The two liberalisms - one offering genuine human freedom, the other entrapping humans in ruthless market mechanisms - are fundamentally in conflict writes Pankaj Misra in The Print

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s assertion last week that Western liberalism was obsolete provoked some strident rebuttals. A contemptuous silence might have been preferable, saving us the embarrassment of Boris Johnson invoking “our values,” or European Council President Donald Tusk claiming, against overwhelming evidence, that it was authoritarianism that was obsolete.

Even the Financial Times, to which Putin confided his views, was reduced to childishly asserting that “while America is no longer the shining city on the hill it once seemed, the world’s poor and oppressed still head overwhelmingly for the U.S. and western Europe” rather than Russia.

Such rhetoric from both sides felt like a rehash of the cold war, and with the same purpose: to conceal the failures and weaknesses of both systems.

One function of Russia’s communist tyranny in the past was to make its capitalist opponents look vastly better. Centrally planned command economies failed spectacularly, revealing that communists had no economic solution to the modern riddles of injustice and inequality, and were, furthermore, devastatingly blind to their own environmental depredations.

Wealth-creating capitalist economies, on the other hand, can hardly be said to have resolved those problems or made the world more inhabitable for future generations. Their advocates made extravagant promises of freedom, justice and prosperity after the collapse of communism, claiming that capitalism was the only viable model left standing at the End of History. Then their feckless experiments in free markets set the stage for the authoritarian movements and personalities that now dominate the news.

It should not be forgotten that the shock therapy of free markets administered to Russia during the 1990s caused widespread venality, chaos and mass suffering there, eventually boosting Putin to power. That’s why it won’t be enough to invoke, against Putin’s demagoguery, the most flattering definition of liberalism: as a guarantee of individual rights and civil liberties.

To be sure, the liberal tradition that affirms human freedom and dignity against the forces of autocracy, reactionary conservatism and social conformism is profoundly honorable, and ought to be always defended. But there is another liberalism that has been bound up since the 19th century with the fate of capitalist expansion, concerned with advancing the individual interests of the propertied and the shareholder. This is the liberalism, unconcerned with the common good, popularly denounced today as “neo-liberalism.”

In fact, the two liberalisms — one offering genuine human freedom, the other entrapping humans in impersonal and often ruthless market mechanisms — were always fundamentally in conflict. Still, they managed for a long time to coexist uneasily because the West’s expanding capitalist societies seemed capable of gradually extending social rights and economic benefits to all their citizens.

That unique capacity is today endangered by grotesque levels of oligarchic power and domestic inequality, as well as formidable challenges from economic powers such as China that the capitalist West had once dominated and exploited. In other words, modern history is no longer on the side of Western liberalism.

The devastating loss of its special status has exposed this central Western ideology to mockery from demagogues such as Putin and the Hungarian leader Viktor Orban. They’re joined by men of the hard right in the West who also zero in on liberals’ always vulnerable faith in cultural pluralism, denouncing immigrants and multiculturalism as well as sexual minorities.

In a much-circulated recent article, Sohrab Ahmari, the op-ed editor of the New York Post, complimented Donald Trump for shifting the national conversation from liberal notions of individual freedom to “order, continuity, and social cohesion.” But, as the intellectual historian Samuel Moyn put it last week, “the political system based on individual liberty and representative government doesn’t need to be celebrated or repudiated. It needs to be saved from itself” — from an obsession with “economic freedom that has undercut its own promise.”

Certainly, it won’t do to double down on shattered verities: to claim superior values, or to insist, as the Financial Times did, that “the superiority of private enterprise and free markets — at least within individual nations — in creating wealth is no longer seriously challenged.”

That seemingly last-minute qualifier, “at least within individual nations,” tries to conjure away the buffeting of national economies by opaque global forces. And it betrays the uncomfortable truth that, these days, even liberalism’s self-appointed defenders are not wholly convinced of their cause.

Perhaps, instead of mechanically asserting their superior status, they should examine their reflexively fanatical faith in market mechanisms. They should trace how the once-expansive liberal notion of individual freedom narrowed into a rigid principle of individual entrepreneurship and private wealth-creation. Indeed, such self-criticism has always defined the finest kind of liberalism. It is the best way today to renew an important tradition and convincingly defend it from its critics.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label injustice. Show all posts

Showing posts with label injustice. Show all posts

Tuesday, 2 July 2019

Tuesday, 19 March 2019

The best form of self-help is … a healthy dose of unhappiness

We’re seeking solace in greater numbers than ever. But we’re more likely to find it in reality than in positive thinking writes Tim Lott in The Guardian

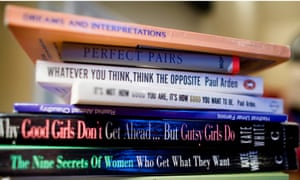

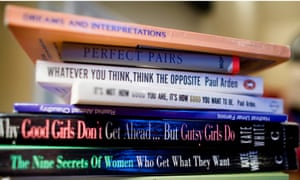

‘Self-help is almost as broad a genre as fiction.’ Photograph: Christopher Thomond/The Guardian

Booksellers have announced that sales of self-help books are at record levels. The cynics out there will sigh deeply in resignation, even though I suspect they don’t really have a clear idea of what a self-help book is (or could be). Then again, no one has much of an idea what a self-help book is. Is it popular psychology (such as Blink, or Daring Greatly)? Is it spirituality (The Power of Now, or A Course in Miracles)? Or a combination of both (The Road Less Travelled)?

Is it about “success” (The Seven Secrets of Successful People) or accumulating money (Mindful Money, or Think and Grow Rich)? Is Caitlin Moran’s How to Be a Woman self-help? Or the Essays of Montaigne?

Self-help – although I would prefer the term “self-curiosity” – is almost as broad a genre as fiction. Just as there are a lot of turkeys in literature, there are plenty in the self-help section, some of them remarkably successful despite – or because of – their idiocy. My personal nominations for the closest tosh-to-success correlation would include The Secret, You Can Heal Your Life and The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up – but that is narrowing down a very wide field.

In the minority are the intelligent and worthwhile books – but they can be found. I have enjoyed so-called pop psychology and spirituality books ever since I discovered Families and How to Survive Them by John Cleese and Robin Skynner in the 1980s, and Depression: The Way out of Your Prison by Dorothy Rowe at around the same time.

The Cleese book is a bit dated now, but Rowe’s set me off on a road that I am still following. She is what you might call a non-conforming Buddhist who introduced me to the writing of Alan Watts ( another non-conformer) whose The Meaning of Happiness and The Book have informed my life and worldview ever since.

The irony is that books of this particular stripe point you in a direction almost the opposite of most self-help books. Because, from How to Win Friends and Influence People through to The Power of Positive Thinking and Who Moved My Cheese?, “positive thinking” seems to be the unifying principle (although now partially supplanted by “mindfulness”).

The books I draw sustenance from contain the opposite wisdom. This isn’t negativity. It’s acceptance. Such thinking does not at first glance point you towards the destination of a happier life, which is probably why such tomes are far less popular than their bestselling peers. Yet these counter self-help books have a remarkable amount in common.

Most of them have Buddhism or Stoicism underpinning their thoughts. And they offer a different, and perhaps harder, road to happiness: not through effort, or willpower, or struggle with yourself, but through the forthright facing of facts that most of us prefer not to accept or think about.

Whether Seneca, or Nietzsche, Viktor Frankl or Rowe, Watts or Oliver Burkeman (The Antidote), or most recently Jordan B Peterson (12 Rules for Life), these thinkers all say much the same thing. Stop pretending. Get real.

It is not easy advice. Reality – now as ever – is unpopular, and for good reason. But the great thing about these self-help books is that, while giving sound advice, they are clear-eyed in acknowledging the truth: that happiness is not a given for anyone, there is no magic way of getting “it” – and that, crucially, pursuing it (or even believing in it), is one of the biggest obstacles to actually receiving it.

Such writers suggest the radical path to happiness comes from recognising the inevitability of unhappiness that comes as a result of the human birthright, that is, randomness, mortality, transitoriness, uncertainty and injustice. In other words, all the things we naturally shy away from and spend a huge amount of time and painful mental effort denying or trying not to think about.

Peterson perhaps puts it too strongly to say “life is catastrophe”, and the Buddha is out of date with “life is suffering”. Such strong medicine is understandably hard to take for many people in the comfortable and pleasure-seeking west. And despite what both Peterson and the Buddha say, not everyone suffers all that much.

Some people are just born happy or are lucky, or both, and are either incapable of feeling, or fortunate enough to never to have felt, a great deal in the way of pain or trauma. They are the people who never buy self-help books. But such individuals, I would suggest (although I can’t prove it), are the exception rather than the rule. The rest of us are simply pretending, to ourselves and to others, in order not to feel like failures.

But unhappiness is not failure. It is not pessimistic or morbid to say, for most of us, that life can be hard and that conflict is intrinsic to being and that mortality shadows our waking hours.

In fact it is life-affirming – because once you stop displacing these fears into everyday neuroses, life becomes tranquil, even when it is painful. And during those difficult times of loss and pain, to assert “this is the mixed package called life, and I embrace it in all its positive and negative aspects” shows real courage, rather than hiding in flickering, insubstantial fantasies of control, mysticism, virtue or wishful thinking.

That, as Dorothy Rowe says, is the real secret – that there is no secret.

Booksellers have announced that sales of self-help books are at record levels. The cynics out there will sigh deeply in resignation, even though I suspect they don’t really have a clear idea of what a self-help book is (or could be). Then again, no one has much of an idea what a self-help book is. Is it popular psychology (such as Blink, or Daring Greatly)? Is it spirituality (The Power of Now, or A Course in Miracles)? Or a combination of both (The Road Less Travelled)?

Is it about “success” (The Seven Secrets of Successful People) or accumulating money (Mindful Money, or Think and Grow Rich)? Is Caitlin Moran’s How to Be a Woman self-help? Or the Essays of Montaigne?

Self-help – although I would prefer the term “self-curiosity” – is almost as broad a genre as fiction. Just as there are a lot of turkeys in literature, there are plenty in the self-help section, some of them remarkably successful despite – or because of – their idiocy. My personal nominations for the closest tosh-to-success correlation would include The Secret, You Can Heal Your Life and The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up – but that is narrowing down a very wide field.

In the minority are the intelligent and worthwhile books – but they can be found. I have enjoyed so-called pop psychology and spirituality books ever since I discovered Families and How to Survive Them by John Cleese and Robin Skynner in the 1980s, and Depression: The Way out of Your Prison by Dorothy Rowe at around the same time.

The Cleese book is a bit dated now, but Rowe’s set me off on a road that I am still following. She is what you might call a non-conforming Buddhist who introduced me to the writing of Alan Watts ( another non-conformer) whose The Meaning of Happiness and The Book have informed my life and worldview ever since.

The irony is that books of this particular stripe point you in a direction almost the opposite of most self-help books. Because, from How to Win Friends and Influence People through to The Power of Positive Thinking and Who Moved My Cheese?, “positive thinking” seems to be the unifying principle (although now partially supplanted by “mindfulness”).

The books I draw sustenance from contain the opposite wisdom. This isn’t negativity. It’s acceptance. Such thinking does not at first glance point you towards the destination of a happier life, which is probably why such tomes are far less popular than their bestselling peers. Yet these counter self-help books have a remarkable amount in common.

Most of them have Buddhism or Stoicism underpinning their thoughts. And they offer a different, and perhaps harder, road to happiness: not through effort, or willpower, or struggle with yourself, but through the forthright facing of facts that most of us prefer not to accept or think about.

Whether Seneca, or Nietzsche, Viktor Frankl or Rowe, Watts or Oliver Burkeman (The Antidote), or most recently Jordan B Peterson (12 Rules for Life), these thinkers all say much the same thing. Stop pretending. Get real.

It is not easy advice. Reality – now as ever – is unpopular, and for good reason. But the great thing about these self-help books is that, while giving sound advice, they are clear-eyed in acknowledging the truth: that happiness is not a given for anyone, there is no magic way of getting “it” – and that, crucially, pursuing it (or even believing in it), is one of the biggest obstacles to actually receiving it.

Such writers suggest the radical path to happiness comes from recognising the inevitability of unhappiness that comes as a result of the human birthright, that is, randomness, mortality, transitoriness, uncertainty and injustice. In other words, all the things we naturally shy away from and spend a huge amount of time and painful mental effort denying or trying not to think about.

Peterson perhaps puts it too strongly to say “life is catastrophe”, and the Buddha is out of date with “life is suffering”. Such strong medicine is understandably hard to take for many people in the comfortable and pleasure-seeking west. And despite what both Peterson and the Buddha say, not everyone suffers all that much.

Some people are just born happy or are lucky, or both, and are either incapable of feeling, or fortunate enough to never to have felt, a great deal in the way of pain or trauma. They are the people who never buy self-help books. But such individuals, I would suggest (although I can’t prove it), are the exception rather than the rule. The rest of us are simply pretending, to ourselves and to others, in order not to feel like failures.

But unhappiness is not failure. It is not pessimistic or morbid to say, for most of us, that life can be hard and that conflict is intrinsic to being and that mortality shadows our waking hours.

In fact it is life-affirming – because once you stop displacing these fears into everyday neuroses, life becomes tranquil, even when it is painful. And during those difficult times of loss and pain, to assert “this is the mixed package called life, and I embrace it in all its positive and negative aspects” shows real courage, rather than hiding in flickering, insubstantial fantasies of control, mysticism, virtue or wishful thinking.

That, as Dorothy Rowe says, is the real secret – that there is no secret.

Tuesday, 26 May 2015

A Canadian's views on India

Tarek Fatah chats about his four-months visit to Hindustan - Bilatakalluf with Tahir Gora Ep10

Bilatakaluf with Tahir Gora TAGTV EP 07 - Is MQM victim or part of establishment?

Wednesday, 26 March 2014

Inherited wealth is an injustice. Let's end it

Inheritance, which rewards the wealthy for doing nothing, is once again becoming a key route to riches – just as it was in the Victorian era

'The transfer of wealth between generations allows access to privileges that are otherwise beyond reach.' Photograph: Cultura Creative (RF) / Alamy/Alamy

Inherited wealth is the great taboo of British politics. Nobody likes to talk about it, but it determines a huge number of outcomes: from participation in public life, to access to education, to the ability to save or purchase property. When David Cameron recently promised to raise the threshold for inheritance tax to £1m and praised "people who have worked hard and saved", he is singing from the hymn sheet of inherited inequality: it is, after all, easier to save if you inherit substantial sums to squirrel away, or if you can lock money in property that is virtually guaranteed to offer huge returns. Hard work has very little to do with it.

In 2010-11, the most recent period for which we have figures, 15,584 estates of 259,989 notified for probate paid inheritance tax. That is approximately 3% of all deaths that year. Already, inheritance tax is paid by a tiny fraction of all estates. The asset composition of these estates remains stable over time, with property composing about 50% of taxable estates; a disproportionate number of these are located in London and the south-east, reflecting the rocketing house prices in that corner of the country. The "nil-rate threshold" – the value under which inherited wealth is untouched by tax – currently stands at £325,000, frozen since April 2009. But that's only half the story. Since 2007, it has been possible for spouses to transfer their unused nil-rate band allowance to their surviving partner. This has lifted many estates in the £300-500,000 band out of inheritance tax altogether: at this point we are beginning to talk about substantial, indeed life-altering, sums of money.

Beyond these key figures lies a hinterland of tax-minimisation strategies through which assets can be exempted from tax, including various types of trust and business property relief. Despite nominal efforts to curb this kind of minimisation, there remains a booming market in financial advice tailored to avoidance. The knock-on effects of this minimisation are huge: it permits further concentration of wealth in the hands of those who already possess it, rewarding those cunning enough to avoid taxation, and cushioning their children with an influx of unearned wealth. There are obvious uses to which this can be put: paying off student loans early, thus avoiding interest, investing in buy-to-let property, or high-return financial products. It permits the children of the middle classes to sustain themselves through unpaid internships or unfunded study into secure middle-class careers, while locking these off from those without such resources. Given the chancellor's recent changes to pensions, the flow of cash into property as a secure income stream for the already wealthy is only likely to increase. Again, despite the rhetoric, this has little to do with hard work, but the preservation of wealth gaps between classes.

Why do we permit this? The transfer of wealth between generations is an injustice: it is a reward for no work, and a form of access to privileges that are otherwise beyond reach. Professor Thomas Piketty, in his new book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, makes the argument that, after a social-democratic blip in the middle of the last century, inheritance is once again becoming the key route to wealth. Piketty argues that if wealth is concentrated and the return on capital is higher than the economy's growth rate, inherited wealth will grow more rapidly than that stemming from work. This returns us to the terrain of Balzac and Austen, where the road to financial security is to target those who already possess wealth and, where possible, marry them. The data Piketty analyses – a huge and comprehensive set – suggests that the proportion of people receiving a sum in inheritance larger than the lifetime earnings of the bottom 50% is set to return to 19th-century levels in the next couple of decades. Pleasant news for our neo-Victorian government; less pleasant for the rest of us, and a disaster for anyone who cares about inequality.

It is difficult to justify inherited wealth from anything other than a class-partisan position. It is the point where the already threadbare veil of "meritocracy" falls off to reveal a fiscal system designed to reward already concentrated pots of wealth. Far from a Keynesian "euthanasia of the rentier", we are seeing the triumph of a rentier economy: in such conditions, rather than further accumulation by the sons and daughters of the wealthy, we should instead demand an end to inherited wealth entirely.

Sunday, 22 December 2013

Animal Farm - A Tale of two women

Meghnad Desai in the Indian Express

India's reaction to the arrest of Devyani Khobragade has been over the top. From a safe distance, the Indian political and diplomatic establishment was ready to almost declare war on America. The various past 'insults' have been detailed. Past ambassadors have thronged to TV channels to recount their experiences. India is about to retaliate and take away the rights and privileges of US diplomats.

India's reaction to the arrest of Devyani Khobragade has been over the top. From a safe distance, the Indian political and diplomatic establishment was ready to almost declare war on America. The various past 'insults' have been detailed. Past ambassadors have thronged to TV channels to recount their experiences. India is about to retaliate and take away the rights and privileges of US diplomats.

All this and what for? The arrest of a person who is consular appointment but who is charged with some criminal activities. None of those activities pertains to her job as a diplomat for India in the US. They concern the payment and treatment of her domestic staff, another Indian woman. In our rush to defend Devyani Khobragade, we forget the plight of Sangeeta Richard. Which is natural because one is IFS and another merely a domestic servant. What rights could a domestic have in India let alone in New York? She should have been grateful that she got this fantastic opportunity to go and serve in Khobragade's household looking after her children at Rs 30,000 per month with board and lodging.

The realities of the situation are otherwise. As the US legal documents in this case show, Rs 30,000 per month is just $3.31 per hour on the generous calculation that she worked only 40 hours a week. In the visa application the salary was given not as $573.07 per month (which the Rs 30,000 would have amounted to in the days of the strong rupee) but $4,500. Richard was instructed to lie about her salary to get the visa. Thus Khobragade knowingly falsified an official document. But also paying only $3.31 per hour amounts to wage slavery as that is below the minimum wage. Since the declared salary was seven times higher than what Richard was paid, imagine how far below the minimum wage her salary was.

The American legal submission is worth reading as it is very detailed, though somewhat clothed in legalese. The fact remains that Khobragade is charged with something which can merit 15 years of imprisonment. Employing someone below minimum wage (having stated that you will not do so in the visa application) is an offence. It is not part of her diplomatic activity. Human rights of one Indian citizen have been violated by an Indian IFS official. No one in Parliament raises a word about that. Khobragade may be a Dalit (though from the creamy layer as she owns flats in the Adarsh complex in Mumbai), but Richard may belong to a Scheduled Tribe, so there is no 'lower than thou' kudos there.

US Marshall Service (USMS) personnel are not the friendliest of people, especially when they are arresting someone they think is a criminal. Papers show that the Americans were aware of Khobragade's diplomatic status, but concluded that her status was irrelevant to her crime. Still the USMS should not have strip-searched her since her crime involved no violence. She was unlikely to be carrying weapons. Nor should she have to be swabbed as there was no evidence of drug abuse. The apology has to be about the manner of arrest but not about the fact that she will be proceeded against.

The lesson is that before the entire establishment lurches into a hysteria of self-righteousness, we should ask whether there is substance to the story. From the statements of various retired diplomats, it would seem the government of India knows about this practice of falsifying visa documents and connives in it. It also shows that the government is very mean in the amount it is willing to pay its officers abroad to enjoy the sort of lifestyle they enjoy at home. If it costs seven times as much to have a servant in New York as in Delhi, either pay that much or tell the diplomats they have to do without home help, as most Americans do.

The stance India took was not a show of strength but one of petulance. The government admitted Khobragade's guilt when they transferred her to the UN. The injustice done to Richard and no doubt many other maid servants employed by IFS staff abroad still remains to be addressed.

Tell-Tale Charges

Sangeeta Richard’s husband Phillip in a petition to Delhi HC

The charges, culled from phone conversations he had with Sangeeta, cast Devyani in a somewhat different light, more a perpetrator than a victim. Phillip accuses her of treating his wife “like a slave”, making her work from 6 am to 11 pm everyday, “often without breaks”, and pleads for her to be punished. Even though she was entitled to a day off, the petition claims, she was made to work similar hours on Sunday, with a break of two hours for her to go to church. “She was even asked to stop eating if she had some work to do,” says Tariq Adeeb, Phillip’s advocate. Devyani reportedly also “confiscated” Sangeeta’s passport after the duo’s arrival in November last year “telling her that the original has to be submitted in the ministry”. “This was just a subterfuge to illegally keep Sangeeta’s passport,” the petition reads.

As outrage over Devyani’s arrest and her maltreatment grew, there was little thought for Sangeeta. “If she couldn’t afford a help in New York, she should not have taken one. We have to give the work of a domestic help its due dignity,” says Rishi Kant, who works for Shakti Vahini, a Delhi-based organisation that works with domestic helps. New York-based Preet Bharara, the prosecutor in this case, also asked pointedly, “One wonders why there is so much outrage about the alleged treatment of the Indian national accused of perpetrating these acts, but precious little outrage about the alleged treatment of the Indian victim and her spouse?”

Weeks after her arrival, Sangeeta complained to Phillip about her “miserable work condition” and asked her employer to relieve her and have her sent to India. On June 23, a day after telling Phillip of her constant harassment, she went out to buy groceries. And has not returned since. Phillip even accuses Devyani of deducting Rs 10,000 from her salary when Sangeeta fell ill whereas her contract promised “full medical care”. His plea was dismissed on July 19, according to Adeeb, because the high court claimed “no jurisdiction on a crime committed on foreign soil”.

Devyani stands accused by US authorities of “visa fraud” and giving “false information”. While submitting details for a visa for Sangeeta, she clearly stated she would be paid $9.75 per hour, in line with the minimum wage requirements, but alongside she had executed a second contract that was signed by the two and concealed from US authorities. According to this, she would be paid a maximum of Rs 30,000 per month or $3.31 per hour.

The US complaint, based on statements by Sangeeta, even accuses the diplomat of instructing her not to mention being paid Rs 30,000 at the visa interview and claim that she would work stipulated hours. Phillip’s petition also adds that Devyani “took the signature of Sangeeta” on the second contract at the airport two hours before their departure. The diplomat’s father, Uttam Khobragade, has refuted these charges, claiming that Sangeeta was being paid $8.75, of which Rs 30,000 was being sent to her husband every month. They have even accused Sangeeta of “extortion”, claiming she asked for $10,000, a regular passport—hers was an official one secured for her by her employer—and immigration assistance. At a press conference in Mumbai, Devyani’s father reiterated that stand. “We paid her according to the minimum wage. Sangeeta seems to have used Devyani to go to the US,” he said. With Sangeeta herself still not having given her side of the story, the last word on ‘Khobragate’ is still awaited.

-------

-------

Taxpayer picked up $75,000 tab for deal between another diplomat, his maid last year

Amitav Ranjan in Indian Express : New Delhi, Sun Dec 22 2013, 09:13 hrs

It could ultimately fall on the Indian taxpayer to bail out Devyani Khobragade, the diplomat accused of underpaying her domestic help and falsifying documents to get the maid into the US.

A complaint of a similar nature against another Indian diplomat by his maid two years ago in New York had resulted in an out-of-court settlement, with the government of India footing the bill.

In December 2012, the Ministry of Finance approved the payment of $75,000 from the budget of the Ministry of External Affairs to a "former domestic assistant" who had filed a lawsuit against India's consul-general in New York, Prabhu Dayal, alleging inhuman treatment.

The settlement agreement stipulated that the deal's details would not be disclosed, or discussed with the media.

The maid, Santosh Bhardwaj, filed a lawsuit in June 2011, accusing Dayal of sexual harassment and demanding a massage from her in January 2010.

The complainant accused Dayal and his wife of making her work for long hours for $300 a month, taking away her passport, and forcing her to sleep in a storage closet. Bhardwaj demanded over $250,000 in damages and relief, but subsequently withdrew her charge of sexual harassment against the consul-general.

Dayal said the maid had run away because he had refused to let her work outside the consulate, which would have allowed her to make some extra money, but would have violated visa rules.

He denied having treated Bhardwaj badly, and said that she lived very comfortably in her own furnished room in the consulate, and was paid according to the rules.

Following an out-of-court settlement advised by the US court, the MEA, on November 21, 2012, sought Finance's sanction for $ 75,000 to settle the matter, official sources said. The argument was that the government should pay, because the consul-general had hired the maid in line with the government scheme of allowing servants during the overseas postings of diplomats.

The MEA argued that the allegation against Dayal was false, and he had been caught in blackmail resorted to by domestic helps in collusion with NGOs in the US. It backed the out-of-court settlement, saying that fighting a long legal battle would be costlier.

With the approval of the Department of Expenditure, the money was paid from the MEA's miscellaneous head, the sources said.

Despite several attempts, Prabhu Dayal, who retired from service after his New York stint, could not be traced for a comment. His whereabouts were not available even in the retired diplomats' directory.

-----

Poverty of the Indian Elite

Saba Naqvi in Outlook India

India cares about its honour. But its missions abroad apparently do not care about the rights of Indian labour. Consider the manner in which they have responded to the arrest and strip-search of India’s deputy consul-general in New York, Devyani Khobragade. The response has overwhelmingly been of a cosy clique out to protect one of its own. One could be forgiven for thinking that the mandate of the foreign service is to protect itself at the cost of the country’s less fortunate citizens.

In pursuit of that end, retired and serving officers have pulled out every argument about diplomatic immunity and Vienna Convention and gone ballistic against the US, a nation before which they usually bend quite happily and show no spine when real issues are at stake. Now, however, it has been verbal warfare for some days now. It helped that the media was also anxious to wrap up the entire story about Devyani Khobragade in the national flag and posit it as an assault on India’s dignity.

This is actually quite a bogus position if we believe in fundamental human rights. Why is no one talking about the rights of the domestic help (in the US or India)? Is the maid not Indian, only the diplomat is? And do we think that not only is it okay to pay people below the minimum wage in India but that the “right” should be extended to a certain class of Indians when they travel abroad? After all, the way this debate has been framed would suggest that middle-class Indians have some sort of divine right to domestic help—so much so that it is quite kosher for the nation’s diplomats (meant to uphold the law) to sign false documents about the salary they pay for service in their homes?

Is it being crazy or “anti-national” to wonder if the diplomat herself did not assault the national honour when she indulged in falsification, perjury and fraud? For, what kind of honour are we talking about when power and prestige seem to come from chest-thumping and bullying and has little to do with any humanitarian principle! What has become shockingly clear through this entire episode is that India has long abandoned its role as a nation that would speak for the less fortunate. For there was actually a time when India was a moral force in the world. Then the world extended real respect to its leaders and ideas. A “regret” by John Kerry after an almighty tantrum is not a reflection of that sort of respect.

Certainly, Devyani’s arrest should have been handled with greater sensitivity. Equally, it is true that the US applies different principles to itself and the rest of the world. But in the Devyani episode, we too have violated the spirit of one fundamental principle. For, a nation like India, with its millions who live on a subsistence wage, should be endorsing the imposition of a minimum wage. Instead, we have taken the position that seems to suggest that because our diplomats can’t afford to pay the US minimum wage, we expect the host nation to look the other way because heck, we are Indians and we need our maids and nannies! It’s actually quite pathetic that after having taken such a morally bankrupt position, we would subsequently gloat and say, see we showed them, Kerry called and apologised.

In this rather sorry tale, the maid, the other Indian in the story, has been mostly forgotten. If she is remembered, it is because the establishment has in an attempt to slander Sangeeta Richard, raised questions about her motives and even suggested that she is part of an “evangelical” conspiracy against India that operates in the US (the same conspiracy that denies Narendra Modi a visa, says one commentator).

Because labour is cheap in India and poverty rampant, certain wage laws have been enacted to protect the poor. Public servants should be held to a higher standard both in India and outside. The babus of the foreign service cannot hide behind diplomatic immunity and hold cheap Indian labour hostage to their needs.

Devyani now has a job in the UN, presumably with maids in tow. She also has a flat in the Adarsh Society in Mumbai besides 30 acres of farmland in Maharashtra that she inherited, a 5,000 sq ft plot in Alibaug and a plot in Noida. If she could not live without a maid, she should have paid the minimum wage in the US. Sangeeta Richard has complained about Devyani taking away her basic rights and treating her “like a slave”. Both as an Indian citizen and as a citizen of a world governed by ideas of justice and equality, Sangeeta has every right to seek a better life.

-----

The Other Side of the Story

Outlook India

Sangeeta Richard’s husband Phillip in a petition to Delhi HC

- ”The treatment of Sangeeta by Devyani Khobragade is tantamount to keeping a person in slavery-like conditions or keeping a person in bondage.”

- ”Even though the contract stipulated that Sunday would be an off-day she worked from 6 am to 11 pm, minus 2 hours for church even on Sunday. She worked from 6 am to 11 pm on Saturday as well.”

- “Uttam Khobragade called Sangeeta’s family several times and threatened them that they would have to face dire consequences if she complains and that he would ruin their future, get them abducted and frame false charges of drugs against them.”

- ”At the immigration office, Devyani falsely accused Sangeeta of theft, in front of the US Immigration Officer. Sangeeta asked what it was she had stolen. Devyani could not say and threatened her saying that she will come to know when she returns home.”

- ”My mother used to sound unhappy whenever she talked to us on phone.She asked Devyani to send her back to India but Devyani refused her request.”

- “Uttam Khobragade forced police to come to our house at night around 11 pm. There were 5 policemen. From that day onwards police has started calling my father, my brother and me as well... He said to my father that he would destroy our future and not let my father continue with his job anymore.”

- ”We no more feel safe in our own house because of the phone calls we are getting and the words that Uttam Khobragade has said to my father. We really need your help to get out of all this trouble. It is like a mental torture on my family. PLEASE HELP US.”

***

Much has been said on ‘Khobragate’ but almost none of it has come from Sangeeta Richard, the help, or her family. Though she is in the US, few know about her whereabouts; neither has she issued any statement after walking out of her employer’s house in June. Even her husband and two children—a son and daughter—are now in the US, having flown out of New Delhi days before Devyani Khobragade’s arrest, and remain incommunicado. In this context, one crucial document that adds fresh detail to the prevailing narrative is the petition her husband Phillip Richard had filed in the Delhi High Court in July this year.The charges, culled from phone conversations he had with Sangeeta, cast Devyani in a somewhat different light, more a perpetrator than a victim. Phillip accuses her of treating his wife “like a slave”, making her work from 6 am to 11 pm everyday, “often without breaks”, and pleads for her to be punished. Even though she was entitled to a day off, the petition claims, she was made to work similar hours on Sunday, with a break of two hours for her to go to church. “She was even asked to stop eating if she had some work to do,” says Tariq Adeeb, Phillip’s advocate. Devyani reportedly also “confiscated” Sangeeta’s passport after the duo’s arrival in November last year “telling her that the original has to be submitted in the ministry”. “This was just a subterfuge to illegally keep Sangeeta’s passport,” the petition reads.

|

As outrage over Devyani’s arrest and her maltreatment grew, there was little thought for Sangeeta. “If she couldn’t afford a help in New York, she should not have taken one. We have to give the work of a domestic help its due dignity,” says Rishi Kant, who works for Shakti Vahini, a Delhi-based organisation that works with domestic helps. New York-based Preet Bharara, the prosecutor in this case, also asked pointedly, “One wonders why there is so much outrage about the alleged treatment of the Indian national accused of perpetrating these acts, but precious little outrage about the alleged treatment of the Indian victim and her spouse?”

Weeks after her arrival, Sangeeta complained to Phillip about her “miserable work condition” and asked her employer to relieve her and have her sent to India. On June 23, a day after telling Phillip of her constant harassment, she went out to buy groceries. And has not returned since. Phillip even accuses Devyani of deducting Rs 10,000 from her salary when Sangeeta fell ill whereas her contract promised “full medical care”. His plea was dismissed on July 19, according to Adeeb, because the high court claimed “no jurisdiction on a crime committed on foreign soil”.

Devyani stands accused by US authorities of “visa fraud” and giving “false information”. While submitting details for a visa for Sangeeta, she clearly stated she would be paid $9.75 per hour, in line with the minimum wage requirements, but alongside she had executed a second contract that was signed by the two and concealed from US authorities. According to this, she would be paid a maximum of Rs 30,000 per month or $3.31 per hour.

The US complaint, based on statements by Sangeeta, even accuses the diplomat of instructing her not to mention being paid Rs 30,000 at the visa interview and claim that she would work stipulated hours. Phillip’s petition also adds that Devyani “took the signature of Sangeeta” on the second contract at the airport two hours before their departure. The diplomat’s father, Uttam Khobragade, has refuted these charges, claiming that Sangeeta was being paid $8.75, of which Rs 30,000 was being sent to her husband every month. They have even accused Sangeeta of “extortion”, claiming she asked for $10,000, a regular passport—hers was an official one secured for her by her employer—and immigration assistance. At a press conference in Mumbai, Devyani’s father reiterated that stand. “We paid her according to the minimum wage. Sangeeta seems to have used Devyani to go to the US,” he said. With Sangeeta herself still not having given her side of the story, the last word on ‘Khobragate’ is still awaited.

-------

A tale of two citizens

RUCHIRA GUPTA in THE HINDUIn the Khobragade case, India had two standards: one for what a middle-class woman needs and feels and another for what a working-class woman needs and feels

India has two citizens, not one — Devyani Khobragade and Sangeeta Richard. India needs to stand by both. Both are looking for protection from unfair treatment. However, one is being blamed for speaking up while the other has been turned into a heroine, whose honour is tied up with India’s honour. Ms. Richard not only had to work for Ms. Khobragade in New York for less than the legal minimum wage but was also forced to sign documents saying she was earning more. When she objected and left her employment, her family in Delhi was threatened and cases were filed against her in a Delhi court for flouting her visa conditions.

Ms. Khobragade was picked up outside her daughter’s school for not paying Ms. Richard the legal minimum wage. She was humiliatingly handcuffed and strip-searched — a violation of the Vienna Convention, which lays down the guidelines for how diplomats should be treated.

While India has rightfully objected to the treatment of its diplomat, it needs to address the fact that she broke the law of the host country she was posted to.

The diplomat not only did not pay legal wages, she also falsified documents and then tried to intimidate the victim’s family by filing a case in the Delhi High Court. If Ms. Richard “stole” money and a phone as the Indian embassy press release says, then a police case ought to have been filed in New York and not Delhi, a city where Ms. Khobragade has connections and influence.

The victim and her family were hiding in fear of retaliation by Ms. Khobragade’s family and the government till they left Delhi for New York.

Both women are wives, daughters and mothers, and both are concerned about their families. While the government has expressed concern about the trauma of one woman’s daughter and family, there is only anger against the other woman’s family. One is a working-class woman, while the other is a well-placed government official and millionaire.

This class divide has influenced our reactions to both women. Our anger against Ms. Richard is based on our own sense of entitlement over the poor and the working class. We feel betrayed when they ask for anything that we have not conferred on them out of the “largeness” of our hearts.

We have two standards for what a middle-class woman needs and feels and what a working-class woman needs and feels. While we are quick to point out that the salaries of our foreign diplomats need to be raised so that they can afford to pay their domestic help according to U.S. standards, we omit to note that we have no minimum wages in India for our own domestic help. Only two States in India, Tamil Nadu and Kerala have any legislative protection for domestic workers. Routinely, domestic helps in India are exploited in terms of no. of working hours, pay, living conditions and leave. Live-in help in middle-class India usually work round the clock.

Perhaps that is why Ms. Khobragade did not feel she was doing anything wrong in breaking the U.S. law. Her outlook was conditioned and normalised by the working conditions of domestic help in India.

Standing by the weak

Empathy is a very revolutionary emotion. It is high time that the Indian government addressed the labour conditions of millions of domestic workers in India through legislation and fixing accountability on those who exploit them. Patriotism is not just about standing by the rich and powerful but about standing by Gandhi’s “last” (the poorest and weakest) individual or Ambedkar’s Dalit (oppressed) person. When Bharatiya Janata Party leader Yashwant Sinha calls for the government to take action against gay U.S. diplomats under Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code which criminalises homosexuality, or when Samajwadi Party’s Azam Khan offers a seat in his constituency to Ms. Khobragade, or former Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Mayawati says that the Indian government was slow in reacting to Ms. Khobragade’s arrest because she was a Dalit, they are ignoring the very ethos of Indian democracy on which our nation rests.

Empathy is a very revolutionary emotion. It is high time that the Indian government addressed the labour conditions of millions of domestic workers in India through legislation and fixing accountability on those who exploit them. Patriotism is not just about standing by the rich and powerful but about standing by Gandhi’s “last” (the poorest and weakest) individual or Ambedkar’s Dalit (oppressed) person. When Bharatiya Janata Party leader Yashwant Sinha calls for the government to take action against gay U.S. diplomats under Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code which criminalises homosexuality, or when Samajwadi Party’s Azam Khan offers a seat in his constituency to Ms. Khobragade, or former Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Mayawati says that the Indian government was slow in reacting to Ms. Khobragade’s arrest because she was a Dalit, they are ignoring the very ethos of Indian democracy on which our nation rests.

India has a moral standing in the world as the country that won independence from British colonialism through non-violence. We demonstrated to the world that the means are as important as the end. Once again, when we take the moral high ground with the U.S., we can only do so if we stand by all the “oppressed” and not just one of them.

-----

-----

An abuse of immunity?

- DEEPAK RAJU

- RUKMINI DAS in THE HINDU

Notwithstanding the several privileges and immunities Indian diplomats and consular officers are entitled to, they have a corresponding duty under the 1961 Convention and the 1963 Convention to respect the laws and regulations of the host State

The arrest of Indian Deputy Consul-General Devyani Khobragade in New York and the alleged mistreatment she faced have resulted in a diplomatic row between India and the United States. The Indian stance, after initial assertions that she enjoyed “diplomatic status” and that she should not have been arrested, now appears to focus on the manner of her arrest and her subsequent treatment. The U.S. has sought to justify the arrest on the grounds that the proceedings do not relate to Ms. Khobragade’s official acts, and has asserted that it followed the “standard procedure” in relation to her treatment. On the diplomatic front, India is reported to have initiated some tough measures, including the removal of security barriers around the U.S. Embassy in Delhi.

Question of immunity

At the outset, it is important to draw a distinction between diplomatic agents of states and consular staff. While the 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations covers the privileges and immunities of diplomatic agents, the treatment that consular staff are entitled to is laid down in the 1963 Vienna Convention on Consular Relations. As the Deputy Consul-General at the Indian Consulate in New York, Ms. Khobragade was, at the time of her arrest, a member of consular staff, and not a diplomat.

At the outset, it is important to draw a distinction between diplomatic agents of states and consular staff. While the 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations covers the privileges and immunities of diplomatic agents, the treatment that consular staff are entitled to is laid down in the 1963 Vienna Convention on Consular Relations. As the Deputy Consul-General at the Indian Consulate in New York, Ms. Khobragade was, at the time of her arrest, a member of consular staff, and not a diplomat.

Unlike the 1961 Convention, which vests diplomatic agents with absolute immunity from arrest, the 1963 Convention states that “Consular officers shall not be liable to arrest or detention pending trial, except in the case of a grave crime and pursuant to a decision by the competent judicial authority” (Article 41(1)). Article 43 of the Convention goes on to vest consular officers with immunity from jurisdiction of the receiving State in respect of official acts.

It is evident that the allegations against Ms. Khobragade relate to her personal and not to her official acts. This means that she is not immune from the jurisdiction of U.S. courts in relation to this allegation. However, this in itself does not render the arrest legal. There may be situations where a country may have jurisdiction to try an offence, but an arrest would violate international law. An Indian domestic law analogy may be one where the police station has jurisdiction to investigate an alleged offence, a magistrate’s court may have the power to try the case, and yet an arrest may be illegal due to various reasons like the lack of a warrant where required, or arrest of a woman after sunset. Similarly, for Ms. Khobragade’s arrest to be legal, in addition to the U.S. possessing jurisdiction to try her for the offence, it needs to be established that the conditions laid out in Article 41(1) are satisfied: (i) that her arrest relates to a “grave offence” and (ii) her arrest was pursuant to a decision by a competent judicial authority.

The 1963 Convention does not define what qualifies as a “grave offence.” However, the rejection of an initial draft that suggested that arrest be restricted to offences that carry a maximum sentence of five years or more indicates that the Convention leaves it to each State to determine, under its own domestic law, whether an offence amounts to a “grave” one. The charges that have been levelled against Ms. Khobragade are categorised as felonies in U.S. law. This may be sufficient to meet the requirement of a “grave offence.”

As per the documents published in The Hindu, her arrest was pursuant to a warrant issued by Hon. Debra Freeman, United States Magistrate Judge for the southern District of New York, a judicial authority. Thus, both the requirements imposed by the 1963 Convention for the arrest appear to have been met.

Even if the arrest was legal, her treatment including handcuffing and a strip-search could amount to violations of Article 41(3) which requires that criminal proceedings against a consular officer be conducted “with the respect due to [her] by reason of [her] official position.”

In sum, the arrest itself appears to be legal. However, a challenge to the manner of the arrest and the subsequent treatment may be tenable.

Retaliatory measures

India has reportedly taken the following retaliatory measures: (i) removal of security barricades around the U.S. Embassy in New Delhi, (ii) withdrawal of airport passes and import privileges (iii) identity cards issued to U.S. diplomats to be turned in and (iv) refusal by several leaders including the Speaker of the Lok Sabha and the National Security Adviser to meet a visiting U.S. Congressional delegation. Some politicians have also suggested prosecution of same-sex partners of U.S. diplomats.

India has reportedly taken the following retaliatory measures: (i) removal of security barricades around the U.S. Embassy in New Delhi, (ii) withdrawal of airport passes and import privileges (iii) identity cards issued to U.S. diplomats to be turned in and (iv) refusal by several leaders including the Speaker of the Lok Sabha and the National Security Adviser to meet a visiting U.S. Congressional delegation. Some politicians have also suggested prosecution of same-sex partners of U.S. diplomats.

While some of these measures such as refusal to meet the delegation or withdrawing discretionary privileges are merely political in nature and are best left to the discretion of such politicians, other steps like reducing security measures at diplomatic premises and embassies may violate international law, specifically Article 22(2) of the 1961 Convention that imposes a special duty upon the host State (i.e., India) to take all appropriate steps to protect the premises of the mission against intrusion or damage, or disturbance of peace or impairment of its dignity.

Even presuming that the U.S. government is in breach of its international law obligations, it does not warrant retaliation by India, by means which breach international law. International law allows countermeasures (breach of international obligations in response to a breach by the targeted country) only as a last resort and in very narrowly defined circumstances. The only options available, that are viable in international law, are a withdrawal of discretionary privileges, declaration of certain members of the U.S. diplomatic and consular staff as persona non grata (which may be considered too drastic a step) or recalling of Indian consular staff and diplomatic agents posted in the U.S.

In terms of international dispute settlement, India has few, if any, legal options. Recourse to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the only possible option, is not available in this case (unless the U.S. consents to the same), since the U.S. has not accepted the compulsory jurisdiction of the ICJ.

While the two countries attempt to iron out their differences through diplomatic and legal channels, Ms. Khobragade can, if she and the government of India so desire, avoid further encounters with the U.S. authorities by remaining in the Indian Embassy or the premises of the Permanent Mission of India to the U.N., which cannot be entered by U.S. authorities without authorisation from India.

Obligations of India and Indians

Notwithstanding the several privileges and immunities Indian diplomats and consular officers are entitled to, they have a corresponding duty under the 1961 Convention and the 1963 Convention, to respect the laws and regulations of the host State. Irrespective of how Ms. Khobragade was treated by U.S. authorities, we must not forget the original allegation that she is in violation of U.S. law.

Notwithstanding the several privileges and immunities Indian diplomats and consular officers are entitled to, they have a corresponding duty under the 1961 Convention and the 1963 Convention, to respect the laws and regulations of the host State. Irrespective of how Ms. Khobragade was treated by U.S. authorities, we must not forget the original allegation that she is in violation of U.S. law.

This possible violation of host State law needs to be investigated by Indian authorities. It is imperative that India develop a framework to address misconduct of Indian officials abroad, who have been exempted from prosecution due to consular or diplomatic immunity. Though not an obligation under international law, such a step by India will go a long way as a goodwill diplomatic gesture. It will also ensure quick responses from other countries when pleading immunity on behalf of a national, since there would be an assurance that the offender would face legal consequences in one or other jurisdiction.

Also, India’s latest step of re-designating Ms. Khobragade as a diplomatic agent to the U.N., with a view to bring her under diplomatic immunity, may be viewed internationally as an abuse of the international legal process, given that Section 14 of the 1946 Convention on the Privileges and Immunities of the United Nations (which governs immunities of representatives of the Members to the U.N., since the 1961 Convention is silent on it) expressly states: “Privileges and immunities are accorded to the representatives of Members not for the personal benefit of the individuals themselves, but in order to safeguard the independent exercise of their functions in connection with the United Nations. Consequently, a Member not only has the right but is under a duty to waive the immunity of its representative in any case where the immunity would impede the course of justice, and it can be waived without prejudice to the purpose for which the immunity is accorded.”

(Deepak Raju recently graduated with an LLM in international law from the University of Cambridge. E-mail: deepakelanthoor@gmail.com; Rukmini Das is a research fellow at Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, New Delhi. E-mail:rukmini.das@vidhilegalpolicy.in)

Sunday, 24 June 2012

‘Terrorism Isn’t The Disease; Egregious Injustice Is’

NARENDRA BISHT

INTERVIEW

‘Terrorism Isn’t The Disease; Egregious Injustice Is’

On laws like AFSPA, Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, sedition, democracy, terrorism and more

|

No one individual critic has taken on the Indian State like Arundhati Roy has. In a fight that began with Pokhran, moved to Narmada, and over the years extended to other insurgencies, people’s struggles and the Maoist underground, she has used her pensmanship to challenge India’s government, its elite, corporate giants, and most recently, the entire structure of global finance and capitalism. She was jailed for a day in 2002 for contempt of court, and slapped with sedition charges in November 2010 for an alleged anti-India speech she delivered, along with others, at a seminar in New Delhi on Kashmir, titled ‘Azadi—the only way’. Excerpts from an interview to Panini Anand:

How do you look at laws like sedition and the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, or those like AFSPA, in what is touted as the largest democracy?

I’m glad you used the word touted. It’s a good word to use in connection with India’s democracy. It certainly is a democracy for the middle class. In places like Kashmir or Manipur or Chhattisgarh, democracy is not available. Not even in the black market. Laws like the UAPA, which is just the UPA government’s version of POTA, and the AFSPA are ridiculously authoritarian—they allow the State to detain and even kill people with complete impunity. They simply ought to have no place in a democracy. But as long as they don’t affect the mainstream middle class, as long as they are used against people in Manipur, Nagaland or Kashmir, or against the poor or against Muslim ‘terrorists’ in the ‘mainland’, nobody seems to mind very much.

Are the people waging war against the State or is the State waging war against its people? How do you look at the Emergency of the ’70s, or the minorities who feel targeted, earlier the Sikhs and now the Muslims?

Some people are waging war against the State. The State is waging a war against a majority of its citizens. The Emergency in the ’70s became a problem because Indira Gandhi’s government was foolish enough to target the middle class, foolish enough to lump them with the lower classes and the disenfranchised. Vast parts of the country today are in a much more severe Emergency-like situation. But this contemporary Emergency has gone into the workshop for denting-painting. It’s come out smarter, more streamlined. I’ve said this before: look at the wars the Indian government has waged since India became a sovereign nation; look at the instances when the army has been called out against its ‘own’ people—Nagaland, Assam, Mizoram, Manipur, Kashmir, Telangana, Goa, Bengal, Punjab and (soon to come) Chhattisgarh—it is a State that is constantly at war. And always against minorities—tribal people, Christians, Muslims, Sikhs, never against the middle class, upper-caste Hindus.

How does one curb the cycle of violence if the State takes no action against ultra-left ‘terrorist groups’? Wouldn’t it jeopardise internal security?

I don’t think anybody is advocating that no action should be taken against terrorist groups, not even the ‘terrorists’ themselves. They are not asking for anti-terror laws to be done away with. They are doing what they do, knowing full well what the consequences will be, legally or otherwise. They are expressing fury and fighting for a change in a system that manufactures injustice and inequality. They don’t see themselves as ‘terrorists’. When you say ‘terrorists’ if you are referring to the CPI (Maoist), though I do not subscribe to Maoist ideology, I certainly do not see them as terrorists. Yes they are militant, they are outlaws. But then anybody who resists the corporate-state juggernaut is now labelled a Maoist—whether or not they belong to or even agree with the Maoist ideology. People like Seema Azad are being sentenced to life imprisonment for possessing banned literature. So what is the definition of ‘terrorist’ now, in 2012? It is actually the economic policies that are causing this massive inequality, this hunger, this displacement that is jeopardising internal security—not the people who are protesting against them. Do we want to address the symptoms or the disease? The disease is not terrorism. It’s egregious injustice. Sure, even if we were a reasonably just society, Maoists would still exist. So would other extremist groups who believe in armed resistance or in terrorist attacks. But they would not have the support they have today. As a country, we should be ashamed of ourselves for tolerating this squalor, this misery and the overt as well as covert ethnic and religious bigotry we see all around us. (Narendra Modi for Prime Minister!! Who in their right mind can even imagine that?) We have stopped even pretending that we have a sense of justice. All we’re doing is genuflecting to major corporations and to that sinking ocean-liner known as the United States of America.

Is the State acting like the Orwellian Big Brother, with its tapping of phones, attacks on social networks?

The government has become so brazen about admitting that it is spying on all of us all the time. If it does not see any protest on the horizon, why shouldn’t it? Controlling people is in the nature of all ruling establishments, is it not? While the whole country becomes more and more religious and obscurantist, visiting shrines and temples and masjids and churches in their millions, praying to one god or another to be delivered from their unhappy lives, we are entering the age of robots, where computer-programmed machines will decide everything, will control us entirely—they’ll decide what is ethical and what is not, what collateral damage is acceptable and what is not. Forget religious texts. Computers will decide what’s right and wrong. There are surveillance devices the size of a sandfly that can record our every move. Not in India yet, but coming soon, I’m sure. The UID is another elaborate form of control and surveillance, but people are falling over themselves to get one. The challenge is how to function, how to continue to resist despite this level of mind-games and surveillance.

How do you look at laws like sedition and the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, or those like AFSPA, in what is touted as the largest democracy?

I’m glad you used the word touted. It’s a good word to use in connection with India’s democracy. It certainly is a democracy for the middle class. In places like Kashmir or Manipur or Chhattisgarh, democracy is not available. Not even in the black market. Laws like the UAPA, which is just the UPA government’s version of POTA, and the AFSPA are ridiculously authoritarian—they allow the State to detain and even kill people with complete impunity. They simply ought to have no place in a democracy. But as long as they don’t affect the mainstream middle class, as long as they are used against people in Manipur, Nagaland or Kashmir, or against the poor or against Muslim ‘terrorists’ in the ‘mainland’, nobody seems to mind very much.

|

Some people are waging war against the State. The State is waging a war against a majority of its citizens. The Emergency in the ’70s became a problem because Indira Gandhi’s government was foolish enough to target the middle class, foolish enough to lump them with the lower classes and the disenfranchised. Vast parts of the country today are in a much more severe Emergency-like situation. But this contemporary Emergency has gone into the workshop for denting-painting. It’s come out smarter, more streamlined. I’ve said this before: look at the wars the Indian government has waged since India became a sovereign nation; look at the instances when the army has been called out against its ‘own’ people—Nagaland, Assam, Mizoram, Manipur, Kashmir, Telangana, Goa, Bengal, Punjab and (soon to come) Chhattisgarh—it is a State that is constantly at war. And always against minorities—tribal people, Christians, Muslims, Sikhs, never against the middle class, upper-caste Hindus.

How does one curb the cycle of violence if the State takes no action against ultra-left ‘terrorist groups’? Wouldn’t it jeopardise internal security?

I don’t think anybody is advocating that no action should be taken against terrorist groups, not even the ‘terrorists’ themselves. They are not asking for anti-terror laws to be done away with. They are doing what they do, knowing full well what the consequences will be, legally or otherwise. They are expressing fury and fighting for a change in a system that manufactures injustice and inequality. They don’t see themselves as ‘terrorists’. When you say ‘terrorists’ if you are referring to the CPI (Maoist), though I do not subscribe to Maoist ideology, I certainly do not see them as terrorists. Yes they are militant, they are outlaws. But then anybody who resists the corporate-state juggernaut is now labelled a Maoist—whether or not they belong to or even agree with the Maoist ideology. People like Seema Azad are being sentenced to life imprisonment for possessing banned literature. So what is the definition of ‘terrorist’ now, in 2012? It is actually the economic policies that are causing this massive inequality, this hunger, this displacement that is jeopardising internal security—not the people who are protesting against them. Do we want to address the symptoms or the disease? The disease is not terrorism. It’s egregious injustice. Sure, even if we were a reasonably just society, Maoists would still exist. So would other extremist groups who believe in armed resistance or in terrorist attacks. But they would not have the support they have today. As a country, we should be ashamed of ourselves for tolerating this squalor, this misery and the overt as well as covert ethnic and religious bigotry we see all around us. (Narendra Modi for Prime Minister!! Who in their right mind can even imagine that?) We have stopped even pretending that we have a sense of justice. All we’re doing is genuflecting to major corporations and to that sinking ocean-liner known as the United States of America.

Is the State acting like the Orwellian Big Brother, with its tapping of phones, attacks on social networks?

The government has become so brazen about admitting that it is spying on all of us all the time. If it does not see any protest on the horizon, why shouldn’t it? Controlling people is in the nature of all ruling establishments, is it not? While the whole country becomes more and more religious and obscurantist, visiting shrines and temples and masjids and churches in their millions, praying to one god or another to be delivered from their unhappy lives, we are entering the age of robots, where computer-programmed machines will decide everything, will control us entirely—they’ll decide what is ethical and what is not, what collateral damage is acceptable and what is not. Forget religious texts. Computers will decide what’s right and wrong. There are surveillance devices the size of a sandfly that can record our every move. Not in India yet, but coming soon, I’m sure. The UID is another elaborate form of control and surveillance, but people are falling over themselves to get one. The challenge is how to function, how to continue to resist despite this level of mind-games and surveillance.

|

Why do you feel there’s no mass reaction in the polity to the plight of undertrials in jails, people booked under sedition or towards encounter killings? Are these a non-issue manufactured by few rights groups?

Of course, they are not non-issues. This is a huge issue. Thousands of people are in jail, charged with sedition or under the UAPA, broadly they are either accused of being Maoists or Muslim ‘terrorists’. Shockingly, there are no official figures. All we have to go on is a sense you get from visiting places, from individual rights activists collating information in their separate areas. Torture has become completely acceptable to the government and police establishment. The nhrc came up with a report that mentioned 3,000 custodial deaths last year alone. You ask why there is no mass reaction? Well, because everybody who reacts is jailed! Or threatened or terrorised. Also, between the coopting and divisiveness of ngos and the reality of State repression and surveillance, I don’t know whether mass movements have a future. Yes, we keep looking to the Arab ‘spring’, but look a little harder and you see how even there, people are being manipulated and ‘played’. I think subversion will take precedence over mass resistance in the years to come. And unfortunately, terrorism is an extreme form of subversion.

Without the State invoking laws, an active police, intelligence, even armed forces, won’t we have anarchy?

We will end up in a state of—not anarchy, but war—if we do not address the causes of people’s rising fury. When you make laws that serve the rich, that helps them hold onto their wealth, to amass more and more, then dissent and unlawful activity becomes honourable, does it not? Eventually I’m not at all sure that you can continue to impoverish millions of people, steal their land, their livelihoods, push them into cities, then demolish the slums they live in and push them out again and expect that you can simply stub out their anger with the help of the army and the police and prison terms. But perhaps I’m wrong. Maybe you can. Starve them, jail them, kill them. And call it Globalisation with a Human Face.

Of course, they are not non-issues. This is a huge issue. Thousands of people are in jail, charged with sedition or under the UAPA, broadly they are either accused of being Maoists or Muslim ‘terrorists’. Shockingly, there are no official figures. All we have to go on is a sense you get from visiting places, from individual rights activists collating information in their separate areas. Torture has become completely acceptable to the government and police establishment. The nhrc came up with a report that mentioned 3,000 custodial deaths last year alone. You ask why there is no mass reaction? Well, because everybody who reacts is jailed! Or threatened or terrorised. Also, between the coopting and divisiveness of ngos and the reality of State repression and surveillance, I don’t know whether mass movements have a future. Yes, we keep looking to the Arab ‘spring’, but look a little harder and you see how even there, people are being manipulated and ‘played’. I think subversion will take precedence over mass resistance in the years to come. And unfortunately, terrorism is an extreme form of subversion.

Without the State invoking laws, an active police, intelligence, even armed forces, won’t we have anarchy?

We will end up in a state of—not anarchy, but war—if we do not address the causes of people’s rising fury. When you make laws that serve the rich, that helps them hold onto their wealth, to amass more and more, then dissent and unlawful activity becomes honourable, does it not? Eventually I’m not at all sure that you can continue to impoverish millions of people, steal their land, their livelihoods, push them into cities, then demolish the slums they live in and push them out again and expect that you can simply stub out their anger with the help of the army and the police and prison terms. But perhaps I’m wrong. Maybe you can. Starve them, jail them, kill them. And call it Globalisation with a Human Face.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)