Salil Tripathi in The Guardian

Some thought the BJP’s reduced majority after recent elections would humble it. Tell that to the Booker prize-winning author

This month, the highest ranking bureaucrat of the state of Delhi, Vinai Kumar Saxena, gave his permission for the Delhi police to prosecute Arundhati Roy and Sheikh Showkat Hussain for remarks they made at a public event 14 years ago. The opposition Aam Aadmi party governs Delhi, but the capital’s police reports to the central government’s home ministry. While the prime minister, Narendra Modi, lost his parliamentary majority in the recently concluded elections, the prosecution of Roy shows that those who expected a chastened government willing to operate differently are likely to be disappointed.

Hussain and Roy are to be tried for making speeches at a conference called Azadi [Urdu for “freedom”]: The Only Way, which questioned Indian rule in the then state of Jammu and Kashmir. Hussain is a Kashmiri academic, author and human rights activist. Roy is among India’s most celebrated authors, with a wide following around the world.

After Roy won the Booker prize in 1997, for The God of Small Things, she became the nation’s darling. It was the year of India, in a sense: the 50th anniversary of India’s independence, and the year Salman Rushdie, the first Indian-born winner of the Booker, published a volume anthologising new Indian literature. Roy was a fresh voice from the still young, post-independence India, reminding us of the multitude of stories from the subcontinent not yet told. She became an idol to be followed and imitated. Indeed, in Mira Nair’s 2001 film Monsoon Wedding, a character who wants to pursue creative writing at an American university is told by an uncle: “Lots of money in writing these days. That girl who won the Booker prize became an overnight millionaire.”

But many of those uncles – powerful and privileged – are no longer happy with Roy. When Saxena announced that Roy could be prosecuted under India’s draconian Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), because she had said at this event that Kashmir had never been an “integral” part of India, there was outrage abroad from intellectuals and writers’ organisations, but responses in India were less spirited. While politicians such as Mahua Moitra of the Trinamool Congress were prompt in criticising the move, others on social media commended the government and gleefully admonished those who defended Roy. Their reasoning: Roy was “anti-national”, unpatriotic, sympathising with terrorists, and needed to face the full force of the law.

The UAPA is a draconian law – being granted bail is extremely difficult, and the accused can be taken into custody before the trial even begins. And the proceedings may not begin for years, as has happened to several leading dissidents during the Modi years. But its use against Roy in this case is puzzling. Lawyers have pointed out procedural gaps: it is not known if the Delhi police has filed a formal report, known as “charge sheet”, after conducting investigations, which is necessary before prosecution can begin. India’s highest court requires the authorities to explain why they wish to use the UAPA, and Saxena’s order offers no explanation. Nor does a 14 June note published on social media that carries his signature. Under UAPA, central government approval is necessary before prosecution can begin, and the authority can grant such permission only after there has been an independent review of evidence gathered. It is not known publicly if any of those steps have been taken, raising profound questions about the legality of the approval itself. Some lawyers believe that the government may have invoked the UAPA to sidestep the legal bar of the statute of limitations.

Despite this travesty, if Roy is not getting an outpouring of public sympathy, it has to do with how India has changed in the past quarter of a century. Its elite are keen to shed the past image of a poor, struggling country. India deserves a seat at the main table, they say; and dissidents and writers who question Indian policies are inconvenient do-gooders whose pessimism interferes with India’s ascent. On significant issues on which much of India’s majoritarian, powerful elite believes there is consensus, Roy is the naysayer.

Consider Roy’s views on Kashmir, the disputed territory over which India and Pakistan have gone to at least three wars, and where Pakistan-supported insurgents have sought independence. The Indian army has stationed tens of thousands of troops there, and human rights groups have accused the Indian state and extremist groups of abuses. Roy has listened to Kashmiri voices and challenged India’s human rights record for more than a decade. She has persistently opposed India’s governing consensus and conduct in Kashmir – her last novel, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness – describes the Kashmir crisis graphically. Triumphalist Indians don’t like to hear such criticism.

Nor do many Indians like her questioning the wisdom of building large dams to produce electricity or irrigate farms. Building dams was the dream of India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru; he called dams “temples of modern India”. The dams helped farms and generated power, and well-meaning development experts questioned Roy’s stance. But Roy showed how they also displaced hundreds of thousands of people. The dispossessed saw the mandatory land acquisitions as a land grab by the powerful.

Roy has also written critically of Gandhi’s views on the “untouchable” caste Dalits, calling them discriminatory and patronising, and has been a vocal critic of India’s nuclear tests and arsenal. These views offend India’s conservative and liberal opinion. India’s peaceniks admire Gandhi; India’s Hindu nationalists hate Gandhi but love the bomb. The fact that she wins accolades abroad, and prominent western publications give her space to write, rattles and rankles them even more. The powerful in India want to hear only praise; Roy keeps reminding the world of the rot within.

Whether or not Roy gets prosecuted remains to be seen; prosecuting authorities may feel the evidence isn’t enough, or much time has passed, and her lawyers may succeed with their procedural objections. The government too may prefer the ambiguity, hoping that the threat of prosecution might keep her, and other dissidents, silent.

But one thing is certain: it was wrong to assume that Modi has changed. Pursuing someone as high-profile as Roy is the government’s way of warning critics that they must not expect anything different. The sword hangs over the critics; Roy reminds us why the pen must remain mightier than the sword.

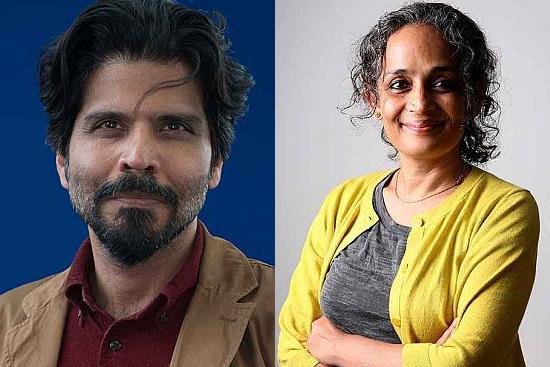

Pankaj Mishra and Arundhati Roy have both spoken by now about the election results in India and if you are a Modi voter, you are likely not too happy with their views. I would like to suggest that if you are not a Modi voter, you should also be a bit unhappy at how much attention these particular writers get as “the voice of the Left/Liberal/Secular side of India”. I really think that far too many highly educated South Asian people read Pankaj Mishra, Arundhati Roy and their ilk.

Obviously, I also believe far too many people in the Western elite read them, but at least their admiration is more understandable. They need native informants who can reinforce their preconceived notions and if these native informants helpfully repeat the Western Left’s own pet theories back to them, so much the better. That is not my main concern today.

I am concerned that too many good, intelligent Desi people who want to make a positive contribution to their societies and whose elite status puts them in a position to do so are lost to useful causes because they have been enthralled by fashionable writers like Pankaj Mishra, Arundhati Roy and Tariq Ali (heretofore shortened to Pankajism, with any internal disagreements between various factions of the People’s Front of Judea being ignored).

The opportunity cost of this mish-mash of Marxism-Leninism, postmodernism, “postcolonial theory”, environmentalism and emotional massage (not necessarily in that order) is not trivial for liberals and leftists in the Indian subcontinent. It's worth noting that there is no significant market for Pankajism in China or Korea for advice about their own societies, though they may use it as an anti-imperialist propaganda tool should the need arise; a fact that may have a tiny bearing on some of the difference between China and India.

I believe the damage extends beyond self-identified liberals and leftists; variants of Pankajism are so widely circulated within the English speaking elites of the world that they seep into our arguments and discussions without any explicit acknowledgement or awareness of their presence.

What I present below is not a systematic theses (though it is, among other things, an appeal to someone more academically inclined to write exactly such a thesis) but a conversation starter:

1. There are some people who have what they regard as a Marxist-Leninist worldview. This post is NOT about them. Whether they are right or wrong (and I now think the notion of a violent “people’s revolution” is wrong in some very fundamental ways), there is a certain internal logic to their choices.

They do not expect electoral politics and social democratic reformist parties to deliver the change they desire, though they may participate in such politics and support such parties as a tactical matter (for that matter they may also support right wing parties if the revolutionary situation so demands).

They are also very clear about the role of propaganda in revolutionary politics and therefore may consciously take positions that appear simplistic or even silly to pedantic observers, in the interest of the greater revolutionary cause.

Their choices, their methods and their aims are all open to criticism, but they make some sort of internally consistent sense within their own worldview. In so far as their worldview fails to fit the facts of the world, they have to invent epicycles and equants to fit facts to theory, but that is not the topic today. IF you are a believer in “old fashioned Marxist-Leninist revolution” and regard “bourgeois politics” as a fraud, then this post is not about you.

2. But most of the left-leaning or liberal members of the South Asian educated elite (and a significant percentage of the educated elite in India and Pakistan are left leaning and/or liberal, at least in theory; just look around you) are not self-identified revolutionary socialists.

I deliberately picked on Pankaj Mishra and Arundhati Roy because both seem to fall in this category (if they are committed “hardcore Marxists” then they have done a very good job of obfuscating this fact).

Tariq Ali may appear to be a different case (he seems to have been consciously Marxist-Leninist and “revolutionary” at some point), but for all practical purposes, he has joined the Pankajists by now; relying on mindless repetition of slogans and formulas and recycled scraps of conversation to manage his brand.

If you consider him a Marxist-Leninist (or if he does so himself), you may mentally delete him from this argument.

3. The Pankajists are not revolutionaries, though they like revolutionaries and occasionally fantasize about walking with the comrades (but somehow always make sure to get back to their pads in London or Delhi for dinner).

They are not avowedly Marxist, though they admire Marx; they strongly disapprove of capitalists and corporations, but they have never said they would like to hang the last capitalist with the entrails of the last priest.

So are they then social democrats? Perish the thought. They would not be caught dead in a reformist social democratic party.

4. They hate how Westernization is destroying traditional cultures, but every single position they have ever held was first advocated by someone in the West (and 99% were never formulated in this form by anyone in the traditional cultures they apparently prefer to “Westernization”).

In fact most of their “social positions” (gay rights, feminism, etc) were anathema to the “traditional cultures” they want to protect and utterly transform at the same time. They are totally Eurocentric (in that their discourse and its obsessions are borrowed whole from completely Western sources), but simultaneously fetishize the need to be “anti-European” and “authentic”.

Here it is important to note that most of their most cherished prejudices actually arose in the context of the great 20th century Marxist-Leninist revolutionary struggle. e.g. the valorization of revolution and of “people’s war”, the suspicion of reformist parties and bourgeois democracy, the yearning for utopia, and the feeling that only root and branch overthrow of capitalism will deliver it. These are all positions that arose (in some reasonably sane sequence) from hardcore Marxist-Leninist parties and their revolutionary program (good or not is a separate issue), but that continue to rattle around unexamined in the heads of the Pankajists.

The Pankajists also find the “Hindu Right” and its fascist claptrap and its admiration of “strength” and machismo alarming, but Pankaj (for example) admires Jamaluddin Afghani and his fantasies of Muslim power and its conquering warriors so much, he promoted him as one of the great thinkers of Asia in his last book. This too is a recurring pattern. Strong men and their cults are awful and alarming, but also become heroic and admirable when an “anti-Western” gloss can be put on them, especially if they are not Hindus. i.e. For Hindus, the approved anti-Western heroes must not be Rightists, but this second requirement is dropped for other peoples.

They are proudly progressive, but they also cringe at the notion of “progress”. They are among the world’s biggest users of modern technology, but also among its most vocal (and scientifically clueless) critics. Picking up that the global environment is under threat (a very modern scientific notion if there ever was one), they have also added some ritualistic sound bites about modernity and its destruction of our beloved planet (with poor people as the heroes who are bravely standing up for the planet). All of this is partly true (everything they say is partly true, that is part of the problem) but as usual their condemnations are data free and falsification-proof. They are also incapable of suggesting any solution other than slogans and hot air.

Finally, Pankajists purportedly abhor generalization, stereotyping and demagoguery, but when it comes to people on the Right (and by their definition, anyone who tolerates capitalism or thinks it may work in any setting is “Right wing”) all these dislikes fly out of the window. They generalize, stereotype, distort and demonize with a vengeance.

You get the picture...there are emotionally satisfying and fashionable sound bites that sound like they are saying something profound, until you pay closer attention and most of the meaning seems to evaporate.

My contention is that what remains after that evaporation is pretty much what any reasonable “bourgeois” reformist social democrat would say.

Pankaj and Roy add no value at all to that discourse. And they take away far too much with sloganeering, snide remarks, exaggeration and hot air.

5. This confused mish-mash is then read by “us people” as “analysis”. Instead of getting new insights into what is going on and what is to be done, we come out by the same door as in we went; we come out with our opinions seemingly validated by someone who uses a lot of big words and sprinkles his “analysis” with quotes from serious books.

We then discuss this “analysis” with friends who also read Pankaj and Arundhati in their spare time. Everyone is happy, but I am going to make the not-so-bold claim that you would learn more by reading The Economist, and you would be harmed less by it.

6. Pankajism as cocktail party chatter is not a big deal. After all, we have a human need to interact with other humans and talk about our world, and if this is the discourse of our subculture, so be it. But then the gobbledygook makes its way beyond those who only need it for idle entertainment. Real journalists, activists and political workers read it and it helps, in some small way, to further fog up the glasses of all of them. The parts that are useful are exactly the parts you could pick up from any of a number of well informed and less hysterical observers (if you don’t like theEconomist, try Mark Tully). What Pankajism adds is exactly what we do not need: lazy dismissal of serious solutions, analysis uncontaminated by any scientific and objective data, and snide dismissal of bourgeois politics.

7. If and when (and the “when” is rather frequent) reality A fails to correspond with theory A, Pankajists, like Marxists, also have to come up with newer and more complicated epicycles to save the appearances; and we then have to waste endless time learning the latest epicycles and arguing about them.

All of this while people in India (and to a lesser and more imperfect extent, even in Pakistan) already have a reasonably good constitution and, incompetent and corrupt, but improvable institutions. There are large political parties that attract mass support and participation. There are academics and researchers, analysts and thinkers, creative artists and brilliant inventors, and yes, even sincere conservatives and well-meaning right-wingers.

I think it may be possible to make things better, even if it is not possible to make them perfect. “People’s Revolution” (which did not turn out well in any country since it was valorized in 1917 as the way to cut the Gordian knot of society and transform night into day in one heroic bound) is not the only choice or even the most reasonable choice.

Strengthening the imperfect middle is a procedure that is vastly superior to both Left and Right wing fantasies of utopian transformation. The system that exists is probably not irreparably broken and can still avoid falling into fascist dictatorship or complete anarchy, but my point is that even if they system is unfixable and South Asia is due for huge, violent revolution, these people are not the best guide to it.

Look, for example at the extremely long article produced by Pankaj on the Indian elections. This is the opening paragraph:

In A Suitable Boy, Vikram Seth writes with affection of a placid India's first general election in 1951, and the egalitarian spirit it momentarily bestowed on an electorate deeply riven by class and caste: "the great washed and unwashed public, sceptical and gullible", but all "endowed with universal adult suffrage.Well, was that good? Or bad? Or neither? Were things better then, than they are now? There is also a hint that universal adult suffrage was a bit of a fraud even then. That seems to be the implication, but in typical Pankaj style, this is never really said outright (that may bring up uncomfortable questions of fact). I doubt if any two readers can come up with the same explanation of what he means; which is usually a good sign that nothing has been said.

There follows a description of why Modi and the RSS are such a threat to India. This is a topic on which many sensible things can be said and he says many of them, but even here (where he is on firmer ground, in that there are really disturbing questions to be asked and answered) the urge to go with propaganda and sound bites is very strong. And the secret of Modi’s success remains unclear.

We learn that development has been a disaster, but that people seem to want more of it. If it has been so bad, why do they want more of it? Because they lack agency and are gullible fools led by the capitalist media? If people do not know what is good for them, and they have to be told the facts by a very small coterie of Western educated elite intellectuals, then what does this tell us about “the people”? And about Western education?

Supporters will say Pankaj has raised questions about Indian democracy and especially about Modi and the right-wing BJP that need to be asked. And indeed, he has. But here is my point: the good parts of his article are straightforward liberal democratic values. Mass murder and state-sponsored pogroms are wrong in the eyes of any mainstream liberal order. If an elected official connived in, or encouraged, mass murder, then this is wrong in the eyes of the law and in the context of routine bourgeois politics. That politics does provide mechanisms to counter such things, though the mechanisms do not always work (what does?).

But these liberal democratic values are the very values Pankaj holds in not-so-secret contempt and undermines with every snide remark. It may well be that “a western ideal of liberal democracy and capitalism” Is not going to survive in India. But the problem is that Pankaj is not even sure he likes that ideal in the first place. In fact, he frequently writes as if he does not. But he is always sufficiently vague to maintain deniability. There is always an escape hatch. He never said it cannot work. But he never really said it can either...

To say “I want a more people friendly democracy” is to say very little. What exactly is it that needs to change and how in order to fix this model? These are big questions. They are being argued over and fought out in debates all over the world. I am not belittling the questions or the very real debate about them. But I am saying that Pankajism has little or nothing to contribute to this debate.

Read him critically and it soon becomes clear that he doesn’t even know the questions very well, much less the answers... But he always sounds like he is saying something deep. And by doing so, he and his ilk have beguiled an entire generation of elite Westernized Indians (and Pakistanis, and others) into undermining and undervaluing the very mechanisms that they actually need to fix and improve. It has been a great disservice.

By the way, the people of India have now disappointed Pankaj so much (because 31% of them voted for the BJP? Is that all it takes to destroy India?) that he went and dug up a quote from Ambedkar about the Indian people being “essentially undemocratic”. I can absolutely guarantee that if someone on the right were to say that Indians are essentially undemocratic, all hell would break loose in Mishraland.

See this paragraph:

In many ways, Modi and his rabble – tycoons, neo-Hindu techies, and outright fanatics— are perfect mascots for the changes that have transformed India since the early 1990s: the liberalisation of the country's economy, and the destruction by Modi's compatriots of the 16th-century Babri mosque in Ayodhya. Long before the killings in Gujarat, Indian security forces enjoyed what amounted to a licence to kill, torture and rape in the border regions of Kashmir and the north-east; a similar infrastructure of repression was installed in central India after forest-dwelling tribal peoples revolted against the nexus of mining corporations and the state. The government's plan to spy on internet and phone connections makes the NSA's surveillance look highly responsible. Muslims have been imprisoned for years without trial on the flimsiest suspicion of "terrorism"; one of them, a Kashmiri, who had only circumstantial evidence against him, was rushed to the gallows last year, denied even the customary last meeting with his kin, in order to satisfy, as the supreme court put it, "the collective conscience of the people".Many of these things have indeed happened (most of them NOT funded by corporations or conducted by the BJP incidentally) but their significance, their context and, most critically, the prognosis for India, are all subtly distorted. Mishra is not wrong, he is not even wrong. To try and take apart this paragraph would take up so much brainpower that it is much better not to read it in the first place. There are other writers (on the Left and on the Right) who are not just repeating fashionable sound bites. Read them and start an argument with them. Pankajism is not worth the time and effort. There is no there there…

PS: I admit that this article has been high on assertions and low on evidence. But I did read Pankaj Mishra’s last (bestselling) book and wrote a sort of rolling review while I was reading it. It is very long and very messy (I never edited it), but it will give you a bit of an idea of where I am coming from. You can check it out at this link: Pankaj Mishra’s tendentious little book