'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Thursday, 4 April 2024

Wednesday, 3 April 2024

Saturday, 22 April 2023

A Confidence Artist (con man) Satisfies a Basic Human Need

“Religion began when the first scoundrel met the first fool.’ Voltaire

The above quote is accurate because it touches on a profound truth. The truth of our absolute and total need for belief from our early moments of consciousness till we die.

In some ways, confidence artists have it easy. We’ve done most of the work for them; we want to believe in what they’re telling us. Their genius lies in figuring out what, precisely, it is we want and how they can present themselves as the perfect vehicle for delivering on that desire.

Confidence men are sometimes referred to as the ‘aristocrats of crime’. Hard crime - theft, burglary, violence is not what the confidence artist is about. The confidence game - the con - is about soft skills. Trust, sympathy, persuasion. The true con artist doesn’t force us to do anything; he makes us complicit in our own undoing. He doesn’t steal. We give. He doesn’t have to threaten us. We supply the story ourselves. We believe because we want to, not because anyone made us. And so we offer up whatever they want - money, reputation, trust, fame, legitimacy, support - and we don’t realise what is happening until it is too late.

Our need to believe, to embrace things that explain our world, is as pervasive as it is strong. Given the right cues, we’re willing to go along with just about anything and put our confidence in just about anyone. Conspiracy theories, supernatural phenomena, psychics; we have a seemingly bottomless capacity for credulity.

Or, as one psychologist put it, ‘Gullibility may be deeply engrained in the human behavioural repertoire.’ For our minds are built for stories. We crave them, and, when there aren’t ready ones available, we create them. Stories about our origins. Our purpose. The reasons the world is the way it is.

Human beings don’t like to exist in a state of uncertainty or ambiguity. When something doesn’t make sense we want to supply the missing link. When we don’t understand what or why or how something happened, we want to find the explanation. A confidence artist is only too happy to comply - and the well-crafted narrative is his absolute forte.

Extracted from The Confidence Game by Maria Konnikova

Monday, 31 December 2018

We tell ourselves we choose our own life course, but is this ever true? The role of universities and advertising explored

Humans, the supremely social mammals, are ethical and intellectual sponges. We unconsciously absorb, for good or ill, the influences that surround us. Indeed, the very notion that we might form our own minds is a received idea that would have been quite alien to most people five centuries ago. This is not to suggest we have no capacity for independent thought. But to exercise it, we must – consciously and with great effort – swim against the social current that sweeps us along, mostly without our knowledge.

Surely, though, even if we are broadly shaped by the social environment, we control the small decisions we make? Sometimes. Perhaps. But here, too, we are subject to constant influence, some of which we see, much of which we don’t. And there is one major industry that seeks to decide on our behalf. Its techniques get more sophisticated every year, drawing on the latest findings in neuroscience and psychology. It is called advertising.

Every month, new books on the subject are published with titles like The Persuasion Code: How Neuromarketing Can Help You Persuade Anyone, Anywhere, Anytime. While many are doubtless overhyped, they describe a discipline that is rapidly closing in on our minds, making independent thought ever harder. More sophisticated advertising meshes with digital technologies designed to eliminate agency.

Earlier this year, the child psychologist Richard Freed explained how new psychological research has been used to develop social media, computer games and phones with genuinely addictive qualities. He quoted a technologist who boasts, with apparent justification: “We have the ability to twiddle some knobs in a machine learning dashboard we build, and around the world hundreds of thousands of people are going to quietly change their behaviour in ways that, unbeknownst to them, feel second-nature but are really by design.”

The purpose of this brain hacking is to create more effective platforms for advertising. But the effort is wasted if we retain our ability to resist it. Facebook, according to a leaked report, carried out research – shared with an advertiser – to determine when teenagers using its network feel insecure, worthless or stressed. These appear to be the optimum moments for hitting them with a micro-targeted promotion. Facebook denied that it offered “tools to target people based on their emotional state”.

We can expect commercial enterprises to attempt whatever lawful ruses they can pull off. It is up to society, represented by government, to stop them, through the kind of regulation that has so far been lacking. But what puzzles and disgusts me even more than this failure is the willingness of universities to host research that helps advertisers hack our minds. The Enlightenment ideal, which all universities claim to endorse, is that everyone should think for themselves. So why do they run departments in which researchers explore new means of blocking this capacity?

‘Facebook, according to a leaked report, developed tools to determine when teenagers using its network feel insecure, worthless or stressed.’ Photograph: Alamy Stock Photo

I ask because, while considering the frenzy of consumerism that rises beyond its usual planet-trashing levels at this time of year, I recently stumbled across a paper that astonished me. It was written by academics at public universities in the Netherlands and the US. Their purpose seemed to me starkly at odds with the public interest. They sought to identify “the different ways in which consumers resist advertising, and the tactics that can be used to counter or avoid such resistance”.

Among the “neutralising” techniques it highlighted were “disguising the persuasive intent of the message”; distracting our attention by using confusing phrases that make it harder to focus on the advertiser’s intentions; and “using cognitive depletion as a tactic for reducing consumers’ ability to contest messages”. This means hitting us with enough advertisements to exhaust our mental resources, breaking down our capacity to think.

Intrigued, I started looking for other academic papers on the same theme, and found an entire literature. There were articles on every imaginable aspect of resistance, and helpful tips on overcoming it. For example, I came across a paper that counsels advertisers on how to rebuild public trust when the celebrity they work with gets into trouble. Rather than dumping this lucrative asset, the researchers advised that the best means to enhance “the authentic persuasive appeal of a celebrity endorser” whose standing has slipped is to get them to display “a Duchenne smile”, otherwise known as “a genuine smile”. It precisely anatomised such smiles, showed how to spot them, and discussed the “construction” of sincerity and “genuineness”: a magnificent exercise in inauthentic authenticity.

Facebook told advertisers it can identify teens feeling 'insecure' and 'worthless'

Another paper considered how to persuade sceptical people to accept a company’s corporate social responsibility claims, especially when these claims conflict with the company’s overall objectives. (An obvious example is ExxonMobil’s attempts to convince people that it is environmentally responsible, because it is researching algal fuels that could one day reduce CO2 – even as it continues to pump millions of barrels of fossil oil a day). I hoped the paper would recommend that the best means of persuading people is for a company to change its practices. Instead, the authors’ research showed how images and statements could be cleverly combined to “minimise stakeholder scepticism”.

A further paper discussed advertisements that work by stimulating Fomo – fear of missing out. It noted that such ads work through “controlled motivation”, which is “anathema to wellbeing”. Fomo ads, the paper explained, tend to cause significant discomfort to those who notice them. It then went on to show how an improved understanding of people’s responses “provides the opportunity to enhance the effectiveness of Fomo as a purchase trigger”. One tactic it proposed is to keep stimulating the fear of missing out, during and after the decision to buy. This, it suggested, will make people more susceptible to further ads on the same lines.

Yes, I know: I work in an industry that receives most of its income from advertising, so I am complicit in this too. But so are we all. Advertising – with its destructive impacts on the living planet, our peace of mind and our free will – sits at the heart of our growth-based economy. This gives us all the more reason to challenge it. Among the places in which the challenge should begin are universities, and the academic societies that are supposed to set and uphold ethical standards. If they cannot swim against the currents of constructed desire and constructed thought, who can?

Friday, 21 April 2017

Online political advertising is a black box and democracy should be worried

As your mind wearily contemplates being exposed to yet another political campaign, are your dreams haunted by battle buses, billboards and TV debates? Or is it Facebook, YouTube, Twitter and Google?

On the evidence of last year’s EU referendum, much of the campaigning, and much of the money spent on political advertising, will be online. And it will happen in a way that will be largely hidden from scrutiny by either the public or regulators.

During the referendum, Vote Leave spent £2.7m with one small Canadian digital marketing firm that specialises in political campaigns – Aggregate IQ. The sum was well over a third of Vote Leave’s total budget.

Two other campaign groups – both of which received large donations from the Leave campaign - gave Aggregate IQ a further £765,000, taking the total pumped through the company to almost £3.5m. Vote Leave director Dominic Cummings is quoted on the company’s website saying “We couldn’t have done it without them.”

Yet the invoices for the money they paid to Aggregate IQ, which were handed to the Electoral Commission, list vague jargon-filled specifications with little indication of how the ads were delivered. It may tell us Aggregate IQ were running a “targeted video app installed and display media campaign” but gives no clue about where those ads appeared or who saw them. Did most of the money go on Facebook or YouTube? Did they spend more money on reaching under 45s in Hull or pensioners in Canterbury? There’s no way of knowing, not least because the Electoral Commission doesn’t ask for the information.

Meanwhile Cambridge Analytica, the digital targeting experts part-owned by US billionaire Robert Mercer, were credited with super-charging the Leave.EU campaign, even getting a mention in a book about campaign by its chief funder Arron Banks. Yet according to filings with the Electoral Commission there was no paid relationship with the firm at all. The Electoral Commission is currently investigating, as is the Information Commissioner’s Office over the company’s use of data.

These two companies promise to sway the electorate using high-tech targeting of voters, yet not only does the Electoral Commission have little idea of how the money is being spent, but many of the different messages those campaigns show chosen sets of targets are hidden from the rest of us.

An ad in a newspaper or magazine, a billboard or tube poster, can be seen by anybody who happens to come across it. They are targeted in a blunt way, by location, readership etc, but who they are appealing to, the messages used and the money spent is clear for all to see.

But online, ads are directed at far more specific target groups, and shown only to them. Suspect someone is a bit racist? Show them pictures of dark skinned migrants lining up at a border. Know someone regularly visits Spain? Emphasise how much longer it will take to go through airport security.

Just as importantly, you can make sure that you don’t show the wrong ads to the wrong people. The racist dog whistle doesn’t get pushed at people likely to be from, or comfortable with, ethnic minorities. The lengthy customs checks don’t get shown to those with an all-consuming fear of terror attacks.

Of course, people will see ads that aren’t aimed at them online – the targeting is far from perfect - but the digital world allows paid-for political campaigning to split into numerous conversations that rarely overlap.

This combination of digital marketing firms that are required to reveal little about what they do, and digital ads that are different for each segment of the population, make political advertising online opaque in way traditional ads were not.

And the approach seems to work. A more sophisticated digital strategy is regularly cited by Cummings and other Leave campaigners as as example of how they outsmarted Remain. If you were planning how to win June’s election, you’d be mad not to pay close attention to how they did it, and do your best to replicate it. And that means as we approach yet another nationwide vote, it will be harder than ever to see what impact money and the political advertising it pays for is having on the result.

Friday, 24 June 2016

David Ogilvy’s 20 unconventional rules for getting clients

Why? The fear of losing them, alone, will wreck your life. You will be unable to give candid advice, and “slowly become a lackey”. David Ogilvy once turned down Ford, saying: “Your account would represent one-half of our total billing. This would make it difficult for us to sustain our independence in council.” Landing your ideal client immediately may not be as great for your business as you think.

This can be tough when you need work, but if a client approaches you who you know won’t be able to stay in business, regardless of if they hire you, don’t take them on. It doesn’t matter how great your work is, nothing you do will make up for their deficiencies. You may be hungry for work, but the success of your clients, ultimately defines you. Your profit margin is too slim to survive a prospective client’s bankruptcy.

If a client announced they were considering hiring Ogilvy, he would withdraw his company from the race. His reason? “I like to succeed in public, fail in secret.”

David picked this up from antique dealers. He realized that when a dealer drew your attention to a flaw in the furniture, he almost always gained your trust. If you do this too — before the client notices your flaws on their own, you will also gain their trust. It will make you more credible when you boast about your strong points.

These things put prospects to sleep. “No manufacturer ever hired an agency because it increased market-share for somebody else.” Clients care about themselves, talk about them.

Always do it for the same reason: if their behavior erodes the morale of the people working on their account. Do not allow this from any client.

Tuesday, 19 April 2016

These are the psychological tricks both sides of the EU debate are playing on you - and how to recognise them

Ben Chu in The Independent

Imagine you’re lucky. Imagine you receive £50 from a benefactor. But, oh dear, there’s a problem with the gift. It turns out too much was paid out. There has to be a financial correction. So you’re faced with a choice.

So would you rather keep £20? Or lose £30? Think very quickly. Did you initially lean towards keeping £20? Many people do. But of course they amount to the same thing. You’d still have £20 whichever option you picked.

So what’s going on? Why did £20 look more appealing? That’s the brain’s “system one” at work, according to psychologists. Studies show that the reactive human mind sees the “keep” flashing in red lights before there’s any mental arithmetic (even before trivial calculations such as subtracting £30 from £50). And the word “loss” is also deeply off-putting to the mind’s system one. A quick decision framed as a straight choice between “keep” and “lose” will usually see “lose” rejected.

The mental arithmetic is “system two” and it takes much longer to be activated in most of us than system one. Sadly, many of us don’t even bother activating system two before making decisions at all.

Advertisers are aware of this bias. That’s why they often frame propositions in terms of how much money people can keep rather than how much they’ve lost in the past. “Keep more of your savings income by opening an ISA”, “Keep more of your money when you shop with us”, and so on.

Political advertisers are on to it too. That’s why the Leave campaign ahead of June’s European Union referendum have been emphasising so heavily the prize of keeping the UK’s £13bn annual contribution to the EU Budget. They emphasise what we can keep by voting to leave. Yet the Remain campaign is familiar with this tactic too. That’s why they emphasise the 3m UK jobs “linked to trade with the rest of Europe”. We naturally want to keep all those jobs, don’t we?

Both claims are actually tendentious. The £13bn is the gross contribution of the UK to Brussels – it doesn’t account for the money the UK receives back. And it’s silly to imply that 3m jobs would disappear overnight in the event of a Brexit. That would only happen if all trade between Britain and the Continent came to a sudden halt – something no one seriously expects. But the campaigners are not really trying to impart useful information with their soundbites – they’re aiming at the system one part of your brain.

That’s by no means the only psychological bias battleground in this referendum campaign. Psychologists talk of the power of “framing”. Which sounds more appealing: 90 per cent fat-free or 10 per cent fat? Advertisers know the answer, which is why one never sees the latter formulation even though they describe the same product.

Now consider which sounds like a more compelling argument in the context of an EU membership vote. “Almost half of everything we sell to the rest of the world we sell to Europe,” says the Stronger in Europe campaign. “British reliance on trade with the EU has fallen to an all-time low,” proclaim the Outers. The fact that both sound compelling - and both describe the same statistics - shows that the two campaigns grasp the importance of framing.

There’s more. What sounds worse: a shortfall of 6 per cent of GDP resulting from Brexit, or a loss of £4,300 per household? For many people it will be the latter figure, heavily highlighted by George Osborne yesterday. But, again, they amount to the same thing. £4,300 is merely the 6 per cent of GDP translated into cash terms and divided by all the 26m households in the country.

So why does £4,300 sound more off-putting to most people? Here we have the “ratio bias” at work. In any ratio there is the numerator and the denominator. In the two statistics above “6” and “£4,400” are the numerators. And “GDP” and “per household” are the denominators. Studies show that the system one part of our brain is more sensitive to big numbers in the numerator of ratios, and often neglects the denominators. So £4,300 sets off larger movements in many brains because, quite simply, it’s a bigger sounding figure than 6.

Consider another example. Which is the more compelling fact: “200,000 UK businesses trade with the EU” or: “Only 6 per cent of UK firms export to the EU”? The first is from the Stronger in Europe website. The second is from Vote Leave. Here the Outers are trying to use the ratio bias to minimise the sense of importance of the EU as a trading partner for British firms - and the Inners are doing precisely the opposite.

We are profoundly influenced by the framing of statistics. Quite understandably, politicians and campaigners seek to manipulate your system one brain. “I just feel I don’t know who to trust and I need a voice I can trust,” said a member of a panel of “undecided” referendum voters on the BBC’s Newsnight last night. But that benign and trustworthy figure does not exist. The way the facts are laid out will depend on the way the person wants the facts to be framed. Asking for someone to do the job for you - and placing your trust in them - essentially means asking that person to steer you in one way or the other.

If people genuinely want to make up their minds without bias, they are on their own. And their only trustworthy guide is their own brain’s system two.

Sunday, 22 November 2015

What if I fail?

We are all failures. Every one of us.

That’s not always how it looks, of course. Other people seem so successful. Their own PR machines paint a positive picture. They are perpetually “excited” on Twitter about their new project. Their photos on Facebook show them looking happy and smiley.

Seen from the outside, our friends always seem to be earning more money than us. They have bigger houses and go on sunnier holidays. And we are surrounded by images of wealth. All I see when I walk the streets of London are fleets of black jeep-like cars everywhere, which has the effect of making me feel like a failure because I am skint.

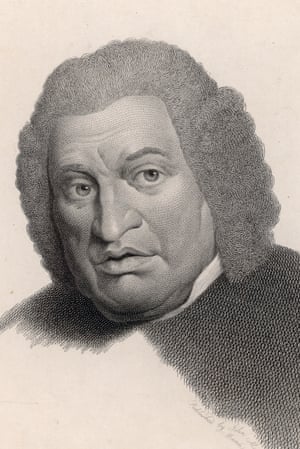

Aristotle felt we needed to make space for quiet study. Photograph: Hulton Getty

Add to that the sense that my contemporaries all seem to be writing best-selling novels or acting in Hollywood films or making tons of money somehow or other, and the sense of failure can easily creep up on you.

But if only we knew what failures other people felt, then we would not feel like failures. As Dr Johnson wrote in the mid-18th century: “All envy would be extinguished, if it were universally known that there are none to be envied, and surely none can much be envied who are not pleased with themselves.” Yes, and that even includes Johnny Depp. Can you imagine being an actor? Blimey, the insecurity of it.

Johnson’s advice was simple: drink, forget and take a nap. Sip the nectar of oblivion and conjure up happy fantasies while in a state of semi-slumber.

And what about the home lives of the rich and successful? Any amount of fame and money cannot compensate for bad relationships. Every life is full of joy and woe, probably in equal measure, so envy makes no sense whatsoever. In fact, to be envious at all shows a stunning lack of empathy, an inability to put yourself in another person’s shoes. Everyone suffers.

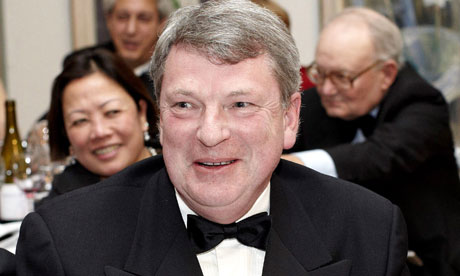

Sir Paul McCartney said no matter how far you get, you feel everyone is doing better than you. Photograph: Steve Parsons/PA

Even the most successful man in the world doesn’t feel successful. Who has done better than Paul McCartney? But he said in a 2013 interview: “No matter how accomplished you get – and I know a lot of people who are very accomplished – you feel that everyone is doing better than you, that it’s easier for them. You’ve got to the top of your profession – you’re now prime minister – but you still get shit off everyone.”

Successful people are failures because they have dozens of failed projects behind them. We tend only to see the successes. I’ve been reading a lot of business books recently, and if there is one thing that all entrepreneurs have in common, it’s a stunning track record of colossal disasters. Failure and success, then, are the same thing. Two sides of the same coin.

It is said that all political careers end in failure. And the merchants, the city traders – they can lose fortunes as well as make them.

So how can we answer the question: what if I fail?

‘Dr Johnson’s advice was simple: drink, forget and take a nap.’ Photograph: Alamy

The only real answer is that we need to cultivate wisdom and to do that, we need to make space for quiet study. That, anyway, was the view of Aristotle. Like most of the ancient Greek philosophers, he believed that the answer to life was to “know thyself”; in other words, not to push yourself in the wrong direction, or to chase money or fame. He said that the life of a merchant was full of worry, and that the glories of a political life were brief and fleeting. The happy life, he wrote, was the contemplative life. If you can read books and enjoy doing nothing, you can always be happy.

Another great Greek philosopher was Zeno of Citium, the founder of the Stoic school. The Stoics were so called because they taught in the Stoa, the marketplace. They did not believe in getting away from it all like the Epicureans. They reckoned that you should put up with the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, and develop a detached attitude. Their trick was to imagine that you were flying into space and looking down on the world. From that distance, our little problems and issues seem like nothing more than vanity.

Failure is polite. To be imperfect is an act of courtesy to your fellow humans. In the same way, to appear to be hugely successful is an act of extreme rudeness, simply because it excites envy and jealousy in others. A friend of mine took to calling the glossy mag World of Interiors World of Inferiors because it made people feel bad. And this truth is admirably expressed in the title of Marge Simpson’s favourite magazine: Better Homes Than Yours.

Failures are lovable. Who is more popular: Homer Simpson or Donald Trump?

The writers of comedy can make us feel a whole lot better. They are almost the heirs to the Stoics. Comedy is all about disaster and failure and anxiety, and has a great healing power, by making us realise that we are not alone.

‘Failures are lovable. Who is more popular: Homer Simpson or Donald Trump?’ Photograph: Matt Groening/AP

We’d also do well to remember that the admen out there try to make us feel like failures because it’s good for business. The world of trade, exciting though it is, thrives on negative emotion. It identifies problems in your life and then offers to fix them. Lonely? Go on Facebook. Afraid of missing the moment? Photograph it and put it on Instagram. Sexless? Try Ashley Madison. Anxious? Drink beer. Onion breath? Chew gum. The business owners have a vested interest in making you feel like a failure. Poor? Join my get-rich-quick scheme.

This is not necessarily an evil process. In fact, it is completely natural. After all, if it is dark, you can light a candle. Human life is all about the light and shade. I just think it helps to understand that advertisers deliberately appeal to our sense of failure in order to sell stuff.

‘What did Samuel Beckett say? Fail again.’ Photograph: Jane Bown/Observer

What if I fail? It doesn’t matter. Who cares? Keep failing. It’s good for society, it’s good for you and it makes your friends feel better. What did Samuel Beckett say? “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Fail again. Fail better.”

Tuesday, 4 February 2014

Celebrities endorsing products also liable for misleading advertisements: Panel

Dipak Kumar Dash,TNN | Feb 4, 2014, 05.22 AM IST

The Central Consumer Protection Council(CCPC), under the chairmanship of minister K V Thomas, on Monday decided to set up a sub-committee to suggest strategies to deal with such advertisers. Among the concerns raised was peddling of products by celebrities.

"About 50% of the daylong conference was spent addressing ... the huge impact of misleading advertisements, particularly food items, hair oil and health products," said a CCPC member who attended the meeting in Kochi. "Even the celebrities must pay compensation in case there is a complaint," said Joseph Victor, a CCPC member.

Panel mulls measures to monitor ad claims

What seems to have moved the consumer affairs ministry is a direction from the MP high court to set up an ad monitoring panel as recommended by the Vibha Bhargava Commission. "An ad monitoring committee with proper budgetary support from the Centre may be set up to monitor the advertisements on regular basis... the committee will have the powers to (take) corrective actions and (impose) compensation," the CCPC said.

Sources said that the decision was taken unanimously by CCPC, which has members from central and state governments, besides representatives from consumer organizations and academicians. The sub-committee may be formed in less than a week and could submit its recommendations by February-end, sources said.

Some members told TOI the issue of southern superstar Mamootty endorsing products was discussed. "We have similar problems across the country. We have Shahrukh Khan or some other Hindi film star endorsing consumer items and they get huge payment for doing so. Misleading ads featuring such famous faces shown on TV even for a day serves the purpose of advertisers. We discussed how suo motu action can be taken against ads which have been withdrawn. Even the celebrities must pay compensation in case there is a complaint," said Joseph Victor, a CCPC member.

Another member, Ashim Sanyal, said he had raised the issue of monitoring ads, which are in huge numbers and across different modes and media. "We need to plan the mechanism for monitoring. The sub-committee will come out with directions and provisions to deal with the menace," he added. Lok Sabha MP Charles Dias, who also attended the meeting, told TOI that concerns were raised on manufacturers' ad spend, which is passed on to buyers. "Most of us felt that there should some sort of monitoring on how much is being spent on advertisements," he said.

Friday, 23 August 2013

Furniture stores used fake prices, says OFT

Tuesday, 16 July 2013

Cigarette packaging: the corporate smokescreen

Sunday, 7 July 2013

Failed by the lawyer

The judicial system is looking the other way as unscrupulous professional behaviour by advocates is causing distress to litigants and affecting their cases

Friday, 7 June 2013

Who hails the get-up-and-go spirit of the beggar on 50k a year?