Chris Mullin in The Guardian

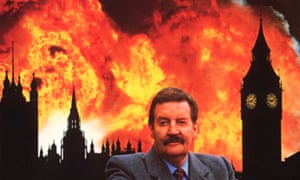

Publicity for the 1988 TV adaptation of Chris Mullin's book, A Very British Coup, with Ray McAnally as Prime Minister Harry Perkins. Photograph: British Film Institute

Monday 10 August 2015 18.38 BST

Monday 10 August 2015 18.38 BST

‘The news that Harry Perkins was to become prime minister went down very badly in the Athenaeum.” So ran the opening line from A Very British Coup. My 1982 novel was predicated on the surprise election of a leftwing Labour government led by a Sheffield steel worker that is then destabilised by the forces of darkness – a cabal of press barons in cahoots with M15, the CIA and with a little help from Labour insiders. It was, as the Guardian’s Simon Hoggart remarked at the time, “a delicious fantasy”.

It couldn’t happen now, could it? Successive election defeats and the triumph of New Labour have surely put paid for ever to the prospect of a leftwing Labourparty capable of winning an election. Or have they?

As it happens I long ago tapped out the first 5,000 words or so of a sequel, but fantasy or not, the astonishing rise of Jeremy Corbyn has given a new lease of life to the real-life possibility, however remote. At recent speaking engagements all available copies of the novel, which is still in print, were gobbled up within minutes. Repeatedly I was asked about the possibility of a Corbyn victory. Gently I pointed out that a party led by Corbyn, saintly and decent man that he is, was likely to be unelectable. Which only met with the riposte that since the other three candidates appear to be unelectable too, why not go for the real thing?

But delicious fantasy or not, let us for a moment suspend judgment and consider how the political establishment would react to a Corbyn victory.

One thing for sure, his honeymoon would be short. His first challenge would be the fact that he has very little support in the parliamentary Labour party. Appeals to loyalty are likely to fall on deaf ears, given his record as a serial dissident.

The good news for Corbyn is that, unlike in the 80s, defections are unlikely. A few people may retire earlier than intended, but I know of no one who thinks an SDP mark II would be a good idea, and the Liberal Democrats are not likely to be an attractive option for the foreseeable future. Corbyn’s principal problem would probably be the sullen indifference of parliamentary colleagues, rather than outright rebellion, though one can’t rule out a direct challenge in due course.

In politics, however, nothing is impossible. Today’s bogeymen can become tomorrow’s national treasures, albeit usually only after they have been rendered harmless. Suppose that Corbyn was to make it unscathed to the general election. Suppose, too, that the country was wearying of the Tories and their endless austerity, and that the polls had begun to predict that the gap between the two parties was closing. The Conservatives and all their friends in the media would, of course, attempt to organise mass hysteria – but it might not work.

Corbyn has several obvious advantages over mainstream rivals, such as the fact that he is an entirely different breed of politician to those the electorate has, fairly or not, come to despise. He is modest and untainted by any whiff of scandal, and has held broadly consistent views all his life. Unlike many leftists he is not given to ranting or rabble-rousing. On the contrary, he has conducted himself well so far. A sustained campaign on affordable housing might even win him friends across the board in the south-east of England, where Labour most needs votes.

Yes, stretching the political elastic to its limit, a Corbyn government is just about conceivable. If so, we are in Harry Perkins territory. The gloves would come off. The “coup” in the novel is that the election of Perkins is greeted by a huge run on sterling orchestrated by Treasury civil servants. A leading trade unionist is persuaded to organise a power industry strike, leading to blackouts. Perkins is finally brought down after being blackmailed by M15 over a relationship he once had with a woman who worked to the boss of a nuclear power company with whom he had dealings when he was secretary of state for energy.

In this case it is unlikely that M15 would interfere. It has its work cut out keeping track of Islamists, and has been cleaned up since the scandals of the 80s. (“We’ve cleared out a lot of dead wood,” a Tory home secretary once whispered to me.) The Americans are also unlikely to interfere unless their bases were threatened. Phasing out Trident wouldn’t bother them – they were never keen on our so-called independent deterrent.

Like that of Harry Perkins (and Harold Wilson), a Corbyn government would have problems with the bankers and the Treasury. These days,with a floating currency, runs on the pound are difficult to organise, but the deficit (which, despite their promises, the Tories won’t have abolished) and the balance of payments could be talked up, and a crisis easily organised.

The media barons would be a problem too. Opportunities for mischief would be legion. If it were up to me, rather than meet them head on, I’d offer the Murdochs a deal: a much larger share of Sky in exchange for relinquishing their British newspapers. You never know, it might wash.

The tricky moment would come when things started to go wrong, as they do for all governments. A few bad polls, bad economic news, electricity blackouts, a blockade of oil refineries … at that point, our beloved leader would face a challenge from someone within his own ranks, perhaps in league with the enemy. Yes, I think I am beginning to see my way to a sequel.