'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label neoliberal. Show all posts

Showing posts with label neoliberal. Show all posts

Tuesday, 21 May 2024

Friday, 18 August 2023

A level Economics: The 1973 coup against democratic socialism in Chile still matters

It happened 50 years ago, changed the course of world history – and revealed just how authoritarian conservatives are. Andy Beckett in The Guardian

Fifty years on, the 1973 coup in Chile still haunts politics there and far beyond. As we approach its anniversary, on 11 September, the violent overthrow of the elected socialist government of Salvador Allende and its replacement by the brutal dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet are already being marked in Britain, through a period of remembrance scheduled to include dozens of separate exhibitions and events. Among these will be a march in Sheffield, archival displays in Edinburgh, a concert in Swansea, and a conference and picket of the Chilean embassy in London.

Few past events in faraway countries receive this level of attention. Military takeovers were not unusual in South America during the cold war. And Chile has been a relatively stable democracy since the Pinochet dictatorship ended, 33 years ago. So why does the 1973 coup still resonate?

In the UK, one answer is that roughly 2,500 Chilean refugees fled here after the coup, despite an unwelcoming Conservative government. “It is intended to keep the number of refugees to a very small number and, if our criteria are not fully met, we may accept none of them,” said a Foreign Office memo not released until three decades afterwards.

The Chileans came regardless, partly because leftwing activists, trade unionists and politicians including Tony Benn and Jeremy Corbyn created a solidarity movement – of a scale and duration harder to imagine in our more politically impatient times – which helped the refugees build new lives, and campaigned with them for years against the Pinochet regime. Some of these exiles settled in Britain permanently; veterans of the solidarity movement are involved in this year’s remembrance events, as they have been in earlier anniversaries. The left’s reverence for old struggles can sometimes distract it or weigh it down, but it is also a source of emotional and cultural strength, and an acknowledgment that the past and present are often more linked than we realise.

Two weeks ago, it was revealed that an old army helicopter that stands in a wood in Sussex as part of a paintball course had previously been used by the Pinochet government, to transport dissidents and then throw them into the sea. The dictatorship was a pioneer of this and other methods of “disappearing” its enemies and perceived enemies, believing that lethal abductions would frighten the population into obedience more effectively than conventional state murders.

Not unconnectedly, the regime also pioneered the harsh free-market policies which transformed much of the world – and which are still supported by most Tories, many rightwing politicians in other countries, and many business interests. In Chile, the idea that a deregulated economy required a highly disciplined citizenry, to avoid the economic semi-anarchy spilling over into society, was exhaustively tested and refined, to the great interest of foreign politicians such as Margaret Thatcher.

Fifty years on, the 1973 coup in Chile still haunts politics there and far beyond. As we approach its anniversary, on 11 September, the violent overthrow of the elected socialist government of Salvador Allende and its replacement by the brutal dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet are already being marked in Britain, through a period of remembrance scheduled to include dozens of separate exhibitions and events. Among these will be a march in Sheffield, archival displays in Edinburgh, a concert in Swansea, and a conference and picket of the Chilean embassy in London.

Few past events in faraway countries receive this level of attention. Military takeovers were not unusual in South America during the cold war. And Chile has been a relatively stable democracy since the Pinochet dictatorship ended, 33 years ago. So why does the 1973 coup still resonate?

In the UK, one answer is that roughly 2,500 Chilean refugees fled here after the coup, despite an unwelcoming Conservative government. “It is intended to keep the number of refugees to a very small number and, if our criteria are not fully met, we may accept none of them,” said a Foreign Office memo not released until three decades afterwards.

The Chileans came regardless, partly because leftwing activists, trade unionists and politicians including Tony Benn and Jeremy Corbyn created a solidarity movement – of a scale and duration harder to imagine in our more politically impatient times – which helped the refugees build new lives, and campaigned with them for years against the Pinochet regime. Some of these exiles settled in Britain permanently; veterans of the solidarity movement are involved in this year’s remembrance events, as they have been in earlier anniversaries. The left’s reverence for old struggles can sometimes distract it or weigh it down, but it is also a source of emotional and cultural strength, and an acknowledgment that the past and present are often more linked than we realise.

Two weeks ago, it was revealed that an old army helicopter that stands in a wood in Sussex as part of a paintball course had previously been used by the Pinochet government, to transport dissidents and then throw them into the sea. The dictatorship was a pioneer of this and other methods of “disappearing” its enemies and perceived enemies, believing that lethal abductions would frighten the population into obedience more effectively than conventional state murders.

Not unconnectedly, the regime also pioneered the harsh free-market policies which transformed much of the world – and which are still supported by most Tories, many rightwing politicians in other countries, and many business interests. In Chile, the idea that a deregulated economy required a highly disciplined citizenry, to avoid the economic semi-anarchy spilling over into society, was exhaustively tested and refined, to the great interest of foreign politicians such as Margaret Thatcher.

Augusto Pinochet, left, and President Salvador Allende attend a ceremony naming Pinochet as commander in chief of the army, 23 August, 1973. Photograph: Enrique Aracena/AP

Another reason that the 1973 coup remains a powerful event is that it left unfinished business at the other end of the political spectrum. The Allende government was an argumentative and ambitious coalition which, almost uniquely, attempted to create a socialist country with plentiful consumer pleasures and modern technology, including a kind of early internet called Project Cybersyn, without Soviet-style repression. For a while, even the Daily Mail was impressed: “An astonishing experiment is taking place,” it reported on the first anniversary of his election. “If it survives, the implications will be immense for other countries.”

The coup happened partly because the government’s popularity, though never overwhelming, rose while it was in office. This rise convinced conservative interests that it would be reelected, and would then take the patchy reforms of its first term much further. For the same reasons, the Allende presidency remains tantalising for some on the left. An updated version of his combination of social liberalism, egalitarianism and mass political participation may still have the potential to transform the left’s prospects, as Corbyn’s successful campaigns in 2015, 2016 and 2017 suggested.

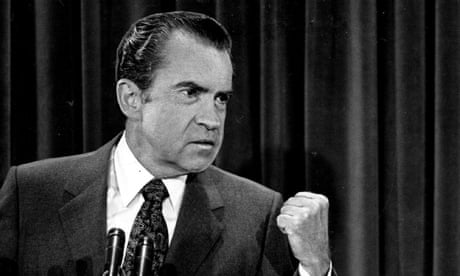

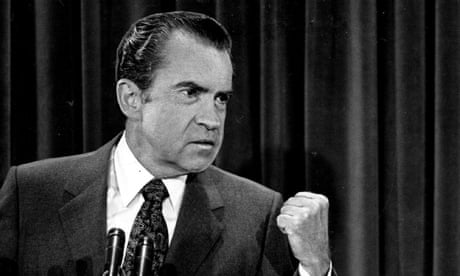

Files reveal Nixon role in plot to block Allende from Chilean presidency

There is one more, bleaker reason to reflect on the coup: for what it revealed about conservatism. When I wrote a book on Chile two decades ago, it was unsettling to learn about how the US Republicans undermined Allende, by covert CIA funding of his enemies, for instance, and how the Conservatives helped Pinochet, through arms sales and diplomatic support. But these moves seemed to be explained largely by cold-war strategies and free-market zealotry, which was fading in the early 21st century.

Yet from today’s perspective, with another Trump presidency threatening, far-right parties in power across Europe, and a Tory government with few, if any, inhibitions about criminalising dissent, the Chile coup looks prophetic. Nowadays the line between conservatism and authoritarianism is not so much blurred occasionally, in national emergencies, as nonexistent in many countries.

Some critics of conservatism would say that it’s naive to think such a line ever existed. In 1930s Europe, for instance, supposedly moderate and pro-democratic rightwing parties often facilitated the rise of fascism. Yet the postwar world, after fascism had been militarily defeated, was meant to be one where such toxic alliances against the left never happened again.

The 1973 coup ended that comfortable assumption. “It is not for us to pass judgment on Chile’s internal affairs,” said the Tory Foreign Office minister Julian Amery in the Commons, two months later, despite the coup having initiated killings and torture on a mass scale. When the coup is remembered, its victims should come first. But the response of conservatives around the world to the crushing of Chile’s democracy and civil liberties should never be forgotten.

Another reason that the 1973 coup remains a powerful event is that it left unfinished business at the other end of the political spectrum. The Allende government was an argumentative and ambitious coalition which, almost uniquely, attempted to create a socialist country with plentiful consumer pleasures and modern technology, including a kind of early internet called Project Cybersyn, without Soviet-style repression. For a while, even the Daily Mail was impressed: “An astonishing experiment is taking place,” it reported on the first anniversary of his election. “If it survives, the implications will be immense for other countries.”

The coup happened partly because the government’s popularity, though never overwhelming, rose while it was in office. This rise convinced conservative interests that it would be reelected, and would then take the patchy reforms of its first term much further. For the same reasons, the Allende presidency remains tantalising for some on the left. An updated version of his combination of social liberalism, egalitarianism and mass political participation may still have the potential to transform the left’s prospects, as Corbyn’s successful campaigns in 2015, 2016 and 2017 suggested.

Files reveal Nixon role in plot to block Allende from Chilean presidency

There is one more, bleaker reason to reflect on the coup: for what it revealed about conservatism. When I wrote a book on Chile two decades ago, it was unsettling to learn about how the US Republicans undermined Allende, by covert CIA funding of his enemies, for instance, and how the Conservatives helped Pinochet, through arms sales and diplomatic support. But these moves seemed to be explained largely by cold-war strategies and free-market zealotry, which was fading in the early 21st century.

Yet from today’s perspective, with another Trump presidency threatening, far-right parties in power across Europe, and a Tory government with few, if any, inhibitions about criminalising dissent, the Chile coup looks prophetic. Nowadays the line between conservatism and authoritarianism is not so much blurred occasionally, in national emergencies, as nonexistent in many countries.

Some critics of conservatism would say that it’s naive to think such a line ever existed. In 1930s Europe, for instance, supposedly moderate and pro-democratic rightwing parties often facilitated the rise of fascism. Yet the postwar world, after fascism had been militarily defeated, was meant to be one where such toxic alliances against the left never happened again.

The 1973 coup ended that comfortable assumption. “It is not for us to pass judgment on Chile’s internal affairs,” said the Tory Foreign Office minister Julian Amery in the Commons, two months later, despite the coup having initiated killings and torture on a mass scale. When the coup is remembered, its victims should come first. But the response of conservatives around the world to the crushing of Chile’s democracy and civil liberties should never be forgotten.

Wednesday, 16 August 2023

Wednesday, 27 July 2022

There is a global debt crisis coming – and it won’t stop at Sri Lanka

Foreign capital flees poorer countries at the first sign of instability. The pandemic and Ukraine war ensure there is plenty of that around writes Jayati Ghosh in The Guardian

This January, even before Sanjana Mudalige’s salary as a sales worker in a shopping mall in Colombo, Sri Lanka, was slashed in half, she had pawned her gold jewellery to try to make ends meet. Ultimately, she quit her job, because the travel costs alone exceeded the pay. Since then, she has shifted from using gas for cooking to chopping firewood, and eats just a quarter of what she did before. Her story, reported in the Washington Post, is one of many in Sri Lanka, where people are watching their children go hungry and their elderly relations suffer for lack of medicines.

The human costs of the crisis only really captured international attention when the massive popular upsurge earlier this month, known as Aragalaya (Sinhalese for “struggle”), led to the peaceful overthrow of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa. His family had ruled Sri Lanka with an iron fist, albeit with electoral legitimacy, for more than 15 years, and is now being blamed by both national and international media for the desperate economic mess the country is in.

But blaming the Rajapaksas alone is too simple. Certainly, the aggressive majoritarianism that they unleashed, along with the alleged corruption and major economic policy disasters of recent years (such as drastic tax cuts and bans on fertiliser imports), were crucial elements of the economic debacle. But this is only part of the story. The deeper and underlying causes of the crisis in Sri Lanka are barely mentioned by most mainstream commentators, perhaps because they reveal uncomfortable truths about the way the global economy works.

This is not a crisis created by a few recent external and internal factors, it has been decades in the making. Ever since its “open economic policy” was adopted in the late 1970s, Sri Lanka has been Asia’s poster boy for neoliberal reform, much like Chile in Latin America. The strategy was the now-familiar one of making exports the basis for economic growth, supported by foreign capital inflows. This led to a significant increase in foreign currency debt, something the IMF and the Davos crowd actively encouraged.

In the period after the 2008 global financial crisis, as low interest rates in advanced economies led to the availability of cheap credit, the Sri Lankan government relied on international sovereign bonds to finance its own spending. Between 2012 and 2020, the debt to GDP ratio doubled to around 80%, with a growing share of this in bonds. The payments due on these debts kept rising in relation to what Sri Lanka could earn from exports and the money sent back home by Sri Lankans working abroad. The disruptions caused by the pandemic and the war in Ukraine made matters much worse, by causing export earnings to fall and sharply increasing the price of essential imports including food and fuel. Foreign exchange reserves plummeted – but the government had to keep paying interest even when it could not import essential fuel.

Looked at in this light, it is clear that Sri Lanka is not alone; if anything, it’s just a harbinger of a coming storm of debt distress in what economists call the “emerging markets”. The past period of incredibly low interest rates in the advanced economies meant that more funds flowed to “emerging” and “frontier” markets from the richer world. While this found cheerleaders in the international financial institutions (IFIs), it was always a problematic process. This is because, unlike in places such as the EU and US, capital leaves low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) at the first sign of any problem.

And these countries were much more battered economically by the pandemic. Advanced economies were able to provide massive countercyclical measures – think of the UK’s furlough programme – because financial markets effectively allowed and even encouraged them to do so. By contrast, LMICs were prevented from increasing fiscal spending by much – because of those same financial markets, which threatened the possibility of credit downgrades and capital flight as government deficits grew larger. Plus they faced significant declines in export and tourism revenues and tighter balance of payments constraints. As a result, their economic recovery has been much more muted and economic conditions remain mostly dire.

The half-hearted attempts at debt relief, such as the moratorium on debt servicing in the first part of the pandemic, only postponed the problem. There has been no meaningful debt restructuring at all. The IMF bewails the situation and does almost nothing, and both it and World Bank add to the problem through their own rigid insistence on repayments and the appalling system of surcharges imposed by the IMF. The G7 and “international community” have been missing in action, which is deeply irresponsible given the scale of the problem and their role in creating it.

The sad truth is that “investor sentiment” moves against poorer economies regardless of the real economic conditions in specific countries. Private credit rating agencies amplify the problem. This means that contagion is all too likely, and it will affect not just economies that are already experiencing difficulties, but a much wider range of LMICs that will face real difficulties in servicing their debts. Lebanon, Suriname and Zambia are already in formal default; Belarus is on the brink; and Egypt, Ghana and Tunisia are in severe debt distress.

Many countries with lower per-capita income and significant absolute poverty are facing stagflation. Billions of people are increasingly unable to afford a basic nutritious diet, and cannot meet basic health expenses. Material insecurity and social tensions are inevitable.

The situation can still be resolved, but it requires urgent action, especially on the part of the IFIs and G7. Speedy and systematic debt resolution actions to bring in private creditors and other creditors, such as China, are needed, as is IFIs doing their own bit to provide debt relief and ending punitive measures such as surcharges. In addition, policies to limit speculation in commodity markets and profiteering by big food and fuel companies must be put in place. Finally, the recycling of special drawing rights (SDRs) – essentially “IMF coupons” – by countries that will not use them to countries that desperately need them is vital, as is another release of SDRs equating to about $650bn to provide immediate relief.

Without these minimal measures, the post-Covid, post-Ukraine global economy is likely to be engulfed in a dystopia of debt defaults, increasing poverty and sociopolitical instability.

This January, even before Sanjana Mudalige’s salary as a sales worker in a shopping mall in Colombo, Sri Lanka, was slashed in half, she had pawned her gold jewellery to try to make ends meet. Ultimately, she quit her job, because the travel costs alone exceeded the pay. Since then, she has shifted from using gas for cooking to chopping firewood, and eats just a quarter of what she did before. Her story, reported in the Washington Post, is one of many in Sri Lanka, where people are watching their children go hungry and their elderly relations suffer for lack of medicines.

The human costs of the crisis only really captured international attention when the massive popular upsurge earlier this month, known as Aragalaya (Sinhalese for “struggle”), led to the peaceful overthrow of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa. His family had ruled Sri Lanka with an iron fist, albeit with electoral legitimacy, for more than 15 years, and is now being blamed by both national and international media for the desperate economic mess the country is in.

But blaming the Rajapaksas alone is too simple. Certainly, the aggressive majoritarianism that they unleashed, along with the alleged corruption and major economic policy disasters of recent years (such as drastic tax cuts and bans on fertiliser imports), were crucial elements of the economic debacle. But this is only part of the story. The deeper and underlying causes of the crisis in Sri Lanka are barely mentioned by most mainstream commentators, perhaps because they reveal uncomfortable truths about the way the global economy works.

This is not a crisis created by a few recent external and internal factors, it has been decades in the making. Ever since its “open economic policy” was adopted in the late 1970s, Sri Lanka has been Asia’s poster boy for neoliberal reform, much like Chile in Latin America. The strategy was the now-familiar one of making exports the basis for economic growth, supported by foreign capital inflows. This led to a significant increase in foreign currency debt, something the IMF and the Davos crowd actively encouraged.

In the period after the 2008 global financial crisis, as low interest rates in advanced economies led to the availability of cheap credit, the Sri Lankan government relied on international sovereign bonds to finance its own spending. Between 2012 and 2020, the debt to GDP ratio doubled to around 80%, with a growing share of this in bonds. The payments due on these debts kept rising in relation to what Sri Lanka could earn from exports and the money sent back home by Sri Lankans working abroad. The disruptions caused by the pandemic and the war in Ukraine made matters much worse, by causing export earnings to fall and sharply increasing the price of essential imports including food and fuel. Foreign exchange reserves plummeted – but the government had to keep paying interest even when it could not import essential fuel.

Looked at in this light, it is clear that Sri Lanka is not alone; if anything, it’s just a harbinger of a coming storm of debt distress in what economists call the “emerging markets”. The past period of incredibly low interest rates in the advanced economies meant that more funds flowed to “emerging” and “frontier” markets from the richer world. While this found cheerleaders in the international financial institutions (IFIs), it was always a problematic process. This is because, unlike in places such as the EU and US, capital leaves low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) at the first sign of any problem.

And these countries were much more battered economically by the pandemic. Advanced economies were able to provide massive countercyclical measures – think of the UK’s furlough programme – because financial markets effectively allowed and even encouraged them to do so. By contrast, LMICs were prevented from increasing fiscal spending by much – because of those same financial markets, which threatened the possibility of credit downgrades and capital flight as government deficits grew larger. Plus they faced significant declines in export and tourism revenues and tighter balance of payments constraints. As a result, their economic recovery has been much more muted and economic conditions remain mostly dire.

The half-hearted attempts at debt relief, such as the moratorium on debt servicing in the first part of the pandemic, only postponed the problem. There has been no meaningful debt restructuring at all. The IMF bewails the situation and does almost nothing, and both it and World Bank add to the problem through their own rigid insistence on repayments and the appalling system of surcharges imposed by the IMF. The G7 and “international community” have been missing in action, which is deeply irresponsible given the scale of the problem and their role in creating it.

The sad truth is that “investor sentiment” moves against poorer economies regardless of the real economic conditions in specific countries. Private credit rating agencies amplify the problem. This means that contagion is all too likely, and it will affect not just economies that are already experiencing difficulties, but a much wider range of LMICs that will face real difficulties in servicing their debts. Lebanon, Suriname and Zambia are already in formal default; Belarus is on the brink; and Egypt, Ghana and Tunisia are in severe debt distress.

Many countries with lower per-capita income and significant absolute poverty are facing stagflation. Billions of people are increasingly unable to afford a basic nutritious diet, and cannot meet basic health expenses. Material insecurity and social tensions are inevitable.

The situation can still be resolved, but it requires urgent action, especially on the part of the IFIs and G7. Speedy and systematic debt resolution actions to bring in private creditors and other creditors, such as China, are needed, as is IFIs doing their own bit to provide debt relief and ending punitive measures such as surcharges. In addition, policies to limit speculation in commodity markets and profiteering by big food and fuel companies must be put in place. Finally, the recycling of special drawing rights (SDRs) – essentially “IMF coupons” – by countries that will not use them to countries that desperately need them is vital, as is another release of SDRs equating to about $650bn to provide immediate relief.

Without these minimal measures, the post-Covid, post-Ukraine global economy is likely to be engulfed in a dystopia of debt defaults, increasing poverty and sociopolitical instability.

Tuesday, 15 September 2020

To lead Britain through a crisis, you have to be able to see beyond it: Gordon Brown abandons Neoliberal Economics

When the economy collapsed in 2008, I had to think ahead. I fear too little thought has been given to our recovery after Coronavirus writes Gordon Brown

‘Our young people now face the worst labour market for 50 years.’ Photograph: Hollie Adams/Getty Images

Our country’s Covid-19 crisis, together with the economic crisis the pandemic brought with it, is not over. In fact, it is entering a dangerous new phase.

With the UK economy collapsing by 25% in March and April – a fall twice as bad as those in Europe and the US and now only halfway back to pre-crisis level – a recovery plan is needed: closer to France’s £90bn, Germany’s £115bn and the US’s £1tn is required, not the £30bn announced by the chancellor in July.

Millions of people – not 200,000 as now – must be tested every day if the mass return to the workplace is not to result in a second wave of the disease.

And, if the end of the furlough scheme on 31 October is not to bring the highest number of redundancies in living memory, new job-protection measures – based on the Office for Budget Responsibility’s assessment that unemployment could reach 3m – will have to be implemented in the next few days.

Already I see the Conservative economic doves of the spring reverting to type, emerging as the grasping fiscal hawks of autumn, unable to see that every economic orthodoxy has been turned on its head.

Having led the country through one big crisis after 2008 – I had to learn quickly, and learn from my own mistakes – I can feel some sympathy for Boris Johnson, even though mea culpa is the one Latin phrase that will never cross his lips. But I found back then that it was not enough just to do day-to-day crisis management, or even to be one step ahead of events; the real challenge is to anticipate the next problem but one.

More than that, to solve each problem I had to get to the root of it, often by overriding conventional thinking, and following that up with a relentless determination to mobilise all the weapons at one’s disposal. In 2008 the banks were running capitalism without capital, so we nationalised strategically important financial institutions.

Now, in 2020 and still in the absence of a vaccine or a cure, we should have been clear from the outset that regular mass testing was – and still is – the effective way to detect the spread of the disease and then to respond with prompt local public health interventions.

But I fear that those responsible – having misspent millions on contracts for serially ineffective initiatives – have given too little thought to what also matters in the days ahead: engineering the long-term recovery.

Investing now – to save good companies and prevent the destruction of capacity and the loss of key jobs and skills for good – means following Germany and France by maintaining furlough payments in key sectors, preferably with a wage subsidy for part-time work, and with the backstop offer of retraining during absence from the workplace.

And, where workers have to stay at home to avoid the spread of infections during the inevitable increase of pandemic-related local lockdowns, the support available to them has to feed their families, which today’s miserly £90 a week does not.

Our young people now face the worst labour market for 50 years – yet today’s youth employment programme will assist only 350,000, and only for six months, when there are 3.5 million under-25s who are not in full-time education. So to guarantee a job, training or education requires a far more rapid expansion of new apprenticeship, college and university places, along with the re-introduction of the more generous future jobs programme that we had in 2009.

Tory austerity was never a good idea and is now an admitted failure. But it is frankly an economic absurdity when government borrowing costs are so small – 10-year gilt yields are around one-20th of those of 2008 – and unmet needs so extensive.

Indeed inflation – once seen as the justification for austerity economics – is so low in the US today that the Federal Reserve has deemed that maximising employment will now be its main priority. Again, the UK is behind the curve. In 1998, serving as chancellor, I was responsible for the Bank of England Act, which required the Bank to pursue high levels of employment. Now I am the first to say that the Bank needs a more demanding constitution, one that imposes a dual mandate: to take unemployment as seriously as inflation. This should be matched by an operational target stating that interest rates will not rise or stimulus end until unemployment falls to pre-crisis levels.

The current crisis is of course global as much as it is domestic. From 2008 to 2010, I spent much of my time persuading my fellow leaders to act as one, and to agree a synchronised stimulus alongside aid for developing countries. But I am shocked that now – with the world’s economies simultaneously damaged by the pandemic and an economic shock far worse than back then – the world’s leaders have done so little work together in response.

In short, all countries should be agreeing to call time on 50 years of neoliberal economics. They should break not only with their exclusive focus on controlling inflation, but with the pursuit of deregulation, liberalisation and privatisation at the expense of fairness, employment and sustainability. That project, once called the Washington consensus, is out of favour even in Washington. A new paradigm would give priority to fair trade, not just free trade; better control of the management of destabilising capital flows to replace the current free-for-all; a competition regime that can robustly address monopolistic behaviour from rent-seeking digital platforms; an industrial policy that would include generous support for science and innovation – with all that wrapped in a commitment to action on climate change and action on unacceptable levels of inequality.

Could it happen here? I believe so. While the government may feel able to steamroller its policies through the House of Commons thanks to an 80-seat majority, our multinational and increasingly regionally diverse country can no longer be straitjacketed, as now, by a remote and failing centralised state.

In contrast to the tiny and fallible cabal in No 10, democracy is rising again elsewhere: no longer just MPs and local councillors, but directly elected metro mayors and elected decision-making bodies in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. And, as with the outrage against the government’s breach of international law, a rebellion of the regions and nations could force the prime minister to listen.

A challenge no doubt, especially with this prime minister. But he is already worried about the fragility of his recently acquired strength in the north of England; and as a unionist, he knows he must also take heed of voices in Scotland and Wales, where his popularity is waning fast. Politically – and despite his formidable record in the genre – he knows he cannot afford a U-turn on the union.

A strong alliance encompassing trades unions and businesses too can thus not only press for a recovery plan but also revive the spirit of cooperation and unity across our country – and, through a newfound solidarity, give the British people what we need most: hope.

Our country’s Covid-19 crisis, together with the economic crisis the pandemic brought with it, is not over. In fact, it is entering a dangerous new phase.

With the UK economy collapsing by 25% in March and April – a fall twice as bad as those in Europe and the US and now only halfway back to pre-crisis level – a recovery plan is needed: closer to France’s £90bn, Germany’s £115bn and the US’s £1tn is required, not the £30bn announced by the chancellor in July.

Millions of people – not 200,000 as now – must be tested every day if the mass return to the workplace is not to result in a second wave of the disease.

And, if the end of the furlough scheme on 31 October is not to bring the highest number of redundancies in living memory, new job-protection measures – based on the Office for Budget Responsibility’s assessment that unemployment could reach 3m – will have to be implemented in the next few days.

Already I see the Conservative economic doves of the spring reverting to type, emerging as the grasping fiscal hawks of autumn, unable to see that every economic orthodoxy has been turned on its head.

Having led the country through one big crisis after 2008 – I had to learn quickly, and learn from my own mistakes – I can feel some sympathy for Boris Johnson, even though mea culpa is the one Latin phrase that will never cross his lips. But I found back then that it was not enough just to do day-to-day crisis management, or even to be one step ahead of events; the real challenge is to anticipate the next problem but one.

More than that, to solve each problem I had to get to the root of it, often by overriding conventional thinking, and following that up with a relentless determination to mobilise all the weapons at one’s disposal. In 2008 the banks were running capitalism without capital, so we nationalised strategically important financial institutions.

Now, in 2020 and still in the absence of a vaccine or a cure, we should have been clear from the outset that regular mass testing was – and still is – the effective way to detect the spread of the disease and then to respond with prompt local public health interventions.

But I fear that those responsible – having misspent millions on contracts for serially ineffective initiatives – have given too little thought to what also matters in the days ahead: engineering the long-term recovery.

Investing now – to save good companies and prevent the destruction of capacity and the loss of key jobs and skills for good – means following Germany and France by maintaining furlough payments in key sectors, preferably with a wage subsidy for part-time work, and with the backstop offer of retraining during absence from the workplace.

And, where workers have to stay at home to avoid the spread of infections during the inevitable increase of pandemic-related local lockdowns, the support available to them has to feed their families, which today’s miserly £90 a week does not.

Our young people now face the worst labour market for 50 years – yet today’s youth employment programme will assist only 350,000, and only for six months, when there are 3.5 million under-25s who are not in full-time education. So to guarantee a job, training or education requires a far more rapid expansion of new apprenticeship, college and university places, along with the re-introduction of the more generous future jobs programme that we had in 2009.

Tory austerity was never a good idea and is now an admitted failure. But it is frankly an economic absurdity when government borrowing costs are so small – 10-year gilt yields are around one-20th of those of 2008 – and unmet needs so extensive.

Indeed inflation – once seen as the justification for austerity economics – is so low in the US today that the Federal Reserve has deemed that maximising employment will now be its main priority. Again, the UK is behind the curve. In 1998, serving as chancellor, I was responsible for the Bank of England Act, which required the Bank to pursue high levels of employment. Now I am the first to say that the Bank needs a more demanding constitution, one that imposes a dual mandate: to take unemployment as seriously as inflation. This should be matched by an operational target stating that interest rates will not rise or stimulus end until unemployment falls to pre-crisis levels.

The current crisis is of course global as much as it is domestic. From 2008 to 2010, I spent much of my time persuading my fellow leaders to act as one, and to agree a synchronised stimulus alongside aid for developing countries. But I am shocked that now – with the world’s economies simultaneously damaged by the pandemic and an economic shock far worse than back then – the world’s leaders have done so little work together in response.

In short, all countries should be agreeing to call time on 50 years of neoliberal economics. They should break not only with their exclusive focus on controlling inflation, but with the pursuit of deregulation, liberalisation and privatisation at the expense of fairness, employment and sustainability. That project, once called the Washington consensus, is out of favour even in Washington. A new paradigm would give priority to fair trade, not just free trade; better control of the management of destabilising capital flows to replace the current free-for-all; a competition regime that can robustly address monopolistic behaviour from rent-seeking digital platforms; an industrial policy that would include generous support for science and innovation – with all that wrapped in a commitment to action on climate change and action on unacceptable levels of inequality.

Could it happen here? I believe so. While the government may feel able to steamroller its policies through the House of Commons thanks to an 80-seat majority, our multinational and increasingly regionally diverse country can no longer be straitjacketed, as now, by a remote and failing centralised state.

In contrast to the tiny and fallible cabal in No 10, democracy is rising again elsewhere: no longer just MPs and local councillors, but directly elected metro mayors and elected decision-making bodies in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. And, as with the outrage against the government’s breach of international law, a rebellion of the regions and nations could force the prime minister to listen.

A challenge no doubt, especially with this prime minister. But he is already worried about the fragility of his recently acquired strength in the north of England; and as a unionist, he knows he must also take heed of voices in Scotland and Wales, where his popularity is waning fast. Politically – and despite his formidable record in the genre – he knows he cannot afford a U-turn on the union.

A strong alliance encompassing trades unions and businesses too can thus not only press for a recovery plan but also revive the spirit of cooperation and unity across our country – and, through a newfound solidarity, give the British people what we need most: hope.

Friday, 3 July 2020

Inside China’s race to beat poverty

China may be currently unpopular with the rest of the world; but, like the Soviets before them, they claim to have lifted large numbers of people out of poverty writes Yuan Yang and Nian Liu in The FT

Two A3-sized cards hanging outside the door of Jike Shibu’s house in Atule’er, a village perched on a cliff in the mountains of south-west China, were enough to determine his family’s fate. One was white and divided into four sections: “Having a good house; living a good life; cultivating good habits; creating a good atmosphere.” Each section was scored out of 100, with Jike’s family gaining just 65 points on the issue of housing.

Next to the white card was a red one, granting them the title of “poverty-stricken household with a card and record”. On it, an official’s handwritten recommendations for how the family could improve their lot. Their “main cause of poverty” was diagnosed as “bad transport infrastructure and lack of money”. Recommended measures included growing higher-profit crops, such as Sichuanese peppercorn, and “changing their customs”.

By themselves, the cards are not much use to the villagers: very few of those born before the 2000s read Chinese characters fluently. But the writing on them has changed their futures — in Jike’s case, resettling his family in a purpose-built, bustling compound in the nearby market town of Zhaojue.

Zhaojue is a place in a hurry. The government has set a deadline of the end of this month to end extreme poverty in the surrounding county of Liangshan, one of the most deprived in China. “Win the tough battle to end poverty,” proclaims the central hotel on a red electronic marquee — along with the number of days to the deadline. On the narrow streets outside, farmers rush around with wicker baskets full of produce, and vendors sell shoes and clothes piled high on plastic sheets.

The roots of this frantic activity go back to 2013, when leader Xi Jinping set a deadline for all of China’s rural counties to eradicate extreme poverty by the end of 2020. In the four decades since market reform began, China has already made huge advances in this area, winning praise from the UN, World Bank and figures from Bill Gates to Bernie Sanders, for raising 850 million people out of extreme poverty.

For both Xi and the Chinese Communist party, poverty-alleviation goals are more than a policy target. They are also a major source of legitimacy, both inside China and globally. “In my opinion, western politicians act for the next election. [By contrast] China has a ruling party that wants to achieve big goals,” says Hu Angang, a government adviser and head of China Studies at Tsinghua university. “In the history of human development, China achieving this is, if not unique, then at least something worthy of admiration.”

In the five years of Xi’s first term, an average of 13 million people were lifted out of poverty each year, according to the government. Some 775,000 officials were sent to villages to lead poverty alleviation and the government fund for this purpose increased by more than 20 per cent annually since 2013. State media said in March that central coffers had already handed out Rmb139.6bn (£15.8bn) of an estimated Rmb146bn this year. But the Covid-19 epidemic has led to an economic downturn, with the country’s GDP for the first quarter shrinking for the first time in four decades. Areas that were already deprived have been some of the hardest hit.

By the end of 2019, there were still 5.5 million individuals in extreme rural poverty around China. Xi’s goal is to bring this figure to zero in time for the centenary of the Communist party in July 2021. Coinciding with this would allow him to declare that China is prosperous and deserves to be a world leader, says Gao Qin, an expert on China’s social welfare at Columbia University. “The government is determined to achieve this goal,” says Gao. “Since March, official publications have reaffirmed that it must happen by the end of the year.”

In a bid to do this, the fronts for Xi’s “tough battle” on poverty are shifting. “Some villages are in extreme poverty that is difficult to alleviate, because of natural conditions and of the lack of transport infrastructure. In these places, very few villagers can become migrant workers and they rely on subsistence agriculture,” says Wang Xiangyang, assistant professor of public affairs at Southwest Jiaotong University. These include remote mountain communities such as the one in which Jike lives.

Atule’er — or Cliff Village as it is now widely known in China — sits atop a 1,400m mountain. Like many of the Yi ethnic minority areas of Liangshan, it is infrequently visited by tourists and difficult to reach, and may well have stayed that way had it not come to national prominence in 2016. That year, a local media feature showed children clinging to an old, crumbling vine ladder on their two-hour descent to the nearest school. Soon, more journalists arrived, and the local government pledged a new 800m steel ladder.

“Liangshan became the forefront of poverty alleviation — a lab within the country,” says Jan Karlach, research fellow at the Czech Academy of Sciences, whose research has focused on Liangshan and the Nuosu-Yi for the past 10 years. In 2017, at the annual meeting of China’s parliament, Xi dropped by the Sichuan province delegation to ask about progress alleviating poverty among the Yi people. “When I saw a report about the Liangshan cliff village on television . . . I felt anxious,” he said.

Over the past few months, the local government has resettled 84 households, or half the village, in Zhaojue, giving them apartments at the heavily subsidised price of Rmb10,000 (£1,130) per apartment. The “resettlement homes” are located a two-hour drive away from the base of Atule’er’s mountain, with a red banner across the entrance welcoming new residents.

The villagers allocated these flats are happy to have them. On the mountaintop, their earthen houses are exposed to the rain, as well as fatal rock slides. There, the only industry is subsistence farming. There is no medical care or formal education.

While some Yi academics question the changing of local (non-Han Chinese) customs for those moved from Cliff Village, the Communist party’s efforts have been largely welcomed. “Even my traditionalist friend — who said he couldn’t live in a house without a Yi fireplace — ditched the idea within a year,” says Karlach. His friend now lives in a town apartment with a picture of Xi on the wall: a poster handed out by local officials to remind poor households who to thank.

But others are not yet sure how to adapt to life in the town, where they will have to transform their mountain-dwelling culture to fit the 100 sq m apartments. “My mother isn’t keen to come down from the mountaintop,” says the 24-year-old Jike. “Elderly people don’t like the town, they say there’s no land and nothing to eat there. I say, ‘What others eat, you’ll eat.’ The elderly can’t stay up there on their own.”

Recently, Jike has been carrying heavy loads of bedding and clothes on his trips down the mountain, getting ready for his move. He has also acquired a following on social media. Hopping between slippery footholds, his giant plastic pack on his back, he holds his smartphone out on a selfie stick and chats cheerfully to fans on Douyin, China’s domestic version of TikTok. Jike can earn Rmb3,000 per month from live-streaming: a fortune compared with the Rmb700 average for rural locals.

He has agreed to take us up to his village in part because he believes the residents who remain there need a better platform to air their views. In some regions, China’s strategy of development through urbanisation has led to forced demolitions, and farmers stripped of the land their families had tended for generations. But Cliff Village faces the opposite problem: there are many more people who want to move than the government has relocated.

Over the two days that we spend there, more people approach us, wanting to show us the insides of their houses and tell us how the local government has overlooked them. In Zhaojue, the threshold for being extremely poor is living on less than Rmb4,200 per year (£475) and, in Cliff Village, such officially “poverty-stricken” households receive a basic income guarantee, the right to buy cut-price new apartments — and even 30 chickens.

But there are also those unlucky enough to be officially logged as poor, either through neglect, miscalculation or mere bureaucracy. They do not receive the same benefits, although they are entitled to some payments, such as the minimum livelihood guarantee. They also do not count towards the government’s poverty-eradication target. In some cases, the government has solved meeting its poverty targets administratively: certain areas have stopped logging residents as “impoverished” since the start of the year. “It’s all been counted, the system no longer takes new impoverished households,” says Azi Aniu, a local county-level party secretary. (He later vacillated on this point, telling us that they were able to log new impoverished households but chose not to.)

While the rapid rate of alleviation is real, the true level of poverty may be impossible to gauge in a system not designed to admit mistakes. According to official policy, if the minimum-livelihood guarantee was being implemented properly, such impoverished households would not exist. The current database will be overhauled for the next step of China’s development plan, which will move on to “precarious” or “borderline” households.

According to Li Shi, professor of economics at Beijing Normal University, surveys from 2014 suggested some 60 per cent of those who should qualify for “poverty-stricken” status based on their low incomes did not get the designation. In the years that followed, “some adjustments were made, and there should be some improvement,” Li wrote.

But many of those still in Atule’er feel left behind. “You’re not going to write one of those ‘Goodbye to Cliff Village’ articles, are you?” asks Jike Quri, a man who had waited all day at the top of the steel ladder for us to arrive. “There is no goodbye: half of us are still here.”

Within an hour of us checking in, local authorities arrived at our hotel door, indicating the sensitivities around this story. State media had come the week before to report on one of the most high-profile battlegrounds in China’s anti-poverty push, and had written stories about happy villagers moving into their flats.

In one local media spread, the family of Mou’se Xiongti, a 25-year-old man, were photographed in their new flat, the bed decked with blankets. When we visited Mou’se’s flat, it was empty except for the government-provided furniture: a set of cabinets, sofa, chairs, tables and bed. Many items were stamped with “People’s Government of Sichuan Provincial Committee of the Communist Party of China”.

The nervousness of local politicians is largely due to the fact that Cliff Village is now renowned for its role as part of a high-level target: Xi has personally embraced poverty alleviation, boosting his populist image as a “peasant emperor” with sympathies for ordinary Chinese people — a persona not dissimilar to that cultivated by Mao Zedong. State propaganda often depicts Xi chatting with farmers about the harvest, sitting cross-legged in village homes or laughing with pensioners. In his first five-year presidential term from 2012, he visited 180 poor regions across 20 provinces. He visited Liangshan in 2018.

The red and white cards that ultimately gave Jike Shibu’s family a flat are part of a policy which required creating a database of households and checking their progress. This campaign came with a boost in government funding for rural social welfare projects, a powerful committee to guide policy and the establishment of a national database of poor households. By the end of this year, that system must be cleared of households like Jike’s.

But the villagers still left in Atule’er say they have not received such targeted attention from the local officials, who, they allege, don’t bother to visit their mountaintop homes that often. (The local official Azi counters that he has trekked up the mountain so many times he has damaged his legs.) As a result, they complain there is no meaningful distinction between “poverty-stricken” households and others, and those in need of help are not getting it.

Some households face the problem of getting lumped together into one record. This happens when adults with their own children are still marked on the record of their parents, meaning they are only assigned one house. Often, officials reject their requests to register new households.

Others suffer Kafkaesque bureaucratic processes. Jizu Wuluo, a 37-year-old widow and mother to four children, two of whom she had to give up for adoption, is determined to give her youngest a good education and rents a flat near the school at the bottom of the cliff. Jizu ticks many of the boxes of an “impoverished” household: she lives in one of the fragile houses on Cliff Village, heads a single-earner family and also “suffers hardship for education”.

However, although she has tried to get “impoverished” status on several occasions, each time officials told her to wait. In October last year she and her two sons were finally each given a minimum livelihood guarantee of Rmb2,940 per year, part of the government’s package of anti-poverty measures that it uses when all else fails. About 43 million people receive it nationwide. In Zhaojue county, the maximum paid per rural recipient per year is Rmb4,200.

“I know Xi Jinping said to help those poor and suffering ordinary folk, but when it comes to grassroots officials like you, you only help those people who already have standing in society,” she says in a meeting with Azi, who listened patiently to a string of complaints.

After we left, Azi quickly followed up on Jizu’s case. The explanation for why she had not been prioritised for an apartment raised more questions than it answered. Jizu had been missed out of the first survey of impoverished households in 2013. Later, she was recorded as “an impoverished household without an official record”. Azi says they could not create an official “impoverished household” record for her after her husband died in 2018. Instead, they added more labels to her case. Azi couldn’t say when the list of impoverished households stopped being amended but, he says, Jizu will be moved into town by the end of the year.

“The relocation apartments are beautiful, they are better than other properties in town, so some villagers get a bit jealous,” says Azi. “I’m being very straightforward with you.”

Moving into town may be one step towards ensuring a secure livelihood, but the most important is finding work. Local officials encourage the younger generation to seek jobs in cities, particularly those along the industrialised south-east coast. For decades, rural-urban migration has been the standard way of improving livelihoods: some 236 million people in China are migrant workers, according to government statistics.

Of the locals we spoke to in their late teens and twenties, many had gone out to work for a few months at a time. Most did unskilled labour in construction and went in groups arranged by friends or relatives. Like migrants from around China, Liangshan’s workers live as second-class citizens when they arrive in major cities, where it is almost impossible to access healthcare or education for their children. During the coronavirus epidemic, these workers — who often had to continue delivering groceries and cleaning hospitals — were highly vulnerable.

The work that Liangshan locals can do is also limited by their education. Most of our interviewees were semi-literate at best, and some did not speak Mandarin. The internet is changing that. Social media, ecommerce and live-streaming have created greater opportunity for reading and writing outside of the world of formal education. Jike, who received just two years of schooling, says he learnt a lot about reading, writing and speaking Chinese from live-streaming. Every now and then, as viewers’ comments flash in real time across his screen, he addresses the commenter by saying, “Sister, I can’t read that.”

Education is another way of leaving the village. While some families prefer to let their children work, others are keen to send them to school. Mou’se Lazuo, the 17-year-old sister of Xiongti, hopes to break the trend in her village by going to university. She is the oldest girl in Cliff Village still at school; the older ones have gone to work or got married. She is one of 72 students in her class.

While she speaks Yi at home, Mou’se studies in Mandarin, with the exception of an hour and a half of Yi language classes per week. “I think it’s fine for Han culture to come here, so long as Han culture and Yi exist side by side,” she says. “We can’t leave parts of our traditional culture, like our legends and our language.”

The Yi didn’t come to China: China came to the Yi. Yi people have lived in the mountains of Liangshan for centuries, not far from Sichuan’s borders with Tibet and Myanmar. After teetering on the edge of the Chinese empire for over a millennium, Liangshan was brought under Communist rule in 1957 with the help of the People’s Liberation Army. The Yi were categorised as such by anthropologists sent by the Beijing-based national government in the 1950s, who determined the roster of 55 officially recognised ethnic minorities.

“It’s a civilising project,” says Karlach, the researcher who has lived in Liangshan, describing the government’s attitude towards poverty alleviation with ethnic minorities. “In Liangshan, in many places, they’re not offered to indigenise or develop their own modernity: they are given the modernity from the outside. They want to be Chinese and are proud to be Chinese, but also want to be Yi.”

For the government, teaching the Mandarin language and Han customs not only makes ethnic minorities easier to govern, but also helps them fit into a Han-dominated economy. Also, rapid urbanisation has changed all traditional cultures in China, subsuming them into the monoculture of the city and of earning money.

In Zhaojue, most shops employ at least some locals, although the newer ones are largely run by Han Chinese migrants from richer parts of China. “Generally, local workers don’t stay for long,” says Mao Dongtian, an entrepreneur from the coastal city of Wenzhou. He has opened a local chain of cafés and karaoke bars. His staff earn between Rmb1,000 and Rmb3,000 — a decent amount for the area — but don’t like the discipline and loss of freedom that come with a full-time job, he says.

“Their ways are more backwards than the Han people, and we are trying to teach them our ways,” continues Mao, describing how he encouraged his staff to seek medical help for ailments rather than rely on folk treatments. Such beliefs are typical of the majority ethnic group’s attitudes towards China’s minorities. Though some of these attitudes are rooted in stereotypes, others reflect a way of life shaped by subsistence agriculture.

When I ask Jike what he will most miss about Cliff Village, he says “the view”. He plans to make the trip up now and again to enjoy it. After sunset, there are innumerable stars and the night is black and quiet. Zhaojue, on the other hand, is lit with streetlamps and has the bustle of people and cars.

After June 30, the government will move on to the next stage of China’s development plan: “the strategy to revitalise villages”. Although China’s development plans have focused on the rural poor, the urban poor are of increasing concern. They are more likely to slip between the bureaucratic cracks, as they are often not registered in the places where they live and work. Cities are loath to accept such migrants: two years ago, Beijing “cleaned out” residents referred to by politicians as the “low-end population”. Some economists estimate that about 50 million migrant workers became unemployed at the start of the epidemic.

This month, Premier Li Keqiang sparked a public outcry over Xi’s claims of success on poverty alleviation, after announcing that the bottom two-fifths of the population made on average an income of less than Rmb1,000 a month. Those 600 million people constitute a significant proportion of city dwellers as well as the rural poor.

“Somehow or other, this [poverty] target will be declared to have been achieved and will form a part of the big celebrations next year. And then the goalposts will shift, I suspect towards issues of equality and equity,” said Kerry Brown, a scholar of Chinese politics at King’s College London. “That’s really where the key battleground will be, because inequality in China is a serious problem and it’s not getting better.”

Two A3-sized cards hanging outside the door of Jike Shibu’s house in Atule’er, a village perched on a cliff in the mountains of south-west China, were enough to determine his family’s fate. One was white and divided into four sections: “Having a good house; living a good life; cultivating good habits; creating a good atmosphere.” Each section was scored out of 100, with Jike’s family gaining just 65 points on the issue of housing.

Next to the white card was a red one, granting them the title of “poverty-stricken household with a card and record”. On it, an official’s handwritten recommendations for how the family could improve their lot. Their “main cause of poverty” was diagnosed as “bad transport infrastructure and lack of money”. Recommended measures included growing higher-profit crops, such as Sichuanese peppercorn, and “changing their customs”.

By themselves, the cards are not much use to the villagers: very few of those born before the 2000s read Chinese characters fluently. But the writing on them has changed their futures — in Jike’s case, resettling his family in a purpose-built, bustling compound in the nearby market town of Zhaojue.

Zhaojue is a place in a hurry. The government has set a deadline of the end of this month to end extreme poverty in the surrounding county of Liangshan, one of the most deprived in China. “Win the tough battle to end poverty,” proclaims the central hotel on a red electronic marquee — along with the number of days to the deadline. On the narrow streets outside, farmers rush around with wicker baskets full of produce, and vendors sell shoes and clothes piled high on plastic sheets.

The roots of this frantic activity go back to 2013, when leader Xi Jinping set a deadline for all of China’s rural counties to eradicate extreme poverty by the end of 2020. In the four decades since market reform began, China has already made huge advances in this area, winning praise from the UN, World Bank and figures from Bill Gates to Bernie Sanders, for raising 850 million people out of extreme poverty.

For both Xi and the Chinese Communist party, poverty-alleviation goals are more than a policy target. They are also a major source of legitimacy, both inside China and globally. “In my opinion, western politicians act for the next election. [By contrast] China has a ruling party that wants to achieve big goals,” says Hu Angang, a government adviser and head of China Studies at Tsinghua university. “In the history of human development, China achieving this is, if not unique, then at least something worthy of admiration.”

In the five years of Xi’s first term, an average of 13 million people were lifted out of poverty each year, according to the government. Some 775,000 officials were sent to villages to lead poverty alleviation and the government fund for this purpose increased by more than 20 per cent annually since 2013. State media said in March that central coffers had already handed out Rmb139.6bn (£15.8bn) of an estimated Rmb146bn this year. But the Covid-19 epidemic has led to an economic downturn, with the country’s GDP for the first quarter shrinking for the first time in four decades. Areas that were already deprived have been some of the hardest hit.

By the end of 2019, there were still 5.5 million individuals in extreme rural poverty around China. Xi’s goal is to bring this figure to zero in time for the centenary of the Communist party in July 2021. Coinciding with this would allow him to declare that China is prosperous and deserves to be a world leader, says Gao Qin, an expert on China’s social welfare at Columbia University. “The government is determined to achieve this goal,” says Gao. “Since March, official publications have reaffirmed that it must happen by the end of the year.”

In a bid to do this, the fronts for Xi’s “tough battle” on poverty are shifting. “Some villages are in extreme poverty that is difficult to alleviate, because of natural conditions and of the lack of transport infrastructure. In these places, very few villagers can become migrant workers and they rely on subsistence agriculture,” says Wang Xiangyang, assistant professor of public affairs at Southwest Jiaotong University. These include remote mountain communities such as the one in which Jike lives.

Atule’er — or Cliff Village as it is now widely known in China — sits atop a 1,400m mountain. Like many of the Yi ethnic minority areas of Liangshan, it is infrequently visited by tourists and difficult to reach, and may well have stayed that way had it not come to national prominence in 2016. That year, a local media feature showed children clinging to an old, crumbling vine ladder on their two-hour descent to the nearest school. Soon, more journalists arrived, and the local government pledged a new 800m steel ladder.

“Liangshan became the forefront of poverty alleviation — a lab within the country,” says Jan Karlach, research fellow at the Czech Academy of Sciences, whose research has focused on Liangshan and the Nuosu-Yi for the past 10 years. In 2017, at the annual meeting of China’s parliament, Xi dropped by the Sichuan province delegation to ask about progress alleviating poverty among the Yi people. “When I saw a report about the Liangshan cliff village on television . . . I felt anxious,” he said.

Over the past few months, the local government has resettled 84 households, or half the village, in Zhaojue, giving them apartments at the heavily subsidised price of Rmb10,000 (£1,130) per apartment. The “resettlement homes” are located a two-hour drive away from the base of Atule’er’s mountain, with a red banner across the entrance welcoming new residents.

The villagers allocated these flats are happy to have them. On the mountaintop, their earthen houses are exposed to the rain, as well as fatal rock slides. There, the only industry is subsistence farming. There is no medical care or formal education.

While some Yi academics question the changing of local (non-Han Chinese) customs for those moved from Cliff Village, the Communist party’s efforts have been largely welcomed. “Even my traditionalist friend — who said he couldn’t live in a house without a Yi fireplace — ditched the idea within a year,” says Karlach. His friend now lives in a town apartment with a picture of Xi on the wall: a poster handed out by local officials to remind poor households who to thank.

But others are not yet sure how to adapt to life in the town, where they will have to transform their mountain-dwelling culture to fit the 100 sq m apartments. “My mother isn’t keen to come down from the mountaintop,” says the 24-year-old Jike. “Elderly people don’t like the town, they say there’s no land and nothing to eat there. I say, ‘What others eat, you’ll eat.’ The elderly can’t stay up there on their own.”

Recently, Jike has been carrying heavy loads of bedding and clothes on his trips down the mountain, getting ready for his move. He has also acquired a following on social media. Hopping between slippery footholds, his giant plastic pack on his back, he holds his smartphone out on a selfie stick and chats cheerfully to fans on Douyin, China’s domestic version of TikTok. Jike can earn Rmb3,000 per month from live-streaming: a fortune compared with the Rmb700 average for rural locals.

He has agreed to take us up to his village in part because he believes the residents who remain there need a better platform to air their views. In some regions, China’s strategy of development through urbanisation has led to forced demolitions, and farmers stripped of the land their families had tended for generations. But Cliff Village faces the opposite problem: there are many more people who want to move than the government has relocated.

Over the two days that we spend there, more people approach us, wanting to show us the insides of their houses and tell us how the local government has overlooked them. In Zhaojue, the threshold for being extremely poor is living on less than Rmb4,200 per year (£475) and, in Cliff Village, such officially “poverty-stricken” households receive a basic income guarantee, the right to buy cut-price new apartments — and even 30 chickens.

But there are also those unlucky enough to be officially logged as poor, either through neglect, miscalculation or mere bureaucracy. They do not receive the same benefits, although they are entitled to some payments, such as the minimum livelihood guarantee. They also do not count towards the government’s poverty-eradication target. In some cases, the government has solved meeting its poverty targets administratively: certain areas have stopped logging residents as “impoverished” since the start of the year. “It’s all been counted, the system no longer takes new impoverished households,” says Azi Aniu, a local county-level party secretary. (He later vacillated on this point, telling us that they were able to log new impoverished households but chose not to.)

While the rapid rate of alleviation is real, the true level of poverty may be impossible to gauge in a system not designed to admit mistakes. According to official policy, if the minimum-livelihood guarantee was being implemented properly, such impoverished households would not exist. The current database will be overhauled for the next step of China’s development plan, which will move on to “precarious” or “borderline” households.

According to Li Shi, professor of economics at Beijing Normal University, surveys from 2014 suggested some 60 per cent of those who should qualify for “poverty-stricken” status based on their low incomes did not get the designation. In the years that followed, “some adjustments were made, and there should be some improvement,” Li wrote.

But many of those still in Atule’er feel left behind. “You’re not going to write one of those ‘Goodbye to Cliff Village’ articles, are you?” asks Jike Quri, a man who had waited all day at the top of the steel ladder for us to arrive. “There is no goodbye: half of us are still here.”

Within an hour of us checking in, local authorities arrived at our hotel door, indicating the sensitivities around this story. State media had come the week before to report on one of the most high-profile battlegrounds in China’s anti-poverty push, and had written stories about happy villagers moving into their flats.

In one local media spread, the family of Mou’se Xiongti, a 25-year-old man, were photographed in their new flat, the bed decked with blankets. When we visited Mou’se’s flat, it was empty except for the government-provided furniture: a set of cabinets, sofa, chairs, tables and bed. Many items were stamped with “People’s Government of Sichuan Provincial Committee of the Communist Party of China”.

The nervousness of local politicians is largely due to the fact that Cliff Village is now renowned for its role as part of a high-level target: Xi has personally embraced poverty alleviation, boosting his populist image as a “peasant emperor” with sympathies for ordinary Chinese people — a persona not dissimilar to that cultivated by Mao Zedong. State propaganda often depicts Xi chatting with farmers about the harvest, sitting cross-legged in village homes or laughing with pensioners. In his first five-year presidential term from 2012, he visited 180 poor regions across 20 provinces. He visited Liangshan in 2018.

The red and white cards that ultimately gave Jike Shibu’s family a flat are part of a policy which required creating a database of households and checking their progress. This campaign came with a boost in government funding for rural social welfare projects, a powerful committee to guide policy and the establishment of a national database of poor households. By the end of this year, that system must be cleared of households like Jike’s.

But the villagers still left in Atule’er say they have not received such targeted attention from the local officials, who, they allege, don’t bother to visit their mountaintop homes that often. (The local official Azi counters that he has trekked up the mountain so many times he has damaged his legs.) As a result, they complain there is no meaningful distinction between “poverty-stricken” households and others, and those in need of help are not getting it.

Some households face the problem of getting lumped together into one record. This happens when adults with their own children are still marked on the record of their parents, meaning they are only assigned one house. Often, officials reject their requests to register new households.

Others suffer Kafkaesque bureaucratic processes. Jizu Wuluo, a 37-year-old widow and mother to four children, two of whom she had to give up for adoption, is determined to give her youngest a good education and rents a flat near the school at the bottom of the cliff. Jizu ticks many of the boxes of an “impoverished” household: she lives in one of the fragile houses on Cliff Village, heads a single-earner family and also “suffers hardship for education”.

However, although she has tried to get “impoverished” status on several occasions, each time officials told her to wait. In October last year she and her two sons were finally each given a minimum livelihood guarantee of Rmb2,940 per year, part of the government’s package of anti-poverty measures that it uses when all else fails. About 43 million people receive it nationwide. In Zhaojue county, the maximum paid per rural recipient per year is Rmb4,200.

“I know Xi Jinping said to help those poor and suffering ordinary folk, but when it comes to grassroots officials like you, you only help those people who already have standing in society,” she says in a meeting with Azi, who listened patiently to a string of complaints.

After we left, Azi quickly followed up on Jizu’s case. The explanation for why she had not been prioritised for an apartment raised more questions than it answered. Jizu had been missed out of the first survey of impoverished households in 2013. Later, she was recorded as “an impoverished household without an official record”. Azi says they could not create an official “impoverished household” record for her after her husband died in 2018. Instead, they added more labels to her case. Azi couldn’t say when the list of impoverished households stopped being amended but, he says, Jizu will be moved into town by the end of the year.

“The relocation apartments are beautiful, they are better than other properties in town, so some villagers get a bit jealous,” says Azi. “I’m being very straightforward with you.”

Moving into town may be one step towards ensuring a secure livelihood, but the most important is finding work. Local officials encourage the younger generation to seek jobs in cities, particularly those along the industrialised south-east coast. For decades, rural-urban migration has been the standard way of improving livelihoods: some 236 million people in China are migrant workers, according to government statistics.

Of the locals we spoke to in their late teens and twenties, many had gone out to work for a few months at a time. Most did unskilled labour in construction and went in groups arranged by friends or relatives. Like migrants from around China, Liangshan’s workers live as second-class citizens when they arrive in major cities, where it is almost impossible to access healthcare or education for their children. During the coronavirus epidemic, these workers — who often had to continue delivering groceries and cleaning hospitals — were highly vulnerable.

The work that Liangshan locals can do is also limited by their education. Most of our interviewees were semi-literate at best, and some did not speak Mandarin. The internet is changing that. Social media, ecommerce and live-streaming have created greater opportunity for reading and writing outside of the world of formal education. Jike, who received just two years of schooling, says he learnt a lot about reading, writing and speaking Chinese from live-streaming. Every now and then, as viewers’ comments flash in real time across his screen, he addresses the commenter by saying, “Sister, I can’t read that.”

Education is another way of leaving the village. While some families prefer to let their children work, others are keen to send them to school. Mou’se Lazuo, the 17-year-old sister of Xiongti, hopes to break the trend in her village by going to university. She is the oldest girl in Cliff Village still at school; the older ones have gone to work or got married. She is one of 72 students in her class.

While she speaks Yi at home, Mou’se studies in Mandarin, with the exception of an hour and a half of Yi language classes per week. “I think it’s fine for Han culture to come here, so long as Han culture and Yi exist side by side,” she says. “We can’t leave parts of our traditional culture, like our legends and our language.”

The Yi didn’t come to China: China came to the Yi. Yi people have lived in the mountains of Liangshan for centuries, not far from Sichuan’s borders with Tibet and Myanmar. After teetering on the edge of the Chinese empire for over a millennium, Liangshan was brought under Communist rule in 1957 with the help of the People’s Liberation Army. The Yi were categorised as such by anthropologists sent by the Beijing-based national government in the 1950s, who determined the roster of 55 officially recognised ethnic minorities.