Fifty years on, the 1973 coup in Chile still haunts politics there and far beyond. As we approach its anniversary, on 11 September, the violent overthrow of the elected socialist government of Salvador Allende and its replacement by the brutal dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet are already being marked in Britain, through a period of remembrance scheduled to include dozens of separate exhibitions and events. Among these will be a march in Sheffield, archival displays in Edinburgh, a concert in Swansea, and a conference and picket of the Chilean embassy in London.

Few past events in faraway countries receive this level of attention. Military takeovers were not unusual in South America during the cold war. And Chile has been a relatively stable democracy since the Pinochet dictatorship ended, 33 years ago. So why does the 1973 coup still resonate?

In the UK, one answer is that roughly 2,500 Chilean refugees fled here after the coup, despite an unwelcoming Conservative government. “It is intended to keep the number of refugees to a very small number and, if our criteria are not fully met, we may accept none of them,” said a Foreign Office memo not released until three decades afterwards.

The Chileans came regardless, partly because leftwing activists, trade unionists and politicians including Tony Benn and Jeremy Corbyn created a solidarity movement – of a scale and duration harder to imagine in our more politically impatient times – which helped the refugees build new lives, and campaigned with them for years against the Pinochet regime. Some of these exiles settled in Britain permanently; veterans of the solidarity movement are involved in this year’s remembrance events, as they have been in earlier anniversaries. The left’s reverence for old struggles can sometimes distract it or weigh it down, but it is also a source of emotional and cultural strength, and an acknowledgment that the past and present are often more linked than we realise.

Two weeks ago, it was revealed that an old army helicopter that stands in a wood in Sussex as part of a paintball course had previously been used by the Pinochet government, to transport dissidents and then throw them into the sea. The dictatorship was a pioneer of this and other methods of “disappearing” its enemies and perceived enemies, believing that lethal abductions would frighten the population into obedience more effectively than conventional state murders.

Not unconnectedly, the regime also pioneered the harsh free-market policies which transformed much of the world – and which are still supported by most Tories, many rightwing politicians in other countries, and many business interests. In Chile, the idea that a deregulated economy required a highly disciplined citizenry, to avoid the economic semi-anarchy spilling over into society, was exhaustively tested and refined, to the great interest of foreign politicians such as Margaret Thatcher.

Augusto Pinochet, left, and President Salvador Allende attend a ceremony naming Pinochet as commander in chief of the army, 23 August, 1973. Photograph: Enrique Aracena/AP

Another reason that the 1973 coup remains a powerful event is that it left unfinished business at the other end of the political spectrum. The Allende government was an argumentative and ambitious coalition which, almost uniquely, attempted to create a socialist country with plentiful consumer pleasures and modern technology, including a kind of early internet called Project Cybersyn, without Soviet-style repression. For a while, even the Daily Mail was impressed: “An astonishing experiment is taking place,” it reported on the first anniversary of his election. “If it survives, the implications will be immense for other countries.”

The coup happened partly because the government’s popularity, though never overwhelming, rose while it was in office. This rise convinced conservative interests that it would be reelected, and would then take the patchy reforms of its first term much further. For the same reasons, the Allende presidency remains tantalising for some on the left. An updated version of his combination of social liberalism, egalitarianism and mass political participation may still have the potential to transform the left’s prospects, as Corbyn’s successful campaigns in 2015, 2016 and 2017 suggested.

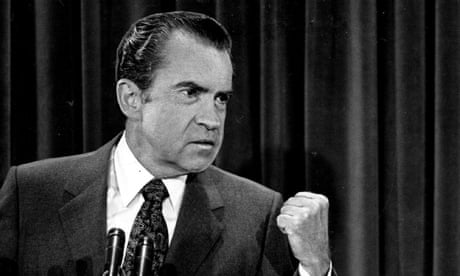

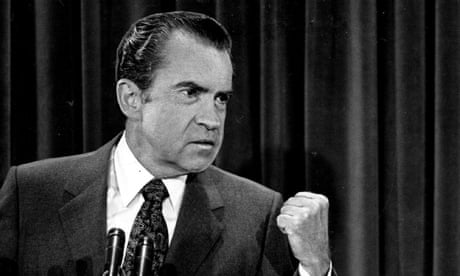

Files reveal Nixon role in plot to block Allende from Chilean presidency

There is one more, bleaker reason to reflect on the coup: for what it revealed about conservatism. When I wrote a book on Chile two decades ago, it was unsettling to learn about how the US Republicans undermined Allende, by covert CIA funding of his enemies, for instance, and how the Conservatives helped Pinochet, through arms sales and diplomatic support. But these moves seemed to be explained largely by cold-war strategies and free-market zealotry, which was fading in the early 21st century.

Yet from today’s perspective, with another Trump presidency threatening, far-right parties in power across Europe, and a Tory government with few, if any, inhibitions about criminalising dissent, the Chile coup looks prophetic. Nowadays the line between conservatism and authoritarianism is not so much blurred occasionally, in national emergencies, as nonexistent in many countries.

Some critics of conservatism would say that it’s naive to think such a line ever existed. In 1930s Europe, for instance, supposedly moderate and pro-democratic rightwing parties often facilitated the rise of fascism. Yet the postwar world, after fascism had been militarily defeated, was meant to be one where such toxic alliances against the left never happened again.

The 1973 coup ended that comfortable assumption. “It is not for us to pass judgment on Chile’s internal affairs,” said the Tory Foreign Office minister Julian Amery in the Commons, two months later, despite the coup having initiated killings and torture on a mass scale. When the coup is remembered, its victims should come first. But the response of conservatives around the world to the crushing of Chile’s democracy and civil liberties should never be forgotten.

Another reason that the 1973 coup remains a powerful event is that it left unfinished business at the other end of the political spectrum. The Allende government was an argumentative and ambitious coalition which, almost uniquely, attempted to create a socialist country with plentiful consumer pleasures and modern technology, including a kind of early internet called Project Cybersyn, without Soviet-style repression. For a while, even the Daily Mail was impressed: “An astonishing experiment is taking place,” it reported on the first anniversary of his election. “If it survives, the implications will be immense for other countries.”

The coup happened partly because the government’s popularity, though never overwhelming, rose while it was in office. This rise convinced conservative interests that it would be reelected, and would then take the patchy reforms of its first term much further. For the same reasons, the Allende presidency remains tantalising for some on the left. An updated version of his combination of social liberalism, egalitarianism and mass political participation may still have the potential to transform the left’s prospects, as Corbyn’s successful campaigns in 2015, 2016 and 2017 suggested.

Files reveal Nixon role in plot to block Allende from Chilean presidency

There is one more, bleaker reason to reflect on the coup: for what it revealed about conservatism. When I wrote a book on Chile two decades ago, it was unsettling to learn about how the US Republicans undermined Allende, by covert CIA funding of his enemies, for instance, and how the Conservatives helped Pinochet, through arms sales and diplomatic support. But these moves seemed to be explained largely by cold-war strategies and free-market zealotry, which was fading in the early 21st century.

Yet from today’s perspective, with another Trump presidency threatening, far-right parties in power across Europe, and a Tory government with few, if any, inhibitions about criminalising dissent, the Chile coup looks prophetic. Nowadays the line between conservatism and authoritarianism is not so much blurred occasionally, in national emergencies, as nonexistent in many countries.

Some critics of conservatism would say that it’s naive to think such a line ever existed. In 1930s Europe, for instance, supposedly moderate and pro-democratic rightwing parties often facilitated the rise of fascism. Yet the postwar world, after fascism had been militarily defeated, was meant to be one where such toxic alliances against the left never happened again.

The 1973 coup ended that comfortable assumption. “It is not for us to pass judgment on Chile’s internal affairs,” said the Tory Foreign Office minister Julian Amery in the Commons, two months later, despite the coup having initiated killings and torture on a mass scale. When the coup is remembered, its victims should come first. But the response of conservatives around the world to the crushing of Chile’s democracy and civil liberties should never be forgotten.