'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label liberty. Show all posts

Showing posts with label liberty. Show all posts

Friday, 29 July 2022

Sunday, 8 August 2021

Sunday, 11 July 2021

Tuesday, 12 May 2020

Monday, 14 November 2016

Neoliberalism: the deep story that lies beneath Donald Trump’s triumph

George Monbiot in The Guardian

The events that led to Donald Trump’s election started in England in 1975. At a meeting a few months after Margaret Thatcher became leader of the Conservative party, one of her colleagues, or so the story goes, was explaining what he saw as the core beliefs of conservatism. She snapped open her handbag, pulled out a dog-eared book, and slammed it on the table. “This is what we believe,” she said. A political revolution that would sweep the world had begun.

The book was The Constitution of Liberty by Frederick Hayek. Its publication, in 1960, marked the transition from an honest, if extreme, philosophy to an outright racket. The philosophy was called neoliberalism. It saw competition as the defining characteristic of human relations. The market would discover a natural hierarchy of winners and losers, creating a more efficient system than could ever be devised through planning or by design. Anything that impeded this process, such as significant tax, regulation, trade union activity or state provision, was counter-productive. Unrestricted entrepreneurs would create the wealth that would trickle down to everyone.

This, at any rate, is how it was originally conceived. But by the time Hayek came to write The Constitution of Liberty, the network of lobbyists and thinkers he had founded was being lavishly funded by multimillionaires who saw the doctrine as a means of defending themselves against democracy. Not every aspect of the neoliberal programme advanced their interests. Hayek, it seems, set out to close the gap.

He begins the book by advancing the narrowest possible conception of liberty: an absence of coercion. He rejects such notions as political freedom, universal rights, human equality and the distribution of wealth, all of which, by restricting the behaviour of the wealthy and powerful, intrude on the absolute freedom from coercion he demands.

Democracy, by contrast, “is not an ultimate or absolute value”. In fact, liberty depends on preventing the majority from exercising choice over the direction that politics and society might take.

He justifies this position by creating a heroic narrative of extreme wealth. He conflates the economic elite, spending their money in new ways, with philosophical and scientific pioneers. Just as the political philosopher should be free to think the unthinkable, so the very rich should be free to do the undoable, without constraint by public interest or public opinion.

The ultra rich are “scouts”, “experimenting with new styles of living”, who blaze the trails that the rest of society will follow. The progress of society depends on the liberty of these “independents” to gain as much money as they want and spend it how they wish. All that is good and useful, therefore, arises from inequality. There should be no connection between merit and reward, no distinction made between earned and unearned income, and no limit to the rents they can charge.

Inherited wealth is more socially useful than earned wealth: “the idle rich”, who don’t have to work for their money, can devote themselves to influencing “fields of thought and opinion, of tastes and beliefs.” Even when they seem to be spending money on nothing but “aimless display”, they are in fact acting as society’s vanguard.

Hayek softened his opposition to monopolies and hardened his opposition to trade unions. He lambasted progressive taxation and attempts by the state to raise the general welfare of citizens. He insisted that there is “an overwhelming case against a free health service for all” and dismissed the conservation of natural resources.It should come as no surprise to those who follow such matters that he was awarded the Nobel prize for economics.

By the time Mrs Thatcher slammed his book on the table, a lively network of thinktanks, lobbyists and academics promoting Hayek’s doctrines had been established on both sides of the Atlantic, abundantly financed by some of the world’s richest people and businesses, including DuPont, General Electric, the Coors brewing company, Charles Koch, Richard Mellon Scaife, Lawrence Fertig, the William Volker Fund and the Earhart Foundation. Using psychology and linguistics to brilliant effect, the thinkers these people sponsored found the words and arguments required to turn Hayek’s anthem to the elite into a plausible political programme.

The ideologies Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan espoused were just two facets of neoliberalism. Photograph: Bettmann/Bettmann Archive

Thatcherism and Reaganism were not ideologies in their own right: they were just two faces of neoliberalism. Their massive tax cuts for the rich, crushing of trade unions, reduction in public housing, deregulation, privatisation, outsourcing and competition in public services were all proposed by Hayek and his disciples. But the real triumph of this network was not its capture of the right, but its colonisation of parties that once stood for everything Hayek detested.

Bill Clinton and Tony Blair did not possess a narrative of their own. Rather than develop a new political story, they thought it was sufficient to triangulate. In other words, they extracted a few elements of what their parties had once believed, mixed them with elements of what their opponents believed, and developed from this unlikely combination a “third way”.

It was inevitable that the blazing, insurrectionary confidence of neoliberalism would exert a stronger gravitational pull than the dying star of social democracy. Hayek’s triumph could be witnessed everywhere from Blair’s expansion of the private finance initiative to Clinton’s repeal of the Glass-Steagal Act, which had regulated the financial sector. For all his grace and touch, Barack Obama, who didn’t possess a narrative either (except “hope”), was slowly reeled in by those who owned the means of persuasion.

As I warned in April, the result is first disempowerment then disenfranchisement. If the dominant ideology stops governments from changing social outcomes, they can no longer respond to the needs of the electorate. Politics becomes irrelevant to people’s lives; debate is reduced to the jabber of a remote elite. The disenfranchised turn instead to a virulent anti-politics in which facts and arguments are replaced by slogans, symbols and sensation. The man who sank Hillary Clinton’s bid for the presidency was not Donald Trump. It was her husband.

The paradoxical result is that the backlash against neoliberalism’s crushing of political choice has elevated just the kind of man that Hayek worshipped. Trump, who has no coherent politics, is not a classic neoliberal. But he is the perfect representation of Hayek’s “independent”; the beneficiary of inherited wealth, unconstrained by common morality, whose gross predilections strike a new path that others may follow. The neoliberal thinktankers are now swarming round this hollow man, this empty vessel waiting to be filled by those who know what they want. The likely result is the demolition of our remaining decencies, beginning with the agreement to limit global warming.

Those who tell the stories run the world. Politics has failed through a lack of competing narratives. The key task now is to tell a new story of what it is to be a human in the 21st century. It must be as appealing to some who have voted for Trump and Ukip as it is to the supporters of Clinton, Bernie Sanders or Jeremy Corbyn.

A few of us have been working on this, and can discern what may be the beginning of a story. It’s too early to say much yet, but at its core is the recognition that – as modern psychology and neuroscience make abundantly clear – human beings, by comparison with any other animals, are both remarkably social and remarkably unselfish. The atomisation and self-interested behaviour neoliberalism promotes run counter to much of what comprises human nature.

Hayek told us who we are, and he was wrong. Our first step is to reclaim our humanity.

The events that led to Donald Trump’s election started in England in 1975. At a meeting a few months after Margaret Thatcher became leader of the Conservative party, one of her colleagues, or so the story goes, was explaining what he saw as the core beliefs of conservatism. She snapped open her handbag, pulled out a dog-eared book, and slammed it on the table. “This is what we believe,” she said. A political revolution that would sweep the world had begun.

The book was The Constitution of Liberty by Frederick Hayek. Its publication, in 1960, marked the transition from an honest, if extreme, philosophy to an outright racket. The philosophy was called neoliberalism. It saw competition as the defining characteristic of human relations. The market would discover a natural hierarchy of winners and losers, creating a more efficient system than could ever be devised through planning or by design. Anything that impeded this process, such as significant tax, regulation, trade union activity or state provision, was counter-productive. Unrestricted entrepreneurs would create the wealth that would trickle down to everyone.

This, at any rate, is how it was originally conceived. But by the time Hayek came to write The Constitution of Liberty, the network of lobbyists and thinkers he had founded was being lavishly funded by multimillionaires who saw the doctrine as a means of defending themselves against democracy. Not every aspect of the neoliberal programme advanced their interests. Hayek, it seems, set out to close the gap.

He begins the book by advancing the narrowest possible conception of liberty: an absence of coercion. He rejects such notions as political freedom, universal rights, human equality and the distribution of wealth, all of which, by restricting the behaviour of the wealthy and powerful, intrude on the absolute freedom from coercion he demands.

Democracy, by contrast, “is not an ultimate or absolute value”. In fact, liberty depends on preventing the majority from exercising choice over the direction that politics and society might take.

He justifies this position by creating a heroic narrative of extreme wealth. He conflates the economic elite, spending their money in new ways, with philosophical and scientific pioneers. Just as the political philosopher should be free to think the unthinkable, so the very rich should be free to do the undoable, without constraint by public interest or public opinion.

The ultra rich are “scouts”, “experimenting with new styles of living”, who blaze the trails that the rest of society will follow. The progress of society depends on the liberty of these “independents” to gain as much money as they want and spend it how they wish. All that is good and useful, therefore, arises from inequality. There should be no connection between merit and reward, no distinction made between earned and unearned income, and no limit to the rents they can charge.

Inherited wealth is more socially useful than earned wealth: “the idle rich”, who don’t have to work for their money, can devote themselves to influencing “fields of thought and opinion, of tastes and beliefs.” Even when they seem to be spending money on nothing but “aimless display”, they are in fact acting as society’s vanguard.

Hayek softened his opposition to monopolies and hardened his opposition to trade unions. He lambasted progressive taxation and attempts by the state to raise the general welfare of citizens. He insisted that there is “an overwhelming case against a free health service for all” and dismissed the conservation of natural resources.It should come as no surprise to those who follow such matters that he was awarded the Nobel prize for economics.

By the time Mrs Thatcher slammed his book on the table, a lively network of thinktanks, lobbyists and academics promoting Hayek’s doctrines had been established on both sides of the Atlantic, abundantly financed by some of the world’s richest people and businesses, including DuPont, General Electric, the Coors brewing company, Charles Koch, Richard Mellon Scaife, Lawrence Fertig, the William Volker Fund and the Earhart Foundation. Using psychology and linguistics to brilliant effect, the thinkers these people sponsored found the words and arguments required to turn Hayek’s anthem to the elite into a plausible political programme.

The ideologies Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan espoused were just two facets of neoliberalism. Photograph: Bettmann/Bettmann Archive

Thatcherism and Reaganism were not ideologies in their own right: they were just two faces of neoliberalism. Their massive tax cuts for the rich, crushing of trade unions, reduction in public housing, deregulation, privatisation, outsourcing and competition in public services were all proposed by Hayek and his disciples. But the real triumph of this network was not its capture of the right, but its colonisation of parties that once stood for everything Hayek detested.

Bill Clinton and Tony Blair did not possess a narrative of their own. Rather than develop a new political story, they thought it was sufficient to triangulate. In other words, they extracted a few elements of what their parties had once believed, mixed them with elements of what their opponents believed, and developed from this unlikely combination a “third way”.

It was inevitable that the blazing, insurrectionary confidence of neoliberalism would exert a stronger gravitational pull than the dying star of social democracy. Hayek’s triumph could be witnessed everywhere from Blair’s expansion of the private finance initiative to Clinton’s repeal of the Glass-Steagal Act, which had regulated the financial sector. For all his grace and touch, Barack Obama, who didn’t possess a narrative either (except “hope”), was slowly reeled in by those who owned the means of persuasion.

As I warned in April, the result is first disempowerment then disenfranchisement. If the dominant ideology stops governments from changing social outcomes, they can no longer respond to the needs of the electorate. Politics becomes irrelevant to people’s lives; debate is reduced to the jabber of a remote elite. The disenfranchised turn instead to a virulent anti-politics in which facts and arguments are replaced by slogans, symbols and sensation. The man who sank Hillary Clinton’s bid for the presidency was not Donald Trump. It was her husband.

The paradoxical result is that the backlash against neoliberalism’s crushing of political choice has elevated just the kind of man that Hayek worshipped. Trump, who has no coherent politics, is not a classic neoliberal. But he is the perfect representation of Hayek’s “independent”; the beneficiary of inherited wealth, unconstrained by common morality, whose gross predilections strike a new path that others may follow. The neoliberal thinktankers are now swarming round this hollow man, this empty vessel waiting to be filled by those who know what they want. The likely result is the demolition of our remaining decencies, beginning with the agreement to limit global warming.

Those who tell the stories run the world. Politics has failed through a lack of competing narratives. The key task now is to tell a new story of what it is to be a human in the 21st century. It must be as appealing to some who have voted for Trump and Ukip as it is to the supporters of Clinton, Bernie Sanders or Jeremy Corbyn.

A few of us have been working on this, and can discern what may be the beginning of a story. It’s too early to say much yet, but at its core is the recognition that – as modern psychology and neuroscience make abundantly clear – human beings, by comparison with any other animals, are both remarkably social and remarkably unselfish. The atomisation and self-interested behaviour neoliberalism promotes run counter to much of what comprises human nature.

Hayek told us who we are, and he was wrong. Our first step is to reclaim our humanity.

Tuesday, 9 February 2016

The curious case of Julian Assange

Editorial in The Hindu

Personal liberty still eludes WikiLeaks founder and Editor-in-Chief Julian Assange, despite a ruling by a United Nations legal panel that has declared his confinement “arbitrary and illegal”. The ruling of the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention — the authoritative UN body that pronounces on illegal detentions based on binding and legal international instruments — has met with support, but not surprisingly, with a bitter backlash as well, notably from governments that have suffered incalculable damage from WikiLeaks’ relentless exposures. Sweden and Britain have rejected the panel’s findings outright, despite the fact that they are signatories to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the European Convention on Human Rights and the other treaties upon which the UN legal panel has based its recommendation. The same countries have in the past upheld rulings of the same panel on similar cases such as the ‘arbitrary detention’ of the Myanmar leader Aung San Suu Kyi and former Maldives President Mohamed Nasheed. The British Foreign Secretary, Philip Hammond, has called the ruling “ridiculous”, and dismissed the distinguished panel as comprising “lay people, not lawyers”. As for the Swedish Prosecutor’s Office, it has declared that the UN body’s opinion “has no formal impact on the ongoing investigation, according to Swedish law”. In other words, both countries argue that his confinement is not arbitrary but self-imposed, and he is at ‘liberty’ to step out, be arrested, and face the consequences.

The specific allegation of rape that Mr. Assange faces in Sweden must be seen in the larger international political context of his confinement. He has made it clear he is not fleeing Swedish justice, offering repeatedly to give evidence to the Swedish authorities, with the caveat that he be questioned at his refuge in London, either in person or by webcam. While he will have to prove his innocence, Mr. Assange is not being paranoid when he talks of his fear of extradition to the U.S.: Chelsea Manning, whose damning Iraq revelations were first carried on WikiLeaks, was held in a long pre-trial detention and convicted to 35 years of imprisonment. The U.S. Department of Justice has confirmed on more than one occasion that there is a pending prosecution and Grand Jury against him and WikiLeaks. Mr. Assange’s defence team argues that the Swedish police case is but a smokescreen for a larger political game plan centred on Washington, which is determined to root out whistle-blowers such as Mr. Assange, Edward Snowden and Chelsea Manning for exposing dirty state secrets. It was WikiLeaks that carried the shocking video evidence of the wholesale collateral murder by the U.S.-led forces of civilians in Iraq and Afghanistan, in addition to thousands of pages of evidence of other violations of sovereignty and international law. By defying the UN panel’s carefully considered recommendation that Mr. Assange be freed and awarded compensation, Britain and Sweden are damaging their own international standing. They must reverse their untenable stand and do what law and decency dictate by allowing Mr. Assange an opportunity to prove his innocence without fearing extradition to the United States.

Personal liberty still eludes WikiLeaks founder and Editor-in-Chief Julian Assange, despite a ruling by a United Nations legal panel that has declared his confinement “arbitrary and illegal”. The ruling of the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention — the authoritative UN body that pronounces on illegal detentions based on binding and legal international instruments — has met with support, but not surprisingly, with a bitter backlash as well, notably from governments that have suffered incalculable damage from WikiLeaks’ relentless exposures. Sweden and Britain have rejected the panel’s findings outright, despite the fact that they are signatories to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the European Convention on Human Rights and the other treaties upon which the UN legal panel has based its recommendation. The same countries have in the past upheld rulings of the same panel on similar cases such as the ‘arbitrary detention’ of the Myanmar leader Aung San Suu Kyi and former Maldives President Mohamed Nasheed. The British Foreign Secretary, Philip Hammond, has called the ruling “ridiculous”, and dismissed the distinguished panel as comprising “lay people, not lawyers”. As for the Swedish Prosecutor’s Office, it has declared that the UN body’s opinion “has no formal impact on the ongoing investigation, according to Swedish law”. In other words, both countries argue that his confinement is not arbitrary but self-imposed, and he is at ‘liberty’ to step out, be arrested, and face the consequences.

The specific allegation of rape that Mr. Assange faces in Sweden must be seen in the larger international political context of his confinement. He has made it clear he is not fleeing Swedish justice, offering repeatedly to give evidence to the Swedish authorities, with the caveat that he be questioned at his refuge in London, either in person or by webcam. While he will have to prove his innocence, Mr. Assange is not being paranoid when he talks of his fear of extradition to the U.S.: Chelsea Manning, whose damning Iraq revelations were first carried on WikiLeaks, was held in a long pre-trial detention and convicted to 35 years of imprisonment. The U.S. Department of Justice has confirmed on more than one occasion that there is a pending prosecution and Grand Jury against him and WikiLeaks. Mr. Assange’s defence team argues that the Swedish police case is but a smokescreen for a larger political game plan centred on Washington, which is determined to root out whistle-blowers such as Mr. Assange, Edward Snowden and Chelsea Manning for exposing dirty state secrets. It was WikiLeaks that carried the shocking video evidence of the wholesale collateral murder by the U.S.-led forces of civilians in Iraq and Afghanistan, in addition to thousands of pages of evidence of other violations of sovereignty and international law. By defying the UN panel’s carefully considered recommendation that Mr. Assange be freed and awarded compensation, Britain and Sweden are damaging their own international standing. They must reverse their untenable stand and do what law and decency dictate by allowing Mr. Assange an opportunity to prove his innocence without fearing extradition to the United States.

Tuesday, 16 July 2013

Cigarette packaging: the corporate smokescreen

Noble sentiments about individual liberty are being used to bend democracy to the will of the tobacco industry

BETA

'Lynton Crosby personifies the new dispensation, in which men and women glide between corporations and politics, and appear to act as agents for big business within government.' Photograph: David Hartley / Rex Features

It's a victory for the hidden persuaders, the astroturfers, sock puppets, purchased scholars and corporate moles. On Friday the government announced that it will not oblige tobacco companies to sell cigarettes in plain packaging. How did it happen? The public was overwhelmingly in favour. The evidence that plain packets will discourage young people from smoking is powerful. But it fell victim to a lobbying campaign that was anything but plainly packaged.

Tobacco companies are not allowed to advertise their products. Nor, as they are so unpopular, can they appeal directly to the public. So they spend their cash on astroturfing(fake grassroots campaigns) and front groups. There is plenty of money to be made by people unscrupulous enough to take it.

Much of the anger about this decision has been focused on Lynton Crosby. Crosby is David Cameron's election co-ordinator. He also runs a lobbying company that works for the cigarette firms Philip Morris and British American Tobacco. He personifies the new dispensation, in which men and women glide between corporations and politics, and appear to act as agents for big business within government. The purpose of today's technocratic politics is to make democracy safe for corporations: to go through the motions of democratic consent while reshaping the nation at their behest.

But even if Crosby is sacked, the infrastructure of hidden persuasion will remain intact. Nor will it be affected by the register of lobbyists that David Cameron will announce on Tuesday, antiquated before it is launched.

Nanny state, health police, red tape, big government: these terms have been devised or popularised by corporate front groups. The companies who fund them are often ones that cause serious harm to human welfare. The front groups campaign not only against specific regulations, but also against the very principle of the democratic restraint of business.

I see the "free market thinktanks" as the most useful of these groups. Their purpose, I believe, is to invest corporate lobbying with authority. Mark Littlewood, the head of one of these thinktanks – the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) – has described plain packaging as "the latest ludicrous move in the unending, ceaseless, bullying war against those who choose to produce and consume tobacco". Over the past few days he's been in the media repeatedly, railing against the policy. So do the IEA's obsessions just happen to coincide with those of the cigarette firms? The IEA refuses to say who its sponsors are and how much they pay. But as a result of persistent digging, we now know that British American Tobacco, Philip Morris and Japan Tobacco International have been funding the institute – in BAT's case since 1963. British American Tobacco has admitted that it gave the institute £20,000 last year and that it's "planning to increase our contribution in 2013 and 2014".

Otherwise it's a void. The IEA tells me, "We do not accept any earmarked money for commissioned research work from any company." Really? But whether companies pay for specific publications or whether they continue to fund a body that – by the purest serendipity – publishes books and pamphlets that concur with the desires of its sponsors, surely makes no difference.

The institute has almost unrivalled access to the BBC and other media, where it promotes the corporate agenda without ever being asked to disclose its interests. Because they remain hidden, it retains a credibility its corporate funders lack. Amazingly, since 2011 Mark Littlewood has also been the government's adviser on cutting the regulations that business doesn't like. Corporate conflicts of interest intrude into the heart of this country's political life.

In 2002, a letter sent by the philosopher Roger Scruton to Japan Tobacco International (which manufactures Camel, Winston and Silk Cut) was leaked. In the letter, Professor Scruton complained that the £4,500 a month JTI was secretly paying him to place pro-tobacco articles in newspapers was insufficient: could they please raise it to £5,500?

Scruton was also working for the Institute of Economic Affairs, through which he published a major report attacking the World Health Organisation for trying to regulate tobacco. When his secret sponsorship was revealed, the IEA pronounced itself shocked: shocked to find that tobacco funding is going on in here. It claimed that "in the past we have relied on our authors to come forward with any competing interests, but that is going to change ... we are developing a policy to ensure it doesn't happen again." Oh yes? Eleven years later I have yet to find a declaration in any IEA publication that the institute (let alone the author) has been taking money from companies with an interest in its contents.

The IEA is one of several groups that appear to be used as a political battering ram by tobacco companies. On the TobaccoTactics website you can find similarly gruesome details about the financial interests and lobbying activities of, for example, the Adam Smith Institute and the Common Sense Alliance.

Even where tobacco funding is acknowledged, only half the story is told. Forest, a group that admits that "most of our money is donated by UK-based tobacco companies", has spawned a campaign against plain packaging called Hands Off Our Packs. The Department of Health has published some remarkable documents, alleging the blatant rigging of signatures on a petition launched by this campaign. Hands Off Our Packs is run by Angela Harbutt. She lives with Mark Littlewood.

Libertarianism in the hands of these people is a racket. All those noble sentiments about individual liberty, limited government and economic freedom are nothing but a smokescreen, a disguised form of corporate advertising. Whether Mark Littlewood, Lynton Crosby or David Cameron articulate it, it means the same thing: ideological cover for the corporations and the very rich.

Arguing against plain packaging on the Today programme, Mark Field MP, who came across as the transcendental form of an amoral, bumbling Tory twit, recited the usual tobacco company talking points, with their usual disingenuous disclaimers. In doing so, he made a magnificent slip of the tongue. "We don't want to encourage young people to take up advertising ... er, er, to take up tobacco smoking." He got it right the first time.

Friday, 15 February 2013

Secret funding helped build vast network of climate denial thinktanks

Anonymous billionaires donated $120m to more than 100 anti-climate groups working to discredit climate change science

• How Donors Trust distributed millions to anti-climate groups

• How Donors Trust distributed millions to anti-climate groups

- Suzanne Goldenberg, US environment correspondent

- guardian.co.uk,

Climate sceptic groups are mobilising against Obama’s efforts to act on climate change in his second term. Photograph: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

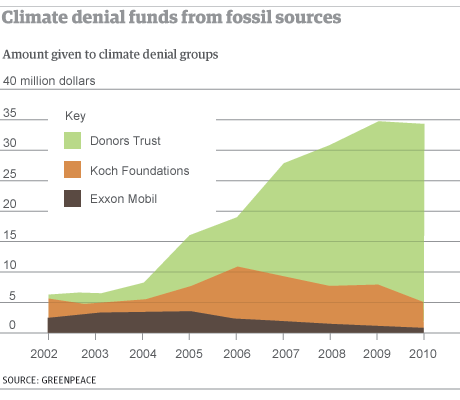

Conservative billionaires used a secretive funding route to channel nearly $120m (£77m) to more than 100 groups casting doubt about the science behind climate change, the Guardian has learned.

The funds, doled out between 2002 and 2010, helped build a vast network of thinktanks and activist groups working to a single purpose: to redefine climate change from neutral scientific fact to a highly polarising "wedge issue" for hardcore conservatives.

The millions were routed through two trusts, Donors Trust and the Donors Capital Fund, operating out of a generic town house in the northern Virginia suburbs of Washington DC. Donors Capital caters to those making donations of $1m or more.

Whitney Ball, chief executive of the Donors Trust told the Guardian that her organisation assured wealthy donors that their funds would never by diverted to liberal causes.

The funding stream far outstripped the support from more visible opponents of climate action such as the oil industry or the conservative billionaire Koch brothers. Photograph: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

The funding stream far outstripped the support from more visible opponents of climate action such as the oil industry or the conservative billionaire Koch brothers. Photograph: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

"We exist to help donors promote liberty which we understand to be limited government, personal responsibility, and free enterprise," she said in an interview.

By definition that means none of the money is going to end up with groups like Greenpeace, she said. "It won't be going to liberals."

Ball won't divulge names, but she said the stable of donors represents a wide range of opinion on the American right. Increasingly over the years, those conservative donors have been pushing funds towards organisations working to discredit climate science or block climate action.

Donors exhibit sharp differences of opinion on many issues, Ball said. They run the spectrum of conservative opinion, from social conservatives to libertarians. But in opposing mandatory cuts to greenhouse gas emissions, they found common ground.

"Are there both sides of an environmental issue? Probably not," she went on. "Here is the thing. If you look at libertarians, you tend to have a lot of differences on things like defence, immigration, drugs, the war, things like that compared to conservatives. When it comes to issues like the environment, if there are differences, they are not nearly as pronounced."

By 2010, the dark money amounted to $118m distributed to 102 thinktanks or action groups which have a record of denying the existence of a human factor in climate change, or opposing environmental regulations.

The money flowed to Washington thinktanks embedded in Republican party politics, obscure policy forums in Alaska and Tennessee, contrarian scientists at Harvard and lesser institutions, even to buy up DVDs of a film attacking Al Gore.

The ready stream of cash set off a conservative backlash against Barack Obama's environmental agenda that wrecked any chance of Congress taking action on climate change.

Graphic: climate denial funding

Graphic: climate denial funding

Those same groups are now mobilising against Obama's efforts to act on climate change in his second term. A top recipient of the secret funds on Wednesday put out a point-by-point critique of the climate content in the president's state of the union address.

And it was all done with a guarantee of complete anonymity for the donors who wished to remain hidden.

"The funding of the denial machine is becoming increasingly invisible to public scrutiny. It's also growing. Budgets for all these different groups are growing," said Kert Davies, research director of Greenpeace, which compiled the data on funding of the anti-climate groups using tax records.

"These groups are increasingly getting money from sources that are anonymous or untraceable. There is no transparency, no accountability for the money. There is no way to tell who is funding them," Davies said.

The trusts were established for the express purpose of managing donations to a host of conservative causes.

Such vehicles, called donor-advised funds, are not uncommon in America. They offer a number of advantages to wealthy donors. They are convenient, cheaper to run than a private foundation, offer tax breaks and are lawful.

That opposition hardened over the years, especially from the mid-2000s where the Greenpeace record shows a sharp spike in funds to the anti-climate cause.

In effect, the Donors Trust was bankrolling a movement, said Robert Brulle, a Drexel University sociologist who has extensively researched the networks of ultra-conservative donors.

"This is what I call the counter-movement, a large-scale effort that is an organised effort and that is part and parcel of the conservative movement in the United States " Brulle said. "We don't know where a lot of the money is coming from, but we do know that Donors Trust is just one example of the dark money flowing into this effort."

In his view, Brulle said: "Donors Trust is just the tip of a very big iceberg."

The rise of that movement is evident in the funding stream. In 2002, the two trusts raised less than $900,000 for the anti-climate cause. That was a fraction of what Exxon Mobil or the conservative oil billionaire Koch brothers donated to climate sceptic groups that year.

By 2010, the two Donor Trusts between them were channelling just under $30m to a host of conservative organisations opposing climate action or science. That accounted to 46% of all their grants to conservative causes, according to the Greenpeace analysis.

The funding stream far outstripped the support from more visible opponents of climate action such as the oil industry or the conservative billionaire Koch brothers, the records show. When it came to blocking action on the climate crisis, the obscure charity in the suburbs was outspending the Koch brothers by a factor of six to one.

"There is plenty of money coming from elsewhere," said John Mashey, a retired computer executive who has researched funding for climate contrarians. "Focusing on the Kochs gets things confused. You can not ignore the Kochs. They have their fingers in too many things, but they are not the only ones."

It is also possible the Kochs continued to fund their favourite projects using the anonymity offered by Donor Trust.

But the records suggest many other wealthy conservatives opened up their wallets to the anti-climate cause – an impression Ball wishes to stick.

She argued the media had overblown the Kochs support for conservative causes like climate contrarianism over the years. "It's so funny that on the right we think George Soros funds everything, and on the left you guys think it is the evil Koch brothers who are behind everything. It's just not true. If the Koch brothers didn't exist we would still have a very healthy organisation," Ball said.

Monday, 19 December 2011

'Freedom' an instrument of oppression

This bastardised libertarianism makes 'freedom' an instrument of oppression

It's the disguise used by those who wish to exploit without restraint, denying the need for the state to protect the 99%

Illustration by Daniel Pudles

Freedom: who could object? Yet this word is now used to justify a thousand forms of exploitation. Throughout the rightwing press and blogosphere, among thinktanks and governments, the word excuses every assault on the lives of the poor, every form of inequality and intrusion to which the 1% subject us. How did libertarianism, once a noble impulse, become synonymous with injustice?

In the name of freedom – freedom from regulation – the banks were permitted to wreck the economy. In the name of freedom, taxes for the super-rich are cut. In the name of freedom, companies lobby to drop the minimum wage and raise working hours. In the same cause, US insurers lobby Congress to thwart effective public healthcare; the government rips up our planning laws; big business trashes the biosphere. This is the freedom of the powerful to exploit the weak, the rich to exploit the poor.

Rightwing libertarianism recognises few legitimate constraints on the power to act, regardless of the impact on the lives of others. In the UK it is forcefully promoted by groups like the TaxPayers' Alliance, the Adam Smith Institute, the Institute of Economic Affairs, and Policy Exchange. Their concept of freedom looks to me like nothing but a justification for greed.

So why have we been been so slow to challenge this concept of liberty? I believe that one of the reasons is as follows. The great political conflict of our age – between neocons and the millionaires and corporations they support on one side, and social justice campaigners and environmentalists on the other – has been mischaracterised as a clash between negative and positive freedoms. These freedoms were most clearly defined by Isaiah Berlin in his essay of 1958, Two Concepts of Liberty. It is a work of beauty: reading it is like listening to a gloriously crafted piece of music. I will try not to mangle it too badly.

Put briefly and crudely, negative freedom is the freedom to be or to act without interference from other people. Positive freedom is freedom from inhibition: it's the power gained by transcending social or psychological constraints. Berlin explained how positive freedom had been abused by tyrannies, particularly by the Soviet Union. It portrayed its brutal governance as the empowerment of the people, who could achieve a higher freedom by subordinating themselves to a collective single will.

Rightwing libertarians claim that greens and social justice campaigners are closet communists trying to resurrect Soviet conceptions of positive freedom. In reality, the battle mostly consists of a clash between negative freedoms.

As Berlin noted: "No man's activity is so completely private as never to obstruct the lives of others in any way. 'Freedom for the pike is death for the minnows'." So, he argued, some people's freedom must sometimes be curtailed "to secure the freedom of others". In other words, your freedom to swing your fist ends where my nose begins. The negative freedom not to have our noses punched is the freedom that green and social justice campaigns, exemplified by the Occupy movement, exist to defend.

Berlin also shows that freedom can intrude on other values, such as justice, equality or human happiness. "If the liberty of myself or my class or nation depends on the misery of a number of other human beings, the system which promotes this is unjust and immoral." It follows that the state should impose legal restraints on freedoms that interfere with other people's freedoms – or on freedoms which conflict with justice and humanity.

These conflicts of negative freedom were summarised in one of the greatest poems of the 19th century, which could be seen as the founding document of British environmentalism. In The Fallen Elm, John Clare describes the felling of the tree he loved, presumably by his landlord, that grew beside his home. "Self-interest saw thee stand in freedom's ways / So thy old shadow must a tyrant be. / Thou'st heard the knave, abusing those in power, / Bawl freedom loud and then oppress the free."

The landlord was exercising his freedom to cut the tree down. In doing so, he was intruding on Clare's freedom to delight in the tree, whose existence enhanced his life. The landlord justifies this destruction by characterising the tree as an impediment to freedom – his freedom, which he conflates with the general liberty of humankind. Without the involvement of the state (which today might take the form of a tree preservation order) the powerful man could trample the pleasures of the powerless man. Clare then compares the felling of the tree with further intrusions on his liberty. "Such was thy ruin, music-making elm; / The right of freedom was to injure thine: / As thou wert served, so would they overwhelm / In freedom's name the little that is mine."

But rightwing libertarians do not recognise this conflict. They speak, like Clare's landlord, as if the same freedom affects everybody in the same way. They assert their freedom to pollute, exploit, even – among the gun nuts – to kill, as if these were fundamental human rights. They characterise any attempt to restrain them as tyranny. They refuse to see that there is a clash between the freedom of the pike and the freedom of the minnow.

Last week, on an internet radio channel called The Fifth Column, I debated climate change with Claire Fox of the Institute of Ideas, one of the rightwing libertarian groups that rose from the ashes of the Revolutionary Communist party. Fox is a feared interrogator on the BBC show The Moral Maze. Yet when I asked her a simple question – "do you accept that some people's freedoms intrude upon other people's freedoms?" – I saw an ideology shatter like a windscreen. I used the example of a Romanian lead-smelting plant I had visited in 2000, whose freedom to pollute is shortening the lives of its neighbours. Surely the plant should be regulated in order to enhance the negative freedoms – freedom from pollution, freedom from poisoning – of its neighbours? She tried several times to answer it, but nothing coherent emerged which would not send her crashing through the mirror of her philosophy.

Modern libertarianism is the disguise adopted by those who wish to exploit without restraint. It pretends that only the state intrudes on our liberties. It ignores the role of banks, corporations and the rich in making us less free. It denies the need for the state to curb them in order to protect the freedoms of weaker people. This bastardised, one-eyed philosophy is a con trick, whose promoters attempt to wrongfoot justice by pitching it against liberty. By this means they have turned "freedom" into an instrument of oppression.

Friday, 5 August 2011

UK's secret policy on torture revealed

Document shows intelligence officers instructed to weigh importance of information sought against pain inflicted

- Ian Cobain

- guardian.co.uk,

-

larger | smaller

larger | smaller

A number of men said they were questioned by MI5 and MI6 officers after being tortured at Guantánamo Bay. Photograph: Mark Wilson/Getty Images

A top-secret document revealing how MI6 and MI5 officers were allowed to extract information from prisoners being illegally tortured overseas has been seen by the Guardian.

The interrogation policy – details of which are believed to be too sensitive to be publicly released at the government inquiry into the UK's role in torture and rendition – instructed senior intelligence officers to weigh the importance of the information being sought against the amount of pain they expected a prisoner to suffer. It was operated by the British government for almost a decade.

A copy of the secret policy showed senior intelligence officers and ministers feared the British public could be at greater risk of a terrorist attack if Islamists became aware of its existence.

One section states: "If the possibility exists that information will be or has been obtained through the mistreatment of detainees, the negative consequences may include any potential adverse effects on national security if the fact of the agency seeking or accepting information in those circumstances were to be publicly revealed.

"For instance, it is possible that in some circumstances such a revelation could result in further radicalisation, leading to an increase in the threat from terrorism."

The policy adds that such a disclosure "could result in damage to the reputation of the agencies", and that this could undermine their effectiveness.

The fact that the interrogation policy document and other similar papers may not be made public during the inquiry into British complicity in torture and rendition has led to human rights groups and lawyers refusing to give evidence or attend any meetings with the inquiry team because it does not have "credibility or transparency".

The decision by 10 groups – including Liberty, Reprieve and Amnesty International – follows the publication of the inquiry's protocols, which show the final decision on whether material uncovered by the inquiry, led by Sir Peter Gibson, can be made public will rest with the cabinet secretary.

The inquiry will begin after a police investigation into torture allegations has been completed.

Some have criticised the appointment of Gibson, a retired judge, to head the inquiry because he previously served as the intelligence services commissioner, overseeing government ministers' use of a controversial power that permits them to "disapply" UK criminal and civil law in order to offer a degree of protection to British intelligence officers committing crimes overseas. The government denies there is a conflict of interest.

The protocols also stated that former detainees and their lawyers will not be able to question intelligence officials and that all evidence from current or former members of the security and intelligence agencies, below the level of head, will be heard in private.

The document seen by the Guardian shows how the secret interrogation policy operated until it was rewritten on the orders of the coalition government last July.

It also:

• Acknowledged that MI5 and MI6 officers could be in breach of both UK and international law by asking for information from prisoners held by overseas agencies known to use torture.

• Explained the need to obtain political cover for any potentially criminal act by consulting ministers beforehand.

The secret interrogation policy was first passed to MI5 and MI6 officers in Afghanistan in January 2002 to enable them to continue questioning prisoners whom they knew were being mistreated by members of the US military.

It was amended slightly later that year before being rewritten and expanded in 2004 after it became apparent that a significant number of British Muslims, radicalised by the invasion of Iraq, were planning attacks against the UK.

The policy was amended again in July 2006 during an investigation of a suspected plot to bring down airliners over the Atlantic.

Entitled "Agency policy on liaison with overseas security and intelligence services in relation to detainees who may be subject to mistreatment", it was given to intelligence officers handing over questions to be put to detainees.

Separate policy documents were issued for related matters, including intelligence officers conducting face-to-face interrogations.

The document set out the international and domestic law on torture, and explained that MI5 and MI6 do not "participate in, encourage or condone" either torture or inhuman or degrading treatment.

Intelligence officers were instructed not to carry out any action "which it is known" would result in torture. However, they could proceed when they foresaw "a real possibility their actions will result in an individual's mistreatment" as long as they first sought assurances from the overseas agency.

Even when such assurances were judged to be worthless, officers could be given permission to proceed despite the real possibility that they would committing a crime and that a prisoner or prisoners would be tortured.

"When, not withstanding any caveats or prior assurances, there is still considered to be a real possibility of mistreatment and therefore there is considered to be a risk that the agencies' actions could be judged to be unlawful, the actions may not be taken without authority at a senior level. In some cases, ministers may need to be consulted," the document said.

In deciding whether to give permission, senior MI5 and MI6 management "will balance the risk of mistreatment and the risk that the officer's actions could be judged to be unlawful against the need for the proposed action".

At this point, "the operational imperative for the proposed action, such as if the action involves passing

or obtaining life-saving intelligence" would be weighed against "the level of mistreatment anticipated and how likely those consequences are".

Ministers may be consulted over "particularly difficult cases", with the process of consulting being "designed to ensure that appropriate visibility and consideration of the risk of unlawful actions takes place". All such operations must remain completely secret or they could put UK interests and British lives at risk.

Disclosure of the contents of the document appears to help explain the high degree of sensitivity shown by ministers and former ministers after the Guardian became aware of its existence two years ago.

Tony Blair evaded a series of questions over the role he played in authorising changes to the instructions in 2004, while the former home secretary David Blunkett maintained it was potentially libellous even to ask him questions about the matter.

As foreign secretary, David Miliband told MPs the secret policy could never be made public as "nothing we publish must give succour to our enemies".

Blair, Blunkett and the former foreign secretary Jack Straw also declined to say whether or not they were aware that the instructions had led to a number of people being tortured.

The head of MI5, Jonathan Evans, said that, in the post 9/11 world, his officers would be derelict in their duty if they did not work with intelligence agencies in countries with poor human rights records, while his opposite number at MI6, Sir John Sawers, spoke of the "real, constant, operational dilemmas" involved in such relationships.

Others, however, are questioning whether – in the words of Ken Macdonald, a former director of public prosecutions, "Tony Blair's government was guilty of developing something close to a criminal policy".

The Intelligence and Security Committee, the group of parliamentarians appointed by the prime minister to assist with the oversight of the UK's intelligence agencies, is known to have examined the document while sitting in secret, but it is unclear what – if any – suggestions or complaints it made.

Paul Murphy, the Labour MP and former minister who chaired the committee in 2006, declined to answer questions about the matter.

A number of men, mostly British Muslims, have complained that they were questioned by MI5 and MI6 officers after being tortured by overseas intelligence officials in Pakistan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan and Guantánamo Bay. Some are known to have been detained at the suggestion of British intelligence officers.

Others say they were tortured in places such as Egypt, Dubai, Morocco and Syria, while being interrogated on the basis of information that could only have been supplied by the UK.

A number were subsequently convicted of serious terrorism offences or subjected to control orders.

Others returned to the UK and, after treatment, resumed their lives.

One is a businessman in Yorkshire, another a software designer living in Berkshire, and a third is a doctor practising on the south coast of England.

Some have brought civil proceedings against the British government, and a number have received compensation in out-of-court settlements, but others remain too scared to take legal action.

Scotland Yard has examined the possibility that one officer from MI5 and a second from MI6 committed criminal offences while extracting information from detainees overseas, and detectives are now conducting what is described as a "wider investigation into other potential criminal conduct".

A new set of instructions was drafted after last year's election, published on the orders of David Cameron, on the grounds that the coalition was "determined to resolve the problems of the past" and wished to give "greater clarity about what is and what is not acceptable in the future".

Human rights groups pointed to what they said were serious loopholes that could permit MI5 and MI6 officers to remain involved in the torture of prisoners overseas.

Last week, the high court heard a challenge to the legality of the new instructions, brought by the Equality and Human Rights Commission. Judgment is expected later in the year.

- guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)