'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Apple. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Apple. Show all posts

Saturday, 4 November 2023

Monday, 9 December 2019

Sunday, 6 January 2019

Apple and China’s problems show that today’s titans may not rule the world tomorrow

Even superpowers and trillion-dollar tech giants are at risk in a fast-changing society writes Will Hutton in The Guardian

An Apple Store in Beijing, where the company’s sales figures have slumped. Photograph: Wu Hong/EPA

Our mental geography is bounded by what has gone before. What has happened in the recently remembered past is most likely to continue. Inflection points, when trends decisively change, are more infrequent than the many instances when things go on as they have done.

Two of today’s trends seem unstoppable. China’s astounding growth will continue, so the story runs, underwriting its arrival as the second economic superpower. To get a share in that China action, underpinning the entire growth of Asia, is one of the prime economic arguments for Brexit. Abandon sclerotic Europe, embrace the prosperity of Asia – even if it is a world of semi-democracy at best, authoritarian government at worst. It can be guaranteed to grow.

Second, the west coast big tech companies, from Facebook to Apple, are the new wonders of the universe. They are the bewilderingly successful face of the informational, data-driven economy whose value continues to soar. Apple, then Amazon, became the first trillion-dollar corporations last year, both exemplars of how first movers in innovation with their transformative technologies have become 21st-century titans, driving stock market growth and changing society alike.

However, last week, both trends were decisively challenged in what looks like a world-changing inflection moment, one where consensus assumptions start to unravel. Apple announced that for the first time in 17 years it would not meet its forecasts for revenue growth – and by a big margin. Its CEO, Tim Cook, explained to investors and staff that apart from the problems facing all makers of mobile phones – it is becoming a mature market – there was unexpected sales weakness in China. This was not just down to intense competition, but because China’s consumers were spending much less. Apple’s share price plunged – cumulatively, its value has fallen by a stunning $400bn in a couple of months.

China’s total debt, even on distrusted official figures, is approaching three times its GDP

But surely China, landing its robotic satellite on the far side of the moon, is suffering no more than a typical cyclical setback, intensified by Donald Trump’s trade war? Perhaps, but look more closely and it is ever clearer that long-standing problems are starting to envelop this continental economy.

It was only eight years ago that China registered 12% growth as the government turbo-boosted its economy with a massive stimulus in the wake of the financial crisis, growth that staved off a world slump. But since then its official growth rate has been consistently sliding, now halved at 6%, and China’s consumers have started to notice what last year’s 25% fall in China’s stock market is also signalling. Alongside Apple’s statement, last week’s surveys showing China’s famed manufacturing sector is set to decline in 2019 and further weakness in retail sales were more evidence that all is not well. China’s consumers are reading the runes.

Part of the issue for both Apple and China is the law of large numbers. Three-fifths of Apple’s sales are iPhones and there just aren’t enough global consumers with pockets deep enough to keep up the growth momentum. China’s issues are even more profound. There comes a limit, even in a state-controlled economy, to manipulating growth through debt and exports when the numbers reach astronomic levels. China’s total debt, even on distrusted official figures, is approaching three times its GDP, a flashpoint ratio for every economy when bank balance sheets, and their borrowers, just become too overstretched.

This was the trigger for Japan’s economic depression 30 years ago. Moreover, if China’s exports carried on growing as fast as they had, they would crowd out every other export from every country in the world by the mid-2020s. This was never likely, economically or politically. If Trump had not launched his trade offensive, another US leader would have done so. Apple and China, bluntly, are in a fix.

The Chinese Communist party is in a gathering crisis of legitimacy. If the growth rate sinks below 6% (unofficial figures now place growth at under 2% in 2018), its job-generating capacity starts to falter and questions will be asked about the competence of the party. Past leaders have responded to crises by intensifying the pace of transition towards a capitalist economy and boosting infrastructure spending as a quick fix.

These are not options for Xi Jinping. So high has infrastructure spending been for so long that the financial returns to justify further debt are nonexistent. Nor can he free the economy further without endangering the party’s control. His options are a combination of hoping hi-tech, driven by extravagant R&D spending, will offer a stronger economy (along with more repression as a safety fallback and finding enemies around which the country can unite).

The speech last week warning China might go to war to end Taiwan’s independence was the most bellicose of any Chinese leader since Mao. Be in no doubt – if economic difficulties worsen, Xi may be compelled to rally his restive population around a limited conflict just to stay in power.

In a mirror image, Apple is spending as aggressively on R&D as China, hoping that will solve its problems too. Apple is indubitably innovative and the scale of its research should throw up new products; it is already developing a great service business. For China, the message is even starker. A one-party state can’t risk any bumps – and there are more than bumps ahead. Nothing, not even the wondrous success of the iPhone, lasts for ever. And that is especially true for a dysfunctional Chinese economy, and the party that runs it.

Our mental geography is bounded by what has gone before. What has happened in the recently remembered past is most likely to continue. Inflection points, when trends decisively change, are more infrequent than the many instances when things go on as they have done.

Two of today’s trends seem unstoppable. China’s astounding growth will continue, so the story runs, underwriting its arrival as the second economic superpower. To get a share in that China action, underpinning the entire growth of Asia, is one of the prime economic arguments for Brexit. Abandon sclerotic Europe, embrace the prosperity of Asia – even if it is a world of semi-democracy at best, authoritarian government at worst. It can be guaranteed to grow.

Second, the west coast big tech companies, from Facebook to Apple, are the new wonders of the universe. They are the bewilderingly successful face of the informational, data-driven economy whose value continues to soar. Apple, then Amazon, became the first trillion-dollar corporations last year, both exemplars of how first movers in innovation with their transformative technologies have become 21st-century titans, driving stock market growth and changing society alike.

However, last week, both trends were decisively challenged in what looks like a world-changing inflection moment, one where consensus assumptions start to unravel. Apple announced that for the first time in 17 years it would not meet its forecasts for revenue growth – and by a big margin. Its CEO, Tim Cook, explained to investors and staff that apart from the problems facing all makers of mobile phones – it is becoming a mature market – there was unexpected sales weakness in China. This was not just down to intense competition, but because China’s consumers were spending much less. Apple’s share price plunged – cumulatively, its value has fallen by a stunning $400bn in a couple of months.

China’s total debt, even on distrusted official figures, is approaching three times its GDP

But surely China, landing its robotic satellite on the far side of the moon, is suffering no more than a typical cyclical setback, intensified by Donald Trump’s trade war? Perhaps, but look more closely and it is ever clearer that long-standing problems are starting to envelop this continental economy.

It was only eight years ago that China registered 12% growth as the government turbo-boosted its economy with a massive stimulus in the wake of the financial crisis, growth that staved off a world slump. But since then its official growth rate has been consistently sliding, now halved at 6%, and China’s consumers have started to notice what last year’s 25% fall in China’s stock market is also signalling. Alongside Apple’s statement, last week’s surveys showing China’s famed manufacturing sector is set to decline in 2019 and further weakness in retail sales were more evidence that all is not well. China’s consumers are reading the runes.

Part of the issue for both Apple and China is the law of large numbers. Three-fifths of Apple’s sales are iPhones and there just aren’t enough global consumers with pockets deep enough to keep up the growth momentum. China’s issues are even more profound. There comes a limit, even in a state-controlled economy, to manipulating growth through debt and exports when the numbers reach astronomic levels. China’s total debt, even on distrusted official figures, is approaching three times its GDP, a flashpoint ratio for every economy when bank balance sheets, and their borrowers, just become too overstretched.

This was the trigger for Japan’s economic depression 30 years ago. Moreover, if China’s exports carried on growing as fast as they had, they would crowd out every other export from every country in the world by the mid-2020s. This was never likely, economically or politically. If Trump had not launched his trade offensive, another US leader would have done so. Apple and China, bluntly, are in a fix.

The Chinese Communist party is in a gathering crisis of legitimacy. If the growth rate sinks below 6% (unofficial figures now place growth at under 2% in 2018), its job-generating capacity starts to falter and questions will be asked about the competence of the party. Past leaders have responded to crises by intensifying the pace of transition towards a capitalist economy and boosting infrastructure spending as a quick fix.

These are not options for Xi Jinping. So high has infrastructure spending been for so long that the financial returns to justify further debt are nonexistent. Nor can he free the economy further without endangering the party’s control. His options are a combination of hoping hi-tech, driven by extravagant R&D spending, will offer a stronger economy (along with more repression as a safety fallback and finding enemies around which the country can unite).

The speech last week warning China might go to war to end Taiwan’s independence was the most bellicose of any Chinese leader since Mao. Be in no doubt – if economic difficulties worsen, Xi may be compelled to rally his restive population around a limited conflict just to stay in power.

In a mirror image, Apple is spending as aggressively on R&D as China, hoping that will solve its problems too. Apple is indubitably innovative and the scale of its research should throw up new products; it is already developing a great service business. For China, the message is even starker. A one-party state can’t risk any bumps – and there are more than bumps ahead. Nothing, not even the wondrous success of the iPhone, lasts for ever. And that is especially true for a dysfunctional Chinese economy, and the party that runs it.

Monday, 19 June 2017

Life and death in Apple’s forbidden city - Shame on you Steve Jobs

Brian Merchant in The Guardian

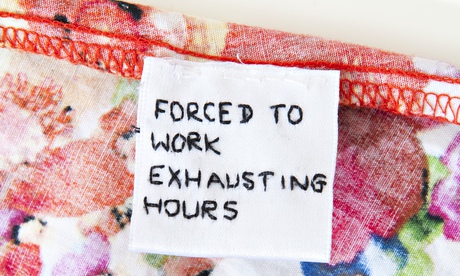

The sprawling factory compound, all grey dormitories and weather-beaten warehouses, blends seamlessly into the outskirts of the Shenzhen megalopolis. Foxconn’s enormous Longhua plant is a major manufacturer of Apple products. It might be the best-known factory in the world; it might also might be among the most secretive and sealed-off. Security guards man each of the entry points. Employees can’t get in without swiping an ID card; drivers entering with delivery trucks are subject to fingerprint scans. A Reuters journalist was once dragged out of a car and beaten for taking photos from outside the factory walls. The warning signs outside – “This factory area is legally established with state approval. Unauthorised trespassing is prohibited. Offenders will be sent to police for prosecution!” – are more aggressive than those outside many Chinese military compounds.

But it turns out that there’s a secret way into the heart of the infamous operation: use the bathroom. I couldn’t believe it. Thanks to a simple twist of fate and some clever perseverance by my fixer, I’d found myself deep inside so-called Foxconn City.

It’s printed on the back of every iPhone: “Designed by Apple in California Assembled in China”. US law dictates that products manufactured in China must be labelled as such and Apple’s inclusion of the phrase renders the statement uniquely illustrative of one of the planet’s starkest economic divides – the cutting edge is conceived and designed in Silicon Valley, but it is assembled by hand in China.

The vast majority of plants that produce the iPhone’s component parts and carry out the device’s final assembly are based here, in the People’s Republic, where low labour costs and a massive, highly skilled workforce have made the nation the ideal place to manufacture iPhones (and just about every other gadget). The country’s vast, unprecedented production capabilities – the US Bureau of Labor Statistics estimated that as of 2009 there were 99 million factory workers in China – have helped the nation become the world’s second largest economy. And since the first iPhone shipped, the company doing the lion’s share of the manufacturing is the Taiwanese Hon Hai Precision Industry Co, Ltd, better known by its trade name, Foxconn.

Foxconn is the single largest employer in mainland China; there are 1.3 million people on its payroll. Worldwide, among corporations, only Walmart and McDonald’s employ more. As many people work for Foxconn as live in Estonia.

An employee directs jobseekers to queue up at the Foxconn recruitment centre in Shenzhen. Photograph: David Johnson/Reuters

Today, the iPhone is made at a number of different factories around China, but for years, as it became the bestselling product in the world, it was largely assembled at Foxconn’s 1.4 square-mile flagship plant, just outside Shenzhen. The sprawling factory was once home to an estimated 450,000 workers. Today, that number is believed to be smaller, but it remains one of the biggest such operations in the world. If you know of Foxconn, there’s a good chance it’s because you’ve heard of the suicides. In 2010, Longhua assembly-line workers began killing themselves. Worker after worker threw themselves off the towering dorm buildings, sometimes in broad daylight, in tragic displays of desperation – and in protest at the work conditions inside. There were 18 reported suicide attempts that year alone and 14 confirmed deaths. Twenty more workers were talked down by Foxconn officials.

The epidemic caused a media sensation – suicides and sweatshop conditions in the House of iPhone. Suicide notes and survivors told of immense stress, long workdays and harsh managers who were prone to humiliate workers for mistakes, of unfair fines and unkept promises of benefits.

The corporate response spurred further unease: Foxconn CEO, Terry Gou, had large nets installed outside many of the buildings to catch falling bodies. The company hired counsellors and workers were made to sign pledges stating they would not attempt to kill themselves.

Steve Jobs, for his part, declared: “We’re all over that” when asked about the spate of deaths and he pointed out that the rate of suicides at Foxconn was within the national average. Critics pounced on the comment as callous, though he wasn’t technically wrong. Foxconn Longhua was so massive that it could be its own nation-state, and the suicide rate was comparable to its host country’s. The difference is that Foxconn City is a nation-state governed entirely by a corporation and one that happened to be producing one of the most profitable products on the planet.

If the boss finds any problems, they don’t scold you then. They scold you later, in front of everyone, at a meeting

A cab driver lets us out in front of the factory; boxy blue letters spell out Foxconn next to the entrance. The security guards eye us, half bored, half suspicious. My fixer, a journalist from Shanghai whom I’ll call Wang Yang, and I decide to walk the premises first and talk to workers, to see if there might be a way to get inside.

The first people we stop turn out to be a pair of former Foxconn workers.

“It’s not a good place for human beings,” says one of the young men, who goes by the name Xu. He’d worked in Longhua for about a year, until a couple of months ago, and he says the conditions inside are as bad as ever. “There is no improvement since the media coverage,” Xu says. The work is very high pressure and he and his colleagues regularly logged 12-hour shifts. Management is both aggressive and duplicitous, publicly scolding workers for being too slow and making them promises they don’t keep, he says. His friend, who worked at the factory for two years and chooses to stay anonymous, says he was promised double pay for overtime hours but got only regular pay. They paint a bleak picture of a high-pressure working environment where exploitation is routine and where depression and suicide have become normalised.

“It wouldn’t be Foxconn without people dying,” Xu says. “Every year people kill themselves. They take it as a normal thing.”

Over several visits to different iPhone assembly factories in Shenzhen and Shanghai, we interviewed dozens of workers like these. Let’s be honest: to get a truly representative sample of life at an iPhone factory would require a massive canvassing effort and the systematic and clandestine interviewing of thousands of employees. So take this for what it is: efforts to talk to often skittish, often wary and often bored workers who were coming out of the factory gates, taking a lunch break or congregating after their shifts.

A Foxconn employee in a dormitory at Longhua. The rooms are currently said to sleep eight. Photograph: Wang Yishu / Imaginechina/Camera Press

The vision of life inside an iPhone factory that emerged was varied. Some found the work tolerable; others were scathing in their criticisms; some had experienced the despair Foxconn was known for; still others had taken a job just to try to find a girlfriend. Most knew of the reports of poor conditions before joining, but they either needed the work or it didn’t bother them. Almost everywhere, people said the workforce was young and turnover was high. “Most employees last only a year,” was a common refrain. Perhaps that’s because the pace of work is widely agreed to be relentless, and the management culture is often described as cruel.

Since the iPhone is such a compact, complex machine, putting one together correctly requires sprawling assembly lines of hundreds of people who build, inspect, test and package each device. One worker said 1,700 iPhones passed through her hands every day; she was in charge of wiping a special polish on the display. That works out at about three screens a minute for 12 hours a day.

More meticulous work, like fastening chip boards and assembling back covers, was slower; these workers have a minute apiece for each iPhone. That’s still 600 to 700 iPhones a day. Failing to meet a quota or making a mistake can draw public condemnation from superiors. Workers are often expected to stay silent and may draw rebukes from their bosses for asking to use the restroom.

Xu and his friend were both walk-on recruits, though not necessarily willing ones. “They call Foxconn a fox trap,” he says. “Because it tricks a lot of people.” He says Foxconn promised them free housing but then forced them to pay exorbitantly high bills for electricity and water. The current dorms sleep eight to a room and he says they used to be 12 to a room. But Foxconn would shirk social insurance and be late or fail to pay bonuses. And many workers sign contracts that subtract a hefty penalty from their pay if they quit before a three-month introductory period.

The body-catching nets are still there. They look a bit like tarps that have blown off the things they’re meant to cover

On top of that, the work is gruelling. “You have to have mental management,” says Xu, otherwise you can get scolded by bosses in front of your peers. Instead of discussing performance privately or face to face on the line, managers would stockpile complaints until later. “When the boss comes down to inspect the work,” Xu’s friend says, “if they find any problems, they won’t scold you then. They will scold you in front of everyone in a meeting later.”

“It’s insulting and humiliating to people all the time,” his friend says. “Punish someone to make an example for everyone else. It’s systematic,” he adds. In certain cases, if a manager decides that a worker has made an especially costly mistake, the worker has to prepare a formal apology. “They must read a promise letter aloud – ‘I won’t make this mistake again’– to everyone.”

This culture of high-stress work, anxiety and humiliation contributes to widespread depression. Xu says there was another suicide a few months ago. He saw it himself. The man was a student who worked on the iPhone assembly line. “Somebody I knew, somebody I saw around the cafeteria,” he says. After being publicly scolded by a manager, he got into a quarrel. Company officials called the police, though the worker hadn’t been violent, just angry.

“He took it very personally,” Xu says, “and he couldn’t get through it.” Three days later, he jumped out of a ninth-storey window.

So why didn’t the incident get any media coverage? I ask. Xu and his friend look at each other and shrug. “Here someone dies, one day later the whole thing doesn’t exist,” his friend says. “You forget about it.”

Employees have lunch in a vast refectory at the Foxconn Longhua plant. Photograph: Wang Yishu/Imaginechina/Camera Press

‘We look at everything at these companies,” Steve Jobs said after news of the suicides broke. “Foxconn is not a sweatshop. It’s a factory – but my gosh, they have restaurants and movie theatres… but it’s a factory. But they’ve had some suicides and attempted suicides – and they have 400,000 people there. The rate is under what the US rate is, but it’s still troubling.” Apple CEO, Tim Cook, visited Longhua in 2011 and reportedly met suicide-prevention experts and top management to discuss the epidemic.

In 2012, 150 workers gathered on a rooftop and threatened to jump. They were promised improvements and talked down by management; they had, essentially, wielded the threat of killing themselves as a bargaining tool. In 2016, a smaller group did it again. Just a month before we spoke, Xu says, seven or eight workers gathered on a rooftop and threatened to jump unless they were paid the wages they were due, which had apparently been withheld. Eventually, Xu says, Foxconn agreed to pay the wages and the workers were talked down.

When I ask Xu about Apple and the iPhone, his response is swift: “We don’t blame Apple. We blame Foxconn.” When I ask the men if they would consider working at Foxconn again if the conditions improved, the response is equally blunt. “You can’t change anything,” Xu says. “It will never change.”

Wang and I set off for the main worker entrance. We wind around the perimeter, which stretches on and on – we have no idea this is barely a fraction of the factory at this point.

After walking along the perimeter for 20 minutes or so, we come to another entrance, another security checkpoint. That’s when it hits me. I have to use the bathroom. Desperately. And that gives me an idea.

There’s a bathroom in there, just a few hundred feet down a stairwell by the security point. I see the universal stick-man signage and I gesture to it. This checkpoint is much smaller, much more informal. There’s only one guard, a young man who looks bored. Wang asks something a little pleadingly in Chinese. The guard slowly shakes his head no, looks at me. The strain on my face is very, very real. She asks again – he falters for a second, then another no.

We’ll be right back, she insists, and now we’re clearly making him uncomfortable. Mostly me. He doesn’t want to deal with this. Come right back, he says. Of course, we don’t.

To my knowledge, no American journalist has been inside a Foxconn plant without permission and a tour guide, without a carefully curated visit to selected parts of the factory to demonstrate how OK things really are.

Maybe the most striking thing, beyond its size – it would take us nearly an hour to briskly walk across Longhua – is how radically different one end is from the other. It’s like a gentrified city in that regard. On the outskirts, let’s call them, there are spilt chemicals, rusting facilities and poorly overseen industrial labour. The closer you get to the city centre – remember, this is a factory – the more the quality of life, or at least the amenities and the infrastructure, improves.

‘Not a good place for human beings’: Foxconn Longhua. Photograph: Brian Merchant

As we get deeper in, surrounded by more and more people, it feels like we’re getting noticed less. The barrage of stares mutates into disinterested glances. My working theory: the plant is so vast, security so tight, that if we are inside just walking around, we must have been allowed to do so. That or nobody really gives a shit. We start trying to make our way to the G2 factory block, where we’ve been told iPhones are made. After leaving “downtown”, we begin seeing towering, monolithic factory blocks – C16, E7 and so on, many surrounded by crowds of workers.

I worry about getting too cavalier and remind myself not to push it; we’ve been inside Foxconn for almost an hour now. The crowds have been thinning out the farther away from the centre we get. Then there it is: G2. It’s identical to the factory blocks that cluster around it, that threaten to fade into the background of the smoggy static sky.

G2 looks deserted, though. A row of impossibly rusted lockers runs outside the building. No one’s around. The door is open, so we go in. To the left, there’s an entry to a massive, darkened space; we’re heading for that when someone calls out. A floor manager has just come down the stairs and he asks us what we’re doing. My translator stammers something about a meeting and the man looks confused; then he shows us the computer monitoring system he uses to oversee production on the floor. There’s no shift right now, he says, but this is how they watch.

No sign of iPhones, though. We keep walking. Outside G3, teetering stacks of black gadgets wrapped in plastic sit in front of what looks like another loading zone. A couple of workers on smartphones drift by us. We get close enough to see the gadgets through the plastic and, nope, not iPhones either. They look like Apple TVs, minus the company logo. There are probably thousands stacked here, awaiting the next step in the assembly line.

If this is indeed where iPhones and Apple TVs are made, it’s a fairly aggressively shitty place to spend long days, unless you have a penchant for damp concrete and rust. The blocks keep coming, so we keep walking. Longhua starts to feel like the dull middle of a dystopian novel, where the dread sustains but the plot doesn’t.

We could keep going, but to our left, we see what look like large housing complexes, probably the dormitories, complete with cagelike fences built out over the roof and the windows, and so we head in that direction. The closer we get to the dorms, the thicker the crowds get and the more lanyards and black glasses and faded jeans and sneakers we see. College-age kids are gathered, smoking cigarettes, crowded around picnic tables, sitting on kerbs.

And, yes, the body-catching nets are still there. Limp and sagging, they give the impression of tarps that have half blown off the things they’re supposed to cover. I think of Xu, who said: “The nets are pointless. If somebody wants to commit suicide, they will do it.”

We are drawing stares again – away from the factories, maybe folks have more time and reason to indulge their curiosity. In any case, we’ve been inside Foxconn for an hour. I have no idea if the guard put out an alert when we didn’t come back from the bathroom or if anyone is looking for us or what. The sense that it’s probably best not to push it prevails, even though we haven’t made it on to a working assembly line.

A protester dressed as a factory worker outside an Apple retail outlet in Hong Kong, May 2011. Photograph: Antony Dickson/AFP/Getty Images

We head back the way we came. Before long, we find an exit. It’s pushing evening as we join a river of thousands and, heads down, shuffle through the security checkpoint. Nobody says a word. Getting out of the haunting megafactory is a relief, but the mood sticks. No, there were no child labourers with bleeding hands pleading at the windows. There were a number of things that would surely violate the US Occupational Safety and Health Administration code – unprotected construction workers, open chemical spillage, decaying, rusted structures, and so on – but there are probably a lot of things at US factories that would violate OSHA code too. Apple may well be right when it argues that these facilities are nicer than others out there. Foxconn was not our stereotypical conception of a sweatshop. But there was a different kind of ugliness. For whatever reason – the rules imposing silence on the factory floors, its pervasive reputation for tragedy or the general feeling of unpleasantness the environment itself imparts – Longhua felt heavy, even oppressively subdued.

When I look back at the photos I snapped, I can’t find one that has someone smiling in it. It does not seem like a surprise that people subjected to long hours, repetitive work and harsh management might develop psychological issues. That unease is palpable – it’s worked into the environment itself. As Xu said: “It’s not a good place for human beings.”

The sprawling factory compound, all grey dormitories and weather-beaten warehouses, blends seamlessly into the outskirts of the Shenzhen megalopolis. Foxconn’s enormous Longhua plant is a major manufacturer of Apple products. It might be the best-known factory in the world; it might also might be among the most secretive and sealed-off. Security guards man each of the entry points. Employees can’t get in without swiping an ID card; drivers entering with delivery trucks are subject to fingerprint scans. A Reuters journalist was once dragged out of a car and beaten for taking photos from outside the factory walls. The warning signs outside – “This factory area is legally established with state approval. Unauthorised trespassing is prohibited. Offenders will be sent to police for prosecution!” – are more aggressive than those outside many Chinese military compounds.

But it turns out that there’s a secret way into the heart of the infamous operation: use the bathroom. I couldn’t believe it. Thanks to a simple twist of fate and some clever perseverance by my fixer, I’d found myself deep inside so-called Foxconn City.

It’s printed on the back of every iPhone: “Designed by Apple in California Assembled in China”. US law dictates that products manufactured in China must be labelled as such and Apple’s inclusion of the phrase renders the statement uniquely illustrative of one of the planet’s starkest economic divides – the cutting edge is conceived and designed in Silicon Valley, but it is assembled by hand in China.

The vast majority of plants that produce the iPhone’s component parts and carry out the device’s final assembly are based here, in the People’s Republic, where low labour costs and a massive, highly skilled workforce have made the nation the ideal place to manufacture iPhones (and just about every other gadget). The country’s vast, unprecedented production capabilities – the US Bureau of Labor Statistics estimated that as of 2009 there were 99 million factory workers in China – have helped the nation become the world’s second largest economy. And since the first iPhone shipped, the company doing the lion’s share of the manufacturing is the Taiwanese Hon Hai Precision Industry Co, Ltd, better known by its trade name, Foxconn.

Foxconn is the single largest employer in mainland China; there are 1.3 million people on its payroll. Worldwide, among corporations, only Walmart and McDonald’s employ more. As many people work for Foxconn as live in Estonia.

An employee directs jobseekers to queue up at the Foxconn recruitment centre in Shenzhen. Photograph: David Johnson/Reuters

Today, the iPhone is made at a number of different factories around China, but for years, as it became the bestselling product in the world, it was largely assembled at Foxconn’s 1.4 square-mile flagship plant, just outside Shenzhen. The sprawling factory was once home to an estimated 450,000 workers. Today, that number is believed to be smaller, but it remains one of the biggest such operations in the world. If you know of Foxconn, there’s a good chance it’s because you’ve heard of the suicides. In 2010, Longhua assembly-line workers began killing themselves. Worker after worker threw themselves off the towering dorm buildings, sometimes in broad daylight, in tragic displays of desperation – and in protest at the work conditions inside. There were 18 reported suicide attempts that year alone and 14 confirmed deaths. Twenty more workers were talked down by Foxconn officials.

The epidemic caused a media sensation – suicides and sweatshop conditions in the House of iPhone. Suicide notes and survivors told of immense stress, long workdays and harsh managers who were prone to humiliate workers for mistakes, of unfair fines and unkept promises of benefits.

The corporate response spurred further unease: Foxconn CEO, Terry Gou, had large nets installed outside many of the buildings to catch falling bodies. The company hired counsellors and workers were made to sign pledges stating they would not attempt to kill themselves.

Steve Jobs, for his part, declared: “We’re all over that” when asked about the spate of deaths and he pointed out that the rate of suicides at Foxconn was within the national average. Critics pounced on the comment as callous, though he wasn’t technically wrong. Foxconn Longhua was so massive that it could be its own nation-state, and the suicide rate was comparable to its host country’s. The difference is that Foxconn City is a nation-state governed entirely by a corporation and one that happened to be producing one of the most profitable products on the planet.

If the boss finds any problems, they don’t scold you then. They scold you later, in front of everyone, at a meeting

A cab driver lets us out in front of the factory; boxy blue letters spell out Foxconn next to the entrance. The security guards eye us, half bored, half suspicious. My fixer, a journalist from Shanghai whom I’ll call Wang Yang, and I decide to walk the premises first and talk to workers, to see if there might be a way to get inside.

The first people we stop turn out to be a pair of former Foxconn workers.

“It’s not a good place for human beings,” says one of the young men, who goes by the name Xu. He’d worked in Longhua for about a year, until a couple of months ago, and he says the conditions inside are as bad as ever. “There is no improvement since the media coverage,” Xu says. The work is very high pressure and he and his colleagues regularly logged 12-hour shifts. Management is both aggressive and duplicitous, publicly scolding workers for being too slow and making them promises they don’t keep, he says. His friend, who worked at the factory for two years and chooses to stay anonymous, says he was promised double pay for overtime hours but got only regular pay. They paint a bleak picture of a high-pressure working environment where exploitation is routine and where depression and suicide have become normalised.

“It wouldn’t be Foxconn without people dying,” Xu says. “Every year people kill themselves. They take it as a normal thing.”

Over several visits to different iPhone assembly factories in Shenzhen and Shanghai, we interviewed dozens of workers like these. Let’s be honest: to get a truly representative sample of life at an iPhone factory would require a massive canvassing effort and the systematic and clandestine interviewing of thousands of employees. So take this for what it is: efforts to talk to often skittish, often wary and often bored workers who were coming out of the factory gates, taking a lunch break or congregating after their shifts.

A Foxconn employee in a dormitory at Longhua. The rooms are currently said to sleep eight. Photograph: Wang Yishu / Imaginechina/Camera Press

The vision of life inside an iPhone factory that emerged was varied. Some found the work tolerable; others were scathing in their criticisms; some had experienced the despair Foxconn was known for; still others had taken a job just to try to find a girlfriend. Most knew of the reports of poor conditions before joining, but they either needed the work or it didn’t bother them. Almost everywhere, people said the workforce was young and turnover was high. “Most employees last only a year,” was a common refrain. Perhaps that’s because the pace of work is widely agreed to be relentless, and the management culture is often described as cruel.

Since the iPhone is such a compact, complex machine, putting one together correctly requires sprawling assembly lines of hundreds of people who build, inspect, test and package each device. One worker said 1,700 iPhones passed through her hands every day; she was in charge of wiping a special polish on the display. That works out at about three screens a minute for 12 hours a day.

More meticulous work, like fastening chip boards and assembling back covers, was slower; these workers have a minute apiece for each iPhone. That’s still 600 to 700 iPhones a day. Failing to meet a quota or making a mistake can draw public condemnation from superiors. Workers are often expected to stay silent and may draw rebukes from their bosses for asking to use the restroom.

Xu and his friend were both walk-on recruits, though not necessarily willing ones. “They call Foxconn a fox trap,” he says. “Because it tricks a lot of people.” He says Foxconn promised them free housing but then forced them to pay exorbitantly high bills for electricity and water. The current dorms sleep eight to a room and he says they used to be 12 to a room. But Foxconn would shirk social insurance and be late or fail to pay bonuses. And many workers sign contracts that subtract a hefty penalty from their pay if they quit before a three-month introductory period.

The body-catching nets are still there. They look a bit like tarps that have blown off the things they’re meant to cover

On top of that, the work is gruelling. “You have to have mental management,” says Xu, otherwise you can get scolded by bosses in front of your peers. Instead of discussing performance privately or face to face on the line, managers would stockpile complaints until later. “When the boss comes down to inspect the work,” Xu’s friend says, “if they find any problems, they won’t scold you then. They will scold you in front of everyone in a meeting later.”

“It’s insulting and humiliating to people all the time,” his friend says. “Punish someone to make an example for everyone else. It’s systematic,” he adds. In certain cases, if a manager decides that a worker has made an especially costly mistake, the worker has to prepare a formal apology. “They must read a promise letter aloud – ‘I won’t make this mistake again’– to everyone.”

This culture of high-stress work, anxiety and humiliation contributes to widespread depression. Xu says there was another suicide a few months ago. He saw it himself. The man was a student who worked on the iPhone assembly line. “Somebody I knew, somebody I saw around the cafeteria,” he says. After being publicly scolded by a manager, he got into a quarrel. Company officials called the police, though the worker hadn’t been violent, just angry.

“He took it very personally,” Xu says, “and he couldn’t get through it.” Three days later, he jumped out of a ninth-storey window.

So why didn’t the incident get any media coverage? I ask. Xu and his friend look at each other and shrug. “Here someone dies, one day later the whole thing doesn’t exist,” his friend says. “You forget about it.”

Employees have lunch in a vast refectory at the Foxconn Longhua plant. Photograph: Wang Yishu/Imaginechina/Camera Press

‘We look at everything at these companies,” Steve Jobs said after news of the suicides broke. “Foxconn is not a sweatshop. It’s a factory – but my gosh, they have restaurants and movie theatres… but it’s a factory. But they’ve had some suicides and attempted suicides – and they have 400,000 people there. The rate is under what the US rate is, but it’s still troubling.” Apple CEO, Tim Cook, visited Longhua in 2011 and reportedly met suicide-prevention experts and top management to discuss the epidemic.

In 2012, 150 workers gathered on a rooftop and threatened to jump. They were promised improvements and talked down by management; they had, essentially, wielded the threat of killing themselves as a bargaining tool. In 2016, a smaller group did it again. Just a month before we spoke, Xu says, seven or eight workers gathered on a rooftop and threatened to jump unless they were paid the wages they were due, which had apparently been withheld. Eventually, Xu says, Foxconn agreed to pay the wages and the workers were talked down.

When I ask Xu about Apple and the iPhone, his response is swift: “We don’t blame Apple. We blame Foxconn.” When I ask the men if they would consider working at Foxconn again if the conditions improved, the response is equally blunt. “You can’t change anything,” Xu says. “It will never change.”

Wang and I set off for the main worker entrance. We wind around the perimeter, which stretches on and on – we have no idea this is barely a fraction of the factory at this point.

After walking along the perimeter for 20 minutes or so, we come to another entrance, another security checkpoint. That’s when it hits me. I have to use the bathroom. Desperately. And that gives me an idea.

There’s a bathroom in there, just a few hundred feet down a stairwell by the security point. I see the universal stick-man signage and I gesture to it. This checkpoint is much smaller, much more informal. There’s only one guard, a young man who looks bored. Wang asks something a little pleadingly in Chinese. The guard slowly shakes his head no, looks at me. The strain on my face is very, very real. She asks again – he falters for a second, then another no.

We’ll be right back, she insists, and now we’re clearly making him uncomfortable. Mostly me. He doesn’t want to deal with this. Come right back, he says. Of course, we don’t.

To my knowledge, no American journalist has been inside a Foxconn plant without permission and a tour guide, without a carefully curated visit to selected parts of the factory to demonstrate how OK things really are.

Maybe the most striking thing, beyond its size – it would take us nearly an hour to briskly walk across Longhua – is how radically different one end is from the other. It’s like a gentrified city in that regard. On the outskirts, let’s call them, there are spilt chemicals, rusting facilities and poorly overseen industrial labour. The closer you get to the city centre – remember, this is a factory – the more the quality of life, or at least the amenities and the infrastructure, improves.

‘Not a good place for human beings’: Foxconn Longhua. Photograph: Brian Merchant

As we get deeper in, surrounded by more and more people, it feels like we’re getting noticed less. The barrage of stares mutates into disinterested glances. My working theory: the plant is so vast, security so tight, that if we are inside just walking around, we must have been allowed to do so. That or nobody really gives a shit. We start trying to make our way to the G2 factory block, where we’ve been told iPhones are made. After leaving “downtown”, we begin seeing towering, monolithic factory blocks – C16, E7 and so on, many surrounded by crowds of workers.

I worry about getting too cavalier and remind myself not to push it; we’ve been inside Foxconn for almost an hour now. The crowds have been thinning out the farther away from the centre we get. Then there it is: G2. It’s identical to the factory blocks that cluster around it, that threaten to fade into the background of the smoggy static sky.

G2 looks deserted, though. A row of impossibly rusted lockers runs outside the building. No one’s around. The door is open, so we go in. To the left, there’s an entry to a massive, darkened space; we’re heading for that when someone calls out. A floor manager has just come down the stairs and he asks us what we’re doing. My translator stammers something about a meeting and the man looks confused; then he shows us the computer monitoring system he uses to oversee production on the floor. There’s no shift right now, he says, but this is how they watch.

No sign of iPhones, though. We keep walking. Outside G3, teetering stacks of black gadgets wrapped in plastic sit in front of what looks like another loading zone. A couple of workers on smartphones drift by us. We get close enough to see the gadgets through the plastic and, nope, not iPhones either. They look like Apple TVs, minus the company logo. There are probably thousands stacked here, awaiting the next step in the assembly line.

If this is indeed where iPhones and Apple TVs are made, it’s a fairly aggressively shitty place to spend long days, unless you have a penchant for damp concrete and rust. The blocks keep coming, so we keep walking. Longhua starts to feel like the dull middle of a dystopian novel, where the dread sustains but the plot doesn’t.

We could keep going, but to our left, we see what look like large housing complexes, probably the dormitories, complete with cagelike fences built out over the roof and the windows, and so we head in that direction. The closer we get to the dorms, the thicker the crowds get and the more lanyards and black glasses and faded jeans and sneakers we see. College-age kids are gathered, smoking cigarettes, crowded around picnic tables, sitting on kerbs.

And, yes, the body-catching nets are still there. Limp and sagging, they give the impression of tarps that have half blown off the things they’re supposed to cover. I think of Xu, who said: “The nets are pointless. If somebody wants to commit suicide, they will do it.”

We are drawing stares again – away from the factories, maybe folks have more time and reason to indulge their curiosity. In any case, we’ve been inside Foxconn for an hour. I have no idea if the guard put out an alert when we didn’t come back from the bathroom or if anyone is looking for us or what. The sense that it’s probably best not to push it prevails, even though we haven’t made it on to a working assembly line.

A protester dressed as a factory worker outside an Apple retail outlet in Hong Kong, May 2011. Photograph: Antony Dickson/AFP/Getty Images

We head back the way we came. Before long, we find an exit. It’s pushing evening as we join a river of thousands and, heads down, shuffle through the security checkpoint. Nobody says a word. Getting out of the haunting megafactory is a relief, but the mood sticks. No, there were no child labourers with bleeding hands pleading at the windows. There were a number of things that would surely violate the US Occupational Safety and Health Administration code – unprotected construction workers, open chemical spillage, decaying, rusted structures, and so on – but there are probably a lot of things at US factories that would violate OSHA code too. Apple may well be right when it argues that these facilities are nicer than others out there. Foxconn was not our stereotypical conception of a sweatshop. But there was a different kind of ugliness. For whatever reason – the rules imposing silence on the factory floors, its pervasive reputation for tragedy or the general feeling of unpleasantness the environment itself imparts – Longhua felt heavy, even oppressively subdued.

When I look back at the photos I snapped, I can’t find one that has someone smiling in it. It does not seem like a surprise that people subjected to long hours, repetitive work and harsh management might develop psychological issues. That unease is palpable – it’s worked into the environment itself. As Xu said: “It’s not a good place for human beings.”

Sunday, 9 October 2016

A Free Market in Tax

Nick Cohen in The Guardian

Donald Trump’s tax affairs are as nothing compared to those of the great global corporations

Keeping it offshore: Jost Van Dyke in the British Virgin Islands, a tax haven for the world’s rich. Photograph: Alamy

Donald Trump is offering himself as president of a country whose federal income taxes he gives every appearance of dodging. He says he is fit to be commander in chief, after avoiding giving a cent more than he could towards the wages of the troops who must fight for him. He laments an America where “our roads and bridges are falling apart, our airports are in third world condition and 43 million Americans are on food stamps”, while striving tirelessly to avoid paying for one pothole to be mended or mouth to be filled.

Men’s lies reveal more about them than their truths. For years, Trump promoted the bald, racist lie that Barack Obama was born in Kenya and, as an unAmerican, was disqualified from holding the presidency. We should have guessed then. We should have known that Trump’s subconscious was trying to hide the fact that he was barely an American citizen at all.

He would not contribute to his country or play his part in its collective endeavours. Like a guest in a hotel who runs off leaving the bill, Trump wanted to enjoy the room service without paying for the room. You should never lose your capacity to be shocked, especially in 2016 when the shocking has become commonplace. The New York Times published a joint piece last week by former White House ethics advisers – one to George W Bush and one to Barack Obama, so no one could accuse the paper of bias. They were stunned.

No president would have nominated Trump for public office, they said. If one had, “explaining to the senate and to the American people how a billionaire could have a $916m ‘loss carry-forward’ that potentially allowed him to not pay taxes for perhaps as long as 18 years would have been far too difficult for the White House when many hard-working Americans turn a third or more of their earnings over to the government”.

Trump’s bragging about the humiliations he inflicts on women is shocking. Trump’s oxymoronic excuses about his “fiduciary duty” to his businesses to pay as little personal tax as he could are shocking. (No businessman has a corporate “fiduciary duty” to enrich himself rather than his company.) Never let familiarity dilute your contempt.

And yet looked at from another angle, Trump is not so shocking. You may be reading this piece online after clicking on a Facebook link. If you are in Britain, the profits from the adverts Facebook hits you with will be logged in Ireland, which required Facebook to pay a mere €3.4m in corporate taxes last year on revenues of €4.83bn . If you are reading on an Apple device, Apple has booked $214.9bn offshore to avoid $65.4bn in US taxes. They are hardly alone. One recent American study found that 367 of the Fortune 500 operate one or more subsidiaries in tax havens.

Trump may seem a grotesque and alien figure, but his values are all around you. The Pepsi in your hand, the iPhone in your pocket, the Google search engine you load and the Nike trainers you put on your feet come from a tax-exempt economy, which expects you to pick up the bills.

The short answer to Conservatives who say “their behaviour is legal” is that it is a scandal that it is legal. The long answer is to invite them to look at the state of societies where Trumpian economics have taken hold. If they live in Britain or America, they should not have to look far.

The story liberal capitalism tells itself is heroic. Bloated incumbent businesses are overthrown by daring entrepreneurs. They outwit the complacent and blundering old firms and throw them from their pinnacles. They let creative destruction rip through the economy and bring new products and jobs with it.

If that justification for free-market capitalism was ever true, it is not true now. The free market in tax, it turns out, allows firms to move offshore and leave stagnant economies behind. Giant companies are no longer threatened by buccaneering entrepreneurs and innovative small businesses. Indeed, they don’t appear to be threatened by anyone.

The share of nominal GDP generated by the Fortune 100 biggest American companies rose from 33% of GDP in 1994 to 46% in 2013, the Economist reported. Despite all the fuss about tech entrepreneurship, the number of startups is lower than at any time since the late 1970s. More US companies now die than are born.

For how can small firms, which have to pay tax, challenge established giants that move their money offshore? They don’t have lobbyists. They can’t use a small part of their untaxed profits to make the campaign donations Google and the other monopolistic firms give to keep the politicians onside.

John Lewis has asked our government repeatedly how it can be fair to charge the partnership tax while allowing its rival Amazon to run its business through Luxembourg. A more pertinent question is why any government desperate for revenue would want a system that gave tax dodgers a competitive advantage.

What applies to businesses applies to individuals. The tax take depends as much on national culture as the threat of punishment, on what economists call “tax morale”.

No one likes paying taxes, but in northern European and North American countries most thought that they should pay them. Maybe I have lived a sheltered life, but I have no more heard friends discuss how they cheat the taxman than I have heard them discuss how they masturbate. If they cheat, they keep their dirty secrets to themselves. Let tax morale collapse, let belief in the integrity of the system waver, however, and states become like Greece, where everyone who can evade tax does.

The surest way to destroy morale is to make the people who pay taxes believe that the government is taking them for fools by penalising them while sparing the wealthy.

Theresa May promised at the Conservative party conference that “however rich or powerful – you have a duty to pay your tax”.

I would have been more inclined to believe her if she had promised, at this moment of asserting sovereignty, to close the British sovereign tax havens of the Channel Islands, Isle of Man, Bermuda and the British Virgin and Cayman Islands.

But let us give the new PM time to prove herself. If she falters, she should consider this. Revenue & Customs can only check 4% of self-assessment tax returns. If the remaining 96% decide that if Trump and his kind can cheat, they can cheat too, she would not be able to stop them.

Donald Trump’s tax affairs are as nothing compared to those of the great global corporations

Keeping it offshore: Jost Van Dyke in the British Virgin Islands, a tax haven for the world’s rich. Photograph: Alamy

Donald Trump is offering himself as president of a country whose federal income taxes he gives every appearance of dodging. He says he is fit to be commander in chief, after avoiding giving a cent more than he could towards the wages of the troops who must fight for him. He laments an America where “our roads and bridges are falling apart, our airports are in third world condition and 43 million Americans are on food stamps”, while striving tirelessly to avoid paying for one pothole to be mended or mouth to be filled.

Men’s lies reveal more about them than their truths. For years, Trump promoted the bald, racist lie that Barack Obama was born in Kenya and, as an unAmerican, was disqualified from holding the presidency. We should have guessed then. We should have known that Trump’s subconscious was trying to hide the fact that he was barely an American citizen at all.

He would not contribute to his country or play his part in its collective endeavours. Like a guest in a hotel who runs off leaving the bill, Trump wanted to enjoy the room service without paying for the room. You should never lose your capacity to be shocked, especially in 2016 when the shocking has become commonplace. The New York Times published a joint piece last week by former White House ethics advisers – one to George W Bush and one to Barack Obama, so no one could accuse the paper of bias. They were stunned.

No president would have nominated Trump for public office, they said. If one had, “explaining to the senate and to the American people how a billionaire could have a $916m ‘loss carry-forward’ that potentially allowed him to not pay taxes for perhaps as long as 18 years would have been far too difficult for the White House when many hard-working Americans turn a third or more of their earnings over to the government”.

Trump’s bragging about the humiliations he inflicts on women is shocking. Trump’s oxymoronic excuses about his “fiduciary duty” to his businesses to pay as little personal tax as he could are shocking. (No businessman has a corporate “fiduciary duty” to enrich himself rather than his company.) Never let familiarity dilute your contempt.

And yet looked at from another angle, Trump is not so shocking. You may be reading this piece online after clicking on a Facebook link. If you are in Britain, the profits from the adverts Facebook hits you with will be logged in Ireland, which required Facebook to pay a mere €3.4m in corporate taxes last year on revenues of €4.83bn . If you are reading on an Apple device, Apple has booked $214.9bn offshore to avoid $65.4bn in US taxes. They are hardly alone. One recent American study found that 367 of the Fortune 500 operate one or more subsidiaries in tax havens.

Trump may seem a grotesque and alien figure, but his values are all around you. The Pepsi in your hand, the iPhone in your pocket, the Google search engine you load and the Nike trainers you put on your feet come from a tax-exempt economy, which expects you to pick up the bills.

The short answer to Conservatives who say “their behaviour is legal” is that it is a scandal that it is legal. The long answer is to invite them to look at the state of societies where Trumpian economics have taken hold. If they live in Britain or America, they should not have to look far.

The story liberal capitalism tells itself is heroic. Bloated incumbent businesses are overthrown by daring entrepreneurs. They outwit the complacent and blundering old firms and throw them from their pinnacles. They let creative destruction rip through the economy and bring new products and jobs with it.

If that justification for free-market capitalism was ever true, it is not true now. The free market in tax, it turns out, allows firms to move offshore and leave stagnant economies behind. Giant companies are no longer threatened by buccaneering entrepreneurs and innovative small businesses. Indeed, they don’t appear to be threatened by anyone.

The share of nominal GDP generated by the Fortune 100 biggest American companies rose from 33% of GDP in 1994 to 46% in 2013, the Economist reported. Despite all the fuss about tech entrepreneurship, the number of startups is lower than at any time since the late 1970s. More US companies now die than are born.

For how can small firms, which have to pay tax, challenge established giants that move their money offshore? They don’t have lobbyists. They can’t use a small part of their untaxed profits to make the campaign donations Google and the other monopolistic firms give to keep the politicians onside.

John Lewis has asked our government repeatedly how it can be fair to charge the partnership tax while allowing its rival Amazon to run its business through Luxembourg. A more pertinent question is why any government desperate for revenue would want a system that gave tax dodgers a competitive advantage.

What applies to businesses applies to individuals. The tax take depends as much on national culture as the threat of punishment, on what economists call “tax morale”.

No one likes paying taxes, but in northern European and North American countries most thought that they should pay them. Maybe I have lived a sheltered life, but I have no more heard friends discuss how they cheat the taxman than I have heard them discuss how they masturbate. If they cheat, they keep their dirty secrets to themselves. Let tax morale collapse, let belief in the integrity of the system waver, however, and states become like Greece, where everyone who can evade tax does.

The surest way to destroy morale is to make the people who pay taxes believe that the government is taking them for fools by penalising them while sparing the wealthy.

Theresa May promised at the Conservative party conference that “however rich or powerful – you have a duty to pay your tax”.

I would have been more inclined to believe her if she had promised, at this moment of asserting sovereignty, to close the British sovereign tax havens of the Channel Islands, Isle of Man, Bermuda and the British Virgin and Cayman Islands.

But let us give the new PM time to prove herself. If she falters, she should consider this. Revenue & Customs can only check 4% of self-assessment tax returns. If the remaining 96% decide that if Trump and his kind can cheat, they can cheat too, she would not be able to stop them.

Tuesday, 20 September 2016

Your new iPhone’s features include oppression, inequality – and vast profit

Aditya Chakrabortty in The Guardian

Human battery hens make Apple’s devices in China. The company, which has a bigger cash pile than the US government, symbolises a broken economic system

Illustration by Andrzej Krauze

Illustration by Andrzej KrauzeSoon enough, we will see the first obituaries for openness, free trade and globalisation. When those writers ponder how wealthy countries turned towards the politics of Donald Trump and Nigel Farage, they should devote a large chapter to Apple. Because the world’s richest company is a textbook example of how the promises made after the fall of the Berlin Wall have been made a mockery of.

Whatever marvels have been shoved into the new iPhones, the devices serve to increase the gulf between the super-rich and the rest of us, bilk countries of rightful tax revenues, and oppress Chinese workers even while depriving Americans of high-paying jobs. Arrogant towards critics and governments, glutted with cash and yet plainly out of ideas, Apple is elegant shorthand for a redundant economic system.

None of this is how we’re meant to think of Apple, the multinational that is both on your side yet restlessly questing ahead. While launching the iPhone 7 this month, its marketing chief, Phil Schiller, explained why this model came without a earphone socket: “It really comes down to one word: courage. The courage to move on, do something new, that betters all of us.” Such patchouli-scented Californian dipshittery was lapped up by the 7,000-strong crowd and lightly mocked by the press – but it also helps to obscure some of the less tolerable aspect of the iPhone business model, such as the conditions in which it is made.

If you own an iPhone it was assembled by workers at one of three firms in China: Foxconn, Wistron and Pegatron. The biggest and most famous, Foxconn, came to international prominence in 2010 when an estimated 18 of its employees tried to kill themselves. At least 14 workers died. The company’s response was to put up suicide nets, to catch people trying to jump to their death. That year, staff at Foxconn’s Longhua factory made 137,000 iPhones a day, or around 90 a minute.

One of those attempted suicides, a 17-year-old called Tian Yu, flung herself from the fourth floor of a factory dormitory and ended up paralysed from the waist down. Speaking later to academic researchers, she described her working conditions in remarkable testimony that I then covered for the Guardian. She was essentially a human battery hen, working over 12 hours a day, six days a week, swapped between day and night shifts and kept in an eight-person dorm room.

After the scandals of 2010, Apple vowed to improve conditions for its Chinese workers. It has since published a number of glossy brochures extolling its commitments to them. Yet there is no evidence that the Californian firm has given back a single penny of its gigantic profit margins to its contractors to ensure better treatment of the people who actually make its products.

Over the past year, the US-based NGO China Labor Watch has published a series ofinvestigations into Pegatron, another iPhone assembler. It sent a researcher on to the assembly line, interviewed dozens of Pegatron staff and analysed hundreds of pay stubs. Among its findings are that staff still work 12 hours a day, six days a week – one and a half hours of that unpaid. They are forced to do overtime, claims the NGO, and provided with illegally low levels of safety training.

The researcher was working on one iPhone motherboard every 3.75 seconds, standing up for the entirety of his 10.5-hour shift. Such is the punishment endured at Apple’s contractors to make a living wage, apparently.

FacebookTwitterPinterest Tim Cook with dancer Maddie Ziegler. The Apple CEO ‘rejects a €13bn tax bill from the EU as ‘political crap’’. Photograph: Josh Edelson/AFP/Getty Images

The Shanghai local government has raised the minimum wage over the past year; Pegatron has responded by cutting subsidies on things such as medical insurance so that the effective hourly pay for its staff has fallen.

When questioned about these reports, Pegatron provided a statement that read in part: “We work hard to make sure every Pegatron facility provides a healthy work environment and allegations suggesting otherwise are simply not true … We have taken effective measures … to ensure employees do not work more than 60 hours per week and six days per week.”

At another of Apple’s major contractors, Wistron, a Danish human-rights NGO last year found extensive evidence of forced student labour. Teenagers doing degrees in accountancy or business management were sent for months to an assembly line at Wistron. This is a serious violation of International Labour Organisationconvention, yet investigators for Danwatch found evidence that thousands of students were doing the same work and backbreaking hours there as the adults – but costing less.

The teenagers told Danwatch that they were working against their will. “We are all depressed,” one 19-year-old girl said. “But we have no choice, because the school told us that if we refused, we would not get our diploma.” Despite several requests for comment, Wistron did not respond.

That investigation was not at a factory making iPhones, but Apple confirmed that Wistron and Pegatron were two of their major assemblers in China. While it did not wish to say anything on the record, Apple’s press officers pointed me to the audits it had commissioned into its supplier factories. Yet the inspections are almost conveniently skimpy.

Look at the report Apple commissioned into Foxconn in 2012, after those suicide attempts. Foxconn is the largest private employer in China, with around 400,000 workers at the Longhua factory alone. Yet the report for Apple, complementary to an investigation already being carried out by the Fair Labor Association, admits to looking at just three of those plants for three days apiece. Jenny Chan, one of the foremost scholars of Chinese labour abuses and co-author of the forthcomingDying for an iPhone, calls it “parachute auditing – a way to allow ‘business as usual’ to carry on”. A very profitable way, as it happens. While iPhone workers for Pegatron saw their hourly pay drop to just $1.60 an hour, Apple remained the most profitable big company in America, pulling in over $47bn in profit in 2015 alone.

What does this add up to? At $231bn, Apple has a bigger cash pile than the US government, but apparently won’t spend even a sliver on improving conditions for those who actually make its money. Nor will it make those iPhones in America, which would create jobs and still leave it as the most profitable smartphone in the world.

It would rather accrue more profits, to go to those who hold Apple stock – such as company boss Tim Cook, whose hoard of company shares is worth $785m. Friends of Cook point to his philanthropy, but while he’s happy to spend on pet projects, he rejects a €13bn tax bill from the EU as “political crap” – whileboasting about how he won’t bring Apple’s billions back to the US “until there’s a fair rate … It doesn’t go that the more you pay, the more patriotic you are.” The tech oligarch seems to think he knows better than 300 million Americans what tax rates their elected government should set.

When the historians of globalisation ask why it died, they will surely find that companies such as Apple form a large part of the answer. Faced with a binary choice between an economic model that lavishly rewarded a few and a populism that makes lavish promises to many, between Cook on the one hand and Farage on the other, the voters went for the one who at least didn’t bang on about “courage”.

Wednesday, 30 March 2016

Apple v FBI - Some Uncomfortable Truths

‘We must not lose sight of corporate power.’ Grand Central, an installation by Valentin Ruhry, cleverly subverts digital consumer culture with a product display featuring everyday objects found at a train station. MAK GALLERY, Vienna, 2014, curated by Marlies Wirth. Courtesy of Christine König Galerie, Vienna.

Julia Powles and Enrique Chaparro in The Guardian

It has been a spectacular six-week showdown – the world’s most valuable brand, Apple, pitted against the powerful American agents of the FBI. Two titans of spin, locked in a fast-moving battle over a dead terrorist’s smartphone. Now, as dramatically as it exploded, the FBI’s legal demand that Apple help it crack the iPhone of one of the San Bernardino killers has evaporated – the agents hacked their way in anyway, assisted by a mysterious third party.

There was always more to the Apple v FBI case than met the eye – and it is true for this latest twist too. The biggest issue is that both sides stand to gain a lot more from this battle than any of us. With little relation to reality, and backed by a worryingly partisan chorus, the notoriously closed Apple is emerging as a champion of users’ rights. Equally worryingly, a government agency is claiming the power to keep to itself a tool that can potentially break security features on millions of phones, while earmarking a demand for further judicial or legislative intervention in the future. Whichever way you look, this feud is far from a road to freedom in the digital environment.

Julia Powles and Enrique Chaparro in The Guardian

It has been a spectacular six-week showdown – the world’s most valuable brand, Apple, pitted against the powerful American agents of the FBI. Two titans of spin, locked in a fast-moving battle over a dead terrorist’s smartphone. Now, as dramatically as it exploded, the FBI’s legal demand that Apple help it crack the iPhone of one of the San Bernardino killers has evaporated – the agents hacked their way in anyway, assisted by a mysterious third party.

There was always more to the Apple v FBI case than met the eye – and it is true for this latest twist too. The biggest issue is that both sides stand to gain a lot more from this battle than any of us. With little relation to reality, and backed by a worryingly partisan chorus, the notoriously closed Apple is emerging as a champion of users’ rights. Equally worryingly, a government agency is claiming the power to keep to itself a tool that can potentially break security features on millions of phones, while earmarking a demand for further judicial or legislative intervention in the future. Whichever way you look, this feud is far from a road to freedom in the digital environment.

Breaching Fortress Apple

From the FBI’s side, it seems clear that the case was opportunistically selected. No one wants to defend a terrorist. And after hammering on about law enforcement “going dark” on secured communications, the authorities were salivating for a pin-up case. Terror on home soil provided it.

But the FBI failed to account for one thing: the fallout of enraging a cultish brand on top of the most guarded, controlling ecosystem that computing has ever seen. Apple, incensed at the idea of anyone trespassing on its authority, went public – an equally opportunistic move, straight from the Taylor Swift playbook. And in so doing, Apple debunked the FBI’s otherwise earnest rhetoric that it only wanted to get at one iPhone, from one terrorist.

The key fact is that the FBI demanded a general tool: a modified operating system able to circumvent certain user-set security features in any given iPhone. There are clear dangers in bringing such a tool into existence. As forensics expert Jonathan Ździarski puts it, this is “a bomb on a leash”; a leash that can be undone, legally or otherwise. The FBI’s last-minute deferral of the court hearing in this case would, ideally, have been the enlightened recognition of this reality, as well as the multiple case-handling incompetencies and dubious legal foundations of the FBI’s request. Bizarrely, the withdrawal was on another ground: a third party had emerged with a hack. With the case now wholly dropped, we have a new danger: a classified bomb held by the FBI and unknown third-party hackers – but not by Apple, the one party capable of defusing it.

These facts are as much as the public debate has countenanced, resulting in predictable mud-slinging between techies and bureaucrats; big tech and big brother. What this misses is that this case has been a cause célèbre all along because it presents minimal threat to vested interests and power.

Apple v FBI was never the mother of all privacy battles. It is and always has been a security battle, between alleged national security and individual security, fought over a landscape of increasing insecurity.

It is this insecurity – existing, pervasive, worsening, global vulnerability of our infrastructure, communications and rights – that has been the greatest deception in this battle to date. Because despite how Apple has portrayed itself and been valorized by the media, phones are not impregnable, nor are our data and the platforms they reside on. Not by a long shot. The outside hack proves just that: if an external source that decided to cooperate with the FBI could break into the phone, and in shockingly short time, other less savory sources could do so too.

This case should be a tremendous opportunity for a global conversation about technology fragility. We need responsible leadership that recognizes that there is no such thing as perfect security, and that responds with restraint and redundancy, rather than a headlong tumble into connecting all the things.

Coupled to this must be a specific concession at the heart of the case and the unsatisfactory truce now reached. Digital locks and picks, by their very nature, are binary – they work for all or for none. In the current state of the art, it isimpossible to manufacture what the FBI wants: implanted vulnerabilities, or “backdoors”, that work exclusively for “good guys with a warrant”. Whatever the FBI is holding now, it suffers from this reality. But the problem is also bigger than that. As renowned computer security expert Matt Blaze describes the essence of the dilemma: “We can’t discuss how to make our systems secure with backdoors until we can figure out how to do it without backdoors.”

Boxing in the shadows of vast corporate power

This case, and others like it, are also an opportunity for a deep and reaching conversation about corporate power, and about the increasing intrusion of tech majors into democratic space. This is an angle that has been worryingly absent in most of the case’s commentary.

Regardless of the merits of its position, many of the arguments that have been marshaled at Apple’s feet in recent weeks set a dangerous, potentially pernicious trend. In particular, the argument that corporations are subjects entitled to human rights such as freedom of expression is deeply problematic, undermining reasonable regulation and presenting a destabilizing influence on democracy. The black box society is real, and this case and inevitable future iterations of the same battle have every indication of making it worse.

So we are at the crossroads. And out in the cold. Many decisive questions still remain open, and despite the reams of technical jargon written about this case, its core is not primarily technical, but political.

Under ideal circumstances, and privilege against self-incrimination aside, we should expect that any society would reasonably cooperate with law enforcement to investigate heinous crimes. But what is the most rational response to take when authorities such as the FBI, as well as lawmakers around the world,continue to overreach in their demands, seemingly unwilling to protect an already fragile technology ecosystem and our rights within it?