was full of people desperate for work.

Seasonal fluctuations and the vagaries of the nation’s cattle markets further conspired to marginalise slaughterhouse labour. Though refrigeration helped the meatpackers “defeat the seasons” and secure year-round shipping, packing remained seasonal. Packers had to reckon with cattle’s reproductive cycles, and distribution in hot weather was more expensive. The number of animals processed varied day to day and month to month. For packinghouse workers, the effect was a world in which an individual day’s labour might pay relatively well but busy days were punctuated with long stretches of little or no work. The least skilled workers might only find a few weeks or months of employment at a time.

The work was so competitive and the workers so desperate that, even when they had jobs, they often had to wait, without pay, if there were no animals to slaughter. Workers would be fired if they did not show up at a specified time before 9am, but then might wait, unpaid, until 10am or 11am for a shipment. If the delivery was very late, work might continue until late into the night.

Though the division of labour and throngs of unemployed people were crucial to operating the Big Four’s disassembly lines, these factors were not sufficient to maintain a relentless production pace. This required intervention directly on the line. Fortunately for the packers, they could exploit a core aspect of continuous-motion processing: if one person went faster, everyone had to go faster. The meatpackers used pace-setters to force other workers to increase their speed. The packers would pay this select group – roughly one in 10 workers – higher wages and offer secure positions that they only kept if they maintained a rapid pace, forcing the rest of the line to keep up. These pace-setters were resented by their co-workers, and were a vital management tool.

Close supervision of foremen was equally important. Management kept statistics on production-line output, and overseers who slipped in production could lose their jobs. This encouraged foremen to use tactics that management did not want to explicitly support. According to one retired foreman, he was “always trying to cut down wages in every possible way … some of [the foremen] got a commission on all expenses they could save below a certain point”. Though union officials vilified foremen, their jobs were only marginally less tenuous than those of their underlings.

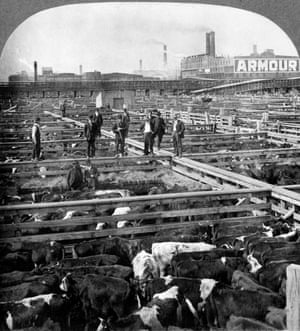

Union Stock Yard in Chicago in 1909. Photograph: Science History Images/Alamy

The effectiveness of de-skilling on the disassembly line rested on an increase in the wages of a few highly skilled positions. Though these workers individually made more money, their employers secured a precipitous decrease in average wages. Previously, a gang composed entirely of general-purpose butchers might all be paid 35 cents an hour. In the new regime, a few highly specialised butchers would receive 50 cents or more an hour, but the majority of other workers would be paid much less than 35 cents. Highly paid workers were given the only jobs in which costly mistakes could be made – damage to hides or expensive cuts of meat – protecting against mistakes or sabotage from the irregularly employed workers. The packers also believed (sometimes erroneously) that the highly paid workers – popularly known as the “butcher aristocracy” – would be more loyal to management and less willing to cooperate with unionisation attempts.

The overall trend was an incredible intensification of output. Splitters, one of the most skilled positions, provide a good example. The economist John Commons wrote that in 1884, “five splitters in a certain gang would get out 800 cattle in 10 hours, or 16 per hour for each man, the wages being 45 cents. In 1894 the speed had been increased so that four splitters got out 1,200 in 10 hours, or 30 per hour for each man – an increase of nearly 100% in 10 years.” Even as the pace increased, the process of de-skilling ensured that wages were constantly moving downward, forcing employees to work harder for less money.

The fact that meatpacking’s profitability depended on a brutal labour regime meant conflicts between labour and management were ongoing, and at times violent. For workers, strikes during the 1880s and 90s were largely unsuccessful. This was the result of state support for management, a willing pool of replacement workers and extreme hostility to any attempts to organise. At the first sign of unrest, Chicago packers would recruit replacement workers from across the US and threaten to permanently fire and blacklist anyone associated with labour organisers. But state support mattered most of all; during an 1886 fight, for instance, authorities “garrisoned over 1,000 men … to preserve order and protect property”. Even when these troops did not clash with strikers, it had a chilling effect on attempts to organise. Ultimately, packinghouse workers could not organise effectively until the very end of the 19th century.

The genius of the disassembly line was not merely in creating productivity gains through the division of labour; it was also that it simplified labour enough that the Big Four could benefit from a growing surplus of workers and a business-friendly legal regime. If the meatpackers needed purely skilled labour, they could not exploit desperate throngs outside their gates. If a new worker could be trained in hours and government was willing to break strikes and limit injury liability, workers became disposable. This enabled the dangerous – and profitable – increases in production speed that maimed Vincentz Rutkowski.

Centralisation of cattle slaughter in Chicago promised high profits. Chicago’s stockyards had started as a clearinghouse for cattle – a point from which animals were shipped live to cities around the country. But when an animal is shipped live, almost 40% of the travelling weight is blood, bones, hide and other inedible parts. The small slaughterhouses and butchers that bought live animals in New York or Boston could sell some of these by-products to tanners or fertiliser manufacturers, but their ability to do so was limited. If the animals could be slaughtered in Chicago, the large packinghouses could realise massive economies of scale on the by-products. In fact, these firms could undersell local slaughterhouses on the actual meat and make their profits on the by-products.

This model only became possible with refinements in refrigerated shipping technology, starting in the 1870s. Yet simply because technology created a possibility did not make its adoption inevitable. Refrigeration sparked a nearly decade-long conflict between the meatpackers and the railroads. American railroads had invested heavily in railcars and other equipment for shipping live cattle, and fought dressed-beef shipment tonne by tonne, charging different prices for moving a given weight of dressed beef from a similar weight of live cattle. They justified this difference by claiming their goal was to provide the same final cost for beef to consumers – what the railroads called a “principle of neutrality”.

Since beef from animals slaughtered locally was more expensive than Chicago dressed beef, the railroads would charge the Chicago packers more to even things out. This would protect railroad investments by eliminating the packers’ edge, and it could all be justified as “neutral”. Though this succeeded for a time, the packers would defeat this strategy by taking a circuitous route along Canada’s Grand Trunk Railway, a line that was happy to accept dressed-beef business it had no chance of securing otherwise.

Eventually, American railroads abandoned their differential pricing as they saw the collapse of live cattle shipping and became greedy for a piece of the burgeoning dressed-beef trade. But even this was not enough to secure the dominance of the Chicago houses. They also had to contend with local butchers.

In 1889 Henry Barber entered Ramsey County, Minnesota, with 100lb of contraband: fresh beef from an animal slaughtered in Chicago. Barber was no fly-by-night butcher, and was well aware of an 1889 law requiring all meat sold in Minnesota to be inspected locally prior to slaughter. Shortly after arriving, he was arrested, convicted and sentenced to 30 days in jail. But with the support of his employer, Armour & Co, Barber aggressively challenged the local inspection measure.

‘Cows carry flesh, but they carry personality too’: the hard lessons of farming

Today, most local butchers have gone bankrupt and marginal ranchers have had little choice but to accept their marginality. In the US, an increasingly punitive immigration regime makes slaughterhouse work ever more precarious, and “ag-gag” laws that define animal-rights activism as terrorism keep slaughterhouses out of the public eye. The result is that our means of producing our food can seem inevitable, whatever creeping sense of unease consumers might feel. But the history of the beef industry reminds us that this method of producing food is a question of politics and political economy, rather than technology and demographics. Alternate possibilities remain hazy, but if we understand this story as one of political economy, we might be able to fulfil Armour & Company’s old credo – “We feed the world”– using a more equitable system.

The meatpacking mogul Jonathan Ogden Armour could not abide socialist agitators. It was 1906, and Upton Sinclair had just published The Jungle, an explosive novel revealing the grim underside of the American meatpacking industry. Sinclair’s book told the tale of an immigrant family’s toil in Chicago’s slaughterhouses, tracing the family’s physical, financial and emotional collapse. The Jungle was not Armour’s only concern. The year before, the journalist Charles Edward Russell’s book The Greatest Trust in the World had detailed the greed and exploitation of a packing industry that came to the American dining table “three times a day … and extorts its tribute”.

In response to these attacks, Armour, head of the enormous Chicago-based meatpacking firm Armour & Co, took to the Saturday Evening Post to defend himself and his industry. Where critics saw filth, corruption and exploitation, Armour saw cleanliness, fairness and efficiency. If it were not for “the professional agitators of the country”, he claimed, the nation would be free to enjoy an abundance of delicious and affordable meat.

Armour and his critics could agree on this much: they lived in a world unimaginable 50 years before. In 1860, most cattle lived, died and were consumed within a few hundred miles’ radius. By 1906, an animal could be born in Texas, slaughtered in Chicago and eaten in New York. Americans rich and poor could expect to eat beef for dinner. The key aspects of modern beef production – highly centralised, meatpacker-dominated and low-cost – were all pioneered during that period.

For Armour, cheap beef and a thriving centralised meatpacking industry were the consequence of emerging technologies such as the railroad and refrigeration coupled with the business acumen of a set of honest and hard-working men like his father, Philip Danforth Armour. According to critics, however, a capitalist cabal was exploiting technological change and government corruption to bankrupt traditional butchers, sell diseased meat and impoverish the worker.

Ultimately, both views were correct. The national market for fresh beef was the culmination of a technological revolution, but it was also the result of collusion and predatory pricing. The industrial slaughterhouse was a triumph of human ingenuity as well as a site of brutal labour exploitation. Industrial beef production, with all its troubling costs and undeniable benefits, reflected seemingly contradictory realities.

Beef production would also help drive far-reaching changes in US agriculture. Fresh-fruit distribution began with the rise of the meatpackers’ refrigerator cars, which they rented to fruit and vegetable growers. Production of wheat, perhaps the US’s greatest food crop, bore the meatpackers’ mark. In order to manage animal feed costs, Armour & Co and Swift & Co invested heavily in wheat futures and controlled some of the country’s largest grain elevators. In the early 20th century, an Armour & Co promotional map announced that “the greatness of the United States is founded on agriculture”, and depicted the agricultural products of each US state, many of which moved through Armour facilities.

Beef was a paradigmatic industry for the rise of modern industrial agriculture, or agribusiness. As much as a story of science or technology, modern agriculture is a compromise between the unpredictability of nature and the rationality of capital. This was a lurching, violent process that sawmeatpackers displace the risks of blizzards, drought, disease and overproduction on to cattle ranchers. Today’s agricultural system works similarly. In poultry, processors like Perdue and Tyson use an elaborate system of contracts and required equipment and feed purchases to maximise their own profits while displacing risk on to contract farmers. This is true with crop production as well. As with 19th-century meatpacking, relatively small actors conduct the actual growing and production, while companies like Monsanto and Cargill control agricultural inputs and market access.

The transformations that remade beef production between the end of the American civil war in 1865 and the passage of the Federal Meat Inspection Act in 1906 stretched from the Great Plains to the kitchen table. Before the civil war, cattle raising was largely regional, and in most cases, the people who managed cattle out west were the same people who owned them. Then, in the 1870s and 80s, improved transport, bloody victories over the Plains Indians, and the American west’s integration into global capital markets sparked a ranching boom. Meanwhile, Chicago meatpackers pioneered centralised food processing. Using an innovative system of refrigerator cars and distribution centres, they began to distribute fresh beef nationwide. Millions of cattle were soon passing through Chicago’s slaughterhouses each year. By 1890, the Big Four meatpacking companies – Armour & Co, Swift & Co, Morris & Co and the GH Hammond Co – directly or indirectly controlled the majority of the nation’s beef and pork.

But in the 1880s, the big Chicago meatpackers faced determined opposition at every stage from slaughter to sale. Meatpackers fought with workers as they imposed a brutally exploitative labour regime. Meanwhile, attempts to transport freshly butchered beef faced opposition from railroads who found higher profits transporting live cattle east out of Chicago and to local slaughterhouses in eastern cities. Once pre-slaughtered and partially processed beef – known as “dressed beef” – reached the nation’s many cities and towns, the packers fought to displace traditional butchers and woo consumers sceptical of eating meat from an animal slaughtered a continent away.

The consequences of each of these struggles persist today. A small number of firms still control most of the country’s – and by now the world’s – beef. They draw from many comparatively small ranchers and cattle feeders, and depend on a low-paid, mostly invisible workforce. The fact that this set of relationships remains so stable, despite the public’s abstract sense that something is not quite right, is not the inevitable consequence of technological change but the direct result of the political struggles of the late 19th century.

In the slaughterhouse, someone was always willing to take your place. This could not have been far from the mind of 14-year-old Vincentz Rutkowski as he stooped, knife in hand, in a Swift & Co facility in summer 1892. For up to 10 hours each day, Vincentz trimmed tallow from cattle paunches. The job required strong workers who were low to the ground, making it ideal for boys like Rutkowski, who had the beginnings of the strength but not the size of grown men. For the first two weeks of his employment, Rutkowski shared his job with two other boys. As they became more skilled, one of the boys was fired. Another few weeks later, the other was also removed, and Rutkowski was expected to do the work of three people.

The morning that final co-worker left, on 30 June, Rutkowski fell behind the disassembly line’s frenetic pace. After just three hours of working alone, the boy failed to dodge a carcass swinging toward him. It struck his knife hand, driving the tool into his left arm near the elbow. The knife cut muscle and tendon, leaving Rutkowski with lifelong injuries.

The labour regime that led to Rutkowski’s injury was integral to large-scale meatpacking. A packinghouse was a masterpiece of technological and organisational achievement, but that was not enough to slaughter millions of cattle annually. Packing plants needed cheap, reliable and desperate labour. They found it via the combination of mass immigration and a legal regime that empowered management, checked the nascent power of unions and provided limited liability for worker injury. The Big Four’s output depended on worker quantity over worker quality.

Meatpacking lines, pioneered in the 1860s in Cincinnati’s pork packinghouses, were the first modern production lines. The innovation was that they kept products moving continuously, eliminating downtime and requiring workers to synchronise their movements to keep pace. This idea was enormously influential. In his memoirs, Henry Ford explained that his idea for continuous motion assembly “came in a general way from the overhead trolley that the Chicago packers use in dressing beef”.

A Swift and Company meatpacking house in Chicago, circa 1906. Photograph: Granger Historical Picture Archive/Alamy

Packing plants relied on a brilliant intensification of the division of labour. This division increased productivity because it simplified slaughter tasks. Workers could then be trained quickly, and because the tasks were also synchronised, everyone had to match the pace of the fastest worker.

When cattle first entered one of these slaughterhouses, they encountered an armed man walking toward them on an overhead plank. Whether by a hammer swing to the skull or a spear thrust to the animal’s spinal column, the (usually achieved) goal was to kill with a single blow. Assistants chained the animal’s legs and dragged the carcass from the room. The carcass was hoisted into the air and brought from station to station along an overhead rail.

Next, a worker cut the animal’s throat and drained and collected its blood while another group began skinning the carcass. Even this relatively simple process was subdivided throughout the period. Initially the work of a pair, nine different workers handled skinning by 1904. Once the carcass was stripped, gutted and drained of blood, it went into another room, where highly trained butchers cut the carcass into quarters. These quarters were stored in giant refrigerated rooms to await distribution.

But profitability was not just about what happened inside slaughterhouses. It also depended on what was outside: throngs of men and women hoping to find a day’s or a week’s employment. An abundant labour supply meant the packers could easily replace anyone who balked at paltry salaries or, worse yet, tried to unionise. Similarly, productivity increases heightened the risk of worker injury, and therefore were only effective if people could be easily replaced. Fortunately for the packers, late 19th-century Chicago was full of people desperate for work.

Seasonal fluctuations and the vagaries of the nation’s cattle markets further conspired to marginalise slaughterhouse labour. Though refrigeration helped the meatpackers “defeat the seasons” and secure year-round shipping, packing remained seasonal. Packers had to reckon with cattle’s reproductive cycles, and distribution in hot weather was more expensive. The number of animals processed varied day to day and month to month. For packinghouse workers, the effect was a world in which an individual day’s labour might pay relatively well but busy days were punctuated with long stretches of little or no work. The least skilled workers might only find a few weeks or months of employment at a time.

The work was so competitive and the workers so desperate that, even when they had jobs, they often had to wait, without pay, if there were no animals to slaughter. Workers would be fired if they did not show up at a specified time before 9am, but then might wait, unpaid, until 10am or 11am for a shipment. If the delivery was very late, work might continue until late into the night.

Though the division of labour and throngs of unemployed people were crucial to operating the Big Four’s disassembly lines, these factors were not sufficient to maintain a relentless production pace. This required intervention directly on the line. Fortunately for the packers, they could exploit a core aspect of continuous-motion processing: if one person went faster, everyone had to go faster. The meatpackers used pace-setters to force other workers to increase their speed. The packers would pay this select group – roughly one in 10 workers – higher wages and offer secure positions that they only kept if they maintained a rapid pace, forcing the rest of the line to keep up. These pace-setters were resented by their co-workers, and were a vital management tool.

Close supervision of foremen was equally important. Management kept statistics on production-line output, and overseers who slipped in production could lose their jobs. This encouraged foremen to use tactics that management did not want to explicitly support. According to one retired foreman, he was “always trying to cut down wages in every possible way … some of [the foremen] got a commission on all expenses they could save below a certain point”. Though union officials vilified foremen, their jobs were only marginally less tenuous than those of their underlings.

Union Stock Yard in Chicago in 1909. Photograph: Science History Images/Alamy

The effectiveness of de-skilling on the disassembly line rested on an increase in the wages of a few highly skilled positions. Though these workers individually made more money, their employers secured a precipitous decrease in average wages. Previously, a gang composed entirely of general-purpose butchers might all be paid 35 cents an hour. In the new regime, a few highly specialised butchers would receive 50 cents or more an hour, but the majority of other workers would be paid much less than 35 cents. Highly paid workers were given the only jobs in which costly mistakes could be made – damage to hides or expensive cuts of meat – protecting against mistakes or sabotage from the irregularly employed workers. The packers also believed (sometimes erroneously) that the highly paid workers – popularly known as the “butcher aristocracy” – would be more loyal to management and less willing to cooperate with unionisation attempts.

The overall trend was an incredible intensification of output. Splitters, one of the most skilled positions, provide a good example. The economist John Commons wrote that in 1884, “five splitters in a certain gang would get out 800 cattle in 10 hours, or 16 per hour for each man, the wages being 45 cents. In 1894 the speed had been increased so that four splitters got out 1,200 in 10 hours, or 30 per hour for each man – an increase of nearly 100% in 10 years.” Even as the pace increased, the process of de-skilling ensured that wages were constantly moving downward, forcing employees to work harder for less money.

The fact that meatpacking’s profitability depended on a brutal labour regime meant conflicts between labour and management were ongoing, and at times violent. For workers, strikes during the 1880s and 90s were largely unsuccessful. This was the result of state support for management, a willing pool of replacement workers and extreme hostility to any attempts to organise. At the first sign of unrest, Chicago packers would recruit replacement workers from across the US and threaten to permanently fire and blacklist anyone associated with labour organisers. But state support mattered most of all; during an 1886 fight, for instance, authorities “garrisoned over 1,000 men … to preserve order and protect property”. Even when these troops did not clash with strikers, it had a chilling effect on attempts to organise. Ultimately, packinghouse workers could not organise effectively until the very end of the 19th century.

The genius of the disassembly line was not merely in creating productivity gains through the division of labour; it was also that it simplified labour enough that the Big Four could benefit from a growing surplus of workers and a business-friendly legal regime. If the meatpackers needed purely skilled labour, they could not exploit desperate throngs outside their gates. If a new worker could be trained in hours and government was willing to break strikes and limit injury liability, workers became disposable. This enabled the dangerous – and profitable – increases in production speed that maimed Vincentz Rutkowski.

Centralisation of cattle slaughter in Chicago promised high profits. Chicago’s stockyards had started as a clearinghouse for cattle – a point from which animals were shipped live to cities around the country. But when an animal is shipped live, almost 40% of the travelling weight is blood, bones, hide and other inedible parts. The small slaughterhouses and butchers that bought live animals in New York or Boston could sell some of these by-products to tanners or fertiliser manufacturers, but their ability to do so was limited. If the animals could be slaughtered in Chicago, the large packinghouses could realise massive economies of scale on the by-products. In fact, these firms could undersell local slaughterhouses on the actual meat and make their profits on the by-products.

This model only became possible with refinements in refrigerated shipping technology, starting in the 1870s. Yet simply because technology created a possibility did not make its adoption inevitable. Refrigeration sparked a nearly decade-long conflict between the meatpackers and the railroads. American railroads had invested heavily in railcars and other equipment for shipping live cattle, and fought dressed-beef shipment tonne by tonne, charging different prices for moving a given weight of dressed beef from a similar weight of live cattle. They justified this difference by claiming their goal was to provide the same final cost for beef to consumers – what the railroads called a “principle of neutrality”.

Since beef from animals slaughtered locally was more expensive than Chicago dressed beef, the railroads would charge the Chicago packers more to even things out. This would protect railroad investments by eliminating the packers’ edge, and it could all be justified as “neutral”. Though this succeeded for a time, the packers would defeat this strategy by taking a circuitous route along Canada’s Grand Trunk Railway, a line that was happy to accept dressed-beef business it had no chance of securing otherwise.

Eventually, American railroads abandoned their differential pricing as they saw the collapse of live cattle shipping and became greedy for a piece of the burgeoning dressed-beef trade. But even this was not enough to secure the dominance of the Chicago houses. They also had to contend with local butchers.

In 1889 Henry Barber entered Ramsey County, Minnesota, with 100lb of contraband: fresh beef from an animal slaughtered in Chicago. Barber was no fly-by-night butcher, and was well aware of an 1889 law requiring all meat sold in Minnesota to be inspected locally prior to slaughter. Shortly after arriving, he was arrested, convicted and sentenced to 30 days in jail. But with the support of his employer, Armour & Co, Barber aggressively challenged the local inspection measure.

A cattle stockyard in Texas in the 1960s. Photograph: ClassicStock/Alamy

Barber’s arrest was part of a plan to provoke a fight over the Minnesota law, which Armour & Co had lobbied against since it was first drawn up. In federal court, Barber’s lawyers alleged that the statute under which he was convicted violated federal authority over interstate commerce, as well as the US constitution’s privileges and immunities clause. The case would eventually reach the supreme court.

At trial, the state argued that without local, on-the-hoof inspection it was impossible to know if meat had come from a diseased animal. Local inspection was therefore a reasonable part of the state’s police power. Of course, if this argument was upheld, the Chicago houses would no longer be able to ship their goods to any unfriendly state. In response, Barber’s counsel argued that the Minnesota law was a protectionist measure that discriminated against out-of-state butchers. There was no reason meat could not be adequately inspected in Chicago before being sold elsewhere. In Minnesota v Barber (1890), the supreme court ruled the statute unconstitutional and ordered Barber’s release. Armour & Co would go on to dominate the local market.

The Barber ruling was a pivotal moment in a longer fight on the part of the Big Four to secure national distribution. The Minnesota law, and others like it across the country, were fronts in a war waged by local butchers to protect their trade against the encroachment of the “dressed-beef men”. The rise of the Chicago meatpackers was not a gradual process of newer practices displacing old, but a wrenching process of big packers strong-arming and bankrupting smaller competitors. The Barber decision made these fights possible, but it did not make victory inevitable. It was on the back of hundreds of small victories – in rural and urban communities across the US – that the packers built their enormous profits.

Armour and the other big packers did not want to deal directly with customers. That required knowledge of local markets and represented a considerable amount of risk. Instead, they hoped to replace wholesalers, who slaughtered cattle for sale to retail butchers. The Chicago houses wanted local butchers to focus exclusively on selling meat; the packers would handle the rest.

When the packers first entered an area, they wooed a respected butcher. If the butcher would agree to buy from the Chicago houses, he could secure extremely generous rates. But if the local butcher refused these advances, the packers declared war. For example, when the Chicago houses entered Pittsburgh, they approached the veteran butcher William Peters. When he refused to work with Armour & Co, Peters later explained, the Chicago firm’s agent told him: “Mr Peters, if you butchers don’t take hold of it [dressed beef], we are going to open shops throughout the city.” Still, Peters resisted and Armour went on to open its own shops, underselling Pittsburgh’s butchers. Peters told investigators that he and his colleagues “are working for glory now. We do not work for any profit … we have been working for glory for the past three or four years, ever since those fellows came into our town”. Meanwhile, Armour’s share of the Pittsburgh market continued to grow.

Facing these kinds of tactics in cities around the country, local butchers formed protective associations to fight the Chicago houses. Though many associations were local, the Butchers’ National Protective Association of the United States of America aspired to “unite in one brotherhood all butchers and persons engaged in dealing in butchers’ stock”. Organised in 1887, the association pledged to “protect their common interests and those of the general public” through a focus on sanitary conditions. Health concerns were an issue on which traditional butchers could oppose the Chicago houses while appealing to consumers’ collective good. They argued that the Big Four “disregard the public good and endanger the health of the people by selling, for human food, diseased, tainted and other unwholesome meat”. The association further promised to oppose price manipulation of a “staple and indispensable article of human food”.

These associations pushed what amounted to a protectionist agenda using food contamination as a justification. On the state and local level, associations demanded local inspection before slaughter, as was the case with the Minnesota law that Henry Barber challenged. Decentralising slaughter would make wholesale butchering again dependent on local knowledge that the packers could not acquire from Chicago.

But again the packers successfully challenged these measures in the courts. Though the specifics varied by case, judges generally affirmed the argument that local, on-the-hoof inspection violated the constitution’s interstate commerce clause, and often accepted that inspection did not need to be local to ensure safe food. Animals could be inspected in Chicago before slaughter and then the meat itself could be inspected locally. This approach would address public fears about sanitary meat, but without a corresponding benefit to local butchers. Lacking legal recourse and finding little support from consumers excited about low-cost beef, local wholesalers lost more and more ground to the Chicago houses until they disappeared almost entirely.

Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle would become the most famous protest novel of the 20th century. By revealing brutal labour exploitation and stomach-turning slaughterhouse filth, the novel helped spur the passage of the Federal Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906. But The Jungle’s heart-wrenching critique of industrial capitalism was lost on readers more worried about the rat faeces that, according to Sinclair, contaminated their sausage. Sinclair later observed: “I aimed at the public’s heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach.” He hoped for socialist revolution, but had to settle for accurate food labelling.

The industry’s defence against striking workers, angry butchers and bankrupt ranchers – namely, that the new system of industrial production served a higher good – resonated with the public. Abstractly, Americans were worried about the plight of slaughterhouse workers, but they were also wary of those same workers marching in the streets. Similarly, they cared about the struggles of ranchers and local butchers, but also had to worry about their wallets. If packers could provide low prices and reassure the public that their meat was safe, consumers would be happy.

The Big Four meatpacking firms came to control the majority of the US’s beef within a fairly brief period –about 15 years – as a set of relationships that once appeared unnatural began to appear inevitable. Intense de-skilling in slaughterhouse labour only became accepted once organised labour was thwarted, leaving packinghouse labour largely invisible to this day. The slaughter of meat in one place for consumption and sale elsewhere only ceased to appear “artificial and abnormal” once butchers’ protective associations disbanded, and once lawmakers and the public accepted that this centralised industrial system was necessary to provide cheap beef to the people.

These developments are taken for granted now, but they were the product of struggles that could have resulted in radically different standards of production. The beef industry that was established in this period would shape food production throughout the 20th century. There were more major shifts – ranging from trucking-driven decentralisation to the rise of fast food – but the broad strokes would remain the same. Much of the environmental and economic risk of food production would be displaced on to struggling ranchers and farmers, while processors and packers would make money in good times and bad. Benefit to an abstract consumer good would continue to justify the industry’s high environmental and social costs.

Barber’s arrest was part of a plan to provoke a fight over the Minnesota law, which Armour & Co had lobbied against since it was first drawn up. In federal court, Barber’s lawyers alleged that the statute under which he was convicted violated federal authority over interstate commerce, as well as the US constitution’s privileges and immunities clause. The case would eventually reach the supreme court.

At trial, the state argued that without local, on-the-hoof inspection it was impossible to know if meat had come from a diseased animal. Local inspection was therefore a reasonable part of the state’s police power. Of course, if this argument was upheld, the Chicago houses would no longer be able to ship their goods to any unfriendly state. In response, Barber’s counsel argued that the Minnesota law was a protectionist measure that discriminated against out-of-state butchers. There was no reason meat could not be adequately inspected in Chicago before being sold elsewhere. In Minnesota v Barber (1890), the supreme court ruled the statute unconstitutional and ordered Barber’s release. Armour & Co would go on to dominate the local market.

The Barber ruling was a pivotal moment in a longer fight on the part of the Big Four to secure national distribution. The Minnesota law, and others like it across the country, were fronts in a war waged by local butchers to protect their trade against the encroachment of the “dressed-beef men”. The rise of the Chicago meatpackers was not a gradual process of newer practices displacing old, but a wrenching process of big packers strong-arming and bankrupting smaller competitors. The Barber decision made these fights possible, but it did not make victory inevitable. It was on the back of hundreds of small victories – in rural and urban communities across the US – that the packers built their enormous profits.

Armour and the other big packers did not want to deal directly with customers. That required knowledge of local markets and represented a considerable amount of risk. Instead, they hoped to replace wholesalers, who slaughtered cattle for sale to retail butchers. The Chicago houses wanted local butchers to focus exclusively on selling meat; the packers would handle the rest.

When the packers first entered an area, they wooed a respected butcher. If the butcher would agree to buy from the Chicago houses, he could secure extremely generous rates. But if the local butcher refused these advances, the packers declared war. For example, when the Chicago houses entered Pittsburgh, they approached the veteran butcher William Peters. When he refused to work with Armour & Co, Peters later explained, the Chicago firm’s agent told him: “Mr Peters, if you butchers don’t take hold of it [dressed beef], we are going to open shops throughout the city.” Still, Peters resisted and Armour went on to open its own shops, underselling Pittsburgh’s butchers. Peters told investigators that he and his colleagues “are working for glory now. We do not work for any profit … we have been working for glory for the past three or four years, ever since those fellows came into our town”. Meanwhile, Armour’s share of the Pittsburgh market continued to grow.

Facing these kinds of tactics in cities around the country, local butchers formed protective associations to fight the Chicago houses. Though many associations were local, the Butchers’ National Protective Association of the United States of America aspired to “unite in one brotherhood all butchers and persons engaged in dealing in butchers’ stock”. Organised in 1887, the association pledged to “protect their common interests and those of the general public” through a focus on sanitary conditions. Health concerns were an issue on which traditional butchers could oppose the Chicago houses while appealing to consumers’ collective good. They argued that the Big Four “disregard the public good and endanger the health of the people by selling, for human food, diseased, tainted and other unwholesome meat”. The association further promised to oppose price manipulation of a “staple and indispensable article of human food”.

These associations pushed what amounted to a protectionist agenda using food contamination as a justification. On the state and local level, associations demanded local inspection before slaughter, as was the case with the Minnesota law that Henry Barber challenged. Decentralising slaughter would make wholesale butchering again dependent on local knowledge that the packers could not acquire from Chicago.

But again the packers successfully challenged these measures in the courts. Though the specifics varied by case, judges generally affirmed the argument that local, on-the-hoof inspection violated the constitution’s interstate commerce clause, and often accepted that inspection did not need to be local to ensure safe food. Animals could be inspected in Chicago before slaughter and then the meat itself could be inspected locally. This approach would address public fears about sanitary meat, but without a corresponding benefit to local butchers. Lacking legal recourse and finding little support from consumers excited about low-cost beef, local wholesalers lost more and more ground to the Chicago houses until they disappeared almost entirely.

Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle would become the most famous protest novel of the 20th century. By revealing brutal labour exploitation and stomach-turning slaughterhouse filth, the novel helped spur the passage of the Federal Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906. But The Jungle’s heart-wrenching critique of industrial capitalism was lost on readers more worried about the rat faeces that, according to Sinclair, contaminated their sausage. Sinclair later observed: “I aimed at the public’s heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach.” He hoped for socialist revolution, but had to settle for accurate food labelling.

The industry’s defence against striking workers, angry butchers and bankrupt ranchers – namely, that the new system of industrial production served a higher good – resonated with the public. Abstractly, Americans were worried about the plight of slaughterhouse workers, but they were also wary of those same workers marching in the streets. Similarly, they cared about the struggles of ranchers and local butchers, but also had to worry about their wallets. If packers could provide low prices and reassure the public that their meat was safe, consumers would be happy.

The Big Four meatpacking firms came to control the majority of the US’s beef within a fairly brief period –about 15 years – as a set of relationships that once appeared unnatural began to appear inevitable. Intense de-skilling in slaughterhouse labour only became accepted once organised labour was thwarted, leaving packinghouse labour largely invisible to this day. The slaughter of meat in one place for consumption and sale elsewhere only ceased to appear “artificial and abnormal” once butchers’ protective associations disbanded, and once lawmakers and the public accepted that this centralised industrial system was necessary to provide cheap beef to the people.