'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label facebook. Show all posts

Showing posts with label facebook. Show all posts

Thursday, 10 June 2021

Thursday, 14 January 2021

Thursday, 2 July 2020

What's wrong with WhatsApp

As social media has become more inhospitable, the appeal of private online groups has grown. But they hold their own dangers – to those both inside and out. By William Davies in The Guardian

In the spring, as the virus swept across the world and billions of people were compelled to stay at home, the popularity of one social media app rose more sharply than any other. By late March, usage of WhatsApp around the world had grown by 40%. In Spain, where the lockdown was particularly strict, it rose by 76%. In those early months, WhatsApp – which hovers neatly between the space of email, Facebook and SMS, allowing text messages, links and photos to be shared between groups – was a prime conduit through which waves of news, memes and mass anxiety travelled.

At first, many of the new uses were heartening. Mutual aid groups sprung up to help the vulnerable. Families and friends used the app to stay close, sharing their fears and concerns in real time. Yet by mid-April, the role that WhatsApp was playing in the pandemic looked somewhat darker. A conspiracy theory about the rollout of 5G, which originated long before Covid-19 had appeared, now claimed that mobile phone masts were responsible for the disease. Across the UK, people began setting fire to 5G masts, with 20 arson attacks over the Easter weekend alone.

WhatsApp, along with Facebook and YouTube, was a key channel through which the conspiracy theory proliferated. Some feared that the very same community groups created during March were now accelerating the spread of the 5G conspiracy theory. Meanwhile, the app was also enabling the spread of fake audio clips, such as a widely shared recording in which someone who claimed to work for the NHS reported that ambulances would no longer be sent to assist people with breathing difficulties.

This was not the first time that WhatsApp has been embroiled in controversy. While the “fake news” scandals surrounding the 2016 electoral upsets in the UK and US were more focused upon Facebook – which owns WhatsApp – subsequent electoral victories for Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil and Narendra Modi in India were aided by incendiary WhatsApp messaging, exploiting the vast reach of the app in these countries. In India, there have also been reports of riots and at least 30 deaths linked to rumours circulating on WhatsApp. India’s Ministry of Information and Broadcasting has sought ways of regulating WhatsApp content, though this has led to new controversies about government infringement on civil liberties.

FacebookTwitterPinterest A security message on WhatsApp. Photograph: Thomas White/Reuters

But what makes WhatsApp potentially more dangerous than public social media are the higher levels of trust and honesty that are often present in private groups. It is a truism that nobody is as happy as they appear on Facebook, as attractive as they appear on Instagram or as angry as they appear on Twitter, which spawns a growing weariness with such endless performance. By contrast, closed groups are where people take off their public masks and let their critical guard down. Neither anonymity (a precondition of most trolling) nor celebrity are on offer. The speed with which rumours circulate on WhatsApp is partly a reflection of how altruistic and uncritical people can be in groups. Most of the time, people seem to share false theories about Covid-19 not with the intention of doing harm, but precisely out of concern for other group members. Anti-vaxx, anti-5G or anti-Hillary rumours combine an identification of an enemy with a strong internal sense of solidarity. Nevertheless, they add to the sense that the world is hostile and dangerous.

There is one particular pattern of a group chat that can manufacture threats and injustices out of thin air. It tends to start with one participant speculating that they are being let down or targeted by some institution or rival group – be it a public service, business or cultural community – whereupon a second participant agrees. By this stage, it becomes risky for anyone else to defend the institution or group in question, and immediately a new enemy and a new resentment is born. Instantly, the warnings and denunciations emanating from within the group take on a level of authenticity that cannot be matched by the entity that is now the object of derision.

But what if the first contributor has misunderstood or misread something, or had a very stressful day and needs to let off steam? And what if the second is merely agreeing so as to make the first one feel better? And what if the other members are either too distracted, too inhibited or too exhausted to say anything to oppose this fresh indignation? This needn’t snowball into the forms of conspiracy theory that produce riots or arson attacks. But even in milder forms, it makes the job of communicating official information – occasionally life-saving information – far more troublesome than it was just a decade ago. Information about public services and health risks is increasingly having to penetrate a thicket of overlapping groups, many of which may have developed an instinctive scepticism to anything emanating from the “mainstream”.

Part of the challenge for institutions is that there is often a strange emotional comfort in the shared feeling of alienation and passivity. “We were never informed about that”, “nobody consulted us”, “we are being ignored”. These are dominant expressions of our political zeitgeist. As WhatsApp has become an increasingly common way of encountering information and news, a vicious circle can ensue: the public world seems ever more distant, impersonal and fake, and the private group becomes a space of sympathy and authenticity.

This is a new twist in the evolution of the social internet. Since the 90s, the internet has held out a promise of connectivity, openness and inclusion, only to then confront inevitable threats to privacy, security and identity. By contrast, groups make people feel secure and anchored, but also help to fragment civil society into separate cliques, unknown to one another. This is the outcome of more than 20 years of ideological battles over what sort of social space the internet should be.

For a few years at the dawn of the millennium, the O’Reilly Emerging Technology Conferences (or ETech), were a crucible in which a new digital world was imagined and debated. Launched by the west coast media entrepreneur Tim O’Reilly and hosted annually around California, the conferences attracted a mixture of geeks, gurus, designers and entrepreneurs, brought together more in a spirit of curiosity than of commerce. In 2005, O’Reilly coined the term “web 2.0” to describe a new wave of websites that connected users with each other, rather than with existing offline institutions. Later that year, the domain name facebook.com was purchased by a 21-year-old Harvard student, and the age of the giant social media platforms was born.

Within this short window of time, we can see competing ideas of what a desirable online community might look like. The more idealistic tech gurus who attended ETech insisted that the internet should remain an open public space, albeit one in which select communities could cluster for their own particular purposes, such as creating open-source software projects or Wikipedia entries. The untapped potential of the internet, they believed, was for greater democracy. But for companies such as Facebook, the internet presented an opportunity to collect data about users en masse. The internet’s potential was for greater surveillance. The rise of the giant platforms from 2005 onwards suggested the latter view had won out. And yet, in a strange twist, we are now witnessing a revival of anarchic, self-organising digital groups – only now, in the hands of Facebook as well. The two competing visions have collided.

In the spring, as the virus swept across the world and billions of people were compelled to stay at home, the popularity of one social media app rose more sharply than any other. By late March, usage of WhatsApp around the world had grown by 40%. In Spain, where the lockdown was particularly strict, it rose by 76%. In those early months, WhatsApp – which hovers neatly between the space of email, Facebook and SMS, allowing text messages, links and photos to be shared between groups – was a prime conduit through which waves of news, memes and mass anxiety travelled.

At first, many of the new uses were heartening. Mutual aid groups sprung up to help the vulnerable. Families and friends used the app to stay close, sharing their fears and concerns in real time. Yet by mid-April, the role that WhatsApp was playing in the pandemic looked somewhat darker. A conspiracy theory about the rollout of 5G, which originated long before Covid-19 had appeared, now claimed that mobile phone masts were responsible for the disease. Across the UK, people began setting fire to 5G masts, with 20 arson attacks over the Easter weekend alone.

WhatsApp, along with Facebook and YouTube, was a key channel through which the conspiracy theory proliferated. Some feared that the very same community groups created during March were now accelerating the spread of the 5G conspiracy theory. Meanwhile, the app was also enabling the spread of fake audio clips, such as a widely shared recording in which someone who claimed to work for the NHS reported that ambulances would no longer be sent to assist people with breathing difficulties.

This was not the first time that WhatsApp has been embroiled in controversy. While the “fake news” scandals surrounding the 2016 electoral upsets in the UK and US were more focused upon Facebook – which owns WhatsApp – subsequent electoral victories for Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil and Narendra Modi in India were aided by incendiary WhatsApp messaging, exploiting the vast reach of the app in these countries. In India, there have also been reports of riots and at least 30 deaths linked to rumours circulating on WhatsApp. India’s Ministry of Information and Broadcasting has sought ways of regulating WhatsApp content, though this has led to new controversies about government infringement on civil liberties.

Brazil’s president Jair Bolsonaro with a printout of an opponent’s WhatsApp message about him. Photograph: Ueslei Marcelino/Reuters

As ever, there is a risk of pinning too much blame for complex political crises on an inert technology. WhatsApp has also taken some steps to limit its use as a vehicle for misinformation. In March, a WhatsApp spokesperson told the Washington Post that the company had “engaged health ministries around the world to provide simple ways for citizens to receive accurate information about the virus”. But even away from such visible disruptions, WhatsApp does seem to be an unusually effective vehicle for sowing distrust in public institutions and processes.

A WhatsApp group can exist without anyone outside the group knowing of its existence, who its members are or what is being shared, while end-to-end encryption makes it immune to surveillance. Back in Britain’s pre-Covid-19 days, when Brexit and Jeremy Corbyn were the issues that provoked the most feverish political discussions, speculation and paranoia swirled around such groups. Media commentators who defended Corbyn were often accused of belonging to a WhatsApp group of “outriders”, co-ordinated by Corbyn’s office, which supposedly told them what line to take. Meanwhile, the Conservative party’s pro-Brexit European Research Group was said to be chiefly sustained in the form of a WhatsApp group, whose membership was never public. Secretive coordination – both real and imagined – does not strengthen confidence in democracy.

WhatsApp groups can not only breed suspicion among the public, but also manufacture a mood of suspicion among their own participants. As also demonstrated by closed Facebook groups, discontents – not always well-founded – accumulate in private before boiling over in public. The capacity to circulate misinformation and allegations is becoming greater than the capacity to resolve them.

The political threat of WhatsApp is the flipside of its psychological appeal. Unlike so many other social media platforms, WhatsApp is built to secure privacy. On the plus side, this means intimacy with those we care about and an ability to speak freely; on the negative side, it injects an ethos of secrecy and suspicion into the public sphere. As Facebook, Twitter and Instagram become increasingly theatrical – every gesture geared to impress an audience or deflect criticism – WhatsApp has become a sanctuary from a confusing and untrustworthy world, where users can speak more frankly. As trust in groups grows, so it is withdrawn from public institutions and officials. A new common sense develops, founded on instinctive suspicion towards the world beyond the group.

The ongoing rise of WhatsApp, and its challenge to both legacy institutions and open social media, poses a profound political question: how do public institutions and discussions retain legitimacy and trust once people are organised into closed and invisible communities? The risk is that a vicious circle ensues, in which private groups circulate ever more information and disinformation to discredit public officials and public information, and our alienation from democracy escalates.

When WhatsApp was bought by Facebook in 2014 for $19bn, it was the most valuable tech acquisition in history. At the time, WhatsApp brought 450 million users with it. In February this year, it hit 2 billion users worldwide – and that is even before its lockdown surge – making it by far the most widely used messenger app, and the second most commonly used app after Facebook itself. In many countries, it is now the default means of digital communication and social coordination, especially among younger people.

The features that would later allow WhatsApp to become a conduit for conspiracy theory and political conflict were ones never integral to SMS, and have more in common with email: the creation of groups and the ability to forward messages. The ability to forward messages from one group to another – recently limited in response to Covid-19-related misinformation – makes for a potent informational weapon. Groups were initially limited in size to 100 people, but this was later increased to 256. That’s small enough to feel exclusive, but if 256 people forward a message on to another 256 people, 65,536 will have received it.

Groups originate for all sorts of purposes – a party, organising amateur sport, a shared interest – but then take on a life of their own. There can be an anarchic playfulness about this, as a group takes on its own set of in-jokes and traditions. In a New York Magazine piece last year, under the headline “Group chats are making the internet fun again”, the technology critic Max Read argued that groups have become “an outright replacement for the defining mode of social organization of the past decade: the platform-centric, feed-based social network.”

It’s understandable that in order to relax, users need to know they’re not being overheard – though there is a less playful side to this. If groups are perceived as a place to say what you really think, away from the constraints of public judgement or “political correctness”, then it follows that they are also where people turn to share prejudices or more hateful expressions, that are unacceptable (or even illegal) elsewhere. Santiago Abascal, the leader of the Spanish far-right party Vox, has defined his party as one willing to “defend what Spaniards say on WhatsApp”.

As ever, there is a risk of pinning too much blame for complex political crises on an inert technology. WhatsApp has also taken some steps to limit its use as a vehicle for misinformation. In March, a WhatsApp spokesperson told the Washington Post that the company had “engaged health ministries around the world to provide simple ways for citizens to receive accurate information about the virus”. But even away from such visible disruptions, WhatsApp does seem to be an unusually effective vehicle for sowing distrust in public institutions and processes.

A WhatsApp group can exist without anyone outside the group knowing of its existence, who its members are or what is being shared, while end-to-end encryption makes it immune to surveillance. Back in Britain’s pre-Covid-19 days, when Brexit and Jeremy Corbyn were the issues that provoked the most feverish political discussions, speculation and paranoia swirled around such groups. Media commentators who defended Corbyn were often accused of belonging to a WhatsApp group of “outriders”, co-ordinated by Corbyn’s office, which supposedly told them what line to take. Meanwhile, the Conservative party’s pro-Brexit European Research Group was said to be chiefly sustained in the form of a WhatsApp group, whose membership was never public. Secretive coordination – both real and imagined – does not strengthen confidence in democracy.

WhatsApp groups can not only breed suspicion among the public, but also manufacture a mood of suspicion among their own participants. As also demonstrated by closed Facebook groups, discontents – not always well-founded – accumulate in private before boiling over in public. The capacity to circulate misinformation and allegations is becoming greater than the capacity to resolve them.

The political threat of WhatsApp is the flipside of its psychological appeal. Unlike so many other social media platforms, WhatsApp is built to secure privacy. On the plus side, this means intimacy with those we care about and an ability to speak freely; on the negative side, it injects an ethos of secrecy and suspicion into the public sphere. As Facebook, Twitter and Instagram become increasingly theatrical – every gesture geared to impress an audience or deflect criticism – WhatsApp has become a sanctuary from a confusing and untrustworthy world, where users can speak more frankly. As trust in groups grows, so it is withdrawn from public institutions and officials. A new common sense develops, founded on instinctive suspicion towards the world beyond the group.

The ongoing rise of WhatsApp, and its challenge to both legacy institutions and open social media, poses a profound political question: how do public institutions and discussions retain legitimacy and trust once people are organised into closed and invisible communities? The risk is that a vicious circle ensues, in which private groups circulate ever more information and disinformation to discredit public officials and public information, and our alienation from democracy escalates.

When WhatsApp was bought by Facebook in 2014 for $19bn, it was the most valuable tech acquisition in history. At the time, WhatsApp brought 450 million users with it. In February this year, it hit 2 billion users worldwide – and that is even before its lockdown surge – making it by far the most widely used messenger app, and the second most commonly used app after Facebook itself. In many countries, it is now the default means of digital communication and social coordination, especially among younger people.

The features that would later allow WhatsApp to become a conduit for conspiracy theory and political conflict were ones never integral to SMS, and have more in common with email: the creation of groups and the ability to forward messages. The ability to forward messages from one group to another – recently limited in response to Covid-19-related misinformation – makes for a potent informational weapon. Groups were initially limited in size to 100 people, but this was later increased to 256. That’s small enough to feel exclusive, but if 256 people forward a message on to another 256 people, 65,536 will have received it.

Groups originate for all sorts of purposes – a party, organising amateur sport, a shared interest – but then take on a life of their own. There can be an anarchic playfulness about this, as a group takes on its own set of in-jokes and traditions. In a New York Magazine piece last year, under the headline “Group chats are making the internet fun again”, the technology critic Max Read argued that groups have become “an outright replacement for the defining mode of social organization of the past decade: the platform-centric, feed-based social network.”

It’s understandable that in order to relax, users need to know they’re not being overheard – though there is a less playful side to this. If groups are perceived as a place to say what you really think, away from the constraints of public judgement or “political correctness”, then it follows that they are also where people turn to share prejudices or more hateful expressions, that are unacceptable (or even illegal) elsewhere. Santiago Abascal, the leader of the Spanish far-right party Vox, has defined his party as one willing to “defend what Spaniards say on WhatsApp”.

A WhatsApp newspaper ad in India warning about fake information on its service. Photograph: Prakash Singh/AFP/Getty Images

A different type of group emerges where its members are all users of the same service, such as a school, a housing block or a training programme. A potential problem here is one of negative solidarity, in which feelings of community are deepened by turning against the service in question. Groups of this sort typically start from a desire to pool information – students staying in touch about deadlines, say – but can swiftly become a means of discrediting the institution they cluster around. Initial murmurs of dissatisfaction can escalate rapidly, until the group has forged an identity around a spirit of resentment and alienation, which can then be impossible to dislodge with countervailing evidence.

Faced with the rise of new technologies, one option for formal organisations and associations is to follow people to their preferred platform. In March, the government introduced a WhatsApp-based information service about Covid-19, with an automated chatbot. But groups themselves can be an unreliable means of getting crucial information to people. Anecdotal evidence from local political organisers and trade union reps suggests that, despite the initial efficiency of WhatsApp groups, their workload often increases because of the escalating number of sub-communities, each of which needs to be contacted separately. Schools desperately seek to get information out to parents, only to discover that unless it appears in precisely the right WhatsApp group, it doesn’t register. The age of the message board, be it physical or digital, where information can be posted once for anyone who needs it, is over.

WhatsApp’s ‘broadcast list’ function, which allows messages to be sent to multiple recipients who are invisible to one another (like email’s ‘bcc’ line), alleviates some of the problems of groups taking on a life of their own. But even then, lists can only include people who are already mutual contacts of the list-owner. The problem, from the point of view of institutions, is that WhatsApp use seems fuelled by a preference for informal, private communication as such. University lecturers are frequently baffled by the discovery that many students and applicants don’t read email. If email is going into decline, WhatsApp does not seem to be a viable alternative when it comes to sharing verified information as widely and inclusively as possible.

Groups are great for brief bursts of humour or frustration, but, by their very nature, far less useful for supporting the circulation of public information. To understand why this is the case, we have to think about the way in which individuals can become swayed and influenced once they belong to a group.

The internet has brought with it its own litany of social pathologies and threats. Trolling, flaming, doxing, cancelling and pile-ons are all risks that go with socialising within a vast open architecture. “Open” platforms such as Twitter are reminders that much social activity tends to be aimed at a small and select community, but can be rendered comical or shameful when exposed to a different community altogether.

As any frequent user of WhatsApp or a closed Facebook group will recognise, the moral anxiety associated with groups is rather different. If the worry in an open network is of being judged by some outside observer, be it one’s boss or an extended family member, in a closed group it is of saying something that goes against the codes that anchor the group’s identity. Groups can rapidly become dominated by a certain tone or worldview that is uncomfortable to challenge and nigh-impossible to dislodge. WhatsApp is a machine for generating feelings of faux pas, as comments linger in a group’s feed, waiting for a response.

This means that while groups can generate high levels of solidarity, which can in principle be put to powerful political effect, it also becomes harder to express disagreement within the group. If, for example, an outspoken and popular member of a neighbourhood WhatsApp group begins to circulate misinformation about health risks, the general urge to maintain solidarity means that their messages are likely to be met with approval and thanks. When a claim or piece of content shows up in a group, there may be many members who view it as dubious; the question is whether they have the confidence to say as much. Meanwhile, the less sceptical can simply forward it on. It’s not hard, then, to understand why WhatsApp is a powerful distributor of “fake news” and conspiracy theories.

As on open social platforms, one of the chief ways of building solidarity on WhatsApp is to posit some injustice or enemy that threatens the group and its members. In the most acute examples, conspiracy theories are unleashed against political opponents, to the effect that they are paedophiles or secret affiliates of foreign powers. Such plausibly deniable practices swirled around the fringes of the successful election campaigns of Modi, Bolsonaro and Donald Trump, and across multiple platforms.

A different type of group emerges where its members are all users of the same service, such as a school, a housing block or a training programme. A potential problem here is one of negative solidarity, in which feelings of community are deepened by turning against the service in question. Groups of this sort typically start from a desire to pool information – students staying in touch about deadlines, say – but can swiftly become a means of discrediting the institution they cluster around. Initial murmurs of dissatisfaction can escalate rapidly, until the group has forged an identity around a spirit of resentment and alienation, which can then be impossible to dislodge with countervailing evidence.

Faced with the rise of new technologies, one option for formal organisations and associations is to follow people to their preferred platform. In March, the government introduced a WhatsApp-based information service about Covid-19, with an automated chatbot. But groups themselves can be an unreliable means of getting crucial information to people. Anecdotal evidence from local political organisers and trade union reps suggests that, despite the initial efficiency of WhatsApp groups, their workload often increases because of the escalating number of sub-communities, each of which needs to be contacted separately. Schools desperately seek to get information out to parents, only to discover that unless it appears in precisely the right WhatsApp group, it doesn’t register. The age of the message board, be it physical or digital, where information can be posted once for anyone who needs it, is over.

WhatsApp’s ‘broadcast list’ function, which allows messages to be sent to multiple recipients who are invisible to one another (like email’s ‘bcc’ line), alleviates some of the problems of groups taking on a life of their own. But even then, lists can only include people who are already mutual contacts of the list-owner. The problem, from the point of view of institutions, is that WhatsApp use seems fuelled by a preference for informal, private communication as such. University lecturers are frequently baffled by the discovery that many students and applicants don’t read email. If email is going into decline, WhatsApp does not seem to be a viable alternative when it comes to sharing verified information as widely and inclusively as possible.

Groups are great for brief bursts of humour or frustration, but, by their very nature, far less useful for supporting the circulation of public information. To understand why this is the case, we have to think about the way in which individuals can become swayed and influenced once they belong to a group.

The internet has brought with it its own litany of social pathologies and threats. Trolling, flaming, doxing, cancelling and pile-ons are all risks that go with socialising within a vast open architecture. “Open” platforms such as Twitter are reminders that much social activity tends to be aimed at a small and select community, but can be rendered comical or shameful when exposed to a different community altogether.

As any frequent user of WhatsApp or a closed Facebook group will recognise, the moral anxiety associated with groups is rather different. If the worry in an open network is of being judged by some outside observer, be it one’s boss or an extended family member, in a closed group it is of saying something that goes against the codes that anchor the group’s identity. Groups can rapidly become dominated by a certain tone or worldview that is uncomfortable to challenge and nigh-impossible to dislodge. WhatsApp is a machine for generating feelings of faux pas, as comments linger in a group’s feed, waiting for a response.

This means that while groups can generate high levels of solidarity, which can in principle be put to powerful political effect, it also becomes harder to express disagreement within the group. If, for example, an outspoken and popular member of a neighbourhood WhatsApp group begins to circulate misinformation about health risks, the general urge to maintain solidarity means that their messages are likely to be met with approval and thanks. When a claim or piece of content shows up in a group, there may be many members who view it as dubious; the question is whether they have the confidence to say as much. Meanwhile, the less sceptical can simply forward it on. It’s not hard, then, to understand why WhatsApp is a powerful distributor of “fake news” and conspiracy theories.

As on open social platforms, one of the chief ways of building solidarity on WhatsApp is to posit some injustice or enemy that threatens the group and its members. In the most acute examples, conspiracy theories are unleashed against political opponents, to the effect that they are paedophiles or secret affiliates of foreign powers. Such plausibly deniable practices swirled around the fringes of the successful election campaigns of Modi, Bolsonaro and Donald Trump, and across multiple platforms.

FacebookTwitterPinterest A security message on WhatsApp. Photograph: Thomas White/Reuters

But what makes WhatsApp potentially more dangerous than public social media are the higher levels of trust and honesty that are often present in private groups. It is a truism that nobody is as happy as they appear on Facebook, as attractive as they appear on Instagram or as angry as they appear on Twitter, which spawns a growing weariness with such endless performance. By contrast, closed groups are where people take off their public masks and let their critical guard down. Neither anonymity (a precondition of most trolling) nor celebrity are on offer. The speed with which rumours circulate on WhatsApp is partly a reflection of how altruistic and uncritical people can be in groups. Most of the time, people seem to share false theories about Covid-19 not with the intention of doing harm, but precisely out of concern for other group members. Anti-vaxx, anti-5G or anti-Hillary rumours combine an identification of an enemy with a strong internal sense of solidarity. Nevertheless, they add to the sense that the world is hostile and dangerous.

There is one particular pattern of a group chat that can manufacture threats and injustices out of thin air. It tends to start with one participant speculating that they are being let down or targeted by some institution or rival group – be it a public service, business or cultural community – whereupon a second participant agrees. By this stage, it becomes risky for anyone else to defend the institution or group in question, and immediately a new enemy and a new resentment is born. Instantly, the warnings and denunciations emanating from within the group take on a level of authenticity that cannot be matched by the entity that is now the object of derision.

But what if the first contributor has misunderstood or misread something, or had a very stressful day and needs to let off steam? And what if the second is merely agreeing so as to make the first one feel better? And what if the other members are either too distracted, too inhibited or too exhausted to say anything to oppose this fresh indignation? This needn’t snowball into the forms of conspiracy theory that produce riots or arson attacks. But even in milder forms, it makes the job of communicating official information – occasionally life-saving information – far more troublesome than it was just a decade ago. Information about public services and health risks is increasingly having to penetrate a thicket of overlapping groups, many of which may have developed an instinctive scepticism to anything emanating from the “mainstream”.

Part of the challenge for institutions is that there is often a strange emotional comfort in the shared feeling of alienation and passivity. “We were never informed about that”, “nobody consulted us”, “we are being ignored”. These are dominant expressions of our political zeitgeist. As WhatsApp has become an increasingly common way of encountering information and news, a vicious circle can ensue: the public world seems ever more distant, impersonal and fake, and the private group becomes a space of sympathy and authenticity.

This is a new twist in the evolution of the social internet. Since the 90s, the internet has held out a promise of connectivity, openness and inclusion, only to then confront inevitable threats to privacy, security and identity. By contrast, groups make people feel secure and anchored, but also help to fragment civil society into separate cliques, unknown to one another. This is the outcome of more than 20 years of ideological battles over what sort of social space the internet should be.

For a few years at the dawn of the millennium, the O’Reilly Emerging Technology Conferences (or ETech), were a crucible in which a new digital world was imagined and debated. Launched by the west coast media entrepreneur Tim O’Reilly and hosted annually around California, the conferences attracted a mixture of geeks, gurus, designers and entrepreneurs, brought together more in a spirit of curiosity than of commerce. In 2005, O’Reilly coined the term “web 2.0” to describe a new wave of websites that connected users with each other, rather than with existing offline institutions. Later that year, the domain name facebook.com was purchased by a 21-year-old Harvard student, and the age of the giant social media platforms was born.

Within this short window of time, we can see competing ideas of what a desirable online community might look like. The more idealistic tech gurus who attended ETech insisted that the internet should remain an open public space, albeit one in which select communities could cluster for their own particular purposes, such as creating open-source software projects or Wikipedia entries. The untapped potential of the internet, they believed, was for greater democracy. But for companies such as Facebook, the internet presented an opportunity to collect data about users en masse. The internet’s potential was for greater surveillance. The rise of the giant platforms from 2005 onwards suggested the latter view had won out. And yet, in a strange twist, we are now witnessing a revival of anarchic, self-organising digital groups – only now, in the hands of Facebook as well. The two competing visions have collided.

Mark Zuckerberg talking about privacy at a Facebook conference in 2019. Photograph: Amy Osborne/AFP/Getty Images

To see how this story unfolded, it’s worth going back to 2003. At the ETech conference that year, a keynote speech was given by the web enthusiast and writer Clay Shirky, now an academic at New York University, which surprised its audience by declaring that the task of designing successful online communities had little to do with technology at all. The talk looked back at one of the most fertile periods in the history of social psychology, and was entitled “A group is its own worst enemy”.

Shirky drew on the work of the British psychoanalyst and psychologist Wilfred Bion, who, together with Kurt Lewin, was one of the pioneers of the study of “group dynamics” in the 40s. The central proposition of this school was that groups possess psychological properties that exist independently of their individual members. In groups, people find themselves behaving in ways that they never would if left to their own devices.

Like Stanley Milgram’s notorious series of experiments to test obedience in the early 60s – in which some participants were persuaded to administer apparently painful electric shocks to others – the mid-20th century concern with group dynamics grew in the shadow of the political horrors of the 30s and 40s, which had posed grave questions about how individuals come to abandon their ordinary sense of morality. Lewin and Bion posited that groups possess distinctive personalities, which emerge organically through the interaction of their members, independently of what rules they might have been given, or what individuals might rationally do alone.

With the dawn of the 60s, and its more individualistic political hopes, psychologists’ interest in groups started to wane. The assumption that individuals are governed by conformity fell by the wayside. When Shirky introduced Bion’s work at the O’Reilly conference in 2003, he was going out on a limb. What he correctly saw was that, in the absence of any explicit structures or rules, online communities were battling against many of the disruptive dynamics that fascinated the psychologists of the 40s.

Shirky highlighted one area of Bion’s work in particular: how groups can spontaneously sabotage their own stipulated purpose. The beauty of early online communities, such as listservs, message boards and wikis, was their spirit of egalitarianism, humour and informality. But these same properties often worked against them when it came to actually getting anything constructive done, and could sometimes snowball into something obstructive or angry. Once the mood of a group was diverted towards jokes, disruption or hostility towards another group, it became very difficult to wrest it back.

Bion’s concerns originated in fear of humanity’s darker impulses, but the vision Shirky was putting to his audience that day was a more optimistic one. If the designers of online spaces could preempt disruptive “group dynamics”, he argued, then it might be possible to support cohesive, productive online communities that remained open and useful at the same time. Like a well designed park or street, a well-designed online space might nurture healthy sociability without the need for policing, surveillance or closure to outsiders. Between one extreme of anarchic chaos (constant trolling), and another of strict moderation and regulation of discussion (acceding to an authority figure), thinking in terms of group dynamics held out the promise of a social web that was still largely self-organising, but also relatively orderly.

But there was another solution to this same problem waiting in the wings, which would turn out to be world-changing in its consequences: forget group dynamics, and focus on reputation dynamics instead. If someone online has a certain set of offline attributes, such as a job title, an album of tagged photos, a list of friends and an email address, they will behave themselves in ways that are appropriate to all of these fixed public identifiers. Add more and more surveillance into the mix, both by one’s peers and by corporations, and the problem of spontaneous group dynamics disappears. It is easier to hold on to your self-control and your conscience if you are publicly visible, including to friends, extended family and colleagues.

For many of the Californian pioneers of cyberculture, who cherished online communities as an escape from the values and constraints of capitalist society, Zuckerberg’s triumph represents an unmitigated defeat. Corporations were never meant to seize control of this space. As late as 2005, the hope was that the social web would be built around democratic principles and bottom-up communities. Facebook abandoned all of that, by simply turning the internet into a multimedia telephone directory.

The last ETech was held in 2009. Within a decade, Facebook was being accused of pushing liberal democracy to the brink and even destroying truth itself. But as the demands of social media have become more onerous, with each of us curating a profile and projecting an identity, the lure of the autonomous group has resurfaced once again. In some respects, Shirky’s optimistic concern has now become today’s pessimistic one. Partly thanks to WhatsApp, the unmoderated, self-governing, amoral collective – larger than a conversation, smaller than a public – has become a dominant and disruptive political force in our society, much as figures such as Bion and Lewin feared.

Conspiracy theories and paranoid group dynamics were features of political life long before WhatsApp arrived. It makes no sense to blame the app for their existence, any more than it makes sense to blame Facebook for Brexit. But by considering the types of behaviour and social structures that technologies enable and enhance, we get a better sense of some of society’s characteristics and ailments. What are the general tendencies that WhatsApp helps to accelerate?

First of all, there is the problem of conspiracies in general. WhatsApp is certainly an unbeatable conduit for circulating conspiracy theories, but we must also admit that it seems to be an excellent tool for facilitating genuinely conspiratorial behaviour. One of the great difficulties when considering conspiracy theories in today’s world is that, regardless of WhatsApp, some conspiracies turn out to be true: consider Libor-fixing, phone-hacking, or efforts by Labour party officials to thwart Jeremy Corbyn’s electoral prospects. These all happened, but one would have sounded like a conspiracy theorist to suggest them until they were later confirmed by evidence.

A communication medium that connects groups of up to 256 people, without any public visibility, operating via the phones in their pockets, is by its very nature, well-suited to supporting secrecy. Obviously not every group chat counts as a “conspiracy”. But it makes the question of how society coheres, who is associated with whom, into a matter of speculation – something that involves a trace of conspiracy theory. In that sense, WhatsApp is not just a channel for the circulation of conspiracy theories, but offers content for them as well. The medium is the message.

The full political potential of WhatsApp has not been witnessed in the UK. To date, it has not served as an effective political campaigning tool, partly because users seem reluctant to join large groups with people they don’t know. However, the influence – imagined or real – of WhatsApp groups within Westminster and the media undoubtedly contributes to the deepening sense that public life is a sham, behind which lurk invisible networks through which power is coordinated. WhatsApp has become a kind of “backstage” of public life, where it is assumed people articulate what they really think and believe in secret. This is a sensibility that has long fuelled conspiracy theories, especially antisemitic ones. Invisible WhatsApp groups now offer a modern update to the type of “explanation” that once revolved around Masonic lodges or the Rothschilds.

Away from the world of party politics and news media, there is the prospect of a society organised as a tapestry of overlapping cliques, each with their own internal norms. Groups are less likely to encourage heterodoxy or risk-taking, and more likely to inculcate conformity, albeit often to a set of norms hostile to those of the “mainstream”, whether that be the media, politics or professional public servants simply doing their jobs. In the safety of the group, it becomes possible to have one’s cake and eat it, to be simultaneously radical and orthodox, hyper-sceptical and yet unreflective.

For all the benefits that WhatsApp offers in helping people feel close to others, its rapid ascendency is one further sign of how a common public world – based upon verified facts and recognised procedures – is disintegrating. WhatsApp is well equipped to support communications on the margins of institutions and public discussion: backbenchers plotting coups, parents gossipping about teachers, friends sharing edgy memes, journalists circulating rumours, family members forwarding on unofficial medical advice. A society that only speaks honestly on the margins like this will find it harder to sustain the legitimacy of experts, officials and representatives who, by definition, operate in the spotlight. Meanwhile, distrust, alienation and conspiracy theories become the norm, chipping away at the institutions that might hold us together.

To see how this story unfolded, it’s worth going back to 2003. At the ETech conference that year, a keynote speech was given by the web enthusiast and writer Clay Shirky, now an academic at New York University, which surprised its audience by declaring that the task of designing successful online communities had little to do with technology at all. The talk looked back at one of the most fertile periods in the history of social psychology, and was entitled “A group is its own worst enemy”.

Shirky drew on the work of the British psychoanalyst and psychologist Wilfred Bion, who, together with Kurt Lewin, was one of the pioneers of the study of “group dynamics” in the 40s. The central proposition of this school was that groups possess psychological properties that exist independently of their individual members. In groups, people find themselves behaving in ways that they never would if left to their own devices.

Like Stanley Milgram’s notorious series of experiments to test obedience in the early 60s – in which some participants were persuaded to administer apparently painful electric shocks to others – the mid-20th century concern with group dynamics grew in the shadow of the political horrors of the 30s and 40s, which had posed grave questions about how individuals come to abandon their ordinary sense of morality. Lewin and Bion posited that groups possess distinctive personalities, which emerge organically through the interaction of their members, independently of what rules they might have been given, or what individuals might rationally do alone.

With the dawn of the 60s, and its more individualistic political hopes, psychologists’ interest in groups started to wane. The assumption that individuals are governed by conformity fell by the wayside. When Shirky introduced Bion’s work at the O’Reilly conference in 2003, he was going out on a limb. What he correctly saw was that, in the absence of any explicit structures or rules, online communities were battling against many of the disruptive dynamics that fascinated the psychologists of the 40s.

Shirky highlighted one area of Bion’s work in particular: how groups can spontaneously sabotage their own stipulated purpose. The beauty of early online communities, such as listservs, message boards and wikis, was their spirit of egalitarianism, humour and informality. But these same properties often worked against them when it came to actually getting anything constructive done, and could sometimes snowball into something obstructive or angry. Once the mood of a group was diverted towards jokes, disruption or hostility towards another group, it became very difficult to wrest it back.

Bion’s concerns originated in fear of humanity’s darker impulses, but the vision Shirky was putting to his audience that day was a more optimistic one. If the designers of online spaces could preempt disruptive “group dynamics”, he argued, then it might be possible to support cohesive, productive online communities that remained open and useful at the same time. Like a well designed park or street, a well-designed online space might nurture healthy sociability without the need for policing, surveillance or closure to outsiders. Between one extreme of anarchic chaos (constant trolling), and another of strict moderation and regulation of discussion (acceding to an authority figure), thinking in terms of group dynamics held out the promise of a social web that was still largely self-organising, but also relatively orderly.

But there was another solution to this same problem waiting in the wings, which would turn out to be world-changing in its consequences: forget group dynamics, and focus on reputation dynamics instead. If someone online has a certain set of offline attributes, such as a job title, an album of tagged photos, a list of friends and an email address, they will behave themselves in ways that are appropriate to all of these fixed public identifiers. Add more and more surveillance into the mix, both by one’s peers and by corporations, and the problem of spontaneous group dynamics disappears. It is easier to hold on to your self-control and your conscience if you are publicly visible, including to friends, extended family and colleagues.

For many of the Californian pioneers of cyberculture, who cherished online communities as an escape from the values and constraints of capitalist society, Zuckerberg’s triumph represents an unmitigated defeat. Corporations were never meant to seize control of this space. As late as 2005, the hope was that the social web would be built around democratic principles and bottom-up communities. Facebook abandoned all of that, by simply turning the internet into a multimedia telephone directory.

The last ETech was held in 2009. Within a decade, Facebook was being accused of pushing liberal democracy to the brink and even destroying truth itself. But as the demands of social media have become more onerous, with each of us curating a profile and projecting an identity, the lure of the autonomous group has resurfaced once again. In some respects, Shirky’s optimistic concern has now become today’s pessimistic one. Partly thanks to WhatsApp, the unmoderated, self-governing, amoral collective – larger than a conversation, smaller than a public – has become a dominant and disruptive political force in our society, much as figures such as Bion and Lewin feared.

Conspiracy theories and paranoid group dynamics were features of political life long before WhatsApp arrived. It makes no sense to blame the app for their existence, any more than it makes sense to blame Facebook for Brexit. But by considering the types of behaviour and social structures that technologies enable and enhance, we get a better sense of some of society’s characteristics and ailments. What are the general tendencies that WhatsApp helps to accelerate?

First of all, there is the problem of conspiracies in general. WhatsApp is certainly an unbeatable conduit for circulating conspiracy theories, but we must also admit that it seems to be an excellent tool for facilitating genuinely conspiratorial behaviour. One of the great difficulties when considering conspiracy theories in today’s world is that, regardless of WhatsApp, some conspiracies turn out to be true: consider Libor-fixing, phone-hacking, or efforts by Labour party officials to thwart Jeremy Corbyn’s electoral prospects. These all happened, but one would have sounded like a conspiracy theorist to suggest them until they were later confirmed by evidence.

A communication medium that connects groups of up to 256 people, without any public visibility, operating via the phones in their pockets, is by its very nature, well-suited to supporting secrecy. Obviously not every group chat counts as a “conspiracy”. But it makes the question of how society coheres, who is associated with whom, into a matter of speculation – something that involves a trace of conspiracy theory. In that sense, WhatsApp is not just a channel for the circulation of conspiracy theories, but offers content for them as well. The medium is the message.

The full political potential of WhatsApp has not been witnessed in the UK. To date, it has not served as an effective political campaigning tool, partly because users seem reluctant to join large groups with people they don’t know. However, the influence – imagined or real – of WhatsApp groups within Westminster and the media undoubtedly contributes to the deepening sense that public life is a sham, behind which lurk invisible networks through which power is coordinated. WhatsApp has become a kind of “backstage” of public life, where it is assumed people articulate what they really think and believe in secret. This is a sensibility that has long fuelled conspiracy theories, especially antisemitic ones. Invisible WhatsApp groups now offer a modern update to the type of “explanation” that once revolved around Masonic lodges or the Rothschilds.

Away from the world of party politics and news media, there is the prospect of a society organised as a tapestry of overlapping cliques, each with their own internal norms. Groups are less likely to encourage heterodoxy or risk-taking, and more likely to inculcate conformity, albeit often to a set of norms hostile to those of the “mainstream”, whether that be the media, politics or professional public servants simply doing their jobs. In the safety of the group, it becomes possible to have one’s cake and eat it, to be simultaneously radical and orthodox, hyper-sceptical and yet unreflective.

For all the benefits that WhatsApp offers in helping people feel close to others, its rapid ascendency is one further sign of how a common public world – based upon verified facts and recognised procedures – is disintegrating. WhatsApp is well equipped to support communications on the margins of institutions and public discussion: backbenchers plotting coups, parents gossipping about teachers, friends sharing edgy memes, journalists circulating rumours, family members forwarding on unofficial medical advice. A society that only speaks honestly on the margins like this will find it harder to sustain the legitimacy of experts, officials and representatives who, by definition, operate in the spotlight. Meanwhile, distrust, alienation and conspiracy theories become the norm, chipping away at the institutions that might hold us together.

Monday, 9 December 2019

Monday, 31 December 2018

We tell ourselves we choose our own life course, but is this ever true? The role of universities and advertising explored

By abetting the ad industry, universities are leading us into temptation, when they should be enlightening us writes George Monbiot in The Guardian

Surely, though, even if we are broadly shaped by the social environment, we control the small decisions we make? Sometimes. Perhaps. But here, too, we are subject to constant influence, some of which we see, much of which we don’t. And there is one major industry that seeks to decide on our behalf. Its techniques get more sophisticated every year, drawing on the latest findings in neuroscience and psychology. It is called advertising.

Every month, new books on the subject are published with titles like The Persuasion Code: How Neuromarketing Can Help You Persuade Anyone, Anywhere, Anytime. While many are doubtless overhyped, they describe a discipline that is rapidly closing in on our minds, making independent thought ever harder. More sophisticated advertising meshes with digital technologies designed to eliminate agency.

Earlier this year, the child psychologist Richard Freed explained how new psychological research has been used to develop social media, computer games and phones with genuinely addictive qualities. He quoted a technologist who boasts, with apparent justification: “We have the ability to twiddle some knobs in a machine learning dashboard we build, and around the world hundreds of thousands of people are going to quietly change their behaviour in ways that, unbeknownst to them, feel second-nature but are really by design.”

The purpose of this brain hacking is to create more effective platforms for advertising. But the effort is wasted if we retain our ability to resist it. Facebook, according to a leaked report, carried out research – shared with an advertiser – to determine when teenagers using its network feel insecure, worthless or stressed. These appear to be the optimum moments for hitting them with a micro-targeted promotion. Facebook denied that it offered “tools to target people based on their emotional state”.

We can expect commercial enterprises to attempt whatever lawful ruses they can pull off. It is up to society, represented by government, to stop them, through the kind of regulation that has so far been lacking. But what puzzles and disgusts me even more than this failure is the willingness of universities to host research that helps advertisers hack our minds. The Enlightenment ideal, which all universities claim to endorse, is that everyone should think for themselves. So why do they run departments in which researchers explore new means of blocking this capacity?

‘Facebook, according to a leaked report, developed tools to determine when teenagers using its network feel insecure, worthless or stressed.’ Photograph: Alamy Stock Photo

I ask because, while considering the frenzy of consumerism that rises beyond its usual planet-trashing levels at this time of year, I recently stumbled across a paper that astonished me. It was written by academics at public universities in the Netherlands and the US. Their purpose seemed to me starkly at odds with the public interest. They sought to identify “the different ways in which consumers resist advertising, and the tactics that can be used to counter or avoid such resistance”.

Among the “neutralising” techniques it highlighted were “disguising the persuasive intent of the message”; distracting our attention by using confusing phrases that make it harder to focus on the advertiser’s intentions; and “using cognitive depletion as a tactic for reducing consumers’ ability to contest messages”. This means hitting us with enough advertisements to exhaust our mental resources, breaking down our capacity to think.

Intrigued, I started looking for other academic papers on the same theme, and found an entire literature. There were articles on every imaginable aspect of resistance, and helpful tips on overcoming it. For example, I came across a paper that counsels advertisers on how to rebuild public trust when the celebrity they work with gets into trouble. Rather than dumping this lucrative asset, the researchers advised that the best means to enhance “the authentic persuasive appeal of a celebrity endorser” whose standing has slipped is to get them to display “a Duchenne smile”, otherwise known as “a genuine smile”. It precisely anatomised such smiles, showed how to spot them, and discussed the “construction” of sincerity and “genuineness”: a magnificent exercise in inauthentic authenticity.

Facebook told advertisers it can identify teens feeling 'insecure' and 'worthless'

Another paper considered how to persuade sceptical people to accept a company’s corporate social responsibility claims, especially when these claims conflict with the company’s overall objectives. (An obvious example is ExxonMobil’s attempts to convince people that it is environmentally responsible, because it is researching algal fuels that could one day reduce CO2 – even as it continues to pump millions of barrels of fossil oil a day). I hoped the paper would recommend that the best means of persuading people is for a company to change its practices. Instead, the authors’ research showed how images and statements could be cleverly combined to “minimise stakeholder scepticism”.

A further paper discussed advertisements that work by stimulating Fomo – fear of missing out. It noted that such ads work through “controlled motivation”, which is “anathema to wellbeing”. Fomo ads, the paper explained, tend to cause significant discomfort to those who notice them. It then went on to show how an improved understanding of people’s responses “provides the opportunity to enhance the effectiveness of Fomo as a purchase trigger”. One tactic it proposed is to keep stimulating the fear of missing out, during and after the decision to buy. This, it suggested, will make people more susceptible to further ads on the same lines.

Yes, I know: I work in an industry that receives most of its income from advertising, so I am complicit in this too. But so are we all. Advertising – with its destructive impacts on the living planet, our peace of mind and our free will – sits at the heart of our growth-based economy. This gives us all the more reason to challenge it. Among the places in which the challenge should begin are universities, and the academic societies that are supposed to set and uphold ethical standards. If they cannot swim against the currents of constructed desire and constructed thought, who can?

To what extent do we decide? We tell ourselves we choose our own life course, but is this ever true? If you or I had lived 500 years ago, our worldview, and the decisions we made as a result, would have been utterly different. Our minds are shaped by our social environment, in particular the belief systems projected by those in power: monarchs, aristocrats and theologians then; corporations, billionaires and the media today.

Humans, the supremely social mammals, are ethical and intellectual sponges. We unconsciously absorb, for good or ill, the influences that surround us. Indeed, the very notion that we might form our own minds is a received idea that would have been quite alien to most people five centuries ago. This is not to suggest we have no capacity for independent thought. But to exercise it, we must – consciously and with great effort – swim against the social current that sweeps us along, mostly without our knowledge.

Humans, the supremely social mammals, are ethical and intellectual sponges. We unconsciously absorb, for good or ill, the influences that surround us. Indeed, the very notion that we might form our own minds is a received idea that would have been quite alien to most people five centuries ago. This is not to suggest we have no capacity for independent thought. But to exercise it, we must – consciously and with great effort – swim against the social current that sweeps us along, mostly without our knowledge.

----Also Watch

The Day The Universe Changed

-----

Surely, though, even if we are broadly shaped by the social environment, we control the small decisions we make? Sometimes. Perhaps. But here, too, we are subject to constant influence, some of which we see, much of which we don’t. And there is one major industry that seeks to decide on our behalf. Its techniques get more sophisticated every year, drawing on the latest findings in neuroscience and psychology. It is called advertising.

Every month, new books on the subject are published with titles like The Persuasion Code: How Neuromarketing Can Help You Persuade Anyone, Anywhere, Anytime. While many are doubtless overhyped, they describe a discipline that is rapidly closing in on our minds, making independent thought ever harder. More sophisticated advertising meshes with digital technologies designed to eliminate agency.

Earlier this year, the child psychologist Richard Freed explained how new psychological research has been used to develop social media, computer games and phones with genuinely addictive qualities. He quoted a technologist who boasts, with apparent justification: “We have the ability to twiddle some knobs in a machine learning dashboard we build, and around the world hundreds of thousands of people are going to quietly change their behaviour in ways that, unbeknownst to them, feel second-nature but are really by design.”

The purpose of this brain hacking is to create more effective platforms for advertising. But the effort is wasted if we retain our ability to resist it. Facebook, according to a leaked report, carried out research – shared with an advertiser – to determine when teenagers using its network feel insecure, worthless or stressed. These appear to be the optimum moments for hitting them with a micro-targeted promotion. Facebook denied that it offered “tools to target people based on their emotional state”.

We can expect commercial enterprises to attempt whatever lawful ruses they can pull off. It is up to society, represented by government, to stop them, through the kind of regulation that has so far been lacking. But what puzzles and disgusts me even more than this failure is the willingness of universities to host research that helps advertisers hack our minds. The Enlightenment ideal, which all universities claim to endorse, is that everyone should think for themselves. So why do they run departments in which researchers explore new means of blocking this capacity?

‘Facebook, according to a leaked report, developed tools to determine when teenagers using its network feel insecure, worthless or stressed.’ Photograph: Alamy Stock Photo

I ask because, while considering the frenzy of consumerism that rises beyond its usual planet-trashing levels at this time of year, I recently stumbled across a paper that astonished me. It was written by academics at public universities in the Netherlands and the US. Their purpose seemed to me starkly at odds with the public interest. They sought to identify “the different ways in which consumers resist advertising, and the tactics that can be used to counter or avoid such resistance”.

Among the “neutralising” techniques it highlighted were “disguising the persuasive intent of the message”; distracting our attention by using confusing phrases that make it harder to focus on the advertiser’s intentions; and “using cognitive depletion as a tactic for reducing consumers’ ability to contest messages”. This means hitting us with enough advertisements to exhaust our mental resources, breaking down our capacity to think.

Intrigued, I started looking for other academic papers on the same theme, and found an entire literature. There were articles on every imaginable aspect of resistance, and helpful tips on overcoming it. For example, I came across a paper that counsels advertisers on how to rebuild public trust when the celebrity they work with gets into trouble. Rather than dumping this lucrative asset, the researchers advised that the best means to enhance “the authentic persuasive appeal of a celebrity endorser” whose standing has slipped is to get them to display “a Duchenne smile”, otherwise known as “a genuine smile”. It precisely anatomised such smiles, showed how to spot them, and discussed the “construction” of sincerity and “genuineness”: a magnificent exercise in inauthentic authenticity.

Facebook told advertisers it can identify teens feeling 'insecure' and 'worthless'

Another paper considered how to persuade sceptical people to accept a company’s corporate social responsibility claims, especially when these claims conflict with the company’s overall objectives. (An obvious example is ExxonMobil’s attempts to convince people that it is environmentally responsible, because it is researching algal fuels that could one day reduce CO2 – even as it continues to pump millions of barrels of fossil oil a day). I hoped the paper would recommend that the best means of persuading people is for a company to change its practices. Instead, the authors’ research showed how images and statements could be cleverly combined to “minimise stakeholder scepticism”.

A further paper discussed advertisements that work by stimulating Fomo – fear of missing out. It noted that such ads work through “controlled motivation”, which is “anathema to wellbeing”. Fomo ads, the paper explained, tend to cause significant discomfort to those who notice them. It then went on to show how an improved understanding of people’s responses “provides the opportunity to enhance the effectiveness of Fomo as a purchase trigger”. One tactic it proposed is to keep stimulating the fear of missing out, during and after the decision to buy. This, it suggested, will make people more susceptible to further ads on the same lines.

Yes, I know: I work in an industry that receives most of its income from advertising, so I am complicit in this too. But so are we all. Advertising – with its destructive impacts on the living planet, our peace of mind and our free will – sits at the heart of our growth-based economy. This gives us all the more reason to challenge it. Among the places in which the challenge should begin are universities, and the academic societies that are supposed to set and uphold ethical standards. If they cannot swim against the currents of constructed desire and constructed thought, who can?

Thursday, 12 October 2017

Data is not the new oil

How do you know when a pithy phrase or seductive idea has become fashionable in policy circles? When The Economist devotes a briefing to it.

Amol Rajan in BBC

In a briefing and accompanying editorial earlier this summer, that distinguished newspaper (it's a magazine, but still calls itself a newspaper, and I'm happy to indulge such eccentricity) argued that data is today what oil was a century ago.

As The Economist put it, "A new commodity spawns a lucrative, fast-growing industry, prompting anti-trust regulators to step in to restrain those who control its flow." Never mind that data isn't particularly new (though the volume may be) - this argument does, at first glance, have much to recommend it.

Just as a century ago those who got to the oil in the ground were able to amass vast wealth, establish near monopolies, and build the future economy on their own precious resource, so data companies like Facebook and Google are able to do similar now. With oil in the 20th century, a consensus eventually grew that it would be up to regulators to intervene and break up the oligopolies - or oiliogopolies - that threatened an excessive concentration of power.

Many impressive thinkers have detected similarities between data today and oil in yesteryear. John Thornhill, the Financial Times's Innovation Editor, has used the example of Alaska to argue that data companies should pay a universal basic income, another idea that has become highly fashionable in policy circles.

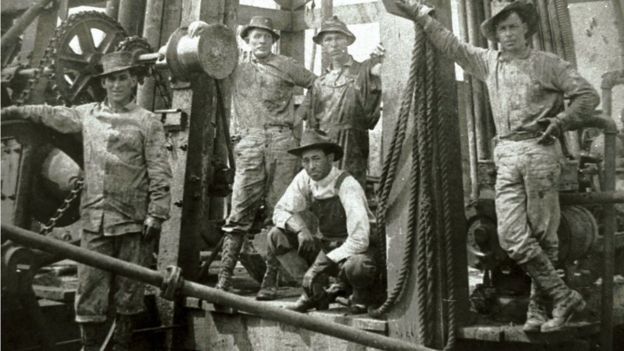

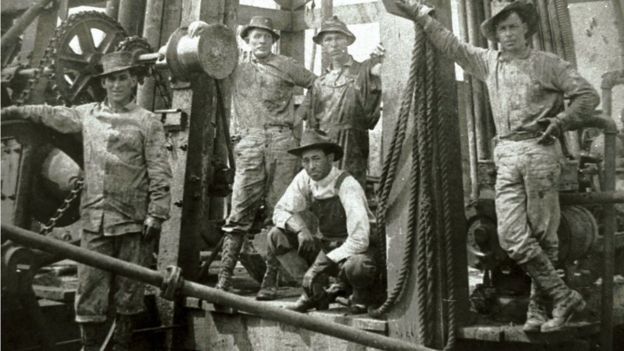

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESImage caption A drilling crew poses for a photograph at Spindletop Hill in Beaumont, Texas where the first Texas oil gusher was discovered in 1901.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESImage caption A drilling crew poses for a photograph at Spindletop Hill in Beaumont, Texas where the first Texas oil gusher was discovered in 1901.

At first I was taken by the parallels between data and oil. But now I'm not so sure. As I argued in a series of tweets last week, there are such important differences between data today and oil a century ago that the comparison, while catchy, risks spreading a misunderstanding of how these new technology super-firms operate - and what to do about their power.

The first big difference is one of supply. There is a finite amount of oil in the ground, albeit that is still plenty, and we probably haven't found all of it. But data is virtually infinite. Its supply is super-abundant. In terms of basic supply, data is more like sunlight than oil: there is so much of it that our principal concern should be more what to do with it than where to find more, or how to share that which we've already found.

Data can also be re-used, and the same data can be used by different people for different reasons. Say I invented a new email address. I might use that to register for a music service, where I left a footprint of my taste in music; a social media platform on which I upload photos of my baby son; and a search engine, where I indulge my fascination with reggae.

If, through that email address, a data company were able to access information about me or my friends, the music service, the social network and the search engine might all benefit from that one email address and all that is connected to it. This is different from oil. If a major oil company get to an oil field in, say, Texas, they alone will have control of the oil there - and once they've used it up, it's gone.

Legitimate fears

This points to another key difference: who controls the commodity. There are very legitimate fears about the use and abuse of personal data online - for instance, by foreign powers trying to influence elections. And very few people have a really clear idea about the digital footprint they have left online. If they did know, they might become obsessed with security. I know a few data fanatics who own several phones and indulge data-savvy habits, such as avoiding all text messages in favour of WhatsApp, which is encrypted.

But data is something which - in theory if not in practice - the user can control, and which ideally - though again the practice falls well short - spreads by consent. Going back to that oil company, it's largely up to them how they deploy the oil in the ground beneath Texas: how many barrels they take out every day, what price they sell it for, who they sell it to.

With my email address, it's up to me whether to give it to that music service, social network, or search engine. If I don't want people to know that I have an unhealthy obsession with bands such as The Wailers, The Pioneers and The Ethiopians, I can keep digitally schtum.

Now, I realise that in practice, very few people feel they have control over their personal data online; and retrieving your data isn't exactly easy. If I tried to reclaim, or wipe from the face of the earth, all the personal data that I've handed over to data companies, it'd be a full time job for the rest of my life and I'd never actually achieve it. That said, it is largely as a result of my choices that these firms have so much of my personal data.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESImage captionServers for data storage in Hafnarfjordur, Iceland, which is trying to make a name for itself in the business of data centres - warehouses that consume enormous amounts of energy to store the information of 3.2 billion internet users.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESImage captionServers for data storage in Hafnarfjordur, Iceland, which is trying to make a name for itself in the business of data centres - warehouses that consume enormous amounts of energy to store the information of 3.2 billion internet users.

Amol Rajan in BBC

In a briefing and accompanying editorial earlier this summer, that distinguished newspaper (it's a magazine, but still calls itself a newspaper, and I'm happy to indulge such eccentricity) argued that data is today what oil was a century ago.

As The Economist put it, "A new commodity spawns a lucrative, fast-growing industry, prompting anti-trust regulators to step in to restrain those who control its flow." Never mind that data isn't particularly new (though the volume may be) - this argument does, at first glance, have much to recommend it.

Just as a century ago those who got to the oil in the ground were able to amass vast wealth, establish near monopolies, and build the future economy on their own precious resource, so data companies like Facebook and Google are able to do similar now. With oil in the 20th century, a consensus eventually grew that it would be up to regulators to intervene and break up the oligopolies - or oiliogopolies - that threatened an excessive concentration of power.

Many impressive thinkers have detected similarities between data today and oil in yesteryear. John Thornhill, the Financial Times's Innovation Editor, has used the example of Alaska to argue that data companies should pay a universal basic income, another idea that has become highly fashionable in policy circles.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESImage caption A drilling crew poses for a photograph at Spindletop Hill in Beaumont, Texas where the first Texas oil gusher was discovered in 1901.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESImage caption A drilling crew poses for a photograph at Spindletop Hill in Beaumont, Texas where the first Texas oil gusher was discovered in 1901.At first I was taken by the parallels between data and oil. But now I'm not so sure. As I argued in a series of tweets last week, there are such important differences between data today and oil a century ago that the comparison, while catchy, risks spreading a misunderstanding of how these new technology super-firms operate - and what to do about their power.

The first big difference is one of supply. There is a finite amount of oil in the ground, albeit that is still plenty, and we probably haven't found all of it. But data is virtually infinite. Its supply is super-abundant. In terms of basic supply, data is more like sunlight than oil: there is so much of it that our principal concern should be more what to do with it than where to find more, or how to share that which we've already found.

Data can also be re-used, and the same data can be used by different people for different reasons. Say I invented a new email address. I might use that to register for a music service, where I left a footprint of my taste in music; a social media platform on which I upload photos of my baby son; and a search engine, where I indulge my fascination with reggae.